Abstract

Background

The burden of venous thromboembolism (VTE) related to permanent work-related disability has never been assessed among a general population. Therefore, we aimed to estimate the risk of work-related disability in subjects with incident VTE compared with those without VTE in a population-based cohort.

Methods

From the Tromsø Study and the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT), Norway, 66005 individuals aged 20–65 years were enrolled in 1994–1997 and followed to December 31, 2008. Incident VTE events among the study participants were identified and validated, and information on work-related disability was obtained from the Norwegian National Insurance Administration database. Cox-regression models using age as time-scale and VTE as time-varying exposure were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) adjusted for sex, BMI, smoking, education level, marital status, history of cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and self-rated general health.

Results

During follow-up, 384 subjects had a first VTE and 9862 participants were granted disability pension. The crude incidence rate of work-related disability after VTE was 37.5 (95%CI: 29.7–47.3) per 1000 person-years, versus 13.5 (13.2–13.7) per 1000 person-years among those without VTE. Subjects with unprovoked VTE had a 52% higher risk of work-related disability than those without VTE (HR 1.52, 95%CI 1.09–2.14) after multivariable adjustment, and the association appeared to be driven by deep vein thrombosis.

Conclusion

VTE was associated with subsequent work-related disability in a cohort recruited from the general working-age population. Our findings suggest that indirect costs due to loss of work time may add to the economic burden of VTE.

Keywords: Venous thromboembolism, Deep vein thrombosis, Risk, Disability

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), a general term for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a common disease affecting 1–2 per 1000 persons annually, with an exponential increase in incidence with age from 1 per 10 000 in young adults, to 1 per 100 in the elderly [1,2]. The one-year all-cause mortality after VTE is approximately 10–20% [1,3], and it has been reported, based on autopsy data, that approximately 3–5% of all adult deaths may be due to PE [4]. Survivors of VTE are at risk of long-term complications such as recurrence, post-thrombotic syndrome, and pulmonary hypertension. Non-fatal recurrence affects 10–30% of VTE patients within 5 years, and occurs most often at the same site as the first thrombosis [5,6]. Moreover, unprovoked VTE is associated with higher recurrence risk than provoked VTE [7–9].

Post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) due to impaired venous circulation affects 20–50% of patients with a proximal leg DVT, and usually appears within 1 to 2 years after the thrombotic event [6,10]. The risk of PTS is higher in patients with recurrent episodes of DVT [11]. PTS causes chronic limb fatigue or heaviness, swelling, pain, and paraesthesia. The most severe complication of PTS is open venous leg ulcers, which occur in 5–10% of survivors of acute proximal lower-extremity DVT [7,9,10,12,13]. In studies of the long-term impact of PTS, symptomatic patients reported significantly reduced physical functioning [14–16], limitations attributed to physical health [17], and impaired quality of life [14–16].

Incomplete thromboembolic resolution after PE may result in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) caused by intraluminal thrombus organization leading to fibrous stenosis or occlusion of affected pulmonary arteries, and remodelling of unaffected small distal pulmonary arteries [18]. Subsequently, these vascular changes may contribute to increased pulmonary vascular resistance and right ventricular afterload [19]. CTEPH occurs in 0.5%–1.5% of PE cases and in 1.5–4.0% of patients with unprovoked PE [20–24], and manifests itself by insidious dyspnoea which severely impair mobility and quality of life [25–26]. The vast majority of CTEPH cases are identified within the first 2 years after the initial PE diagnosis [20–23]. Although CTEPH is rare, a recent study suggested that up to half of patients with PE may develop “post-PE syndrome”, a condition characterized by exercise limitation that influences the degree of dyspnea and quality of life [27].

Even though it is plausible to assume that chronic complications of VTE would affect functional activities and working ability, the long-term impact of VTE on activity limitations or disability has been scarcely investigated. In a case-series of 21 patients with severe iliofemoral DVT, almost all (86%) developed venous leg ulcers and two-thirds were hospitalized on five or more occasions due to complications within 10 years [28]. The investigators reported that 92% of male patients and 78% of female patients experienced work-related disability. However, this was a skewed sample with much greater severity than typical VTE patients [28].

To the best of our knowledge, a population-based study addressing the long-term association between VTE and work-related disability has not been performed. Therefore, we aimed to assess the association between first VTE and subsequent work-related disability, assessed by receipt of disability pension, in a cohort recruited from the general population.

Methods

Subjects were recruited from the second survey of the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT 2) and the fourth survey of the Tromsø study (Tromsø 4), two population-based health surveys of inhabitants in the county of Nord-Trøndelag and the municipality of Tromsø, Norway [29,30]. Tromsø 4 was conducted in 1994–95. All residents aged 25 or older were invited and 27 158 (77% of those invited) participated. HUNT 2 was carried out in 1995–97, and all residents aged 20 or above were invited. Among those who were eligible 66 140 (71 %) attended. For the current study on work-related disability, 72 453 individuals from Tromsø 4 and HUNT 2 that were younger than 65 years at baseline were eligible. Of these, 6404 had already received disability pension, and 44 had received contractual early retirement pension at baseline, and were therefore excluded. Thus, our study comprised 66 005 individuals followed from the date of inclusion (1994–97) until December 31, 2008 (end of follow-up).

In both HUNT 2 and Tromsø 4, baseline variables were collected through physical examinations, blood samples and self-administered questionnaires, as previously described in detail [31,32]. Height and weight were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was expressed as kg/m2. Information on marital status, current smoking, education level and history of diseases was derived from the questionnaire. Education level was divided into two categories, where high education was defined as more than four years at University or University College and low as everything else. History of cardiovascular disease was defined as self-reported history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris or ischemic stroke. Self-rated general health was reported in four categories (poor, not so good, good and very good).

VTE exposure assessment

Both the Tromsø area and the Nord-Trøndelag area are served by a centralized public health service, which makes them well-suited for a population-based study with follow-up. The hospitals are exclusive providers of both in- and outpatient care of VTE, and the hospital registries contain VTE patients derived from both the hospital- and community setting. All incident VTE events during follow-up were identified by searching the hospital discharge diagnosis registries and the radiology procedure registries at Levanger and Namsos Hospital (HUNT2) and the University Hospital of North Norway (Tromsø 4) as previously described [1,33]. Thereafter, the medical record for each potential VTE case was reviewed and validated by trained personnel. A VTE event was recorded when presence of clinical signs and symptoms of DVT or PE were combined with objective confirmation tests (compression ultrasonography, venography, spiral computed tomography, perfusion-ventilation scan, pulmonary angiography, autopsy), and resulted in a VTE diagnosis that required treatment. In addition, in Tromsø, other VTE cases that had not been diagnosed clinically were identified by conducting a search through the autopsy registry; VTE cases were recorded when the death certificate indicated VTE as cause of death or a significant condition associated with death.

The VTEs were classified as PE (i.e. PE with and without concurrent DVT) or DVT (DVT without PE) based on localization of thrombi assessed by radiological procedures. Furthermore, the VTE events were classified as provoked or unprovoked depending on the presence of provoking factors at the time of diagnosis. Provoking factors were recent surgery or trauma (within the previous 8 weeks), acute medical conditions (acute myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke or major infectious disease), active cancer, immobilization (bed rest >3 days, wheelchair use or long-distance travel within the last 14 days) or any other relevant factor specifically described as provoking by a physician in the medical record (e.g. intravascular catheter).

Outcome assessment of work-related disability

Work-related disability was assessed by receipt of disability pension. Information on disability pension was obtained from the Norwegian National Insurance Administration database kept by Statistics Norway. This database contains complete information on all disability pensions granted in Norway, date of granting, and has well-established criteria for eligibility for granting disability pension. Because the pensions cover the entire population, the benefits are in practice utilized by all residents. The disability data was linked to the Tromsø 4 and HUNT 2 participants based on the unique Norwegian 11-digit personal identification number.

The disability pension system in Norway was written into law in 1967. According to the law, a person is eligible to apply for a disability pension if he/she is between the ages of 16 and 67, has been a member of the national insurance program for at least 3 years and met the following medical criteria: 1) earning ability was permanently impaired by at least 50% due to illness, disease, injury or disability; 2) the illness, disease, injury or disability must have been the main cause of impaired earning ability; and 3) the applicant had undergone appropriate medical treatment and rehabilitation in order to improve earning ability. The disability pension lasts until the retirement pension begins at age 67 or death, whichever comes sooner. In our study, a grant of disability pension (outcome) was defined from the date a participant received a disability pension of at least 50%. It should be noted that receipt of a disability pension is a relatively stringent measure of disability. Disability does not necessarily affect earnings and may not be permanent. Therefore, this measure understates the actual prevalence of disability.

Statistical analyses

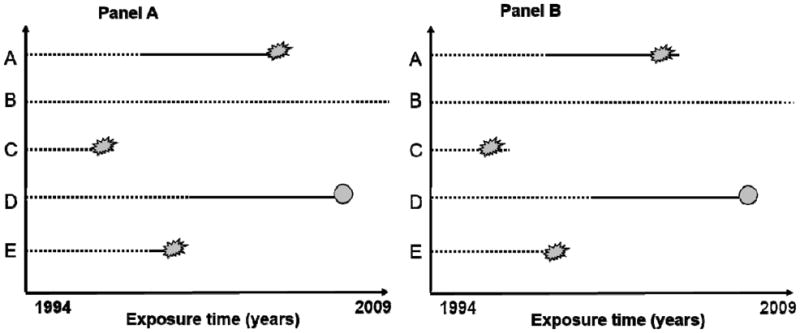

Subjects who developed VTE during the study period contributed non-exposed person time from the baseline inclusion date to the date of a diagnosis of VTE, and then exposed person time from the date of VTE onwards (Figure 1). For each participant, non-exposed and exposed person-years were counted from the date of enrolment (1994–97) to the date of disability pension, the date of contractual early retirement, the 67th birthday, date of migration, date of death, or until the end of the study period (December 31, 2008), whichever came first. Subjects who received contractual early retirement, turned 67, moved or died during follow-up were censored from the corresponding date of occurrence.

Figure 1. Graphical Illustration of time-varying exposure in the study.

Panel A: Time-varying model where outcome was assessed at the official date of disability pension. Subject A starts without venous thromboembolism (VTE), develops VTE during follow-up and receives subsequent disability pension. Subject B has no VTE during the entire study period, and contributes 15 years of non-exposed person time. Subject C has no VTE but receives disability pension. Subject D develops VTE during follow-up and dies before study end. Subject E develops VTE and receives disability pension within one year after the VTE.

Panel B: Time-varying model where outcome was assessed one year before the official date of disability pension. Subjects had to be on sick leave for at least one year before they could apply for disability pension. Therefore, subjects were likely to be disabled already one year before the disability pension was granted, and those who received disability pension within one year after the VTE were likely to be granted disability pension for reasons other than the VTE. By modelling the outcome date one year before the official disability date, the time-to-event was shortened by one year and subjects who were granted disability within one year after the VTE would be classified as non-exposed in this model (e.g. subject E).

Statistical analyses were performed with STATA version 13.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Crude incidence rates (IR) were expressed as number of events per 1000 person-years at risk. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to obtain crude and multivariable hazard ratios (HR) of work-related disability with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Age was used as time-scale and the subjects’ age at study enrolment was defined as entry-time, and exit-time was defined as age at disability, contractual early retirement, death, migration, age 67, or age at study end. The exposure variable VTE was entered as a time-varying variable using multiple observation periods per subject (i.e. no subject was registered with VTE at baseline, but the variable was updated for those who developed VTE during follow-up). The multivariable HRs were adjusted for potential confounders as assessed at study entry using four different models. Model 1 included age and sex; Model 2 included age, sex, BMI, smoking, education level and marital status; Model 3 included age, sex, BMI, smoking, education level, marital status, history of cancer, cardiovascular disease and diabetes; Model 4 included all variables from Model 3 + self-rated general health. In addition, subgroup analyses of pulmonary embolism and DVT, as well as unprovoked and provoked VTE, as exposure variables were performed. The proportional hazard assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals. Statistical interaction between VTE exposure and sex was tested by including cross-product terms in the proportional hazard model, and no statistical interaction was found.

In Norway, a person who has been occupied with paid work must have been on sick leave at least one year and tried out appropriate medical interventions as well as work-related adjustments in order to become eligible for a disability pension. This means that work-related disability in most cases actually occurs one year before the official date of granted disability pension. Thus, in subjects where the VTE exposure occurred less than one year before disability pension, the VTE itself would not likely be the main cause of the disability (but rather a consequence of another serious underlying disease that led to the disability pension). In order to avoid this potential bias (i.e. to investigate whether VTE in itself could be causally related to work-related disability), we set the follow-up time of disability to the date one year before the disability pension was granted (Figure 1) and repeated all analyses.

Results

The mean age at inclusion was 41.3 (SD: 11.2) years and 51.2% (n=33 901) were women. During a median of 12.3 years of follow-up, 384 subjects without a history of disability pension had a VTE event. In total, 9862 (14.9%) participants were granted disability pension during follow-up. Baseline characteristics by VTE exposure during follow-up are shown in Table 1. VTE patients were slightly older, had higher BMI, and had a higher proportion of subjects with a history of cancer (4.7% vs. 1.9%) and cardiovascular disease (3.9% vs. 1.8%). Moreover, a higher proportion of VTE patients had paid work compared to those without VTE (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of subjects who did and did not develop venous thromboembolism (VTE) during follow-up. Values are means ± standard deviations in brackets or numbers with percentages in brackets.

| No VTE (n=65621) | VTE (n=384) | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Age (years) | 41.3±11.2 | 45.1± 9.8 |

| Sex (% women) | 33721 (51.4) | 180 (46.9) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.6± 3.9 | 26.9± 4.3 |

| Smoking | 22087 (33.7) | 131 (34.1) |

| High education | 18527 (28.8) | 108 (28.1) |

| Married | 42686 (65.0) | 263 (68.5) |

|

| ||

| History of diseases | ||

|

| ||

| Cancer | 1216 (1.9) | 18 (4.7) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1171 (1.8) | 15 (3.9) |

| Diabetes | 669 (1.0) | 6 (1.6) |

|

| ||

| Employment status | ||

|

| ||

| Paid work | 43414 (66.2) | 283 (73.7) |

| Housekeeping | 4908 (7.5) | 23 (6.0) |

| Student/military | 3896 (5.9) | 15 (3.9) |

| Unemployed | 3153 (4.8) | 16 (4.2) |

| Missing information | 9357 (14.3) | 45 (11.7) |

VTE-related characteristics of VTE patients who did and did not receive subsequent disability pension are shown in Table 2. Those who received disability pension were slightly older, and a higher proportion of the VTEs were DVTs rather than PEs. Moreover, half of the VTE events were classified as unprovoked (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE) with and without work-related disability. Values are means ± standard deviations in brackets or numbers with percentages in brackets.

| No work-related disability after VTE (n=312) | Work-related disability after VTE (n=72) | Work-related disability after VTE* (n=53) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 50.5±10.2 | 55.5±6.0 | 55.1±6.0 |

| Sex (% men) | 145 (46.5) | 35 (48.6) | 24 (45.3) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 112 (35.9) | 20 (27.8) | 15 (28.3) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 200 (64.1) | 52 (72.2) | 38 (71.7) |

| Unprovoked | 138 (44.2) | 36 (50.0) | 34 (64.0) |

| Provoked | 174 (55.8) | 36 (50.0) | 19 (36.0) |

When the date of disability was set one year before the actual date of disability pension

The mean follow-up time in VTE patients after the VTE event was 5 years (384 VTE patients contributed 1918 VTE exposed person-years), and 72 out of 384 VTE patients (19%) received a disability pension. Among those with VTE the incidence rate of work-related disability was 37.5 (95% CI: 29.7–47.3) per 1000 person-years, whereas the incidence rate among those without VTE was 13.5 (95% CI: 13.2–13.7) per 1000 person-years (Table 3). In the age- and sex adjusted model, subjects with VTE had 62% higher risk of receiving a subsequent work-related disability compared with subjects without VTE (HR 1.62, 95% CI: 1.29–2.04). This risk estimate was only slightly affected by adjustments for the majority of baseline characteristics (Model 2 HR 1.57, 95% CI: 1.24–1.98) or history of co-morbidities (Model 3 HR 1.44, 95% CI: 1.12–1.85). When adjusted for baseline self-reported health, the estimate was attenuated but still significant (Model 4 HR 1.30 (1.01–1.67).

Table 3.

Incidence rates (IR) per 1000 person-years and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of work-related disability (official date of disability pension) after venous thromboembolism (VTE).

| Person-years | Work-related disability | Crude IR (95% CI) | Model 1 HR (95% CI) | Model 2 HR (95% CI) | Model 3 HR (95% CI) | Model 4 HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venous thromboembolism (VTE ) | |||||||

| No VTE | 711337 | 9610 | 13.5 (13.2–13.7) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| VTE | 1918 | 72 | 37.5 (29.7–47.3) | 1.62 (1.29–2.04) | 1.57 (1.24–1.98) | 1.44 (1.12–1.85) | 1.30 (1.01–1.67) |

|

| |||||||

| Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No DVT | 712028 | 9630 | 13.5 (13.2–13.8) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| DVT | 1227 | 52 | 42.4 (32.3–55.6) | 1.80 (1.37–2.36) | 1.77 (1.35–2.33) | 1.66 (1.23–2.23) | 1.44 (1.07–1.94) |

|

| |||||||

| Pulmonary embolism (PE) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No PE | 712565 | 9662 | 13.6 (13.3–13.8) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| PE | 691 | 20 | 28.9 (18.7–44.9) | 1.28 (0.83–1.99) | 1.19 (0.76–1.87) | 1.06 (0.66–1.72) | 1.04 (0.64–1.67) |

|

| |||||||

| Unprovoked VTE | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No unprovoked VTE | 712321 | 9646 | 13.5 (13.3–13.8) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Unprovoked VTE | 935 | 36 | 38.5 (27.8–53.4) | 1.52 (1.09–2.11) | 1.48 (1.06–2.07) | 1.40 (0.97–2.02) | 1.34 (0.93–1.94) |

|

| |||||||

| Provoked VTE | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No provoked VTE | 712272 | 9646 | 13.5 (13.3–13.8) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Provoked VTE | 983 | 36 | 36.6 (26.4–50.7) | 1.73(1.25–2.40) | 1.66 (1.19–2.30) | 1.47 (1.04–2.08) | 1.26 (0.89–1.78) |

Model 1: Adjusted for age and sex

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking, education level and marital status

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking, education level, marital status, history of cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease

Model 4: Model 3 + self-rated general health

In subgroup analyses of DVT and PE, patients with DVT had 80% higher risk of work-related disability than those without DVT (Model 1 HR 1.80, 95% CI: 1.37–2.63), whereas only a moderately increased non-significant association was found in patients with PE (Model 1 HR 1.28, 95% CI: 0.83–1.99). When adjusted for baseline characteristics other than self-rated health, the association with DVT remained strong (Model 3 HR 1.66 (1.23–2.23) whereas there was no association with PE (Model 3 HR 1.06 (0.66–1.72). The risk estimates of work-related disability were essentially similar in analyses of unprovoked and provoked VTE (Table 3).

Table 4 shows the incidence rates and hazard ratios for work-related disability when the date of disability was set to one year before the official disability grant date. In these analyses, subjects with VTE had a 37% higher risk of work-related disability than those without VTE (Model 1 HR 1.37, 95% CI 1.05–1.80). Adjustments for other baseline risk factors and co-morbidities attenuated the risk estimate (Model 3 HR 1.26, 95% CI: 0.96–1.65), and the risk was further attenuated after adjustment for self-rated general health (Model 4 HR: 1.17, 95% CI: 0.89–1.53). The risk of work-related disability after a DVT was 53% higher than in those without DVT (Model 1 HR 1.53, 95% CI: 1.11–2.11), whereas no association was found between pulmonary embolism and subsequent risk of work-related disability (HR 1.08, 95%CI: 0.65–1.79). Results were essentially the same when adjusted for baseline characteristics other than self-rated health, both for DVT (Model 3 HR 1.46, 95% CI: 1.06–2.01) and PE (Model 3 HR 0.93, 95% CI: 0.56–1.54). When adjusted for baseline self-rated health, risk for DVT was attenuated (Model 4 HR 1.34, 95% CI: 0.97–1.84).

Table 4.

Incidence rates (IR) per 1000 person-years and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of work-related disability (one year before the date of official disability pension) after venous thromboembolism.

| Person-years | Work-related disability | Crude IR (95% CI) | Model 1 HR (95% CI) | Model 2 HR (95% CI) | Model 3 HR (95% CI) | Model 4 HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venous thromboembolism (VTE ) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No VTE | 702033 | 8948 | 12.6 (12.4–12.9) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| VTE | 1856 | 53 | 28.6 (21.8–37.4) | 1.37 (1.05–1.80) | 1.33 (1.02–1.75) | 1.26 (0.96–1.65) | 1.17 (0.89–1.53) |

|

| |||||||

| Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No DVT | 702706 | 8963 | 12.8 (12.5–13.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| DVT | 1183 | 38 | 32.1 (23.4–44.2) | 1.53 (1.11–2.11) | 1.50 (1.09–2.06) | 1.46 (1.06–2.01) | 1.34 (0.97–1.84) |

|

| |||||||

| Pulmonary embolism (PE) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No PE | 703216 | 8986 | 12.8 (12.5–13.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| PE | 673 | 15 | 22.3 (13.4–37.0) | 1.08 (0.65–1.79) | 1.04 (0.63–1.72) | 0.93 (0.56–1.54) | 0.89 (0.54–1.48) |

|

| |||||||

| Unprovoked VTE | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No unprovoked VTE | 702989 | 8967 | 12.8 (12.5–13.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Unprovoked VTE | 900 | 34 | 37.8 (27.0–52.9) | 1.67 (1.19–2.34) | 1.66 (1.18–2.33) | 1.57 (1.12–2.19) | 1.52 (1.09–2.14) |

|

| |||||||

| Provoked VTE | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No provoked VTE | 702933 | 8982 | 12.8 (12.5–13.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Provoked VTE | 956 | 19 | 19.8 (12.7–31.2) | 1.03 (0.66–1.63) | 0.98 (0.63–1.54) | 0.93 (0.59–1.46) | 0.83 (0.53–1.30) |

Model 1: Adjusted for age and sex

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking, education level and marital status

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking, education level, marital status, history of cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease

Model 4: Model 3 + self-rated general health

In subgroup analyses of unprovoked and provoked VTE in Table 4, subjects with unprovoked VTE had 67% higher risk of work-related disability than those without unprovoked VTE (Model 1 HR 1.67, 95% CI: 1.19–2.34), which remained elevated after multiple adjustments for clinical risk factors, co-morbidities and health status (HR 1.52, 95% CI: 1.09–2.14). In contrast, no association was found between provoked VTE and subsequent work-related disability (Table 4). Although the statistical power of further subgroup analyses was limited, the association appeared to be driven by unprovoked DVT (Table 5).

Table 5.

Subgroup analyses. Incidence rates (IR) per 1000 person-years and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of work-related disability (one year before the date of official disability pension) after venous thromboembolism (VTE): deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

| Person-years | Work-related disability | Crude IR (95% CI) | Model 1 HR (95% CI) | Model 2 HR (95% CI) | Model 3 HR (95% CI) | Model 4 HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unprovoked DVT | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No unprovoked VTE | 703343 | 8978 | 12.8 (12.5–13.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Unprovoked DVT | 546 | 23 | 42.1 (27.9–63.3) | 1.84 (1.22–2.78) | 1.83 (1.21–2.76) | 1.73 (1.14–2.60) | 1.70 (1.13–2.56) |

|

| |||||||

| Provoked DVT | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No provoked VTE | 703253 | 8986 | 12.8 (12.5–13.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Provoked DVT | 636 | 15 | 23.5 (14.2–39.1) | 1.22 (0.73–2.02) | 1.17 (0.70–1.93) | 1.19 (0.71–1.97) | 1.00 (0.60–1.67) |

|

| |||||||

| Unprovoked PE | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No unprovoked VTE | 703536 | 8990 | 12.8 (12.5–13.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Unprovoked PE | 353 | 11 | 31.1 (17.2–56.2) | 1.39 (0.77–2.51) | 1.38 (0.77–2.50) | 1.31 (0.72–2.36) | 1.25(0.69–2.26) |

|

| |||||||

| Provoked PE | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No provoked VTE | 703569 | 8997 | 12.8 (12.5–13.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Provoked PE | 320 | 4 | 12.5 (4.6–33.3) | 0.67 (0.25–1.78) | 0.62 (0.23–1.64) | 0.51 (0.19–1.37) | 0.50 (0.19–1.33) |

Model 1: Adjusted for age and sex

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking, education level and marital status

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking, education level, marital status, history of cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease

Model 4: Model 3 + self-rated general health

Discussion

We have, for the first time, shown that VTE was associated with subsequent work-related disability in a cohort recruited from the general working-age population. The risk of work-related disability after VTE was 30–62% higher when VTE exposure that occurred less than one year before the disability grant was included in the analyses. This relationship was most likely influenced by conditions other than VTE, as it is a prerequisite to be on sick leave at least one year in order to be eligible for a disability grant in Norway. The latter assumption was supported by the increased risk of work-related disability after a provoked VTE in these analyses. When the disability date was set one year before receiving disability pension, those with VTE had 17–37% higher risk of work-related disability than those without VTE. Subgroup analyses revealed that those with unprovoked VTE had 52–67% higher risk of work-related disability, whereas no association was found between provoked VTE and subsequent risk of disability. These latter findings support the notion that VTE by itself may result in work-related disability.

In subgroup analyses, we found that DVT rather than PE was associated with disability. PTS is the most common long-term complication of DVT. It occurs in up to half of the patients [9,10,34], and is a potentially debilitating condition. Because PTS symptoms can be aggravated by standing or walking, patients may be forced to alter their daily activities to include periods of rest. Symptoms may be intermittent or persistent, and severe manifestations such as chronic leg pain can limit activity and ability to work. In a study of 387 DVT patients followed for two years, development of PTS was accompanied by lower generic and disease specific quality of life [35]. Another study examined the long-term impact of PTS on the frequency of reported activity limitations in 52 patients 6–8 years after a symptomatic DVT using the SF-36 Health Survey quality of life questionnaire [17]. Although 42% of patients reported symptoms of swelling or pain at the follow-up interview, none reported having leg ulcers. The symptomatic patients described significantly more role limitations attributable to physical health, with a mean score of 36 compared with 78 for other patients. Overall, 16% of subjects reported that the symptoms interfered with their daily activities [17]. Other studies that used the SF-36 or similar questionnaires with variable length of follow-up also showed significantly reduced physical functioning scores and impaired activities of daily living, although with no specific mention of reduced working activity [14,15].

We did not find an association between PE and disability in our study. The most serious long-term consequences of PE are recurrent PE events and development of CTEPH. Although it is a potentially debilitating condition with high mortality rate [18], CTEPH after PE is rare as it occurs in 0.5–4% of the patients within 2 years [20–24,36]. Systematic radiological studies have shown that a DVT is found in only 50% of the PE patients [37], and accordingly, the reported cumulative incidence of PTS after a PE is about half of that found in DVT patients [13]. Thus, the relatively low number of patients with incident PE (35%) compared to DVT (65%) in combination with a rare occurrence of CTEPH and PTS in PE patients may explain why we did not find an association between PE and work-related disability in a general population of young and middle-aged persons.

Venous thrombosis is a multicausal disease that often occurs in conjunction with other medical conditions, such as cancer or arterial cardiovascular diseases, which may precede or follow a diagnosis of VTE [38–40]. Moreover, serious trauma or major surgery predispose to VTE [38,41], and may concomitantly lead to disability. Therefore, it may be difficult to distinguish whether it is the VTE event itself, or an underlying concurrent disease or condition that leads to disability. In our study, we used several approaches to elucidate whether VTE could be causally related to disability. Multivariable adjustments for history of co-morbidities had minor impact on the results. Moreover, when the date of work-related disability was set to one year before the date a disability pension was granted, those with DVT still had a 50% higher risk of disability compared to those without VTE, indicating that the DVT was not merely a result of an underlying disease already impending a disability pension grant. Among those who received disability pension, 64% of the events were unprovoked, which means that they occurred in the absence of cancer, surgery, trauma or acute medical conditions. Further subgroup analyses revealed that this risk was particularly related to unprovoked DVT. The risk of recurrence is higher in patients with an unprovoked first event [7–9], and recurrent VTEs are associated with higher risk of the PTS [11]. Thus, the observed increased risk of disability after unprovoked DVT may potentially be explained by more recurrences and PTS in these patients. Although previous studies on the risk of PTS did not explicitly investigate young subjects, and used somewhat different definitions of provoking factors, the risk of PTS seems to be independent of whether the VTE was unprovoked [11,42]. Unfortunately, we did not have information on the distribution of recurrences and PTS during follow-up in our VTE-patients, and could therefore not explore this hypothesis any further.

Adjustments for self-rated general health attenuated the risk estimates in our study. Self-rated health is correlated with bodily sensations and symptoms that can reflect disease in clinical and pre-clinical stages, and may reflect co-morbidities better than additive measures of diseases. Poor health status in itself is not sufficient to receive disability pension, but self-rated health is related to several health outcomes and diagnoses that qualify for disability pension [43,44]. Although it is reasonable that poor health status would be associated with elevated risk of future VTE, the impact of self-rated health on risk of VTE has, to our knowledge, never been investigated. In our study, self-rated health was assessed on average 6 years before the VTE. From a causal point of view, it is impossible to distinguish whether subjects were granted disability pension due to a VTE resulting from a poor health status, or whether poor health status was related to development of other diseases during follow-up (e.g. cancer) that were also associated with VTE. However, the increased risk of work-related disability after an unprovoked VTE (i.e. VTE not related to cancer, acute medical conditions or surgical procedures) indicates that VTE could be an important factor for disability independent of co-morbidities.

Although the incidence of VTE increases markedly with age, the absolute risk difference of disability was 19 per 1000 per year in patients with DVT compared to those without DVT in this rather young population of working-age subjects. A recent Canadian study reported that direct medical costs during the two years following a diagnosis of DVT were 35% higher for patients who developed PTS [45]. Our finding that DVT, in particular unprovoked DVT, is associated with subsequent work-related disability suggests that indirect costs due to loss of work years add to the economic burden of VTE.

The major strengths of our study are the large cohort representative of the working-age population, long follow-up time, as well as the well-validated VTE exposure. Our outcome measure of work-related disability (disability pension) came from routinely collected official registries with very high accuracy. The main causes of disability pension in Norway are reported to be similar to other member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in the same time frame [46]. Some limitations merit consideration. Unfortunately, we had no information about the incidence of PTS or recurrence during follow-up in our VTE patients. Moreover, we did not have information on concurrent diseases (e.g. cancer and cardiovascular diseases) that occurred during follow-up, and we were not able to distinguish whether VTE was accompanied by other diagnoses for disability pension. However, the risk was still significantly higher in patients with unprovoked VTE, supporting that the risk could not be entirely explained by other concomitant diseases. Moreover, major bleeding as a consequence of VTE treatment could potentially lead to disability. Unfortunately, we did not have information on bleeding complications in our study. However, the absolute rates of major intracranial bleeding in patients on anticoagulant therapy are <1%, and therefore the low number of patients with major bleeding events would presumably not influence our results.

In conclusion, we found that VTE was associated with subsequent permanent work-related disability in a cohort recruited from the general population at working ages. DVT was more strongly associated with disability than PE, a finding that may be explained by the higher rate of burdensome and potentially debilitating PTS in patients with DVT than those with PE. Our findings suggest that indirect costs due to loss of work time add to the economic burden of VTE.

Essentials.

The burden of venous thromboembolism (VTE) related to permanent work-related disability is unknown.

In a cohort of 66005 individuals, the risk of work-related disability after a VTE was assessed.

Unprovoked VTE was associated with 52% increased risk of work-related disability.

This suggests that indirect costs due to loss of work time may add to the economic burden of VTE.

Acknowledgments

The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (The HUNT Study) is a collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology NTNU), Nord-Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Health Authority, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Dr. Hani Atrash, former Director of the Division of Blood Disorders at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), was instrumental in facilitating the CDC-Norway collaboration that resulted in this analysis.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There are no conflicts of interest by any of the authors.

Addendum

S. C. Grosse, J.-B. Hansen, and F. E. Skjeldestad were responsible for the conception and design. S. K. Braekkan, J.-B. Hansen, I. A. Naess, S. Krokstad, and S. C. Cannegieter collected data. S. K. Braekkan carried out analyses and drafted the manuscript. J.M. Tsai, E. M. Okoroh, S. C. Grosse, I. A. Naess, S. Krokstad, S. C. Cannegieter J.-B. Hansen, and F. E. Skjeldestad interpreted results and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. S. K Braekkan had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Naess IA, Christiansen SC, Romundstad P, Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Hammerstrom J. Incidence and mortality of venous thrombosis: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:692–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107:I4–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tagalakis V, Patenaude V, Kahn SR, Suissa S. Incidence of and mortality from venous thromboembolism in a real-world population: the Q-VTE Study Cohort. Am J Med. 2013;126:832 e13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alikhan R, Peters F, Wilmott R, Cohen AT. Fatal pulmonary embolism in hospitalised patients: a necropsy review. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:1254–7. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.013581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baglin T, Douketis J, Tosetto A, Marcucci M, Cushman M, Kyrle P, Palareti G, Poli D, Tait RC, Iorio A. Does the clinical presentation and extent of venous thrombosis predict likelihood and type of recurrence? A patient-level meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2436–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prandoni P, Kahn SR. Post-thrombotic syndrome: prevalence, prognostication and need for progress. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:286–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baglin T, Luddington R, Brown K, Baglin C. Incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism in relation to clinical and thrombophilic risk factors: prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2003;362:523–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansson PO, Sorbo J, Eriksson H. Recurrent venous thromboembolism after deep vein thrombosis: incidence and risk factors. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:769–74. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulman S, Lindmarker P, Holmstrom M, Larfars G, Carlsson A, Nicol P, Svensson E, Ljungberg B, Viering S, Nordlander S, Leijd B, Jahed K, Hjorth M, Linder O, Beckman M. Post-thrombotic syndrome, recurrence, and death 10 years after the first episode of venous thromboembolism treated with warfarin for 6 weeks or 6 months. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:734–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn SR, Shrier I, Julian JA, Ducruet T, Arsenault L, Miron MJ, Roussin A, Desmarais S, Joyal F, Kassis J, Solymoss S, Desjardins L, Lamping DL, Johri M, Ginsberg JS. Determinants and time course of the postthrombotic syndrome after acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:698–707. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-10-200811180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH, Frulla M, Marchiori A, Bernardi E, Tormene D, Mosena L, Pagnan A, Girolami A. Below-knee elastic compression stockings to prevent the post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:249–56. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn SR, Morrison DR, Cohen JM, Emed J, Tagalakis V, Roussin A, Geerts W. Interventions for implementation of thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical and surgical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD008201. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008201.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohr DN, Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Petterson TM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ. The venous stasis syndrome after deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1249–56. doi: 10.4065/75.12.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn SR, Elman EA, Bornais C, Blostein M, Wells PS. Post-thrombotic syndrome, functional disability and quality of life after upper extremity deep venous thrombosis in adults. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:499–502. doi: 10.1160/TH04-10-0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delis KT, Bountouroglou D, Mansfield AO. Venous claudication in iliofemoral thrombosis: long-term effects on venous hemodynamics, clinical status, and quality of life. Ann Surg. 2004;239:118–26. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000103067.10695.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahn SR, Ducruet T, Lamping DL, Arsenault L, Miron MJ, Roussin A, Desmarais S, Joyal F, Kassis J, Solymoss S, Desjardins L, Johri M, Shrier I. Prospective evaluation of health-related quality of life in patients with deep venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1173–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beyth RJ, Cohen AM, Landefeld CS. Long-term outcomes of deep-vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1031–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fedullo P, Kerr KM, Kim NH, Auger WR. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Resp Critic Care Med. 2011;183:1605–13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1854CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCabe C, White PA, Hoole SP, Axell RG, Priest AN, Gopalan D, Taboada D, Mackenzie Ross RV, Morrell NW, Shapiro LM, Pepke-Zaba J. Right ventricular dysfunction in chronic thromboembolic obstruction of the pulmonary artery. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014;116:355–63. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01123.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klok FA, van Kralingen KW, van Dijk AP, Heyning FH, Vliegen HW, Huisman MV. Prospective cardiopulmonary screening program to detect chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension in patients after acute pulmonary embolism. Haematologica. 2010;95:970–5. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.018960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becattini C, Agnelli G, Pesavento R, Silingardi M, Poggio R, Taliani MR, Ageno W. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after a first episode of pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2006;130:172–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dentali F, Donadini M, Gianni M, Bertolini A, Squizzato A, Venco A, Ageno W. Incidence of chronic pulmonary hypertension in patients with previous pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2009;124:256–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pengo V, Lensing AW, Prins MH, Bertolini A, Squizzato A, Venco A, Ageno W. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2257–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poli D, Miniati M. The incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension following a first episode of pulmonary embolism. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:392–7. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328349289a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshimi S, Tanabe N, Masuda M, Sakao S, Uruma T, Shimizu H, Kasahara Y, Takiguchi Y, Tatsumi K, Nakajima N, Kuriyama T. Survival and quality of life for patients with peripheral type chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ J. 2008;72:958–65. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roman A, Barbera JA, Castillo MJ, Munoz R, Escribano P. Health-related quality of life in a national cohort of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Arch Bronconeumol. 2013;49:181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahn SR, Hirsch A, Beddaoui M, Akaberi A, Anderson D, Wells PS, Rodger M, Solymoss S, Kovacs MJ, Rudski L, Shimony A, Dennie C, Rush C, Geerts WH, Hernandez P, Aaron S, Granton JT. “Post-Pulmonary Embolism Syndrome” after a First Episode of PE: Results of the E.L.O.P.E. Study. American Society of Hematology (ASH) 57th Annual Meeting & Exposition; 2015; Abstract 650. Available at https://ash.confex.com/ash/2015/webprogram/Paper79084.htmlcited May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Donnell TF, Jr, Browse NL, Burnand KG, Thomas ML. The socioeconomic effects of an iliofemoral venous thrombosis. J Surg Res. 1977;22:483–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(77)90030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K, Holmen TL, Midthjell K, Stene TR, Bratberg G, Heggland J, Holmen J. Cohort Profile: the HUNT Study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:968–77. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobsen BK, Eggen AE, Mathiesen EB, Wilsgaard T, Njolstad I. Cohort profile: The Tromso Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quist-Paulsen P, Naess IA, Cannegieter SC, Romundstad PR, Christiansen SC, Rosendaal FR, Hammerstrom J. Arterial cardiovascular risk factors and venous thrombosis: results from a population-based, prospective study (the HUNT 2) Haematologica. 2010;95:119–25. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.011866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braekkan SK, Mathiesen EB, Njolstad I, Wilsgaard T, Stormer J, Hansen JB. Family history of myocardial infarction is an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolism: the Tromso study. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1851–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braekkan SK, Borch KH, Mathiesen EB, Njolstad I, Wilsgaard T, Hansen JB. Body height and risk of venous thromboembolism: The Tromso Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:1109–15. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Cogo A, Cuppini S, Villalta S, Carta M, Cattelan AM, Polistena P, Bernardi E, Prins MH. The long-term clinical course of acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:1–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-1-199607010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, Holcroft CA, Shrier I, Miron MJ, Roussin A, Desmarais S, Joyal F, Kassis J, Solymoss S, Desjardins L, Johri M, Ginsberg JS. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1105–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miniati M, Monti S, Bottai M, Scoscia E, Bauleo C, Tonelli L, Dainelli A, Giuntini C. Survival and restoration of pulmonary perfusion in a long-term follow-up of patients after acute pulmonary embolism. Medicine. 2006;85:253–62. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000236952.87590.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Langevelde K, Sramek A, Vincken PW, van Rooden JK, Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC. Finding the origin of pulmonary emboli with a total-body magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging technique. Haematologica. 2013;98:309–15. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.069195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samama MM. An epidemiologic study of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis in medical outpatients: the Sirius study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3415–20. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.22.3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sorensen HT, Horvath-Puho E, Sogaard KK, Christensen S, Johnsen SP, Thomsen RW, Prandoni P, Baron JA. Arterial cardiovascular events, statins, low-dose aspirin and subsequent risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based case-control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:521–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cronin-Fenton DP, Sondergaard F, Pedersen LA, Fryzek JP, Cetin K, Acquavella J, Baron JA, Sorensen HT. Hospitalisation for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients and the general population: a population-based cohort study in Denmark, 1997–2006. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:947–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogers MA, Levine DA, Blumberg N, Flanders SA, Chopra V, Langa KM. Triggers of hospitalization for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2012;125:2092–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.084467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stain M, Schonauer V, Minar E, Bialonczyk C, Hirschl M, Weltermann A, Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. The post-thrombotic syndrome: risk factors and impact on the course of thrombotic disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2671–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halford C, Wallman T, Welin L, Rosengren A, Bardel A, Johansson S, Eriksson H, Palmer E, Wilhelmsen L, Svardsudd K. Effects of self-rated health on sick leave, disability pension, hospital admissions and mortality. A population-based longitudinal study of nearly 15,000 observations among Swedish women and men. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE, Everson SA, Cohen RD, Salonen R, Tuomilehto J, Salonen J. Perceived health status and morbidity and mortality: evidence from the Kuopio ischaemic heart disease risk factor study. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:259–65. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guanella R, Ducruet T, Johri M, Miron MJ, Roussin A, Desmarais S, Joyal F, Kassis J, Solymoss S, Ginsberg JS, Lamping DL, Shrier I, Kahn SR. Economic burden and cost determinants of deep vein thrombosis during 2 years following diagnosis: a prospective evaluation. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2397–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prinz C. OECD Policy Brief 2003. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; Disability programmes in need of reform. [Google Scholar]