Abstract

The aim of this study was to find the frequency of various oral mucosal lesions in relation to age, sex, site and associated addiction habits. This retrospective study was done in tertiary care centre including 1280 patients of oral mucosal lesions. Clinical findings and detailed history of their addiction habits with frequency and duration was noted from the existing data. Cytological and histopathological diagnosis of various lesions was recorded to conclude diagnosis. The most common lesion in this study was found to be aphthous ulcers (44.5 %), followed by leukoplakia (12.9 %). The most common site of involvement was tongue in aphthous ulcers and buccal mucosa in leukoplakia. In the present study 66.46 % cases were non malignant, 21.2 % cases were premalignant and the remaining 11.9 % cases were found to be malignant. Oral lesions are common finding in patients presenting to ENT OPD. Aphthous ulcers are common oral lesions. A patient with oral mucosal lesion should be examined for dietary deficiency, systemic disease or premalignant state with simultaneous counseling to quit addiction.

Keywords: Aphthous ulcers, Premalignant lesions, Addiction habits, Histopathology

Introduction

Oral cavity can be considered as a gateway into the digestive system. The mucous membrane of the oral cavity has been looked upon as mirroring the general health.

Oral mucosal conditions and diseases may be caused by local causes (bacterial or viral), systemic diseases (metabolic or immunologic), drug related reactions, or lifestyle factors such as consumption of tobacco, betel quid or alcohol [1]. Oral lesions can cause discomfort or pain that interferes with mastication, swallowing, and speech, and they can produce symptoms such as halitosis, xerostomia, or oral dysesthesia, which interfere with daily social activities [2]. Different oral diseases, may be in the form of swelling (benign or malignant), or a mucosal or ulcerative lesion (pre-malignant or malignant), so the knowledge of all the pathological conditions of the oral cavity is mandatory for their successful treatment and management A premalignant lesion is like a smoldering volcano, which if not taken care of, may erupt, often with disastrous consequences. Oral cancer is the sixth most common cancer in the world [3–5]. Oral cancers are one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide and constitute a major health problem in developing countries, representing the leading cause of death. Although representing 2–4 % of the malignancies in the West, this carcinoma accounts for almost 40 % of all the cancers in the Indian subcontinent [3]. The present study is done to evaluate the prevalence of oral mucosal lesions, their incidence and spectrum of premalignant and malignant lesion of the oral cavity and their possible associations with respect to age, gender and habits.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective study of clinical records of the patients with oral mucosal lesions attending ENT OPD of tertiary care hospital in central India from April 2009 to 2014.

Eligibility Criteria

All the cases of oral mucosal lesion were taken in the study excluding patients with trismus, post operative head & neck malignancies & post chemo radiations.

Study Design

The study included 1280 patients of oral mucosal lesions who presented in ENT OPD over a period of 5 years. The case notes, of all the patients with oral mucosal lesions were retrieved & those who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. Subsequently, proforma was designed to collect detailed history of all the patients regarding demographic profile, occupation, chief complaints, presenting illness, history of various types of addictions like tobacco chewing, smoking, gutkha, betel nut & alcohol, dietary habits and their pattern (veg., non veg., mixed & fasting, and infrequent meals) were noted.

The details of the clinical examination were entered in the proforma which included mouth opening, oro-dental hygiene, site, size, number & other particulars of the lesion. Final diagnosis was concluded on the basis of clinical criteria, scrapings, cytology & histopathological examinations of the cases.

Results

In our study, aphthous ulcer was found to be the most common mucosal lesion (44.5 %), followed by leukoplakia (12.9 %) and oral lichen planus (8.4 %) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of various oral mucosal lesions in the study subjects

| Lesions | Frequency (n = 1280) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Aphthous ulcer | 570 | 44.5 |

| Leukoplakia | 166 | 12.9 |

| Oral lichen planus | 108 | 8.4 |

| Well differentiated SCC | 90 | 7 |

| Geographical tongue | 45 | 3.5 |

| Oral candidiasis | 45 | 3.5 |

| Mucocele | 45 | 3.5 |

| Moderately differentiated SCC | 46 | 3.59 |

| Erythroleukoplakia | 84 | 6.5 |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | 10 | 0.78 |

| Pyogenic granuloma | 20 | 1.5 |

| Squamous epithelial dysplasia | 23 | 1.8 |

| Verrucous Ca | 18 | 1.4 |

| Traumatic ulcer | 10 | 0.78 |

Most of the patients (54.7 %) of aphthous ulcer were in younger age group (21–40 years) whereas leukoplakia and oral lichen planus (16.7 % each) were found in older age group (61–80 years). Patients of aphthous ulcer presented mainly with odynophagia (71.2 %) and burning sensation in throat (57.1 %). Aphthous ulcers had more predilections for females (50 %) while leukoplakia (13.6 %) and oral lichen planus (8.6 %) for males, probably due to addiction habits.

In the present study most common site of oral lesion was buccal mucosa (29 %) followed by tongue (24 %). Aphthous ulcers most commonly involved tongue (10 %) while leukoplakia (7 %) and oral lichen planus (6 %) involved buccal mucosa mostly. Aphthous ulcer was the most common oral mucosal lesion found to be associated with other systemic diseases (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of systemic diseases with oral mucosal lesions

| Systemic disease | Oral lesion |

|---|---|

| Hansens disease | Aphthous ulcer |

| Hand, foot, mouth disease | Aphthous ulcer |

| Psoriasis | Geographic tongue |

| SLE | Aphthous ulcer |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | Aphthous ulcer |

| Steven Johnson syndrome | Aphthous ulcer |

| HIV | Aphthous ulcer |

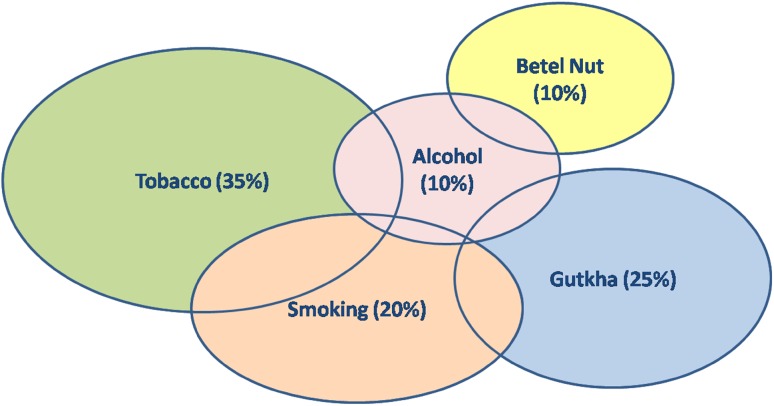

Majority of patients who presented with oral mucosal lesions had association with addiction (68 %) (Fig. 1). Mucosal lesions were mostly associated with smokeless form of tobacco (Fig. 2), which includes tobacco chewing (35 %), gutkha (25 %) and betal nut chewing (10 %), as compared to smoked form, which includes smoking (20 %).

Fig. 1.

Association of mucosal lesions with different addiction/habits

Fig. 2.

Association of smoked and smokeless tobacco with oral mucosal lesions

Premalignant conditions accounted for 21.2 % which included leukoplakia 12.9 %, erythroleukoplakia 6.5 %, squamous epithelial dysplasia 1.8 %. Malignant lesions were 11.9 % which included Well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma 7 %, Moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma 3.5 %, and verrucous carcinoma 1.4 %.

Discussion

Oral cavity being the most exposed part of the body is vulnerable to many diseases. Therefore it becomes important to examine oral cavity thoroughly so as to make an early diagnosis and timely intervention.

Our study concluded that aphthous ulcers are more common in younger age group and their prevalence decreases as age advances. This is also supported by the studies done by Davatchi et al. [6], who also found the prevalence of aphthous ulcers 11.7 % in age group of 15–29, 8.5 % in the age group of 30–44, 3.5 % in the age group of 45–59 and 1.5 % in the age group of >60 years.

Aphthous ulcers are more common in females (50 %) as compared to males (42 %) which is similar to the findings of Davatchi et al. [6] who found that the prevalence of aphthous ulcer in females was 14.9 % and in males was 10.3 %.

In the present study, majority of patients presented with aphthous ulcers, (44.5 %). This is in accordance with the study done by Patil et al. [7] who found the prevalence of aphthous ulcers 47.4 %, and the study done by Davatchi et al. [6]. The second most common lesion was found to be leukoplakia (12.9 %) (Fig. 3).

Fig.3.

Leukoplakia

Leukoplakia (7 %) and oral lichen planus (6 %) involved buccal mucosa while Aphthous ulcers most commonly involved tongue (10 %). Similar results were found by the study done by Mathew et al. [8] and Bokor Bratic [9] who found the involvement of buccal mucosa in 28.3 % cases. In this study, we also found association of systemic diseases with oral mucosal lesions, aphthous ulcer being the most common oral lesion.

In our study non malignant conditions constituted 66.46 % of cases, 21.2 % cases were premalignant and the remaining 11.9 % cases were found malignant (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Growth hard palate

Maximum patients with precancerous and cancerous lesions were addicted to tobacco chewing followed by smoking as compared to patients with non malignant lesions. This is in contrast to the study by Silverman et al. [10] (1984) who concluded that leukoplakia associated with a smoking habit seem to have less malignant potential than those not related to a smoking habit. Higher incidence of leukoplakia and oral lichen planus in males is attributed to the habits of tobacco chewing, smoking and alcohol.

Most of the patients, having the habit of chewing tobacco had the risk of developing premalignant or malignant lesions. The incidence of premalignant and malignant conditions were more common in the patients of low socio-economic background, with the habits of tobacco, smoking and alcohol and other contributing factors like lack of awareness, negligence and inappropriate medical guidance.

The commonest mucosal lesion in our study, aphthous ulcer, was seen mostly in individuals with vegetarian diet which may be due to dietary deficiency of vitamins. Among the individuals with non vegetarian diet, cause of aphthous ulcers could be attributed to reflux or regurgitation due to use of spices in ample amount. Our study also found synergistic role of addiction in causing various premalignant and malignant oral lesions.

Conclusion

Oral lesions are common finding in patients presenting to ENT OPD. In Indian population oral lesions are very common due to various systemic diseases, addictions and low socio-economic state. A patient with oral mucosal lesion therefore, should be examined thoroughly as early diagnosis of the precancerous and cancerous conditions is the key factor for their effective and timely management along with simultaneous counseling to quit addiction.

References

- 1.Harris CK, Warnakulasuriya KA, et al. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in alcohol misusers in south London. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.0904-2512.2004.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Triantos D. Intra-oral findings and general health conditions among institutionalized elderly in Greece. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:577–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iype EM, Pandey M, et al. Oral cancer among patients under the age of 35 years. J Postgrad Med. 2001;47(3):171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin DM, Pisani P, et al. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of eighteen major cancers. Int J Cancer. 1993;54:594–606. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910540413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4–5):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davatchi F, et al. The prevalence of oral aphthosis in a normal population in Iran: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. Arch Iran Med . 2008;11(2):207–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patil S, Doni B, et al. Prevalence of benign oral ulcerations in the Indian population. J Cranio Max Dis. 2014;3:2631. doi: 10.4103/2278-9588.130435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathew AL, et al. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in patients visiting a dental school in Southern India. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19(2):99. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.40461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bokor-Bratić M. The prevalence of precancerous oral lesions: oral leukoplakia. Arch Oncol. 2000;8(4):169–170. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverman S, Gorsky M, et al. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation: a follow up study of 257 patients. Cancer. 1984;53:563–568. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3<563::AID-CNCR2820530332>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]