Abstract

Purpose

The treatment of lip carcinomas needs tumor surgical resection with safety margins respect. The aim of this study was to report the oncologic and aesthetic/functional outcomes of a retrospective monocentric case series of 39 patients treated for cutaneous lip cancer.

Methods

This retrospective study assessed 56 patients who were treated for a lip carcinoma between 2008 and 2012 and included 39 patients with cutaneous lip basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical, surgical and pathological data were reviewed, and patients were interviewed for follow-up data. A comparison was made between the marked surgical margins and the margins observed under microscopy after histologic process.

Results

The most frequent tumor type was basal cell carcinoma in 69.2 %. The measured surgical margins were superior to the histological margins in 24 cases (61.5 %) and were inferior in 13 cases (33.3 %). Overall survival and recurrence-free survival rates at 1 year were 97.5 and 95 % respectively.

Conclusion

Differences between the surgical margins and the final histologic margins were the main finding of this retrospective study. These differences were attributed to surgical practices and modification during the histological process. Nevertheless, we did not observe a higher rate of recurrence or death in our study than in literature.

Keywords: Tumor recurrence, Basal cell carcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma, Lip carcinoma

Introduction

Cutaneous carcinomas of the lip are common cancers of the head and neck region [1]. They mainly include basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which are invasive malignant epidermal tumors predominantly affecting the occidental population.

BCC is the most common cancer in Europe with a mean age of onset of 60 years, whose incidence is increasing worldwide, especially when it is located in the lip area [2]. It usually affects exposed cutaneous areas, including the head and neck region in 80 % of cases [3]. SCC of the lip is found on the lower lip in 95 % of cases, whereas BCC is often located on the upper lip [4]. The risk of lip cancer increases with UV exposure, smoking and some specific genetic diseases or viral infection [5].

Many treatments have been described for the management of lip carcinoma, but the medical decision is exclusively based on the prognosis of the tumor that will orientate the treatment choice. The most important factor influencing the treatment scheme is the lesion size. The efficacy of the treatment is based on the absence of local recurrence for BCC and on the absence of local or lymph node recurrence for SCC. Respecting the tumor safety margin of 3 mm for BCC and 10 mm for SCC is essential [6].

The postoperative quality of life of patients who have undergone large lip excision surgery has to be assessed using specific scales. Therefore, an adequate assessment of the treatment result should include the overall health condition, surgical outcome, including wound-healing disorders, oncologic outcomes, recurrences, and functional and aesthetic results.

The aim of this study was to report these outcomes in a retrospective case series of 39 patients treated for cutaneous cancer of the lip.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Data were collected from patient electronic medical records following our ethics committee recommendations.

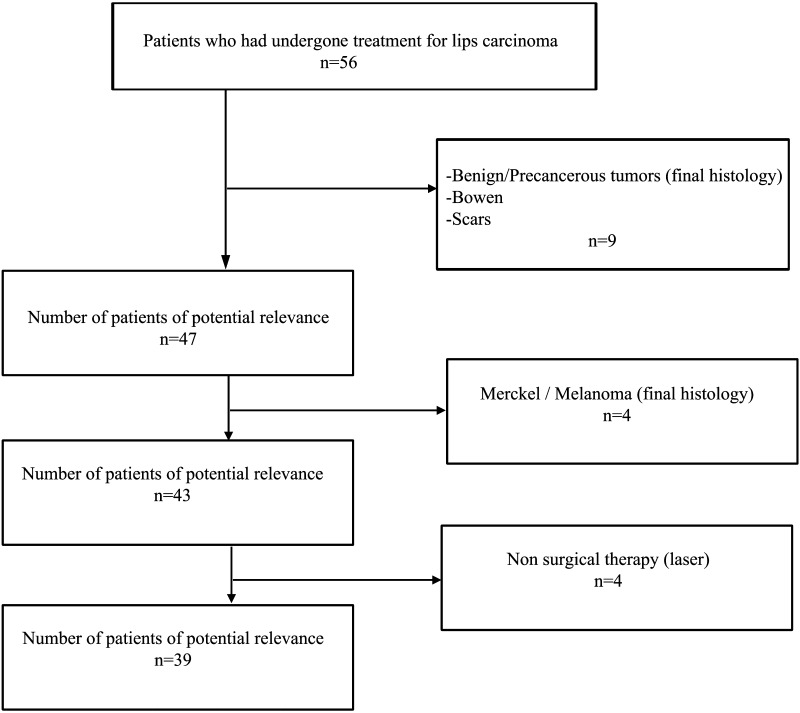

Between 2008 and 2012, a total of 56 patients with tumors of the upper or lower lip were treated by two senior surgeons in our Department. Only patients with a histological confirmation of BCC or SCC of the lip were included.

Inclusion criteria were:

having a cutaneous BCC or cutaneous SCC of at least one lip

having been treated with surgical therapy

having undergone a histological analysis.

Exclusion criteria were defined as follows:

presenting with a mucosal involvement, benign tumors, a pre-cancerous lesion, Merkel cell carcinoma or melanoma;

having been treated with non-surgical therapies.

Based on these criteria, 39 patients were included (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow-chart

Methods

Due to the retrospective design of the study, an exemption for informed consent agreement was granted by the University of Paris Est Creteil institutional review board.

The medical records were retrospectively analyzed, and patient characteristics and medical and surgical features (age, gender, histological diagnosis, lesion location, width and size, excision margins, reconstructive technique, recurrences, and functional and cosmetic outcomes) were collected retrospectively using a standardized approach.

The oncologic, functional and aesthetic outcomes were collected by phone call for each patient at least 1 year after surgery using a standardized questionnaire and Likert scales.

The oncologic outcomes were defined as a local or nodal recurrence after primary surgical treatment (yes vs. no, time since surgery).

The aesthetic assessment was only based on the patient opinion: “very poor”, “poor”, “good” and “very good”. Patients were also questioned about their functional outcome (sensitivity, closing of the lips, phonation). The patients who could not be reached were classified as “lost to follow-up” for the quality of life assessment.

Surgery was performed using a standardized approach under local anesthesia with intravenous sedation or general anesthesia at Henri Mondor Hospital following the French Society of Dermatology recommendations [7, 8]. No patient was operated using Mohs surgery. The margins were determined by multidisciplinary committees in oncology based on the histological and surgical parameters and the overall health condition of the patient and were marked with ink around the assessed tumor contours before excision (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Example of margin drawing for BCC of the upper lip before surgical resection

The effective microscopic margins were determined during the histological assessment.

The margin difference (ΔM) in millimeters and in percentage was measured between the desired margins and the obtained margins. When the ΔM was negative or equal to zero, the margins were considered sufficient, and when the ΔM was positive, the margins were considered insufficient. In the presence of insufficient margins and a histological report of remaining tumor, a revision surgery was performed. The three surgical techniques used were excision with direct closure, excision with a local flap and excision with a skin graft.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using a statistical software package (Xlstat, Addinsoft 2012). A regression analysis was used to compare the recurrence-free survival and the ΔM.

Results

Thirty-nine patients were treated for cutaneous SCC or BCC of the lip in the Department of Plastic, Aesthetic and Reconstructive Surgery between 2008 and 2012. Table 1 presents patient clinical characteristics and details of the tumor location on the lips.

Table 1.

Summary of patient

| Patient data (n = 39) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 21 | 53.8 |

| Female | 18 | 46.2 |

| Age, mean (range) | 72.4 | 26–94 |

| Histologic diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| BCC | 27 | 69.2 |

| SCC | 12 | 30.8 |

| Location, n (%) | ||

| Upper lip | 27 | 69.2 |

| Lower lip | 9 | 23.1 |

| Upper and lower lips | 1 | 2.6 |

| Lower lip and commisure | 2 | 5.1 |

| Distribution lip-histology (n) | Upper lip | Lower lip |

|---|---|---|

| BCC | 24 | 3 |

| SCC | 3 | 9 |

| Lesion size (mm) | ||

| Median (range) | 11 | 1–50 |

| Average | 13.6 | |

| Mean of margins (mm) | ||

| Surgical margin | 5.8 | |

| Histological margin | 3.5 | |

| Difference of margin, ΔM (%) | 36.9 |

There were 27 BCC and 12 SCC. BCC and SCC were respectively predominantly found in the upper lip (88.9 % of BCC) and lower lip (66.7 % of SCC). In one patient, both lips were affected by SCC. The distribution of histologies is detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Histologic results

| Histologic data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Perineural invasion | ||

| SCC (12) | ||

| Invasive | 11 | 2 |

| In situ | 1 | – |

| BCC (27) | ||

| Invasive | 17 | – |

| Nodular | 5 | – |

| Superficial | 5 | – |

The histological mean diameter of the tumor was of 13.6 mm, varying from 1 mm (complete excision during biopsy) to 50 mm, and its median diameter was of 11 mm. The mean surgical margin was of 5.8 mm, and the mean histological margin was of 3.5 mm. The measured surgical margins were greater than the histological margins in 24 cases (61.5 %). The histological margins were greater than the margins expected preoperatively in 13 cases (33.3 %). The margin size was missing in two patients. Twenty patients (51.3 %) had a ΔM less than or equal to 1 mm (ΔM ≤ 1 mm), and 10 patients (25.6 %) had a ΔM ≥ 5 mm. Complete tumor excision with safe margins was achieved in 35 patients (90 %). Four patients (10 %) underwent revision surgery: 2 patients for incomplete excision and 2 for insufficient margins; two of these patients had BCC, and two had SCC. After the second surgery, no additional surgery was needed.

Spindle-shaped excision was performed in 37 cases and vermillionectomy in 2 cases. Tumor excision was followed by reconstruction of the defect. Direct closure was applied in 14 cases, local flaps in 24 cases and a full-thickness skin graft in 1 case. Among them, there were 29 primary excisions and 10 secondary excisions.

Among all patients, only two (5 %) experienced a local recurrence over the 38-month follow-up period.

Cervical node metastasis was found in 2 patients with SCC, and bilateral lymphadenectomy was performed in both cases. Both patients received an adjuvant treatment with radiotherapy. No patient received chemotherapy.

Among the 39 patients, 2 died (malnutrition and prostate cancer) and 4 were lost to follow-up during the study period. No functional disorder was observed in 22 patients, and a slight discomfort after the surgery was reported by only 6 patients. Two experienced major labial disorders (difficulty in closing the lips during eating). Only one patient requested further surgery.

Discussion

Differences between surgical margins and final histological margins was the main finding of this retrospective study. These differences were attributed to surgical practices and changes during the histological process. Nevertheless, we did not observe a higher rate of recurrence or mortality in our study during the follow-up.

Surgical resection is the accepted standard of care for both SCC and BCC of the lip. Radiotherapy is also indicated [9, 10]. This method allows a high cure rate by controlling the histological margins. In our study, all patients were operated by two experienced surgeons to reduce the risk of bias related to the operator.

If complete excision is the goal, then the histological margins of the normal tissue will need to be demonstrated around the tumor, with the histopathologist able to report the measured clearance margins both peripherally and in depth [11]. For patients treated with surgical excision, very high success rates, in term of tumor removal, should be expected. The British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) estimates that if tumors such as BCC were removed with a 3-mm clinical margin, it can then be expected that, microscopically, the tumors would be adequately excised in 85 % of cases [12]. In this retrospective study, no intraoperative frozen section biopsy was taken.

Van der Eerden et al. [13] have shown a local recurrence rate of 1.8 % for surgically excised SCCs of the head and neck region with a mean follow-up of 16 months.

Papadopoulos et al. [14] have demonstrated in a large series of lip cancer patients that surgical excision followed by direct repair was associated with a higher 5-year recurrence rate than excisions followed by reconstruction using several types of flaps. In their series of 899 patients, the 5-year disease-free survival rate was 88.72 %, and the 5-year recurrence rate was 11.28 %. In our study, 24 patients (61.5 %) underwent direct lip reconstruction with a local flap. Among them, no patient experienced recurrence in the first year or at the end of the follow-up period. There were two recurrences (14.3 %), one BCC and one SCC, when direct closure was performed but this number did not correlate with the closure method due to the low number of patients included in this study. Surgical resections for tumors involving more than 1/3 of the lip cannot benefit from direct closure when healthy margins of 1 cm are expected.

Casal et al. [15] have observed a local recurrence in 12.8 % of lip carcinoma patients, with a mean time to recurrence of 35.1 ± 34.2 months. The 5-year lip cancer mortality rate in their series was 8.3 %. In our study, the mean follow-up duration was 38 months, and among the seven patients with a 5-year follow-up we found 1 recurrence (14 %) and 2 deaths in patients with SCC.

It has previously been shown that there is a slight male preponderance in the gender distribution, and we found an increased incidence of lip cancer with age, in accordance with previous studies [16, 17]. According to the literature, this finding could be associated with the frequent use of lipstick, a protector against ultraviolet (UV) exposure by women, making them less susceptible [18]. The influence of the gender as well as age may be explained by the exposure to environmental carcinogens such as tobacco or UV over time [19].

The most frequent carcinoma occurring on the lips is SCC, followed by BCC [14], but in our study, there were more BCC than SCC. This difference could be explained by the more frequent location in the upper lip in our study.

As most other authors, we found BCC almost exclusively in the upper lip [20, 21]. SCC was frequently located in the lower lip, which is also in line with previous studies [1, 3, 4].

We excluded from the study malignant tumors such as melanoma and Merkel cell carcinoma because of the differences in prognosis and local and distant metastases.

Although cutaneous SCC and BCC of the lips are two different pathological entities with different risk factors and course, we deliberately chose to study these patients in the same group because in the absence of lymph node involvement, the process of initial surgical treatment is very similar [9, 10].

The primary goal of the surgical treatment of lip tumors is three-dimensional tumor resection with histologically clear margins. This goal should be balanced, however, with an acceptable functional and aesthetic outcome.

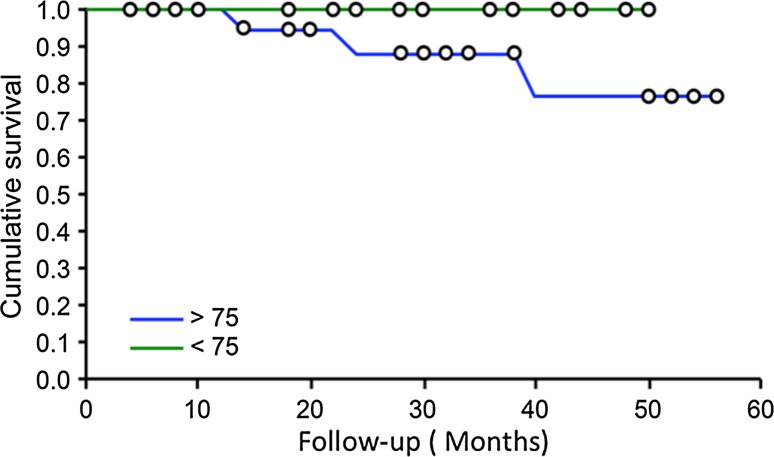

An analysis of our data suggests that differences between surgical margins and histological margins were important. The mean ΔM was 36.9 %. Only 5.1 % of patients underwent a revision surgery because of poor margins. This value could be explained by the presence of tissue changes that occurred during the sample and histological preparation. In the literature, others have already highlighted differences between clinical and histological margins [22]. Despite this difference, we did not find differences in recurrence rates due to insufficient margins during the follow-up period for both SCC and BCC. Two recurrence-free survival curves for both SCC and BCC were plotted to determine the risk of death in subjects over 75 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparative recurrence-free survival in patients aged under or over 75 (Kaplan–Meier curves)

The 2 patients who died during the follow-up period were treated for BCC. They presented with multiple pathologies without direct correlation with their lip carcinoma.

Only one patient (2.6 %) reported a significant discomfort and requested a surgical correction. Local flaps were used in the first intervention (61.5 % of cases), but we observed no difference in patient satisfaction between the different reconstruction techniques used. We did not need to use free flaps for lip reconstruction. Ten percent of patients experienced a slight discomfort but they did not need a second surgery. Patients over 80 and those who presented important comorbidities did not undergo a second resection of the margins when the lesion was completely removed, although the margins were insufficient. All decisions were made with the help of multidisciplinary committees and a geriatrician.

Conclusion

This retrospective study included patients treated for cutaneous BCC or SCC of the lips. An analysis of the outcomes and survival curves shows that our results are within the normal range in the literature. Important differences were noted between the margins determined by multidisciplinary committees in oncology, surgical margins determined during surgery and histological margins. In our series, surgical margins after lip carcinoma resection did not affect the 1-year recurrence-free survival for both BCC and SCC. However, a prospective study is needed to confirm our findings in a larger number of patients. In most of our patients, no functional or aesthetic disorder was reported after the surgery.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Oana Hermeziu from the plastic and reconstructive surgery department for her careful review of the manuscript and the data collection. We are very grateful to Dr. Ouidad Zehou of the Dermatology Department for having provided valuable advice on our manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. Oral pathology: clinical pathologic correlations. 5. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008. pp. 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Telfer NR, Colver GB, Morton CA. Guidelines for the management of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(1):35–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin AI, Chen EH, Ratner D. Basal-Cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(21):2262–2269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra044151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faulhaber J, Géraud C, Goerdt S, Koenen W. Functional and aesthetic reconstruction of full-thickness defects of the lower lip after tumor resection: analysis of 59 cases and discussion of a surgical approach. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(6):859–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehanna H, Beech T, Nicholson T, El-Hariry I. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of trends by time and region. Head Neck. 2013;35(5):747–755. doi: 10.1002/hed.22015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ANAES Good clinical practices. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of basal cell carcinoma in adults. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofacc. 2005;106(2):83–88. doi: 10.1016/S0035-1768(05)85815-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulomb A. Recommendations for basal cell carcinoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131(6):661–756. doi: 10.1016/S0151-9638(04)93749-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin L, Bonerandi JJ. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136(5):163–164. doi: 10.1016/S0151-9638(09)75170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell JP. Surgical management of lip carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56(8):955–961. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(98)90658-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lansbury L, Leonardi-Bee J, Perkins W, Goodacre T, Tweed JA, Bath-Hextall FJ. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;4:CD007869. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007869.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffiths RW, Suvarna SK, Stone J. Basal cell carcinoma histological clearance margins: an analysis of 1539 conventionally excised tumours. Wider still and deeper? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel SS, Cliff SH, Ward Booth P. Ward Booth P. Incomplete removal of basal cell carcinoma: what is the value of further surgery? Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;17(2):115–118. doi: 10.1007/s10006-012-0348-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Eerden PA, Prins MEF, Lohuis PJFM, Balm FAJM, Vuyk HD. Eighteen years of experience in Mohs micrographic surgery and conventional excision for nonmelanoma skin cancer treated by a single facial plastic surgeon and pathologist. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(12):2378–2384. doi: 10.1002/lary.21139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papadopoulos O, Konofaos P, Tsantoulas Z, Chrisostomidis C, Frangoulis M, Karakitsos P. Lip defects due to tumor excision: apropos of 899 cases. Oral Oncol. 2007;43(2):204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casal D, Carmo L, Melancia T, Zagalo C, Cid O, Rosa-Santos J. Lip cancer: a 5-year review in a tertiary referral centre. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(12):2040–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morton RP, Missotten FE, Pharoah PO. Classifying cancer of the lip: an epidemiological perspective. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1983;19(7):875–879. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(83)90050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czerninski R, Zini A, Sgan-Cohen HD. Lip cancer: incidence, trends, histology and survival: 1970–2006. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(5):1103–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Souza RL, Fonseca-Fonseca T. Lip squamous cell carcinoma in a Brazilian population: epidemiological study and clinicopathological associations. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16(6):757–762. doi: 10.4317/medoral.16954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson DL. Cause and prevention of lip cancer. J Can Dent Assoc. 1971;37(4):138–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zitsch RP, 3rd, Park CW, Renner GJ, Rea JL. Outcome analysis for lip carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113(5):589–596. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silapunt S, Peterson SR, Goldberg LH, Friedman PM, Alam M. Basal cell carcinoma on the vermilion lip: a study of 18 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(3):384–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dauendorffer JN, Bastuji-Garin S, Guéro S, Brousse N, Fraitag S. Shrinkage of skin excision specimens: formalin fixation is not the culprit. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(4):810–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]