Abstract

The cellular heterogeneity seen in tumors, with subpopulations of cells capable of resisting different treatments, renders single-treatment regimens generally ineffective. Accordingly, there is a great need to increase the repertoire of drug treatments from which combinations may be selected to efficiently target sets of pathological processes, while suppressing the emergence of resistance mutations. In this regard, members of the TGF-β signaling pathway may furnish new, valuable therapeutic targets. In the present work, we developed in situ proximity ligation assays (isPLA) to monitor the state of the TGF-β signaling pathway. Moreover, we extended the range of suitable affinity reagents for this analysis by developing a set of in-vitro-derived human antibody fragments (single chain fragment variable, scFv) that bind SMAD2 (Mothers against decapentaplegic 2), 3, 4, and 7 using phage display. These four proteins are all intracellular mediators of TGF-β signaling. We also developed an scFv specific for SMAD3 phosphorylated in the linker domain 3 (p179 SMAD3). This phosphorylation has been shown to inactivate the tumor suppressor function of SMAD3. The single chain affinity reagents developed in the study were fused tocrystallizable antibody fragments (Fc-portions) and expressed as dimeric IgG-like molecules having Fc domains (Yumabs), and we show that they represent valuable reagents for isPLA.

Using these novel assays, we demonstrate that p179 SMAD3 forms a complex with SMAD4 at increased frequency during division and that pharmacological inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4)1 reduces the levels of p179SMAD3 in tumor cells. We further show that the p179SMAD3-SMAD4 complex is bound for degradation by the proteasome. Finally, we developed a chemical screening strategy for compounds that reduce the levels of p179SMAD3 in tumor cells with isPLA as a read-out, using the p179SMAD3 scFv SH544-IIC4. The screen identified two kinase inhibitors, known inhibitors of the insulin receptor, which decreased levels of p179SMAD3/SMAD4 complexes, thereby demonstrating the suitability of the recombinant affinity reagents applied in isPLA in screening for inhibitors of cell signaling.

The TGF-β signaling pathway regulates key cell fate decisions during embryonic development and in adult homeostasis. This pathway is deregulated in many pathological conditions, including cancer, autoimmunity, and fibrotic diseases. TGF-β functions as a tumor suppressor in early tumors, inhibiting progression through the cell cycle. In contrast, in later stages of cancer, TGF-β can have tumor-promoting effects. In particular, aberrant TGF-β signaling promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition, a critical event in metastatic spread during late-stage cancer progression (1, 2). Tumor cells can attenuate TGF-β signaling through mechanisms such as inactivating mutations (3), inhibitory phosphorylation of downstream signaling mediators, or increased expression of negative regulators (4). Recent evidence supports a role of TGF-β in tumor resistance to treatment (5).

TGF-β binds a heterotetrameric cell surface complex composed of type I and II serine/threonine kinase TGF-β receptors (TGFBRI and TGFBRII). Ligand binding causes receptor phosphorylation and transmission of the signal to a class of intracellular intermediates, the receptor-regulated SMAD proteins. All TGF-β signaling pathways examined today, from simple organisms to humans, engage two specific receptor-regulated SMAD proteins, the SMAD2 and SMAD3. The C-terminal MH2 domains of the receptor-regulated SMADs are phosphorylated by the intracellular kinase domain of TGF-β receptors (6). The receptor-regulated SMADs then interact with SMAD4 and translocate to the nucleus, where they act as transcriptional regulators (7). Although TGF-β signaling engages the above three SMAD proteins, SMAD2, SMAD3, and SMAD4, overwhelming evidence from in vitro and in vivo studies emphasizes the dominant role of SMAD3 as a mediator of both physiological, homeostatic signaling and of pathophysiological perturbed signaling in all diseases examined to date (1, 2). The SMAD proteins are central nodes in the mechanisms of cross-talk between the TGF-β pathway and other signaling pathways, including the Notch (8) and Wnt (9, 10) signaling pathways.

Phosphorylation of the linker region of receptor-activated SMADs has been shown to inhibit their tumor suppressive function (11). Elevated levels of linker-phosphorylated SMADs represent potential target for pharmaceutical intervention and have been detected in the invasive front of human cancers (12). In fact, these mechanisms have mainly been analyzed in the case of SMAD3 and less for SMAD2. However, in all previous studies, despite its fundamental role in mediating biological effects to TGF-β, SMAD3 was detected using single antibodies. This fails to reveal whether, for example, the linker phosphorylation is integrated into the signaling pathway or is merely present in a subpool of SMAD3 proteins. By applying isPLA with pairs of affinity reagents, including scFv-Fc (Yumabs), we are able to demonstrate that linker-phosphorylated SMAD3 is integrated in a signaling complex with SMAD4. In this study, we first used phage display to isolate antibody fragments from the human naive antibody gene libraries HAL7/8 (13, 14) and expressed these as dimeric, IgG-like affinity reagents for SMAD proteins. The reagents were then used to develop isPLA reactions to screen for modulators of linker phosphorylation of SMADs, conclusively demonstrating the suitability of recombinant antibody fragments for large-scale production of affinity reagents directed against proteins and protein modifications for use in isPLA. Finally, we applied the assays to monitor phosphorylated SMADs in the context of signaling complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant Proteins and Chemicals

Recombinant TGF-β was purchased from Peprotech, Inc. The TGF-β family type I receptor kinase inhibitor GW6604 was synthesized by the Ludwig Cancer Research and dissolved in DMSO (Sigma, Solna, Sweden). CDK4 inhibitor NSC 625987 was purchased from Calbiochem (Solna, Sweden) and dissolved in DMSO according to the manufacturer's instruction. MG132 was purchased from Merck Millipore (Solna, Sweden) and dissolved in DMSO according to the manufacturer's instruction. The Screen-a-well kinase library was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences. The peptides were synthesized within the EU FP7 program AffinityProteome by Dr. Anette Jacobs, German Cancer Research Centre (DKFZ).

Generation of Antibodies against the Identified Antigens

The selection of recombinant antibodies was performed according to (15) with modifications. In short, panning for phages expressing target-binding single chain fragments was performed in 96-well microtiter plates (MTP) (Costar High Binding, Corning, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The wells were coated with 200 ng streptavidin (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) in PBS, pH 7.4, for 1 h at room temperature (21°C), and the wells were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (PAA, Cölbe, Germany) for 1 h or overnight. The biotinylated peptides were incubated with streptavidin-coated plates for 1 h at room temperature in PBS, pH 7.4. In parallel, one well for each panning was blocked with BSA only with no addition of peptides.

2.5 × 1011 phage particles of the human naive antibody gene libraries HAL7 and HAL8 (13, 14) were diluted in PBST with 1% skim milk and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and preincubated for 1 h in a well to which no peptide had been added. The supernatant, containing the depleted library, was transferred to an antigen-coated well and incubated at room temperature for 2 h, followed by 10 washes with PBST. Afterward, bound scFv phage particles were eluted with 200 μl trypsin solution (10 μg/ml trypsin in PBS) at 37 °C for 30 min. The supernatant containing eluted scFv phage particles was transferred into a new tube. Ten microliters of eluted scFv phage were used for titration as described (15). Twenty milliliters Escherichia coli XL1-Blue MRF' (Agilent, Böblingen, Germany) culture in logarithmic growth phase (Optical Density, O.D.600 = 0.4 - 0.5) were infected with the remaining scFv-phage at 37 °C for 30 min without shaking. The infected cells were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 3220 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in 250 μl 2xTY medium, supplemented with 100 mm glucose and 100 μg/ml ampicillin (2xTY-GA), plated on a 15-cm 2xTY agar plate supplemented with 100 mm glucose and 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Colonies were harvested with 5 ml 2xTY-GA. Thirty milliliters of 2xTY-GA were inoculated with 100 μl of the harvested colony suspension and grown to an O.D.600 of 0.4 to 0.5 at 37 °C and 250 rpm. Five milliliters bacterial suspension (∼2.5 × 109 bacteria) were infected with 5 × 1010 helper phage M13K07 (Agilent) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min without shaking, followed by 30 min at 250 rpm. Infected cells were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 3220 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in 30 ml 2xTY, supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin (2xTY-AK). Antibody phages were produced at 30 °C and 250 rpm for 16 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 3220 × g. The supernatant containing the antibody phage (∼1 × 1012 cfu/ml) was directly used for the next panning round or stored at 4 °C for a few days.

Production of scFv in Multi-Tier Micro Plates (MTPs)

Monoclonal binders were identified as described before (16). In brief, 96-well MTPs with polypropylene wells (U96 PP 0.5 ml, Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) containing 150 μl phosphate buffered 2xTY-GA (2xTY-GA supplemented with 10% (v/v) potassium phosphate buffer (0.17 m KH2PO4,0.72 M K2HPO4)) were inoculated with colonies from the titration plate of the third panning round. MTPs were incubated overnight at 37 °C at 1000 rpm in an MTP shaker (Thermoshaker PST-60HL-4, Lab4You, Berlin, Germany). A volume of 180 μl phosphate-buffered 2xTY-GA in each polypropylene-MTP well was inoculated with 10 μl of the overnight culture and grown at 37 °C and 800 rpm for 2 h. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 3220 × g, and 180 μl supernatant were removed. The pellets were resuspended in 180 μl buffered 2xTY supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 100 mm sucrose, and 50 μm isopropyl-beta D thiogalactopyranoside and incubated at 30 °C and 800 rpm overnight. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 3,220 × g and 4 °C. The scFv-containing supernatant was transferred to a new polypropylene-MTP and stored at 4 °C before analysis.

Identification of Monoclonal scFv Using ELISA

Antigen coating was performed as described for the panning procedure. For identification of binders, supernatants containing monoclonal scFv were incubated in the antigen-coated plates for 1.5 h at room temperature followed by three PBST washes. Bound scFv was detected using murine anti-c-myc tag mAb 9E10 and a goat anti-mouse Ig serum, conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Sigma; 1:10,000). The visualization was performed with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate. The staining reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl 1 N sulfuric acid. The absorbance at 450 nm and scattered light at 620 nm were measured, and the 620 nm values were subtracted using a SUNRISE MTP reader (Tecan, Crailsheim, Germany).

Cloning and Production of scFv-Fc

Single-step in-frame cloning of scFv antibody gene fragments into a mammalian expression vector pCSE2.5-hIgG1Fc-XP was performed using the restriction endonucleases NcoI and NotI (New England Biolabs, Inc., Frankfurt, Germany) The resulting vectors pCSE2.5-scFv-hIgG1Fc PAS4-G7, SH527-IIIF2, SH583-IID8, SH544-IIC4, PAS7-C7, PAS7-F9, SH585-IIB5, and SH585-IIC4 were prepared with the NucleoBond Xtra Midi Kit according to the manufacturer's description (Machery-Nagel, Düren, Germany).

Production and Purification of scFv-Fc Antibodies

The scFv-Fc antibodies (Yumabs) were produced as described before (17). In brief, the production was performed in HEK293–6E cells (National Research Council, Biotechnological Research Institute, Montreal, Canada) cultured in the chemically defined medium F17 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) supplemented with 1 g/l Pluronic F68 (Applichem, Darmstadt, Germany), 4 mm l-glutamine (PAA), and 25 mg/l G418 (PAA). Briefly, pCSE2.5-scFv-hIgG1Fc-vectors containing the antibody clones PAS4-G7, SH527-IIIF2, SH583-IID8, SH544-IIC4, PAS7-C7, PAS7-F9, SH585-IIB5, and SH585-IIC4 were transiently transfected into 25 ml HEK293–6E cells in 125 ml Erlenmeyer shake flasks. After 48 h cultivation at 110 rpm in a Minitron orbital shaker (Infors, Bottmingen, Switzerland) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere, one volume culture medium and a final concentration of 0.5% (w/v) of tryptone N1 (TN1, Organotechnie S.A.S., La Courneuve, France) were added. All scFv-hIgG1Fc antibodies were purified via protein A using 1 ml Bio-Scale Mini UNOsphere SUPrA Cartridges and the semiautomated Profinia 2.0 system (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany), according to the standard manufacturer's protocol.

Cell Culture

HaCaT cells were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Sigma), high glucose (25 mm) (Life Technologies) and pretreated with TGF-β receptor signaling antagonist GW6604 at 5 μg/ml for 4 h in order to inhibit autocrine TGF-β signaling. Before ligand stimulation, GW6604 was removed by washing and media change. The cells were stimulated with TGF-β (10 ng/ml) (Invitrogen, Joensuu, Finland) for 1 h. MCF-7 breast epithelial cells were maintained in MEM (Sigma) medium supplemented with 0.01 mg/ml bovine insulin with additional 2 mm l-glutamine, Pen-strep, and 10% FBS (all from Sigma), or alternatively 0.5% FBS for serum-starvation experiments.

The Hs578T cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 0.01 mg/ml bovine insulin with additional 2 mm l-glutamine, Pen-strep, and 10% FBS, or 0.5% FBS for serum-starvation experiments.

isPLA

Cells were grown on eight-well glass slides, fixated with formaldehyde (3%), and analyzed with isPLA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Olink Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden). ScFv was incubated at +4 °C overnight at a concentration of 2 μg/ml. Binders used were anti-SMAD2 (PaS4-G7), anti-SMAD2 (SH527-IIIF2), anti-SMAD3 (SH583-IID8), anti-SMAD4 (PaS7-C7), anti-SMAD4 (PaS7-F9), anti-SMAD7 (H585-IIB5), anti-SMAD7 (SH585-IIC4), anti-pSMAD3 (SH575–3), anti-SMAD2 (SH529-IIIH2), and anti-SMAD2 (SH527-IIA4). For isPLA the recombinant binders were combined with one of the primary antibodies: rabbit anti-TGFRI (V-22, Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany), rabbit anti-SMAD4 (40–0550Z, Invitrogen), mouse anti-SMAD2/3 (610842, BD Transduction Laboratories, Uppsala, Sweden), rabbit anti-SMAD3 (1735–1, Epitomics, Nordic BioSite AB, Täby, Sweden), rabbit anti-SMAD2 (1641–1, Epitomics), rabbit anti-SMAD4 (1676–1, Epitomics), rabbit anti-pSMAD3 (1880–1, Epitomics), or mouse anti-SMAD4 (B-8, Santa Cruz). The incubation was followed by washes in DII Wash Buffer B (Olink Bioscience) and with a 2 h incubation with a combination of anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, or anti-human PLA probes (Olink Bioscience) diluted 1:10 in Duolink antibody diluent (Olink Bioscience). The slides were then washed three times for 5 min with DII Wash Buffer A. The cells were next incubated with Duolink II ligation solution (Olink Bioscience) at 37 °C for 30 min and washed in two changes for 2 min in DII Wash Buffer A. The ligation products were then amplified by rolling circle amplification and detected using Duolink II amplification solution (Olink Bioscience) applied on slides for 90 min at 37 °C. Following isPLA, the cells were washed in TBS-T and counterstained with Alexa Fluor® 488 Phalloidin (Invitrogen) for cytoplasmic staining and Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) for nuclear staining at room temperature for 10 min. The cells were then washed for 20 min in DII Wash Buffer B (Olink Bioscience) and mounted with SlowFade mounting medium (Invitrogen). We used the Cell Profiler software (18) to quantify the levels of p179SMAD3/SMAD4 complexes in nonmitotic cells only since CDK4 inhibitors reduce the numbers of mitotic cells.

Chemical Screen

We stimulated MCF-7 cells with TGF-β in the presence of members of a compound library (ENZO Screen-a-well kinase inhibitor library) at 10 μm, and the wells were analyzed with isPLA using an ImageXpress micro wide-field high content screening system. Images from the total area of each well were obtained as Z-stacks. MetaXpress software was used for image acquisition, and numbers of detection signals were quantified using the Cell Profiler analysis software (18).

RESULTS

Generation of Recombinant Human scFv-Fc Antibodies Directed against SMAD2, SMAD3, SMAD4, and SMAD7

Antibody fragments with affinity for selected peptides of SMAD2, SMAD3, SMAD4, and SMAD7 were isolated from the human naive antibody gene library HAL7/8. Specific binders were identified by antigen recognition in ELISA using soluble scFv fragments (data not shown). scFv genes from selected phages were sequenced and the V region sequences were further analyzed using the VBASE2 database (www.vbase2.org). In total, 85 unique scFvs were generated against SMAD2 (73 sequences), SMAD3 (4 sequences), SMAD4 (4 sequences), and SMAD7 (4 sequences). The antibody fragments and the corresponding SMAD peptides used in this study are identified in Supplemental Table S1. Afterward, the binding specificity of scFv to phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated peptides was analyzed by titration ELISA. Antibody fragments were generated that are specific for either phosphorylated or nonphosphorylated SMAD2 or capable of binding both. An example is shown in Supplemental Fig. S1. The scFvs were recloned into the vector pCSE2.5hIgG1-Fc-XP to produce scFv-Fc (referred to as scFv-Fcs or Yumabs), an IgG-like antibody format, with homodimeric antigen-binding domains and a human IgG1 Fc part (17). The antibodies were produced in HEK293–6E cells and purified using protein A.

Single Chain Binders against SMAD2 and SMAD4 Detect SMAD2/SMAD4 Complex Formation upon TGF-β Stimulation

We employed isPLA to validate the ability of the anti-SMAD4 PAS7-C7 scFv-Fc and anti-SMAD2 PAS4-G7 Yumabs to detect the formation of heterodimers of SMAD2 and SMAD4 (19). Both scFv-Fcs were applied in combination with commercial SMAD2 or SMAD4 monoclonal antibodies. After 1 h of TGF-β stimulation of normal immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaT) cells, we observed increased numbers of isPLA signals, representing interacting SMAD2-SMAD4 proteins. This is in line with the reported kinetics of TGF-β signaling (20) (Fig. 1). Similar results were obtained when scFv-Fcs were used to detect SMAD4 and regular antibodies detected SMAD2 or vice versa as illustrated in (Fig. 2A) where an scFv-Fc was used to detect SMAD2. Additionally, by using a scFv-Fc against SMAD7 (SH585-IIC4), we detected a predominantly cytoplasmic interaction between SMAD7 and the TGF-β type I receptor TGFBRI (TGFRI (V-22), Santa Cruz). TGF- β stimulation increased the levels of SMAD7-TGFBRI interaction events (Fig. 2B).

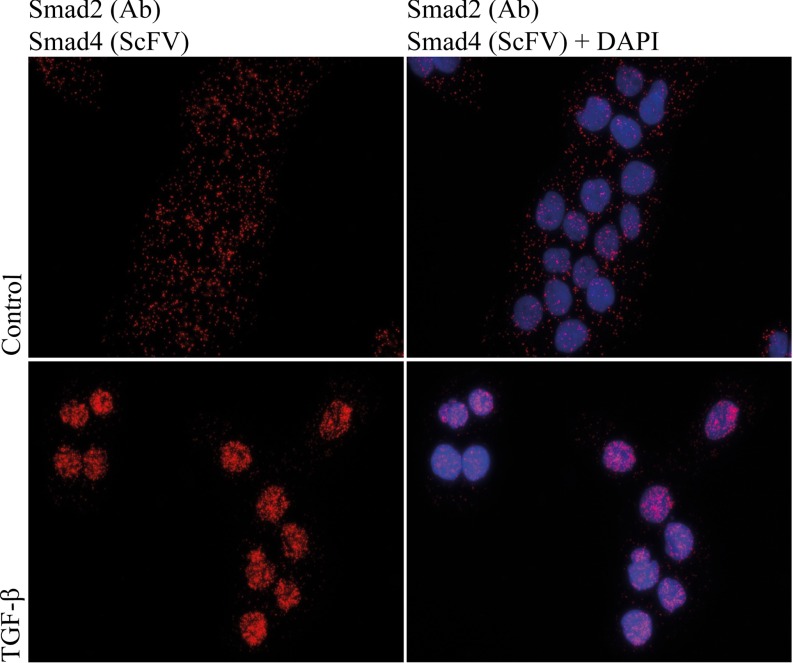

Fig. 1.

isPLA with PAS7-C7 recognizing SMAD4 together with a SMAD2/3 antibody (anti-SMAD2/3, 610842, BD Transduction Laboratories) reveal increased levels of SMAD2-SMAD4 complexes in the nuclei of TGF-β-treated human keratinocytes (HaCaT) cells (C and D) compared with unstimulated controls (A and B). Blue: DAPI-stained nuclei, red: isPLA signals. (A and C) isPLA signals. (B and D) isPLA signals merged with nuclear stain.

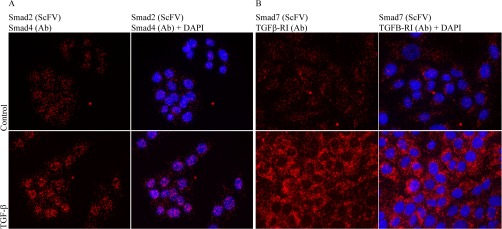

Fig. 2.

isPLA using PAS4-G7 SMAD2 (scFv)-SMAD4 (40–0550Z, Invitrogen) applied on untreated cells or cells treated with TGF-β (10 ng/ml) for 1 h (A). Increased numbers of complexes are detected in the nuclei after TGF-β stimulation. (B) isPLA SMAD7 (SH585-IIC4)-TGFβRI (V-22, Santa Cruz) with or without TGF-β (10 ng/ml) stimulation for 1 h. Blue: DAPI, red: PLA, green: phalloidin.

This expression pattern contrasts with the nuclear staining of SMAD2-SMAD4 complexes and is consistent with the known subcellular localization of the type I receptor and SMAD7 (21).

Increased Levels of Linker-Phosphorylated SMAD3 (p179SMAD3) in Mitotic Cells

As referred to earlier, phosphorylation of SMAD3 in the linker region inhibits its ability to suppress cell proliferation. The phosphorylation has therefore been linked to enhanced progression through the cell cycle and to tumor development (22). This notion has been further substantiated by the finding of increased levels of linker-phosphorylation of SMAD3 in several cancers (20). Therefore, pharmacological intervention that reduces levels of linker-phosphorylated SMAD3 could provide a novel approach to tumor treatment. To investigate the mechanisms of regulation of phosphorylation of SMAD3 in the linker region, we developed a scFv-Fc (SH544-IIC4) directed against the SMAD3 protein, phosphorylated at amino acid threonine 179 in the linker region of the protein (p179SMAD3). Strikingly, we observed high levels of complex formation between SMAD4 and p179SMAD3 in mitotic HaCaT cells (Fig. 3) relative to nonmitotic cells, using isPLA when the p179SMAD3 scFv-Fc antibody was combined with a commercial antibody against SMAD4 (SMAD4, 40–0550Z, Invitrogen).

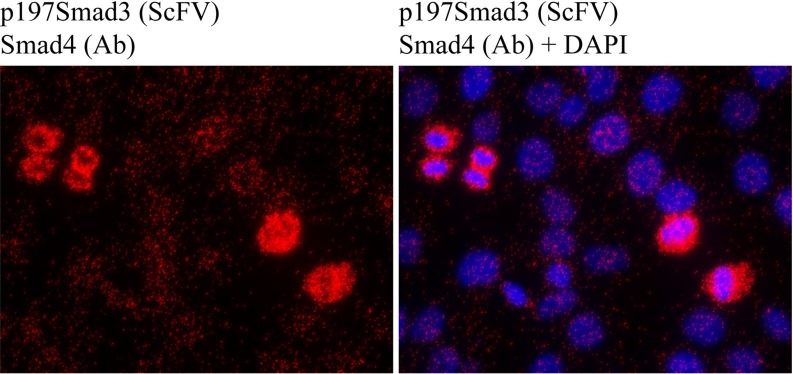

Fig. 3.

isPLA with scFv SH585-IIC4 p179SMAD3 reveals increased levels of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 complexes in mitotic HaCaT cells. Elevated levels of linker-phosphorylated SMAD complexes are predominantly seen in the cytoplasm of mitotic cells. Blue: DAPI, red: PLA, green: phalloidin.

We also observed increased levels of p179SMAD3 in mitotic MCF7 breast cancer cells relative to nonmitotic cells, using isPLA combining the p179SMAD3 SH544-IIC4 with a commercial antibody against SMAD3 (anti-SMAD3, ab40854, Epitomics) (Fig. 4A). To evaluate the ability of p179SMAD3 to interact with SMAD4 in the MCF7 cells, we performed isPLA using SH544-IIC4 in combination with a SMAD4 antibody (SMAD4, 40–0550Z, Invitrogen) (Fig. 4B).Together, these results show that levels of p179SMAD3 are elevated in mitotic MCF7 cells and that p179SMAD3 is able to form a complex with SMAD4. The MCF7 cells were not stimulated with TGF-β. We have previously demonstrated that mitotic cells have reduced levels of SMAD proteins that are phosphorylated in the C-terminal region, which is the transcriptionally active form of the SMADSs (23). Also, overall levels of complexes of SMAD3 and SMAD4 have been shown to be reduced in mitotic cells (23). Here, we show that levels of linker-phosphorylated SMAD3 in complex with SMAD4 are increased in mitotic cells, compared with nonmitotic cells.

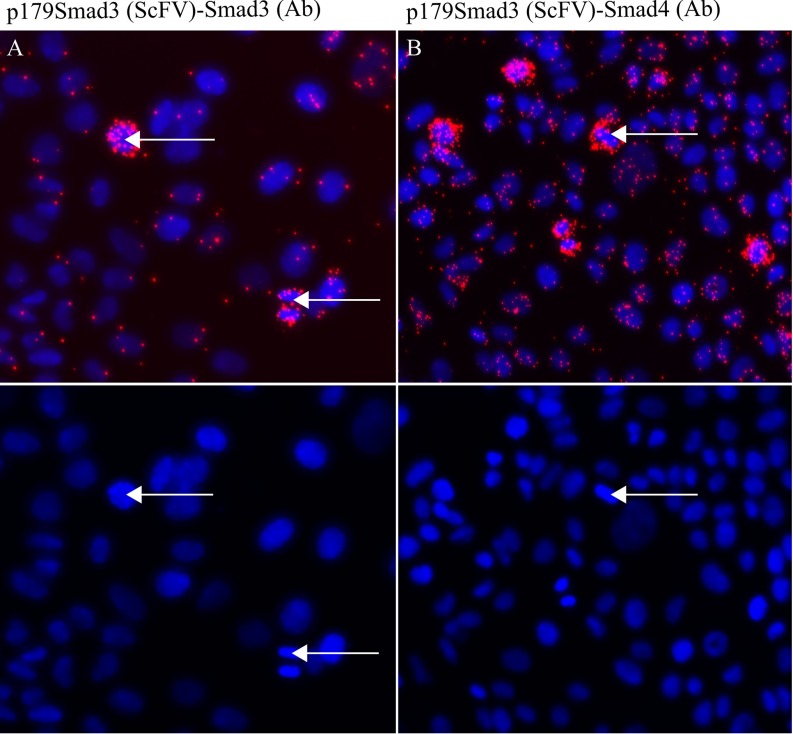

Fig. 4.

isPLA with scFv (SH544-IIC4) against p179SMAD3 in combination with either SMAD3 (1735–1, Epitomics) (A) or SMAD4 (40–0550Z, Invitrogen) (B) demonstrates elevated levels of the p179SMAD3 and increased levels of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 complexes in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Arrows indicate mitotic cells with elevated levels of signals.

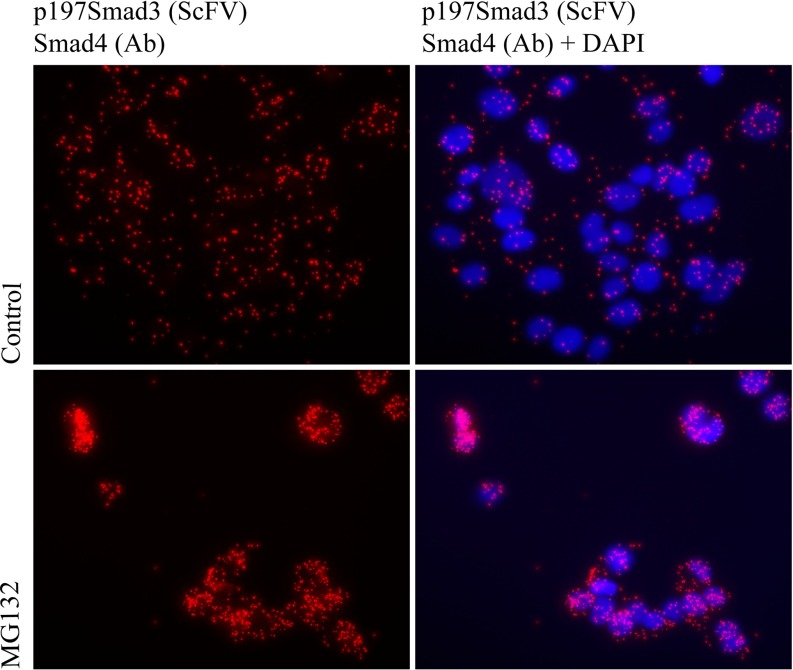

p179SMAD3-SMAD4 Complexes Are Targeted for Proteasomal Degradation

MCF-7 breast cancer cells treated with MG132, a potent and specific inhibitor of the proteasome, exhibited increased levels of p179SMAD3/SMAD4 complexes (Fig. 5). This suggests that the p179SMAD3/SMAD4 complex is bound for degradation by the proteasome. This observation is in line with the overall decrease of SMAD proteins in mitotic cells (23).

Fig. 5.

Proteasomal inhibition causes accumulation of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 complexes in breast cancer cells. Increased levels of complexes were detected in MCF-7 breast cancer cells grown with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μm) for 24 h (A and C) compared with untreated controls (media + DMSO) (B and D) A and B: RCA products only, C and D: RCA products and DAPI.

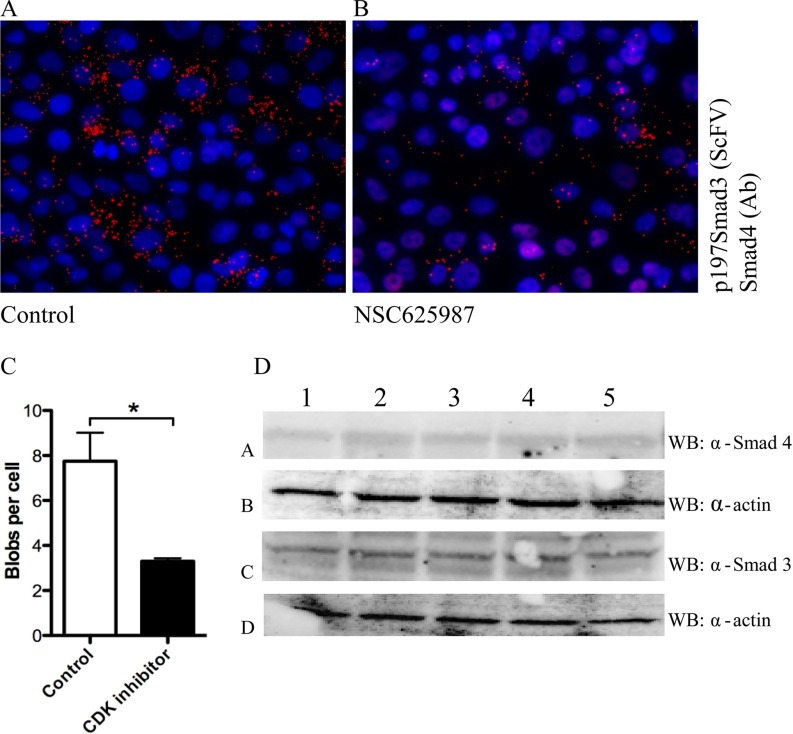

CDK4 Inhibitors Reduce Levels of p179SMAD3

The cyclinD/CDK4 complex is up-regulated in the early phases of the cell cycle (G1 interphase). SMAD3 is a CDK4 substrate, and CDK4 phosphorylation of SMAD3 in the linker region inhibits the transcriptional activity and tumor suppressive function of TGF-β signaling (11). There are currently several clinical trials ongoing with CDK4 inhibitors in combinatorial cancer treatment together with standard cytotoxic drugs (24). Among other effects on the cell cycle, these compounds may also contribute to reducing the levels of linker-phosphorylated SMADs in tumors. To investigate whether pharmacological inhibition of CDK4 reduces the levels of p179SMAD3, we treated MCF-7 breast cancer cells with increasing doses of a specific CDK4 inhibitor, NSC 625987, a compound with 500-fold selectivity for CDK4 over CDK2. We compared the levels of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 signals between nonmitotic cells treated with NSC 625987 and cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) (Figs. 6A and 6B). We limited the comparison to nonmitotic cells because of saturation of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 signals observed in mitotic cells. The number of mitotic cells is low in MCF7 cultures under these conditions. We observed some nuclei with characteristics of mitosis (dense DAPI staining) that were low/negative for p179SMAD3 (Fig. 6A). Although outside the scope of this study, we do not exclude that these cells represent a later stage in mitosis, where the levels of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 complexes may be reduced due to degradation in the proteasome. CDK4 inhibition reduced but did not completely abolish the levels of p179SMAD3, possibly due to other kinases contributing to the phosphorylation at this site (Figs. 6A-6C) (25). Treatment of MCF-7 cells with the CDK4 inhibitor did not affect total levels of SMADs, as shown in Fig. 6D, suggesting that the reduced levels of p179SMAD3 observed upon treatment with the CDK4 inhibitor were due to reduction in phosphorylation of Thr179 and not because of reduced expression of the SMAD proteins. We conclude that pharmacological inhibition of CDK4 caused a decrease in the levels of SMAD3 linker phosphorylation.

Fig. 6.

A selective CDK4 inhibitor (NSC625987) reduces SMAD3 Thr179 linker-phosphorylation in breast cancer cells. Results from isPLA between p179SMAD3 and SMAD4 in MCF7 breast cancer cells treated with the CDK4 inhibitor NSC 625987 (1.2 μm) for 24 h (B) or with vehicle control (DMSO) (A) signals were quantified using the Duolink Tool, n = 3, t test, p = 0.05 (C). Western blot of MCF-7 whole-cell lysates shows that CDK inhibitor (NSC 625987, Calbiochem) treatment did not reduce the total expression of SMAD3 or SMAD4 proteins (D). (1. control (MEM + 0.1% DMSO) 2. NSC 625,987 (200 nm) 3. MEM + 0.4% DMSO. 4. NSC 625,987 (800 nm) 5. MEM + EGF (200 ng/ml for 1 h)).

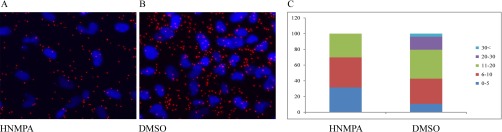

Screen for Compounds that Decrease the Levels of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 Complexes

In order to identify compounds that reduce the levels of p179SMAD3/SMAD4 complexes as potential agents for tumor therapy, we developed a chemical screen with isPLA as a read-out, using the anti-p179SMAD3 scFv-Fc SH544-IIC4 and an SMAD4 antibody (SMAD4, 40–0550Z, Invitrogen). We stimulated MCF-7 cells with a compound library (ENZO Screen-a-well kinase inhibitor library) containing 80 kinase inhibitors with well-defined activities. From this screen, we identified one compound, hydroxy-2-naphthalenylmethylphosphonic acid (HNMPA), which reduced the interaction between p179SMAD3 and SMAD4 in MCF-7 cells by 40%. This result was validated using Hs578t breast cancer cells, which derive from a metastatic cancer. We noticed that HNMPA treatment reduced the subpopulation of cells expressing high numbers of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 complexes (Fig. 7A-7C). HNMPA is known to inhibit the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase. Further, we identified a second compound in the screen; 5-iodotubericidin, capable of reducing p179SMAD3 and SMAD4 interactions (data not shown). Intriguingly, besides effects on the serine/threonine kinase MEK, 5-iodotubericidin, like HNMPA, has been reported to inhibit the insulin receptor.

Fig. 7.

HNMPA reduces levels of p179SMAD3 and SMAD4 complexes in Hs578t breast cancer cells. (A) DMSO control, (B) HNMPA (50 μm), and (C) quantification of isPLA signals per cell with or without inhibitor. HNMPA treatment reduces the subpopulation of cells with the greatest number of detected complexes.

DISCUSSION

We describe the development of scFv-Fcs toward the TGF-β-regulated SMADs 2, 3, 4, and 7 and against a specific phosphorylation site on the linker region of SMAD3. Furthermore, we developed isPLA assays to monitor levels of SMAD complexes in situ using these binders, and we show proof-of-principle experiments establishing that these isPLA assays can be used for pharmacological screens to identify compounds capable of modulating the TGF-β pathway.

The TGF-β pathway in normal cells inhibits the transition from the G1 to the S phase of the cell cycle, thereby preventing cell cycle progression (26). In particular, SMAD3 has an important role in inhibiting cell cycle progression by increasing the expression of the physiological CDK inhibitors p15Ink4b, p21Cip1, and p57Kip2 (1). Phosphorylation of SMAD3 in the linker region down-regulates its transcription promoting activity (11). It is therefore desirable to monitor linker-phosphorylation of SMAD3 in order to follow cellular progression through the cell cycle.

The presence of linker-phosphorylated SMADs at the invasive fronts of colorectal cancers suggests a functional role for SMAD linker phosphorylations in mitotic cancer cells (12). Further, alterations of the TGF-β pathway are of prognostic significance in breast cancer (27). Disrupted expression or mutations of key components such as the TGF-β type II receptors or the SMAD proteins represent common mechanisms for cancer cells to escape the tumor suppressive function of the TGF-β pathway (3). However, in some tumors, SMAD3 expression is maintained. This is true, for example, in breast cancers overexpressing cyclin-D, a highly aggressive subtype of the malignancy (28). Here, we employ recombinant IgG-like Yumabs, expressed from scFv-Fc gene constructs to show that expression of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 complexes are elevated in mitotic breast cancer cells. Therefore, pharmacological inhibition of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 interactions might restore the inhibitory effects of the TGF-β pathway on the cell cycle and thus have potential for cancer treatment. We developed a screening strategy with isPLA as a readout using the anti-p179SMAD3 antibody SH544-IIC4 that we introduce here, together with an antibody directed against SMAD4. This read-out platform can quantify alterations of p179SMAD3 levels in situ, and it has the potential to assign specific properties, i.e. the capacity to restore TGF-β tumor suppression, to compounds selected in a high-throughput screens. In the screens, the p179SMAD3-SMAD4 assay was selected to illustrate the suitability of the PLA method for detection of complexes between two different proteins in a cellular context. In this assay, we did not only detect the complex but also the phosphorylation status of SMAD3. The complex p179SMAD3-SMAD4 would be difficult to quantify in a compound screen by other methods such as Western blotting. We identified two compounds that significantly decreased levels of p179SMAD3/SMAD4 complexes, both previously identified as inhibitors of the insulin receptor, thereby demonstrating the feasibility of the approach. It is possible that the inhibitory effect is mediated via targets other than the insulin receptor, but an intriguing explanation for the observed effects is that the compounds might disrupt a possible cross-talk between the insulin receptor pathway and the TGF-β pathway. Since the proliferation of breast cancer cells requires insulin receptor signaling, the two inhibitory compounds we identified may partially block the cell cycle and thereby impact p179SMAD3/SMAD4 complexes. The possible connection between the insulin and TGF-β receptor pathways is in line with genetic evidence in Caenorhabditis elegans for such a relation (29). The data may thus imply that the insulin receptor pathway either suppresses a phosphatase or induces the activity of a kinase that targets the phosphorylation of Thr 179 in SMAD3. This observation warrants further studies, outside the scope of this work.

In this study, we have demonstrated the development of a set of tools to study the TGF-β/activin SMAD proteins and to screen for drugs affecting signaling via the TGF-β signaling pathway. Recombinant antibody fragments were derived against SMAD proteins and their modifications and used to assess effects upon TGF-β pathway activity via isPLA assays.

Our study establishes that in vitro selected recombinant antibody fragments serve as effective reagents for isPLA with comparable efficiency and selectivity as conventional antibodies (23). They may thus prove generally useful to increase the repertoire of suitable affinity reagents for protein detection via convenient in vitro selection reactions from naïve reagent libraries. Proximity ligation and extension techniques have been shown to permit highly multiplex protein detection, creating a great need for readily produced reagents directed against a very wide range of target proteins and variants thereof, such as the phosphorylated protein targeted herein. Moreover, the application of these assays for reproducible and clinically acceptable applications calls for clonal affinity reagents that can be produced in any desired quantity such as monoclonal antibodies or the recombinant Yumabs developed and applied in this investigation. Recombinant affinity reagents are also ideally suited for conjugation to oligonucleotides as required in proximity reactions since they can be engineered to permit site-directed coupling to exactly one oligonucleotide per affinity reagents, although we used a more conventional conjugation technique herein. The isPLA technique offers a method to simultaneously visualize complex formation between two proteins as well as posttranslational modifications in a biological context such as cells or tissues. Thus, the approach presents an advantage over screening methods that utilize, for example, protein–protein interactions where one recombinant target proteins is immobilized. A disadvantage of isPLA is in scalability; in its present form, the method is suitable for smaller sets of compounds, but because it is more labor intensive, it is poorly suited for high-throughput screening formats. The method thus is more suitable for high-content screening by providing additional information at spatial and temporal resolution of protein–protein interactions and posttranslational modifications in cells.

The data obtained with the scFv-Fc binders support and extend earlier findings about TGF-β signaling. Our main discoveries are that i) the linker-phosphorylated SMAD3 forms a complex with SMAD4, whose levels are increased during mitosis; ii) CDK4 inhibitors reduce these interactions; and iii) treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 increases the levels of p179SMAD3-SMAD4 complexes, suggesting that the complexes normally undergo proteasomal degradation. We also show that the set of SMAD-binding scFv-Fc reagents applied in PLA screens has the potential to identify pharmacological compounds that modulate the TGF-β pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Patricia Schön for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Author contributions: A.B., A.Z., O.S., S.D., and U.L. designed the research; A.B., A.Z., M.H., T.S., S.H., K.G., E.H., A. Moren, and L.C. performed the research; M.H., S.D., and U.L. contributed new reagents or analytic tools; A.B., A.Z., M.H., O.S., A. Moustakas, and U.L. analyzed data; and A.B., A.Z., M.H., A. Moustakas, and U.L. wrote the paper.

* This work was partly supported by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the European Community's 7th Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement n° 222635 (AffinityProteome) 241481 (Affinomics), The Swedish Research Council, Uppsala Berzelii Technology Centre for Neurodiagnostics, Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems, the Swedish Research Council, the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007–2013)/ERC Grant Agreement n. 294409 (ProteinSeq), IngaBritt och Arne Lundbergs Forskningsstiftelse, and Uppsala University. A.B. was also partly supported by the Ludwig institute for cancer research (LICR), and by Swedish Research Council grants NT-E0383401 and MH-K2013-66x-14436-10−5 to A. Moustakas. L.C. was partly supported by LiSUM Ph.D. scholarship.

This article contains supplemental material Supplemental Table S1 and Supplemental Fig. S1.

This article contains supplemental material Supplemental Table S1 and Supplemental Fig. S1.

Disclosure of Financial Interests: U.L. is cofounder of OLINK Biosciences, a company that commercializes PLA techniques. M.H., T.S., and S.D. are cofounders of the YUMAB GmbH, a company offering service and products in the field of antibody engineering.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- CDK4

- cyclin-dependent kinase 4

- Fc

- crystallizable antibody fragments

- isPLA

- in situ proximity ligation assay

- MTP

- Multi-Tier Micro Plate

- p179 SMAD3

- SMAD3 phosphorylated in the linker domain 3

- scFv

- single chain fragment variable

- SMAD

- mothers against decapentaplegic

- TGF-β

- transforming growth factor-β

- TGFBRI

- type I serine/threonine kinase TGF-β receptor

- TGFBRI II

- type II serine/threonine kinase TGF-β receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Heldin C. H., Landström M., and Moustakas A. (2009) Mechanism of TGF-beta signaling to growth arrest, apoptosis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 166–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ikushima H., and Miyazono K. (2010) TGFbeta signalling: A complex web in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 415–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Markowitz S., Wang J., Myeroff L., Parsons R., Sun L., Lutterbaugh J., Fan R. S., Zborowska E., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Brattaln M., and Willson J. K. (1995) Inactivation of the type II TGF-beta receptor in colon cancer cells with microsatellite instability. Science 268, 1336–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stroschein S. L., Wang W., Zhou S., Zhou Q., and Luo K. (1999) Negative feedback regulation of TGF-beta signaling by the SnoN oncoprotein. Science 286, 771–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang S., Hölzel M., Knijnenburg T., Schlicker A., Roepman P., McDermott U., Garnett M., Grernrum W., Sun C., Prahallad A., Groenendijk F. H., Mittempergher L., Nijkamp W., Neefjes J., Salazar R., Ten Dijke P., Uramoto H., Tanaka F., Beijersbergen R. L., Wessels L. F., and Bernards R. (2012) MED12 controls the response to multiple cancer drugs through regulation of TGF-beta receptor signaling. Cell 151, 937–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abdollah S., Macías-Silva M., Tsukazaki T., Hayashi H., Attisano L., and Wrana J. L. (1997) TbetaRI phosphorylation of Smad2 on Ser465 and Ser467 is required for Smad2-Smad4 complex formation and signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27678–27685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen X., Rubock M. J., and Whitman M. (1996) A transcriptional partner for MAD proteins in TGF-beta signalling. Nature 383, 691–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blokzijl A., Dahlqvist C., Reissmann E., Falk A., Moliner A., Lendahl U., and Ibáñez C. F. (2003) Cross-talk between the Notch and TGF-beta signaling pathways mediated by interaction of the Notch intracellular domain with Smad3. J. Cell Biol. 163, 723–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fuentealba L. C., Eivers E., Ikeda A., Hurtado C., Kuroda H., Pera E. M., and De Robertis E. M. (2007) Integrating patterning signals: Wnt/GSK3 regulates the duration of the BMP/Smad1 signal. Cell 131, 980–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guo X., Ramirez A., Waddell D. S., Li Z., Liu X., and Wang X. F. (2008) Axin and GSK3- control Smad3 protein stability and modulate TGF- signaling. Genes Dev. 22, 106–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsuura I., Denissova N. G., Wang G., He D., Long J., and Liu F. (2004) Cyclin-dependent kinases regulate the antiproliferative function of Smads. Nature 430, 226–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matsuzaki K., Kitano C., Murata M., Sekimoto G., Yoshida K., Uemura Y., Seki T., Taketani S., Fujisawa J., and Okazaki K. (2009) Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylated at both linker and COOH-terminal regions transmit malignant TGF-beta signal in later stages of human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 69, 5321–5330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dubel S., Stoevesandt O., Taussig M. J., and Hust M. (2010) Generating recombinant antibodies to the complete human proteome. Trends Biotechnol. 28, 333–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hust M., Meyer T., Voedisch B., Rülker T., Thie H., El-Ghezal A., Kirsch M. I., Schütte M., Helmsing S., Meier D., Schirrmann T., and Dübel S. (2011) A human scFv antibody generation pipeline for proteome research. J. Biotechnol. 152, 159–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frenzel A., Kügler J., Wilke S., Schirrmann T., and Hust M. (2014) Construction of human antibody gene libraries and selection of antibodies by phage display. Methods Mol. Biol. 1060, 215–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hust M., Steinwand M., Al-Halabi L., Helmsing S., Schirrmann T., and Dübel S. (2009) Improved microtitre plate production of single chain Fv fragments in Escherichia coli. N. Biotechnol. 25, 424–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jäger V., Büssow K., Wagner A., Weber S., Hust M., Frenzel A., and Schirrmann T. (2013) High level transient production of recombinant antibodies and antibody fusion proteins in HEK293 cells. BMC Biotechnol. 13, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wählby C., Kamentsky L., Liu Z. H., Riklin-Raviv T., Conery A. L., O'Rourke E. J., Sokolnicki K. L., Visvikis O., Ljosa V., Irazoqui J. E., Golland P., Ruvkun G., Ausubel F. M., and Carpenter A. E. (2012) An image analysis toolbox for high-throughput C. elegans assays. Nat. Methods 9, 714–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Söderberg O., Gullberg M., Jarvius M., Ridderstråle K., Leuchowius K. J., Jarvius J., Wester K., Hydbring P., Bahram F., Larsson L. G., and Landegren U. (2006) Direct observation of individual endogenous protein complexes in situ by proximity ligation. Nat. Methods 3, 995–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zi Z., Chapnick D. A., and Liu X. (2012) Dynamics of TGF-beta/Smad signaling. FEBS Lett. 586, 1921–1928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang L., Zhou F., Drabsch Y., Gao R., Snaar-Jagalska B. E., Mickanin C., Huang H., Sheppard K. A., Porter J. A., Lu C. X., and ten Dijke P. (2012) USP4 is regulated by AKT phosphorylation and directly deubiquitylates TGF-beta type I receptor. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 717–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sekimoto G., Matsuzaki K., Yoshida K., Mori S., Murata M., Seki T., Matsui H., Fujisawa J., and Okazaki K. (2007) Reversible Smad-dependent signaling between tumor suppression and oncogenesis. Cancer Res. 67, 5090–5096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zieba A., Pardali K., Söderberg O., Lindbom L., Nyström E., Moustakas A., Heldin C. H., and Landegren U. (2012) Intercellular variation in signaling through the TGF-beta pathway and its relation to cell density and cell cycle phase. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, M111 013482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rathos M. J., Joshi K., Khanwalkar H., Manohar S. M., and Joshi K. S. (2012) Molecular evidence for increased antitumor activity of gemcitabine in combination with a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, P276–00 in pancreatic cancers. J. Transl. Med. 10, 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alarcón C., Zaromytidou A. I., Xi Q., Gao S., Yu J., Fujisawa S., Barlas A., Miller A. N., Manova-Todorova K., Macias M. J., Sapkota G., Pan D., and Massagué J. (2009) Nuclear CDKs drive Smad transcriptional activation and turnover in BMP and TGF-beta pathways. Cell 139, 757–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iavarone A., and Massagué J. (1997) Repression of the CDK activator Cdc25A and cell-cycle arrest by cytokine TGF-beta in cells lacking the CDK inhibitor p15. Nature 387, 417–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Kruijf E. M., Dekker T. J., Hawinkels L. J., Putter H., Smit V. T., Kroep J. R., Kuppen P. J., van de Velde C. J., ten Dijke P., Tollenaar R. A., and Mesker W. E. (2013) The prognostic role of TGF-beta signaling pathway in breast cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 24, 384–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zelivianski S., Cooley A., Kall R., and Jeruss J. S. (2010) Cyclin-dependent kinase 4-mediated phosphorylation inhibits Smad3 activity in cyclin D-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 8, 1375–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Narasimhan S. D., Yen K., Bansal A., Kwon E. S., Padmanabhan S., and Tissenbaum H. A. (2011) PDP-1 links the TGF-beta and IIS pathways to regulate longevity, development, and metabolism. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.