Abstract

Purpose

Young adult (YA) racial and ethnic minority survivors of cancer (diagnosed ages 18–39) experience significant disparities in health outcomes and survivorship compared to non-minorities of the same age. However, little is known about the survivorship experiences of this population. The purpose of this study is to explore the cancer experiences and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among YA racial/ethnic minorities in an urban US city.

Methods

Racial and ethnic minority YA cancer survivors (0 to 5 years post-treatment) were recruited from a comprehensive cancer center using a purposive sampling approach. Participants (n=31) completed semi-structured interviews, the FACT-G (physical, emotional, social well-being), and the FACIT-Sp (spiritual well-being). Mixed methods data were evaluated using thematic analysis and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

Results

The majority of survivors were women (65%), single (52%) and Hispanic (42%). Across interviews, the most common themes were: “changes in perspective,” “emotional impacts,” “received support,” and “no psychosocial changes.” Other themes varied by racial/ethnic subgroups, including, “treatment effects” (Hispanics), “behavior changes” (Blacks), and “appreciation for life” (Asians). ANCOVAs (controlling for gender and ECOG performance status scores) revealed that race/ethnicity had a significant main effect on emotional (P=0.05), but not physical, social or spiritual HRQOL (P>0.05).

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that minority YA cancer survivors report complex positive and negative experiences. In spite of poor health outcomes, survivors report experiencing growth and positive change due to cancer. Variations in experiences and HRQOL highlight the importance of assessing cultural background to tailor survivorship care among YA racial and ethnic minorities.

Keywords: Health-related quality of life, survivorship, young adult, minority, disparity, cancer

Introduction

Young adults (YAs; ages 18–39) with cancer have been described as medically and psychologically vulnerable, experiencing a greater number of hardships and distinct challenges compared to others with cancer [1–4]. They may be more likely to face geographic relocations, transitions in professional responsibilities and marital or social roles, and fluctuations in academic, financial, and parenting obligations [5–13]. Moreover, the complexities of the YA cancer experience are associated with numerous biological and psychosocial changes. Biological changes including physical changes in height, weight, muscle mass and fluctuating hormones may impact available treatments, therapies, and side effects [1,6,12–15]. Psychosocial changes include cognitive development, psychosocial maturation, awareness of sexual identity, drug and alcohol experimentation, and social pressure to connect with peers [5–8,11].

While White, non-Hispanic YAs have the highest risk of developing cancer, members from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to experience inequities in access to quality care, as well as greater morbidity and mortality [1,2,10]. For example, Hispanic and Black YAs experience higher relapse rates and more severe diagnoses [1], lower levels of cancer-directed surgery and lower rates of radiation following surgery, compared to White-non-Hispanic YAs [16–22]. A diagnosis of cancer may be particularly disruptive for racial/ethnic minority YAs given culturally specific beliefs about cancer including negative beliefs about surgery, fatalism and medical mistrust, which have been shown to contribute to cultural differences in the cancer experiences of patients from racial/ethnic minority groups [18–21]. The literature on adult cancer survivors has shown differences in patient experiences by race/ethnicity related to interpretations of care, differences in expectations, actual provision of care, and the “same care (as non-minority peers), worse experiences” phenomenon [19–23]. In addition, higher likelihood of facing socioeconomic disadvantage may further add stress and contribute to poor health outcomes among minority cancer survivors [15–23]. Nonetheless, other studies have documented certain protective factors related to racial/ethnic minority status derived from health-fostering beliefs, values and practices, and strong family and social networks [17,18,21]. Therefore, the multifaceted impact of racial/ethnic minority status on YAs’ cancer experiences needs to be considered when trying to understand disparities of HRQOL.

Racial/ethnic minority YA cancer survivors face a unique set of conditions that can be considered a “double disparity” [23], wherein they face the challenges of young age and racial/ethnic minority status (e.g., advanced stage at diagnosis, less access to timely treatments, poor quality of care, and poor decision-making supports) [1,2,5,20]. Few studies have examined cancer survivors from both of these underserved groups [1,2,16,19], despite the potential benefits of better understanding this subgroup’s experiences [1,2,13–19]. The purpose of this study was to examine the cancer experiences and HRQOL of racial/ethnic minority YA cancer survivors from a US urban city. We utilized a mixed methods approach to examine survivors’ physical, emotional, social, and spiritual well-being in order to permit a richer and more complete understanding of the YA cancer experience among racial/ethnic minorities.

Methods

We used a purposive sampling approach to identify YA racial/ethnic cancer survivors via review of the electronic medical records at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University. Survivors were recruited via mail/telephone if they met the following eligibility criteria: (a) 18 to 39 years old, (b) from a minority racial/ethnic group, (c) confirmed cancer diagnosis, (d) completed cancer therapy within the past five years, and (e) English-speaking. Study staff obtained consent from interested survivors. We aimed to enroll a minimum of six participants from three racial/ethnic minority groups (Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; Asian/Pacific Islander) to provide a minimum threshold for data saturation achievement within each group [24]. Participants were compensated $25, and study activities were approved under the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Socio-Demographic and Clinical Information

Participants completed socio-demographic, clinical and HRQOL self-report measures (physical, social, emotional and spiritual well-being), and participated in a semi-structured interview designed to elicit post-treatment concerns among YAs not readily captured by standard HRQOL measures. To assess race and ethnicity, participants were asked to indicate if they were of “Hispanic origin, such as Latin American, Mexican, Puerto Rican, or Cuban,” (Yes, No, or Decline to answer). Next participants were asked, “Do you consider yourself…?” (White/Caucasian, Black/African American, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American or Alaskan native, Mixed racial background, Other, or Decline to answer). Additionally, we used the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status to measure patients’ level of functioning with scores from 0 (fully active) to 4 (unable to get out of bed) [25].

Health-related Quality of Life

HRQOL was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) [26]. This 27-item self-report measure scores responses on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much) with a recall period of the past 7 days. Responses are summed to create a total FACT-G score and subscale scores for physical, social, and emotional well-being with higher scores reflecting better HRQOL. Spiritual well-being was measured using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being-12 (FACIT-Sp), a 12-item self-report measure that scores responses on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much) with a recall period of the past 7 days [27]. Responses are summed to create a total FACIT-Sp score with higher scores reflecting better spiritual well-being.

Semi-structured Interviews

Following completion of sociodemographic, clinical, and HRQOL measures, survivors participated in a semi-structured interview designed to elicit post-treatment concerns among YAs not readily captured by standard HRQOL measures. Interviewers followed a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1) adapted from previous interview guides [28] that contained open-ended questions, each with a series of probes, to assess prevalence and correlates of life impacts, physical health behaviors, quality of life, and attitudes about health behavior changes experienced by YA cancer survivors. Individual interviews were completed by phone, lasted 19 to 57 minutes (M=38 minutes), and were conducted by one male and two female interviewers (JMS & BY, early career professionals and social scientists trained in clinical psychology and ARM, an advanced graduate student in public health). All interviewers had prior experience conducting semi-structured interviews and received additional training from a qualitative researcher (DV, a counseling psychologist) prior to data collection.

Analyses

Interviewer audio-recordings were transcribed, de-identified and reviewed by project staff (MAS) to confirm accuracy [29]. Recordings from two of the thirty-one interviews were inaudible; these two participants were excluded from the qualitative analysis. Data were analyzed with NVivo 10.0 software using an inductive, thematic approach [30,31]. Codes were developed in an iterative process whereby three coders (JMS, KK, and ARM) coded several interview transcripts, discussed the codes, and then revised the coding scheme. This process continued until a final set of mutually exclusive and exhaustive codes were agreed upon. Next, two of the three coders (JMS, ARM) coded half of the interviews and inter-rater reliability was examined. Inter-rater reliability ranged between 86% and 99% agreement. The primary coder (ARM) coded the remaining interviews using the established and tested codes. Once all codes were applied, investigators reviewed the coded data and together identified higher-order themes from which individual codes uniquely contributed. Codes were established until data saturation was achieved, or the point at which no new codes were applied during data analysis.

For quantitative data, HRQOL scores from the FACT-G and FACIT-Sp were evaluated for non-normality and transformed using standard procedures to reduce skewness or kurtosis [32]. Demographic and clinical characteristics significantly associated with HRQOL were identified through correlations and t-tests and included as covariates in subsequent Analyses of Covariance (ANCOVAs). Four ANCOVAs were conducted using SPSS version 21[33], evaluating HRQOL score differences (physical, emotional, social, and spiritual) among participants of different racial/ethnic backgrounds.

Results

Sample description

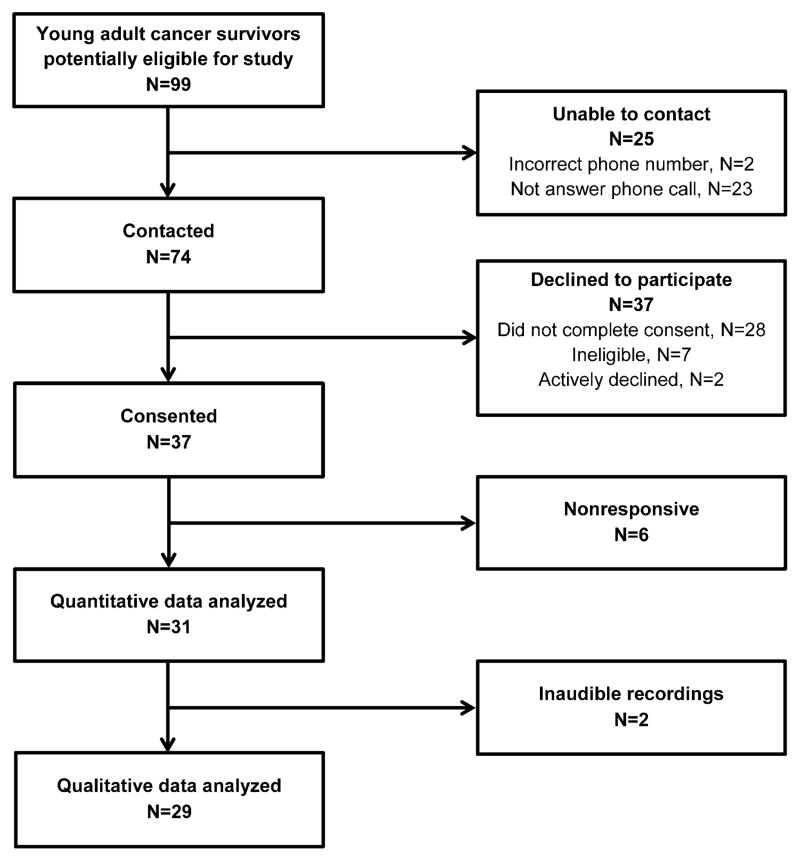

From April 2012 to August 2013, 74 of 99 YA eligible minority cancer survivors were contacted via phone. Of these survivors, thirty-one completed the study interview, for a participation rate of 42% of contacted individuals (Figure 1). The average age of participants was 33 years (range 21–39) and the majority of YAs were women (65%), single (52%) and Hispanic (42%). Although many were currently working full- time (48%), most had stopped working or going to school during their cancer treatment (65%). The most common diagnoses were lymphoma (23%), leukemia (15%) and thyroid cancer (15%). Table 1 includes additional demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

Figure 1.

Recruitment Flow Chart

Table 1.

Demographics of Study Participants (N=31)

| M (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 33.2 (5.1) |

|

| |

| N (%) | |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 13 (42) |

| Race | |

| Black | 9 (29) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 8 (26) |

| Mixed | 3 (10) |

| Other | 5 (16) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 20 (65) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 16 (52) |

| Married | 13 (42) |

| Divorced | 2 (6) |

| Education Completed | |

| Has not graduated from high school | 2 (6) |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 4 (13) |

| Some college | 11 (35) |

| College | 8 (26) |

| Some graduate school | 2 (6) |

| Graduate school | 4 (13) |

| Employment | |

| Full time | 15 (48) |

| Stopped working or school because of cancer | 20 (65) |

| Total household income | |

| $24,999 or less | 8 (26) |

| $25,000 to $74,999 | 7 (23) |

| $75,000 to $149,999 | 10 (33) |

| $150,000 or greater | 6 (19) |

| Primary cancer diagnosis | |

| Lymphoma | 7 (23) |

| Leukemia | 5 (15) |

| Thyroid | 5 (15) |

| Breast | 4 (13) |

| Cervical/Uterine | 4 (13) |

| Other | 6 (19) |

| Time post treatment | |

| 0–12 months | 10(32) |

| 13–24 months | 10(32) |

| 25–60 months | 11(36) |

Semi-structured Interviews (n=29)

Forty codes were developed. No new primary codes emerged after the sixth interview; the most frequently used codes were: “changes in perspective,” “emotional impacts,” “received support” and “no psychosocial changes”. In this paper we chose to highlight these four codes (i.e., themes) in addition to the top codes for each of the three racial/ethnic groups (Table 2), which were, “treatment effects” (most common among Hispanics), “behavior changes” (most common among Black, non-Hispanics), and “appreciation for life” (most common among Asians/Pacific Islanders). Below, we briefly discuss the themes that were shared across groups. Additional examples of quotations for each code can be found in Table 3.

Table 2.

Top five themes by race/ethnicity identified during semi-structured interviews

| Top Themes by Race/Ethnicity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Asian/Pacific Islander | Black non-Hispanic | Hispanic | |

| 1 | Change in perspective | Emotional impact | Emotional impact |

| 2 | No psychosocial changes | Change in perspective | Treatment side effects |

| 3 | Emotional impact | Behavior changes | Received support |

| 4 | Received support | Received support | No psychosocial changes |

| 5 | Appreciation for life | No psychosocial changes | Change in perspective |

Table 3.

Illustrative quotes for common study themes.

| Theme | Quote | Participant |

|---|---|---|

| Changes in Perspective | “I used to be more carefree, but now I am more aware of family, of priorities, and of course health. It [cancer] just opened my eyes.” | Asian/Pacific Islander female |

| “Now I don’t worry about the small things in life.” | Black, non-Hispanic male | |

| “It’s definitely made me a lot more empathetic to those, who have fought cancer, and for the families who’ve lost people through it.” | Hispanic female | |

| Emotional Impacts | “There are days where I’m very emotional. I can’t stop crying. I think back to when I was first diagnosed and moving forward, from the surgery on ‘til today and it saddens me a lot.” | Black, non-Hispanic female |

| “The first few weeks [after my diagnosis] I was in severe denial. Um, I – and I guess once it settled down - I could call it depression.” | Hispanic female | |

| “For the most part I’m, I’m, I’m angry, I’m frustrated, I’m upset.” | Hispanic male | |

| “I was very scared – people coming to see me were saying things to me that you would say to a person you may not ever see again.” | Black, non-Hispanic female | |

| Received Support | “All of my friends were in college where I was studying. So coming here to the hospital in Chicago [meant that] I was away from friends. However, they wrote to me, um, they kept in contact with me over social networks online, so I never felt truly separated from them even though I really was.” | Hispanic female |

| “I needed a lot of family support. I wouldn’t be able to have gone through this all by myself.” | Asian/Pacific Islander female | |

| “My beliefs became stronger because everybody at the church was praying for me and everybody had my back. They were there for me, and when you have somebody that’s there for you, praying for you, keeping your spirit[s] high …sometimes that’s what a person needs going through something like this.” | Black, non-Hispanic male | |

| No Psychosocial Changes | “[Everything] stayed the same because I have a lot of faith in God. I have been in situations before where the faith and strength of God has pulled me out of a situation. I would say that spiritually I didn’t change.” | Asian/Pacific Islander female |

| “Well, I’ve always been a closed kind of person. I really don’t talk about too many things – personal things. If something’s bothering me I’ll keep it inside until it’s really eating at me or bothering me, then I’ll talk about it. But that hasn’t changed.” | Asian/Pacific Islander female | |

| “My goals for the future are still the same no matter what happens. My goals are gonna stay the same, which is my future. I hope that I’ll be married, [and] have, hopefully, God forbid, or God help me, that I have kids of my own.” | Black, non-Hispanic male | |

| Appreciation for Life | “I’m more in the pursuit of happiness than I was before and now I have the realization that time is precious and I should do the things that matter in a way that matters to me.” | Black, non-Hispanic female |

| “Cancer has very much affected my life. Being diagnosed with it, it kind of put me face-to-face with death, I would say, so it changed my life because- or affected my life because life to me has more meaning now.” | Asian/Pacific Islander female | |

| Behavior Changes | “I was smoking cigarettes, and I have not touched a cigarette since my diagnosis day. I don’t eat red meat [anymore]…chicken and fish only. [I] do not drink [alcohol] at all anymore.” | Black, non-Hispanic male |

| I would say that I’m more cognizant of what I eat. [I] probably drink more water now and I didn’t really pay attention to any of those things before I got sick.” | Black, non-Hispanic female | |

| Treatment Effects | “It [cancer] affected me, a lot, in the way that I can no longer have children… I was told a little after treatment they discovered I had, um, like I was pre-menopausal.” | Hispanic female |

| “Yeah, during the treatments I was on, um, high doses of steroids, that would cause a lot of water retention and weight gain. I experienced a lot of aching joints and it was really hard for me to walk and there was a point where, you know, it was even hard to even get my shoes on. The easy task of walking to the washroom became difficult and, you know, for a guy my age it’s pretty embarrassing to ask someone to help you to the washroom and pretty much, hold your hand, you know? It’s not really what you want to be doing but, you know, there’s no other way around it.” | Hispanic male |

Common Themes Across all Races/Ethnicities

Changes in Perspective

YA racial/ethnic minority cancer survivors reported that the process of enduring cancer caused them to experience changes in perspective. Changes in perspective included changes in their views of themselves, their attitudes, their views of cancer, and their lifetime priorities:

“Now I don’t worry about the small things in life.”

– Black, non-Hispanic male participant.

Emotional Impacts

The emotional impacts theme consisted of a variety of feelings including: fear, sadness, worry, denial, depression, anger or anxiety. This theme was used when participants described general emotional sequela from the cancer diagnosis and treatment:

“I was very scared – people coming to see me were saying things to me that you would say to a person you may not ever see again.”

– Black, non-Hispanic female participant.

Received Support

Participants from all racial/ethnic groups reported that their peer and family social networks helped them recover, manage and adjust to the cancer experience. These participants discussed their cancer experience and how they connected to friends and strangers using social networking sites, connected in-person with family and friends, and participated in religious or spiritual activities such as attending worship services:

“All of my friends were in college where I was studying. So coming here to the hospital in Chicago [meant that] I was away from friends. However, they wrote to me, um, they kept in contact with me over social networks online, so I never felt truly separated from them even though I really was.”

– Hispanic female participant.

No Psychosocial Changes

In contrast to YA racial/ethnic minority survivors who reported many psychosocial changes, such as emotional impacts, and changes in perspectives, some reported experiencing no psychosocial changes. Some YA minority survivors explained that the cancer experience did not impact the way they experienced life issues, including their thoughts, attitudes, behaviors and interactions:

“You would think it [cancer] has had a bigger effect on my life; but not actually. It’s been a few months, and I’m back into the swing of things. It hasn’t really changed a whole lot.”

– Asian/Pacific Islander male participant.

Themes by Race/Ethnicity

While the above themes were common among survivors from all racial/ethnic backgrounds, other themes – including appreciation for life, behavior changes, and treatment effects—were more common among specific subgroups. Table 3 provides additional quotes by theme.

Appreciation for Life – Asian/Pacific Islander

Despite many challenges faced by YA cancer survivors, this theme encompassed a newfound appreciation for life, a positive attitude towards their future, and a sense of personal growth. This term was applied when participants described a sense of gratitude and life appreciation post-cancer that may be expressed through enjoying the “little things”:

“Cancer has very much affected my life. Being diagnosed with it, it kind of put me face-to-face with death, I would say, so it changed my life because- or affected my life because life to me has more meaning now,” – Asian/Pacific Islander female participant.

Behavior Changes – Black, non-Hispanic

After a cancer diagnosis, YAs reported making behavior changes including: improved dietary choices, decreased alcohol consumption, or increased physical activity levels. This theme was used when participants commented on how they’ve made positive changes in their health behaviors:

“I was smoking cigarettes, and I have not touched a cigarette since my diagnosis day. I don’t eat red meat [anymore]…chicken and fish only. [I] do not drink [alcohol] at all anymore,”

– Black, non-Hispanic male participant.

Treatment Effects – Hispanics

The cancer experience may result in treatment side effects. This theme included managing treatment side effects (e.g. neuropathy, hair loss, and fertility issues) or noting impacts to physical or mental functioning, body appearance, fertility/sexual functioning, or well-being due to treatment:

“It [cancer] affected me, a lot, in the way that I can no longer have children… I was told a little after treatment they discovered I had, um, like I was pre-menopausal.”

– Hispanic female participant.

FACT-G and FACIT-Sp (n=31)

Next, a series of ANCOVAs were conducted to determine significant differences in HRQOL scores between participants of different racial/ethnic backgrounds and to complement our qualitative findings (Table 4). Only two demographic and clinical variables were associated with HRQOL. Performance status was associated with physical well-being (r=−.48, P=.006). Gender was associated with spiritual (t(27)=−3.33, P=.003) and emotional well-being (t(29)=−2.38; P=.024) with women reporting lower levels of spiritual (M=35.55, SD=10.14) and emotional well-being (M=18.70, SD=2.90) compared to men (M=44.00, SD=3.79; and M=21.36, SD=3.14; respectively). Thus, both gender and performance status were used as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Table 4.

One-way ANCOVAs of the relationship between Race/Ethnicity and QOL

| QOL Domain | F (df) | Significance | Total R2 | Race/Ethnicity | Mean | Std. Error | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Well-Being | F(2,25)=2.02 | p=.15 | 33.2% | Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.74 | .101 | 1.53–1.95 |

| Black/Non-Hispanic | 1.80 | .096 | 1.60–2.00 | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.56 | .079 | 1.40–1.73 | ||||

| Emotional Well-Being | F(2,25)=3.29 | p=.05 | 41.6% | Asian/Pacific Islander | 21.44 | .955 | 19.47–23.41 |

| Black/Non-Hispanic | 19.78 | .907 | 17.91–21.64 | ||||

| Hispanic | 18.35 | .747 | 16.81–19.88 | ||||

| Social Well-Being | F(2,25)=0.01 | p=.99 | 7.6% | Asian/Pacific Islander | 22.61 | 1.96 | 18.58–26.64 |

| Black/Non-Hispanic | 22.37 | 1.86 | 18.54–26.20 | ||||

| Hispanic | 22.21 | 1.53 | 19.06–25.37 | ||||

| Spiritual Well-Being | F(2,25)=1.25 | p=.303 | 33.0% | Asian/Pacific Islander | 40.25 | 2.98 | 34.12–46.39 |

| Black/Non-Hispanic | 41.07 | 2.83 | 35.24–46.90 | ||||

| Hispanic | 35.80 | 2.33 | 31.00–40.59 |

Note: Covariates included in each of the ANCOVAs were gender and ECOG performance status; physical well-being residuals were not normally distributed and so the physical well-being outcomes were reflected and transformed using logarithmic (Log10) methods to account for negatively skewed distributions.

In general, participants mean HRQOL scores varied by race with Asian/Pacific Islanders reporting the best HRQOL scores, followed by Black, non-Hispanics, and Hispanics. ANCOVA results yielded a trend for emotional HRQOL (P=.05), with Asian/Pacific Islanders reporting better HRQOL scores than Hispanics. No differences by race were reported for physical, social or spiritual HRQOL (all P>.05).

Discussion

YA racial/ethnic minorities suffer disproportionately from cancer. Our findings contribute to an increased understanding of the cancer experience and HRQOL among racial/ethnic minority YA cancer survivors living in an urban US city. Our qualitative findings underscore common experiences among racial/ethnic minority YA participants such as changes in life perspective and emotional impacts. They also identified aspects of the cancer experience that appeared more prominent among different racial/ethnic minority groups including treatment side effects and changes in health behaviors. Although the sample size was small, our quantitative findings suggested that YA Asian/Pacific Islanders reported higher levels of emotional HRQOL compared to Hispanics. Altogether, findings suggest that cancer does not uniformly affect areas of life in positive or negative ways. Examining the YA racial/ethnic cancer experience and HRQOL is an important context worth understanding more fully.

Qualitative findings revealed that while a variety of themes emerged in semi-structured interviews, the most common among participants from all races/ethnicities, included: changes in perspectives as well as no psychosocial changes, emotional impacts, and received support. Study participants reported difficulty navigating developmental milestones consistent with findings from YA cancer survivors [5–7], such as establishing autonomy from parents, setting personal and professional goals, developing a sense of identity, and building strong, intimate relationships. In the face of these difficulties, some YA racial/ethnic minority survivors reported the challenges and distress from cancer changed their lives, identity and outlook on the future. In contrast, some YAs in our study admitted the cancer experience was not particularly disruptive and they experienced no changes in their lives. Conflicting accounts from YAs may be further explained by developmental transitions limiting YAs from fully understanding or accepting their experience [7,9,11]. As such, it is likely that frequent reports of both no changes and changes in life perspective are simply a function of the normal range of experiences for YAs with cancer [12,34].

The “emotional impacts” of cancer among YAs are especially complex given the unique physiological changes in the body, including changes in cognition that shape the interpretation of cancer [5,6]. Many survivors reported feeling depressed, angry, anxious, or shocked, causing them to feel different from their peers. Kwak et al. found distress symptoms in YA cancer patients exceeded population norms [35], underscoring the significant role of the emotional impact of cancer among YAs. In our interviews, most of the participants reported a reliance on “received support,” especially from family. Previous literature describes how YAs with cancer value support and dynamic social networks [1,2,36–37]. Peer relationships are often complicated by the cancer experience, as YAs may be unable to attend normal educational and extracurricular activities, which may isolate them from peers [1,2], and periods of long hospitalization may impair peer relationships [6–8, 36–37]. YAs in our study discussed how the cancer experience caused difficulties in maintaining relationships, and stressed the importance in receiving support from family and friends and the reliance on members of their church as an extension of family.

Other themes were mentioned that varied by racial/ethnic group including “appreciation for life,” “behavior changes” and “treatment effects” – themes that were complemented by our quantitative findings. As YA survivors discussed their cancer experiences, the theme “appreciation for life” or a positive orientation towards the future emerged prominently among YA Asian/Pacific Islander survivors. All participants who identified this theme talked about adopting a new sense of hope, self-efficacy, autonomy, and increased confidence. These themes are complemented by the higher emotional well-being scores of our Asian YA survivors and research among adolescent cancer survivors, suggesting benefit finding/meaning making is related with positive psychosocial well-being post-treatment [34,38–40]. Moreover, in older (40+ year-old) cancer survivors, Asian Americans have reported better HRQOL than other groups including White non-Hispanic individuals [18,19]. This may reflect cultural differences in describing adverse events [39,40] but it is also true that racial and ethnic minorities from higher SES status report being more proactive, accepting the illness and having a more positive attitude [38,40].

During interviews, Black, non-Hispanic participants reported positive “behavior changes” taking place as a result of the cancer experience. These positive changes included increased physical activity, improved diet, and reduced tobacco use. Although not statistically significant, the physical well-being scores among Black, non-Hispanic participants were the highest of the racial/ethnic minority groups, indicating they felt positive about their health status. A cancer diagnosis may provide a teachable moment facilitating the adoption of healthier lifestyle choices associated with a lower risk for cancer and improved health [41]. We are not clear why participants made specific behavior changes in this study, but it is possible the information provided to YA patients during their cancer experience encouraged healthy lifestyle modifications.

Hispanics were the most vocal about the negative issues related to the cancer treatment. YA Hispanics reported concerns about the “physical effects from treatment” including: infertility, scarring, premature menopause, and neuropathy. Physical HRQOL scores were also the lowest among our Hispanic YA survivors, which corresponds with other published findings [38–40,42]. A 2011 systematic review indicated Hispanic cancer survivors reported significantly worse distress, depression, social HRQOL and overall HRQOL than survivors from other racial/ethnic groups [42]. Although we cannot rule out the potential that these findings were secondary to aggressive treatments and late effects, these results suggest that Hispanics may be at risk for poor HRQOL and difficulty adjusting to survivorship. There is a need to provide YA Hispanic survivors with information, support and resources to assist their transition after diagnosis and through survivorship.

This study has some limitations. We did not ask participants about the impact of their racial/ethnic minority status on the cancer experience or HRQOL and our participants were English-speaking, which prevented us from learning about the experiences of less acculturated racial/ethnic minority survivors who face unique health disparities. Similarly, our sample was recruited at an urban comprehensive cancer center and had relatively high levels of socioeconomic status. Therefore, caution should be taken in generalizing our results to other populations, including those with lower socioeconomic status. Additionally, there is the potential for selection bias within this study because we do not know what proportion of participants were excluded because they did not self-report as a racial/ethnic minority or were too unwell to participate. We also did not account for patient treatment history so we cannot determine if findings were associated with treatment type. Further, the cross-sectional sample was small and participants engaged in retrospective recall, some describing events occurring up to five years ago. However, in qualitative research, important insights can be gleaned from small samples, and descriptive studies serve a vital role in building knowledge base where research is relatively sparse by identifying issues salient to an understudied patient population and informing much-needed observational and intervention research.

This is the first study to use a mixed methods approach to provide a broad description of HRQOL and explore experiences of cancer among YA racial/ethnic minority survivors. Future research should include larger, prospective, longitudinal studies to assess and better understand HRQOL from diagnosis through treatment and survivorship. Future studies will offer an opportunity to discern whether differences reported in qualitative and HRQOL findings are attributable to cultural influences, age/developmental status, or some unique combination of both. Findings will help inform developmentally and culturally sensitive issues with tailored approaches such as supportive care plans, and provide patient-centered care for YA racial/ethnic minority survivors. These patient-centered strategies may minimize negative HRQOL and cancer experiences, and improve outcomes for this underserved group of cancer survivors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the young adult cancer survivors who participated in the research project and shared their views and experiences. The authors would also like to thank Jennifer Beaumont for providing her expertise on the analyses for the quantitative data.

Funding Source: Research reported in this publication was supported by the American Cancer Society-Illinois Division under award number PSB-08-15, the National Cancer Institute of the NIH under award number K07CA158008, and a portion of Dr. Garcia’s time was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number U54AR057951-S1. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report. We have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to view the data if requested.

References

- 1.Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; and the LiveSTRONG Young Adult Alliance; Aug, 2006. [Accessed October 21, 2014]. Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer, Report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. NIH Publication No. 06-6067. http:s/planning.cancer.gov/library/AYAO_PRG_Report_2006_FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleyer WA, O’Leary M, Barr R, Ries LAG, editors. Cancer epidemiology in older adolescents and young adults 15 to 29 years of age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975–2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006. NIH Pub. No. 06–5767. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniel LC, Barakat LP, Brumley LD, Schwartz LA. Health-related hindrance of personal goals of adolescents with cancer: the role of the interaction of race/ethnicity and income. J Clin Psych in Med Settings. 2014;21(2):155–164. doi: 10.1007/s10880-014-9390-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute at the National Institute of Health. [Accessed January 7, 2015];A snapshot of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers. www.cancer.gov/researchandfunding/snapshots/adolescent-you-adult. Updated November 5, 2014.

- 5.Quinn GP, Gonçalves V, Sehovic I, Bowman ML, Reed DR. Quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Patient Related Outcome Measures. 2015;6:19–51. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S51658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan S, Davies S, Palmer S, Plaster M. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’roll: caring for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4825–4830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zebrack B, Isaacson S. Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1221–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oeffinger KC, Tonorezos ES. The cancer is over, now what? Understanding risk, changing outcomes. Cancer. 2011;117(S10):2250–2257. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zebrack B. Patient-centered research to inform patient-centered care for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2227–2229. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan TH, Zebrack B, Chen VW, Neale AV, et al. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in the United States: The adolescent and young adult health outcomes and patient experience study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(17):2136–2148. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Agostino NM, Penney A, Zebrack B. Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117(S10):2329–2334. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salsman JM, Garcia SF, Yanez B, Sanford SD, Snyder MA, Victorson D. Physical, emotional, and social health differences between posttreatment young adults with cancer and matched healthy controls. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2247–2254. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bleyer A, Barr R, Hayes-Lattin B, Thomas D, Ellis C, Anderson B. The distinctive biology of cancer in adolescents and young adults. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2008;8(4):288–298. doi: 10.1038/nrc2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiener L, Weaver MS, Bell CJ, Sansom-Daly UM. Threading the cloak: Palliative care education for care providers of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Clin oncol adolesc young adults. 2015;9(5):1–18. doi: 10.2147/COAYA.S49176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linabery AM, Ross JA. Childhood and adolescent cancer survival in the US by race and ethnicity for the diagnostic period 1975–1999. Cancer. 2008;113(9):2575–2596. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shavers VL, Harian LC, Stevens JL. Racial/ethnic variation in clinical presentation, treatment, and survival among breast cancer patients under age 35. Cancer. 2003;97(1):134–137. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker KS, Anderson JR, Lobe TE, Wharam MD, Qualman SJ, Raney RB, et al. Children from ethnic minorities have benefited equally as other children from contemporary therapy for rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(22):4428–4433. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mead N, Roland M. Understanding why some ethnic minority patients evaluate medical care more negatively than white patients: a cross sectional analysis of a routine patient survey in English general practices. Brit Med J. 2009;339:b3450. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin JJ, Mhango G, Wall MM, Lurslurchachai L, Bond KT, Nelson JE, Wisnivesky JP. Cultural Factors Associated with Racial Disparities in Lung Cancer Care. Ann Amer Thor Soc. 2014;11(4):489–495. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201402-055OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buki LP, Garces DM, Hinestrosa MC, Kogan L, Carrillo IY, French B. Latina breast cancer survivors’ lived experiences: diagnosis, treatment and beyond. Cult Divers Ethn Min. 2008;14(2):163–167. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallo LC, Penedo FJ, Espinosa de los Monteros K, Arguelles W. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? J Pers. 2009;77(6):1707–1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews KA, Gallo LC. Psychological perspectives on pathways linking socioeconomic status and physical health. Annu Rev Psych. 2011;62:501–530. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson S, Zhang H, Jiang C, Burwell K, Rehr R, Murray R, et al. Being overburdened and medically underserved: assessment of this double disparity for populations in the state of Maryland. Environ Health. 2014;13(1):26–38. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-13-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field meth. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Amer J Clinl Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai JS, Garcia SF, Salsman JM, Rosenbloom S, Cella D. The psychosocial impact of cancer: Evidence in support of independent general positive and negative components. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(2):195–207. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9935-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glaser BG. Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Vol. 2. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richards L. Using NVivo in qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.M Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; Released 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellizzi KM, Smith A, Schmidt S, Keegan TH, Zebrack B, Lynch CF, et al. Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer. 2012;118(20):5155–5162. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwak M, Zebrack BJ, Meeske KA, Embry L, Aguilar C, Block R, et al. Trajectories of psychological distress in adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: a 1-year longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(17):2160–2166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kent EE, Smith AW, Keegan TH, Lynch CF, Wu XC, Hamilton AS. Talking about cancer and meeting peer survivors: social information needs of adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer. J Adol Yng Adult Oncol. 2012;2(2):44–52. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2012.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrari A, Thomas D, Franklin AR, Hayes-Lattin BM, Mascarin M, van der Graaf W, et al. Starting an adolescent and young adult program: some success stories and some obstacles to overcome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4850–4857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maly RC, Liu Y, Liang LJ, Ganz PA. Quality of life over 5 years after a breast cancer diagnosis among low-income women: Effects of race/ethnicity and patient-physician communication. Cancer. 2014;121(6):916–926. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luckett T, Goldstein D, Butow PN, Gebski V, Aldridge LJ, McGrane J, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(13):1240–1248. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kraemer J, Wright K, Coscarelli A, Clayton S, Williams I, Hills D. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: A qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol. 2004;13(6):408–28. doi: 10.1002/pon.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell MK, Carr C, DeVellis B, Switzer B, Biddle AM, Amamoo A, et al. A randomized trial of tailoring and motivational interviewing to promote fruit and vegetable consumption for cancer prevention and control. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(2):71–85. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yanez B, Thompson EH, Stanton AL. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(2):191–207. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.