Abstract

Objectives

To prospectively analyze the amount of alar flare, factors contributing to alar flare and efficacy of cinch suture as an adjunctive procedure for alar flare reduction.

Study Design

Thirty adult patients with vertical maxillary excess, who underwent Le Fort 1 impaction, were divided into 2 groups of 15 each. Alar cinch was performed as an adjunct procedure in group 2 patients and results were compared to group 1 which was the control group. Measurements were made on the patients and on 1:1 standardized photographs.

Results

Group 2 showed a near pre-operative alar position compared to group 1. The alar flare resulting from every millimeter of impaction was significantly less in group 2 compared to group 1.

Conclusion

Alar cinch suture restores the normal alar width by preventing the lateral drift of the naso-labial muscle and thereby reducing the postoperative nasal flare significantly.

Keywords: Alar flare, Le Fort 1 impaction, Alar cinch suture

Introduction

Le Fort 1 intrusion osteotomies are known to cause adverse effects on the oro-facial soft tissues such as broadening of the alar base, loss of vermillion show of the upper lip and down sloping of the commissure [1].

The Le Fort 1 osteotomy results in unpredictable soft tissue changes, which can be difficult to control because of considerable variation in their adaption. Adverse changes of the lip and nose including alar flaring, upturning of the nasal tip, and flattening of the lip/naso-labial region may occur, resulting in accentuation of the naso-labial groove, reduced vermillion exposure, thinning and lateral retraction of the lip, with down turning of the angle of mouth. The tip of the nose turns upwards, the naso-labial angle might increase and the maximal alar width increases. Soft tissue procedures on the nose, which can be performed simultaneously with a Le Fort 1 osteotomy, are the alar cinch suture, resection of the anterior nasal spine, wedge excision of the alar base, grinding of the paranasal area, and thinning of the columella [2].

Changes to the nose clearly occur after Le Fort 1 osteotomy (superior repositioning). There was a statistically significant increase in post operative interalar width and inter-nostril width with maxillary movement. There are various adjunctive procedures but no evidence to suggest the efficacy of each adjunctive procedure advocated to minimize nasal changes.

However, the alar flare, resulting as a consequence of superior repositioning of the maxilla, mars the objective of correcting VME and gummy smile. This study highlights the factors contributing to the phenomenon of alar flare as a consequence of Le Fort 1 intrusion and the significance of alar cinch suture.

Aims and Objectives

To assess the amount of alar flare.

To assess factors contributing to alar flare.

Efficacy of cinch suture as an adjunctive procedure.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion Criteria

Patients diagnosed with the following conditions:

Gummy smile.

Vertical maxillary excess (VME).

Exclusion Criteria

All orthognathic procedures not performed on maxilla.

Maxillary orthognathic procedures not involving superior repositioning of the maxilla.

Patients included in the above mentioned criteria, but who did not turn up for the follow up.

Thirty adult patients in the age group of 18–30 years with vertical maxillary excess (VME) were selected. Fifteen patients were subjected to endonasal intubation and underwent Le Fort 1 osteotomy with superior repositioning with no adjunctive procedure. Fifteen patients were subjected to endonasal intubation and underwent Le Fort 1 osteotomy with superior repositioning combined with cinch suturing. The alar cinch suturing was preceded by changing the naso-endotracheal tube to oral route. The technique of alar cinch suturing involved passing a 3–0 nylon suture through the naso-labial muscles on one side, passing it through a 2 mm hole created through the nasal spine and then anchoring it to the naso-labial muscles on the other side. The knot is based on the edge of the anterior nasal spine (ANS) bringing the naso-labial muscles closer to the nasal spine.

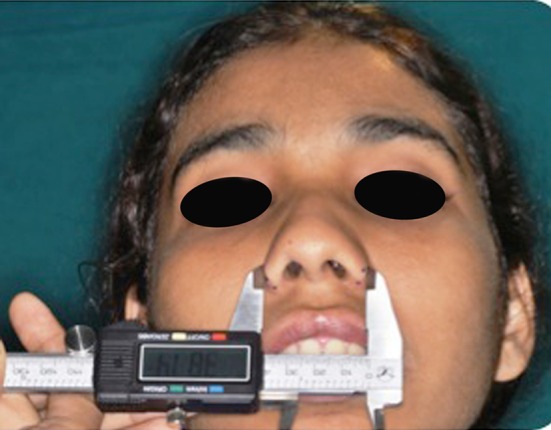

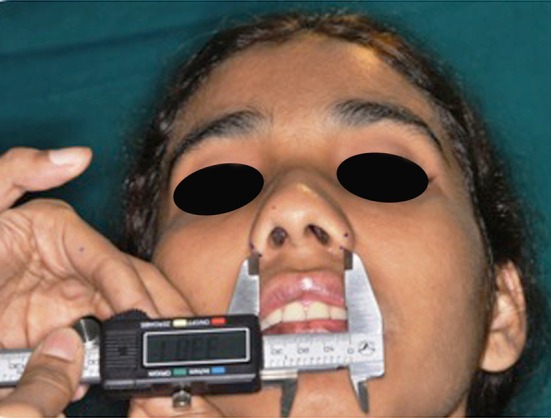

Preoperative interalar width was assessed by measuring the maximum convexity of the ala with the help of a vernier caliper (Fig. 1) and also by making two points at the center of the alar base (Figs. 2, 3) and measuring the same with the vernier caliper both on the patient and on the standardized photograph. The mean value of both the measurements was taken as pre-op interalar width. The same procedure was followed to measure postoperative inter-alar width after minimum period of 1 year. The results obtained were subjected to statistical analysis (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Points marked to measure the maximum convexity of the ala and alar base

Fig. 2.

Distance measured between the center of the maximum convexity of the ala using vernier caliper

Fig. 3.

Distance measured between the center of the alar bases using vernier caliper

Table 1.

Post-operative changes in alar flare following intrusion in 15 patients each of group 1 and group 2 (measurements in mm)

| Group 1 | Group 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrusion | Pre-op | Post-op | Diff | Intrusion | Pre-op | Post-op | Diff |

| 5 | 31 | 35 | 4 | 6 | 30 | 31.5 | 1.5 |

| 5.5 | 30 | 35 | 5 | 5 | 33.5 | 34.5 | 1 |

| 6 | 30 | 35 | 5 | 6 | 35.5 | 36.5 | 1 |

| 4.5 | 34 | 38.5 | 4.5 | 4 | 31.5 | 32 | 0.5 |

| 6 | 32 | 37 | 5 | 5 | 29 | 30 | 1 |

| 5.5 | 31 | 36 | 5 | 6 | 35 | 36 | 1 |

| 6 | 30 | 35.5 | 5.5 | 6 | 25 | 26 | 1 |

| 5 | 32 | 36.5 | 4.5 | 5 | 33 | 33.5 | 0.5 |

| 4 | 33 | 36 | 3 | 4 | 34 | 34.5 | 0.5 |

| 4.5 | 29 | 32.5 | 3.5 | 4 | 33 | 33.5 | 0.5 |

| 5.0 | 32 | 35 | 3 | 7 | 29 | 31 | 2 |

| 6.0 | 31 | 37 | 6 | 6 | 31 | 32 | 1 |

| 5.5 | 29 | 35 | 6 | 7 | 32 | 34 | 2 |

| 6.0 | 32 | 36 | 4 | 6 | 30 | 31.5 | 1.5 |

| 5.0 | 31 | 36 | 5 | 5 | 28 | 29 | 1 |

Based on the Pilot study of randomly selected 6 samples of group 2, the Pre test mean was 30.5, post test mean 32.1, SD pre test 2.9, SD post test 3.2, effect size 0.516, power 80 %, alpha error 5 %, based on 2 sided hypothesis sample calculated is 30.

Results

From the results derived from group 1, we could establish that for every 1 mm of intrusion there was 0.86 mm of alar flare. The results from group 2 indicate that the amount of nasal flare was dictated by the kind of adjunctive procedure and not by the amount of maxillary intrusion carried out. Group comparison using paired sample t test was found to be significant. Intergroup comparison was done by independent sample t test and it pronounced the following results:

Groups 1 and 2 Pre–Post Comparisons

Since p value was <0.05, we concluded that there is a statistically significant difference between pre and post values of groups 1 and 2 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation of pre–post operative comparison in groups 1 and 2 and Paired sample t test in groups 1 and 2 to determine p value

| Group (n = 15) | Mean | SD | 95 % confidence interval of the difference | Mean difference (pre–post) | p value (pre–post) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | ||||||

| Pre | 31.1333 | 1.40746 | Lower | Upper | 4.6 | <0.001 |

| Post | 35.7333 | 1.33452 | −5.12536 | −4.07464 | ||

| Group 2 | ||||||

| Pre | 31.3000 | 2.85857 | Lower | Upper | 1.06667 | <0.001 |

| Post | 32.37 | 2.75 | 0.79 | 1.34 | ||

Since p value was <0.05, we concluded that there is a statistically significant difference between post values of groups 1 and 2 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Levene’s test for equality of variances and t test for equality of means comparing post- operative values of group 1 and group 2

| Independent samples test | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levene’s test for equality of variances | t test for equality of means | ||||||||

| F | Sig. | T | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean difference | SE difference | 95 % confidence interval of the difference | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Equal variances assumed | 5.853 | 0.022 | 4.268 | 28 | <0.001 | 3.36667 | 0.78881 | 1.75086 | 4.98247 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 4.268 | 20.255 | 0.000 | 3.36667 | 0.78881 | 1.72256 | 5.01077 | ||

Regression Analysis

Regression Equation for Group 1

For every unit increase of intrusion there was 0.673 times increase in group 1 and 0.069 times increase in group 2 in the difference of alar flare position postoperatively recorded (Table 4).

Table 4.

Regression equation for groups 1 and 2

| Group | Regression analysis (difference=) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.983 + 0.673 * (Intrusion) |

| 2 | 0.444 + 0.069 * (Intrusion) |

The post-operative results in group 1, compared to pre-op, frontal and sub-nasal view, is depicted in Figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7 respectively. The post-operative results in group 2 compared to pre-op, frontal and sub-nasal view, is depicted in Figs. 8, 9, 10 and 11 respectively.

Fig. 4.

Pre-operative frontal view of a group 1 patient

Fig. 5.

Pre-operative sub-nasal view of group 1 patient

Fig. 6.

Post-operative frontal view of a group 1 patient

Fig. 7.

Post-operative sub-nasal view of group 1 patient

Fig. 8.

Pre-operative frontal view of a group 2 patient

Fig. 9.

Pre-operative sub-nasal view of group 2 patient

Fig. 10.

Post-operative sub-nasal view of group 2 patient

Fig. 11.

Post-operative frontal view of a group 2 patient

Discussion

Many studies have reported secondary morphological changes in the nose, including alar flaring after a Le Fort 1 osteotomy. The changes might be advantageous for patients with a narrow nose, but they can have a negative effect on the overall esthetics of the face in those with a wide nasal width [3].

Post surgical widening of the alar base after the maxillary Le Fort 1 procedure may be a favorable outcome in a patient with vertical maxillary hyperplasia and thin slit-like nares. However, if a wide preoperative alar base is present, these same changes become undesirable, especially with anterior or superior repositioning of the maxilla. Bell and Profit suggested that at time of preoperative assessment, patients with a wide nose be warned that a rhinoplasty may be indicated in the near future [4].

During Le Fort 1 osteotomy with superior repositioning of the maxilla, we observed that there was a reduction in the depth of the nasal aperture. This reduction in the depth of the nasal aperture does not provide adequate space for the alar base to occupy. This compromised space culminates in the naso-labial muscles being pushed laterally and thereby causing an increase in the inter-alar width resulting in post-operative nasal flare. Nasal widening, which is almost always observed after maxillary osteotomies, is only partially dependent on the amount of skeletal movement. The amount of subperiosteal dissection performed, which involves the total surface of the maxilla, seems to play a major role. Indeed, periosteal elevation disinserts the facial muscles from the naso-labial area and the anterior nasal spine. Other contributing factors include detachment of muscle insertion from its origin and the muscle tends to reattach at a shortened length because of contraction. This lateral retraction results in flaring, widening and elevation of the base of the nose, which is frequently not symmetric [5].

Maurice [6] describes important information stating that rotation of the palate does have significant effect on the soft tissue of the naso-labial region, also stating that changes in the lateral position of the pyriform aperture have significant effect on the soft tissue of the nasal base.

Even though the sample size is 30, the power of the study is 80 %, in relation to the power analysis based on the pilot study wherein 6 samples were randomly selected from group 2. This adds to the significance of the study.

We also observed that resection of the base of the nasal septum while superiorly repositioning the maxilla reduces the height of the nasal septum thereby losing the tip projection and contributing to alar flare. These alterations in the skeletal anatomy cause undesirable soft tissue response, which more often is clinically unacceptable.

Different movements of the maxilla have distinct effects on the nasal morphology. Superior repositioning of the maxilla causes elevation of the nasal tip, widening of the alar bases, and a decrease in the naso-labial angle [4]. According to a study conducted by Harvey Rosen, increase in alar rim width accompany superior and anterior repositioning of the maxilla [7]. Guymoon et al. [8] suggested that patients undergoing maxillary osteotomy with superior repositioning without an adjuvant procedure showed a mean increase in the interalar width by 10.75 % compared to patients with an adjuvant procedure where the mean increase was 2.89 %. In our study we observed that for every unit increase in the intrusion there is 0.673 times increase in the difference of alar flare position in group I patients and 0.069 times increase in the difference of alar flare position in group 2.

Several methods can be found in the literature and can be used in combination with each other: alar base cinch suture [9], partial or total removal of the anterior nasal spine in combination with an alar base cinch suture [6], V–Y closure of the wound in combination with a suture through the Muscularis Nasalis [10].

Westermark et al. [11] described the effect of an alar base suture in an attempt to gain control of the alar base flaring associated with maxillary advancement and/or maxillary impaction. The suture did reduce alar flaring but it also increased the naso-labial angle. The suture did not significantly influence nasal tip projection. Our study confers these findings to some extent.

Howley et al. [9] using a three-dimensional imaging system on 28 patients concluded that the alar suture confers little benefit in controlling the width of the alar base of the nose after Le Fort 1 osteotomy. They also suggested that a modified cinch suture may result in greater stability. Our results showed a better stability in group 2 attributed to the method of suturing the nasolabial muscle to ANS that we follow.

Shoji et al. [12] reported a modified technique for the placement of symmetrical cinch sutures after switching from a nasal to an oral endotracheal tube. In 30 patients they found that the suture did not alter the width of the alar base even after 1 year followup, but the nasolabial angle and projection of the tip increased significantly. In our study, we changed the naso-endotracheal tube to oral route just before the alar cinch suture was placed, however we got a better stable result in 1 year follow-up compared to the above mentioned study, which we attribute to passing the suture through the ANS.

Stewart and Edler [13] investigated the efficacy and stability of the alar base cinch suture by measuring nasal width in 36 patients before, during, and 12 months after, bimaxillary surgery with submental intubation. The use of submental intubation facilitated accurate measurement of the changes in nasal width produced by the osteotomy and the cinch suture. Their study concluded that a mean increase in the width of the base of the nose of 3.0 mm, 9 % (right and left alar points, al–al) and 3.6 mm, 11 % (right and left alar curvature points, ac–ac) after the osteotomy intra-operatively and that the cinch suture produced a reduction in these increases of 1.6 mm, 53 % (al–al), and 2.1 mm, 58 % (ac–ac). We observed that there was a lateral drift in the naso-labial musculature immediately after the incision and also after osteotomy thereby increasing the flare. We also noticed cinch suturing was effective in mitigating the alar flare increase following the intrusion. In our study the Regression analysis clearly suggested that the there is a significant reduction in the alar flare in group 2 compared to group 1.

Conclusion

We conclude that Le Fort 1 osteotomy (superior repositioning) leads to a widening of alar region of the nose, especially the alar base. Alar cinch suture restores the normal alar width by preventing the lateral drift of the naso-labial muscle and thereby reducing the postoperative nasal flare significantly.

The alar cinch suture brought in a significant reduction in alar flare when compared to group 1 where superior reposition was done without any adjuvant procedure especially when the suture is passed through the anterior nasal spine. It is a simple procedure that minimizes the option of a second surgery.

Cinch suture as an adjuvant procedure does not eliminate post-operative alar flare completely because it does not address the other contributing factors like the loss of pyriform depth and septal resection, which needs further evaluation.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation is extended to Mrs. Neevan D’Souza, M.Sc Biostatistics, Assistant Professor, Yenepoya Research Center, Yenepoya University, Ms. Soumya B. Shetty, M.Sc Biostatistics, Lecturer/Biostats, Department of Community Medicine, Yenepoya Medical College, Yenepoya University and Dr. Vinayak Kamath, Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health Dentistry, A. B. Shetty Memorial College of Dental Sciences, NITTE University for support in statistical analysis.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Muradin MSM, Seubring K, Stoelinga PJW, van der Bilt A, Koole R, Rosenberg AJWP. A prospective study on the effect of modified alar cinch sutures and VY closure versus simple closing sutures on nasolabial changes after Le Fort I intrusion and advancement osteotomies. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(3):870–876. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg Marvick A, Muradin SM, van der Bilt A. Nasolabial esthetics after Le Fort I osteotomy and VY closure: a statistical evaluation. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg. 2002;17(1):29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chunga C, Leeb Y, Parkc KH, Parkd SH, Parke YC, Kimf KH. Nasal changes after surgical correction of skeletal correction of skeletal Class III malocclusion in Koreans. Angle Orthod. 2008;78(3):427–432. doi: 10.2319/041207-186.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miloro M, Ghali GE, Larsen P, Waite P. Peterson’s principles of oral and maxillofacial surgery. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 2004. p. 1224. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rauso R, Gherardini G, Tartaro G, Curinga G, Nesi N, Santagata M. A modified alar cinch suture technique. Eur J Plast Surg. 2009;32:341–344. doi: 10.1007/s00238-009-0348-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurice Y, Mommaerts MY, Lippens F, Abeloos JV, Neyt LF. Nasal profile changes after maxillary and advancement surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:470–475. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(00)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen HM. Lip–nasal aesthetics following Le Fort I osteotomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81(2):171–179. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198802000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guymoon M, Crosby DR, Wolford L. The alar base cinch suture to control nasal width in maxillary osteotomies. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1988;3(2):89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howley C, Ali N, Lee R, Cox S. Use of the alar base cinch suture in Le Fort I osteotomy: Is it effective? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;49(2):127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schendel SA, Williamson LW. Muscle re-orientation following superior repositioning of the maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:235–240. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westermark AH, Bystedt H, von Konow L, Sällström KO. Nasolabial morphology after Le Fort I osteotomies, effect of alar base suture. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;20(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80690-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shoji T, Muto T, Takahashi M, Akizuki K, Tsuchida Y. The stability of an alar cinch suture after Le Fort I and mandibular osteotomies in Japanese patients with Class III malocclusions. Br J Oral Maxilofac Surg. 2012;50(4):361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart A, Edler RJ. Efficacy and stability of the alar base cinch suture. Br J Oral Maxilofac Surg. 2011;49(8):623–626. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]