Abstract

Objective:

Proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapy with two antibiotics for Helicobacter pylori eradication is widely accepted, but this combination fails in a considerable number of cases. Some studies have shown that cranberry inhibits the adhesion of a wide range of microbial pathogens, including H. pylori. The aim of this study was to assess the effect of cranberry on H. pylori eradication with a standard therapy including lansoprazole, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin (LCA) in patients with peptic ulcer disease (PUD).

Methods:

In this study, H. pylori-positive patients with PUD were randomized into two groups: Group A: A 14-day LCA triple therapy with 30 mg lansoprazole bid, 1000 mg amoxicillin bid, and 500 mg clarithromycin bid; Group B: A 14-day 500 mg cranberry capsules bid plus LCA triple therapy. A 13C-urea breath test was performed for eradication assessment 6 weeks after the completion of the treatment.

Findings:

Two hundred patients (53.5% males, between 23 and 77 years, mean age ± standard deviation: 50.29 ± 17.79 years) continued treatment protocols and underwent 13C-urea breath testing. H. pylori eradication was achieved in 74% in Group A (LCA without cranberry) and 89% in Group B (LCA with cranberry) (P = 0.042).

Conclusion:

The addition of cranberry to LCA triple therapy for H. pylori has a higher rate of eradication than the standard regimen alone (up to 89% and significant).

Keywords: Cranberry, eradication therapy, Helicobacter pylori

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative, spiral-shaped microorganism that infects approximately half of the world population.[1] Gastric infection by H. pylori is considered to be the most relevant cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric cancer.[2] Selection of the best drug regimens for eradication of H. pylori infection is already challenging. Antibiotic resistance due to frequent and uncontrolled use and the high prevalence of antibiotic side effects are the most common causes for treatment failure. To increase the eradication rates, as defined in the Maastricht IV report,[3] several clinical trials have been initiated involving extended treatment duration, the use of new antibiotics, or the addition of probiotics or other drugs to therapy.

There is a growing public interest for cranberry, blueberry, and relatively new gooseberry as a functional food because of the potential health benefits linked to phytochemical compounds responsible for secondary plant metabolites (flavonols, flavan-3-ols, proanthocyanidins, and phenolic acid derivatives).[4] Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.) is a member of the Ericaceae (the heath family). This fruit was collected from the wild by American Indians and used for a variety of purposes including as a preservative of fish and meat and medicinally as a poultice for dressing wounds.[5] Cranberry, in particular,[6,7] helps prevent urinary tract infections,[8,9,10] and has some anticancer properties.[11,12] Some studies have shown that cranberry juice constituents inhibit the adhesion of a wide range of microbial pathogens, including H. pylori, E. coli, oral bacteria, and influenza virus.[13] Cranberry proanthocyanidins can be used as an adjunct to increase intestinal secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) levels in mice receiving enteral nutrition.[14] The aim of this study was to compare the effect of cranberry on H. pylori eradication with a triple therapy including lansoprazole, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin (LCA) in patients with PUD.

METHODS

A prospective, open-label, randomized clinical trial study was conducted on 200 consecutive H. pylori-infected patients with PUD between June 2014 and September 2015. All of them were referred to our academic hospital in Gorgan (North of Iran). Exclusion criteria were previous H. pylori eradication, consumption of aspirin, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitors, warfarin, bismuth preparations, or antibiotics during the last 8 weeks. Patients with renal and hepatic impairment were not enrolled. Gastroscopy was done using a videoscope (Olympus GIF-XQ260, Japan), and two specimens were obtained from the antrum. H. pylori infection was diagnosed by histopathological examination. This research was approved by the Ethical Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

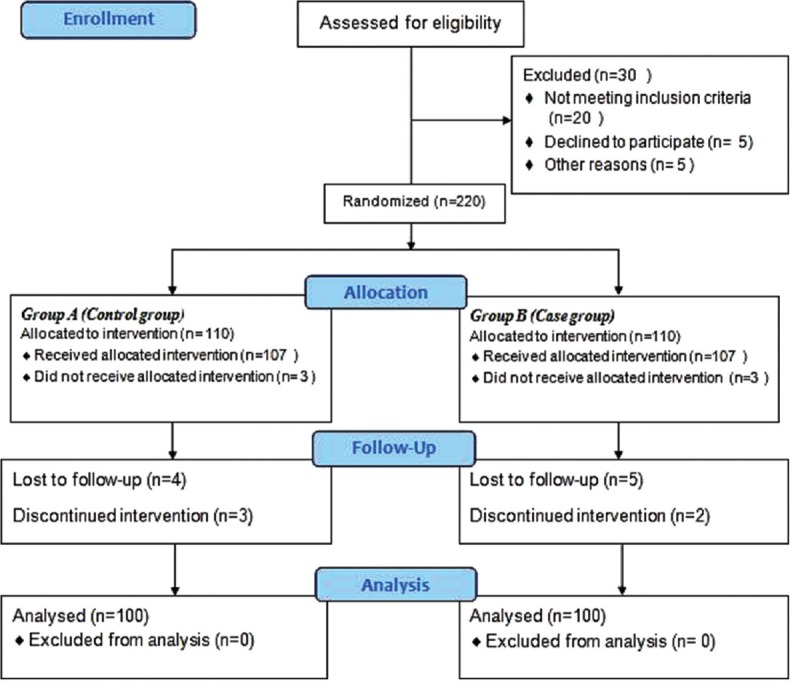

Initially, 250 patients were evaluated for inclusion, and finally, 200 patients were studied [Figure 1]. Patients were enrolled into one of the following groups: Group A (control group, n = 100): The patients were given a 14-day standard LCA triple therapy for H. pylori infection eradication with 30 mg lansoprazole (Lanzo Doctor Abidi Company) bid, 1000 mg amoxicillin bid, and 500 mg clarithromycin bid; Group B (case group, n = 100): In this group, the patients were given a 14-day 500 mg cranberry capsules (Liver Company, Canada) bid plus LCA triple therapy. Patients were asked to return at the end of the treatment to assess the compliance with therapy that was defined as consumption of >80% of the prescribed drugs. A 13C-urea breath test was performed for H. pylori eradication assessment 6 weeks after the completion of the treatment.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study

Statistical analysis was performed using Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, and one-way analysis of variance test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the data were analyzed using SPSS 18 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and the values were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

RESULTS

Two hundred patients (53.5% males, between 23 and 77 years, mean age ± SD: 50.29 ± 17.79 years) continued treatment protocols and underwent 13C-urea breath testing. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding age, gender, and body mass index. H. pylori eradication was achieved in 74% patients in Group A (LCA without cranberry) and 89% patients in Group B (LCA with cranberry). The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.042) [Table 1]. As shown in this table, there was no significant difference between the study groups in the rate of H. pylori eradication on the basis of sex (P = 0.912 for standard LCA therapy and P = 0.785 for LCA with cranberry).

Table 1.

Helicobacter pylori eradication rates of study subjects in two groups

DISCUSSION

In vitro studies have shown that cranberry juice inhibits the adhesion of microbial pathogens, including H. pylori, uropathogenic E. coli, oral bacteria, and influenza virus.[13] Cranberry proanthocyanidins can be used as an adjunct to increase intestinal sIgA levels in mice receiving enteral nutrition.[14] A clinical investigation found that consuming a cranberry for 10 weeks resulted in a 5-fold increase in proliferation of T cells, a 30% increase in NK cell proliferation, and a 20% reduction in interleukin 17 secretion, as well as a significant reduction in cold and flu symptoms compared to placebo.[15] Nantz et al. reported that consumption of the cranberry modified the ex vivo proliferation of γδ-T cells. As these cells are located in the epithelium and serve as the first line of defense, improving their function may be related to reducing the number of symptoms associated with infection.[16]

Some studies showed that cranberry inhibited the adhesion of two-thirds of tested clinical isolates of H. pylori including bacteria expressing sialic acid-specific adhesion, and researchers hypothesized that cranberry juice might have the ability to eradicate H. pylori in vivo.[17,18] However, cranberry juice in a mice model of H. pylori infection caused a significant clearance of the H. pylori mass; however, it had no effect on eradicating the pathogen from the gastric lumen.[19] In one study, cranberry juice alone accounted for a 15% of the H. pylori eradication, compared to 5% for placebo. Although this effect was significant, the rate of eradication was still considerably lower than that of conventional therapy.[20]

Here, we reported that adding cranberry capsules to the standard regimen for treating H. pylori has a higher rate of eradication than the standard regimen alone (up to 89% and significant). Assessment of cranberry extract and probiotics[21] showed that the combination of the cranberry with a probiotic is the most effective treatment in H. pylori in children. Zhang et al. used cranberry juice for treatment of H. pylori in adults for 90 days and reported that regular consumption of cranberry juice could suppress H. pylori infection in endemically afflicted populations.[20] In another study, adding cranberry juice to the standard treatment improves the rate of H. pylori eradication in females;[13] however, in our study, there was no significant difference between two groups in the rate of H. pylori eradication on the basis of sex.

This study indicated a potential beneficial effect of cranberry in increasing the rate of H. Pylori eradication; however, the results shown here are only preliminary, and further studies are necessary. Two-week cranberry consumption is an inexpensive and available supplement; however, cranberry is a native North America plant, and in Iran, the only form available is capsules. In most of the studies, juice and dried fruit of cranberry were used and maybe the capsule forms are not as effective as the other forms. Further assessment for defining the best form of cranberry for different clinical situations is necessary.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

Mohammadreza Seyyedmajidi: Reviewing of literature, Study design, Data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation Reviewing of literature and manuscript editing. Anahita Ahmadi: Reviewing of literature, Data collection, Shahin Hajiebrahimi: Reviewing of literature, Data collection, Seyedali Seyedmajidi: Reviewing of literature, Data collection, Majid Rajabikashani: Reviewing of literature, Data collection, Mona Firoozabadi: Reviewing of literature, Data collection, Jamshid Vafaeimanesh: Reviewing of literature, Study design, and manuscript editing.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Golestan Research Center of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. We wish to thank all the researchers who took part in this research project and Doctor Abidi Company members for drugs provision.

REFERENCES

- 1.Correa P, Houghton J. Carcinogenesis of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:659–72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seyedmajidi S, Mirsattari D, Zojaji H, Zanganeh E, Seyyedmajidi M, Almasi S, et al. Penbactam for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A randomised comparison of quadruple and triple treatment schedules in an Iranian population. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2013;14:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection – the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–64. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namiesnik J, Vearasilp K, Nemirovski A, Leontowicz H, Leontowicz M, Pasko P, et al. In vitro studies on the relationship between the antioxidant activities of some berry extracts and their binding properties to serum albumin. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;172:2849–65. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0712-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seeram NP. Berry fruits: Compositional elements, biochemical activities, and the impact of their intake on human health, performance, and disease. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:627–9. doi: 10.1021/jf071988k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polashock J, Zelzion E, Fajardo D, Zalapa J, Georgi L, Bhattacharya D, et al. The American cranberry:First insights into the whole genome of a species adapted to bog habitat. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:165. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan X, Murphy BT, Hammond GB, Vinson JA, Neto CC. Antioxidant activities and antitumor screening of extracts from cranberry fruit (Vaccinium macrocarpon) J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:5844–9. doi: 10.1021/jf0202234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell AB, Vorsa N, Der Marderosian A, Foo LY. Inhibition of the adherence of P-fimbriated Escherichia coli to uroepithelial-cell surfaces by proanthocyanidin extracts from cranberries. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1085–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell AB. Cranberry proanthocyanidins and the maintenance of urinary tract health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2002;42(3 Suppl):273–8. doi: 10.1080/10408390209351915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vorsa N, Polashock J, Howell A, Cunningham D, Roderick R. Evaluation of fruit chemistry in cranberry germplasm: Potential for breeding varieties with enhanced health constituents. Acta Hortic. 2002;574:215–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neto CC. Cranberries: Ripe for more cancer research? J Sci Food Agric. 2011;91:2303–7. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh AP, Singh RK, Kim KK, Satyan KS, Nussbaum R, Torres M, et al. Cranberry proanthocyanidins are cytotoxic to human cancer cells and sensitize platinum-resistant ovarian cancer cells to paraplatin. Phytother Res. 2009;23:1066–74. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shmuely H, Yahav J, Samra Z, Chodick G, Koren R, Niv Y, et al. Effect of cranberry juice on eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients treated with antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51:746–51. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierre JF, Heneghan AF, Feliciano RP, Shanmuganayagam D, Krueger CG, Reed JD, et al. Cranberry proanthocyanidins improve intestinal sIgA during elemental enteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38:107–14. doi: 10.1177/0148607112473654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nantz MP, Rowe CA, Muller CE, Creasy R, Chapkin C, Pasqualini S, et al. Cranberry phytochemicals modify human immune function and appear to reduce the severity of cold and flu symptoms. FASEB J. 2010;24:326–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nantz MP, Rowe CA, Muller C, Creasy R, Colee J, Khoo C, et al. Consumption of cranberry polyphenols enhanceshuman γδ-T cell proliferation and reduces the number of symptoms associated with colds and influenza: A randomized, placebo-controlled intervention study. Nutr J. 2013;12:161–70. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ofek I, Goldhar J, Sharon N. Anti-Escherichia coli adhesin activity of cranberry and blueberry juices. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;408:179–83. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0415-9_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell AB, Reed JD, Krueger CG, Winterbottom R, Cunningham DG, Leahy M. A-type cranberry proanthocyanidins and uropathogenicbacterial anti-adhesion activity. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2281–91. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi T, Xiao SD. Cranberry juice cocktail for prevention and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in mice model. Chin J Gastroenterol. 2003;8:265–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Ma J, Pan K, Go VL, Chen J, You WC. Efficacy of cranberry juice on Helicobacter pylori infection: A double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Helicobacter. 2005;10:139–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gotteland M, Brunser O, Cruchet S. Systematic review: Are probiotics useful in controlling gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1077–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]