Abstract

Background

This study examined the bidirectional nature of mother-infant positive and negative emotional displays during social interaction across multiple tasks, among postpartum women accounting for childhood maltreatment severity. Additionally, effects of maternal postpartum psychopathology on maternal affect and effects of task and emotional valence on dyadic emotional displays were also evaluated.

Sampling and Methods

192 mother-infant dyads (51% male infants) were videotaped during free play and the Still-Face paradigm at 6 months postpartum. Mothers reported on trauma history and postpartum depression and PTSD symptoms. Reliable, masked coders scored maternal and infant positive and negative affect from the videotaped interactions.

Results

Three path models evaluated whether dyadic affective displays were primarily mother-driven, infant-driven, or bidirectional in nature, adjusting for mothers’ maltreatment severity and postpartum psychopathology. The bidirectional model had the best fit. Child maltreatment severity predicted depression and PTSD symptoms, and maternal symptoms predicted affective displays (both positive and negative), but the pattern differed for depressive symptoms compared to PTSD symptoms. Emotional valence and task altered the nature of bidirectional affective displays.

Conclusions

The results add to our understanding of dyadic affective exchanges in the context of maternal risk (i.e., childhood maltreatment history, postpartum symptoms of depression and PTSD). Findings highlight postpartum depression symptoms as one mechanism of risk transmission from maternal maltreatment history to impacted parent-child interactions. Limitations include reliance on self-reported psychological symptoms and that the sample size prohibited testing of moderation analyses. Developmental and clinical implications are discussed.

Keywords: Mother-infant affective exchanges, dyadic affect, postpartum depression symptoms, postpartum PTSD symptoms, childhood maltreatment history

Introduction

Emotional expressions are a primary way parents and infants communicate, and the manner in which parents and infants exchange and share emotions during social interactions is critical for the quality of their dynamic communication [1]. Infants’ discrete displays of emotions communicate important information about their changing states and goals to parents and elicit parental behaviors that help organize infants’ arousal and behavior [2]. Furthermore, parents’ sensitive, contingent reactions to infants’ emotional displays scaffold infants’ emerging self-regulatory abilities to manage their emotions and behaviors [3–5]. As maturation proceeds, the child moves from primary co-regulation through parent-infant affective exchanges to increased self-regulation, and thus the quality of the early parent-infant affective exchanges is often understood to lay a foundation for the quality of subsequent child social, emotional, and psychological self-regulation [4,6]. Given the importance of dyadic affective exchanges in early infancy for healthy child development, a principal aim of this study is to better understand the nature of these affective exchanges between mothers and their infants.

We take two primary approaches to understanding these early mother-infant emotional exchanges. First, we examine mother-infant dyadic affective exchanges with a focus on the role of maternal psychological vulnerability as this may interfere with the mother’s ability to effectively “decode” the infant’s emotional signaling and prevent her from responding sensitively, potentially undermining healthy child development of emotional self-regulation. We further examined the influence of maternal maltreatment severity on maternal psychopathology. We therefore examine mother-infant affective exchanges in mothers accounting for childhood maltreatment severity and postpartum psychopathology [i.e., depression and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder symptoms (PTSD)]. Secondly, responsive to prior research that has identified the possibility of child, parent and bidirectional driven effects in mother-infant emotional exchanges, in the current study we directly examine both unidirectional and bidirectional effects in our sample rather than simply relying on unidirectional (typically mother-driven) models.

History of childhood maltreatment and postpartum psychopathology

The postpartum period may be a particularly relevant time to study vulnerable mothers given that it is a time of transition and heightened risk for mental health difficulties [7,8], particularly for those with previous trauma exposure [9]. Mothers who have experienced childhood maltreatment are more likely than mothers without maltreatment histories to be at risk for postpartum depression and PTSD symptoms [10–12], and their infants are more likely to show less optimal behavioral and biological (cortisol) stress regulation [13]. While genetic and epigenetic factors may account for part of this intergenerational transmission [14], it is also possible that alteration in mother-infant affective exchanges during postpartum contribute to such outcomes. In support of this assumption are findings that a constricted range of maternal affectivity, as often manifest in mothers with high levels of depressive symptomology, undermines sensitive responsiveness to the infant affective bids [13]. However, far less is known about associations with mother’s childhood maltreatment severity and/or PTSD.

Dyadic bidirectional exchanges of emotional displays

The active role of infants in affective exchanges seems supported by the fact that infants as young as 6 months can discriminate positive and negative facial expressions and can utilize such emotional displays from others to help them interpret and react to ambiguous situations by 12 months of age [15]. Tronick et al.’s, Mutual Regulation Model [1] proposes that coordinated affective states between a mother and her infant are associated with more positive affect during the interaction, whereas lack of interactive coordination is associated with more negative affect. Consistently, research suggests that mother-infant bidirectional (shared) positive affectivity may be more beneficial for child well-being than a mother’s unidirectional positive affective displays alone [6,16].

Given the relational context within which young infants learn about emotional displays and regulation [17], the postpartum period is particularly critical for the establishment of affective communication patterns within the mother-infant dyad. It is conceivable that infants of mothers with depression and/or PTSD symptoms, may “mirror” their mothers altered affective exchanges and similarly display altered emotionality during exchanges [18,19], contributing to perturbed bi-directional exchanges. Thus, we thought it particularly important to study the nature of these bi-directional affective exchanges between mothers and infants in a sample of mothers with high rates of childhood maltreatment and postpartum symptomology.

Importantly, because the context of interactional exchange may affect the nature of displays and effects, in the present study we utilize both a low challenge, unstructured free play interaction, as well as higher challenge, structured interactive task, the “Still Face Paradigm” (SFP; 20). The SFP has been widely utilized both in healthy mothers and mothers with depression [19,21], and a smaller number of studies with mothers with PTSD [18,22], and overall is a valid measure to tap into interactive affective exchanges [23]. Further, research has documented that infant and mother behavior varies by type of interactive task and that more challenging tasks tend to pull for more individual differences in behavior as well as more negative maternal behaviors (24).

In summary, the present paper extends prior work by examining maternal and infant displays of positive and negative affect during social interactions, both concurrently and prospectively, across four interactive episodes at six months postpartum, in a sample of mothers with heightened risk due to childhood adversity and current symptomology (i.e., depression and PTSD symptoms concurrently).

Our first and main aim was to determine whether the positive or negative affective exchanges between a mother and her infant are primarily “driven” by the mother or by the infant, or whether they are best characterized as “bidirectional.” Based on prior research (1,16), we hypothesized that the bidirectional models would better explain affective displays between mothers and infants compared to either mother-or child-driven models. Our second aim was to explore the impact of childhood maltreatment history on maternal postpartum symptoms of depression and PTSD. We hypothesized that childhood maltreatment severity would be positively related to postpartum depression and PTSD symptoms. Our third aim was to examine the effect of mothers’ concurrent symptoms of postpartum depression and PTSD on maternal affective displays. Based on research documenting a positive relation between maternal depression and negative affect (and the inverse for positive affect; 25), we hypothesized that maternal depressive symptoms would predict higher negative and lower positive affect. Given the paucity of prior research, we did not pose an a priori hypothesis for mothers’ PTSD symptoms on maternal affective displays. Our fourth aim was to examine the effects of dyadic emotional valence (positive vs. negative) and task (free play vs. a stress inducing task) on dyadic affective displays. Here we hypothesized, based on the Mutual Regulation Model [1], that affective coordination (i.e., frequency of significant compared to non-significant relations between mother-infant same valence affect) would be stronger for positive dyadic emotional valence than for negative. Regarding task effects on dyadic affective exchanges, we hypothesized that the more stressful task (SFP) would result in stronger dyadic negative affect than the less stressful (free play) task [24].

Method

Participants

Analyses were based on data collected for 192 mother-infant dyads (51% male infants) who completed the 6-month home visit in a larger ongoing longitudinal project (N = 268), Maternal Anxiety during the Childbearing Years (MACY study, NIMH MH080147). The goal of the MACY project was to evaluate the effects of mothers’ childhood maltreatment histories on mothers’ postpartum adaptation, parenting, and child outcomes. Mothers were recruited in two ways: 1) completion of a prior study examining PTSD on childbearing experiences (26), or 2) via community advertisements [22]. Eligible mothers had to be at least 18 years old at intake, English-speaking, and pregnant or within 6 months postpartum. Exclusion criteria included a history of or current schizophrenia or bipolar disorder or alcohol or drug abuse.

Mothers’ sociodemographic characteristics varied in the current study with 137 (69%) mothers having a childhood maltreatment history. At intake, mothers’ average age was 28.88 years (SD=5.66; range = 18– 45), and 14.69% had achieved a high school-level education or less, 23.9% were un-partnered, and 19.6% had an annual income below the federal poverty line. Mothers also varied in race/ethnicity: 59% were Caucasian, 22% African American, and 13% were from another ethnic minority group. All infants were born full-term and without developmental or medical problems. The 192 participants who completed the 6-month home visit differed significantly from the 76 non-participants from the larger sample (N=268) on income (participants > non-participants) and race (participants were more likely to be White than non-participants). There were no differences on maternal age, education, or infant sex. Reasons for drop-out included could not be contacted (86%), not interested (12%), or moved away (4%).

Procedure

All procedures were IRB-approved. The present study used data from the 6-month home visit. At this visit, mothers provided written consent, completed interviews and questionnaires, and underwent the interactive tasks, which were video-taped for later coding.

Measures

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; 27) was used to evaluate maltreatment severity. This 28-item measure was administered at the 4 month phone interview using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true; range from 5–140) with higher total scores indicating greater severity of mothers’ childhood trauma exposure.

The Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PPDS; 28) total score was used to assess mothers’ current level of depressive symptoms (α= .96). Though we use the total symptom score in the present study, it should be noted that 17% of women exceeded the clinical cut-off score of 80 or higher [28].

The National Women’s Study PTSD Module (NWS-PTSD; 29) total symptom score was used to assess mothers’ level of current PTSD symptoms (α=.85). Though we use the total symptom score in the present study, it should be noted that 22% of women exceeded the clinical criteria for PTSD. Of note, PTSD was measured according to DSM-IV [30] criteria using data gathered via the civilian version of the NWS-PTSD module [29]. The NWS-PTSD module has been validated against a gold standard semi-structured diagnostic interview (SCID) and shown to have good sensitivity (0.99) and specificity (0.79) to detect PTSD diagnosis (29). The correlation between depressive symptoms and PTSD symptoms in the present study (r = .57) is similar to that found in other studies with consistent with other research that focuses on postpartum symptomology in women with trauma histories (e.g., r =.80, r = .57; 31,32).

Observed Maternal and Infant Affective Displays

Mother-infant dyads were videotaped during two contrasting social interaction tasks: a 10-minute free play and the Still-Face paradigm. During the free play, mothers played with their infants as they usually would do using a standard set of toys provided by the research team. Afterwards the dyad underwent the Still-Face Paradigm (SFP, 20), a structured interactive task consisting of three successive 2-minute episodes: “normal” play (baseline play), a maternal still-face, and a reengagement period (see 22 for complete description). During the still-face episode, infants typically exhibit an increase in negative affect and a decrease in positive affect, whereas during the reunion, infants demonstrate a carryover of negative affect and a rebound of positive affect [23].

Videotaped interactions were independently coded for maternal and infant positive and negative affect using 5-point Likert ratings from the MACY Infant-Parent Coding System [22,31, 3]. For each code, there was a possible range from 1–5 with 1 indicating no affect of a given valence (positive or negative) and 5 indicating high levels of affect (positive or negative). All codes include vocal, facial, and behavioral indices of affect. Positive affect codes were on a graduated scale from no positive affect (1), some positive affect (2), to enthusiasm (3), to much enthusiasm/joy (5). Each end refers to the degree and intensity of the individual’s pleasure and enjoyment of the interaction as indicated by things such as smiling, laughing, clapping, and/or positive vocal tone. Negative affect codes were on a graduated scale from neither flat nor negative affect (1) to much negative affect (5). The points of the scale differentiate sad, wistful, or blank gazing facial responses, and flat, monotone, slowed, and/or mechanical types of vocal expression and speech.

For scoring purposes, the 10-minute free play context was divided into two 5-minute intervals (free play 1 and free play 2). The two free play contexts and the baseline SFP play and SFP reunion were each coded separately, resulting in four positive affect and four negative affect scores for each mother and infant. The still-face episode of the SFP was not scored due to constraints on maternal affect. All coders were masked to maternal trauma severity, psychopathology, and the study’s hypotheses. Inter-coder reliability was excellent (see Table 1) as assessed via intraclass correlations (ICC) of 40 randomly chosen double-coded dyads. Further, correlations in this study (see Table 1) and other studies using these codes (see 22,34) indicate that the codes relate to other variables in the expected direction.

Table 1.

Correlations between primary study variables and Means, Standard Devaitions (SD), and Interclass Correlations (ICC) for Maternal and Infant Affect.

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ICC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maltreatment Severity | 43.740 (18.031) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. 6 Month Postpartum Depression Symptoms | 63.321 (22.351) | .376** | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3. 6 Month Postpartum PTSD Symptoms | 4.337 (4.459) | .517** | .565** | |||||||||||||||||

| Maternal Positive Affect | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Baseline Play | 2.539 (0.625) | .100 | −.163* | .012 | 0.921 | |||||||||||||||

| 5. Free Play 2 | 2.494 (0.645) | .168* | −.164* | .045 | .789** | 0.916 | ||||||||||||||

| 6. Free Play SFP | 2.946 (0.707) | .112 | .019 | .021 | .290** | .347** | 0.857 | |||||||||||||

| 7. Reunion SFP | 2.782 (0.769) | .085 | −.013 | .031 | .315** | .402** | .659** | 0.796 | ||||||||||||

| Infant Positive Affect | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Baseline Play | 1.583 (0.710) | −.009 | .037 | −.079 | .209** | .168* | .077 | .141 | 0.902 | |||||||||||

| 9. Free Play 2 | 1.613 (0.705) | .049 | .126 | .117 | .094 | .149* | .091 | .138 | .594** | 0.870 | ||||||||||

| 10. Free Play SFP | 2.326 (0.902) | .102 | .149 | .124 | .013 | .067 | .486** | .421** | .202** | .224** | 0.927 | |||||||||

| 11. Reunion SFP | 2.087 (0.864) | −.009 | .063 | .065 | .093 | .141 | .334** | .608** | .171* | .216** | .558** | 0.950 | ||||||||

| Maternal Negative Affect | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Baseline Play | 1.124 (0.434) | −.085 | .017 | −.182* | −.340** | −.346** | −.113 | −.172* | −.065 | −.069 | −.091 | −.157* | 0.957 | |||||||

| 13. Free Play 2 | 1.163 (0.514) | −.027 | .066 | −.155 | −.278** | −.312** | −.078 | −.103 | −.033 | −.016 | −.028 | −.067 | .868** | 0.882 | ||||||

| 14. Free Play SFP | 1.060 (0.238) | −.147 | .054 | −.113 | −.255** | −.289** | −.151* | −.162* | −.017 | −.010 | −.085 | −.164* | .642** | .624** | 0.814 | |||||

| 15. Reunion SFP | 1.076 (0.346) | −.103 | .093 | .048 | −.217** | −.208** | −.113 | −.196* | .001 | .082 | −.060 | −.178* | .146 | .099 | .541** | 0.793 | ||||

| Infant Negative Affect | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. Baseline Play | 1.160 (0.417) | .096 | −.078 | −.102 | .040 | .117 | .136 | .066 | −.068 | .004 | .048 | −.012 | −.049 | −.080 | −.037 | −.029 | 0.920 | |||

| 17. Free Play 2 | 1.219 (0.475) | .046 | −.108 | −.105 | −.005 | −.002 | .018 | −.051 | −.086 | −.124 | −.111 | −.113 | .022 | −.046 | −.076 | −.073 | .602** | 0.929 | ||

| 18. Free Play SFP | 1.772 (1.002) | −.125 | −.086 | .016 | .085 | −.031 | −.226** | −.235** | .080 | .079 | −.369** | −.372** | .015 | −.050 | .006 | .047 | .045 | .141 | 0.971 | |

| 19. Reunion SFP | 2.474 (1.282) | −.079 | −.043 | −.047 | −.079 | −.107 | −.220** | −.399** | −.111 | .021 | −.343** | −.528** | .086 | .063 | .104 | .176* | .065 | .097 | .532** | 0.968 |

Note.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

SFP = Still Face Paradigm.

Data Analysis

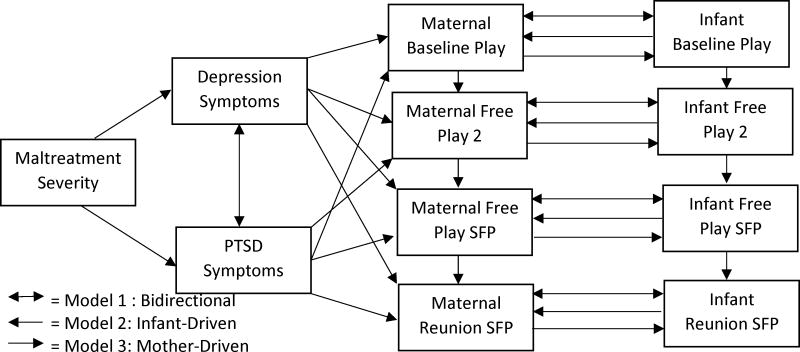

Univariate and bivariate statistics were completed first on the study variables (see Table 1). Given our interest in examining whether mother-infant affective exchanges were bidirectional in nature, or whether they were driven by infant or mother, we compared six path models (three for positive affect and three for negative affect) using M Plus v.7.11, with the Maximum Likelihood estimation method (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2014). Three models were run: Model 1 tells us the bidirectional relationship between maternal and infant affect. The direct pathways are designated as follows: 1) The relationship between maternal maltreatment severity, and PTSD and Depression symptoms; 2) The relationship between maternal PTSD and Depression symptoms; 3) The relationship between maternal Depression symptoms and maternal affect (at all time points) while controlling for PTSD symptoms; 4) The relationships between maternal PTSD symptoms and maternal affect (at all time points) while controlling for Depression symptoms; 5) The relationship between maternal and infant affect and the directionality of the relationship (influences each other/bidirectional). Model 2 tells us the relationship of variables in an infant driven model: pathways 1) to 4) are the same as in Model 1 and 5) the relationship between maternal and infant affect and the directionality of the relationship (infant predicting mother). Model 3 tells us the relationships in the maternal driven model: pathways 1) to 4) Are the same as Model 1; and 5) the relationship between maternal and infant affect and the directionality of the relationship (mother predicting infant). Models 1–3 were run separately for positive and for negative affect (see Figure 1). Nonhierarchical model comparison (35) was used to identify the model that best represented the data. Model fit was assessed using the root mean square error of approximation with 90% confidence intervals (RMSEA; < .08 reasonable fit), comparative fit indices (CFI; >.95 good fit), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; <.10 favorable, 31)). If multiple models were determined to have adequate fit based on aforementioned criteria, then model comparisons were conducted using the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC (31)). Finally, multiple imputation with five data sets was used and is an appropriate estimation procedure for missing data [36].

Figure 1.

Proposed Path Analytic Models of Relationships between Maternal and Infant Positive and Negative Affective Displays.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

All variables were screened for normality, outliers, and multi-collinearity; however, Kline (2011; 31) indicates that estimation models in path analyses are robust. Examination of bivariate correlations indicates varying associations between maltreatment severity, depression and PTSD symptoms, and maternal and infant positive and negative affect during each segment (see Table 1 for associations).

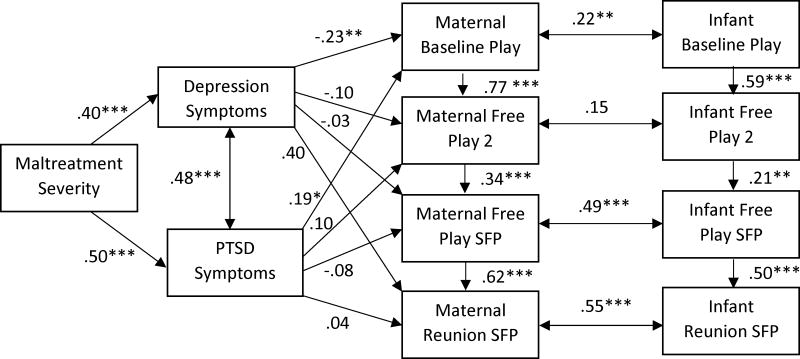

Positive Affect

Statistics for the positive affect path models are displayed in Table 2. Model 1 (bidirectional) and Model 2 (infant-driven) each had a good fit, but Model 3 (mother-driven) did not. Results of model comparisons indicated that Model 1 had the best fit and was thus selected. Model 1 results (displayed in Figure 2) show that childhood maltreatment severity was positively associated with maternal PTSD and depression symptoms, and that PTSD and depressive symptoms were significantly positively related. In turn, both PTSD and depression predicted mothers’ positive affect during the baseline free play episode, yet in opposite directions (depression was negatively related and PTSD positively). Across all other episodes, maternal symptomology was unrelated to her positive affect. Finally, maternal and infant positive affect was significantly, positively correlated across all episodes except the 2nd free play; magnitude of association is modest (r=.22) during baseline free play, higher during baseline play of the SFP (r=.49), and strongest during reunion (r=.55; see Figure 2). In sum, the interactions between mother and infant are bidirectional and increasing in magnitude across the tasks, with depression and PTSD differentially predicting maternal positive affect during the initial play session. Moreover, childhood maltreatment severity predicted both depression and PTSD symptoms.

Table 2.

Model Fit Indices for the Relationships between Maternal and Infant Positive and Negative Affect (n=192)

| χ2(df) | RMSEA | RMSEA 90% CI | CFI | SRMR | AIC | BIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Model 1+ | 57.97 (34)*** | 0.06 | .03–.09 | 0.96 | 0.07 | 5583.12 | 5716.74 |

| Model 2 | 55.82 (34)** | 0.06 | .03–.08 | 0.97 | 0.07 | 7243.76 | 7383.83 |

| Model 3 | 75.11 (34)*** | 0.08 | .06–.10 | 0.94 | 0.07 | 5603.19 | 5736.75 |

|

| |||||||

| Negative Affect | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Model 1+ | 51.88 (34)* | 0.05 | .02–.08 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 4490.52 | 4624.07 |

| Model 2 | 52.79 (34)* | 0.05 | .02–.08 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 6153.92 | 6293.99 |

| Model 3 | 54.69 (34)* | 0.06 | .03–.08 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 4493.86 | 4627.42 |

Note.

p<.05.

p <.01,

p< .00.

Best Fitting Model. Model 1 = Bidirectional, Model 2 = Infant-Driven, Model 3= Mother-Driven

Figure 2.

Final Best Fit Path Analytic Model Examining the Relationships between Maltreatment Severity, Depression, PTSD, and Maternal and Infant Positive Affect. Standardized Coefficients are Shown. p<.05*. p <.01**, p< .00***

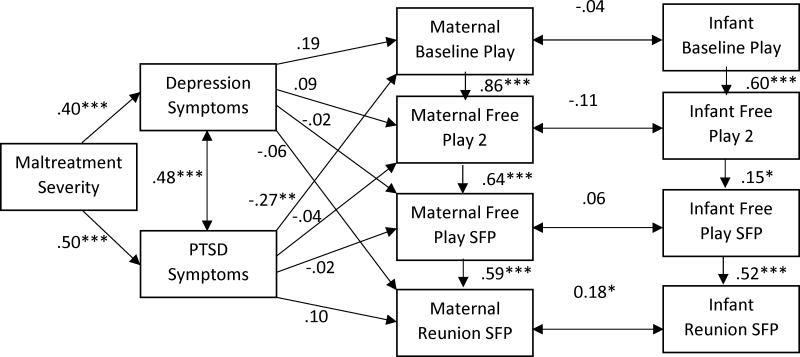

Negative Affect

Models 1, 2, and 3 each had a good fit to the data (see Table 2); however, based on model comparison indices, Model 1 was the best fitting model. Model 1 resembles prior described associations for positive affect between maltreatment severity, PTSD, and depression. Maternal symptomology was unrelated to negative affect across all episodes, with the exception of maternal PTSD symptoms which were negatively related to maternal negative affect during the baseline free play episode. Maternal and infant negative affect were only related during the reunion episode (r=.18). In sum, the interactions between mother and infant were bidirectional, however, only PTSD predicted maternal negative affect and maternal infant affect varied by task.

It is notable that in all models, the Chi-square indices were significant, which suggests the model does not reproduce the data. However, according to Kline (2011) the chi-square indices are fundamentally flawed and the model may not capture the information in the implied correlations. Thus, McDonald and Ho (2002) recommend examining the model implied correlations or standardized residuals to more accurately understand the model fit. A suggested cut-off of 1.96 was used to determine the number of residuals that were beyond the critical value. In Model 1 positive affect, seven out of sixty-six residuals were above the threshold suggesting the model is a good fitting model. The same process was completed for Model 1 of negative affect which identified two of sixty-six residuals above the threshold; again suggesting a good fitting model.

Additionally, the above analyses were run with the 137 participants that endorsed a history of childhood maltreatment (and excluded the 55 participants who did not experience maltreatment during childhood) and similar results were obtained; therefore, the sample including all 192 participants was retained for greater power.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the dyadic bidirectional exchange of observed maternal and infant positive and negative emotional displays across two social interaction tasks in mothers accounting for maternal childhood maltreatment severity, and symptoms of postpartum psychopathology. Overall, we found support that affective exchanges between mothers and their 6-month old infant are bidirectional; that is, maternal and infant affective influences are reciprocal and the strength of this bidirectional relationship varies by task and the emotional valence. Overall, mother-infant bidirectional associations were stronger for positive affect, and present across both low stress and high stress interactive exchanges, with strongest association during the reunion episode after the still-face. By contrast, bidirectional association for negative affect held up only for the high stress task, the reunion episode.

Our bidirectional findings are consistent with the Mutual Regulation Model that suggests that more dyadic affective coordination (coordination in our study was reflected by strength of relation between mother-infant same valence affect) contributes to more interactive positive affect [1]. There were fewer significant relations between mother-infant negative affect compared to positive affect. Of note, mean levels of negative affect were lower than positive so it may have also been the case that low levels of negative affect were less “contagious.” In contrast, when negative affect is high, such as in the SFP reunion, “mirroring” occurs for both dyadic partners. From an evolutionary perspective, warmth in parent-child relationships promotes relational cohesion and motivates behavior through creating an intrinsically rewarding affective system [37] –perhaps suggesting an evolutionary advantage of “contagious” positive affect. In support of this assumption is prior work demonstrating that greater positive affect in infancy is linked with better emotional and behavioral outcomes two years later [6], and that greater positive versus negative infant affect in the SFP is linked with better child regulation [5]. Furthermore, the pattern of greatest affective synchrony following high stress exposure (i.e., the maternal still-face) indicates that more stress may increase reciprocal dyadic coordination wherein mother and infant’s reactions shape the responsiveness of the other. This finding is also consistent with past research showing that maternal and infant behavior during stressful tasks tends to have greater variability and stressful tasks may pull for more negative parenting behaviors compared to benign tasks [24]. Thus, our findings confirm prior research on mother- infant mutual co-regulation of emotional displays [1,16], with strongest co-regulation following high stress [38].

Our work extends prior reports by examining this dyadic emotional co-regulation in a sample of at-risk mothers based on their childhood maltreatment severity and/or their concurrent symptoms of postpartum psychopathology. We found, that depression and PTSD symptoms differentially impacted mother affective displays. As expected and consistent with others [16], depressive symptoms predicted lower maternal positive affect, but contrary to our expectations, PTSD symptoms predicted lower maternal negative affect and higher maternal positive affect. Finally, maltreatment severity predicted concurrent depression and PTSD symptoms.

Our results offer a message of risk as well as resilience. The findings suggestive of resilience are that maltreatment severity predicted postpartum PTSD symptoms and PTSD symptoms were related to more adaptive maternal affective displays in the initial interactions (i.e., lower negative/higher positive affect). This finding may initially seem counterintuitive, yet may reflect the nature of PTSD vs. depression symptoms. Specifically, by definition, depression involves relatively stable depressed mood across time whereas PTSD symptoms may be prone to wax and wane based on context and trauma triggers. Perhaps our interactive tasks may not have been perceived as too threatening and thus deleterious PTSD symptoms such as dissociation and anger may not have been activated during the interactions. Assuming our task was not triggering, then it may have been that PTSD symptoms were not activated and therefore did not interfere with “positive” parenting. Regarding the positive association between PTSD symptoms and maternal positive affect, it may be that hyperarousal and anxiety associated with PTSD make mothers more sensitive to the social desirability effect, and thus they worked harder than other mothers to “appear” happy, thus showing elevated levels of positive affect. Conversely, anecdotally based on clinical experience mothers with trauma histories share their wish to provide a better childhood for their babies than the childhood they experienced, suggesting that trauma survivor mothers may intentionally exaggerate positive affect in an attempt to create a warm and nurturing experience for their babies. The limited research in this arena highlights the importance of further work on posttraumatic growth (i.e., positive change experienced as the result of surviving something traumatic) in trauma survivor mothers and how this may impact parenting behaviors. We believe our findings suggest that PTSD symptoms do not “doom” one to negative parenting practices and view this as an important area for future research. Our results are strengthened by the fact that we accounted for symptom comorbidity which allowed us to test PTSD’s predictions to maternal affect, even after controlling for maternal depression.

Our study is not without limitations. While our results are strengthened by the use of observational paradigms, future research would benefit from adding psychophysiological assessment to provide a more comprehensive picture of emotional reactivity in mother and child. Similarly, future studies would also benefit from a replication with a larger data set to be able to model the impact of various moderators (including diagnoses of depression, PTSD, comorbidity, or no diagnoses; and mothers with and without childhood maltreatment; infant temperament) on the described effects. Further, although we used standardized and validated diagnostic tools, we acknowledge limitations of relying solely on maternal report of symptoms rather than clinician-made diagnoses. Lastly, the path analyses had significant chi-squares which suggest sources of misfit and that the models were not perfect; however, to more accurately understand the sources of misfit, we examined residuals as proposed by scholars in this field and found adequate model fit. Future analyses utilizing a larger sample size may additionally address such sources of misfit.

This study has translational relevance as it provides empirical support for bi-directionality in emotional displays as early as 6 months even among mother-infant dyads where the mothers suffer depression and/or PTSD symptoms. Our findings highlight the need for screening of postpartum symptoms, particularly among women with maltreatment histories. Furthermore, we deliver a message of hope, suggesting that childhood maltreatment severity or the presence of PTSD symptoms do not automatically lead to negative affective exchanges between a mother and her infant. Clinically, our results substantiate mothers’ and clinicians’ observations that dyadic affect is a two-way street—both mother and baby are active agents in that process. We believe our findings validate and empower mothers, especially those working hard to overcome the hardships of childhood maltreatment and postpartum psychopathology.

Figure 3.

Final Best Fit Path Analytic Model Examining the Relationships between Maltreatment Severity, Depression, PTSD, and Maternal and Infant Negative Affect. Standardized Coefficients are Shown. p<.05*. p <.01**, p< .00***

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted at the University of Michigan supported by the National Institute of Health-Michigan Mentored Clinical Scholars Program awarded to M Muzik (K12 RR017607-04, PI: D. Schteingart); the National Institute of Mental Health -Career Development Award K23 (NIH, PI: Muzik); and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (MICHR, UL1TR000433, PI: Muzik).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Tronick EZ. Emotions and emotional communication in infants. Am Psychol. 1989 Feb;44(2):112–9. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campos JJ, Campos RG, Barrett KC. Emergent themes in the study of emotional development and emotion regulation. Dev Psychol. 1989 May;25(3):394–402. [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacLean PC, Rynes KN, Aragón C, Caprihan A, Phillips JP, Lowe JR. Mother–infant mutual eye gaze supports emotion regulation in infancy during the Still-Face paradigm. Infant Behav Dev. 2014 Nov;37(4):512–22. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman R. Parent-infant synchrony: Biological foundations and developmental outcomes. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007 Dec;16(6):340–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braungart-Rieker JM, Garwood MM, Powers BP, Wang X. Parental Sensitivity, Infant Affect, and Affect Regulation: Predictors of Later Attachment. Child Dev. 2001;72(1):252–70. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mäntymaa M, Puura K, Luoma I, Latva R, Salmelin RK, Tamminen T. Shared pleasure in early mother–infant interaction: Predicting lower levels of emotional and behavioral problems in the child and protecting against the influence of parental psychopathology. Infant Ment Health J. 2015 Mar;36(2):223–37. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross LE, McLean LM. Anxiety Disorders During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: A Systematic Review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 Aug;67(8):1285–98. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Studd J, Nappi RE. Reproductive depression. Gynecol Endocrinol Off J Int Soc Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012 Mar;28(Suppl 1):42–5. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.651932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seng JS, Low LK, Sperlich M, Ronis DL, Liberzon I. Prevalence, trauma history, and risk for posttraumatic stress disorder among nulliparous women in maternity care. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Oct;114(4):839–47. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b8f8a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: Results from the Adverse Childhood Experiences study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Aug;160(8):1453–60. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koenen KC, Widom CS. A prospective study of sex differences in the lifetime risk of posttraumatic stress disorder among abused and neglected children grown up. J Trauma Stress. 2009 Dec;22(6):566–74. doi: 10.1002/jts.20478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muzik M, McGinnis EW, Bocknek E, Morelen D, Rosenblum KL, Liberzon I, et al. Ptsd Symptoms Across Pregnancy and Early Postpartum Among Women with Lifetime Ptsd Diagnosis. Depress Anxiety. 2016 Jan 1; doi: 10.1002/da.22465. n/a–n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal Depression and Child Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011 Mar 4;14(1):1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowers ME, Yehuda R. Intergenerational Transmission of Stress in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016 Jan;41(1):232–44. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorce JF, Emde RN, Campos JJ, Klinnert MD. Maternal emotional signaling: Its effect on the visual cliff behavior of 1-year-olds. Dev Psychol. 1985 Jan;21(1):195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman R. Infant-mother and infant-father synchrony: The coregulation of positive arousal. Infant Ment Health J. 2003 Jan;24(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schore AN. Effects of a secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Ment Health J. 2001 Jan;22(1–2):7–66. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enlow MB, Kitts RL, Blood E, Bizarro A, Hofmeister M, Wright RJ. Maternal posttraumatic stress symptoms and infant emotional reactivity and emotion regulation. Infant Behav Dev. 2011 Dec;34(4):487–503. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forbes EE, Cohn JF, Allen NB, Lewinsohn PM. Infant Affect During Parent-Infant Interaction at 3 and 6 Months: Differences Between Mothers and Fathers and Influence of Parent History of Depression. Infancy. 2004 Feb;5(1):61–84. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in0501_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tronick E, Als H, Adamson L, Wise S, Brazelton TB. The Infant’s Response to Entrapment between Contradictory Messages in Face-to-Face Interaction. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1978 Dec 1;17(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)62273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Feijo L, Vera Y, Gil K, et al. Still-face and separation effects on depressed mother-infant interactions. Infant Ment Health J. 2007 May;28(3):314–23. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Torteya C, Dayton CJ, Beeghly M, Seng JS, McGinnis E, Broderick A, et al. Maternal parenting predicts infant biobehavioral regulation among women with a history of childhood maltreatment. Dev Psychopathol. 2014 May;26(2):379–92. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mesman J, van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. The many faces of the Still-Face Paradigm: A review and meta-analysis. Dev Rev. 2009 Jun;29(2):120–62. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller AL, McDonough SC, Rosenblum KL, Sameroff AJ. Emotion Regulation in Context: Situational Effects on Infant and Caregiver Behavior. Infancy. 2002 Oct 1;3(4):403–33. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000 Aug;20(5):561–92. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seng JS, Low LK, Sperlich M, Ronis DL, Liberzon I. Prevalence, trauma history, and risk for posttraumatic stress disorder among nulliparous women in maternity care. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Oct;114(4):839–47. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b8f8a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood trauma questionnaire: a retrospective self-report : manual. Orlando: Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck CT, Gable RK. Postpartum Depression Screening Scale: Development and psychometric testing. Nurs Res. 2000 Sep;49(5):272–82. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200009000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(6):984–91. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schechter DS, Suardi F, Manini A, Cordero MI, Rossignol AS, Merminod G, et al. How do maternal PTSD and alexithymia interact to impact maternal behavior? Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2015 Jun;46(3):406–17. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schechter DS, Willheim E, Hinojosa C, Scholfield-Kleinman K, Turner JB, McCaw J, et al. Subjective and objective measures of parent-child relationship dysfunction, child separation distress, and joint attention. Psychiatry Interpers Biol Process. 2010 Sum;73(2):130–44. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2010.73.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Earls L, Muzik M, Beeghly M. Maternal and Infant Behavior Coding Manual. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muzik M, Bocknek EL, Broderick A, Richardson P, Rosenblum KL, Thelen K, et al. Mother–infant bonding impairment across the first 6 months postpartum: The primacy of psychopathology in women with childhood abuse and neglect histories. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013 Feb;16(1):29–38. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0312-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2011. (Methodology in the Social Sciences) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newman DA. Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: A simulation of ad hoc, maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation techniques. Organ Res Methods. 2003 Jul;6(3):328–62. [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacDonald K. Warmth as a Developmental Construct: An Evolutionary Analysis. Child Dev. 1992 Aug 1;63(4):753–73. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hibel LC, Granger DA, Blair C, Cox MJ. Intimate partner violence moderates the association between mother–infant adrenocortical activity across an emotional challenge. J Fam Psychol. 2009;23(5):615–25. doi: 10.1037/a0016323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]