Abstract

Despite advancements in medical therapy of Crohn’s disease (CD), majority of patients with CD will eventually require surgical intervention, with at least a third of patients requiring multiple surgeries. It is important to understand the role and timing of surgery, with the goals of therapy to reduce the need for surgery without increasing the odds of emergency surgery and its associated morbidity, as well as to limit surgical recurrence and avoid intestinal failure. The profile of CD patients requiring surgical intervention has changed over the decades with improvements in medical therapy with immunomodulators and biological agents. The most common indication for surgery is obstruction from stricturing disease, followed by abscesses and fistulae. The risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in CD is high but the likelihood of needing surgery for bleeding is low. Most major gastrointestinal bleeding episodes resolve spontaneously, albeit the risk of re-bleeding is high. The risk of colorectal cancer associated with CD is low. While current surgical guidelines recommend a total proctocolectomy for colorectal cancer associated with CD, subtotal colectomy or segmental colectomy with endoscopic surveillance may be a reasonable option. Approximately 20%-40% of CD patients will need perianal surgery during their lifetime. This review assesses the practice parameters and guidelines in the surgical management of CD, with a focus on the indications for surgery in CD (and when not to operate), and a critical evaluation of the timing and surgical options available to improve outcomes and reduce recurrence rates.

Keywords: Surgery, Crohn’s disease, Major abdominal surgery, Perianal, Inflammatory bowel disease, Colon cancer

Core tip: Despite significant advances in the medical management of Crohn’s disease (CD), most patients will still need surgery during their lifetime, with a third requiring multiple surgeries. It is important to optimise the surgical management of CD in order to reduce rates of emergency surgery, surgical recurrence and intestinal failure. Surgical options depend on the phenotype of CD. The most common indications for surgery include stricturing disease, fistulae and abscesses whereas surgery for bleeding and cancer associated with CD is less common. It is vital to understand the role and timing of surgery, and the best surgical options in the management of CD.

INTRODUCTION

Seventy to ninety percent of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) will eventually need surgery[1]. The likelihood of surgery in CD after initial diagnosis has been reported in a recent systematic review to be 16.3% at one year, 33.3% at three years and 46.6% at 5 years[2]. The surgical mortality rate is 0%-8.4%[3-5], with most deaths resulting from intra-abdominal sepsis. Absolute indications for surgery in CD include cancer, perforation, toxic megacolon and major life-threatening gastrointestinal tract (GIT) bleeding. Relative indications include strictures, phlegmon, fistulae, intra-abdominal abscesses, GIT bleeding, dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM), high grade dysplasia detected on surveillance, growth retardation in children and failure of medical therapy. The decision of when to operate is difficult in CD. Delaying surgery for prolonged medical management may increase complication rates as well as increasing the technical difficulties encountered during surgery and the rates of emergency surgery, which is associated with increased stoma rates and at least a three-fold increase in mortality compared to elective surgery.

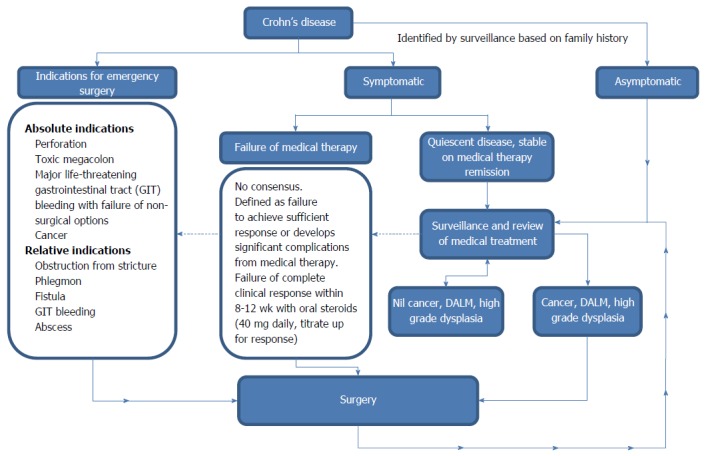

CD is associated with high surgical recurrence, such that most patients with CD will have multiple operations during their lifetime and 5%-18% of patients eventually require parenteral nutrition for intestinal failure[6,7]. The risk of intestinal failure rises significantly with multiple surgeries, particularly when intestinal length is shorter than 150 cm[7] and is imminent when intestinal length is less than 100 cm[8]. This review assesses the available evidence in the current literature on the surgical management of CD, focusing on the indications for surgery (Figure 1) and the surgical options for small bowel, large bowel and perianal CD.

Figure 1.

Indications for surgery in Crohn’s disease. DALM: Dysplasia-associated lesion or mass.

LITERATURE SEARCH

The Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines was used in this review. Two databases (MEDLINE and Embase from 2010-2016). Search terms included “Crohn’s disease”, “perianal”, “large bowel” or “large intestines” or “colon”, “small bowel” or “small intestines” and “surgery” or “surgical indications”. Five hundred and ten studies were identified through MEDLINE and Embase, 189 additional studies were found from hand-searching references.

Abstracts were reviewed by two investigators independently, and only studies excluded by both investigators were excluded. When only one investigator excluded the study, these studies were included for full text review. Studies excluded based on abstract included non-human studies, non-English language, studies on immunomodulators and biological agents only, no reference to surgery for CD, reference to ulcerative colitis only, upper gastrointestinal CD only or inflammatory bowel disease in general but not specifically CD. Studies reporting mainly on immunomodulators but with references to surgery and studies on inflammatory bowel disease with reference to CD were included for full text review. Only studies which reported on indications and surgical options for small bowel, large bowel or perianal CD were eligible for qualitative synthesis. One hundred and twenty-eight full text studies were reviewed after duplicates were removed. One hundred and fifteen studies were included in this review.

INDICATIONS FOR MAJOR GASTROINTESTINAL SURGERY IN CD

Stricture and obstruction

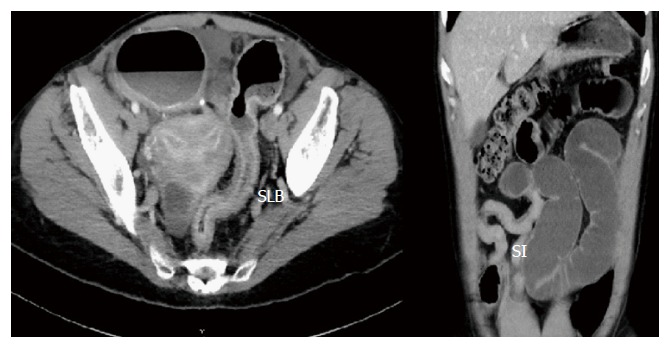

Bowel obstruction from stricture (Figure 2) is the most common reason for surgery in CD[9]. Stricturing phenotype of CD is most common in ileal disease and in patients diagnosed with CD at a younger age. Patients may also develop anastomotic fibrotic strictures post-surgery for CD. Stricturing disease phenotype has often been associated with penetrating disease phenotype.

Figure 2.

Stricturing disease. SLB: Strictured large bowel; SI: Strictured ileum.

Intraabdominal phlegmon, abscesses and fistulae

Abscesses, phlegmons and fistulae in CD are associated with a penetrating phenotype. Younger patients with CD are more likely to have penetrating disease[10]. Intra-abdominal abscesses are common in CD, and may be associated with fistulae and/or intra-abdominal sepsis. Approximately one third of patients with CD develop intra-abdominal fistulae during their lifetime. Enteroenteric fistulae are the most common, followed by enterocutaneous and enterosigmoid fistulae[11]. Pregnancy is associated with higher rates of intestinal-genitourinary fistulas[12]. Occasionally, patients may present with phlegmon without abscess or fistula.

Perforation

Free perforation is the initial symptom of CD in 1%-3%[13] up to 30%[14]. Free perforation is the indication for surgery in 1%-16% of surgical intervention in CD[15]. The mean time from initial diagnosis to perforation is approximately 3 years, shorter in duration than development of fistulas, strictures and intra-abdominal abscesses[14]. Perforation may be from regional severe colitis or ileitis, or from toxic megacolon associated with fulminant colitis. A high index of suspicion is required as corticosteroids may mask the symptoms of perforation, leading to delayed management and increased mortality risk.

Failure of medical therapy

Failure of medical therapy is defined as failure to achieve sufficient response, development of significant complications from medical therapy, non-compliance with medical therapy, incompatibility with lifestyle or livelihood and steroid dependence with intolerability to other medications. There is no consensus as to what is sufficient response. A common definition is failure of complete clinical response with 8-12 wk of oral steroids and other agents. Approximately 20%-30% of CD patients do not respond to steroids, and up to 45% of CD patients will relapse on weaning of steroids[16]. Patients who have good response to medical therapy, and are able to tolerate immunosuppressants are usually recommended to remain on therapy for at least 3 to 4 years to reduce the likelihood of early relapse[17].

Oral prednisolone is usually started at 40 mg daily, and titrated up for clinical response for up to 12 wk[18] with commencement of immunomodulators or biological agents. As immunomodulators take up to 16 wk for response, some definitions of failed therapy suggest ongoing symptoms and signs despite medical therapy for up to 16 wk.

Major gastrointestinal bleeding

Severe gastrointestinal haemorrhage is rare[19]. Approximately 5% of CD patients will experience a major GIT bleed during their lifetime. It most commonly arises from ulcerated colonic areas, with colonic involvement more likely than small bowel involvement[20].

Toxic megacolon

In CD, the rate of toxic megacolon is approximately 2%[21]. Toxic megacolon is defined by total or segmental colonic distension and systemic toxicity[22]. Toxic megacolon may be associated with fulminant colitis and with co-infections such as clostridium difficile. Toxic megacolon may be associated with commencement of narcotics and anti-diarrhoeals used to manage bloody diarrhoea associated with severe colitis. For this reason, in general, anti-diarrhoeals should be avoided in management of colitis associated with CD.

Neoplasia and dysplasia

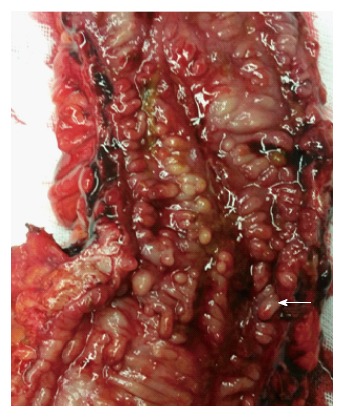

Cancer of the small bowel and colon is an absolute indication for surgery. The risk of cancer ranges from 1%-5% in CD[9,23,24], representing a 2-3 times increased risk of developing colorectal cancer and > 18 times increased risk of developing small bowel cancer when compared to the general population[25,26]. Patients may present with bowel obstruction (Figure 3), bleeding or non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms, or cancer may be detected during surveillance colonoscopy. Colorectal cancer in CD usually develops at an earlier age when compared to the baseline population[27]. For patients with CD colitis, the risk of developing cancer is 3%-4%[28]. Severe ileitis is associated with increased risk of small bowel cancer (approximately 2%). Dysplasia, earlier age of diagnosis of CD, extensive colitis or ileitis, length of disease > 10 years, presence of pseudopolyps (Figure 4), presence of anal fistula or other penetrating disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis is associated with increased risk of cancer in CD[28,29].

Figure 3.

Large bowel stricture in Crohn’s disease. Final pathology adenocarcinoma (arrow).

Figure 4.

Pseudopolyps (arrow marks a pseudopolyp) in Crohn’s disease.

Growth retardation

One in 4 patients with CD are diagnosed before the age of 18 years old. CD has a bimodal distribution, with patients diagnosed during childhood and adolescence with a more severe phenotype. Growth retardation is associated with poor nutritional status associated with CD due to malabsorption and administration of corticosteroids[30].

SURGICAL OPTIONS IN SMALL BOWEL AND LARGE BOWEL CD

Stricture and obstruction

Stricturing CD, when associated with internal fistula, small bowel obstruction, bowel dilation > 3 cm or inflammatory phlegmon or abscess, are considered high risk strictures that usually require surgery[31]. Patients with fibrotic anastomotic strictures rather than de novo strictures are also more likely to require surgery[32].

Surgical options include resection of stricture with primary anastomosis or stricturoplasty. Stricturoplasty leads to higher surgical recurrence than resection[33].

Ileocolic

The most common surgery for stricturing disease in CD is ileocolic resection for ileocaecal or distal ileal disease[9]. Approximately 87% of patients with ileocaecal disease eventually require resection[34]. A significant proportion ileocolic resections for CD are performed in the emergency setting[35]. While there is no benefit from initiation of anti-TNF therapy prior to surgery for patients with severe ileocaecal CD[36], there is evidence that percutaneous drainage of abscess prior to surgery reduces the risk of anastomotic leak and rates of faecal diversion and this should be considered in stable patients without generalised peritonitis or clinical deterioration. If a CD patient is dependent on steroids and has a pre-operative abscess and requires immediate surgery, the risk of anastomotic complications is 40% and a stoma should be strongly considered[35].

Eighty percent of ileocolic resections are without clinical recurrence at 2 years[37] and the long term relapse rate is 36%[34]. Ileocolic resections are often complicated by chronic diarrhoea due to loss of ileocaecal valve[38]. Novel methods of forming pseudo-valves, such as the nipple valve anastomosis technique have been reported[39], but there is no evidence to recommend routine formation of pseudovalves post ileocolic resection.

Approximately 30% of patients post ileocolic resection develop an anastomotic stricture. Dealing with an anastomotic stricture associated with recurrent CD is difficult and usually require resection if endoscopic balloon dilatation (EBD) fails. Stricturoplasties are associated with short term resolution of symptoms but a higher rate of recurrence than for resection[40], particularly in children and adolescents with CD.

Ileal

Stricturoplasties are considered a safe alternative to resection and are an important strategy to preserve bowel length.

The Heineke-Mikulicz and Finney techniques are the most common types of stricturoplasty procedures[41]. Other techniques of stricturoplasties such as the Michelassi technique and modified approaches have also been reviewed in meta-analyses, and are considered safe[42].

Colonic

For large bowel strictures not complicated by fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon or cancer, segmental resection and anastomosis with or without diversion for localised disease offers better quality of life, although it is associated with a higher risk of recurrence. Prabhakar et al[43] reported on 49 patients who had segmental colon resection without a permanent stoma for primary colonic CD followed up for over 10 years. Forty-five percent required no further treatment, 22% required medical therapy (only 8% required medical therapy for > 1 year) and only 33% required re-operation (10% multiple re-operations). A significant proportion remained stoma free, and of those who subsequently required a stoma, the average stoma-free interval was approximately 2 years.

A meta-analysis by Tekkis et al[44] reported that segmental colectomy with primary anastomosis was just as good as colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis for single segment colonic CD with no increase in recurrence. Recurrence rates only increased when segmental colectomies were performed for CD patients who had two or more colonic segments involved[44]. For this reason, segmental resections for localised colonic CD strictures or colitis is a reasonable option. Total colectomy is reserved for patients with multiple strictures, severe pancolitis, fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon or cancer.

Stricturoplasties may be performed for CD large bowel strictures with good functional outcomes[45]. It is not commonly performed as it is associated with increased recurrence rates when compared to resection[45]. There is however, no evidence that large bowel stricturoplasty increases the leak rate when compared to resection[45].

Non-surgical management of strictures

Not all stricturing disease requires surgery. The benefit of EBD is that 1 in 2 have sustained response and may avoid surgery[46], albeit requiring repeated EBD. Repeated interval stricture dilation has been successful in delaying the need for surgery without significant morbidity[47,48].

Despite short term success rates for EBD being favourable[49,50], there is an increased rate of re-intervention and complications with EBD. The long-term outcome after surgery is better than for EBD[51] and salvage surgery after failure of EBD is associated with higher risk of stoma, surgical site infections, reoperations and readmissions when compared with surgery first approach[52].

Stenting for CD strictures has been described in case reports with reasonable short term outcomes[53-55]. However, this is not commonly performed, and there is insufficient evidence to recommend this practice.

Intraabdominal phlegmon, abscesses and fistulae

Phlegmons: Abdominal phlegmons may be treated non-surgically with antibiotics and anti-TNF therapy without the need for surgery if the patient is stable with no evidence of generalised peritonitis or clinical deterioration. Successful management of phlegmon long term has been reported in the literature[56].

Intra-abdominal abscesses: The majority of intra-abdominal abscesses require definitive surgical management and intestinal resection[57]. Immediate surgical intervention should only be reserved for unstable patients with generalised peritonitis or clinical deterioration.

Drainage of abscess prior to surgery and delaying surgery reduces the risk of anastomotic complications. Emergency surgery for intra-abdominal abscess when patient is septic and on steroids is associated with high anastomotic leak rates[35].

There is, however, a high failure rate with percutaneous drainage alone. In paediatric patients with intraabdominal abscesses, over 60% of patients initially managed medically or treated with percutaneous drainage will require surgery within 1 year[57]. In adult CD, medical management and percutaneous drainage alone without removing the diseased intestine is associated with an unacceptably high failure rate[58], particularly for patients with larger abscesses or abscesses with a detectable fistula on imaging[59].

It is reasonable to consider non-surgical treatment of abdominal abscesses if there is no abscess or fistula on repeat imaging and there is no ongoing steroid requirement[60]. Initial management with non-surgical management may reduce the need for surgery in a small number of cases[61], although majority require surgery.

For larger or complex abscesses or when associated with fistula, planned bowel resection after initial management with percutaneous drainage of abscess, high dose steroids (up to 300 mg IV hydrocortisone per day) and IV antibiotics for at least 5 d increases the likelihood of primary anastomosis without the need for ileostomy, and avoids the morbidity of high failure rates with conservative management alone[58].

There is no evidence for surgical drainage of abscess without intestinal resection. This has no advantage over percutaneous drainage[62].

Intra-abdominal fistulae: Anti-TNF therapy heals about one third of fistulae. The rest require surgery. Traditionally, majority of intra-abdominal fistulae undergo intestinal resection and primary anastomosis[11]. The main caveats in CD fistula are large bowel fistulae are more likely to require surgery than small bowel fistulae[63] and colo-cutaneous and entero-cutaneous fistulae usually require surgical intervention[64], although in the era of anti-TNF therapy, medical management facilitates fistulae closure in up to one-third of patients[65]. (1) Small bowel fistulae: Long term remission may be achieved with medical therapy, such as ileovesical fistulae when there are no other CD complications. However, when small bowel CD fistulae are complicated by intraabdominal abscesses, small bowel obstruction or enterocutaneous fistulae, most cases usually still require surgery[63]. Surgery for enteric fistulae is associated with low rates of complications and recurrence[66]. Small bowel resection with primary anastomosis without diversion is usually associated with reasonable outcome. And (2) Large bowel fistulae: Surgery is nearly always indicated. A common large bowel fistula is the ileo-sigmoid fistula (Figure 5), which is a well-known manifestation of CD. These patients require ileocolic resection and either primary repair or segmental resection of the sigmoid, or a subtotal colectomy. In a study of ileocolic resection and primary repair of sigmoid vs ileocolic resection and segmental resection of sigmoid vs subtotal colectomy, ileocolic resection with primary repair or segmental sigmoid resection was shown to have comparable morbidity[67]. However, there have been reports of increased rates of postoperative sepsis with sigmoidectomy when compared with primary repair of sigmoid[68]. Subtotal colectomy is not required unless there is moderate-severe pancolitis.

Figure 5.

Ileosigmoid fistula with arrow marking contrast. Contrast flowing from ileum to sigmoid. I: Ileum; S: Sigmoid.

Perforation

Perforation is an absolute indication for surgery. Surgical management depends on the site of perforation. Simple suture closure of the perforation is associated with a high mortality rate, and intestinal resection of the perforated viscus is warranted. If there is faecal contamination, abscess or the patient is on high dose steroids, then primary anastomosis is associated with significant risk of anastomotic complications. Patients on corticosteroid dose equivalent to 20 mg of prednisolone or greater have anastomotic complication rates of up to 20%[69]. If perforation is associated with severe ileitis, a temporary abcarian stoma may be safer than primary anastomosis. If perforation is associated with severe CD colitis, a segmental resection, subtotal or total colectomy and end ileostomy may be performed with an exteriorised mucus fistula or stump placed intraperitoneally or subcutaneously. In considering whether to provide the patient with a stoma in the setting of perforated CD, high degree of contamination, low albumin[70] and presence of intra-abdominal abscess[35] should be considerations towards faecal diversion.

Failure of medical therapy

CD patients who continue to have symptoms of abdominal pain, severe diarrhoea, bleeding, obstructive symptoms, weight loss, malabsorption, dehydration or signs of systemic toxicity despite 12-16 wk of medical therapy including steroids and first and second line immunomodulators and biological agents require surgery. Surgical options depend on the phenotype of CD.

In patients with severe CD requiring emergency admission to the hospital, failure to improve with steroids over a 72 h period may require escalation to surgery.

Not all patients should wait 12-16 wk before escalating to surgery, particularly patients with severe stricturing ileocolic disease which usually fails conservative management[36], or patients with risk factors for further medical therapy. These patients should have surgery earlier than 12-16 wk if not responding early to medical therapy.

Major gastrointestinal bleeding

The majority of bleeding resolves spontaneously or with medical management - conservative measures are successful in 80% of cases. This includes blood transfusions, supportive measures, corticosteroids, cyclosporins and biological agents. However, 40% of patients with massive bleeding experience severe re-bleeding episodes. Medications such as infliximab are useful in combating the long term risk of bleeding recurrences[71]. To control acute massive bleeding, interventions such as angio-embolisation and endoscopic treatment should be attempted, but often fail. This is because of difficulties in identifying a precise bleeding point both angiographically and endoscopically as bleeding usually occurs in multiple inflamed areas[20]. From a therapeutic point of view, endoscopic or radiological haemostasis has a low rate of success[19].

Surgery is reserved to salvage patients with intractable bleeding who clinically deteriorate or become haemodynamically unstable[72]. A total colectomy is indicated in life-threatening cases refractory to non-surgical management. Surgery usually is effective with a low risk of rebleeding[20], however is associated with high morbidity.

Toxic megacolon

A diameter of the transverse colon of > 5.5 cm with systemic toxicity and abdominal pain in a CD patient is an indication for surgery[22].

Steroids and biological agents are often used but medical management including bowel rest and total parenteral nutrition often fail.

Subtotal colectomy, end ileostomy and subcutaneous placement of sigmoid stump or exteriorisation of the stump is associated with lower mortality than total colectomy in the management of toxic megacolon[73]. The decision to operate is based on clinical acumen as emergency surgery is guided by clinical signs of impending perforation rather than an exact diameter of colon demonstrated on CT or X-ray.

Dealing with the retained rectum or rectosigmoid is an important consideration after subtotal colectomy. There is no evidence that a second stoma or mucus fistula improves outcome. Subcutaneous placement of the stump has the lowest reported morbidity. Intraperitoneal placement is associated with a significantly higher risk of pelvic sepsis from stump blowout[74].

Cancer

The recent practice guidelines by Strong et al[15] on surgical management of CD provided strong recommendations for total proctocolectomy for patients with cancer, DALM, high grade dysplasia or multifocal low grade dysplasia. The rationale for total proctocolectomy is the high rate of metachronous cancers seen following segmental or subtotal colectomies associated with CD[75] - up to 40% for segmental resection, and 35% for subtotal colectomy. The mean time for development of metachronous cancer is approximately 7 years from initial surgery[75]. While the current guidelines recommend total proctocolectomy for CD associated colon cancer, a meta-analysis has shown increased risk of colon cancer but not rectal cancer in CD[26] and a total colectomy with surveillance of the remaining rectum is a reasonable option.

Dysplasia

The risk of cancer with high grade dysplasia is > 70%, and with low grade dysplasia about 30%-40%[76]. Approximately 50% of cancers in CD is associated with dysplasia[77].

Dysplasia is usually multifocal in CD colitis, and for this reason, segmental or subtotal colectomy for dysplasia is associated with high risk of developing subsequent malignancies. For patients assessed to be fit for surgery, total colectomy or proctocolectomy is recommended. High risk surgical candidates should have close endoscopic surveillance if the risks of surgery for dysplasia outweigh the benefits[76].

Dysplasia surveillance: CD colitis is associated with increased risk of cancer. Yearly colonoscopy is recommended for high risk CD patients who have one or more high risk factors including moderate to severe active inflammation, colonic stricture or dysplasia in the past 5 years, primary sclerosing cholangitis or family history of colorectal cancer < 50 years old. 3-yearly colonoscopy is recommended for intermediate risk CD patients including mild active colitis, inflammatory polyps or family history of colrectal cancer > 50 years old. Patients are low risk if there is no active inflammation (even with extensive colitis < 50% of colon), and these patients require 5-yearly colonoscopy[78].

Growth retardation

Paediatric CD may be complicated by growth retardation. Well-timed surgery for CD before puberty begins can help to control disease activity and improve nutritional status and reduce corticosteroid requirement[30]. However, early surgical recurrences are common due to more severe CD phenotype in younger patients, and this may limit the benefit of surgery[79].

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY IN PERIANAL CD

Perianal pathology occurs in 40%-80% of patients with CD[80]. Colonic and rectal CD phenotypes are associated with increased risk of perianal disease[81,82]. Anal fistulae in CD may be secondary to CD or associated with cryptoglandular origin. Anal cancers are rare in CD. There is not a significant increase in incidence of anal cancers in CD compared to the normal population.

SURGICAL OPTIONS FOR PERIANAL CD

Perianal fistulae and abscesses

Perianal disease causes significant impairment in the quality of life for CD patients[83]. 20% of CD patients require perianal surgical intervention at some stage[84] although the rate of surgery for perianal disease in CD is falling with increasing use of thiopurine and infliximab therapy[85].

The management of perianal abscesses in CD is the same as for the normal population - incision and drainage of abscess. Perianal abscesses may often be associated with complex fistulating disease or may be crypto-glandular. Endoanal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful to evaluate complex perianal disease.

For perianal fistulae, medical therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Surgery is reserved for patients who develop abscesses or sepsis. Anti-TNF therapy has been shown to be an effective treatment for closure of perianal fistulizing CD[65]. Infliximab or adalimumab step up therapy for CD guided by assessment of disease severity by anal ultrasound is associated with a high rate of fistula closure[86].

Low CD perianal fistulae may be treated by fistulotomy. Complex or high CD fistulae should be managed with placement of long-term setons. There is limited evidence for advancement flap closures, debridement, fistula plug and fibrin glue. The current gold standard is long-term setons with infliximab therapy. Closure rates of up to 60% for perianal CD fistulae have been reported,although results have been mixed[87]. If the patient is asymptomatic, however, there is no need for surgery or setons.

There is a very limited role for faecal diversion. As biological drugs may induce full regression in 80% of cases of anorectal disease[88], diversional stoma for perianal disease should be reserved for difficult cases refractory to medical therapy and drainage. There is a high likelihood that “temporary” faecal diversion to manage severe perianal CD is usually permanent[89,90]. Sauk et al[90] reported 49 patients who underwent faecal diversion for severe CD perianal disease of which 15/49 (30.6%) had reversal of stoma but ten of these (66.7%) required re-diversion of the faecal stream. Of the five patients who maintained intestinal continuity, three required further surgical interventions to control sepsis. The likelihood of restoration of intestinal continuity post faecal diversion is less than 20%[89]. In CD, perianal disease remains the most common reason for stoma[9].

Only patients with very severe anorectal involvement with CD, including anovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae, should have total proctocolectomy as anorectal CD usually responds well to biological agents with full regression of disease.

Anal cancer

Anal cancers are not common in CD and are difficult to diagnose. Only 61 cases of carcinomas arising in perineal fistulas associated with CD was reported in a systematic review in 2009[91].

In the majority of reported case, biopsies were only proven in 20% of cases[91]. A high index of suspicion for malignancy is required as biopsies of malignancy have a high false negative rate, with malignant cells deep within fistulae. In CD anal cancers, there is similar incidence of adenocarcinomas and squamous cell cancers.

The treatment modalities for anal cancers associated with CD is the same as with anal cancers in the normal population.

Anal fissures and tags

Anal fissures and bulky skin tags are common in CD. Avoid extensive surgery due to poor wound healing for skin tags and fissures. In the management of fissures, avoid lateral sphincterotomy. Management with lifestyle changes, botox and immunomodulators is preferable to surgery.

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN SURGERY FOR CD

Minimally invasive surgery

Laparoscopic colectomy is safe in the management of CD[92,93] and has short term benefits[94-96] including reduced blood loss, decreased rates of ileus and shorter length of stay[97,98] as well as decreased incisional hernia rates[95]. The main benefits of laparoscopic surgery are short term. Reoperation rates, endoscopic and radiologic recurrence are similar between both open and laparoscopic groups[99]. A potential long term benefit of laparoscopic surgery may include lower incidence of adhesional bowel obstructions[100].

Importantly, laparoscopic colectomy does not add to morbidity[67] and may reduce the risk of post-operative enteric fistula when compared with open surgery[101]. Laparoscopic surgery may be used successfully in complex CD[102] and recurrent CD[103]. While laparoscopic surgery has also been shown to be safe in patients with previous midline laparotomy for intestinal resection for CD, no significant advantage, except reduced wound infection rates, has been demonstrated[104].

The conversion rate for laparoscopic surgery in the setting of CD has been reported between 8.5%[103] to 13.4%[105]. The predictors for conversion include complex fistulating disease and the need to carry out multiple stricturoplasties[103].

Single incision laparoscopic surgery in CD has been shown to be safe, with results comparable with traditional laparoscopic procedures[106-108].

Anastomosis

End-to-end, side-to-side and end-to-side anastomoses have comparable recurrence rates despite early reports of differences, and all configurations are reasonable in the setting of CD[15].

Specifically for ileocolic anastomosis, however, a recent meta-analysis showed that a side-to-side stapled anastomosis is associated with decreased rates of anastomotic leak and decreased surgical recurrence[109].

The risk of anastomotic leak in CD varies from 3%[110] to 20%[69]. Leaks are usually diagnosed late in the postoperative period[111]. Colo-colonic anastomosis are associated with a higher risk of anastomotic complications when compared to entero-colic or enteroenteric anastomosis[69].

Major risk factors of anastomotic leak include low albumin[70], intra-abdominal abscess[35] corticosteroids[35], particularly patients on corticosteroid steroid dose equivalent to 20 mg of prednisolone or greater, with anastomotic complications reported between 20%[69].

Biologic treatment with infliximab or other anti-TNF therapy and immunomodulators pre-operatively have not been shown to have an increased risk of anastomotic leak[69,112], and should not be a contraindication to primary anastomosis.

Pouch

Pouches are not generally recommended for CD. The ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) is associated with high failure rates and poor functional outcomes[113], particularly for CD with NOD2 mutation which is associated with severe pouchitis[114,115]. Inflammation in the pouch is significantly higher for CD than for UC[116]. However, most cases of pouchitis can be managed with antibiotics, and those that are antibiotic resistant may be treated successfully with thiopurines alone[117]. Stricturing disease of the pouch also respond well to thiopurines but fistulising disease does not respond well to medical therapy and even with step up therapy to infliximab, the stoma rates are high[117].

The risk of malignancy within the IPAA associated with CD is small, with only a handful of case reports.

CONCLUSION

The management strategies of CD are largely dependent on phenotypic classification and indication. Advances in surgical management has reduced perioperative mortality rates to < 1%[118], with minimally invasive surgery shown to be safe in CD. However, unfortunately, improvements in surgical techniques have only been accompanied by modest improvements in surgical rates, recurrences and overall mortality.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare (refer to signed statement by the corresponding author).

Peer-review started: July 16, 2016

First decision: August 19, 2016

Article in press: September 28, 2016

P- Reviewer: Galanakis CG, Guerra F S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Bednarz W, Czopnik P, Wojtczak B, Olewiński R, Domosławski P, Spodzieja J. Analysis of results of surgical treatment in Crohn’s disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:998–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frolkis AD, Dykeman J, Negrón ME, Debruyn J, Jette N, Fiest KM, Frolkis T, Barkema HW, Rioux KP, Panaccione R, et al. Risk of surgery for inflammatory bowel diseases has decreased over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:996–1006. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tøttrup A, Erichsen R, Sværke C, Laurberg S, Srensen HT. Thirty-day mortality after elective and emergency total colectomy in Danish patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000823. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mühe E, Gall FP, Hager T, Angermann B, Söhnlein B, Schier F, Hermanek P. [Surgery of Crohn’s disease: a study of 155 patients after intestinal resection (author’s transl)] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1981;106:165–170. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1070278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goyer P, Alves A, Bretagnol F, Bouhnik Y, Valleur P, Panis Y. Impact of complex Crohn’s disease on the outcome of laparoscopic ileocecal resection: a comparative clinical study in 124 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:205–210. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819c9c08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haneda S, Ohnuma S, Musha H, Morikawa T, Nagao M, Abe T, Tanaka N, Kudoh K, Sasaki H, Kohyama A, et al. Outcome of surgical treatment for crohn’s disease. Eur Surg Res. 2014;52:195–196. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kono E, Haneda S, Ohnuma S, Musha H, Morikawa T, Nagao M, Abe T, Tanaka N, Kudo K, Sasaki H, et al. Long-term outcome of intestinal failure requiring home parenteral nutrition in patients with crohn’s disease. Eur Surg Res. 2014;52:220–221. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elriz K, Palascak-Juif V, Joly F, Seguy D, Beau P, Chambrier C, Boncompain M, Fontaine E, Laharie D, Savoye G, et al. Crohn’s disease patients with chronic intestinal failure receiving long-term parenteral nutrition: a cross-national adult study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:931–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuehn F, Nixdorf M, Klar E. The role of surgery in Crohn’s disease: Single center experience from 2005-2014. Gastroenterology. 2015;1:S1167–S1168. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juneja M, Baidoo L, Schwartz MB, Barrie A, Regueiro M, Dunn M, Binion DG. Geriatric inflammatory bowel disease: phenotypic presentation, treatment patterns, nutritional status, outcomes, and comorbidity. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2408–2415. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon YS, Yu CS, Yang SK, Yoon SN, Lim SB, Kim JC. Intra-abdominal fistulas in surgically treated Crohn’s disease patients. World J Surg. 2010;34:1924–1929. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatch Q, Johnson E, Martin M, Steele S. Pregnancy and crohn’s disease: An analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample. J Surg Res. 2014;186:626. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leal RF, Ward M, Ayrizono Mde L, de Paiva NM, Bellaguarda E, Rossi DH, Vieira NP, Fagundes JJ, Rodrigues Coy CS. Free peritoneal perforation in a patient with Crohn’s disease - Report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:322–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenstein AJ, Sachar DB, Mann D, Lachman P, Heimann T, Aufses AH. Spontaneous free perforation and perforated abscess in 30 patients with Crohn’s disease. Ann Surg. 1987;205:72–76. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198701000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strong S, Steele SR, Boutrous M, Bordineau L, Chun J, Stewart DB, Vogel J, Rafferty JF; Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Surgical Management of Crohn’s Disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:1021–1036. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Frequency of glucocorticoid resistance and dependency in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1994;35:360–362. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modigliani R. Immunosuppressors for inflammatory bowel disease: how long is long enough? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:251–257; discussion 158. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200008000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman PA, Wolfson D, Barkin JS. Medical management of Crohn’s disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2007;20:269–281. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daperno M, Sostegni R, Rocca R. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn’s disease: how (un-)common is it and how to tackle it? Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:721–722. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robert JR, Sachar DB, Greenstein AJ. Severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage in Crohn’s disease. Ann Surg. 1991;213:207–211. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199103000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenstein AJ, Sachar DB, Gibas A, Schrag D, Heimann T, Janowitz HD, Aufses AH. Outcome of toxic dilatation in ulcerative and Crohn’s colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:137–143. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198504000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Autenrieth DM, Baumgart DC. Toxic megacolon. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:584–591. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kassam Z, Belga S, Roifman I, Hirota S, Jijon H, Kaplan GG, Ghosh S, Beck PL. Inflammatory bowel disease cause-specific mortality: a primer for clinicians. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2483–2492. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jess T, Loftus EV, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Tremaine WJ, Melton LJ, Munkholm P, Sandborn WJ. Survival and cause specific mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a long term outcome study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-2004. Gut. 2006;55:1248–1254. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.079350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laukoetter MG, Mennigen R, Hannig CM, Osada N, Rijcken E, Vowinkel T, Krieglstein CF, Senninger N, Anthoni C, Bruewer M. Intestinal cancer risk in Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:576–583. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Roon AC, Reese G, Teare J, Constantinides V, Darzi AW, Tekkis PP. The risk of cancer in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:839–855. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0848-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribeiro MB, Greenstein AJ, Sachar DB, Barth J, Balasubramanian S, Harpaz N, Heimann TM, Aufses AH. Colorectal adenocarcinoma in Crohn’s disease. Ann Surg. 1996;223:186–193. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199602000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scaringi S, Di Martino C, Zambonin D, Fazi M, Canonico G, Leo F, Ficari F, Tonelli F. Colorectal cancer and Crohn’s colitis: clinical implications from 313 surgical patients. World J Surg. 2013;37:902–910. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1922-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindström L, Lapidus A, Ost A, Bergquist A. Increased risk of colorectal cancer and dysplasia in patients with Crohn’s colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1392–1397. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822bbcc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kglmeier J, Croft N. How to Prevent Growth Failure in Children. Clinical Dilemmas in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Wiley-Blackwell, 2007: 150-152 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atreja A, Patel SS, Colombel JF, Sands BE. Validation of simplified stricture severity score (4s) to predict the need for surgery in patients with stricturing crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;1:S61–S62. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jambaulikar GD, Armbruster S, Ally MR, Deising A, Cross R. Factors associated with repeat endoscopic balloon dilation and surgery after endoscopic balloon dilation for the treatment of stricturing crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;1:S–462. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bamford R, Hay A, Kumar D. Number of strictures is predictive of recurrent surgical intervention in a paediatric population with Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:34. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk Factors for Surgery and Postoperative Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease. Ann Surg. 2000;231:38. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tzivanakis A, Singh JC, Guy RJ, Travis SP, Mortensen NJ, George BD. Influence of risk factors on the safety of ileocolic anastomosis in Crohn’s disease surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:558–562. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318247c433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maguire L, Olariu A, Hicks C, Hodin R, Bordeianou L. Does TNF inhibitor treatment prior to surgery for small bowel crohn’s disease modulate disease severity and minimize surgical intervention? Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:e81–e82. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salem A, Saber K, Elnaamei H, Ourfali A. Surgery for isolated terminal ileum Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:365. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Folaranmi S, Rakoczy G, Bruce J, Humphrey G, Bowen J, Morabito A, Kapur P, Morecroft J, Craigie R, Cserni T. Ileocaecal valve: how important is it? Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:613–615. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bakkevold KE. Nipple Valve Anastomosis for Preventing Recurrence of Crohn Disease in the Neoterminal Ileum after Ileocolic Resection: A Prospective Pilot Study. Scandinavian J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:293–299. doi: 10.1080/003655200750024173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fazi M, Giudici F, Luceri C, Pronestì M, Tonelli F. Long-term Results and Recurrence-Related Risk Factors for Crohn Disease in Patients Undergoing Side-to-Side Isoperistaltic Strictureplasty. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:452–460. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.4552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellolio F, Cohen Z, MacRae HM, O’Connor BI, Victor JC, Huang H, McLeod RS. Strictureplasty in selected Crohn’s disease patients results in acceptable long-term outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:864–869. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318258f5cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell L, Ambe R, Weaver J, Marcus SM, Cagir B. Comparison of conventional and nonconventional strictureplasties in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:714–726. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31824f875a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prabhakar LP, Laramee C, Nelson H, Dozois RR. Avoiding a stoma: role for segmental or abdominal colectomy in Crohn’s colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:71–78. doi: 10.1007/BF02055685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tekkis PP, Purkayastha S, Lanitis S, Athanasiou T, Heriot AG, Orchard TR, Nicholls RJ, Darzi AW. A comparison of segmental vs subtotal/total colectomy for colonic Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:82–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Broering DC, Eisenberger CF, Koch A, Bloechle C, Knoefel WT, Dürig M, Raedler A, Izbicki JR. Strictureplasty for large bowel stenosis in Crohn’s disease: quality of life after surgical therapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:81–87. doi: 10.1007/s003840000278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nanda KS, Courtney WA, Keegan D, Byrne K, Nolan B, Mulcahy H, O’Donoghue DP, Doherty GA. Avoidance of repeat surgery with endoscopic balloon dilatation of anastomotic strictures in crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;1:S356–S357. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rondonotti E, Sunada K, Yano T, Paggi S, Yamamoto H. Double-balloon endoscopy in clinical practice: where are we now? Dig Endosc. 2012;24:209–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halloran BP, Melmed GY, Jamil LH, Lo SK, Vasiliauskas EA, Mann NK. Double balloon enteroscopy-assisted stricture dilation delays surgery in patients with small bowel crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;1:AB280. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirai F, Beppu T, Takatsu N, Yano Y, Ninomiya K, Ono Y, Hisabe T, Matsui T. Long-term outcome of endoscopic balloon dilation for small bowel strictures in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:545–551. doi: 10.1111/den.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirai F, Beppu T, Sou S, Seki T, Yao K, Matsui T. Endoscopic balloon dilatation using double-balloon endoscopy is a useful and safe treatment for small intestinal strictures in Crohn’s disease. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:200–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greener T, Shapiro R, Klang E, Rozendorn N, Eliakim R, Ben-Horin S, Amitai MM, Kopylov U. Clinical Outcomes of Surgery Versus Endoscopic Balloon Dilation for Stricturing Crohn’s Disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:1151–1157. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Y, Stocchi L, Shen B, Liu X, Remzi FH. Salvage surgery after failure of endoscopic balloon dilatation versus surgery first for ileocolonic anastomotic stricture due to recurrent Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1418–1425; discussion 1425. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Branche J, Attar A, Vernier-Massouille G, Bulois P, Colombel JF, Bouhnik Y, Maunoury V. Extractible self-expandable metal stent in the treatment of Crohn’s disease anastomotic strictures. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E325–E326. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loras C, Pérez-Roldan F, Gornals JB, Barrio J, Igea F, González-Huix F, González-Carro P, Pérez-Miranda M, Espinós JC, Fernández-Bañares F, et al. Endoscopic treatment with self-expanding metal stents for Crohn’s disease strictures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:833–839. doi: 10.1111/apt.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levine RA, Wasvary H, Kadro O. Endoprosthetic management of refractory ileocolonic anastomotic strictures after resection for Crohn’s disease: report of nine-year follow-up and review of the literature. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:506–512. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cullen G, Vaughn B, Ahmed A, Peppercorn MA, Smith MP, Moss AC, Cheifetz AS. Abdominal phlegmons in Crohn’s disease: outcomes following antitumor necrosis factor therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:691–696. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dotson JL, Kappelman MD, Chisolm DJ, Crandall WV. Racial disparities in readmission, complications, and procedures in children with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:801–808. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poritz LS, Koltun WA. Percutaneous drainage and ileocolectomy for spontaneous intraabdominal abscess in Crohn’s disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:204–208. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bermejo F, Garrido E, Chaparro M, Gordillo J, Mañosa M, Algaba A, López-Sanromán A, Gisbert JP, García-Planella E, Guerra I, et al. Efficacy of different therapeutic options for spontaneous abdominal abscesses in Crohn’s disease: are antibiotics enough? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1509–1514. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee H, Kim YH, Kim JH, Chang DK, Son HJ, Rhee PL, Kim JJ, Paik SW, Rhee JC. Nonsurgical treatment of abdominal or pelvic abscess in consecutive patients with Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:659–664. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jawhari A, Kamm MA, Ong C, Forbes A, Bartram CI, Hawley PR. Intra-abdominal and pelvic abscess in Crohn’s disease: results of noninvasive and surgical management. Br J Surg. 1998;85:367–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gutierrez A, Lee H, Sands BE. Outcome of Surgical Versus Percutaneous Drainage of Abdominal and Pelvic Abscesses in Crohn’s Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2283–2289. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang W, Zhu W, Li Y, Zuo L, Wang H, Li N, Li J. The respective role of medical and surgical therapy for enterovesical fistula in Crohn’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:708–711. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poritz LS, Gagliano GA, McLeod RS, MacRae H, Cohen Z. Surgical management of entero and colocutaneous fistulae in Crohn’s disease: 17 year’s experience. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:481–485; discussion 486. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0580-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Amiot A, Setakhr V, Seksik P, Allez M, Treton X, De Vos M, Laharie D, Colombel JF, Abitbol V, Reimund JM, et al. Long-term outcome of enterocutaneous fistula in patients with Crohn’s disease treated with anti-TNF therapy: a cohort study from the GETAID. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1443–1449. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fernandez-Blanco I, Taxonera C, Bastida G, Garcia-Sanchez V, Gomez R, Marin-Jimenez I, Flores EI, Gisbert JP, Barreiro-De Acosta M, Bermejo F, et al. Outcomes of surgical treatment of entero-urinary fistulas in crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;1:S–599. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Melton GB, Stocchi L, Wick EC, Appau KA, Fazio VW. Contemporary surgical management for ileosigmoid fistulas in Crohn’s disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:839–845. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0817-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shental O, Tulchinsky H, Greenberg R, Klausner JM, Avital S. Positive histological inflammatory margins are associated with increased risk for intra-abdominal septic complications in patients undergoing ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1125–1130. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318267c74c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.El-Hussuna A, Andersen J, Bisgaard T, Jess P, Henriksen M, Oehlenschlager J, Thorlacius-Ussing O, Olaison G. Biologic treatment or immunomodulation is not associated with postoperative anastomotic complications in abdominal surgery for Crohn’s disease. Scandinavian J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:662–668. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.660540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riss S, Bittermann C, Zandl S, Kristo I, Stift A, Papay P, Vogelsang H, Mittlböck M, Herbst F. Short-term complications of wide-lumen stapled anastomosis after ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease: who is at risk? Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:e298–e303. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Papi C, Gili L, Tarquini M, Antonelli G, Capurso L. Infliximab for severe recurrent Crohn’s disease presenting with massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:238–241. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200303000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Belaiche J, Van Kemseke C, Louis E. Use of the enteroscope for colo-ileoscopy: low yield in unexplained lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 1999;31:298–301. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Block GE, Moossa AR, Simonowitz D, Hassan SZ. Emergency colectomy for inflammatory bowel disease. Surgery. 1977;82:531–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Trickett JP, Tilney HS, Gudgeon AM, Mellor SG, Edwards DP. Management of the rectal stump after emergency sub-total colectomy: which surgical option is associated with the lowest morbidity? Colorect Dis. 2005;7:519–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maser EA, Sachar DB, Kruse D, Harpaz N, Ullman T, Bauer JJ. High rates of metachronous colon cancer or dysplasia after segmental resection or subtotal colectomy in Crohn’s colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1827–1832. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318289c166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kiran RP, Nisar PJ, Goldblum JR, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Shen B, Lavery IC. Dysplasia associated with Crohn’s colitis: segmental colectomy or more extended resection? Ann Surg. 2012;256:221–226. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825f0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maykel JA, Hagerman G, Mellgren AF, Li SY, Alavi K, Baxter NN, Madoff RD. Crohn’s colitis: the incidence of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in surgical patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:950–957. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0555-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, Dunlop MG, Thomas HJ, Evans GD, Eaden JA, Rutter MD, Atkin WP, Saunders BP, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002) Gut. 2010;59:666–689. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.179804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heuschkel R, Salvestrini C, Beattie RM, Hildebrand H, Walters T, Griffiths A. Guidelines for the management of growth failure in childhood inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:839–849. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Makowiec F, Jehle EC, Becker HD, Starlinger M. Perianal abscess in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:443–450. doi: 10.1007/BF02258390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Louis E, Van Kemseke C, Reenaers C. Necessity of phenotypic classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25 Suppl 1:S2–S7. doi: 10.1016/S1521-6918(11)70003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lopez J, Konijeti GG, Nguyen DD, Sauk J, Yajnik V, Ananthakrishnan AN. Natural history of Crohn’s disease following total colectomy and end ileostomy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1236–1241. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mahadev S, Young JM, Selby W, Solomon MJ. Quality of life in perianal Crohn’s disease: what do patients consider important? Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:579–585. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182099d9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eglinton T, Reilly M, Chang C, Barclay M, Frizelle F, Gearry R. Ileal disease is associated with surgery for perianal disease in a population-based Crohn’s disease cohort. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1103–1109. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chhaya V, Saxena S, Cecil E, Subramanian V, Curcin V, Majeed A, Pollok R. Have perianal surgery rates decreased with the rise in thiopurine use in Crohn’s disease? Gut. 2014;63:A176. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wiese DM, Beaulieu D, Slaughter JC, Horst S, Wagnon J, Duley C, Annis K, Nohl A, Herline A, Muldoon R, et al. Use of Endoscopic Ultrasound to Guide Adalimumab Treatment in Perianal Crohn’s Disease Results in Faster Fistula Healing. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1594–1599. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Steele SR, Kumar R, Feingold DL, Rafferty JL, Buie WD. Practice parameters for the management of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1465–1474. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823122b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coscia M, Gentilini L, Laureti S, Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Campieri M, Calabrese C, Poggioli G. Risk of permanent stoma in extensive Crohn’s colitis: the impact of biological drugs. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1115–1122. doi: 10.1111/codi.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hong MK, Craig Lynch A, Bell S, Woods RJ, Keck JO, Johnston MJ, Heriot AG. Faecal diversion in the management of perianal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:171–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sauk J, Nguyen D, Yajnik V, Khalili H, Konijeti G, Hodin R, Bordeianou L, Shellito P, Sylla P, Korzenik J, et al. Natural history of perianal Crohn’s disease after fecal diversion. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2260–2265. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thomas M, Bienkowski R, Vandermeer TJ, Trostle D, Cagir B. Malignant transformation in perianal fistulas of Crohn’s disease: a systematic review of literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:66–73. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dasari BV, McKay D, Gardiner K. Laparoscopic versus Open surgery for small bowel Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(1):CD006956. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006956.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Diamond IR, Langer JC. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open ileocolic resection for adolescent Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33:543–547. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee Y, Fleming FJ, Deeb AP, Gunzler D, Messing S, Monson JRT. A laparoscopic approach reduces short-term complications and length of stay following ileocolic resection in Crohn’s disease: an analysis of outcomes from the NSQIP database. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:572–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Patel SV, Patel SV, Ramagopalan SV, Ott MC. Laparoscopic surgery for Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of perioperative complications and long term outcomes compared with open surgery. BMC Surg. 2013;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kotze P, Abou-Rejaile V, De Barcelos I, Miranda E, Martins J, Rocha J, Kotze L. Complication rates after bowel resections for crohn’s disease: A brazilian single-center comparison between laparoscopic and conventional surgery. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:S58–S59. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Holubar SD, Dozois EJ, Privitera A, Cima RR, Pemberton JH, Young-Fadok T, Larson DW. Laparoscopic surgery for recurrent ileocolic Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1382–1386. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tilney HS, Constantinides VA, Heriot AG, Nicolaou M, Athanasiou T, Ziprin P, Darzi AW, Tekkis PP. Comparison of laparoscopic and open ileocecal resection for Crohn’s disease: a metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1036–1044. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stocchi L, Milsom JW, Fazio VW. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic versus open ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease: Follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. Surgery. 2008;144:622–628. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rosin D, Zmora O, Hoffman A, Khaikin M, Bar Zakai B, Munz Y, Shabtai M, Ayalon A. Low incidence of adhesion-related bowel obstruction after laparoscopic colorectal surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:604–607. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Masoomi H, Carmichael JC, Mills S, Pigazzi A, Stamos MJ. Predictive risk factors of early postoperative enteric fistula in colon and rectal surgery. Am Surg. 2013;79:1058–1063. doi: 10.1177/000313481307901021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kessler H, Hohenberger W. Laparoscopy as primary access to surgery for crohn’s disease: Results from a single center. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:e175. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chaudhary B, Glancy D, Dixon AR. Laparoscopic surgery for recurrent ileocolic Crohn’s disease is as safe and effective as primary resection. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1413–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aytac E, Stocchi L, Remzi FH, Kiran PR. Is Laparoscopic resection for recurrent disease beneficial in patients with previous intestinal resection for crohn’s disease through midline laparotomy? A case-matched study. Gastroenterology. 2012;1:S1072. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.de Campos-Lobato LF, Alves-Ferreira PC, Geisler DP, Kiran RP. Benefits of laparoscopy: does the disease condition that indicated colectomy matter? Am Surg. 2011;77:527–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Saites CG, Bairdain S, Lien C, Turner C, Gray F, Johnson V, Zurakowski D, Linden BC. Single incision Vs. Conventional laparoscopic ileocecectomy in pediatric crohn disease. Journal of Surgical Research Conference: 8th Annual Academic Surgical Congress of the Association for Academic Surgery, AAS and the Society of University Surgeons, SUS New Orleans, LA United States Conference Start, 2013: 179; [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rijcken E, Mennigen R, Argyris I, Senninger N, Bruewer M. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery for ileocolic resection in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:140–146. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823d0e0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lai CW, Edwards TJ, Clements DM, Coleman MG. Single port laparoscopic right colonic resection using a ‘vessel-first’ approach. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1138–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.He X, Chen Z, Huang J, Lian L, Rouniyar S, Wu X, Lan P. Stapled side-to-side anastomosis might be better than handsewn end-to-end anastomosis in ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1544–1551. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, Young-Fadok T, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Sandborn WJ. Early Postoperative Complications are not Increased in Patients with Crohn’s Disease Treated Perioperatively with Infliximab or Immunosuppressive Therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:878–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hyman N, Manchester TL, Osler T, Burns B, Cataldo PA. Anastomotic leaks after intestinal anastomosis: it’s later than you think. Ann Surg. 2007;245:254–258. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225083.27182.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Myrelid P, Marti-Gallostra M, Ashraf S, Sunde ML, Tholin M, Oresland T, Lovegrove RE, Tøttrup A, Kjaer DW, George BD. Complications in surgery for Crohn’s disease after preoperative antitumour necrosis factor therapy. Br J Surg. 2014;101:539–545. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yamamoto T, Watanabe T. Surgery for luminal Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:78–90. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sehgal R, Berg A, Polinski JI, Hegarty JP, Lin Z, McKenna KJ, Stewart DB, Poritz LS, Koltun WA. Genetic risk profiling and gene signature modeling to predict risk of complications after IPAA. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:239–248. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823e2d18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sehgal R, Berg A, Hegarty JP, Kelly AA, Lin Z, Poritz LS, Koltun WA. NOD2/CARD15 mutations correlate with severe pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1487–1494. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f22635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Le Q, Melmed G, Dubinsky M, McGovern D, Vasiliauskas EA, Murrell Z, Ippoliti A, Shih D, Kaur M, Targan S, et al. Surgical outcome of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis when used intentionally for well-defined Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:30–36. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Haveran LA, Sehgal R, Poritz LS, McKenna KJ, Stewart DB, Koltun WA. Infliximab and/or azathioprine in the treatment of Crohn’s disease-like complications after IPAA. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:15–20. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181fc9f04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lesperance K, Martin MJ, Lehmann R, Brounts L, Steele SR. National trends and outcomes for the surgical therapy of ileocolonic Crohn’s disease: a population-based analysis of laparoscopic vs. open approaches. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1251–1259. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]