Abstract

Objective:

The principal aim of this study was to explore the self-perception of clinical pharmacists of their impact on healthcare in Khartoum State, Sudan, how they think doctors perceive their impact, exploring the obstacles that clinical pharmacists are facing, and identifying what clinical pharmacists recommend for a better clinical pharmacy practice in Sudan.

Methods:

This was an exploratory cross-sectional study that employed a qualitative method. Individual, in-depth interviews were conducted with a convenient sample of 26 clinical pharmacists working in 14 governmental hospitals in Khartoum State, Sudan, in March 2016. Each interview was recorded, transcribed, and coded into themes. Thematic analysis was carried out.

Findings:

The study revealed different themes regarding clinical pharmacists' perception of their impact on healthcare. The majority believed that they made an improvement in healthcare but not to the level they aspire to. Participants expressed that junior doctors and nurses had a better acceptance of clinical pharmacists' interventions compared to senior doctors. The main obstacles that clinical pharmacists were facing were their limited number, lack of support from health authorities, lack of training and educational program, lack of job descriptions, lack of specific area in patient files for clinical pharmacist intervention, and low salaries. Most participants showed dissatisfaction with the syllabus of the master of clinical pharmacy they studied.

Conclusion:

The study revealed that clinical pharmacists were looking for a better contribution in healthcare in Sudan. This can be achieved by solving the problems identified in this study.

Keywords: Clinical pharmacists, doctors' perception, impact on healthcare, self-perception

INTRODUCTION

For many years, it was the physician's role to diagnose the disease and write the prescription; while the pharmacist's role was only limited to compound and dispense these prescriptions.[1] This practice has changed when clinical pharmacy commenced. Clinical pharmacy is a health science through which the clinical pharmacists optimize the use of medications, promote wellness, and prevent disease.[2] The concept of clinical pharmacy was announced as a “hot new trend” in the 1960s by pharmacy educators as a new type of pharmacy practice, which is patient oriented rather than drug oriented.[3,4]

Al Hamarneh et al. affirmed that clinical Pharmacists' interventions helped to minimize the incidence of death through several activities such as evaluation of drug utilization, providing educational services for patients, monitoring drug interactions, management of drug protocols, participating in medical rounds, and completion of admission drug histories.[5]

Clinical pharmacists are crucial to promote the rational use of medications.[2] They enhance the quality of patient care as they are the primary sources of valid and updated information regarding the safe, cost-effective, and rational use of medications.[1] Chisholm-Burns et al. mentioned that incorporating clinical pharmacists as healthcare team members is a viable solution to improve the quality of healthcare.[6]

The impact of clinical pharmacists' interventions was evidenced in several specialties. Khalili et al. identified that clinical pharmacists in Iran enhanced the knowledge of physicians regarding adverse drug reactions.[7] Khan Mohammed et al. highlighted that clinical pharmacists' interventions in patients with diabetic nephropathy were effective in preventing the deterioration of renal function through patient counseling.[8] Dashti-Khavidaki et al. stated that knowledge and practice of nurses regarding medications delivery via enteral catheters were significantly improved via clinical pharmacists lead educational programs.[9] Loewen et al. revealed that the greater the time clinical pharmacists spent on clinical services, the better was their impact on healthcare.[10]

In many countries, the relationship between clinical pharmacists and physicians is not ideal.[1] In Nigeria, clinical pharmacists are having difficulty in establishing their identities as other healthcare professionals view their role as dispensers only.[11] This is not limited only to developing countries as Rosenthal et al. mentioned that the limited support from physicians is one of the obstacles to the practice of clinical pharmacists in Canada.[12] It was revealed that the main challenges that clinical pharmacists face are billing for service, reimbursement, work overload, acceptance by other healthcare providers, lack of knowledge, lack of training, and documentation.[13,14]

For clinical pharmacists to practice in the best of their abilities, they should have had good clinical pharmacy education as well as hospital training. Berhane et al. stated that the majority of physicians in Ethiopia expect clinical pharmacists are knowledgeable drug experts.[15]

The American College of Clinical Pharmacy highlighted the importance of quality assurance of the clinical services that the clinical pharmacists offer.[16]

Clinical pharmacy commenced in Sudan in 2001 as a subject in the undergraduate pharmacy curriculum. Postgraduate clinical pharmacy education was started in 2004 as a “2-year” master program. Thereafter, postgraduate clinical pharmacy education expanded further as several universities started master in clinical pharmacy programs.[17] Unfortunately, unavailability of facilities, absence of resources, and unavailability of qualified and well-trained clinical pharmacists all challenge the success of clinical pharmacy education in Sudan.[17]

Currently, more than a hundred of clinical pharmacists are being graduated every year in Sudan. However, their impact on healthcare was never assessed. The principal aim of this study was to explore the self-perception of clinical pharmacists regarding their impact on healthcare in Khartoum State, Sudan, how they think doctors perceive their impact, exploring the obstacles that clinical pharmacists are facing, and identifying what clinical pharmacists recommend for a better clinical pharmacy practice in Sudan.

METHODS

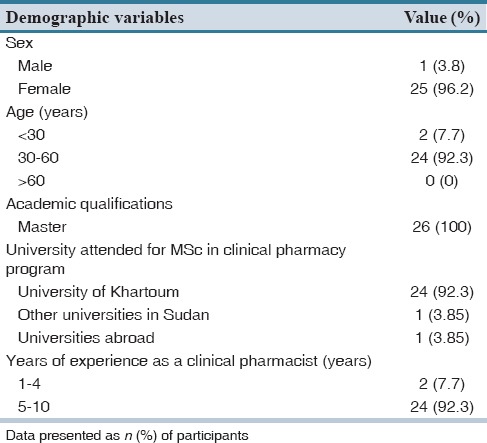

This is a qualitative, cross-sectional, exploratory study that was conducted in March 2016 in Khartoum State, Sudan. In-depth individual telephone interviews were conducted with a convenient sample of 26 clinical pharmacists [Table 1] from 14 governmental teaching hospitals in Khartoum State, Sudan.

Table 1.

Participants' demographic data

A convenient sampling technique was used. The study was designed to explore views rather than to assume representativeness.[18] E-mail invitations for participation in the study were sent to the list of clinical pharmacists in Khartoum State that was obtained from the Ministry of Health. The list contained the names of 85 clinical pharmacists. However, E-mails were provided for 69 pharmacists only. Invitation E-mails to participate in the study were sent to the whole list; nevertheless, only twenty pharmacists accepted to participate. Interview arrangements were made with those who agreed to participate. The interviews were held at the place of work of each clinical pharmacist. The stopping criterion for data collection was to stop when no new themes emerge from the interviews. After interviewing the twenty pharmacists and for the purpose of data saturation, further new participants were contacted and they agreed to participate. The new participants were introduced by resending E-mail invitations to the whole list of clinical pharmacists excluding those who already accepted to participate. Eight pharmacists agreed to participate, and those who responded earlier were contacted first.

When three of the new participants were interviewed, some new themes did emerge. However, when another three participants were interviewed, no new themes emerged. At this point, data saturation was thought to be reached.[18] Covering letters containing information about the aim of the study were given to participants, and informed consent was obtained from each one.

One investigator conducted all the interviews to ensure consistency in data collection, and all interviews were conducted in the English language. The average length of each interview was between 30 and 45 min. A simple checklist of topics (rough topic guide) was used to begin and guide the conversations [Supplementary Table 1 (515.8KB, tif) ]. Probing and subsequent questions were developed during the interviews depending on participants' answers.

Interviews main questions

Notepapers and audiotape recording were used to collect the data, which was then transcribed. Transcripts were produced in English and subsets were shown to interviewees to assess for the accuracy of content before analysis to ensure data credibility.[18] The interviews were coded using thematic analysis. Manual categorization was used and categorization continued till all themes were identified.[18]

To guarantee reliability and to allow for different perspectives, the field data were listened to, viewed, and coded by the first author to ensure consistency in coding. The second author independently assessed all codes. The two categorizations were then compared and any discrepancy was discussed and the final categorization was agreed on. Thematic analysis was carried out.[18]

Computerized research records were stored in a password-protected computer while the hard copies were stored under lock and key. Data were protected effectively against improper disclosure when received, transmitted, and stored. The Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Khartoum Ethics Committee approved this study in January 2016.

RESULTS

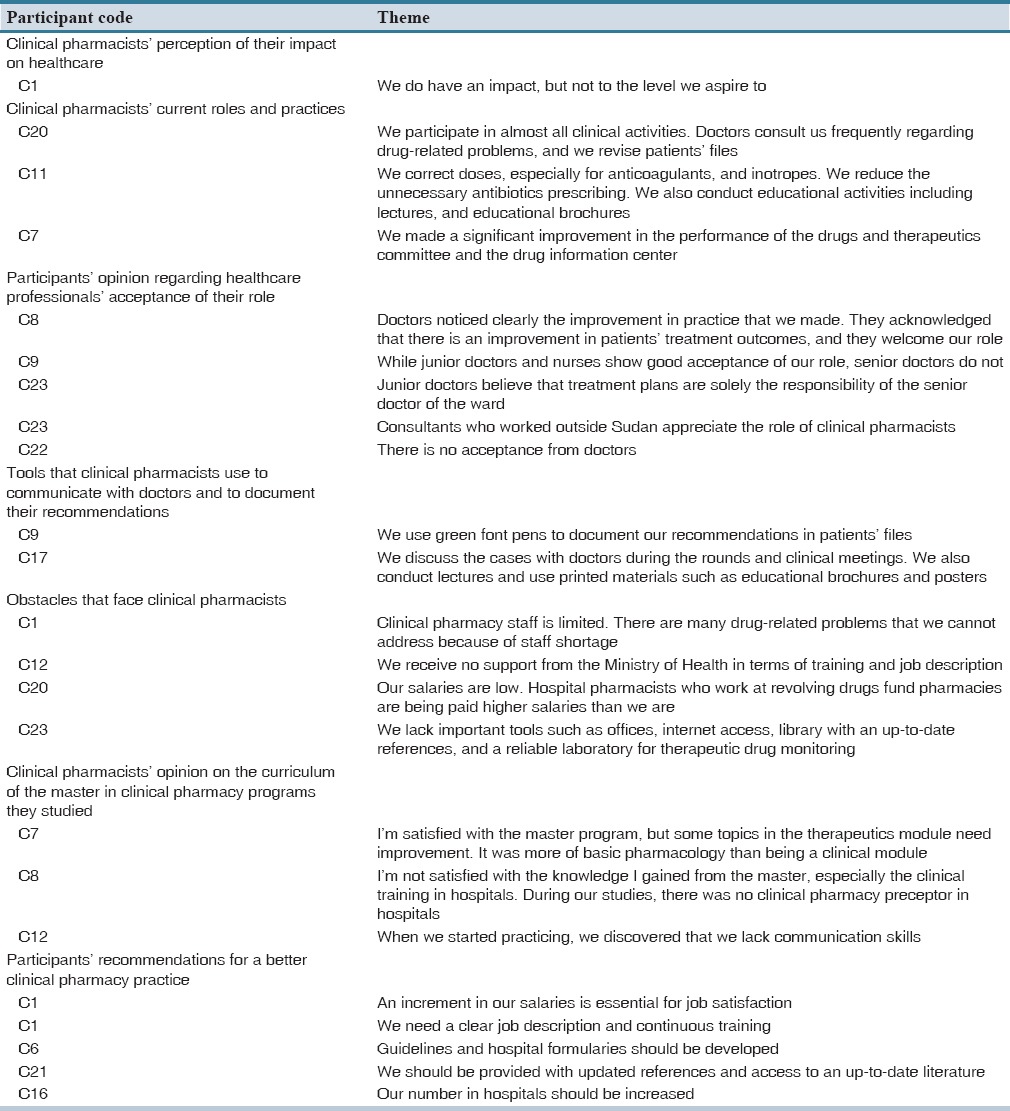

The paper revealed different themes regarding how clinical pharmacists perceive their impact on healthcare in Khartoum State, Sudan. It highlighted how they think other healthcare professionals perceive their impact. The paper also explored the tools that clinical pharmacists are using to communicate with doctors and in what form do clinical pharmacists give their recommendations. It identified the obstacles and challenges that clinical pharmacists are facing. Besides, this study also examined the opinion of clinical pharmacists on the curriculum of the master in clinical pharmacy programs they studied. The paper also explored their recommendations for a better clinical pharmacy practice. Participants were coded using the letter “C” followed by a number. The demography of the participants is shown in Table 1, and the main themes are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The main themes of the results

The majority of participants affirmed that they did have an impact on healthcare but not to the level they aspire to:

“We do have an impact, but not to the level we aspire to” – C1.

“To some extent, yes. We did positively impact healthcare, but we are only three clinical pharmacists and it is difficult for us to cover all aspects of the clinical pharmacy practice” – C25.

Participants identified different roles that they practice at their hospitals including patients' medications review, correcting medications errors, participating in daily medical rounds, participating in developing treatment plans, observing drug-drug interactions and adverse drug reactions, conducting therapeutic drug monitoring, developing guidelines, and offering patients counseling. Results showed variations in clinical pharmacy practice among the different hospitals. This may reflect the absence of central direction from health authorities:

“We correct doses, especially for anticoagulants, and inotropes. We reduce the unnecessary antibiotics prescribing. We also conduct educational activities including lectures, and educational brochures” – C11.

“We participate in almost all clinical activities. Doctors consult us frequently regarding drug-related problems, and we revise patients' files” – C20.

Participants also mentioned that they made an improvement in the performance of drugs and therapeutics committees, and the drug information centers:

“We made a significant improvement in the performance of the drugs and therapeutics committee and the drug information center” – C7.

Clinical pharmacists varied in their opinion regarding healthcare professionals' acceptance of their role. The majority of participants mentioned that while nurses and junior doctors have good acceptance of their roles, senior doctors do not. This might be due to egotism of some senior doctors:

“…Doctors noticed clearly the improvement in practice that we made. They acknowledged that there is an improvement in patients' treatment outcomes, and they welcome our role” – C8.

“While junior doctors and nurses show good acceptance of our role, senior doctors do not” – C9.

On the other hand, some pharmacists mentioned that junior doctors usually follow the practice of the senior doctor of the ward. Physicians who practiced outside Sudan have already been exposed to clinical pharmacists and are familiar with the concept of clinical pharmacy:

“Junior doctors believe that treatment plans are solely the responsibility of the senior doctor of the ward. Generally, consultants appreciate the role of clinical pharmacists, especially those who worked outside Sudan” – C23.

Only one pharmacist mentioned that there are no acceptance and cooperation from doctors at all:

“There is no acceptance from doctors” – C22.

Most of the participants revealed that the main tool of interaction between clinical pharmacists and doctors was the verbal discussion during clinical meetings. Besides, they use some printed materials such as educational brochures and posters.

“We discuss the cases with doctors during the rounds and clinical meetings. We also conduct lectures and use printed materials such as educational brochures and posters” – C17.

One clinical pharmacist mentioned that they use green font pens to write their recommendations in patients' files.

“We use green font pens to document our recommendations in patients' files” – C9.

Clinical pharmacists described several obstacles that they have been facing. They mentioned repetitively the lack of a specific section in patients' files for them. They also mentioned the lack of training and the lack of continuous educational programs. The limited number of clinical pharmacists in hospitals was found to be among the key obstacles. Moreover, there was a lack of important facilities such as offices, libraries with up-to-date references, and Internet access. Besides, there are no national standard treatment guidelines or hospital formularies to benchmark doctors' practices against. Clinical pharmacists also mentioned the lack of support from health authorities in terms of coordination with hospitals' management and providing clear job descriptions. Clinical pharmacists' salaries were described to be insufficient:

“Clinical pharmacy staff is limited. There are many drug-related problems that we cannot address because of staff shortage” – C1.

“Our salaries are low. Hospital pharmacists who work at revolving drugs fund pharmacies are being paid higher salaries than we are” – C20.

“We receive no support from the Ministry of Health in terms of training and job description” – C12.

“We lack important tools such as offices, internet access, library with an up-to-date references, and a reliable laboratory for therapeutic drug monitoring” – C23.

Participants showed significant variation in their assessment of the syllabus of the clinical pharmacy master programs they had. The majority of them revealed that it has important gaps that need to be addressed. They highlighted that the syllabus needs revision and amendments. Besides, they identified the need for improving the way of teaching. They also identified that the training period in hospitals was short. Clinical pharmacists described the therapeutics module as being more pharmacological than clinical. Besides, they highlighted that the content of the communication skills subject they studied during the master program was insufficient:

“Yes, it was good. I'm satisfied with the master program, but some topics in the therapeutics module need improvement. It was more of basic pharmacology rather than being a clinical module” – C7.

“I'm not satisfied with the knowledge I gained from the master, especially the clinical training in hospitals and the module of therapeutics. During our studies, there was no clinical pharmacy preceptor in hospitals, but I think this problem was solved” – C8.

“When we started practicing, we discovered that we lack communication skills” – C11.

Participants recommended continuous educational and training programs. They strongly recommended increasing the number of clinical pharmacists in hospitals. Revisiting the master in clinical pharmacy syllabus was found to be of crucial importance. Participants also highlighted the importance of clinical pharmacy subspecialties. Besides, clinical pharmacists described the importance of clear job description and implementation guidance from health authorities. Increment in salaries was described as an important tool to ensure better practice:

“Our number in hospitals should be increased” – C16.

“We need a clear job description, an increment in our salaries, and continuous training” – C1.

“Guidelines and hospital formularies should be developed” – C6.

“We should be provided with updated references, and access to an up-to-date literature” – C21.

DISCUSSION

The paper identified different themes regarding clinical pharmacists' perception of their impact on healthcare in Khartoum State, Sudan. Most participants mentioned that they have positively impacted healthcare. However, they consider this as not to the level they aspire to. Similar studies that were performed in other countries also emphasized that clinical pharmacists did improve the quality of healthcare. In his paper, Lipton et al. revealed that clinical pharmacists improved the appropriateness of geriatric drug prescribing in outpatient settings.[19]

Proper et al. studied the impact of clinical pharmacists in the emergency department (ED) of an Australian public hospital. The study revealed that after the implementation of the clinical pharmacy services at the ED, the percentage of medication errors decreased by 11%. About 59% of ED pharmacists' medication interventions were clinically significant.[20]

Moreover, studies also showed that clinical pharmacists have potential in reducing the unnecessary healthcare expenditures arising from drug-related problems. Lucca et al. found that clinical pharmacists in intensive care settings made 117 recommendations, of which 94% was accepted. The total net annualized cost savings made was 135205.22 USD.[21]

Clinical pharmacists showed different views regarding healthcare professionals' acceptance of their role. The majority of them mentioned that nurses and junior doctors have good perceptions of their roles while senior doctors do not. In a previous study in Sudan, Abdalla et al. assessed the perception of physicians about clinical pharmacists' role in 28 hospitals. Of the total participants, 92.3% believed that clinical pharmacists are important healthcare team members.[14]

Similar studies that were conducted outside Sudan also revealed the high acceptance of junior doctors and nurses for the role of clinical pharmacists. In the United Arab Emirates, Ibrahim and Ibrahim revealed that two-thirds of the physicians believed that pharmacists could act as a reliable source of general drug information and play an important role in discovering drug-related problems. It was found that the junior physicians had more appreciation to clinical pharmacists.[1]

In Egypt, Sabry and Farid found that 50.5% of physicians reported that clinical pharmacists are their first source of information about drugs. Moreover, about one-third of physicians believed that pharmacists could be a reliable source of clinical information, identify drug-related problems, or advise the physicians about medication's cost effectiveness.[22]

Concerning the master in clinical pharmacy programs, most of the participants showed dissatisfaction with the syllabus and training. No previous studies in Sudan assessed this issue. Mohamed reported that parallel to the introduction of the clinical pharmacy master program at the University of Khartoum, the pharmacy of Soba Hospital, Khartoum University's Teaching Hospital, was restructured to introduce more clinical services. This was considered as a major breakthrough in hospital pharmacy service upgrading in Sudan.[17]

Clinical pharmacists described different obstacles and challenges in our study. Studies in other countries showed some similarities to our study including work overload and acceptance of doctors. Hale et al. stated that the main challenges that clinical pharmacists face are billing for service, reimbursement, work overload, acceptance by other healthcare providers, and documentation.[13] Abdalla et al. pointed out that barriers to the practice of clinical pharmacy are time constraints, lack of self-confidence, lack of knowledge, lack of training, staff shortage, and lack of facilities.[14]

The issue of the lack of regulations and support from health authorities was even reported in developed countries. In the UK, for example, it was found that clinical pharmacy is not practiced in a uniform manner in hospitals. The absence of central direction by the profession and the Department of Health has enabled this diversity to flourish.[23]

Although many studies explored physicians' perception about the role and impact of clinical pharmacists, to the best of our knowledge, this paper was the first one that explored the self-perception of clinical pharmacists of their impact on healthcare and how they think other healthcare professionals perceive their role. Moreover, it was the first one that assessed the master of clinical pharmacy programs from clinical pharmacists' perspectives. The study did not explore the impact of clinical pharmacists from the perspectives of other stakeholders such as the doctors and patients. This might be a potential area for future research.

The study revealed that clinical pharmacists made a positive impact in improving the quality of healthcare in Sudan; however, this was not to the level clinical pharmacists aspire to.

Moreover, there is a considerable variation in the impact of clinical pharmacists on healthcare from one hospital to the other hospitals. Clinical pharmacists are looking for better practices, which can be achieved by addressing the different obstacles that are facing them. Providing continuous educational and training programs, specific sections in patients' files to document pharmacists' recommendations, increasing doctors' awareness about the role of clinical pharmacists, and addressing the gaps in the master of clinical pharmacy programs are of crucial importance.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

All authors' contribution adheres to the International Committee of Medical Journals editors' definition of authorship. Mr. Anas Mustafa Ahmed Salim developed the concept, designed the study, carried the categorization, and drafted the article. Ms. Arwa Hassan Ahmed Elhada carried the categorization and participated in drafting the article. Mr. Bashir Elgizoli collected the data and redrafted the article. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors had full access to the data that support the publication.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ibrahim O, Ibrahim R. Perception of physicians to the role of clinical pharmacists in United Arab Emirates (UAE) Sci Res. 2014;5:895–902. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu-Gharbieh E, Fahmy S, Rasool BA, Abduelkarem A, Basheti I. Attitudes and perceptions of healthcare providers and medical students towards clinical pharmacy's services in United Arab Emirates. Trop J Pharm Res. 2010;9:421–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobbell DA. Clinical pharmacy: An example of interprofessional education in the late 1960s and 1970s. Nurs Hist Rev. 2016;24:98–102. doi: 10.1891/1062-8061.24.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamadi S, Mohammed M, Dizaye K, Basheiti I. Perceptions, experiences and expectations of physicians regarding the role of the pharmacist in an Iraqi hospital setting. Trop J Pharm Res. 2014;14:293–301. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Hamarneh YN, Rosenthal M, McElnay JC, Tsuyuki RT. Pharmacists' perceptions of their professional role: Insights into hospital pharmacy culture. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2011;64:31–5. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v64i1.984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chisholm-Burns MA, Kim Lee J, Spivey CA, Slack M, Herrier RN, Hall-Lipsy E, et al. US pharmacists' effect as team members on patient care: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Med Care. 2010;48:923–33. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e57962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalili H, Mohebbi N, Hendoiee N, Keshtkar AA, Dashti-Khavidaki S. Improvement of knowledge, attitude and perception of healthcare workers about ADR, a pre- and post-clinical pharmacists' interventional study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000367. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan Mohammed A, Medarametla C, Rabbani MM, Prashanthi K. Role of a clinical pharmacist in managing diabetic nephropathy: An approach of pharmaceutical care plan. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:82. doi: 10.1186/s40200-015-0213-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dashti-Khavidaki S, Badri S, Eftekharzadeh SZ, Keshtkar A, Khalili H. The role of clinical pharmacist to improve medication administration through enteral feeding tubes by nurses. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34:757–64. doi: 10.1007/s11096-012-9673-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loewen P, Merrett F, Lemos JD. Pharmacists' perceptions of the impact of care they provide. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2010;8:89–95. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552010000200002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auta A, Strickland-Hodge B, Maz J. Challenges to clinical pharmacy practice in Nigerian hospitals: A qualitative exploration of stakeholders' views. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jep.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenthal M, Austin Z, Tsuyuki R. Are pharmacists the ultimate barrier to pharmacy practice change? Can Pharm J. 2010;143:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hale J, Murawski M, Ives T. Challenges to clinical pharmacy practice in Nigerian hospitals: A qualitative exploration of stakeholders' views. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013;53:640–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdalla AA, Adwi GM, Al-Mahdi AF. Physicians' perception about the role of clinical pharmacists and potential barriers to clinical pharmacy. World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;4:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berhane A, Ali E, Odegard P, Suleiman S. Physicians expectations of clinical pharmacists' role in Jimma University Specialized Hospital, South Ethiopia. Int J Pharm Teach Pract. 2013;4:571–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saseen JJ, Grady SE, Hansen LB, Hodges BM, Kovacs SJ, Martinez LD, et al. Future clinical pharmacy practitioners should be board-certified specialists. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1816–25. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.12.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohamed SS. Current state of pharmacy education in the Sudan. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75:65a. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75465a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowling A. Research Methods in Health: Investigating Health and Health Services. Philadelphia: Open University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipton HL, Bero LA, Bird JA, McPhee SJ. The impact of clinical pharmacists' consultations on physicians' geriatric drug prescribing. A randomized controlled trial. Med Care. 1992;30:646–58. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proper JS, Wong A, Plath AE, Grant KA, Just DW, Dulhunty JM. Impact of clinical pharmacists in the emergency department of an Australian public hospital: A before and after study. Emerg Med Australas. 2015;27:232–8. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucca JM, Ramesh M, Narahari GM, Minaz N. Impact of clinical pharmacist interventions on the cost of drug therapy in intensive care units of a tertiary care teaching hospital. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2012;3:242–7. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.99422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabry NA, Farid SF. The role of clinical pharmacists as perceived by Egyptian physicians. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22:354–9. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calvert RT. Clinical pharmacy – A hospital perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;47:231–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00845.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Interviews main questions