Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the influence of silver (Ag), zinc oxide (ZnO), and titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles on shear bond strength (SBS).

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and twenty extracted premolars divided into four groups with thirty specimens in each group. Group 1 (control): brackets (American Orthodontics) were bonded with Transbond XT primer. Groups 2, 3, and 4: brackets (American Orthodontics) were bonded with adhesives incorporated with Ag, ZnO, and TiO2 nanoparticles in the concentration of 1.0% nanoparticles of Ag, 1.0% TiO2, and 1.0% ZnO weight/weight, respectively. An Instron universal testing machine AGS-10k NG (SHIMADZU) was used to measure the SBS. The data were analyzed by SPSS software and then, the normal distribution of the data was confirmed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. One-way ANOVA test and Tukey's multiple post hoc procedures were used to compare between groups. In all statistical tests, the significance level was set at 5% (P < 0.05).

Results:

A significant difference was observed between control (mean [standard deviation (SD)] 9.43 [3.03], confidence interval [CI]: 8.30–10.56), Ag (mean [SD]: 7.55 [1.29], CI: 7.07–8.03), ZnO (mean [SD]: 6.50 [1.15], CI: 6.07–6.93), and TiO2 (mean [SD]: 6.33 [1.51], CI: 5.77–0.89) with SBS (F = 16.8453, P < 0.05) at 5% level of significance.

Conclusion:

Incorporation of various nanoparticles into adhesive materials in minimal amounts may decrease SBS and may lead to the failure of bracket or adhesive. The limitation of this study is that it is an in vitro research and these results may not be comparable to what the expected bond strengths observed in vivo. Further clinical studies are needed to evaluate biological effects of adding such amounts of nanoparticles and approve such adhesives as clinically sustainable.

Key words: Adhesive, nanoparticles, shear bond strength

INTRODUCTION

Despite the fact that use of nanotechnology in orthodontics is thought to be in its early stages, there is a gigantic potential in research related to this field including nanodesigned orthodontic bonding material and conceivable nanovector for quality conveyance for mandibular development incitement.[1]

Patient compliance in maintaining alluring oral hygiene is consistently confronting during orthodontic therapy; therefore, many practitioners prefer modalities that do not depend on patient cooperation. It is noted that both orthodontic appliances and bonding materials may retain plaque. The existence of archwires thwart cleaning by spawning difficulty in avenue to plaque-retaining areas; this is very much acclaimed while using multiple loops, auxiliary archwires, and diversity of elastics.[2] As a repercussion of this, demineralization supervened by white spot lesion and new sites liable to caries will form adjacent to the bands and brackets amid orthodontic treatment with fixed appliance.[3] Forestalling of white spot lesions eventuates by executing a good oral hygiene methods such as use of fluoridated dentifrice for brushing teeth.[4] Numerous methods have been used to curtail enamel demineralization in patients using fixed orthodontic appliances. These approaches include using bonding agents with antibacterial properties, mouth rinses incorporated with antimicrobial agents, and coatings on brackets/wires or remineralizing agents adjacent to orthodontic appliances, but their response was observed to be limited.[5,6] Nanotechnology has been applied in dentistry to cater materials with augmented mechanical properties and antibacterial effects.[7] With the evolution of nanotechnology and the contrasting demeanor disclose by nanoparticles, asserts have been contrived to take leverage of this approach in orthodontic bonding. An embodiment of nanoparticles into other orthodontic material has revealed promising accouterments in terms of antimicrobial and mechanical properties.[8] Nanoparticles are incorporated into orthodontic adhesives/cements or acrylic resins and can coated onto the surfaces of orthodontic appliances to prevent microbial adhesion or enamel demineralization in orthodontic therapy.[9] Incorporating nanoparticles within the bonding agent and not into the adhesive body itself has weighed a more convincing accession and in some way profitable from a clinical outlook. Considering that the bonding agent which comes into candid touch with the enamel surface, the destination area for precautionary pursuits. Studies in the literature established that nanofillers can minimize enamel demineralization with no arbitration of physical properties of the composite.[10] Researchers confirmed that experimental composites composed of silver nanoparticles (nAg) catered an admirable antibacterial properties without negotiating the shear bond strength (SBS).[11] However, inclusion of nAg may sequel to discoloration of the composite matrix, and there is a bit consideration in regard to their biocompatibility.[12] Copper- and zinc-based nanoparticles are reported to induce relentless noxious effects in animal studies in vitro.[13] In the recent past, there has been considerable scrutiny over regarding the photocatalytic action of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles in medical and dental literature.[14] Studies in the literature have reported that resins embodying TiO2 nanoparticles display compelling antimicrobial properties which may be applied for preventing recurrent caries and demineralization of the enamel.[15] Incorporation of TiO2 nanoparticles to dental composites also augmented mechanical properties, such as modulus of elasticity, microhardness, flexural strength, and also provided bond strength values that similar or even higher levels than that of the controls not containing the nanoparticles.[16] It has been mentioned in literature that various bonding manners need to confirm the prerequisites of the normal SBS ranging from 5.9 to 7.8 MPa.[17]

Previously, the SBS of a nanohybrid restorative material, Grandio (Voco, Germany), and traditional adhesive material (Transbond XT; 3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA) were analyzed when bonding orthodontic brackets and it was observed that nanofilled composite materials can possibly be utilized to bond orthodontic brackets to teeth if its consistency can be made more flowable to promptly hold adhere to the section base.[18]

As needs be, development of clinically adequate orthodontic adhesives with extra antimicrobial components could be attempted just if their mechanical properties have additionally been considered.

In a quickly developing universe of nanotechnology, the trust would be to get these innovations into clinical application at some point or another. Taking everything into account, the future in orthodontic treatment ought to advantage significantly through nanotechnology to all the present endeavors succeed to its clinical application at a sensible expense to the orthodontist and patients.

To the best of our knowledge, research in orthodontics on the proposed topic is limited to the fact that various nanoparticles have antibacterial activity. This study is an attempt to investigate and compare the influence of various nanoparticles on SBS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

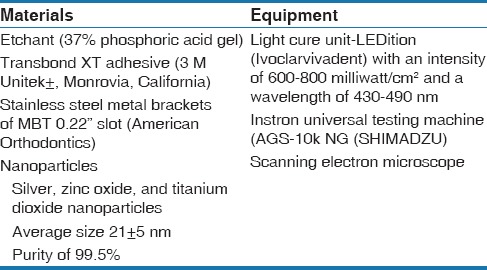

This was carried out at SVS Institute of Dental Sciences, India, after obtaining approval from the Ethical Clearance Committee. The material and equipment used in the study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Material and equipment used in the study

Sample for Test

120 noncarious, nonfluorosed extracted teeth

Preparation of the teeth: All the extracted teeth were stored in artificial saliva before testing. The teeth were mounted vertically on acrylic (methyl methacrylate self-cure resin) blocks that were color coded for identification, with only the crown portion exposed for the study. The whole sample was divided into four groups (GC of 30, GnAg of 30, GnZnO of 30, and GnTiO2 of 30)

Adhesive preparation: Vortex and IKA® T25 digital ULTRA-TURRAX® machine was used to blend three different nanoparticles (1.0% nAg), 1.0% nanoparticles of TiO2, 1.0% zinc oxide [ZnO], weight/weight) into the adhesive at 3400 rpm for 2 min in a dark room (Rotor stator mechanism). After the preparation, the adhesive was observed under scanning electron microscope to check the homogenicity of the mix.

Methodology

One hundred and twenty noncarious, nonfluorosed human premolar teeth extracted for orthodontic purpose were collected from the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, SVS Institute of Dental Sciences. Teeth with intact buccal surfaces and without any restoration, attrition, abrasion, erosion, or fracture, which have not been pretreated with any chemical agents, were included in the study.

All sample of teeth were cleaned with pumice and water for 5 s, rinsed for 10 s, air dried to avoid desiccation, and etched with 37% phosphoric acid for 30 s and rinsed with water for 10 s. The tooth surfaces were air dried till white, chalky surface appeared.

Samples in GC (control group of 30) were applied with smear of adhesive and light cured for 15 s

Samples in GnAg (nAg group of 30) were applied with smear of adhesive and light cured for 15 s

Samples in GnZnO (ZnO nanoparticles group of 30) were applied with smear of adhesive and light cured for 15 s

Samples in GnTiO2 (TiO2 nanoparticles group of 30) were applied with smear of adhesive and light cured for 15 s

Then, brackets were bonded on all the samples in all the groups and light cured for 40 s

The average surface area of the bonded bracket was 9.806 mm.

Evaluation of Shear Bond Strength

An “Instron” universal testing machine AGS-10k NG (SHIMADZU) was used to measure the SBS. The crosshead of Instron moved at the uniform speed of 1 mm/min. The acrylic block was positioned in the lower crosshead with the crown portion of teeth facing upward. The debonding force was applied in a direction parallel to the bracket base. A loop made of 0.8 mm stainless steel was attached to the upper crosshead to apply shear force to debond the bracket. The loop portion was attached below the gingival tie wing of the bracket. The data were analyzed by SPSS software (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 20.0, Chicago, Illinois, USA), and then the normal distribution of the data was confirmed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. One-way ANOVA test and Tukey's multiple post hoc procedures were used to compare between groups. In all statistical tests, the significance level was set at 5% (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

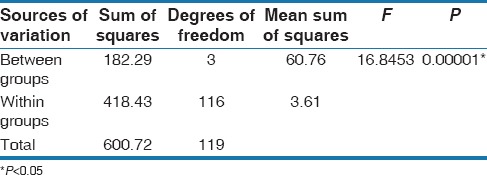

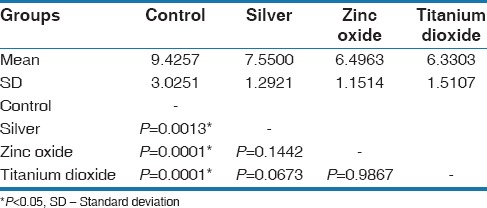

Scanning electron microscopy examination confirmed homogenous distribution of nanoparticles in the adhesive in all three groups. The mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence interval for mean of SBS in four groups is represented in Table 2. From the results of Table 3, it can be seen that a significant difference was observed between four groups (control, Ag, ZnO, and TiO2) with SBS (F = 16.8453, P < 0.05) at 5% level of significance. It means that the mean SBS was different in different groups. Further, to know the pairwise significant difference between two groups, the Tukey's multiple post hoc procedures were applied and the results are presented in Table 3. From the observation of Table 4, it can be derived that:

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence interval for mean of shear bond strength in four groups

Table 3.

Comparison of four groups (control, silver, zinc oxide, and titanium dioxide) with shear bond strength by one-way analysis of variance

Table 4.

Pair wise comparison of four groups (control, silver, zinc oxide, and titanium dioxide) with shear bond strength by Tukey's multiple post hoc procedures

A significant difference was observed between control and Ag groups (P = 0.0013), control and ZnO groups (P = 0.0001), control and TiO2 (P = 0.0001) at 5% level of significance, It means that the SBS was significantly higher in control as compared to Ag, ZnO, and TiO2 groups

A nonsignificant difference was observed between Ag and ZnO groups (P = 0.1442), Ag and TiO2 groups (P = 0.0673), and ZnO and TiO2 groups (P = 0.9867) at 5% level of significance. It means that the mean SBS was similar in Ag, ZnO, and TiO2 groups.

DISCUSSION

Orthodontic adhesives are acknowledged to display remarkable retaining amplitude of cariogenic streptococci in analogous with bracket materials. Incorporation of nAg into composite resins can minimize the clinging of cariogenic streptococci to orthodontic adhesives. Surface roughness performs an important aspect in the adhesion of bacteria.[19] The present study used nAg with concentration 1.0% in adhesive because nAg was shown to possess potent antibacterial properties. nAg was recently incorporated into dental resins. Their small particle size and large surface area could enable them to release more Ag ions at a low filler level, thereby reducing Ag particle concentration necessary for efficacy. The Ag ions in the resin agglomerated to form nanoparticles that became part of the resin.[19]

ZnO demonstrates antimicrobial property and has been applied in diversified disciplines, such as in creams and ointments which are indicated in management of foot ulcers, burns, and other traumatic skin injuries. Materials used in dentistry such as endodontic sealers and some of the cements have been availed for this same acumen.[20]

The concentration of TiO2 nanoparticles was selected according to the results of a previous study which revealed that incorporation of 1 weight% TiO2 nanoparticles to Transbond XT adhesive will bring significant antimicrobial properties without compromising the SBS. Previous researches showed that incorporation of 1 weight% TiO2 nanoparticles into a conventional orthodontic adhesive does not cause any additional adverse effects to the health when compared to those occurring with the use of pure resin. It is also quoted that periodic cautious steps must be undertaken when using nanocomposites and also their conventional counterparts, which include perfect removal of extra composite surrounding the bracket bases, especially in relation to the gingival and proximal contact areas and prevention of skin contact with resinous materials.[21]

TiO2 nanoparticles are commercially available in varying sizes and crystalline formats, are optimal for embodiment into dental materials. They are comparably economical with superlative mechanical properties and enticing color. The anatase aspect of TiO2 nanoparticles shows high photocatalytic action, in addition to carnage bacteria, fungi, and viruses.[22]

Studies have implied that the constitutional element of the antibacterial activity might be from the severance of the bacterial cell membrane function. In addition to this, investiture of intercellular reactive oxygen species, in conjunction with hydrogen peroxide, which is known as a strong oxidizing agent inimical to bacterial cells.[23]

Spencer et al. found that as the concentration of ZnO increases, SBS decreases. Mean bond strengths for the 13% and 23.1% ZnO mixtures were observed to be 5.04 MPa and 4.56 MPa, respectively in their study.[20] Jatania and Shivalinga also noted increased SBS with decreased concentration of ZnO. Keeping these facts in mind, we decided to use 1.0% ZnO.[24]

CONCLUSION

Incorporation of various nanoparticles into adhesive materials in minimal amounts can affect the SBS which may lead to the failure of bracket or adhesive. A significant difference in SBS was observed among three different nanoparticles. Further studies are needed to investigate effect of nanoparticles on other properties with different concentrations.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Riad M, Harhash AY, Elhiny OA, Salem GA. Evaluation of the shear bond strength of orthodontic adhesive system containing antimicrobial silver nano particles on bonding of metal brackets to enamel. Life Sci J. 2015;12:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artun J, Brobakken BO. Prevalence of carious white spots after orthodontic treatment with multibonded appliances. Eur J Orthod. 1986;8:229–34. doi: 10.1093/ejo/8.4.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorelick L, Geiger AM, Gwinnett AJ. Incidence of white spot formation after bonding and banding. Am J Orthod. 1982;81:93–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meeran NA. Iatrogenic possibilities of orthodontic treatment and modalities of prevention. J Orthod Sci. 2013;2:73–86. doi: 10.4103/2278-0203.119678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers C, Stewart S, Su B, Sandy J, Ireland A. Prevention and treatment of demineralisation during fixed appliance therapy: A review of current methods and future applications. Br Dent J. 2013;215:505–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beyling F, Schwestka-Polly R, Wiechmann D. Lingual orthodontics for children and adolescents: Improvement of the indirect bonding protocol. Head Face Med. 2013;9:27. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-9-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozak ST, Ozkan P. Nanotechnology and dentistry. Eur J Dent. 2013;7:145–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernández-Sierra JF, Ruiz F, Pena DC, Martínez-Gutiérrez F, Martínez AE, Guillén Ade J, et al. The antimicrobial sensitivity of Streptococcus mutans to nanoparticles of silver, zinc oxide, and gold. Nanomedicine. 2008;4:237–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borzabadi-Farahani A, Borzabadi E, Lynch E. Nanoparticles in orthodontics, a review of antimicrobial and anti-caries applications. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72:413–7. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2013.859728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia Y, Zhang F, Xie H, Gu N. Nanoparticle-reinforced resin-based dental composites. J Dent. 2008;36:450–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahn SJ, Lee SJ, Kook JK, Lim BS. Experimental antimicrobial orthodontic adhesives using nanofillers and silver nanoparticles. Dent Mater. 2009;25:206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wijnhoven SW, Peijnenburg WJ, Herberts CA, Hagens WI, Oomen AG, Heugens EH, et al. Nano-silver – A review of available data and knowledge gaps in human and environmental risk assessment. Nanotoxicology. 2009;3:109–38. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang B, Feng WY, Wang TC, Jia G, Wang M, Shi JW, et al. Acute toxicity of nano- and micro-scale zinc powder in healthy adult mice. Toxicol Lett. 2006;161:115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanone S, Rogerieux F, Geys J, Dupont A, Maillot-Marechal E, Boczkowski J, et al. Comparative toxicity of 24 manufactured nanoparticles in human alveolar epithelial and macrophage cell lines. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2009;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arai T, Ueda T, Sugiyama T, Sakurai K. Inhibiting microbial adhesion to denture base acrylic resin by titanium dioxide coating. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36:902–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poosti M, Ramazanzadeh B, Zebarjad M, Javadzadeh P, Naderinasab M, Shakeri MT. Shear bond strength and antibacterial effects of orthodontic composite containing TiO 2 nanoparticles. Eur J Orthod. 2013;35:676–9. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjs073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds J. A review of direct orthodontic bonding. Br J Orthod. 1975;2:171–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishara SE, Ajlouni R, Soliman MM, Oonsombat C, Laffoon JF, Warren J. Evaluation of a new nano-filled restorative material for bonding orthodontic brackets. World J Orthod. 2007;8:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miresmaeili A, Atai M, Mansouri K, Farhadian N. Effect of nanosilver incorporation on antibacterial properties and bracket bond strength of composite resin. Iran J Orthod. 2012;7:14–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spencer CG, Campbell PM, Buschang PH, Cai J, Honeyman AL. Antimicrobial effects of zinc oxide in an orthodontic bonding agent. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:317–22. doi: 10.2319/011408-19.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heravi F, Ramezani M, Poosti M, Hosseini M, Shajiei A, Ahrari F. In Vitro cytotoxicity assessment of an orthodontic composite containing titanium-dioxide nano-particles. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2013;7:192–8. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2013.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun J, Forster AM, Johnson PM, Eidelman N, Quinn G, Schumacher G, et al. Improving performance of dental resins by adding titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Dent Mater. 2011;27:972–82. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brayner R, Ferrari-Iliou R, Brivois N, Djediat S, Benedetti MF, Fiévet F. Toxicological impact studies based on Escherichia coli bacteria in ultrafine ZnO nanoparticles colloidal medium. Nano Lett. 2006;6:866–70. doi: 10.1021/nl052326h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jatania A, Shivalinga BM. An in vitro study to evaluate the effects of addition of zinc oxide to an orthodontic bonding agent. Eur J Dent. 2014;8:112–7. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.126262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]