Abstract

Indigestible resistant starches (RS) are substrates for gut-microbial metabolism and have been shown to attenuate intestinal inflammation but the supporting evidence is inconsistent and lacks mechanistic explanation. We have recently reported dietary RS type 4 (RS4) induced improvements in immunometabolic functions in humans and a concomitant increase in butyrogenic gut-bacteria. Since inflammation is a key component in metabolic diseases, here we investigated the effects of RS4-derived butyrate on epigenetic repression of pro-inflammatory genes in vivo and in vitro. RS4-fed mice, compared to the control-diet group, had higher cecal butyrate and increased tri-methylation of lysine 27 on histone 3 (H3K27me3) in the promoter of nuclear factor-kappa-B1 (NFκB1) in the colon tissue. The H3K27me3-enrichment inversely correlated with concentration dependent down-regulation of NFκB1 in sodium butyrate treated human colon epithelial cells. Two additional inflammatory genes were attenuated by sodium butyrate, but were not linked with H3K27me3 changes. This exploratory study presents a new opportunity for studying underlying H3K27me3 and other methylation modifying mechanisms linked to RS4 biological activity.

Keywords: resistant starch type 4, sodium butyrate, H3K27me3, short chain fatty acid, inflammation

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Gut microbiota utilizes prebiotic fibers like resistant starch (RS) as a substrate to produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that is proposed to play an anti-inflammatory role in the maintenance of intestinal immune homeostasis1, although conflicting results exist2. Consumption of a fiber-rich diet is nevertheless considered beneficial in several diseases such as obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, and metabolic syndrome (MetS), all of which are associated with gut microbial dysbiosis and dysregulated mucosal immunity3. In particular, inflammation is considered as a key pathophysiological player in MetS4. We previously reported that consuming RS type 4-(RS4)-enriched flour (30% v/v) as part of a routine communal diet has significant cholesterol-lowering effects in healthy as well as in subjects with signs of MetS5. A retrospective follow-up of the study showed that participants who consumed RS4 had increased fecal SCFAs, particularly butyrate, in conjunction with increased butyrogenic microbiota in fecal samples6. Butyrate is one of the three major forms of SCFAs and has both trophic and bioactive functions on host cells by correcting the altered ratio of the gut bacteria and protecting against the potential pro-inflammatory molecules7. It has been reported that increasing large-bowel butyrate supply has the potential to promote colonic integrity and lower the risk for colonic inflammation8. In that context this proof-of-concept study aimed to explore if RS4 (chemically modified RS), particularly through butyrate production, epigenetically regulates inflammatory gene expression in the gut.

Histone modifications, especially histone acetylation and methylation, play a dominant role in epigenomic regulation of gene expression9. Butyrate is well known as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor that alters chromatin structure through histone acetylation, which in turn affects target gene expression associated with the maintenance of gut immune homeostasis1, 10. Butyrate’s anti-inflammatory activities1 result from both HDAC dependent and independent inhibition of transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB)11, 12 as well as suppression of the downstream pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines13, 14. However, knowledge is limited regarding the role of butyrate in modulation of histone tail methylation. Of particular interest, in the context of inflammatory gene expression down-regulation, is the trimethylation of H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3), an important and well-studied modification which is frequently associated with transcriptional repression and gene silencing15, 16.

In the present study, the wheat-derived cross-linked RS4 is used which was reported to be effective in attenuation of postprandial glucose and insulin levels in humans17. Since RS4 is insoluble, we first examined the in vitro effects of sodium butyrate (NaBu) on H3K27me3 enrichment of gene promoters in conjunction with mRNA and protein expression of selected inflammatory markers in a human colonic epithelial cell line, followed by a validation of RS4-induced butyrate production and a concomitant H3K27me3 modifying effects in vivo in mouse colon tissue. Of the three selected inflammatory markers studied, was a transcriptional factor NFκB1, which belongs to the NFκB family of transcription factors18. The transcription factors of the NF-κB family control the expression of a large number of target genes in response to changes in the environment, thereby helping to orchestrate inflammatory and immune responses and an aberrant NF-κB activation underlies various disease states. The NF-κB transcription factor family in mammals consists of five proteins, p65 (RelA), RelB, c-Rel, p105/p50 (NF-κB1), and p100/52 (NF-κB2) that associate with each other to form distinct transcriptionally active homo- and heterodimeric complexes. Although, the specific physiological role of individual NF-κB dimers are not fully understood, they all share a conserved 300 amino acid long amino-terminal Rel homology domain, and sequences within the RHD are required for dimerization, DNA binding, interaction with IκBs, as well as nuclear translocation18. The remaining two inflammatory mediators represented a chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2)13, and a cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10)14.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) with 4 mM L-glutamine and 4.5 g/l glucose was purchased from HyClone (Logan, UT), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and trypLE were purchased from Invitrogen Gibco (Grand Island, NY). Dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO), lipo-polysaccharide (LPS, from Escherichia coli, O55:B5), penicillin/streptomycin, hydrogen chloride-1-butanol, and NaBu (sodium salt of butyrate) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), while IFNγ was purchased from R&D Systems (McKinley, NB). For western blot, antibody against β-actin was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), antibody against NFκB1 was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA), and Dylight 800 anti-rabbit secondary antibody was purchased from Li-Cor Biosciences (Lincoln, NE). Anti-trimethyl-Histone H3 Lys27 and rabbit IgG negative control antibodies used for chromatin immuno-precipitation (ChIP) assay were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Billerica, MA). Enzymes used for ChIP assay, Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) and Proteinase K were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA) and Pierce (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), respectively. All other ChIP assay chemicals, aprotinin, DL-1, 4-Dithiothreitol (DTT), Nonidet-P40 (NP-40) were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL), while protein-A sepharose and sucrose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). ChIP incubation buffer was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and DNA purifying slurry for ChIP-graded DNA purification was purchased from Diagenode (Denville, NJ). 2-Ethylbutyric acid (99%) and 1-butanol (99.9%) used as internal standard in gas chromatography- mass spectrometry (GC-MS) were purchased from Acros Organics (Mullica Hill, NJ) and Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA), respectively. Hexane (>97.0%) and sodium sulphate (granular, anhydrous, >99.0%) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH), while the inert helium gas was purchased from Matheson (Sioux Falls, SD). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by IDT DNA Inc. (Coralville, IA).

2.2. Cell culture and treatment

All in vitro assays were conducted in human colon cancer cell line, SW480 (CCL-228, ATCC, Manassas, VA). Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin (25 U/ml)/streptomycin (25 µg/ml) in a 95% air/5% CO2-humidified atmosphere at 37 °C. This cell line was cultured as previously described15. Briefly, SW480 cells were pre-treated with IFNγ (10 ng/ml) or control medium for 12 h, treated with NaBu or DMEM (as a negative control) for 5 h and then stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 h. For every experiment, one positive control (cells treated with LPS) and one negative control (cells treated without LPS or any NaBu treatments) were included. Two replicates were used for both the treatments and controls. LPS and NaBu were reconstituted in DMEM.

2.3. Total RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically by absorption measurements at 260 nm and 280 nm using the NanoDrop system (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). RNA was then treated with DNase I (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), following the manufacturer's guidelines to remove any traces of DNA contamination. The cDNAs were synthesized using 3 µg of RNA for each sample using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription (RT) Kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), following the manufacturers’ protocol. Two microliters of each diluted sample was added to 0.5 µl of gene-specific primers and 12.5 µl of Power SYBR green PCR master mix (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), and the final volume was brought to 25 µl by adding sterile distilled water. PCR amplifications were performed on a MX3005P system (Stratagene, San Diego, CA) using one cycle at 50 °C for 2 min, one cycle of 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C, and the last cycle with 95 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 30 s, and 95 °C for 30 s. RNA extraction, purification, cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR were performed as previously described19 in duplicate. Gene-specific primers used in the current study are described in Table 1. Calculations of relative gene expression levels were performed using the 2−ΔΔCt method20. The mRNA levels were normalized to a housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and expressed as a fold change relative to positive-control cells.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qRT PCR and ChIP assays

| Gene | qRT PCR (SW480 cells) | ChIP Assay (SW480 cells)/ (Mice tissue) |

|---|---|---|

| CCL2 | F: 5’-agtctctgccgcccttct-3’ R: 5’-gtgactggggcattgattg-3’ |

F: 5’-gtggtcagtctgggcttaatg-3’ R: 5’-ctgctgagaccaaatgagca-3’ |

| IL-10 | F: 5’-cataaattagaggtctccaaaatcg-3’ R: 5’-aaggggctgggtcagctat-3’ |

F: 5’-aaggccaatttaatccaaggtt-3’ R: 5’-tttggtttcctcaccctactgt-3’ |

| NFκB1 | F: 5’-accctgaccttgcctatttg-3’ R: 5’-agctctttttcccgatctcc-3’ |

F: 5’-ttggcaaaccccaaagag-3’/ F: 5’-cgatctgagtgtagccgaga-3’ R: 5’-ggtttcccacgatcgattt-3’/ R: 5’-gctgggcacaaaagtcaatc-3’ |

| GAPDH | F: 5’-agccacatcgctcagacac-3’ R: 5’-gcccaatacgaccaaatcc-3’ |

2.4. Western blot analysis

For immunoblot analyses, IFNγ-primed NaBu-treated human colon epithelial cells were activated with LPS for 4 h and harvested using RIPA lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 µg/ml leupeptin). The Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used to determine protein concentration. Proteins (35–50 µg/lane) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and the products were electrotransferred to polyvinyldene difluoride membranes (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 h, and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight (NFκB p105/p50). On the next day, membranes were incubated with Dylight 800 anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) for 1 h, and washed 3 times in PBS/T (0.1% Tween20 in PBS) all at room temperature. After rinsing in PBS/T, blots were imaged and quantitatively analyzed using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). A loading control protein, β-actin, was used to calculate the relative expression of NFκB p105 and p50 subunits.

2.5. Native ChIP assay in cell culture

ChIP assay was performed as we previously described15. Briefly, cells were lysed by suspending in a sequence of lytic and purification buffers. DNA fragments of 300–800 bp long were obtained by treating the nuclear pellet, obtained from lytic buffers, with MNase (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) in digestion buffer for 6 min. DNA fragments were immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies (anti-trimethyl-Histone H3 Lys27 and rabbit IgG) at 4 °C overnight. Immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were extracted using protein-A sepharose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and purified using DNA purifying slurry (Diagenode, Denville, NJ). The amount of purified DNA was estimated by nanodrop of 200 ng purified DNA template using SYBR green chemistry as described in RT-qPCR quantification section. Promoter-specific primers used in the current study are described in Table 1. Calculations are expressed as a percentage of the input DNA.

2.6. Animal housing, diet and tissue collection

All in vivo procedures were approved and conducted following the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of South Dakota State University guidelines. Six-week old male KK.Cg-Ay/a (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) mice were grouped at random to consume either RS4 or control diets. To avoid confounding effects of sex on weight gain, which was a measurable outcome for the study, only male mice were considered. Also, this study was conducted prior to the implementation of federal policy for considering both male and female sexes in biomedical experiments (NOT-OD-15-102). Mice were caged in groups of three in a laboratory animal facility at an ambient temperature of 24–26 °C with 12-h light/dark cycle. During the first 3 weeks mice were allowed to acclimatize while consuming standard rodent chow, LabDiet® 5001 (LabDiet, St. Louis, MO). Animals were then switched to experimental diets (LabDiet, St. Louis, MO) formulated based on AIN 9321 either with 20% RS4 or control diet (CD). Detailed composition of experimental diets is provided in Table 2. Mice were provided the experimental diets and water ad libitum for 12 weeks. Following CO2 euthanasia, colon tissues and cecum samples were immediately collected, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Table 2.

Composition of experimental diets per 100 grams

| Ingredients | Control Diet | RS4 Diet |

|---|---|---|

| Midsol™ 501 | 31.77 | 27.07 |

| Fibersym RW2 | 0.00 | 23.5 |

| Powdered cellulose | 18.80 | 0.00 |

| Casein – vitamin free | 14.00 | 14.00 |

| Dextrin | 13.67 | 13.67 |

| Sucrose | 8.82 | 8.82 |

| Soybean oil | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| AIN 93M mineral mix | 3.50 | 3.50 |

| AIN 93M vitamin mix | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Choline Bitartrate | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| L-Cystine | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| t-Butylhyrdoquinone | 0.0008 | 0.0008 |

Midsol™ 50 is wheat starch with the energy content of 359.5 kcal/100 g.

Fibersym RW is resistant starch type 4 (85%, dry basis) with the energy content of 56.5 kcal/100 g. Midsol™ 50 and Fibersym RW were obtained from MGP Ingredients Inc. (Atchison, KS) and incorporated in the mouse diet by LabDiet (St Louis, MO).

2.7. Determination of cecal weight and butyrate analyses

Cecal tissues were weighed and pooled together (>500 mg in total weight) to represent one sample and vortexed for 1 min with 1 ml of internal standard (2-ethylbutyric acid in 1-butanol, 0.25 mg/ml). 0.5 ml of hexane (organic solvent) and 2 ml of HCl-1-butanol (derivatizing agent) were then added to each sample followed by an additional 1 min vortexing and 5 min sonication prior to being purged with an inert helium gas. The tubes were immediately closed and each sealed container was incubated in water bath at 60 °C overnight in order to catalyze the derivatization of butyrate analyte. Upon being cooled to room temperature, 1.5 ml of additional hexane and 15 ml of deionized water were added. Samples were mixed by vortexing 1 min following each addition and then centrifuged at 3000 g for 2 min. The top organic layer (~2 ml) was transferred into a 5 ml graduated vial before blowing down with helium to one-fourth of the volume, thereby increasing the final concentration of internal standard from 0.25 mg/ml to 1 mg/ml. Finally, each sample was transferred into a sampling vial containing a 150 µl insert and ~10 mg of anhydrous sodium sulphate was added to remove the water content before running into the GC-MS.

SCFAs were derivatized to obtain the corresponding butyl-esters (SCFABE) prior to their gas chromatography (Agilent 7890A, Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and mass spectrometry (5977A MSD, Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) using HP-5MS UI capillary column (30 m × 0.25mm, 0.2 µm thickness, Agilent, Wilmington, DE, USA). Using hydrogen as carrier gas at a constant flow of 1.9 mL/min, a typical injection volume (1 µl) was injected in the split mode (1:10). The separation of SCFABE was achieved using an oven temperature program as follow: initial elution temperature of 55 °C for 4 min, an increase by 5 °C/min to 120 °C followed by 20 °C/min to 220 °C for 10 min. The selective mass detector was operated in the ‘single ion monitoring and scan’ (SIM/Scan) mode with the source temperature (150 °C) and the electron energy (70 eV). The abundance of butyrate analyte was identified by acquiring ions of a specific m/z value. Finally, the data were analyzed and expressed as a unit of mg/g of cecal tissues used.

2.8. Native ChIP assay in mouse colon tissues

Colon tissues were collected from mice immediately after sacrifice, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. On the day of assay, around 0.2 g of colon tissues were rinsed in cold PBS and homogenized on ice in a pre-chilled tube with 1 ml of ice-cold Buffer 1 (0.06 M KCL, 15 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 15 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4–7.6, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.3 M sucrose, 180 µg aprotinin, 5 mM sodium butyrate, 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM DTT), until the homogenate was free of clumps. The homogenate was then filtered through four layers of muslin cheesecloth, pre-autoclaved and pre-moistened with Buffer 1. The filtered cells were treated in the same way as described in the Native ChIP assay in cell culture section. Promoter methylation of genes of interest was determined in mice fed RS4 or CD. Promoter-specific primers used in the current study are described in Table 1.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the significance between groups followed by the post-ANOVA Dunnett test. Intergroup comparisons in Western blot, ChIP assay in mouse colon tissues and for SCFAs in mouse cecal tissues were determined using Student’s t-test. A bivariate analysis was carried out using correlation coefficient method and presented as Pearson’s r. The significance of each treatment was interpreted by comparison with the appropriate control, as described under specific methods. Experiments were repeated at least three times. A probability (p) value of 0.05 or less was considered to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. NaBu attenuates expression of inflammatory mediators in a concentration dependent manner in colon epithelial cells

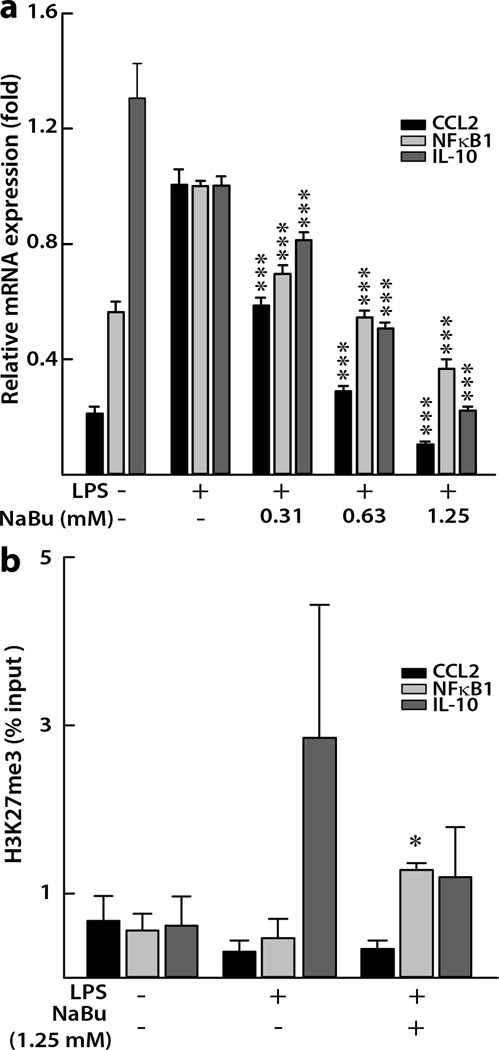

LPS stimulated the production of pro-inflammatory mediators in IFNγ-primed human colon epithelial cells. In the cells treated with NaBu, compared to the positive control cells treated with LPS alone, we observed a concentration-dependent mRNA attenuation of CCL2 and NFκB1 (Figure 1a). The highest concentration of NaBu tested (1.25 mM) showed the strongest attenuation, lowering the relative mRNA expression of CCL2 and NFκB1 by 90% and 63%, respectively (both p < 0.001). We also observed the similar effects in case of cytokine IL-10, where NaBu (1.25 mM) inhibited IL-10 mRNA by 78% (p < 0.001, Figure 1a). The untreated cells that served as negative control showed the highest level of IL-10, indicating the potential anti-inflammatory role of IL-10 in the absence of a strong immune challenge by LPS (Figure 1a). However, it is possible that IL-10 gained a pro-inflammatory characteristics when primed with IFNγ prior to LPS induction as was observed by Sharif et al22 and hence subsequently responded to NaBu in a similar manner to that of the other two pro-inflammatory mediators. This point is further elaborated in the “discussion” section.

Figure 1. Effects of NaBu on inflammatory gene expression in human colon epithelial cells.

(a) Concentration-dependent mRNA expression of inflammatory genes relative to a housekeeping gene, GAPDH. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6), ***p < 0.001 compared with LPS treated (10 ng/ml) positive control. (b) Histone 3 lysine 27 tri-methylation (H3K27me3) changes at promoter regions of inflammatory genes in cells treated with 1.25 mM NaBu for 5 h. Average percentage input ± SEM from each experiment (n ≥ 3) is plotted. *p < 0.05 compared with LPS treated positive control cells.

3.2. NaBu enriched H3K27me3 in the promoter of NFκB1 in colon epithelial cells

For ChIP assay we chose the highest dose (1.25 mM) of NaBu due to its most suppressive effects as observed for the gene expression data (Figure 1a). Compared with a positive control (Figure 1b), we observed the enrichment of H3K27me3 on the promoter region of NFκB1 (0.47 ± 0.23% vs 1.28 ± 0.08%, p < 0.05). The H3K27me3 enrichment pattern was not clear for the IL-10 promoter, possibly due to high inter-sample variation. For CCL2, a similar enrichment pattern to that of NFκB1 was absent, indicating the possibility of another gene regulatory mechanism influencing its mRNA downregulation (Figure 1). Since CCL2 is a downstream effector of NFκB signaling23, it is possible that the mRNA suppression of CCL2 is due to inhibition of NFκB1.

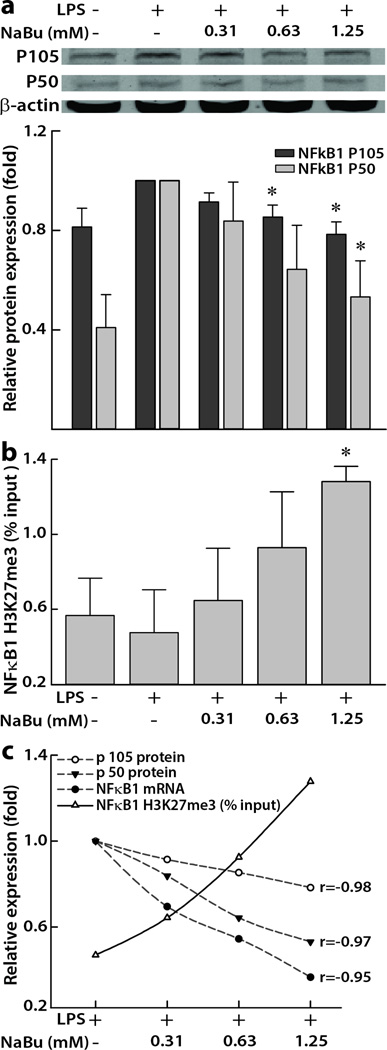

3.3. Concentration-dependent suppression of NFκB1 protein and mRNA by NaBu inversely correlated with concentration-dependent enrichment of H3K27me3 in the NFκB1 promoter

We further examined the concentration-dependent effects of NaBu on NFκB1 mRNA and protein downregulations simultaneously with the determination of a concentration-dependent H3K27me3 enrichment on NFκB1 promoter region. As shown in Figure 2a, the protein expression of p105 as well as the active p50 subunits of NFκB1 showed a concentration-dependent attenuation (p < 0.05) in response to NaBu in the IFNγ-primed and LPS-induced human intestinal epithelial cells. Interestingly, the relative protein expressions of both the sub units dropped close to the level of the negative control when treated with the 1.25 mM NaBu (p105: 0.77 ± 0.03 vs 0.81 ± 0.08 folds and p50: 0.53 ± 0.15 vs 0.41 ± 0.13 folds). The suppression of both the subunits also negatively correlated with a simultaneous concentration-dependent upregulation of H3K27me3 modifications on the promoter region of NFκB1 (Figures 2b and 2c) (p105: Pearson’s r = −0.98, p = 0.022 and p50: Pearson’s r = −0.97, p = 0.025). Further, NaBu-associated H3K27me3 enrichment of NFκB1 promoter also inversely correlated with the relative NFκB1 mRNA expressions (Pearson’s r = −0.95, p = 0.045, Figures 1a, 2b, and 2c).

Figure 2. Concentration-dependent effects of NaBu on NFκB1 in human colon epithelial cells.

(a) Representative immunoblots showing the suppression of total cellular NFκB1 subunits p105 and p50. Densitometric analyses showing relative protein expressions normalized to β-actin proteins and expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *p < 0.05, compared with LPS (10 ng/mL) treated positive control. (b) Histone 3 lysine 27 tri-methylation (H3K27me3) changes at promoter regions of NFκB1 in cells treated with different concentrations (0.31 to 1.25 mM) of NaBu for 5 h. Data points represent the input ± SEM (n ≥ 4). *p < 0.05, compared with LPS control.

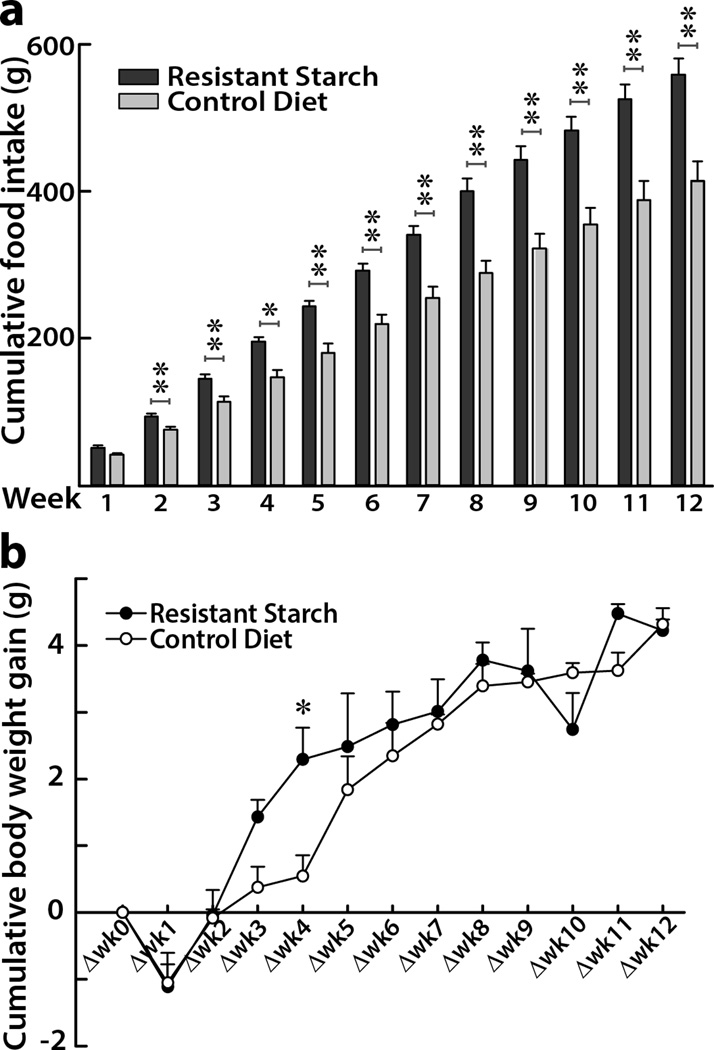

3.4. Body mass and food intake in mice study

We have previously reported that RS4-enriched diet may be effective for reducing pathophysiological consequences in humans with MetS5. Since KK.Cg-Ay/a mice develops hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, glucose intolerance and obesity by eight weeks of age, we in this study utilized KK.Cg-Ay/a mouse model to mimic age-related MetS in humans24, evaluating the effects of RS4 intake on butyrate production in the cecum and butyrate-associated epigenetic regulation of inflammatory genes in the colon tissue. Since RS4 is a stealth ingredient25, we incorporated RS4 in the mouse chow (20% v/v) and adjusted the CD to make it isocaloric with the addition of cellulose (Table 2). At the end of the 12-week feeding study, the cumulative food intake in RS4 group was around 35% higher when compared to that of CD group (560 ± 22 g vs 415 ± 26 g, p = 0.004, Figure 3a). However, the cumulative body weight increase in both groups were similar during the 12-week period (Figure 3b), suggesting a possible higher metabolic efficiency of RS4 diet than that of the control diet.

Figure 3. Effects of RS4 on feed intake and body weight in KK.Cg- Ay/a mice.

Cumulative food intake (a) and cumulative body weight gain (b) over a 12 week period in six-week old KK.Cg-Ay/a mice fed with 20% RS4 (resistant starch) or control diet. Data points represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

3.5. Cecal butyrate increased after RS4 intake in mice (butyrogenic effect of RS4)

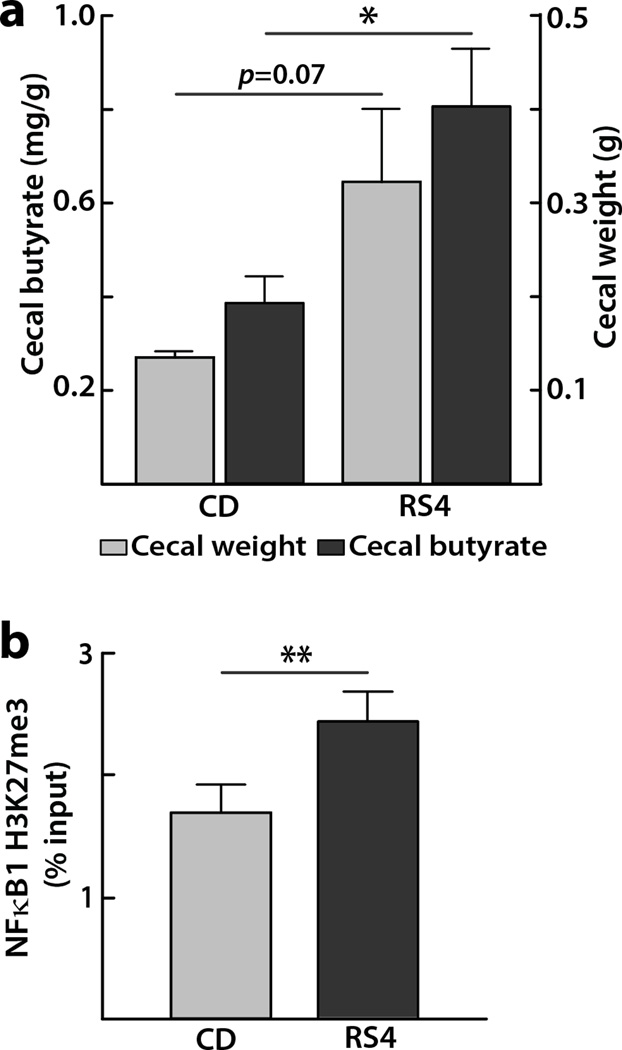

We have observed increased fecal butyrate levels post RS4 consumption in humans with MetS6, which was expected due to RS4 being a non-digestible fermentable fiber5. However fecal SCFAs represent <5% of the total SCFAs while the majority of SCFAs are efficiently absorbed in the intestinal lumen26. In contrast, the cecum butyrate concentrations from a MetS mouse model may represent a higher proportion of the SCFAs produced in the gut. The mice group receiving RS4 showed a trend for higher cecal weight compared to that of the CD group (322 ± 76 mg vs 135 ± 5 mg, p = 0.07, Figure 4a), which is in line with a previous report where fermentation of RS type 2 and RS type 3 increased the cecal weight in mice27. Using these cecal samples, GC-MS analyses showed that butyrate concentration was about two-fold higher (0.81 ± 0.12 mg/g vs 0.39 ± 0.05 mg/g, p = 0.036) in the RS4 group than the CD group (Figure 4a).

Figure 4. Effects of RS4 on mice cecal weight, butyric acid levels and histone modification.

(a) Butyrate concentration (primary Y-axis on the left) per gram of cecal tissue (secondary Y-axis on the right) taken from KK.Cg-Ay/a mice after 12 week of feeding RS4 (20%) or control diet. Data represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3), *p < 0.05. (b) Diet-induced differential tri-methylated histone 3 modifications on lysine 27 (H3K27me3) at promoter regions NFκB1 in the colon tissues of KK.Cg-Ay/a mice fed with either RS4 (resistant starch, 20%) or control diet for 12 weeks. Average percentage input ± SEM from each experiment (n = 3) is plotted, **p < 0.01.

3.6. Dietary RS4 intake enriched H3K27me3 in the promoter region of NFκB1 in mouse colon tissue

After observing NaBu-mediated inhibition of histone modifications in vitro, we sought to examine the similar effects in the colon tissue from KK.Cg-Ay/a mice fed with 20% RS4 for 12 weeks. ChIP assay revealed enrichment of H3K27me3 modification on the promoter region of NFκB1 (1.4 fold, p = 0.01) after RS4 intervention compared with CD (Figure 4b). This result supports the concept that feeding a butyrogenic dietary fermentable fiber, such as RS4, enriches the epigenetic repressive mark (H3K27me3), potentially contributing to the amelioration of the gut inflammation, a key factor underlying many chronic disorders including MetS.

4. Discussion

Supplementation of diets with prebiotic fibers for potential mitigation of pro-inflammatory state in the context of chronic diseases, is an attractive area in public health research3. It was particularly proposed that the inhibition of inflammatory mediators through dietary enhancement of intestinal butyrate production has tremendous implications in the context of managing obesity-related metabolic diseases28. To our knowledge, this is the first report that dietary RS4 induced promoter-specific changes in the H3K27me3 enrichment in vivo likely by the way of increased colonic butyrate production. The in vitro observations further confirmed a concentration dependent repression of both NFκB1 mRNA and protein levels in response to NaBu with a concomitant enrichment in H3K27me3 levels.

Dietary fibers, which are otherwise indigestible to humans, undergo microbial fermentation in the hind-gut, particularly in the colon29. The colon is considered a metabolic organ where the mucosal epithelia absorb topical nutrients, such as SCFAs which play an important role in modulating gut immune system30. The gut microbiota is an essential component in the colonic microenvironment and an altered gut microbial composition or dysbiosis plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of intestinal as well as extra-intestinal diseases31. Butyrate acts as an energy source to epithelial cells7 and inhibits genetic mutation8 and oncogenic microRNA expression32 in rectal biopsies. In addition, the role of SCFAs in regulating colonic regulatory T cells (cTReg cells) in mice had been proposed33, 34. Butyrate increases the expression of FOXP3, a transcription factor connected to colon inflammation, by increasing activity of hisone acetylation in its promoter and enhancer region leading to downregulation of proinflammatory mediators33, 35, 36. As we6 and others37 have observed that RS4 mediates the modulation of butyrogenic gut microbiota, we hypothesized that the observed immunomodulatory effects of RS4 in humans are at least partially derived from the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of butyrate that is produced after microbial fermentation of the dietary RS4. To minimize use of animals, we first examined our hypothesis in an in vitro setting using a human intestinal colonic cell line but since RS4 is an insoluble fibre38, 39, we used sodium butyrate for the in vitro tests.

The cytokine IL-10 is predominantly anti-inflammatory in nature that suppresses the dendritic and macrophage cell functions40. The IL-10 may, however, acquire pro-inflammatory properties in inflammatory settings like endotoxemia, autoimmune diseases, and graft transplantations41–43. The balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory activities of IL-10 is regulated by type I IFN22. Priming with type I IFNs (IFNα or IFNβ) also leads to enhanced cellular responsiveness to IFNγ44, the latter acting as an enhancer of cellular responsiveness to LPS through the toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway in human intestinal epithelial cells, including SW48045. Therefore, in our study, it is possible that IL-10 showed a pro-inflammatory nature as the human colon epithelial cells were primed with IFNγ (10 ng/ mL) and stimulated with the LPS (10 ng/ ml), following Suzuki et al.45. Our results are also in line with the report of Saemann et al. that showed NaBu exerts its IL-10 enhancing properties only under the dose of 0.25 mM, while inhibits IL-10 above the concentration of 0.25 mM46. This finding further supports our observation of IL-10 inhibition by NaBu at the concentration range of 0.31 to 1.25 mM. Also of interest is that the normal physiologic level of SCFAs in portal blood is (0.38 ± 0.07 mM)47, signifying the concentrations used in our study are likely within the physiologically relevant range.

Although congenic, age-matched, and randomized mice were supplied with isocaloric control diet, the cumulative food intake was consistently higher in the RS4 group. It is possible that palatability of RS4 and cellulose were different with RS4, imparting minimal alteration of the physicochemical and organoleptic properties of the final food products39, the mouse chow in this case. Interestingly, in spite of higher food intake, but with expected similar basal metabolic rate and physical activity, the mice in the RS4 group did not have a significantly higher weight gain by the end of twelvth week. This is consistent with the previous findings by Gao et al.,48 where butyrate supplemented mice consumed higher feed intake and showed higher lean mass but lower fat mass, thus preventing diet-induced insulin resistance and obesity through more energy expenditure. In addition, the dietary fibers may also slow down the digestibility of protein and fats in diets, thereby decreasing the metabolizable energy content49. Since we also previously reported that RS4 consumption improves body composition of humans5, the current study further corroborates the previous findings in KK.Cg-Ay/a mice and supports the suitability of this mouse model for age-related MetS in humans as proposed by Kennedy et al24. The novelty of this research lies in the investigation of epigenetic mechanisms of butyrate on H3K27me3-enrichment that inversely correlated with concentration dependent down-regulation of a transcription factor NFκB1, which elegantly substantiates our previous findings of human health promoting5 and butyrogenic effects of RS46. Hence, RS4 and its derivative, butyrate, possesses promising clinical implications in the management of cardio-metabolic diseases in humans.

5. Conclusions

This exploratory study introduces a proof-of-concept that RS4 and its bacterial fermentation metabolite, butyrate, may function as an H3K27me3 modulator in conjunction with its suppressive effects on NFκB1 transcription factor in the colonic cells in the context of metabolic syndrome. Further characterization of prebiotic functional fibers-associated epigenetic alterations may provide effective strategies to mitigate the low-grade inflammation in the context of intestinal as well as extra-intestinal diseases associated with dysbiosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MGP Ingredients Inc., Atchison KS [3P2662], the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture [Hatch 1004817], and National Institutes of Health [R00AT4245] to M.D.

List of Abbreviations

- CCL2

C-C motif ligand 2

- CF

Control flour

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- H3K427me3

Tri-methylation of lysine 27 on histone 3

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- IL-10

Interleukin 10

- INFγ

Interferon gamma

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MetS

Metabolic syndrome

- NaBu

Sodium butyrate

- NFκB1

Nuclear factor-kappa-B1

- RS4

Resistant starch type IV

- SCFA

Short chain fatty acids

- TC

Total cholesterol

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Disclaimer

The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analyses, or toward any decision related to this manuscript. The opinions expressed in this presentation do not necessarily represent any official policies of the US Food and Drug Administration, or of its parent organization, the Department of Health and Human Services, and should not be considered as changes in regulatory procedures. Any mention of specific companies or products should not be regarded as endorsements.

Author contributions

Study conception, design and supervision: MD; Experimental work: YL, BU, ARFK, RJ; Provision of reagents/materials/equipment/analysis tools: MD, ARFK; Data analyses: YL, BU; Manuscript preparation: BU, MD, YL; All authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Meijer K, de Vos P, Priebe MG. Butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids as modulators of immunity: what relevance for health? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:715–721. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833eebe5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ordiz MI, May TD, Mihindukulasuriya K, Martin J, Crowley J, Tarr PI, Ryan K, Mortimer E, Gopalsamy G, Maleta K, Mitreva M, Young G, Manary MJ. The effect of dietary resistant starch type 2 on the microbiota and markers of gut inflammation in rural Malawi children. Microbiome. 2015;3:37. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown K, DeCoffe D, Molcan E, Gibson DL. Diet-induced dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and the effects on immunity and disease. Nutrients. 2012;4:1095–1119. doi: 10.3390/nu4081095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montecucco F, Mach F, Pende A. Inflammation is a key pathophysiological feature of metabolic syndrome. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:135984. doi: 10.1155/2013/135984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichenametla SN, Weidauer LA, Wey HE, Beare TM, Specker BL, Dey M. Resistant starch type 4-enriched diet lowered blood cholesterols and improved body composition in a double blind controlled cross-over intervention. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58:1365–1369. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upadhyaya B, McCormarck L, Fardin-Kia AR, Juenemann R, Nichenametla SN, Clapper J, Specker BL, Dey M. Impact of dietary resistant starch type 4 on human gut microbiota and immunometabolic functions. Scientific Reports. 2016 doi: 10.1038/srep28797. Under Minor Revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donohoe DR, Garge N, Zhang X, Sun W, O'Connell TM, Bunger MK, Bultman SJ. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon. Cell Metab. 2011;13:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Leu RK, Winter JM, Christophersen CT, Young GP, Humphreys KJ, Hu Y, Gratz SW, Miller RB, Topping DL, Bird AR, Conlon MA. Butyrylated starch intake can prevent red meat-induced O6-methyl-2-deoxyguanosine adducts in human rectal tissue: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Nutr. 2015;114:220–230. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515001750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li CJ, Li RW, Baldwin RLt, Blomberg le A, Wu S, Li W. Transcriptomic Sequencing Reveals a Set of Unique Genes Activated by Butyrate-Induced Histone Modification. Gene Regul Syst Bio. 2016;10:1–8. doi: 10.4137/GRSB.S35607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boffa LC, Vidali G, Mann RS, Allfrey VG. Suppression of histone deacetylation in vivo and in vitro by sodium butyrate. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:3364–3366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Place RF, Noonan EJ, Giardina C. HDAC inhibition prevents NF-kappa B activation by suppressing proteasome activity: down-regulation of proteasome subunit expression stabilizes I kappa B alpha. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segain JP, Raingeard de la Bletiere D, Bourreille A, Leray V, Gervois N, Rosales C, Ferrier L, Bonnet C, Blottiere HM, Galmiche JP. Butyrate inhibits inflammatory responses through NFkappaB inhibition: implications for Crohn's disease. Gut. 2000;47:397–403. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fusunyan RD, Quinn JJ, Fujimoto M, MacDermott RP, Sanderson IR. Butyrate switches the pattern of chemokine secretion by intestinal epithelial cells through histone acetylation. Mol Med. 1999;5:631–640. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Carli M, D'Elios MM, Zancuoghi G, Romagnani S, Del Prete G. Human Th1 and Th2 cells: functional properties, regulation of development and role in autoimmunity. Autoimmunity. 1994;18:301–308. doi: 10.3109/08916939409009532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Chakravarty S, Dey M. Phenethylisothiocyanate alters site- and promoter-specific histone tail modifications in cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rintisch C, Heinig M, Bauerfeind A, Schafer S, Mieth C, Patone G, Hummel O, Chen W, Cook S, Cuppen E, Colome-Tatche M, Johannes F, Jansen RC, Neil H, Werner M, Pravenec M, Vingron M, Hubner N. Natural variation of histone modification and its impact on gene expression in the rat genome. Genome Res. 2014;24:942–953. doi: 10.1101/gr.169029.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Tamimi EK, Seib PA, Snyder BS, Haub MD. Consumption of Cross-Linked Resistant Starch (RS4(XL)) on Glucose and Insulin Responses in Humans. J Nutr Metab. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/651063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oeckinghaus A, Ghosh S. The NF-kappaB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000034. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dey M, Ribnicky D, Kurmukov AG, Raskin I. In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity of a seed preparation containing phenethylisothiocyanate. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:326–333. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.096511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(−Delta Delta C) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC., Jr AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123:1939–1951. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharif MN, Tassiulas I, Hu Y, Mecklenbrauker I, Tarakhovsky A, Ivashkiv LB. IFN-alpha priming results in a gain of proinflammatory function by IL-10: implications for systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2004;172:6476–6481. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson WL, Van Eldik LJ. Inflammatory cytokines stimulate the chemokines CCL2/MCP-1 and CCL7/MCP-3 through NFkB and MAPK dependent pathways in rat astrocytes [corrected] Brain Res. 2009;1287:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy AJ, Ellacott KL, King VL, Hasty AH. Mouse models of the metabolic syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:156–166. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alviola JN, Jondiko T, Awika JM. Effect of Cross-Linked Resistant Starch on Wheat Tortilla Quality. Cereal Chemistry. 2010;87:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyangale EP, Mottram DS, Gibson GR. Gut microbial activity, implications for health and disease: the potential role of metabolite analysis. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:5573–5585. doi: 10.1021/pr300637d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou J, Martin RJ, Tulley RT, Raggio AM, Shen L, Lissy E, McCutcheon K, Keenan MJ. Failure to ferment dietary resistant starch in specific mouse models of obesity results in no body fat loss. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:8844–8851. doi: 10.1021/jf901548e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brahe LK, Astrup A, Larsen LH. Is butyrate the link between diet, intestinal microbiota and obesity-related metabolic diseases? Obesity Reviews. 2013;14:950–959. doi: 10.1111/obr.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vipperla K, O'Keefe SJ. The microbiota and its metabolites in colonic mucosal health and cancer risk. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:624–635. doi: 10.1177/0884533612452012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carding S, Verbeke K, Vipond DT, Corfe BM, Owen LJ. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26191. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v26.26191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Humphreys KJ, Conlon MA, Young GP, Topping DL, Hu Y, Winter JM, Bird AR, Cobiac L, Kennedy NA, Michael MZ, Le Leu RK. Dietary manipulation of oncogenic microRNA expression in human rectal mucosa: a randomized trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:786–795. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K, Kato T, Takahashi M, Fukuda NN, Murakami S, Miyauchi E, Hino S, Atarashi K, Onawa S, Fujimura Y, Lockett T, Clarke JM, Topping DL, Tomita M, Hori S, Ohara O, Morita T, Koseki H, Kikuchi J, Honda K, Hase K, Ohno H. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504:446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, Cheng G, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Ohba Y, Taniguchi T, Takeda K, Hori S, Ivanov, Umesaki Y, Itoh K, Honda K. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12204–12209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909122107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Louis P, Hold GL, Flint HJ. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:661–672. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez I, Kim J, Duffy PR, Schlegel VL, Walter J. Resistant starches types 2 and 4 have differential effects on the composition of the fecal microbiota in human subjects. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woo KS, Seib PA. Cross-linked resistant starch: Preparation and properties. Cereal Chemistry. 2002;79:819–825. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuentes-Zaragoza E, Riquelme-Navarrete MJ, Sanchez-Zapata E, Perez-Alvarez JA. Resistant starch as functional ingredient: A review. Food Research International. 2010;43:931–942. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lauw FN, Pajkrt D, Hack CE, Kurimoto M, van Deventer SJ, van der Poll T. Proinflammatory effects of IL-10 during human endotoxemia. J Immunol. 2000;165:2783–2789. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bussolati B, Rollino C, Mariano F, Quarello F, Camussi G. IL-10 stimulates production of platelet-activating factor by monocytes of patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122:471–476. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01392.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W, Lu L, Li Y, Fu F, Fung JJ, Thomson AW, Qian S. High-dose cellular IL-10 exacerbates rejection and reverses effects of cyclosporine and tacrolimus in Mouse cardiac transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:1081–1082. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(96)00412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takaoka A, Mitani Y, Suemori H, Sato M, Yokochi T, Noguchi S, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T. Cross talk between interferon-gamma and -alpha/beta signaling components in caveolar membrane domains. Science. 2000;288:2357–2360. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki M, Hisamatsu T, Podolsky DK. Gamma interferon augments the intracellular pathway for lipopolysaccharide (LPS) recognition in human intestinal epithelial cells through coordinated up-regulation of LPS uptake and expression of the intracellular Toll-like receptor 4-MD-2 complex. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3503–3511. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3503-3511.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saemann MD, Bohmig GA, Osterreicher CH, Burtscher H, Parolini O, Diakos C, Stockl J, Horl WH, Zlabinger GJ. Anti-inflammatory effects of sodium butyrate on human monocytes: potent inhibition of IL-12 and up-regulation of IL-10 production. FASEB J. 2000;14:2380–2382. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0359fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Naylor CP, Macfarlane GT. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut. 1987;28:1221–1227. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.10.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, Ward RE, Martin RJ, Lefevre M, Cefalu WT, Ye J. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:1509–1517. doi: 10.2337/db08-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baer DJ, Rumpler WV, Miles CW, Fahey GC., Jr Dietary fiber decreases the metabolizable energy content and nutrient digestibility of mixed diets fed to humans. J Nutr. 1997;127:579–586. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]