Abstract

We previously identified the long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) MSNP1AS (moesin pseudogene 1, antisense) as a functional element revealed by genome wide significant association with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). MSNP1AS expression was increased in the postmortem cerebral cortex of individuals with ASD and particularly in individuals with the ASD-associated genetic markers on chromosome 5p14.1. Here, we mimicked the overexpression of MSNP1AS observed in postmortem ASD cerebral cortex in human neural progenitor cell lines to determine the impact on neurite complexity and gene expression. ReNcell CX and SK-N-SH were transfected with an overexpression vector containing full-length MSNP1AS. Neuronal complexity was determined by the number and length of neuronal processes. Gene expression was determined by strand-specific RNA sequencing. MSNP1AS overexpression decreased neurite number and neurite length in both human neural progenitor cell lines. RNA sequencing revealed changes in gene expression in proteins involved in two biological processes: protein synthesis and chromatin remodeling. These data indicate that overexpression of the ASD-associated lncRNA MSNP1AS alters the number and length of neuronal processes. The mechanisms by which MSNP1AS overexpression impacts neuronal differentiation may involve protein synthesis and chromatin structure. These same biological processes are also implicated by rare mutations associated with ASD, suggesting convergent mechanisms.

Keywords: lncRNA, RNA-sequencing, autism, long noncoding RNA, noncoding RNA, neuronal progenitor

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by deficits in social communication and repetitive behaviors with restricted interests [1,2]. Highly penetrant, rare, de novo loss of function mutations has been associated with ASD, and many of the associated genes converge upon the biological processes of protein synthesis and chromatin structure [3,4]. However, 40% of the heritability of ASD resides in common genetic variants [5,6]. The first reported common genetic variants with genome-wide significant association with ASD mapped to a small cluster of chromosome 5p14.1, including the common genetic variant rs4307059 with ASD association of p = 10−10 [7]. The same rs4307059 allele was also identified as a predictor or stereotyped conversation and poorer communication skills in a population-based sample of >7000 individuals [8], suggesting that rs4307059 may be a quantitative trait locus for social communication phenotypes. We identified a 3.9 kb long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) that is transcribed directly at the site of the chromosome 5p14.1 ASD association signal [9]. The lncRNA is encoded by the opposite (anti-sense) strand of moesin pseudogene 1 (MSNP1), and is thus designated MSNP1AS (moesin pseudogene 1, anti-sense). Expression of MSNP1AS in the postmortem temporal cortex is increased 12.7-fold in individuals with ASD and increased 22-fold in individuals with the rs4307059 risk allele [9]. Thus, our discovery revealed an lncRNA, which based on the highly significant genetic association findings [7], contributes to ASD risk [9].

MSNP1AS is 94% identical and anti-sense to the X chromosome transcript MSN, which encodes a protein (moesin) that regulates neuronal architecture [10,11,12,13,14]. The lncRNA MSNP1AS binds MSN and its over-expression in cell lines caused significant decreases in moesin protein [9], which influences neuronal process stability [12]. Based on these observations, a direct hypothesis is that overexpression of MSNP1AS in progenitors of cortical projection neurons will decrease neuronal complexity, consistent with observations of decreased long distance connectivity observed in the cerebral cortex of individuals with ASD [15,16,17,18,19,20]. We tested this hypothesis by transfecting differentiating human neural progenitor cells with an overexpression vector that drives full-length MSNP1AS and directly measuring the number and length of the neurites. We demonstrated previously that one mechanism by which MSNP1AS may alter neuronal complexity is by decreasing the expression of moesin protein [9]. However, alternative hypotheses about the mechanism(s) of the ASD-associated lncRNA MSNP1AS had not been tested. While our previous experiments revealed that MSNP1AS over-expression decreased expression of moesin protein [9], it was not yet clear if MSNP1AS regulated the expression of the MSN transcript or if MSNP1AS over-expression altered the expression of other genes. Therefore, we performed unbiased RNA sequencing on differentiating human neural progenitor cells to determine the impact of increased MSNP1AS on gene expression. These experiments mimic the increased expression of MSNP1AS observed in postmortem brains of individuals with ASD and reveal multiple mechanisms by which the lncRNA MSNP1AS may contribute to altered neuronal architecture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

The human neural progenitor cell lines SK-N-SH cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) and ReNcell CX cells (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) were cultured according to the manufacturer’s protocols and maintained in a 75 cm2 flask at 37 °C and 5% CO2. When cells were 75% confluent, the human neural progenitor cells were subcultured to a density of 1 × 106 cells per 75 cm2 flask for harvests 24 h post-transfection, and 5 × 105 cells per 75 cm2 flask for harvests 72 h post-transfection.

2.2. Transfection of Over-Expression Constructs

Full-length MSNP1AS was inserted into pIRES2-AcGFP (Clontech) [9], a mammalian over-expression construct. Each experiment was made up of one pIRES2-AcGFP negative control transfection and one pIRES2-AcGFP-MSNP1AS transfection. Cells were transfected using Amaxa Nucleofector (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) technology, using 2 µg of vector per well, and subcultured into 6-well plates. One milliliter of fresh prewarmed media was added to each well and the cells were centrifuged twice at 130× g for 10 min for the SK-N-SH cells and 300× g for 5 min for the ReNcell CX cells with PBS washes of 7 mL and 4 mL, respectively. The cell pellet was resuspended in Nucleofector solution containing a supplement using 1 × 106 cells per well. One hundred microliters of cell/Nucleofector solution was added to a new cuvette and placed in the Amaxa Nucleofector using the T-16 program. Five hundred microliters of fresh prewarmed media was added to the cuvette, mixed, and transferred to the well with a disposable pipet. A two mL culture medium was added to the transfected cells in the 6-well plate. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 until harvest. Each experiment was repeated four times.

2.3. Imaging

At 24 and 72 h post-transfection, human neural progenitors were viewed using an Olympus CKX41 inverted microscope and an attached Q Imaging QICAM Fast 1394 Digital Camera captured digital images. Randomly selected fields of the 6-well plate were imaged. Three randomly selected fields were imaged in each experiment. Neurite length and number of each GFP-positive cell within the field were quantified using Autoneuron software. Only neurons unobstructed by other neurons or debris were analyzed. Statistical significance was calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test.

2.4. Neural Progenitor Cell Harvest for RNA Purification

After 24 h and 72 h, the culture medium was removed and discarded. The cells were washed with one mL of PBS wash and the PBS wash was aspirated. One mL of Trypsin/EDTA solution for SK-N-SH cells and Accutase for ReNcell CX cells was added to each well and the cells were incubated for 4 min. Five mL of cell type-specific medium was added and cells were triturated and transferred to 15 mL conical tubes. SK-N-SH cells were centrifuged at 130× g for 10 min and ReNcell CX cells were centrifuged at 300× g for 5 min. The supernatant was aspirated and 5 mL of PBS added. The cell pellet was triturated and centrifuged at 130× g for 10 min and 300× g for 5 min respectively. The PBS wash was aspirated and 1 mL of fresh PBS was added. Half of the solution was transferred to each of two 1.5 mL eppendorf tubes. The tubes were centrifuged at 4 °C at 130× g for 10 min for SK-N-SH cells and 300× g for 5 min for ReNcell CX cells. The supernatant was decanted and the cell pellets were frozen at −80 °C.

2.5. RNA Purification

The Qiagen RNEasy kit was used to isolate total RNA using vacuum technology according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The RNA was eluted with 35 microliters of RNAse-free water and quantified using the NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (v3.1.2; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The RNA was stored at −20 °C.

2.6. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

To confirm overexpression of MSNP1AS, consistent with the ~12-fold increase observed in postmortem brains of individuals with ASD, cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for qRT-PCR protocol (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Five hundred nanograms of RNA were used to make one and a half reaction volumes (35 μL) of cDNA. The cDNA was stored at −20 °C. The qRT-PCR protocol described in Kerin et al. [9] was used to validate over-expression of MSNP1AS.

2.7. Construction of Strand-Specific, Ribosomal RNA Depleted RNA Sequencing Libraries

Directional RNA-Seq libraries were prepared for Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing using the Stranded Total TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation kit with Ribo-Zero Gold (Illumina) using the manufacturer’s protocol using the Hamilton Starlet Liquid Handling robot. One nanogram of RNA was used for each sample. In brief, Ribo-Zero was used to deplete cytoplasmic and mitochondrial rRNA from total RNA. The depleted RNA was fragmented and primed with random hexamers to synthesize first strand cDNA using Superscript II (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Next, the second strand was synthesized, incorporating dUTP in place of dTTP. A single “A” base was added to the 3′ ends of the fragments and the indexed adaptors were ligated to the ends of the ds cDNA to prepare them for hybridization onto the flow cell. PCR was used to selectively enrich the fragments with ligated adapters and to amplify the amount of DNA in the library. The libraries were produced in a 96-well format and quality controlled using the Agilent Technologies 2200 TapeStation Instrument. Libraries were pooled (four samples per lane) and sequenced on Illumina HiSeq 2000 to a targeted depth, generating an average of 20 million paired-end 50-cycle reads for each sample (Table S1).

2.8. Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using TopHat (version 2.0.10; https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml) [21] to align the Illumina short reads against the reference human genome ENSEMBL GrCH38 version 81. Sequence alignments were generated as BAM files [22], and then Cuffdiff (version 2.2.1; http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/) [23] was used to summarize the gene expression values as FPKM measures. The gene expression of samples with MSNP1AS over-expression were compared to the gene expression of the negative control experiment samples to find other differentially-expressed genes. Cuffdiff was also used to calculate the expression fold change, p-values and FDR values. Genes with p < 0.05 were used as the input for DAVID (version 6.7; Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., Frederick, MD, USA) functional annotation [24,25].

3. Results

3.1. Overexpression of MSNP1AS Decreased Neurite Number and Length in SK-N-SH and ReNcell CX Human Neural Progenitor Cells

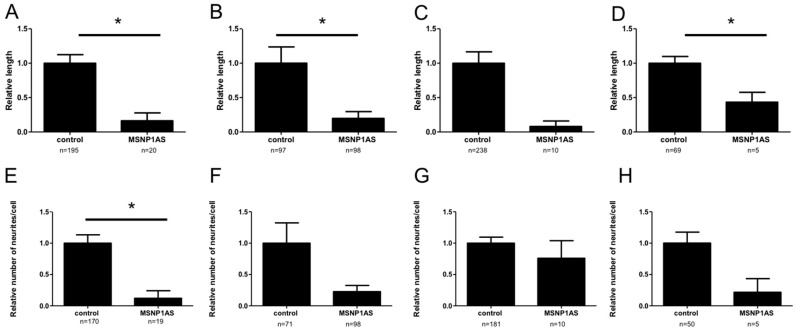

To mimic the overexpression of MSNP1AS observed in postmortem brains of individuals with ASD, MSNP1AS was overexpressed ~50-fold (Table S2) in human neural progenitor cells using a human overexpression vector containing the full length MSNP1AS transcript. Human neural progenitor cells that overexpressed MSNP1AS had decreased neurite length compared to human neural progenitor cells transfected with the empty vector control (Figure 1 and Figure 2). In SK-N-SH cells, neurite length was reduced 6-fold (p = 1.1 × 10−2) at 24 h post-transfection and 5-fold (p = 6.0 × 10−4) at 72 h post-transfection in neural progenitor cells transfected with the MSNP1AS over-expression vector compared to controls (Figure 2A,B). Similarly, MSNP1AS overexpression in ReNcell CX human neural progenitor cells caused a significant decrease in neurite length at 72 h post-transfection by 12.5-fold (p = 2.5 × 10−2), but the decreased neurite length observed at 24 h post-transfection was not significant (2.3-fold; p = 2.9 × 10−1) (Figure 2C,D).

Figure 1.

Representative ReNcell CX cells at 24 h post-transfection. The human neural progenitor cells were transfected with (A) an empty vector control or (B) the MSNP1AS overexpression vector. For each experiment, the transfection of MSNP1AS over-expression or control vector was repeated four times. Three randomly selected fields from each of the four replicates were imaged and all isolated GFP-positive cells within the imaged fields were examined for neurite length and neurite number using Autoneuron software.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of MSNP1AS decreases neurite number and length. SK-N-SH cells that overexpressed MSNP1AS had decreased neurite length after (A) 24 h and (B) 72 h. ReNcell CX cells that overexpressed MSNP1AS also had decreased neurite length after (D) 72 h but the decreased neurite length after (C) 24 h was not significant. SK-N-SH cells that overexpressed MSNP1AS had fewer neurites per cell after (E) 24 h and a trend toward reduced neurites per cell after (F) 72 h. ReNcell CX cells that overexpressed MSNP1AS also had trend toward fewer neurites per cell after (H) 72 h, but the neurite number decrease after (G) 24 h was not significant (* p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test).

MSNP1AS overexpression also caused a reduction in the number of neurites in human neural progenitor cells. In SK-N-SH cells, MSNP1AS overexpression caused an 8.3-fold reduction in neurite number at 24 h post-transfection (p = 2.1 × 10−2) and a trend toward reduced neurite number at 72 h post-transfection (4.4-fold; p = 6.2 × 10−2) (Figure 2E,F). Similarly, MSNP1AS overexpression in ReNcell CX cells caused a trend toward fewer neurite number at 72 h post-transfection (4.6-fold; p = 1.0 × 10−1), but the neurite number decrease at 24 h post-transfection was not significant (1.3-fold; p = 7.9 × 10−1) (Figure 2G,H).

3.2. Genome-Wide Changes in Gene Expression Following MSNP1AS Overexpression in Human Neural Progenitor Cells

Changes in the transcriptome caused by MSNP1AS overexpression may provide insight into the mechanisms by which an increase of MSNP1AS influences neuronal architecture. Therefore, RNA sequencing was used to perform genome-wide transcriptome profiling on the two human neural progenitor cells lines SK-N-SH and ReNcell CX cells with and without MSNP1AS overexpression. For all experiments, the average number of reads ranged from 14–29 million with 96% of the reads mapping to the genome (Table S1). No change in gene expression survived Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons in any of the experiments (Table S3). However, each of the experiments revealed 100–400 genes with nominally significant changes in gene expression (p < 0.05). All downstream analyses were performed with the sets of genes that had significant (p < 0.05) changes in expression following MSNP1AS over-expression. Differential gene expression analysis in SK-N-SH cells revealed 157 differentially expressed genes (p < 0.05) at 24 h post-transfection and 351 genes differentially expressed (p < 0.05) at 72 h post-transfection (Table S3). In ReNcell CX cells, MSNP1AS overexpression revealed 267 genes differentially expressed at 24 h post-transfection and 164 genes differentially expressed at 72 h post-transfection (Table S3). No single gene was significantly (p < 0.05) altered in each of the four experimental conditions (Table S3).

MSNP1AS overexpression did not alter expression of MSN, the transcript that encodes moesin protein and is bound by the MSNP1AS lncRNA. In SK-N-SH cells, MSN transcript was slightly increased at 24 h post-transfection (1.17-fold; p = 3.0 × 10−2) and at 72 h post-transfection (1.16-fold; p = 3.0 × 10−1). In ReNcell CX cells, a significant change in MSN transcript expression was not observed at 24 h post-transfection (0.97-fold; p = 8.0 × 10−1) and at 72 h post-transfection (0.92-fold; p = 5.0 × 10−1). These results suggest that, although MSNP1AS regulates expression of moesin protein [9], MSNP1AS does not directly regulate the expression of the MSN transcript.

3.3. Transcriptional Consequences of MSNP1AS Overexpression Are Enriched in Protein Synthesis and Chromatin Regulation

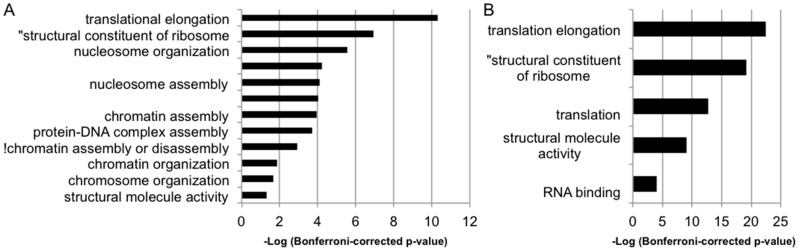

Gene ontology (GO) analysis using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) web server for differentially expressed (p < 0.05) genes revealed an enrichment of genes involved in protein synthesis and chromatin regulation (Figure 3A; Table S4). In SK-N-SH cells at 72 h post-transfection of the MSNP1AS overexpression construct, the 351 genes with altered expression (p < 0.05) were enriched for genes involved in translational elongation (Bonferroni corrected p = 4.7 × 10−11), structural constituent of ribosome (Bonferroni corrected p = 1.2 × 10−7), and nucleosome organization (Bonferroni corrected p = 2.8 × 10−6). No enrichment that survived Bonferroni correction was observed among the 157 differentially expressed genes in SK-N-SH cells at 24 h post-transfection. However, a trend toward enrichment of chromatin related genes was observed in SK-N-SH cells at 24 h (uncorrected p = 5.8 × 10−2) with some of the same genes differentially expressed as SK-N-SH at 72 h post-transfection (e.g., HIST1H2AJ, Table S4).

Figure 3.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis on all differentially expressed genes due to overexpression of MSNP1AS. GO enrichment analysis was performed on (A) SK-N-SH cells after 72 h, and (B) ReNcell CX cells after 24 h.

Similarly, in ReNcell CX human neural progenitor cells at 24 h post-transfection, differentially expressed (p < 0.05) genes were enriched for translational elongation (Bonferroni corrected p = 3.3 × 10−23), structural constituent of ribosome (Bonferroni corrected p = 7.3 × 10−20), and translation (Bonferroni corrected p = 1.7 × 10−13) (Figure 3B; Table S4). No enrichment that survived Bonferroni correction was observed among the 164 genes differentially expressed in ReNcell CX cells at 72 h post-transfection. However, an enrichment of genes involved in translation (uncorrected p = 4.0 × 10−2) was among the top results in ReNcell CX cells at 72 h post-transfection. These data suggest that genes involved in translation are altered by MSNP1AS overexpression.

4. Discussion

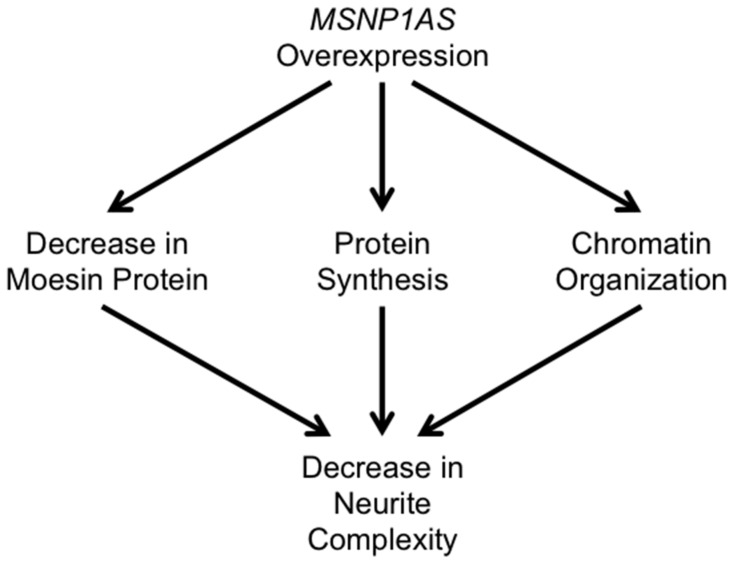

The data presented here indicate that overexpression of the ASD-associated lncRNA MSNP1AS alters neuronal architecture in human neural progenitor cells by three potential mechanisms (Figure 4). As we previously described [9], MSNP1AS overexpression decreases expression of moesin protein, which is known to decrease neuronal complexity [12]. Here, we demonstrate that MSNP1AS overexpression also changes the expression of genes involved in protein synthesis and chromatin organization. Therefore, MSNP1AS overexpression has multiple molecular functions: MSNP1AS alters expression of genes that contribute to chromatin organization; MSNP1AS binds MSN and alters the translation of moesin protein; and MSNP1AS alters the expression of genes that regulate translation more globally (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Potential mechanisms by which MSNP1AS alters neuronal architecture. MSNP1AS overexpression decreases the expression of moesin protein, as well as the expression of genes involved in protein synthesis and chromatin organization, leading to a decrease in neurite complexity.

MSNP1AS was discovered as the functional element revealed by an ASD genome-wide association study [9]. The allele frequencies of the chromosome 5p14.1 genetic variants with genome-wide significant association are high: greater than half the population carries at least one copy of the risk allele [7]. It is unclear whether individuals who are homozygous for the rs4307059 risk allele are at higher risk for ASD than those heterozygous at rs4307059. However, the expression of MSNP1AS is increased in the postmortem temporal cortex of individuals who are homozygous for rs4307059 compared to individuals who are heterozygous for rs4307059 [9]. It is striking that the biological functions of this ASD-associated lncRNA—protein synthesis and chromatin organization—are matched closely to the biological functions revealed by genes with rare de novo mutations associated with ASD [26,27]. These results suggest that both common and rare ASD-associated variants converge upon the common molecular pathways. Further, the chromosome 5p14.1 genetic marker with the most significant association (rs4307059 with ASD association p = 10−10) also contributes to altered social communication in a general population sample [8]. Together, these data suggest common molecular pathways that contribute to social communication that involve protein translation and chromatin organization.

MSNP1AS is antisense to moesin (membrane-organizing extension spike protein). Moesin is a member of the ERM (exrin/radixin/moesin) family of proteins that link the actin filaments to the cellular membrane. Along with radixin, moesin protein localizes to growth cones and filopodia that emanate from neurite shafts, both regions of high motility and growth. These proteins are especially important during development, as shown in rat cerebral cortex. In rats, ERM protein expression reaches a maximum near birth and gradually declines through postnatal development [12], which is during synaptic maturation. In the intermediate zone of developing rat cerebral cortex, ERM proteins are significantly expressed in neurite extensions at embryonic day 17 [11], a time of substantial synapse formation. They regulate adhesion receptors, signaling molecules that provide spatial information to the cell, and growth cone actin to mediate attractive growth cone guidance [28]. When antisense RNA is used to knockdown moesin in cultured hippocampal and cortical neurons, specific phenotypes are observed, including a dramatic reduction in the rate of neurite advancement [12], suppression of neurite formation [10], growth cone collapse [12], suppression of an increase in dendritic spine formation induced by estrogen [14], and suppression of an increase in active presynaptic boutons induced by glutamate [13]. In addition, ERM proteins have been shown to mediate neuritogenesis [29]. These data denote that the function of moesin involves both regulating axonal growth cone development presynaptically and initiating dendritic spine development postsynaptically. Moesin knockout mice have not been evaluated for behavioral phenotypes or brain development.

While MSN transcripts did not undergo a significant change in gene expression, significant alterations are observed in neurite development. As we previously described, overexpressed MSNP1AS binds MSN transcript and prevents translation of moesin protein. The current study expands our knowledge of MSNP1AS overexpression in two ways. First, the observation that MSNP1AS overexpression does not alter expression of MSN transcript indicates that MSNP1AS does not directly contribute to the regulation of the MSN transcription. Instead, in relation to the regulation of moesin, it appears that MSNP1AS acts only to inhibit the translation of moesin protein. Second, MSNP1AS acts more globally than just inhibiting the translation of moesin. The overexpression of MSNP1AS caused changes in the expression of genes involved in the protein synthesis and chromatin regulation. These transcriptional changes suggest that MSNP1AS participates in global biological processes that impact neuronal differentiation beyond its impact on moesin. Additional experiments will be necessary to determine the relative contributions of MSNP1AS to the biological processes of chromatin regulation, protein synthesis, and the regulation of moesin. It will be important to determine the expression of moesin protein and the MSNP1AS noncoding RNA in neurons derived from patients with the ASD-associated rs4307059 allele, as well as from patients with Cri-du-chat syndrome with deletion of chromosome 5p14.1, as these experiments may provide further evidence of a contribution of MSNP1AS to altered brain development. It will also be important to determine if individuals with ASD and the ASD-associated rs4307059 allele exhibit common comorbid features of ASD, such as gastrointestinal disorders or epilepsy. A network analysis of microarray data from postmortem ASD brain placed MSN as a central node [30]. However, there was no enrichment of the genes in the MSN node and the genes with altered expression following MSNP1AS over-expression identified here.

In this study, overexpressed MSNP1AS results in shortened neurites and fewer neurites per cell, indicating that neuritogenesis and extension are both impacted. The decreased neurite number and growth upon overexpression of MSNP1AS reinforces studies that suggest that altered short- and long-range connectivity in the brains of autism patients may be contributing to the pathogenesis of the disorder [31]. This is in line with global observations of decreased connectivity in the brains of individuals with ASD [16,17,18,19,20,32], although there is evidence for increased connectivity between some brain regions in ASD [19,20].

Noncoding RNA comprise 90% of the human genome and are believed to contribute to regulatory function as enhancers and promoters [33,34]. These elements differentiate across space and time in a significant way, but the exact functional roles of most lncRNAs have not been quantified [35,36,37]. The contributions of lncRNAs to psychiatric disorders are a topic of ongoing research [38]. The data from this study provide further evidence for pathways reported to influence ASD, as well as giving additional insight into the molecular function of the ASD-associated lncRNA, MSNP1AS.

5. Conclusions

We previously identified the lncRNA MSNP1AS as a functional element revealed by genome wide significant association with ASD. Using a candidate gene approach, we showed that one function of MSNP1AS is to regulate the expression of moesin protein. The data presented here indicate that MSNP1AS over-expression does not significantly alter the expression of the MSN transcript, suggesting that MSNP1AS functions specifically at regulating the translation of the MSN transcript to moesin protein. Further, the unbiased RNA sequencing data revealed that over-expression of MSNP1AS alters the expression of genes involved in protein synthesis and chromatin organization. These biological processes are also implicated by rare mutations associated with ASD, suggesting convergent molecular mechanisms that contribute to the altered brain development of ASD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH100172 (to Daniel B. Campbell) and R21MH099504 (to Daniel B. Campbell).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/7/10/76/s1, Table S1: RNA sequencing metrics, Table S2: quantitative over-expression of MSNP1AS, Table S3: genes differentially expressed following MSNP1AS over-expression, Table S4: gene networks differentially expressed following MSNP1AS over-expression.

Author Contributions

Jessica J. DeWitt and Daniel B. Campbell conceived and designed the experiments; Jessica J. DeWitt, Nicole Grepo, and Brent Wilkinson performed the experiments; Jessica J. DeWitt analyzed the data; Oleg V. Evgrafov and James A. Knowles contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; Jessica J. DeWitt and Daniel B. Campbell wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Levitt P., Campbell D.B. The genetic and neurobiologic compass points toward common signaling dysfunctions in autism spectrum disorders. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:747–754. doi: 10.1172/JCI37934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeWitt J., Campbell D.B. Targeting noncoding RNA for treatment of autism spectrum disorders. In: Hu V., editor. Frontiers in Autism Research, Diagnosis, and Treatment. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.; Singapore: 2014. pp. 203–228. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahin M., Sur M. Genes, circuits, and precision therapies for autism and related neurodevelopmental disorders. Science. 2015 doi: 10.1126/science.aab3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geschwind D.H., State M.W. Gene hunting in autism spectrum disorder: On the path to precision medicine. Lancet. Neurol. 2015;14:1109–1120. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00044-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klei L., Sanders S.J., Murtha M.T., Hus V., Lowe J.K., Willsey A.J., Moreno-De-Luca D., Yu T.W., Fombonne E., Geschwind D., et al. Common genetic variants, acting additively, are a major source of risk for autism. Mol. Autism. 2012 doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J.A., Penagarikano O., Belgard T.G., Swarup V., Geschwind D.H. The emerging picture of autism spectrum disorder: Genetics and pathology. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2015;10:111–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012414-040405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang K., Zhang H., Ma D., Bucan M., Glessner J.T., Abrahams B.S., Salyakina D., Imielinski M., Bradfield J.P., Sleiman P.M., et al. Common genetic variants on 5p14.1 associate with autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2009;459:528–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.St Pourcain B., Wang K., Glessner J.T., Golding J., Steer C., Ring S.M., Skuse D.H., Grant S.F., Hakonarson H., Davey Smith G. Association between a high-risk autism locus on 5p14 and social communication spectrum phenotypes in the general population. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2010;167:1364–1372. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerin T., Ramanathan A., Rivas K., Grepo N., Coetzee G.A., Campbell D.B. A noncoding RNA antisense to moesin at 5p14.1 in autism. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furutani Y., Matsuno H., Kawasaki M., Sasaki T., Mori K., Yoshihara Y. Interaction between telencephalin and ERM family proteins mediates dendritic filopodia formation. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:8866–8876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1047-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mintz C.D., Dickson T.C., Gripp M.L., Salton S.R., Benson D.L. Erms colocalize transiently with L1 during neocortical axon outgrowth. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;464:438–448. doi: 10.1002/cne.10809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paglini G., Kunda P., Quiroga S., Kosik K., Caceres A. Suppression of radixin and moesin alters growth cone morphology, motility, and process formation in primary cultured neurons. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:443–455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim H.S., Bae C.D., Park J. Glutamate receptor-mediated phosphorylation of ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins is implicated in filopodial protrusion of primary cultured hippocampal neuronal cells. J. Neurochem. 2010;113:1565–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez A.M., Flamini M.I., Fu X.D., Mannella P., Giretti M.S., Goglia L., Genazzani A.R., Simoncini T. Rapid signaling of estrogen to WAVE1 and moesin controls neuronal spine formation via the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009;23:1193–1202. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Courchesne E., Pierce K. Why the frontal cortex in autism might be talking only to itself: Local over-connectivity but long-distance disconnection. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005;15:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardan A.Y., Pabalan M., Gupta N., Bansal R., Melhem N.M., Fedorov S., Keshavan M.S., Minshew N.J. Corpus callosum volume in children with autism. Psychiatry Res. 2009;174:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frazier T.W., Hardan A.Y. A meta-analysis of the corpus callosum in autism. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;66:935–941. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brito A.R., Vasconcelos M.M., Domingues R.C., Hygino da Cruz L.C., Jr., Rodrigues Lde S., Gasparetto E.L., Calcada C.A. Diffusion tensor imaging findings in school-aged autistic children. J. Neuroimaging. 2009;19:337–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2009.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monk C.S., Peltier S.J., Wiggins J.L., Weng S.J., Carrasco M., Risi S., Lord C. Abnormalities of intrinsic functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroimage. 2009;47:764–772. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minshew N.J., Keller T.A. The nature of brain dysfunction in autism: Functional brain imaging studies. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2010;23:124–130. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833782d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trapnell C., Pachter L., Salzberg S.L. Tophat: Discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R., Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The sequence alignment/map format and samtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trapnell C., Williams B.A., Pertea G., Mortazavi A., Kwan G., van Baren M.J., Salzberg S.L., Wold B.J., Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang D.W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using david bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang D.W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huguet G., Ey E., Bourgeron T. The genetic landscapes of autism spectrum disorders. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2013;14:191–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Rubeis S., He X., Goldberg A.P., Poultney C.S., Samocha K., Cicek A.E., Kou Y., Liu L., Fromer M., Walker S., et al. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature. 2014;515:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nature13772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsick B.M., San Miguel-Ruiz J.E., Letourneau P.C. Activation of ezrin/radixin/moesin mediates attractive growth cone guidance through regulation of growth cone actin and adhesion receptors. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:282–296. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4794-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsumoto Y., Inden M., Tamura A., Hatano R., Tsukita S., Asano S. Ezrin mediates neuritogenesis via down-regulation of RhoA activity in cultured cortical neurons. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voineagu I., Wang X., Johnston P., Lowe J.K., Tian Y., Horvath S., Mill J., Cantor R.M., Blencowe B.J., Geschwind D.H. Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology. Nature. 2011;474:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belmonte M.K., Allen G., Beckel-Mitchener A., Boulanger L.M., Carper R.A., Webb S.J. Autism and abnormal development of brain connectivity. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:9228–9231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3340-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carper R.A., Courchesne E. Localized enlargement of the frontal cortex in early autism. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lander E.S., Linton L.M., Birren B., Nusbaum C., Zody M.C., Baldwin J., Devon K., Dewar K., Doyle M., FitzHugh W., et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venter J.C., Adams M.D., Myers E.W., Li P.W., Mural R.J., Sutton G.G., Smith H.O., Yandell M., Evans C.A., Holt R.A., et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine M., Davidson E.H. Gene regulatory networks for development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4936–4942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408031102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee T.I., Young R.A. Transcriptional regulation and its misregulation in disease. Cell. 2013;152:1237–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visel A., Rubin E.M., Pennacchio L.A. Genomic views of distant-acting enhancers. Nature. 2009;461:199–205. doi: 10.1038/nature08451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akbarian S., Liu C., Knowles J.A., Vaccarino F.M., Farnham P.J., Crawford G.E., Jaffe A.E., Pinto D., Dracheva S., Geschwind D.H., et al. The psychencode project. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:1707–1712. doi: 10.1038/nn.4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.