Abstract

Background/Aims

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) allows removal of colorectal epithelial neoplasms en bloc regardless of size. Colorectal ESD is a difficult procedure because of technical difficulties and risks of complications. This study aimed to assess the relationship between ESD outcome and degree of submucosal fibrosis.

Methods

Patients with colorectal tumors undergoing ESD and their medical records were reviewed retrospectively. The degree of submucosal fibrosis was classified into three types. The relationship between ESD outcome and degree of submucosal fibrosis was analyzed.

Results

ESD was performed in 158 patients. Thirty-eight cases of F0 (no) fibrosis (24.1%) and 46 cases of F2 (severe) fibrosis (29.1%) were observed. Complete resection was achieved for 138 lesions (87.3%). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that submucosal invasion of tumor and histology of carcinoma were independent risk factors for F2 fibrosis. Severe fibrosis was an independent risk factor for incomplete resection.

Conclusions

Severe fibrosis is an important factor related to incomplete resection during colorectal ESD. In cases of severe fibrosis, the rate of complete resection was low even when ESD was performed by an experienced operator. Evaluation of submucosal fibrosis may be helpful to predict the submucosal invasion of tumors and technical difficulties in ESD.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasms, Endoscopic submucosal dissection, Submucosal fibrosis, Risk factors

INTRODUCTION

It is widely accepted that endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a standard treatment for node-negative gastric cancer.1,2,3 This technique permits tumors to be removed en bloc regardless of size, thus leading to precise histologic evaluation and a lower recurrence rate.1,2 Because of these advantages, ESD is also used for colorectal lesions. However, when ESD is used for colorectal lesions, it is necessary to thoroughly evaluate the anatomical and histological differences of the colon compared to the stomach. Many studies have reported that the thin wall, sparse muscle layer, and tortuous folds of the colorectum lead to a substantial risk of procedure-related perforation.3,4,5,6 In addition, severe peritonitis may develop due to intestinal bacteria and feces when perforation occurs.5,6 Despite these limitations, an increasing number of studies have recently reported that colorectal ESD appears to be an effective and safe technique to achieve complete en bloc resection.3,7,8 However, a higher possibility of complications was found to be associated with right-side location or large size tumors and the presence of submucosal fibrosis.9 Submucosal fibrosis develops because of inflammation and tumor infiltration, which are known to increase the rate of perforation and affect the success rate of en bloc resection.10 However, few studies have assessed the risk factors of submucosal fibrosis and the association of submucosal fibrosis with the outcome of colorectal ESD.11,12 Therefore, in this study, we aimed to assess the factors that may predict the presence of submucosal fibrosis and the association of the presence of fibrosis with the outcome of colorectal ESD.

METHODS

1. Patients

We retrospectively analyzed a total of 158 colorectal epithelial neoplasms in 158 consecutive patients who were treated with ESD in the Division of Gastroenterology at the Hanyang University Guri Hospital in South Korea from January 2008 to December 2013. The indications for ESD were as follows: (1) depth of invasion limited to the mucosa or submucosa with a noninvasive pattern on chromoendoscopy and (2) large tumors that were difficult to treat by en bloc endoscopic mucosal resection. Written informed consent was obtained before the procedure. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hanyang University Guri Hospital. Endoscopic tumor morphology was categorized according to the Paris endoscopic classification.13 Lateral spreading tumors (LST) were classified as granular type (LST-G) or nongranular type (LST-NG). Tumor locations were categorized as the right colon (cecum, ascending, and transverse colon), left colon (descending and sigmoid colon), and rectum. Using chromoendoscopy with 0.5% indigo carmine, all lesions were evaluated for pit patterns and classified according to the Kudo classification.14

2. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection

For bowel preparation, all patients were given 4 L of polyethylene glycol during the morning of the ESD procedure. In this study, a single-channel lower gastrointestinal endoscope (CF-H260AI; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or gastroscope (GF-H260; Olympus) was used. High-frequency generators (VIO300D; ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH, Tubingen, Germany) were also used. ESD was performed by two endoscopic specialists highly experienced at performing ESD. The patients were sedated with intravenous propofol (0.5 mg/kg), midazolam (0.1 mg/kg), and meperidine (25 mg) before the procedures. Cap-assisted colonoscopy (Disposable Distal Attachment, D-201-14304; Olympus) was performed and indigo carmine was sprayed to examine the tumor morphology and pit pattern of the lesion. A mixture of saline, glycerol, and diluted epinephrine (1:10,000) or 0.4% hyaluronic acid solution (Sigmavisc; Hyaltec, Bagnolet, France) was injected into the submucosal layer. Circumferential incisions were performed with a Flex knife (Olympus or Kachu Technology, Seoul, Korea) or Dual knife (Olympus). Submucosal injection was repeated to distinguish between muscles and submucosal layers. Finally, submucosal dissection was performed with a Flex knife and a Dual knife. A hemostatic forceps (Coagrasper; Olympus) was used to control visible nonbleeding vessels during submucosal dissection.

3. Definitions

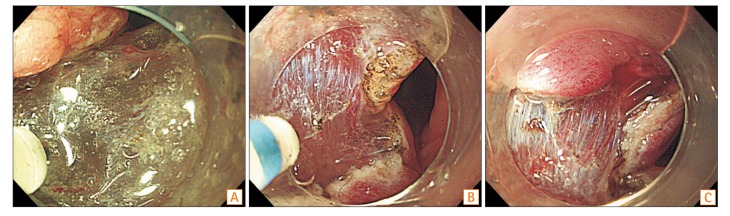

The degree of submucosal fibrosis was determined based on the findings observed at the time of submucosal local injection and classified into three groups (Fig. 1): F0 (no fibrosis), F1 (mild fibrosis), and F2 (severe fibrosis). F0 was defined as a transparent submucosal layer. F1 appeared as a white web-like structure in the transparent submucosal layer and F2 appeared as a white muscular-like structure without a transparent submucosal layer.12 Procedure time was defined as the time from incision with the knife to the complete removal of the lesion. The excised specimens were stained with H&E. Histologic diagnosis was classified according to the presence of adenocarcinoma and adenoma, depth of invasion, and the degree of fibrosis. The depth of submucosal invasion was examined by an expert pathologist (Y.H.O.) who was blinded to all clinical information. En bloc resection was regarded as resection resulting in removal of a single piece. Complete en bloc resection was considered when the tumor was removed as a single piece with tumor-free lateral and basal margins. Incomplete resection was defined as a specimen with the presence of tumor cells in the resected margins. Patients with cancer involvement of the vertical resection margin were referred to the surgical department for additional surgery.

Fig. 1. Degrees of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis in early colorectal tumors. (A) F0, no fibrosis, which manifests as a transparent submucosal layer. (B) F1, mild fibrosis, which appears as a white web-like structure in the transparent submucosal layer. (C) F2, severe fibrosis, which appears as a white muscular-like structure without a transparent submucosal layer.

4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P<0.05 was considered significant. The differences in the categorical variables were determined using Pearson chi-square test or Fisher exact test. For continuous variables, Student t-test was used when appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the effects of independent variables.

RESULTS

1. Colorectal Epithelial Neoplasm Treated with ESD

Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of 158 colorectal epithelial neoplasms treated with ESD. The median age of patients was 65.2 years; 91 patients were male. The median diameter of lesions was 25.9 mm. Tumor locations were as follows: 63 (39.6%) on the right colon, 52 (32.7%) on the left colon, and 43 (27.0%) on the rectum. Growth patterns were also evaluated; 56 polypoid, 68 LST-G, and 34 LST-NG were noted. Forty-one patients had tumors with pit pattern IV and 41 patients had tumors with pit pattern Vi.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Enrolled Patients.

| Variable | Value (n=158) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 65.2±10.1 (35–88) |

| Male:female | 91:67 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 25.9±10.7 (10–75) |

| Procedure time (min) | 63.4±38.3 (8–224) |

| Tumor location | |

| Right side | 63 (39.6) |

| Left side | 52 (32.7) |

| Rectum | 43 (27.0) |

| Growth pattern | |

| Polypoid | 56 (35.4) |

| LST-G | 68 (43.0) |

| LST-NG | 34 (21.5) |

| Pit pattern | |

| IIIS | 34 (21.5) |

| IIIL | 42 (26.6) |

| IV | 41 (25.9) |

| VI | 41 (25.9) |

| Histology | |

| Adenoma | |

| Low-grade | 31 (19.6) |

| High-grade | 60 (38.0) |

| Carcinoma | 67 (42.4) |

| Depth of invasion | |

| Mucosal | 134 (84.8) |

| Submucosal (µm) | 24 (16.1) |

| ≤1,000 | 16 (10.1) |

| >1,000 | 8 (5.1) |

| En bloc resection | 140 (88.6) |

| Complete resection | 138 (87.3) |

| Fibrosis | |

| F0 | 38 (24.1) |

| F1 | 74 (46.8) |

| F2 | 46 (29.1) |

| Perforation | 8 (5.1) |

| Additional surgery | 13 (8.2) |

Values are presented as mean±SD (range) or number (%).

LST-G, granular type of lateral spreading tumors; LST-NG, nongranular type of lateral spreading tumors; F0, no fibrosis; F1, mild fibrosis; F2, severe fibrosis.

A total of 67 neoplasms were histologically adenocarcinomas. Of the 67 cancers, there were 24 (16.1%) with submucosal invasion and eight (5.1%) with submucosal invasion more than 1,000 mm. Of the eight cancer patients with submucosal invasion more than 1,000 mm, six had tumors with pit pattern Vi, one had tumors with pit pattern IIIs, and one had tumors with pit pattern IV. F0 was observed in 38 lesions (24.1%) and F2 in 46 lesions (29.1%).

En bloc resection was achieved in 140 patients (88.6%) and complete resection with tumor-free lateral and basal resections. Among the seven patients without any additional surgery, six refused to receive further treatment. Perforation during ESD occurred in eight patients, and all were managed with conservative medical treatment after endoscopic closure with clipping.

2. Submucosal Fibrosis and Outcomes of ESD

Table 2 shows the clinicopathological characteristics according to the degree of fibrosis. In the F2 group, tumors were significantly larger compared to those in the F0 and F1 groups. The proportion with pit pattern Vi was higher in the F2 group. Carcinoma and submucosal invasion were found more often in F2 fibrosis. There was no significant difference in the location of tumors or procedure time between F0/F1 and F2 fibrosis groups. Perforation was found more often in F2 fibrosis. The complete resection rate in the F2 group was 63.0%, which was significantly lower than that in the F0 and F1 groups combined (97.3%). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the presence of submucosal invasion and that of carcinoma were independent predictors of F2 severe fibrosis (Table 3).

Table 2. Clinicopathological Characteristics with Respect to Degree of Submucosal Fibrosis.

| Variable | F0/F1 (n=112) | F2 (n=46) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 65.0±9.6 | 65.4±11.1 | 0.200 |

| Male:female | 68:44 | 23:23 | 0.220 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 24.1±8.9 | 30.1±13.3 | 0.010 |

| Procedure time (min) | 54.7±33.1 | 84.4±42.1 | 0.050 |

| Tumor location | 0.330 | ||

| Right side | 48 (42.9) | 15 (32.6) | |

| Left side | 37 (33.0) | 15 (32.6) | |

| Rectum | 27 (24.1) | 16 (34.8) | |

| Growth pattern | 0.080 | ||

| Polypoid | 38 (33.9) | 18 (39.1) | |

| LST-G | 53 (47.3) | 15 (32.6) | 0.490 |

| Homogeneous type | 25 (22.3) | 6 (13.0) | |

| Mixed nodular type | 28 (25.0) | 9 (19.6) | |

| LST-NG | 21 (18.6) | 13 (28.3) | |

| Pit pattern | 0.001 | ||

| IIIS | 28 (25.0) | 6 (13.0) | |

| IIIL | 34 (30.4) | 8 (17.4) | |

| IV | 31 (27.7) | 10 (21.7) | |

| VI | 19 (17.0) | 22 (47.8) | |

| Histology | 0.000 | ||

| Adenoma | 108 (96.4) | 26 (56.5) | |

| Carcinoma | 4 (3.6) | 20 (43.5) | |

| Depth of invasion | 0.000 | ||

| Mucosal | 77 (95.1) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Submucosal | 4 (4.9) | 10 (62.5) | |

| Depth (µm) | 1,098.5±918.3 | 2,049.1±993.2 | 0.090 |

| En bloc resection | 101 (90.2) | 39 (84.8) | 0.410 |

| Biopsy history | 64 (57.1) | 27 (58.7) | 0.860 |

| Polypoid tumor | 30 (26.8) | 11 (23.9) | 0.350 |

| LST-G and LST-NG | 34 (30.4) | 16 (34.8) | |

| Complete resection | 109 (97.3) | 29 (63.0) | 0.002 |

| Perforation | 3 (2.7) | 5 (10.9) | 0.020 |

| Immediate bleeding | 6 (5.4) | 4 (8.7) | 0.020 |

| Delayed bleeding | 1 (0.9) | 2 (4.3) | 0.004 |

| Additional surgery | 1 (0.9) | 12 (26.1) | 0.000 |

Values are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

F0, no fibrosis; F1, mild fibrosis; F2, severe fibrosis; LST-G, granular type of lateral spreading tumors; LST-NG, nongranular type of lateral spreading tumors.

Table 3. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Related to Submucosal Fibrosis.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor size | 1.01 (0.90–1.00) | 0.700 |

| Procedure time | 1.02 (1.00–1.10) | 0.100 |

| Pit pattern | 1.40 (0.90–2.10) | 0.120 |

| Carcinoma | 5.70 (2.00–16.40) | 0.001 |

| Submucosal invasion | 6.60 (1.30–32.50) | 0.005 |

| Complete resection | 1.96 (0.30–4.40) | 0.090 |

| Perforation | 4.68 (0.90–25.40) | 0.070 |

| Immediate bleeding | 1.21 (0.10–6.70) | 0.820 |

| Delayed bleeding | 1.24 (0.20–26.00) | 0.890 |

| Additional surgery | 2.92 (0.20–38.30) | 0.410 |

3. Risk Factors of Incomplete Resection and Additional Surgery

Comparisons between the complete resection and incomplete resection groups are shown in Table 4. There was no significant difference in tumor size (25.6 mm vs. 27.5 mm). The lesions with LST-NG and pit pattern Vi were more frequently observed in the incomplete resection group than in the complete resection group. In the incomplete resection group, 17 out of 20 cases (85.0%) were diagnosed as carcinoma, which was significantly higher than the carcinoma diagnosis rate in the complete resection group (50/138, 36.2%). The proportions of F2 fibrosis and submucosal invasion were significantly higher in the incomplete resection group than in the complete resection group. The mean depth of submucosal invasion was also higher in the incomplete resection group, but there was no significant difference. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that submucosal invasion and F2 fibrosis were significant contributors to incomplete resection related to ESD (Table 5). In addition, the presence of submucosal invasion (OR, 19.83; 95% CI, 3.5−112.8) and F2 fibrosis (OR, 10.17; 95% CI, 1.1−98.2) were independent risk factors for additional surgery (Table 6).

Table 4. Analysis of Risk Factors for Incomplete Resection.

| Variable | Complete resection (n=138) | Incomplete resection (n=20) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 65.6±9.6 | 62.5±12.8 | 0.320 |

| Male:female | 82:56 | 9:11 | 0.240 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 25.6±10.0 | 27.5±14.7 | 0.500 |

| Procedure time (min) | 62.5±37.0 | 70.0±47.2 | 0.100 |

| Tumor location | 0.340 | ||

| Right side | 53 (38.4) | 10 (50.0) | |

| Left side | 85 (61.6) | 10 (50.0) | |

| Growth pattern | 0.290 | ||

| Polypoid | 50 (36.2) | 6 (30.0) | |

| LST-G | 61 (44.2) | 7 (35.0) | 0.490 |

| Homogeneous type | 26 (18.8) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Mixed nodular type | 35 (25.4) | 4 (20.0) | |

| LST-NG | 27 (19.6) | 7 (35.0) | |

| Pit pattern | 0.010 | ||

| IIIS | 31 (22.5) | 3 (15.0) | |

| IIIL | 40 (29.0) | 2 (10.0) | |

| IV | 37 (26.8) | 4 (20.0) | |

| VI | 30 (21.7) | 11 (55.0) | |

| Histology | 0.000 | ||

| Adenoma | 88 (63.8) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Carcinoma | 50 (36.2) | 17 (85.0) | |

| Depth of invasion | 0.000 | ||

| Mucosal | 128 (92.8) | 6 (30.0) | |

| More than submucosal | 10 (7.2) | 14 (70.0) | |

| Depth (µm) | 1,219.8±410.3 | 2,087.3±1,167.1 | 0.060 |

| Fibrosis | 0.000 | ||

| F0/F1 | 109 (79.0) | 3 (15.0) | |

| F2 | 29 (21.0) | 17 (85.0) | |

| Additional surgery | 2 (1.4) | 11 (84.6) | |

| Perforation | 8 (5.8) | 0 | 0.600 |

Values are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

LST-G, granular type of lateral spreading tumors; LST-NG, nongranular type of lateral spreading tumors; F0, no fibrosis; F1, mild fibrosis; F2, severe fibrosis.

Table 5. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Related to Incomplete Resection.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Pit pattern | 1.70 (0.30–3.50) | 0.400 |

| Carcinoma | 2.10 (0.30–13.90) | 0.440 |

| Submucosal invasion | 11.50 (3.20–41.10) | <0.001 |

| Severe fibrosis | 8.09 (1.90–34.20) | 0.004 |

Table 6. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Related to Additional Surgery.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor size | 1.18 (1.00–1.90) | 0.080 |

| Procedure time | 0.97 (0.90–1.40) | 0.130 |

| Severe fibrosis | 10.17 (1.10–98.20) | 0.045 |

| Submucosal invasion | 19.83 (3.50–112.80) | 0.001 |

DISCUSSION

In this clinical study, we aimed to determine whether there are any factors that may predict the degree of submucosal fibrosis during colorectal ESD while also evaluating factors related to incomplete resection. Factors that may predict the degree of submucosal fibrosis are tumor size, histology, depth of invasion, and pit pattern. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that histology of carcinoma and presence of submucosal invasion were significantly related to submucosal fibrosis. In addition, the presence of submucosal invasion and severe fibrosis were associated with low complete resection rates.

Similar to our results, a previous study has reported that the presence of fibrosis was associated with difficult procedures and low complete resection rates during colorectal ESD.12,15 When the degree of fibrosis was assessed, F2 fibrosis was associated with this outcome.12 However, the previous study was not able to demonstrate the risk factors for severe submucosal fibrosis. In the present study, we evaluated the risk factors for severe fibrosis, and the results from the multivariate analysis showed that the presence of submucosal invasion is one of the predictive factors. In addition, we confirmed that the presence of submucosal invasion and severe fibrosis are predictive factors for incomplete resection and additional surgery.

A recent study has reported that adenocarcinoma is a predictive factor for submucosal fibrosis during gastric ESD.16 In our study, the group diagnosed with cancer demonstrated much more severe fibrosis of F2 compared to the adenoma group. In addition, histology of carcinoma was one of the risk factors for severe submucosal fibrosis.

Several previous studies have demonstrated that a right-side tumor is a significant risk factor for incomplete resection.9,17 The right colon is more challenging to manage compared to the left colon because of several factors such as severe peristalsis and high degree of technical difficulties. The authors explained that these are reasons why the tumor on the right colon was a risk factor for incomplete resection. However, previous studies did not evaluate the procedure duration as a confounding factor and overlooked the fact that the long duration of the procedure was related to fatigue, thereby affecting ESD outcome. The present study showed that there was no association between incomplete resection and location of tumor. Several prior studies have reported that history of biopsy is a risk factor for submucosal fibrosis.10,18 However, in our study, history of biopsy was not associated with severe submucosal fibrosis in the multivariate analysis.

A previous study reported that there was a higher proportion of LST-G and nodular mixed types in the severe fibrosis group, but that there was no difference in pit patterns.12 In addition, through the results of the univariate analysis, we revealed that LST-NG and Vi pit pattern were related to the presence of severe fibrosis. Although it is difficult to predict the presence of F2 severe fibrosis before the procedure, we suggest that careful observation of the size, growth pattern, and pit pattern of the lesions could lead to prediction of the presence of severe fibrosis. Further studies evaluating the predictive factors for F2 fibrosis before the procedure are necessary.

The perforation rate in this study was approximately 5%, which is similar to that found in previous studies. Many studies have suggested a wide range of perforation rates ranging from 1.4% to 14%.7,8,9,19,20 In cases with accompanying fibrosis, the perforation rate was significantly higher compared to those without fibrosis. This is because the tumor may not be elevated after submucosal injection in cases with accompanying fibrosis and the dissection margin may not be adequately secured for safe and complete dissection.9,18,21 Our study confirmed the association between fibrosis and perforation. However, in cases of perforation, patients under inappropriate sedation might be uncontrolled due to unexpected noncooperation during the procedure. Although successful ESD is not guaranteed when the tumor size is large with accompanying fibrosis, the procedure appears to be affected by the presence of fatigue of the endoscopist, appropriate sedation, patient control, and any other extrinsic factors.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective study that enrolled a limited number of cases from a single center. Second, there was a higher proportion of presence of fibrosis in our study than in recent studies. This might be because we have not assessed the presence of fibrosis, but rather the degree of fibrosis. In the previous study, absence of careful observation of fibrosis could have led to ignorance of mild fibrosis, and severe fibrosis was less likely to be missed.9,21 Third, we did not evaluate the relationship between endoscopic and histologic classifications of submucosal fibrosis. Also, we determined the degree of submucosal fibrosis based on endoscopic images and medical records in a retrospective manner. It is doubtful that endoscopic assessment is an objective measure of submucosal fibrosis. However, a previous study that managed to assess the relationship between the two suggested that the degree of submucosal fibrosis based on endoscopic findings was correlated with histologic fibrosis.16 We assumed that this fact could also be applied to this study.

In conclusion, when the degree of submucosal fibrosis is assessed during the colorectal ESD procedure, the presence of F2 severe fibrosis and the histology of carcinoma are significant risk factors for incomplete resection and additional surgery. Therefore, whenever submucosal invasion or severe fibrosis is suspected, considerable effort is needed to avoid incomplete resection. If such a difficult case is evident, then early surgical intervention should be considered instead of proceeding with colorectal ESD.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2011-0010841).

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009;58:331–336. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.165381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung IK, Lee JH, Lee SH, et al. Therapeutic outcomes in 1000 cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: Korean ESD Study Group multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1228–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niimi K, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal epithelial neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2010;42:723–729. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka S, Oka S, Chayama K. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: present status and future perspective, including its differentiation from endoscopic mucosal resection. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:641–651. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Nakamura M, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal epithelial neoplasia. Endoscopy. 2006;38:493–497. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang MY, Cho JW, Oh WG, et al. A case of pneumorrhachis and pneumoscrotum following colon endoscopic submucosal dissection. Intest Res. 2013;11:208–212. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Repici A, Hassan C, De Paula Pessoa D, et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia: a systematic review. Endoscopy. 2012;44:137–150. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamegai Y, Saito Y, Masaki N, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: a safe technique for colorectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2007;39:418–422. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isomoto H, Nishiyama H, Yamaguchi N, et al. Clinicopathological factors associated with clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal epithelial neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2009;41:679–683. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu K, Sano Y, Kato S, et al. Hazards of endoscopic biopsy for flat adenoma before endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1324–1327. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2781-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi N, Tanaka S, Nishiyama S, et al. Predictors of incomplete resection and perforation associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumoto A, Tanaka S, Oba S, et al. Outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors accompanied by fibrosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1329–1337. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.495416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(6 Suppl):S3–S43. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka S, Oka S, Hirata M, Yoshida S, Kaneko I, Chayama K. Pit pattern diagnosis for colorectal neoplasia using narrow band imaging magnification. Dig Endosc. 2006;18:S52–S56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato K, Ito S, Kitagawa T, et al. Factors affecting the technical difficulty and clinical outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2959–2965. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3558-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeong JY, Oh YH, Yu YH, et al. Does submucosal fibrosis affect the results of endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric tumors? Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishiyama H, Isomoto H, Yamaguchi N, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal epithelial neoplasms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:161–168. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b78cb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han KS, Sohn DK, Choi DH, et al. Prolongation of the period between biopsy and EMR can influence the nonlifting sign in endoscopically resectable colorectal cancers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka S, Oka S, Kaneko I, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia: possibility of standardization. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito Y, Uraoka T, Matsuda T, et al. Endoscopic treatment of large superficial colorectal tumors: a case series of 200 endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim ES, Cho KB, Park KS, et al. Factors predictive of perforation during endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of colorectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2011;43:573–578. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]