Abstract

Although data from parent-implemented Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions have shown positive effects on decreasing core symptoms of autism, there has been limited examination of the effectiveness of Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions in community settings. In addition, parent perspectives of their involvement in parent-implemented early intervention programs have not been well studied. Using both qualitative and quantitative data to examine parent perspectives and the perceived feasibility of parent training by community providers, 13 families were followed as they received training in the Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Intervention, Project ImPACT. Data indicate that parent training by community providers is feasible and well received, and parents find value in participating in intervention and perceive benefit for their children. Recommendations for adaptation of program elements and future research are discussed.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, early intervention, evidence-based practice, parent perceptions, toddlers

Introduction

The number of children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is currently 1 in 68, and identification is occurring at increasingly early ages. A diagnosis by an experienced professional is considered very reliable by age 2 (Lord et al., 2006). In a recent study of prevalence rates, 44% of children with ASD had received a comprehensive evaluation before age 3, and mention of developmental concerns was documented before age 3 for almost 89% of these children (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2014). Many families of children with early ASD symptoms seek services prior to a diagnosis due to language and social delays. A growing body of research suggests that beginning intervention early can greatly improve outcomes for children at risk for ASD. Current recommendations suggest initiating intervention as soon as a child receives a diagnosis (National Research Council, 2001; Rogers, 1998). Intervening at the first signs of ASD risk, however, prior to a formal diagnosis being made, may be even more powerful and prevent the onset of symptoms for some children (Dawson, 2008). Treating ASD has a societal cost of up to US$2.4 million over the lifespan (Buescher et al., 2014). Effective early intervention (EI) can greatly decrease the lifespan costs of supporting an individual with ASD (Jarbrink and Knapp, 2001; Penner et al., 2015) and continues to be an important priority to best support children and families.

In addition to intervening as early as possible, it has been long established that parent involvement is crucial for optimal child outcomes (Maglione et al., 2012; National Research Council, 2001). Several recent randomized trials of parent-implemented Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral interventions (NDBIs) for ASD have shown positive effects on core symptoms of the disorder (Kasari et al., 2014; Rogers et al., 2014; Wetherby et al., 2014). NDBIs blend both behavioral and developmental strategies to address core symptoms of ASD, as well as build specific communication and cognitive skills, and are currently considered state-of-the-art treatment (e.g. Dawson et al., 2010; Schreibman et al., 2015; Stahmer et al., 2010). In parent-implemented treatment, parents learn to use specific strategies from a therapist and are taught to integrate evidence-based strategies into their daily routines with their young child. In addition to effectively promoting child progress, parent-implemented intervention may decrease stress in some parents (Estes et al., 2014; Reed et al., 2013). Although we are not suggesting that parents should be required to take on the responsibility of being a child's sole interventionist (Stahmer and Pellecchia, 2015), parent-implemented intervention, if done well, may be one way to maximize learning opportunities for very young children with ASD, engage parents in the intervention process early, and increase parents' feelings of competence and empowerment.

While efficacy data for early parent-implemented interventions are promising (e.g. Kasari et al., 2014; Rogers et al., 2014; Wetherby et al., 2014), there is currently only one parent-implemented ASD intervention with demonstrated effectiveness in community trials (Solomon et al., 2014). Community implementation of evidence-based practices for ASD and other childhood mental health disorders has historically been a challenge for the field (Bondy and Brownell, 2004; Hess et al., 2008; Perkins et al., 2007; Stahmer, 2005). Currently, public EI systems typically address family and child needs via transdisciplinary assessment and parent guidance, rather than disability-specific interventions. However, general developmental guidance is not an intervention approach that has shown positive effects for children with ASD (Ingersoll et al., 2012). Evidence-based NDBIs are developmentally appropriate for young children, but are not widely delivered in community settings (Hess et al., 2008; Stahmer et al., 2005). Family involvement is also not widely implemented in community settings, despite being a value and mandate of publicly implemented EI systems (34 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Parts 300 and 303). Traditional ASD programs do not include parent coaching, and many community providers are not specifically trained in adult learning models (Coogle et al., 2013; Hume et al., 2005). Given the potential economic and developmental benefit of EI for ASD with high levels of family involvement, it is imperative that up-to-date, evidence-based practices that meet the needs of toddlers with risk of ASD and their families are translated effectively into community settings.

One of the challenges in moving evidence-based practices into the community is the contextual difference between research settings and routine care. In research settings, families who receive intervention are often highly motivated and meet strict inclusion criteria, intervention is typically delivered by highly trained lab staff (sometimes with the direct oversight of the intervention developer), and project resources are sizable. In the community, however, these same conditions are not in place, and as a result, there is often a poor fit between the intervention practices as designed by researchers and the ability of community providers to deliver those interventions as intended. One method of addressing this issue is active and direct collaboration between research and community stakeholders. This can increase understanding of varying perspectives regarding the benefits and barriers of specific practices and their use in EI services (Hoagwood et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2003; Schwartz, 1999). Fully understanding the benefits and barriers of specific practices can inform efforts to improve the fit between specific services and the community, thus ultimately facilitating implementation.

To that end, there has been limited study of parent perspectives of participation in EI. Although parent satisfaction with EI services is traditionally quite high as measured by brief surveys (Bailey et al., 2004; McNaughton, 1994; Summers et al., 2005), there is little examination of parents' perspectives around the perceived effectiveness of the intervention or the feasibility of implementing a specific intervention themselves. A recent qualitative study enlisted parents of children at risk for ASD enrolled in a randomized trial of a parent-implemented EI to discuss their experiences of the process (Freuler et al., 2013). Parents reported that participation in the project helped them become ready for additional EI and understand their child's development. They discussed the value of the personal relationship with professionals as essential to increased feelings of support and a positive experience in EI. Challenges with intervention included traveling to evaluations, anxiety around evaluation outcomes, and finding time to do the intervention on their own. Limited information was obtained regarding parent perspectives on the content of the parent-implemented strategies, particularly beyond the intervention period.

An additional factor important to the effectiveness of parent-implemented interventions is how well parents are able to learn and utilize the intervention strategies themselves. Measuring change in parent behavior while interacting with their child from pre- to post-treatment is the most proximal outcome of parent-mediated intervention. Parent-implemented NDBIs include measures of treatment integrity (Schreibman et al., 2015) to assess parent behavior, as fidelity of implementation of the intervention is likely a mediating factor in affecting child outcome (Durlak and DuPre, 2008; Stahmer and Gist, 2001). Efficacy trials examining the use of NDBIs by parents indicate that they can learn the strategies with a high degree of fidelity when coached by highly trained research staff (Aldred et al., 2004; Kaiser et al., 2000; Koegel et al., 1996; Mahoney and Perales, 2003). Less information is available regarding the ability of community providers to teach parents to implement these relatively complex interventions successfully (Vismara et al., 2009), and a recent project by Solomon et al. (2014) suggests that community EI providers can successfully implement development strategies with fidelity. This transfer of knowledge from expert trainer to community provider to parent is essential if evidence-based parent-implemented interventions are to be successfully delivered in community settings.

This study originated in a community-partnered participatory research model (Jones and Wells, 2007) in which a team of researchers, community providers, funding agency representatives, and parents formed a partnership called the “Southern California BRIDGE Collaborative” to develop a community-wide, sustainable plan for serving infants/toddlers at risk for ASD (see Brookman-Frazee et al., 2012). The group used a collaborative process to identify methods to build community capacity to serve children at risk for ASD and their families. Through a lengthy review process in both the collaborative group and the community (as described in Brookman-Frazee et al., 2012), the BRIDGE Collaborative selected Project ImPACT (Improving Parents as Communication Teachers; Ingersoll and Dvortcsak, 2010) as a best-fit treatment for community implementation to optimally support families of young children with ASD. Project ImPACT is an NDBI that teaches families a combination of naturalistic developmental and behavioral intervention techniques to improve child's social engagement, language abilities, imitation skills, and play (Ingersoll and Dvortcsak, 2010). Project ImPACT has published publicly available training manuals for therapists and parents and options for group and individual implementation of the program. Additionally, the program developers supported a train-the-trainer model, where a program supervisor can learn to train other local providers in the program. Project ImPACT strategies have a long history of evidence in the literature (see National Standards Project (NSP), 2009). Recent studies using rigorous single-subject methodology reported that children receiving the intervention demonstrated significant gains in social communication skills and a significant decrease in autistic symptomatology. Parents have been shown to use the intervention with fidelity, and they report a significant decrease in parenting stress. Additionally, both parents and therapists rated the acceptability of the intervention very highly (Ingersoll, 2009, 2011; Ingersoll al., 2005).

The purpose of this study was to examine parent perspectives and the initial impact on parent behaviors of Project ImPACT for toddlers at risk for ASD when delivered by community providers in routine care service settings. Specifically, mixed quantitative and qualitative methods were used to assess (1) observed changes in parent use of strategies to facilitate their child's social communication skills following community-implemented Project ImPACT and (2) parent perceptions of effectiveness and feasibility of Project ImPACT.

Method

Data for this study were collected as part of a pilot study examining initial impact and feasibility of training EI providers to deliver Project ImPACT to toddlers with ASD and their families (Stahmer et al., 2014). A mixed qualitative and quantitative design was used to examine parent perspectives of treatment (Aim 1) and parent behavior change (Aim 2) when community providers delivered Project ImPACT. Specifically, qualitative and quantitative methods were used to measure Aim 1 (parent perceptions from interviews and surveys), and quantitative and observational methods were used to examine Aim 2 (changes in observed parent behaviors during parent–child interactions). As it is appropriate for subjective experiences (Marshall and Rossman, 2006), qualitative methods were used to complement and expand quantitative findings and capture the richness and potential diversity of parents' perceptions, as well as to gather information for future adaptations of the intervention.

Participants

Participants included a total of 13 parents and their children with risk of ASD, recruited from four community programs enrolled in the pilot study. Families were eligible to participate if they (1) were referred to a community provider trained in Project ImPACT for parent education/training by the local service system, (2) had a child with a primary diagnosis of ASD or risk of ASD based on evaluations conducted through services in the community (i.e. primarily through local Part C services), (3) had a child under 24 months of age at intake, (4) spoke English or Spanish as the primary language at home, and (5) had received no prior autism-specific intervention services. Parents of children with significant organic brain damage, major medical problems, or significant sensory impairment (blindness or deafness) were excluded. These broad criteria ensured that we measured the intervention use based on service system eligibility in the community. Of the 13 families who enrolled, 11 completed the study. One family moved away before completion of the intervention, and another child left the participating program (moved to a more intensive program) before completion of the intervention. All families except one participated in the intervention through Part C EI services. The child that did not qualify for Part C was the younger sibling of a child with autism who was showing significant red flags. The child's family volunteered for the study and was seen through one of the agencies pro bono.

Mean child age at intake was 15 months (standard deviation (SD) = 3.01 months; range = 8–21 months), and a majority (76%) of families self-identified as Caucasian (15% as Hispanic and 8% Pacific Islander). In all, 85% of participating children were male. For 100% of participating families, the primary family participant was the child's biological mother and 85% were married. More than half (n = 7, 54%) of the participating children had received some kind of EI services for speech or motor delays prior to intake. All children were identified to be at risk for an ASD prior to referral to the study based on having early symptoms of ASD by local Part C or in community agencies. All children referred to the study were eligible for community intervention services, and therefore were considered the population of interest (families being served in community settings). One child had been previously diagnosed with Pervasive Developmental Disorder—Not Otherwise Specified and two with Autistic Disorder by community psychologists. Of that, 54% of the children had older siblings with ASD. A majority of children (69%, n = 9) received scores indicating “Concern” on the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales (CSBS) Infant–Toddler Checklist (CSBS; Wetherby and Prizant, 2002) and/or parents reported developmental concerns (92%, n = 12). Mother's mean age at intake was 34.9 years (SD = 3.99 years; range = 27–40 years). All mothers reported at least some college education, with 85% having a college degree.

Procedure

Four community intervention agencies enrolled in the pilot study. Participating agencies consisted of a school district EI program, an autism-specific behavioral service agency, a speech and language therapy center, and a hospital autism center. All providers served children with ASD or risk of ASD under age 3 funded through Part C (California Early Start). From these programs, eight providers who worked at agencies participating in the Collaborative, but who were not members of the Collaborative themselves, received training in Project ImPACT from the program developers and the BRIDGE Collaborative. They were recommended by their agency leader and indicated willingness to participate in the study. All held an MA degree in their primary disciplines: two marriage and family child counselors (MFCC), a behavior specialist, three speech and language pathologists, and two EI special education teachers. On average, they had 7.4 years of experience with infants/toddlers (range = 3–15 years; Rieth et al., in preparation; contact the authors for additional information).

Training for providers participating in the study consisted of a 2-day workshop (16 h) on Project ImPACT delivered by the model developers' team and BRIDGE Collaborative members. Training consisted of didactic presentations, video examples, and role-playing activities, as well as small and large group discussions. All eight participating providers received the initial training at the same time. Based on the young age of the children being targeted for intervention, training specifically focused on using the intervention to address developmentally appropriate play and pre-linguistic communication skills. In addition to Project ImPACT content, therapists received supplemental training in adult–child dyadic interaction and considering individual child differences (e.g. hypo- or hyperreactivity to sensory experiences and muscle tone) as well as reflective practice. This information was added to training based on input from community and BRIDGE Collaborative members. After training, providers delivered Project ImPACT to families as routine care at their community program, with support from BRIDGE Collaborative members and the research team. Ongoing support included bimonthly performance feedback via video or live observation regarding Project ImPACT implementation from a trained BRIDGE Collaborative member, for a period of approximately 1 month (average number of feedback sessions across all therapists = 2.13; SD = 0.99). All therapists received feedback sessions, regardless of performance. This feedback consisted of the BRIDGE member completing the fidelity checklist on the therapist's implementation of Project ImPACT and coaching strategies and sharing the checklist and comments with the therapist. This process occurred either in-person (live observation appointments) or via electronic communication (video observation appointments).

Data for this study were collected by the research team and included parent–child interactions video-recorded pre-and post-treatment, satisfaction surveys, and telephone interview responses. Prior to beginning treatment, parents attended an assessment session to complete measures, including a brief video of parent–child interactions and semi-structured child assessments. Parents and children then completed 12 weeks of parent coaching in Project ImPACT (see below) either in their home or a clinic setting depending on the agency from which they received the intervention. After completing the 12 treatment sessions, parents attended an exit assessment session and completed the same measures and a satisfaction survey. Parents also completed a telephone interview within 1 month of completing the treatment. Interviews were conducted by phone and lasted an average of 13 min (range = 6–22 min). Parents received a small monetary compensation for their participation in the larger study that included all interviews and assessments. An Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Project ImPACT intervention

Intervention content

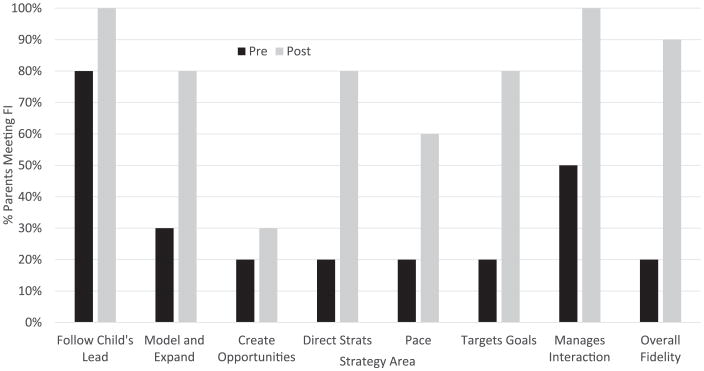

Families received Project ImPACT, an evidence-based treatment for children with ASD. Project ImPACT is a manualized, parent-implemented program that teaches parents to facilitate their child's development during daily activities and is based on the manual Teaching Social Communication to Children with Autism (Ingersoll and Dvortcsak, 2010). Through Project ImPACT, parents learn developmental and naturalistic behavioral techniques. The developmental techniques are designed to increase parent responsiveness to their child's subtle communication skills and sensory needs, as well as increase child's engagement and create opportunities for initiation. The naturalistic behavioral techniques build on the interactive techniques and teach parents to use specific prompts and reinforcement strategies to increase the complexity of their child's responses. An overview and progression of specific techniques are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview and progression of specific techniques.

Source: reproduced with permission from Guilford Press, Ingersoll and Dvortcsak (2010).

Intervention delivery

Parents received a 12-week Project ImPACT curriculum to support their use of strategies to facilitate interaction and skill building in their children during daily routines and activities. Parents received the Teaching Social Communication for Children with Autism manual and parent coaching for 1 h per week from community therapists trained in the model as part of the research project. The parent manual describes each intervention strategy and includes weekly reading-based homework and handouts that highlight important information. Session structure typically included a review of the previous weeks' homework, a discussion of the strategy or strategies to be learned in the current session, therapist modeling of the strategies and parent practice with therapist feedback, closing with a summary of the session, and a plan for at-home practice and homework. Specific individualized social communication goals for each child were developed with parents during the first or second intervention session and targeted throughout treatment. All parents completed the program as reported by community therapists. Families were typically enrolled with community agencies for slightly longer than 12 weeks based on cancelations, holidays, and other scheduling constraints. Average length of time to complete the program across families was 4.7 months (SD = 1.13 months).

Measures

Parent fidelity of implementation was coded by research team members familiar with Project ImPACT and trained to score fidelity of implementation using developer-derived methods until they met an 80% inter-rater reliability criterion (i.e. 90% of strategies were rated within one point of the master key). Fidelity of implementation of Project ImPACT was scored on a 10-min video-recorded play segment completed by the parent with their child prior to beginning Project ImPACT and after completing the program. Coders were blind to the pre- versus post-treatment status while scoring videos. Parents were asked to play with their children as they typically would at home. Coders rated the parent's implementation of each Project ImPACT technique on a 1–5 Likert scale, where 1 indicated that parent did not implement the technique throughout the session and 5 indicated that the parent implemented the technique competently and consistently throughout the session. A score of 4 or 5 was considered meeting fidelity for any individual technique in Project ImPACT. Composite scores for seven groups of techniques (Follows Child's Lead, Models and Expands Communication and Play, Creates Opportunities for Child to Respond, Uses Direct Teaching Strategies, Paces the Interaction Successfully, Targets Goals, and Manages Interaction) were generated by calculating the average rating of the group of techniques. Additionally, an overall composite was created by averaging all individual techniques (Overall Fidelity). Parents were considered to have met fidelity when all of their composite scores were 3.5 or higher. This allowed for accurate use (rated 4 or 5) of a majority of the techniques of a strategy without penalizing parents for missing one technique during the session. Fidelity definitions are available from the authors.

The parent training program family satisfaction survey was designed by the research team to assess parent perceptions of (1) program content, (2) program design, and (3) perceived effectiveness. The survey was based on a survey used by the intervention developer in previous projects. The survey consists of 29 items, 27 of which use a seven-point Likert-type scale for responses ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (7). The last two questions are open-ended to capture any additional feedback parents may have. Scores are computed by averaging responses across all items to create an overall satisfaction rating.

Semi-structured exit interview

The research team and community partners created an open-ended, semi-structured exit interview using established methods for question construction, order, and format (Bourque and Fielder, 2003). The interview was designed to capture parent observations, feelings of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, and critical feedback about intervention implementation and family outcomes. A telephone interview approach was chosen to ensure the largest response and ease of scheduling for parent participants. A researcher unrelated to the study conducted the interviews to reduce bias.

The interview consisted of four different sections designed to gather information about the benefits and challenges of the intervention's most prominent features including (1) Project ImPACT techniques and implementation, (2) Project ImPACT session structure and materials, (3) impact of participating in Project ImPACT on child and family, and (4) recommendations for changes to the intervention materials, parent training process, or implementation. A complete list of interview questions is available from the authors.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) were used to examine changes in each of the parent behaviors measured on the fidelity of implementation observational coding system. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize parent perceptions on the satisfaction survey measure. Qualitative data were analyzed using a coding, consensus, and comparison (Willms et al., 1990) approach guided by grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). Two investigators independently coded transcripts at a general level to condense data into analyzable units (themes). Portions of transcripts were assigned codes based on a priori (i.e. questions in the interview guide) and emergent themes. Themes were examined across interviews and described using representative quotes as exemplars. Inter-rater reliability was assessed for each transcript. Disagreements in code definition or characterization during development were resolved through discussion between the author and principal investigator. Transcripts were coded with overall reliability of 90.7%.

Results

Changes in parent behaviors during parent–child interactions (Project ImPACT fidelity)

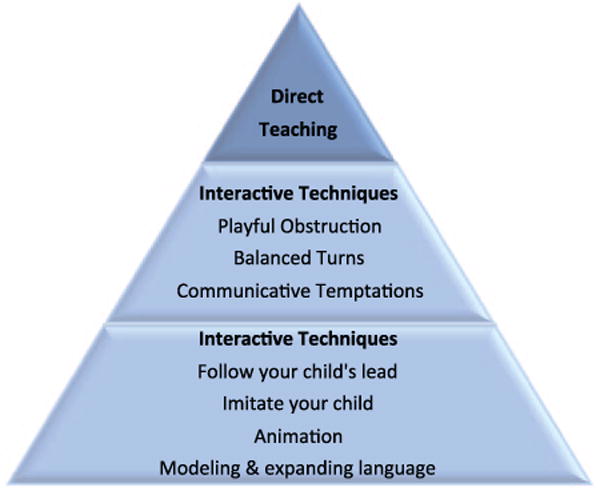

Significant improvements in parents' fidelity were observed from baseline to 12 weeks (F(1, 9) = 12.0; p < 0.001; see Table 1 for change in individual fidelity strategies).When averaged across all strategies, 20% of parents were considered to have met overall fidelity (average of 3.5 or higher overall) at baseline compared to 90% of parents at 12 weeks. At baseline, parents scored highest on Follows Child's Lead (mean (M) = 3.73) and Manages Interaction strategies (M = 3.30) and lowest on Creates Opportunities (M = 2.65) and Paces the Interaction Successfully (M = 2.77). After training, parents made statistically significant improvements in all strategies. When looking at the percentage of parents who met the highest fidelity standard on each individual strategy, a total of 80% of parents met fidelity (received a score of 4 or 5) on every individual item following training, with the exceptions of creating opportunities and pacing the interaction (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Family participant demographics.

| Children | |

|---|---|

| Age at intake | M = 15 months; SD = 3.01 |

| Child gender | Male = 85% (n = 11) |

| Family race/ethnicity | Caucasian = 76%; Hispanic = 15%; Pacific Islander = 8% |

| Received prior early intervention | 54% (n = 7) |

| Older sibling with ASD | 54% (n = 7) |

| CSBS score | Demonstrating concern = 69% (n = 9) |

| Parent developmental concerns reported | Yes = 92% (n = 12) |

| Caregivers | |

| Parent participant | Mother = 100% |

| Age at intake | M = 34.9 years; SD = 3.99 |

| Education | Some college = 100%; degree = 85% |

M: mean; SD: standard deviation; ASD: autism spectrum disorder; CSBS: Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales.

Demographic information for caregivers and children who received Project ImPACT in the community.

Figure 2.

Percentage of parents meeting fidelity at pre- and post-intervention by strategy.

Parent perceptions of adapted Project ImPACT

Results are reported in terms of primary themes that emerged from the data. Descriptions of themes are accompanied by survey data and quotes from interview transcripts to illustrate each area. Quantitative survey data are also presented in Table 2. All 11 families who completed intervention responded to the parent satisfaction survey. Nine parents were reached for the exit interview. The other two families could not be reached for the exit interview after repeated attempts. Satisfaction data are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Parent fidelity of implementation by strategy.

| Strategies | Individual techniques included | Pre-training M (SD) | Post-training M (SD) | F-value (1, 9) (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follows Child's Lead | Lets child choose activity Face-to-face and at child's level Joins in child's play and imitates child Adjusts animation to child's needs |

3.73 (0.46) | 4.2 (0.51) | 5.33 (p = 0.046) |

| Models and Expands Communication and Play | Gives meaning to child's actions Adjusts language to child's developmental level Models communication/play around child's focus Models communication/play at child's developmental level Expand child's communication |

3.26 (0.42) | 3.98 (0.47) | 81.0 (p = 0.000) |

| Creates Opportunities for Child to Respond | Uses playful obstruction, balanced turns, and communicative temptations effectively Helps child anticipate interruption |

2.65 (0.92) | 3.23 (0.55) | 5.79 (p = 0.019) |

| Uses Direct Teaching Strategies | Prompts child for a more complex response Waits for child initiation before prompting Provides time for child to respond Provides immediate reinforcement for correct responding With holds reinforcement for inappropriate/incorrect responses Adjusts prompt level to promote spontaneity |

2.99 (0.60) | 3.75 (0.35) | 17.76 (p = 0.002) |

| Paces the Interaction Successfully | Uses interactive techniques to keep child engaged Uses interactive techniques to provide initiation opportunities Uses direct techniques to increase skill complexity when child is motivated |

2.77 (0.74) | 3.6 (0.49) | 12.10 (p = 0.007) |

| Targets Goals |

Targets: Social communication Language/communication Play/imitation |

3.03 (0.64) | 3.80 (0.39) | 11.87 (p = 0.007) |

| Manages Interactions | Sets up environment to facilitate regulation Modulates child's affect, arousal, and attention Overall attunement/engagement |

3.30 (0.62) | 4.13 (0.32) | 11.87 (p = 0.007) |

| Overall Fidelity | Includes all categories | 3.13 (0.51) | 3.77 (0.33) | 22.57 (p = 0.001) |

The average fidelity score across parents for pre- and post-training in each of seven strategies. Individual techniques included in each of the strategies and absolute t-score values are also listed.

Table 3.

Parent satisfaction survey results.

| Question | Meana (SD) | Range (minimum–maximum) |

|---|---|---|

| This is an acceptable intervention for my child's social communication skills | 6.6 (0.52) | 6–7 |

| I enjoyed this program | 6.8 (0.42) | 6–7 |

| I would suggest the use of this intervention to other parents | 6.6 (0.70) | 5–7 |

| The parent coaching was clear, understandable, and helpful | 6.6 (0.52) | 6–7 |

| The amount of training and support I received was sufficient for me to learn the intervention strategies | 6.5 (0.71) | 5–7 |

| The trainers were knowledgeable | 6.8 (0.42) | 6–7 |

| The goals of the intervention are important to my child's functioning at home | 6.4 (0.84) | 5–7 |

| I use this intervention at home | 6.6 (0.52) | 6–7 |

| I understand how to use the techniques at home during everyday activities | 6.1 (0.88) | 5–7 |

| This intervention was a good way to teach social communication skills to my child | 6.6 (0.51) | 6–7 |

| I understand which skills my child was working on and why | 6.6 (0.52) | 6–7 |

| The homework assignments were clear and manageable | 6.2 (0.92) | 5–7 |

| The intervention was effective in teaching my child's social communication skills | 6.9 (0.32) | 6–7 |

| I feel my child improved her/his social engagement as a result of this program | 6.5 (0.71) | 5–7 |

| The intervention will produce lasting improvement in my child's social communication skills | 6.6 (0.52) | 6–7 |

| The intervention quickly improved my child's social communication skills | 6.3 (0.67) | 5–7 |

| Other behaviors related to social communication were also improved by the intervention | 6.2 (0.79) | 5–7 |

| Using the intervention not only improved my child's social communication skills at home but also in other settings (e.g. classroom, community) | 6.0 (1.33) | 4–7 |

| I use the intervention with my child regularly | 6.2 (0.92) | 5–7 |

SD: standard deviation.

The satisfaction survey items and the mean scores across parents for each item, as well as the range of scores reported.

Parents received the following instructions: A score of 1 indicates that you Strongly Disagree with the statement. A score of 7 indicates that you Strongly Agree with the statement. A score of 4 indicates you Neither Agree nor Disagree with the statement.

Parents reported Overall Satisfaction with the intervention as high (M = 6.46; SD = 0.41; range = 5.7–7, out of 7 possible). Parent responses in the interviews also supported that general satisfaction was very high; all parents indicated they “believed” in the approach. Results are described below based on the emergent interview themes related to the parent coaching process, impressions of the intervention, and impact of the intervention.

Parent coaching process

Acceptability of intervention and parent coaching format

Ratings on the survey items This is an acceptable intervention for my child's social communication skills (M = 6.6; SD = 0.52), I enjoyed this program (M = 6.8; SD = 0.42), and I would suggest the use of the intervention to other parents (M = 6.6; SD = 0.70) were all high, indicating strong parent buy-in and support for the intervention.

Parent interview responses expanded on the survey data. Specifically, parents reported “believing” in the parent coaching approach and feeling that their involvement in their child's intervention was important for child progress and their own feelings of empowerment. For example, one parent focused on her own need to participate:

It was incredibly useful … because we wanted to be involved … when we got his diagnosis, we didn't want to just lay down and just let someone else deal with it, we wanted to be part of it and do something and not just feel like we couldn't contribute. So that part for me was that most valuable, because even though he's not meeting with [the therapist] anymore, I know what he should be doing and I know what I can do to help. So for me it's the best.

Another parent focused on the importance of her involvement to support child progress:

I can get him to communicate more and teach him all day long instead of just, when the tutor's here … And I think he's made progress too, so now that I've seen it kind of works, I know that I have to keep using all the skills I've learned.

Active parent coaching as critical to intervention

Parents' ratings on survey items related to the coaching process utilized in Project ImPACT were high: Coaching was clear and helpful (M = 6.6; SD = 0.52) and The amount of training and support received was sufficient for me to learn the intervention strategies (M = 6.5; SD = 0.71).

In the interviews, parents reported that working with the therapist was one of the most useful aspects of the Project ImPACT program. Seeing the therapist model, the strategies and practice with feedback were identified as especially helpful. One parent captured the majority sentiment when she said,

the time that we spent together working in the therapy setting was great, because I could watch [the therapist] do the strategies and then she gave me time and real-time feedback on how to do things and then she'd always ask me how it was going.

When asked to elaborate on what it was like to receive the therapist's feedback, all parents reported that the feedback was helpful and contributed to the training being a positive experience. Many parents also appreciated therapists' suggestions regarding activities to strengthen their child's weaker skills. Suggestions from parents about the feedback from therapists included requests for greater tailoring of intervention strategies to child's individual abilities.

Similarly, parents' ratings on the survey item Therapist was knowledgeable were high (M = 6.8; SD = 0.42). They described confidence in the therapists' level of knowledge and ability to implement the intervention strategies. “It felt to me like she knew exactly what she was doing and I felt really comfortable that she was going to guide us in the right direction and she did a really good job.” Additionally, they reported a strong sense of support from the therapists. “She was never at a loss for an answer, so I didn't feel like she wouldn't know anything—anything we would have asked her she would have answered.”

Impressions of the intervention

Intervention considered feasible and useful

In survey responses, parents endorsed the item The goals of the intervention were important to my child's functioning at home (M = 6.4; SD = 0.84). While parents endorsed that they used the intervention at home (M = 6.6; SD = 0.52), the responses to whether they understood how to use the strategies during everyday activities were more moderate (M = 6.1; SD = 0.88).

In interviews, parents consistently highlighted the importance of their ability to integrate the approach into their daily lives. For example, one parent said,

I definitely like the fact that you're training the parents to use this in the day-to-day … I get home at 7:00, so when am I supposed to carve out 20 minutes to play with him? It's really hard. So just how you can do it, when you're feeding him, if it's the two minute increments you can be successful just doing that throughout the entire day.

However, one parent commented that the activities used in the clinical setting were not translating to daily routines at home or public family outings. She also noted that the materials (toys) included in the trainings were not interesting to her child and made it difficult to then take the techniques home.

The most useful component of the intervention identified by parents was learning to follow the child's lead (a developmental strategy). “I think that the most useful thing about the training was learning really how to follow your child's lead … And really follow them and to get down on their level and to maintain face to face contact.” They also felt successful at using this piece of the intervention. “I think I am much better able to follow her lead and to keep her engaged in a fun way in everyday activities.”

Although most parents rated the intervention highly on the item “This intervention is a good way to teach social communication skills to my child” (M = 6.6; SD = 0.51), some identified specific challenges in the interview. Challenges specific to the intervention included getting comfortable using the techniques and parent concerns that not all strategies were appropriate for their child's abilities. For example, one parent indicated that she found it “uncomfortable and frustrating” to target verbal communication with her nonverbal child.

Treatment planning process

Overall, parents reported liking the treatment planning process of conducting an assessment and developing goals for themselves and for their child. On the survey, they indicated that they understood which skills their child was working on and why (M = 6.6; SD = 0.52). In the interview, one parent described the goal development process saying, “it really set the stage for what we were going to work on, and what we were targeting. Baby steps, realistic goals.” Another said,

It was very helpful. We were able to talk about goal setting and see where he was at in terms of level of play and language and then we were able to review it at the end and see the progress he made.

Homework

Parents rated the survey item Homework was clear and manageable as moderate (M = 6.2; SD = 0.92) and parents' most critical comments about the intervention were related to homework. Specifically, a number of parents reported challenges finding time to practice the strategies and completing the homework and readings. Some also questioned the utility of the homework. One parent commented, “I didn't see a lot of value in the homework to be completely honest with you. I felt it was busy work, and if you see my book, you'll see it's hardly filled out.” Some parents commented that the handouts were confusing or redundant.

Logistics of the intervention format

Recommendations for improving the intervention generally addressed the logistical challenges reported. The most frequent requests surrounded increased flexibility in scheduling the therapy sessions, lengthening the session duration and improving the orientation to the intervention by including some background theory and before/after videos. Several parents also requested opportunities to meet other participating families as they go through the intervention.

Perceived effectiveness

On the survey, parents indicated strongly that the intervention was effective in teaching my child social communication skills (M = 6.9; SD = 0.32), my child improved her/his social/engagement as a result of the program (M = 6.5; SD = 0.71) and that they believed the intervention will produce lasting improvement in my child (M = 6.6; SD = 0.52). Scores were more moderate, in comparison, when asking about whether The intervention quickly improved my child's social communication skills (M = 6.3; SD = 0.67), Other behaviors related to social communication were also improved by the intervention (M = 6.2; SD = 0.79), and Using the intervention has improved my child's social communication skills not only at home but also in other settings (e.g. classroom, community) (M = 6.0; SD = 1.33). This final concern about generalization was consistent with one parent's comment that she could use, “more help in everyday activities (eating, playing outside, and getting dressed).”

Improved child social communication

Examples from parents of children with varying levels of communication abilities illustrate the effect of the intervention on both verbal and nonverbal communication and the spontaneous nature of both communication and play skills. “His communication skills have improved dramatically; he's using a ton of word approximations.” and “He's signing more than he was, and he's doing it spontaneously. So he'll walk up to me now and sign that he's hungry, whereas he would never do that before.” Another parent also talked about nonverbal skills, saying

… halfway through the training he started … grabbing my hand and wanting me to go places and play with him. Before he used to kind of wander around the room by himself and not kind of include us. Like he didn't even know we were there. Now he knows we're there and he wants to play with us, and he actually wants to play with us a lot.

Changes were reported in receptive communication skills as well. One parent describes her child's responsiveness: “A lot more eye contact, definitely responding to words, responding to his name, some directions he can respond to.” Additionally, some parents specifically mentioned increased connections with their children. For example, after describing significant improvements in communication and play, one parent indicated

We owe a lot to the program just in being able to know how to play with our son and engage him and interact with him and through that, a definite bond has formed that I did not feel that I had with my son before we started the program.

Many parents mentioned that seeing their child's progress led to their ongoing use of the strategies after they had completed the program. “[My son] made a significant amount of progress and we're using the strategies with him now and we're seeing continued progress now.” This may have led to some differences in how parents ranked use of the intervention regularly. Overall, the mean score was 6.2; however, three parents gave this item a 5, indicating some limited use.

Reduced parent stress

During the course of the interview, two-thirds of the parents mentioned that they felt reduced stress after the intervention. Parents who reported decreased stress often attributed to their increased comfort level in interacting with their child in ways that may facilitate development:

In the beginning when you get that diagnosis and you don't know a lot about it and you don't know what you can do and it's really scary. And after you go through the training you just feel like you can handle this. And there are things you can do to contribute. So I think that helps with the stress.

A reduction in behavioral problems as child skills increased also seemed to contribute to reductions in perceived stress for families. “I think it's [stress] decreased actually. Because I feel more comfortable with my expectations for what he should be doing and what he is doing. I just feel more comfortable about that.”

Discussion

Findings in this study are unique in that we included the direct perspective of the parent experience using multiple methods (parent satisfaction assessment and an in-depth interview). Results of this study provide preliminary support for the successful implementation of a selected parent-mediated NDBI intervention that was applied using a community-partnered approach. Specifically, findings from both qualitative and quantitative data indicate that parents had very positive perceptions of the feasibility, utility, and effectiveness of Project ImPACT when implemented by community EI providers. Furthermore, observational data indicate that parents were able to learn and implement the Project ImPACT strategies in the relatively brief 12-session intervention period. This study represents a unique method for determining the feasibility of implementing an evidence-based, parent-implemented treatment program in community settings.

This study demonstrates that community-based participatory research (CBPR) may be one effective way to increase the fit and feasibility of an evidence-based treatment for use in community practice. Although there are examples of research–community partnerships to implement evidence-based practices in community-based mental health services (Chorpita et al., 2002; Chorpita and Mueller, 2008; Southam-Gerow et al., 2009; Wells et al., 2004), this is the one of the first efforts to use a partnership model in the field of EI for ASD. Our earlier work describing partnership development demonstrated the proximal effects of the partnership in terms of partnership synergy (i.e. adhered to the participatory research elements outlined by Naylor et al. (2002) and had strong collaborative functioning), productivity (i.e. attainment of all initial goals and the large number of tangible products targeting multiple audiences), and sustainment of the partnership over time (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2012). The current study provides further support for the CBPR implementation process by documenting positive family-related outcomes of the intervention. Community providers were able to successfully teach parents the intervention strategies. Additionally, parents report some reduced stress, increased feelings of competence and support, and an improved parent/child relationship. They also reported that the intervention benefited their child and all parents reported believing in the approach. Information from community providers and parents will be used to adapt the program further to increase fit and feasibility and without CBPR this type of feedback may have been very limited. While these results are primarily qualitative, they provide preliminary support that can be confirmed in a larger study.

Understanding parent perspectives on intervention is crucial to support use and sustainment of an intervention and to ensure that the intervention does not negatively affect family well-being (Stahmer and Pellecchia, 2015). Unlike clinician-delivered interventions, the goal of parent-mediated intervention is for the child to benefit from continued, ongoing contact with the therapeutic strategies as implemented by the parent in their daily contact with the child. This can only occur if parents can learn the strategies and are willing to use them in an ongoing way. Attrition in parent-implemented intervention studies can be high, especially when low-resourced families are involved (Kasari et al., 2014) and highlights the challenges of developing parent-implemented interventions that are feasible and sustainable over time. Qualitative and quantitative data indicate that parents implemented the intervention well with relatively brief training and that they were willing to use the intervention at home. They discuss using the intervention outside of the “therapy hour” and implementing the intervention in daily routines, although some parents continued to find the translation to the home environment challenging. Studies of parent-implemented interventions in autism suggest that participation may be enhanced by targeting increasing self-efficacy (Solish and Perry, 2008) and improving confidence that the intervention will produce meaningful outcomes (Moore and Symons, 2011). Whether or not inclusion of reflective practice training for providers may have facilitated parent empowerment in this project will be examined more explicitly in future projects. Parents in this project reported feeling more confident in their skills as they saw improved communication and social skills in their children. These perceptions may increase the likelihood that parents will use these strategies at home.

Additionally, although children in this project were very young and some had not yet received a diagnosis of ASD, parents were still willing to attend treatment sessions, learned the strategies well, and saw improvement in the children at this very young age. This provides additional support that parent coaching interventions are acceptable and feasible to community participants, even at young ages. This is important because new research has indicated that beginning intervention very early, even before a diagnosis is made, may reduce later ASD symptoms (Rogers et al., 2014). However, this also raises policy issues around services for children who do not yet have a formal diagnosis. Through Part C of Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), EI services are provided to children. Some states will serve children “at risk,” but a large majority of states require significant delay or diagnosis before providing services. Because funders were included in our CBPR process, we were successful in obtaining public funding for a majority of families. This highlights the importance of addressing funding concerns of an intervention from the earliest stages of development. Additional data are needed on the long-term effects of early parent-implemented interventions to help guide funding and policy more broadly.

Although parents in this project could use the intervention and were satisfied with it, they also provided some comments that might suggest some modifications may make the intervention even more acceptable to very young children. For example, some parents reported frustration with a focus on verbal communication in their young, nonverbal children. Although we attempted to emphasize the importance of early gestures and vocalizations in the training, clearly more emphasis was needed for providers and families. The materials, because they were developed for older children, included many verbal examples and several of the lessons specifically focused on language production. Providing written materials for providers and parents that include developmentally appropriate intervention targets for very young children and an increased emphasis on how to use the strategies before children have words may facilitate use of the techniques and feelings of frustration for parents whose children are not talking.

Parent feedback gathered in the study indicates the need for improved support for parent use of the intervention at home and in the community. Both quantitative and qualitative data indicate that the current format of written homework questions does not seem beneficial to parents. The written questions are designed to help the parents apply the techniques at home, increase independence with the strategies, and increase the likelihood of practicing at home (Ingersoll and Dvortcsak, 2010). It is possible that these goals could be better addressed without the need for the written responses from parents, thus removing the impression of “busy work.” Rather than requiring written responses, therapists could increase focus on collaboratively creating a detailed, specific plan for when the parent will practice the intervention with their child and what specific tools from the intervention they will implement with their child. The therapist could follow-up with the parent during the following session to see how the specific plan went, what was successful, and what was challenging (the current content of the written questions). This focus on actionable, specific, collaborative planning with detailed follow-up is a well-established method to support behavior change in the adult learning and self-management literature (Kiesler, 1971; Lorig et al., 2013). Parent-mediated interventions, including Project ImPACT should consider adopting this type of thorough planning with the parent in order to improve the likelihood of at-home practice and thus ultimately increase parent independence with the use of the strategies.

Limitations

The most significant limitation of this study is the small number of participants. This leads to concerns regarding selection bias, family demographic representativeness, and generalizability of results. Families were recruited after seeking care at one of the participating community agencies and agreed to participate on a voluntary basis. It is possible these families were more likely to access services than families from other populations and were ready to access services due to concerns about their child's development. Future studies of parent-implemented interventions will need to solicit similar perspectives from families with a wider range of income, education, and cultural backgrounds to increase generalizability of the findings. It is possible, and even likely, that adaptations will need to be made based on family characteristics.

In addition, the providers in the current study worked at agencies that participated in the selection of the intervention to be implemented (through the BRIDGE Collaborative). Although the providers themselves were not involved in the intervention selection, it is possible that their agencies were more invested that usual community agencies in seeing the program succeed. Additionally, these providers were willing to participate in a research study and had high levels of education and experience relative to some Part C program providers. Parent satisfaction may differ in programs where providers have more limited expertise in working with young children.

Finally, although expert raters were trained to code fidelity of implementation with a high degree of reliability (80%) before coding project videos, ongoing reliability data are not available for parent videos. Coders were blind to time in treatment, however.

Conclusion

These results indicate that implementing Project ImPACT is feasible when community providers are trained to teach parents in usual care to use the strategies. With appropriate modifications, such as revising or reducing the homework assignments and adapting the materials to fit the development level of a younger population, the intervention has the potential to be successfully implemented on a much broader scale. The use of the CBPR method of implementation of the intervention appeared to facilitate use in community practice, and ongoing modifications based on these data may be more likely to support sustainment. Future research should directly compare this implementation model to other methods.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the BRIDGE Collaborative members in the development and implementation of this project. They would like to thank the children, families, and providers who participated. This work was conducted at the Child and Adolescent Services Research Center. Please note that Dr Stahmer was affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego and Rady Children's Hospital—San Diego at the time this work was completed.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) research grant: United States Public Health Service (USPHS) research grant 1R21MH083893-01A1 and the US Department of Education grant R324A140004. Additionally, Drs Stahmer and Brookman-Frazee are investigators with the Implementation Research Institute (IRI) at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis, through an award from the NIMH (R25MH080916).

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

References

- Aldred C, Green J, Adams C. A new social communication intervention for children with autism: pilot randomised controlled treatment study suggesting effectiveness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(8):1420–1430. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Hebbeler K, Scarborough A, et al. First experiences with early intervention: a national perspective. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):887–896. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy E, Brownell MT. Getting beyond the research to practice gap: researching against the grain. Teacher Education and Special Education. 2004;27:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bourque L, Fielder EP. How to Conduct Telephone Surveys. Vol. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Stahmer AC, Lewis K, et al. Building a research-community collaborative to improve community care for infants and toddlers at-risk for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;40(6):715–734. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buescher AV, Cidav Z, Knapp M, et al. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168(8):721–728. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortal Weekly Report (MMWR) 2014;63:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita B, Mueller C. Toward new models for research, community, an consumer partnerships: some guiding principles and an illustration. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15(2):144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita B, Yim LM, Donkervoet JC, et al. Toward large scale implementation of empirically supported treatments for children: a review and observations by the Hawaii Empirical Basis to Services Task Force. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(2):165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Coogle CG, Guerette AR, Hanline MF. Early intervention experiences of families of children with an autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative pilot study. Early Childhood Research & Practice. 2013;15(1) [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G. Research: early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(3):775–803. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):e17–e23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes A, Vismara L, Mercado C, et al. The impact of parent-delivered intervention on parents of very young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(2):353–365. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1874-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freuler AC, Baranek GT, Tashjian C, et al. Parent reflections of experiences of participating in a randomized controlled trial of a behavioral intervention for infants at risk of autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2013;18(5):519–528. doi: 10.1177/1362361313483928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hess KL, Morrier MJ, Heflin LJ, et al. Autism treatment survey: services received by children with autism spectrum disorders in public school classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(5):961–971. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0470-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K, Burns BJ, Kiser L, et al. Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(9):1179–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LN, Hepburn MS, Espiritu RC. To be or not to be… Evidence-based? Data Matters: An Evaluation Newsletter. 2003;6:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Hume KS, Bellini S, Pratt C. The usage and perceived outcomes of early intervention and early programs for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2005;25(4):195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B. Increasing generalizations through the use of parent-mediated interventions. In: Whalen C, editor. Real Life, Real Progress: A Practical Guide for Parents and Professional on Generalization for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Company; 2009. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B. Child and family outcomes for children with autism participating in the Teaching Social Community Curriculum. Paper presented at the International Meeting for Autism Research; San Diego, CA. 12–14 May 2011.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B, Dvortcsak A. Teaching Social Communication to Children with Autism: A Practitioner's Guide to Parent Training. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B, Dvortcsak A, Whalen C, et al. The effects of a developmental, social-pragmatic language intervention on rate of expressive language production in young children with autistic spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2005;20(4):213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B, Meyer K, Bonter N, et al. A comparison of developmental social-pragmatic and naturalistic behavioral interventions on language use and social engagement in children with autism. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2012;55(5):1301–1313. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/10-0345). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarbrink K, Knapp M. The economic impact of autism in Britain. Autism. 2001;5(1):7–22. doi: 10.1177/1362361301005001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;197(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser AP, Hancock TB, Nietfeld JP. The effects of parent-implemented enhanced milieu teaching on the social communication of children who have autism. Early Education and Development. 2000;11(4):423–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Lawton K, Shih W, et al. Caregiver-mediated intervention for low-resourced preschoolers with autism: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):e72–e79. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler CA. The Psychology of Commitment: Experiments Linking Behavior to Belief. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel LK, Bimbela A, Schreibman L. Collateral effects of parent training on family interactions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1996;26(3):347–359. doi: 10.1007/BF02172479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore PS, et al. Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):694–701. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Laurent DD, Plant K, et al. The components of action planning and their associations with behavior and health outcomes. Chronic Illness. 2013;10(1):50–59. doi: 10.1177/1742395313495572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton D. Measuring parent satisfaction with early childhood intervention programs. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 1994;14(1):26–48. [Google Scholar]

- Maglione MA, Gans D, Das L, et al. Nonmedical interventions for children with ASD: recommended guidelines and further research needs. Pediatrics. 2012;130(Suppl. 2):S169–S178. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0900O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney G, Perales F. Using relationship-focused intervention to enhance the social-emotional functioning of young children with autism spectrum disorders. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2003;23(2):77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C, Rossman G. Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moore TR, Symons FJ. Adherence to treatment in a behavioral intervention curriculum for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Modification. 2011;35(6):570–594. doi: 10.1177/0145445511418103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAMH Council. Blueprint for Change: Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Bethesda, MD: NIMH; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Educating Children with Autism. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Standards Project (NSP) National Standards Report. Randolph, MA: National Autism Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor PJ, Wharf-Higgins J, Blair L, et al. Evaluating the participatory process in a community-based heart health project. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(7):1173–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner M, Rayar M, Bashir N, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing pre-diagnosis autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-Targeted intervention with Ontario's autism intervention program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45:2833–2847. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MB, Jensen PS, Jaccard J, et al. Applying theory-driven approaches to understanding and modifying clinicians' behavior: what do we know? Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(3):342–348. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed S, Stahmer A, Suhrheinrich J, et al. Stimulus over-selectivity in typical development: implications for teaching children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(6):1249–1257. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers L, Vismara A, Wagner AL, et al. Autism treatment in the first year of life: a pilot study of infant start, a parent-implemented intervention for symptomatic infants. Journal of autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2014;44(12):2981–2995. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2202-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ. Empirically supported comprehensive treatments for young children with autism. Journal Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:168–179. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman L, Dawson G, Stahmer AC, et al. Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45(8):2411–2428. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz IS. Controversy or lack of consensus? Another way to examine treatment alternatives. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 1999;19(3):189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Solish A, Perry A. Parents' involvement in their children's behavioral intervention programs: parent and therapist perspectives. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2008;2(4):728–738. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon R, Van Egeren LA, Mahoney G, et al. PLAY Project Home Consultation intervention program for young children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2014;35(8):475–485. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow M, Hourigan S, Allin R. Adapting evidence-based mental health treatments in community settings: preliminary results from a partnership approach. Behavior Modification. 2009;33(1):82–103. doi: 10.1177/0145445508322624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer A. Teaching professionals and paraprofessionals to use pivotal response training: differences in training methods. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the California Association for Behavior Analysis; Dana Point, CA. 17–19 February 2005.2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer A, Gist K. The effects of an accelerated parent education program on technique mastery and child outcome. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2001;3(2):75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer A, Pellecchia M. Moving towards a more ecologically valid model of parent-implemented interventions in autism. Autism. 2015;19(3):259–261. doi: 10.1177/1362361314566739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer A, Collings NM, Palinkas LA. Early intervention practices for children with autism: descriptions from community providers. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2005;20(2):66–79. doi: 10.1177/10883576050200020301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer A, Rieth SR, Brookman-Frazee L, et al. Proximal and distal outcomes from use of research-community partnerships to adapt evidence based practices for community ASD providers. Paper presented at the 9th biennial conference on research innovations in early intervention; San Diego, CA. 20–22 February 2014.2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer A, Schreibman L, Cunningham AB. Towards a technology of treatment individualization for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Research. 2010;1380:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers JA, Hoffman L, Marquis J, et al. Relationship between parent satisfaction regarding partnerships with professionals and age of child. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2005;25(1):48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vismara LA, Young GS, Stahmer AC, et al. Dissemination of evidence-based practice: can we train therapists from a distance? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39(12):1636–1651. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0796-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KM, Miranda J, Bruce ML, et al. Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:955–963. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby AM, Prizant B. Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile: Manual. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Company; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby AM, Guthrie W, Woods J, et al. Parent-implemented social intervention for toddlers with autism: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):1084–1093. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willms DG, Best JA, Taylor DW, et al. A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1990;4(4):391–409. [Google Scholar]