Abstract

Vibrio cholerae is the agent of cholera, a potentially lethal diarrheal disease that remains a significant threat to populations in developing nations. The infant rabbit model of cholera is the only non-surgical small animal model system that closely mimics human cholera. Following oro-gastric inoculation, V. cholerae colonizes the intestines of infant rabbits, and the animals develop severe cholera-like diarrhea. In this unit, we provide a detailed description of the preparation of the V. cholerae inoculum, the inoculation process and the collection and processing of tissue samples. This infection model is useful for studies of V. cholerae factors and mechanisms that promote its intestinal colonization and enterotoxicity, as well as the host response to infection. The infant rabbit model of cholera enables investigations that will further our understanding of the pathophysiology of cholera and provides a platform for testing new therapeutics.

Keywords: Vibrio cholerae, cholera, enteric disease, animal infection model, infant rabbits

INTRODUCTION

Vibrio cholerae is the cause of cholera, a life-threatening diarrheal disease that remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in many parts of the developing world today. Humans become infected by ingestion of food or water contaminated with this gram-negative, curved, rod-shaped bacterium. After passage through the stomach, where the low pH milieu is a strong barrier to infection (Kaper et al., 1995), the non-invasive pathogen predominantly colonizes the small intestine. The bundle-forming toxin coregulated pilus (TCP) is V. cholerae’s chief colonization factor (Taylor et al., 1987), but many other gene products also facilitate the pathogen’s growth in the host intestine (Ritchie and Waldor, 2009). V. cholerae secretes cholera toxin (CT) in the intestine, and the action of this A-B5 type toxin causes the secretory diarrhea characteristic of cholera, primarily by stimulating chloride release from enterocytes into the intestinal lumen (Sears and Kaper, 1996). CT also induces exocytosis of mucins from goblet cells (Leitch, 1988), likely giving cholera stool its characteristic “rice water” appearance. Several animal model systems have been used to study cholera, however, most of them have important limitations. For example, V. cholerae colonizes the intestines of suckling mice after orogastric infection, but mice do not display pronounced diarrhea akin to human cholera. Ligated rabbit loops can been used to study intestinal secretion elicited by V. cholerae, but this model requires fairly complex surgery and bypasses the normal route of infection (De, 1959; De and Chatterje, 1953). It is therefore not appropriate for study of intestinal colonization factors. Recently, oro-gastric infection of infant rabbits has been found to lead to a disease that closely resembles severe human cholera (Ritchie et al., 2010). Infant rabbits are readily colonized in a TCP-dependent fashion by V. cholerae and develop CT-dependent lethal secretory diarrhea.

In this unit, we provide a detailed description of how to infect infant rabbits with V. cholerae and how to determine the bacterial burden within the gastrointestinal tract. We describe: i) how the inoculum is prepared (Basic Protocol 1), ii) how to infect 2-3 day old New Zealand white rabbits (Basic Protocol 2), iii) a safe and humane way to sacrifice infected rabbits (Basic Protocol 3), and iv) a way to remove and dissect infected tissues (Basic Protocol 4). Finally, the last protocol (Basic Protocol 5) gives instructions for processing the samples and determining the number of V. cholerae present. While this protocol details infant rabbit infection with V. cholerae, the same basic techniques can be used to study other diarrheal pathogens including Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Ritchie et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2013) and pathogenic E. coli including Shiga-toxin producing E. coli (Ritchie et al., 2003; Ritchie and Waldor, 2005; Munera et al., 2014).

CAUTION: Vibrio cholerae is a Biosafety Level 2 (BSL-2) pathogen. Follow all appropriate guidelines and regulations for the use and handling of pathogenic microorganisms. See UNIT 1A.1 and other pertinent resources (APPENDIX 1B) for more information.

CAUTION: This experiment requires Animal Biosafety Level 2 (ABSL-2) conditions. Follow all appropriate guidelines for the use and handling of infected animals. See UNIT 1A.1 and other pertinent resources (APPENDIX 1B) for more information. Protocols using live animals must first be reviewed and approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) or must conform to governmental regulations regarding the care and use of laboratory animals.

BASIC PROTOCOL 1

PREPARATION OF INFECTIOUS INOCULUM

This protocol describes the growth conditions and procedures used to prepare V. cholerae for oro-gastric inoculation into infant rabbits. After a starter culture is grown from a single, fresh bacterial colony to the correct density, the bacterial growth medium is removed and cells are resuspended in a buffer, which helps to neutralize the gastric pH.

Materials

Vibrio cholerae strains of interest with selectable marker (e.g., chromosomal streptomycin resistance)

LB-agar culture plate with appropriate selective agent (e.g., 200 ug/mL streptomycin)

LB medium with appropriate selective agent (e.g., 200 ug/mL streptomycin)

300 mM NaHCO3 solution, pH 9.0, sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 um filter

Culture tube, sterile

Incubator, 37 °C

Toothpicks, sterile

Shaking incubator, 30 °C or 37 °C

Erlenmeyer flask, sterile

50 mL centrifugation tube, sterile

Centrifuge with appropriate rotor for centrifugation tube, room temperature

Spectrophotometer, 600 nm

Cuvette

Eppendorf tubes, sterile

Prepare a fresh culture plate with the Vibrio cholerae strain(s) of interest by streaking from frozen glycerol stocks on a selective LB-agar plate and incubate the plate over night at 37 °C.

-

Pick a single colony with a sterile toothpick and use it to inoculate a 5 mL culture in selective LB medium. Grow in culture tubes over night at 30 °C or 37 °C with aeration to stationary phase.

Classical V. cholerae strains (e.g., O395) should be grown at 30 °C to induce expression of virulence factors, while El Tor strains (e.g., C6706 or N16961) can be grown at 30 °C or 37 °C.

-

Dilute over night culture 1:100 in 20 mL selective LB medium in an Erlenmeyer flask and grow for 3 h at 30 °C or 37 °C, respectively, with aeration into late exponential phase.

The volume of this culture should be sufficient to infect at least 10 rabbits with a standard infective dose of 109 CFU. Adjust the volume of this culture if more animals will be infected or if the infectious dose will be increased.

Transfer the culture to the centrifugation tube and pellet the bacterial cells by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 15 min at room temperature.

Discard the supernatant and resuspend the bacteria in 5 mL NaHCO3 solution.

Take a 100 uL aliquot, mix it with 900 uL NaHCO3 solution in a cuvette and measure the optical density in a spectrophotometer at 600 nm.

-

Adjust the concentration of bacteria in the inoculum to an OD600 of 1.4 with NaHCO3 solution; this corresponds to ~2×109 CFU/mL and an infectious dose of 109 CFU per rabbit.

500 uL of the inoculum will be used per rabbit infection (Basic Protocol 2). 104 to 1010 bacteria can used as inoculum (ID50 ~104). Typically an inoculum of 109 bacteria yields reliable results.

-

Transfer a 200 uL aliquot of the inoculum to an eppendorf tube for CFU determination (Basic Protocol 5).

Bacteria should not be left in NaHCO3 solution longer than necessary and both CFU determination as well as rabbit infection should be performed as soon as possible. However, the bacteria are stable for at least 1 hour at room temperature. Do not store V. cholerae on ice as the bacterium is sensitive to cold.

BASIC PROTOCOL 2

ORO-GASTRIC INFECTION OF INFANT RABBITS

This protocol describes the inoculation of 2-3 day old infant rabbits via the oro-gastric route, which resembles the natural infection route and does not require complex surgical procedures. After neutralization of the stomach acid with a histamine H2-receptor antagonist that inhibits production of stomach acid, various V. cholerae doses can be used for the infection. A standard infectious dose of 109 CFU results in colonization and causes cholera like symptoms of profuse diarrhea (and ultimately death) in virtually all animals within one day post inoculation. The fast progression of the disease coupled with heterogeneity in the susceptibility within and between rabbit litters requires careful monitoring of the animals health status post inoculation.

Materials

New Zealand white rabbit adult mother with 2-3 day old litter (e.g. from Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA)

70 % (v/v) ethanol in spray bottle

25 mg/mL Zantac (ranitidine hydrochloride), injection grade, USP

Sterile water for injection, USP (preservative-free)

Infectious inoculum (Basic Protocol 1)

70 % (v/v) ethanol

Water, sterile

Permanent marker with soft tip

Cardboard animal transfer boxes

Balance

Disposable exam gloves

Eppendorf tubes, sterile

1 mL syringe, sterile

30 G × ½ (0.3 mm × 13 mm) hypodermic needle, sterile

Size 4 French peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) with flexible tip (Arrow International, Reading, PA), sterile, with a permanent marker mark ~4 cm behind its tip

10 mL syringe, sterile

Sterilize the working area by spraying it with 70 % (v/v) ethanol, remove the nesting box from the mother’s cage and transfer it to the working area out of the mother’s sight.

-

Count the number of infant rabbits in the litter, remove each kit from the nesting box, mark it with permanent marker (e.g., by marking either the head, the mid back, the tail, the left and right ear, etc.), examine their health, put it temporarily in an empty cardboard animal transfer box and record its weight.

Do not touch the animals with bare hands and change gloves between each litter if kits from more than one doe will be infected! Paint large, distinctive areas of the animal’s body to mark them because the marker comes off easily. Healthy infant rabbits should be active, warm, clean and fed. Sometimes solid stool pellets stick to their fur, which is normal and of no concern, but liquid or semi-solid stool suggests the rabbit has gastro-intestinal (GI) infection and should be excluded from the experiment. The feeding status can be estimated by examining the stomach area. Well-fed kits have a pronounced, pear-shaped body and show a ‘milk-spot’ (i.e., the milk filled stomach that is visible as a lighter region through the skin). Note that the size of individual kits can vary strongly within and between litters (30 g – 120 g).

Dilute the Zantac stock to a final concentration of 2 ug/uL with sterile, injection-grade water in a sterile eppendorf tube before use.

Treat the kits with Zantac by intraperitoneal injection (Fig. 1A). Inject 2 ug Zantac per gram rabbit body weight using a 1 mL syringe with a 30 G × ½ hypodermic needle and press a finger on the injection site directly after injection to prevent reflux of liquid. Leave the kits in the nesting box in their mother’s cage for 3 h to allow time for the drug to neutralize the stomach acid.

Sterilize the working area by spraying it with 70 % (v/v) ethanol, remove the nesting box from the mother’s cage and transfer it to the working area out of the mother’s sight.

Attach the catheter to a 1 mL syringe and fill it with 500 uL of the inoculum. Remove air bubbles from catheter and syringe.

-

Hold the rabbit so that its left and right forelegs are immobilized and its head movement is restricted while the rest of its body can move freely (Fig. 1B).

A good hold is critically important for a successful inoculation! If the hold is too strong and immobilizing, the animal will not swallow the catheter. If the hold is too loose, the animal will free itself during the inoculation.

-

Carefully insert the catheter in the rabbit’s mouth and through the esophagus until about 4 cm (where the catheter is marked with permanent marker), when the stomach will be reached. Inoculate the kit with 500 ul of the inoculum and place the animal back in the nesting box.

How deep the catheter has to be inserted depends on the size of the kit, however ~4 cm is an average that reaches the stomach for most rabbit sizes. Do not use strong pressure while inserting the catheter and if resistance is felt, it is best to pull the catheter back a few millimeters before inserting it further. Have a second person help you to push the piston of the syringe for inoculation or hold the syringe in the same hand that guides the catheter and push the piston against the table.

Check the catheter for blood, which indicates the animal was injured during the gavage. If blood is found on the catheter the animal should be sacrificed (Basic Protocol 3).

Fill the catheter with fresh inoculum culture and proceed with the next animal. The same catheter can be used for all animals within a litter that are to be infected with the same inoculum.

After all kits within a litter have been infected, place the nesting box back into the mother’s cage to allow them to be fed ad libitum.

Clean the catheter by using a 10 mL syringe to flush it several times with water followed by 70 % (v/v) ethanol. Use an empty, sterile 10 mL syringe to blow out remaining liquid with air. The catheter can be used immediately for another litter/inoculum or stored sterilely until the next experiment.

-

Monitor the infected rabbits regularly for disease progression and sacrifice them at the planned end point of the study (Basic Protocol 3).

Cholera is a rapidly progressing disease and the time between visible onset of diarrhea to death can occur within a few hours. There is also substantial intra- and inter-litter variability in disease progression. Using a standard inoculum of 109 CFU V. cholerae per animal, the animals should be checked 12 h post-infection and then at hourly intervals. Typically, the first symptom that indicates the onset of cholera is the secretion of semi-solid/mucoid pellets of yellow-brown stool which becomes progressively more liquid and colorless until is resembles cecal fluid (see below). At the mid stage of the disease the animals become less active, have grayish skin color and a wet belly and hind legs. At the end stage of the disease the infected kits are lethargic and stop excreting stool due to severe dehydration. The animals should be euthanized at or before this last stage. While the kits normally nestle in the same spot, very sick animals separate from their littermates just before they die and should be euthanized without delay.

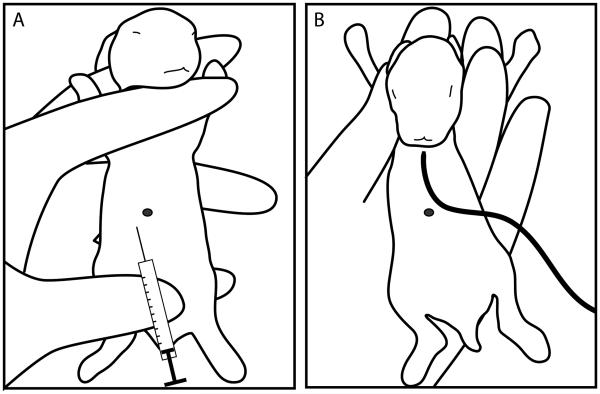

Figure 1. Hand positions for intraperitoneal injection and gavage of infant rabbits.

(A) For intraperitoneal injection of infant rabbits with Zantac, the forelegs and hind legs are immobilized and the abdomen is stretched as shown. The needle should be inserted slightly to the left and below the navel mark (black dot). (B) For insertion of the orogastric catheter into the mouth of the infant rabbit, the left and right forelegs are immobilized with the thumb and between the middle and ring finger, respectively. The index finger can be used restrict head movement. Immobilizing the lower body makes it more difficult to insert the catheter and should be avoided. The black line represents the catheter used for gavage.

BASIC PROTOCOL 3

EUTHANIZATION OF INFECTED INFANT RABBITS

This protocol describes a pain-free, safe and humane way to sacrifice infant rabbits. The animals are killed by long exposure to anesthetics that - apart from anesthetizing the animal - stops the heartbeat and breathing. After confirming that the animal’s reflexes have ceased, death is ensured by a lethal injection of potassium chloride into the heart before necropsy is started.

Materials

Isoflurane, USP

2 M KCl, injection grade, USP

Fume hood

1 L beaker or metal container with airtight lid

Metal grid that inserts into the container and covers the surface completely

Gauze

Forceps

3 mL syringe

Work under a fume hood while handling isoflurane.

-

Fill the bottom of the beaker or metal container with gauze, cover the gauze with the metal grid and wet the gauze with 6 mL isoflurane. Close the lid and let equilibrate for 10 min.

The metal grid serves to prevent direct exposure of animal body parts to isoflurane, which is painful.

-

Carefully transfer one animal into the container, close the lid and euthanize the animal with the isoflurane fume. The animal’s heart should stop beating after 2 min exposure.

If infected rabbits are at the end stage of the disease, longer exposure times (up to 10 min) can be required.

Take the animal out of the container and check for reflexes by pinching the hind paw with a pair of forceps.

-

If no reaction occurs, ensure death by intracardiac injection of 2.5 ml KCL (2 M).

To find the heart, insert the syringe caudal of the sternum and push upwards (cephalic) towards the heart in a flat angle for about 1 cm to 2 cm while applying light underpressure to the syringe. Once the heart is punctured a clearly visible amount of blood will enter the syringe.

Wait for about 2 min before starting the necropsy (Basic Protocol 4). Sacrifice and dissect one animal at a time. Replenish the isoflurane if there has been a long delay between sacrificing animals.

BASIC PROTOCOL 4

NECROPSY, DISSECTION OF THE GUT AND HARVESTING TISSUE

This protocol describes procedures for harvesting sections of the gastrointestinal tract. After opening the peritoneal cavity, the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum and colon are removed, cecal fluid is aspirated and the intestinal loops are disentangled. Cholera is a disease of the small intestine and bacterial loads are typically highest in the distal ileum. It can however be helpful to sample other section of the gastro-intestinal tract, especially the cecal fluid. This fluid contains high numbers of in vivo adapted V. cholerae with relatively little contamination from eukaryotic cells and can serve as a source of bacteria for downstream applications like transcriptomic analysis (Mandlik et al., 2011).

Materials

PBS, sterile

Beaker with 70 % (v/v) ethanol

Beaker with water

1.5 mL screw cap microvials, sterile

3.2-mm stainless steel tissue disruption beads (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK), sterile

Dissection board (cork, Styrofoam or plastic)

Medium dissection scissors

Medium tissue forceps

Small surgical scissors

Small angled forceps

1 mL syringe, sterile

26 G × 5/8 (0.45 mm × 16 mm) hypodermic needle

Body disposal bag

Fill one screw cap microvial per planned gut section with 900 uL PBS and two metal tissue disruption beads and note the final weight of the tube.

Disinfect all dissection instruments by placing them in the ethanol filled beaker. After a short incubation time (about 5 min), take out the instruments and let them dry by air.

Grab the navel mark with the tissue forceps and make a small incision through the skin and peritoneal wall with the dissection scissors (Fig. 2A).

Starting from this middle position, open the peritoneal cavity by cutting towards the upper left, upper right and lower left side of the animal to expose the intestinal tissue (Fig. 2B).

-

Gently pull the intestines out of the peritoneal cavity and detach by making a single cut at the top where the duodenum joins the stomach (Fig. 2C) and where the colon exits the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 2D). Detach the gut by severing the remaining connections of connective tissue and transfer the entire tissue to a clean dissection board. Place the carcass in a body disposal bag and dispose appropriately.

The final cuts that detach the gut tissue will also lead to considerable bleeding and makes working in the peritoneal cavity difficult.

Wash the gut tissue with PBS and keep the tissue moist during the dissection.

-

Harvest the cecal fluid by puncturing the cecum with 26 G hypodermic needle attached to a 1 mL syringe (Fig. 3).

The amount of cecal content varies with disease progression. In uninfected animals very little to no cecal fluid can be harvested (<10 uL), while the cecal fluid content increases gradually to up to 1 mL and more (dependent on animal size) at the late stage of the disease. However, at the end stage of the disease the majority of cecal content has been excreted and very little fluid can be recovered.

-

Disentangle the gut and align it on the dissection board.

Find the beginning of the duodenum (Fig. 4A). The proximal small intestine can be easily identified by its milky white luminal content in contrast to the brown content of the distal small intestine and the fecal pellet filled (uninfected or early stage of the disease) or clear (at the late stage of the disease) colon.

Start separating the intestinal loops by carefully tearing the loops apart using two small angled forceps or cutting the connective tissue that connects them with a pair of small surgical scissors (Fig. 4B).

Continue along the small intestine until the point where the cecum is attached to the small intestine (Fig. 4C) and separate the smooth tip of the cecum from the ileum with the scissors (Fig. 4D).

Isolate the remaining part of the small intestine and separate it from the colon until you reach the junction of ileum, cecum and colon (Fig. 4E).

Grab the tip of the cecum with the small angled forceps and separate the furrowed part of the cecum from the colon using scissors (Fig. 4F).

-

Find the distal end of the colon and disentangle it by cutting the connective tissue. Take special care around the middle section of the colon, which is embedded in fatty tissue (Fig. 4G,H).

It is difficult to distinguish colon and surrounding tissue especially at late infection stages when no fecal pellets are left in the colon.

-

Spread the gut on the dissection board and collect tissue samples (Fig. 4I).

A total of five tissue samples, each ~3-5 cm long, gives a fair representation of the bacterial load in each region. Three sections are taken in the small intestine (proximal, middle and distal), which is the main site of colonization (Ritchie et al., 2010), and one sample each is taken in the cecum and the colon.

Place each tissue sample in one pre-weighted screw cap microvial, calculate the sample weight and continue with tissue homogenization and CFU determination (Basic Protocol 5).

Place the remaining tissue in a body disposal bag and dispose appropriately. Wash the dissection instruments in a beaker with water before disinfecting them in the ethanol filled beaker. Clean the dissection board and disinfect with ethanol before dissecting the next animal.

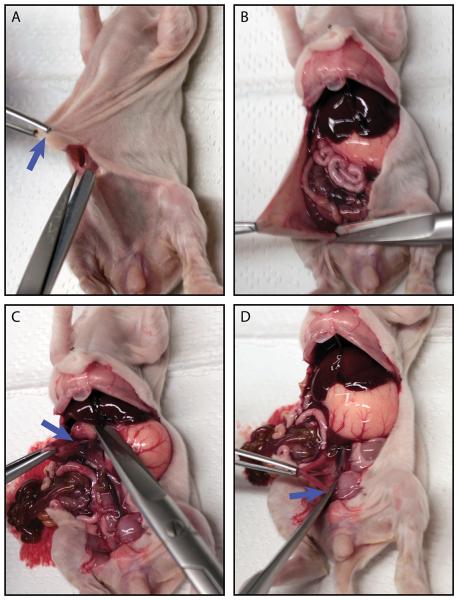

Figure 2. Dissection and removal of the intestinal tract from euthanized animals.

(A) The first incision through skin, subcutaneous tissue and peritoneum. The blue arrow indicates the navel. (B) Opening the peritoneal cavity with an ‘X’ shaped cut centered at the site of the first incision. (C) The blue arrow marks the site where the junction between stomach and duodenum should be cut. (D) The blue arrow marks the site where the colon exits the peritoneal cavity and should be cut.

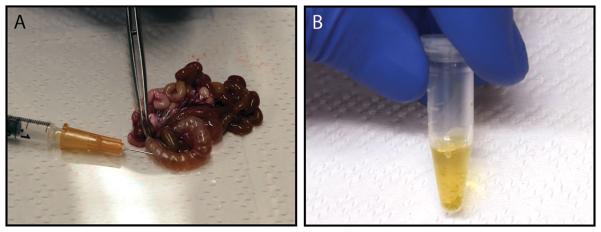

Figure 3. Aspiration of cecal fluid from the explanted intestine.

(A) The cecum can be punctured with a hypodermic needle to harvest its fluid. (B) Cecal content of 3-day-old, 80 g infant rabbit 16 h post infection with 109 CFU V. cholerae C6706.

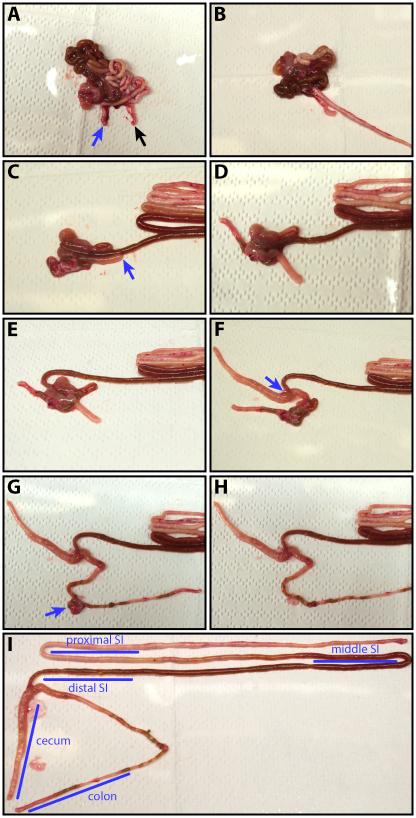

Figure 4. Dissection of the small intestine, cecum and large intestine.

(A) Indentifying the proximal duodenum and the distal colon. The blue arrow highlights the beginning of the small intestine with its characteristic milk-white luminal content. The black arrow indicates the colon. (B) Disentangling the small intestine. (C) Dissecting the distal ileum and separating it from the cecum. The blue arrow indicates the tip of the cecum. (D) Separating the tip section of the cecum from the ileum. (E) The ileum is dissected from the colon. (F) Isolation of the remaining cecum. The blue arrow indicates the junction between cecum, small and large intestine. (G) Dissection of the colon starting from its distal end. The blue arrow highlights the fatty tissue that is attached to the colon and difficult to remove. (H) The completely disentangled colon. (I) The intestine is spread out to allow sampling of reproducible sites with each region. The blue bars indicate samples that are typically taken and provide a good overview of the bacterial burden within the host.

BASIC PROTOCOL 5

TISSUE HOMOGENIZATION AND CFU DETERMINATION

While samples from the infected rabbits can be analyzed using a variety of techniques (Ritchie et al., 2010; Mandlik et al., 2011; Chao et al., 2013; Fu et al., 2013; Kamp et al., 2013; Pritchard et al., 2014; Abel et al., 2015), most experiments begin by quantifying the amount of V. cholerae colonization. Initially, intestinal tissue samples must be homogenized. This can be achieved by several different methods that vary by processing time, material investment and heat generation (too much heat is detrimental for V. cholerae). Bead-beater-type tissue homogenizers described in this protocol are fast and can be used to process multiple samples in parallel with acceptable heat generation, but require investing in the purchase of the equipment. In an alternative protocol (Alternative Protocol 5) we describe a method that does not require specialized hardware, but is time and labor intensive. After homogenization, serially diluted samples are plated on selective media and incubated until colony-forming units (CFUs) can be determined.

Materials

PBS, sterile

LB-agar culture plate with appropriate selective agent (e.g., 200 ug/mL streptomycin)

Thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose (TCBS) agar plates (e.g. from Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ)

Bead-beater-type tissue homogenizers (e.g., Mini-Beadbeater-16; Biospec, Bartlesville, OK)

Eppendorf tubes, sterile

Vortexer

-

Place the tissue samples in screw cap microvials filled with PBS and two metal tissue disruption beads in the bead-beater-type tissue homogenizers and thoroughly disrupt the tissue without letting the sample heat up too much.

Rabbit gut samples are typically homogenized after 2.5 min in a Mini-Beadbeater-16. If the tissue is not fully disrupted before it becomes too warm, allow it to cool down before starting another homogenization cycle.

Prepare seven eppendorf tubes with 900 uL PBS per collected tissue sample, cecal fluid sample and the three inoculum samples to make 1:10 dilution series.

-

Transfer 100 uL of the disrupted tissue to one of the prepared serial dilution tubes immediately after the homogenization and mix thoroughly.

The concentrated, disrupted tissue is toxic for V. cholerae and prolonged exposure results in low CFU counts. In addition, the disrupted tissue coagulates over time, which makes it difficult to work with.

Make a 1:10 dilution series by consecutively transferring 100 uL of the bacterial suspension to a fresh eppendorf tube filled with 900 uL of PBS. Mix thoroughly at each step.

-

Spot a 10 uL droplet of each dilution on top of a selective LB-agar culture plate, which is placed at a steep angle, and let the drop run down to spread the bacteria in a line across the plate.

Four drops can be easily placed next to each other on a standard 90 mm petri dish. If a total of eight dilutions are plated (1x concentrated homogenate, 7x 1:10 dilutions), two plates are required per sample.

Incubate over night at 37 °C.

-

Inspect colony morphology and verify suspect colonies by microscopy or plating on thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose (TCBS) agar plates.

Contaminating bacteria are rarely observed in gut homogenates of infant rabbits grown aerobically on LB agar, especially when a selective agent is added. However, the characteristic curved rod shape and the selective growth on TCBS agar, where V. cholerae produces large yellow colonies, allows easy identification of contaminations.

Calculate the CFU per volume or tissue weight, by multiplying the counted colonies with the correct dilution factor (accounting for the serial dilution and the fact that only 10 uL of the total volume have been plated) to obtain total CFU in the sample and divide this number by the measured sample weight (tissue samples) or total volume (inoculum, cecal fluid) to obtain CFU/g or CFU/ml, respectively.

ALTERNATE PROTOCOL 5

TISSUE HOMOGENIZATION WITH GLASS PLATES

This alternative method to homogenize gut tissue uses frosted microscope slides. While this method does not require specialized equipment and is very gentle, it is labor intensive and time consuming.

Materials

PBS, sterile

Standard microscope slides with frosted labeling area, sterile

90 mm bacteriological petri dish, sterile

Transfer 2 mL PBS to the petri dish.

Place the tissue sample on the frosted area of one slide and grind it with the frosted area of a second slide.

Use the PBS in the petri dish to wash homogenized sample of the slides.

Repeat until no solid tissue remains and continue with Basic Protocol 5 step 2.

COMMENTARY

Background Information

The first report of the use of infant rabbits as model hosts for V. cholerae dates to the 1890s (Metchnikoff, 1894). However, inoculation via the oro-gastric route did not reliably cause symptoms of the disease. This problem was solved when Dutta and Habbu injected the pathogen directly into the duodenum of infant rabbits (Dutta and Habbu, 1955). Although this procedure reliably causes cholera-like symptoms in infected animals, this model did not gain wide popularity, probably due to the required surgery (Finkelstein et al., 1992; Madden et al., 1981). Recently, Ritchie et al. revived the infant rabbit model of cholera by finding that a combination of pretreatment of animals with a histamine H2-receptor antagonist and applying the ora-gastric inoculum in a buffered solution substantially increases the success of V. cholerae colonizing the host intestine (Ritchie et al., 2010). This method, which we describe in this unit, causes development of watery-diarrhea in virtually all infected infant rabbits. Since then, this model has been successfully used to study the pathophysiology of V. cholerae infection in several different laboratories (Mandlik et al., 2011; Rui et al., 2010; Chao et al., 2013; Fu et al., 2013; Kamp et al., 2013; Pritchard et al., 2014; Abel et al., 2015).

In the last century various animal infection models have been tested to study cholera. These models include dogs (Sack et al., 1966), chinchillas (Blachman et al., 1974), guinea pigs (Freter, 1956), gnotobiotic/antibiotic treated adult mice (Miller et al., 1972; Nygren et al., 2009), zebrafish (Runft et al., 2014) and fruit flies (Blow et al., 2005). All of them have important limitations including requirements for extremely high infective doses, erratic infection rates, and/or requirements for difficult surgery. In addition, not all model animals develop cholera-like symptoms that are dependent on the known pathogenicity factors like TCP and CT. The most commonly used alternative animal models are the rabbit ligated ileal loop model (De, 1959; De and Chatterje, 1953) and the suckling mice model (Guentzel and Berry, 1974). Suckling mice can be readily colonized after oro-gastric inoculation with V. cholerae and have been used to study this process, but infected animals manifest little to no overt diarrhea and thus have limited value for studying factors underlying cholera physiology. In contrast, infected adult rabbits in the rabbit ligated ileal loop model have marked fluid secretion into the ligated loops, but in this closed system the pathogen is introduced by a non-physiological route. Furthermore, this surgical model requires specialized equipment and training, and the closed nature of a ligated ileal loop lacks several important aspects of GI tract physiology, e.g. peristalsis. Taken together, so far the infant rabbit model of cholera is the only small animal model that enables investigation of the normal V. cholerae colonization process as well as enterotoxicity.

Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting

The age of the rabbits is critical for this model because there is a relatively short period of time when the infant rabbits are susceptible to V. cholerae infection. Furthermore, very similar aged rabbits should be used to compare results from different litters. V. cholerae starter cultures should be inoculated with a freshly grown single colony and grown under the right conditions to the correct growth phase. Occasionally the adult female rejects her litter and fails to continue nursing her kits. This can be avoided by minimizing stress of the animal and only touching the kits with gloved hands. When working with different litters, it is essential to change gloves in-between as the adult may reject or even attack her kits due to the foreign smell. It is possible to ‘encourage’ feeding by placing the adult on the nest box, but if this fails and the adult neglects the kits for more than 48 h (detected by absence of weight gain), the experiment should be aborted and the kits should be euthanized. New Zealand white rabbits are outbred, and therefore, significant variability between litters is routine. Also kit size and feeding success varies within the litter. Together, this variability results in different kinetics of disease progression and careful monitoring is required post-infection. In addition, all experiments should be repeated with sufficient animals from multiple litters to correct for host differences. During the infection process it is critical to maintain a correct hold of the animal and insert the catheter with minimal pressure to avoid injuring the kit. To obtain CFU counts that accurately reflect the bacterial loads in vivo, it is important to limit the amount of time between euthanasia, dissection, homogenization and finally CFU plating. Note that V. cholerae is sensitive to temperatures outside a very limited range, which makes it impossible to store samples at low temperatures that would temporarily inhibit growth. Due to the same reasons, it is essential to avoid heating the tissue samples during their homogenization. Finally, homogenized samples should be diluted immediately in PBS as the concentrated homogenates coagulate, making it difficult to work with the samples, and prolonged exposure to the concentrated homogenates reduces V. cholerae recovery.

Anticipated Results

Directly after infection, animals should not display any symptoms and should be accepted and fed (usually once a day) by their co-housed mothers. Normally, the majority of the inoculated V. cholerae will not survive the infection process. It has recently been shown that from a dose of 109 CFU only ~105 V. cholerae survive (Abel et al., 2015). Although V. cholerae will initially spread to all sites of the GI tract within the first few hours after inoculation, the majority of organisms are only able to persist in the distal SI and bacterial numbers temporarily decrease at other sites of the gut. Accompanied by the onset of diarrhea, which manifests as excretion of semi-solid fecal particles, an increase in the bacterial burden is observed and the pathogen migrates from the distal SI to re-colonize the entire gut. During the progression of the disease, when diarrhea progresses from mild to severe, watery diarrhea, it is anticipated that the bacterial burden will increase to about 108-10 CFU/g tissue, with the lowest burden in the proximal SI and the highest in the distal SI. At this late stage of the disease, it is expected that capillaries are congested, heterophiles (the rabbit equivalent of neutrophils) accumulate in the lamina propria and mucins are excreted (Ritchie et al., 2010). Prolonged diarrhea leads to potentially fatal dehydration.

Time Considerations

The narrow window of infant rabbit susceptibility to cholera (less than 5 days after birth for optimal results) and the rapid growth rate of V. cholerae in LB medium dictate the timing of infection studies. An experiment is entirely dependent on the delivery date of infant rabbits. When rabbits become available, a starter culture of V. cholerae should be inoculated 24 hours prior to infection and subsequently diluted to prepare the inoculum 3 hours before infection. Although disease progression is heterogeneous, rabbits rarely develop symptoms within the first 10 hours of infection. Consequently, infections should be performed in the evening so that onset of disease symptoms can be monitored during working hours on the following day. To minimize the time between tissue extraction and CFU determination, it is advisable to prepare, label and weigh all required reagents, tubes and plates before the day of the dissection (tubes for homogenization and dilution series, agar plates). Colonies for CFU counting will already appear after several hours of incubation, but typically over night incubation is advisable. The plates can be stored several weeks at 4 °C before counting, as colony size does not increase at this temperature.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank Troy Hubbard and Pia Abel zur Wiesch for critical reading and helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Swiss National Fund (www.snf.ch) grant P300P3_155287/1 (S.A.), NIH grant R37 AI–042347 (M.K.W.) and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (M.K.W.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript, and the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abel S, Abel zur Wiesch P, Chang H-H, Davis BM, Lipsitch M, Waldor MK. Sequence tag-based analysis of microbial population dynamics. Nat Meth. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3253. advance online publication. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blachman U, Goss SJ, Pickett MJ. Experimental cholera in the chinchilla. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1974;129:376–384. doi: 10.1093/infdis/129.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow NS, Salomon RN, Garrity K, Reveillaud I, Kopin A, Jackson FR, Watnick PI. Vibrio cholerae infection of Drosophila melanogaster mimics the human disease cholera. PLoS pathogens. 2005;1:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao MC, Pritchard JR, Zhang YJ, Rubin EJ, Livny J, Davis BM, Waldor MK. High-resolution definition of the Vibrio cholerae essential gene set with hidden Markov model-based analyses of transposon-insertion sequencing data. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:9033–9048. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De SN. Enterotoxicity of bacteria-free culture-filtrate of Vibrio cholerae. Nature. 1959;183:1533–1534. doi: 10.1038/1831533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De SN, Chatterje DN. An experimental study of the mechanism of action of Vibriod cholerae on the intestinal mucous membrane. The Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology. 1953;66:559–562. doi: 10.1002/path.1700660228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta NK, Habbu MK. Experimental cholera in infant rabbits: a method for chemotherapeutic investigation. British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 1955;10:153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1955.tb00074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein RA, Boesman-Finkelstein M, Chang Y, Häse CC. Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/protease, colonial variation, virulence, and detachment. Infection and Immunity. 1992;60:472–478. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.472-478.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freter R. Experimental enteric Shigella and Vibrio infections in mice and guinea pigs. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1956;104:411–418. doi: 10.1084/jem.104.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. Tn-Seq analysis of Vibrio cholerae intestinal colonization reveals a role for T6SS-mediated antibacterial activity in the host. Cell Host & Microbe. 2013;14:652–663. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guentzel MN, Berry LJ. Protection of suckling mice from experimental cholera by maternal immunization: comparison of the efficacy of whole-cell, ribosomal-derived, and enterotoxin immunogens. Infection and Immunity. 1974;10:167–172. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.1.167-172.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp HD, Patimalla-Dipali B, Lazinski DW, Wallace-Gadsden F, Camilli A. Gene fitness landscapes of Vibrio cholerae at important stages of its life cycle. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9:e1003800. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper JB, Morris JG, Jr, Levine MM. Cholera. Clinical microbiology reviews. 1995;8:48–86. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch GJ. Cholera enterotoxin-induced mucus secretion and increase in the mucus blanket of the rabbit ileum in vivo. Infection and Immunity. 1988;56:2871–2875. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.11.2871-2875.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden JM, Nematollahi WP, Hill WE, McCardell BA, Twedt RM. Virulence of three clinical isolates of Vibrio cholerae non-O-1 serogroup in experimental enteric infections in rabbits. Infection and Immunity. 1981;33:616–619. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.2.616-619.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandlik A, Livny J, Robins WP, Ritchie JM, Mekalanos JJ, Waldor MK. RNA-Seq-based monitoring of infection-linked changes in Vibrio cholerae gene expression. Cell host & microbe. 2011;10:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metchnikoff E. Recherches sur le cholera et les vibrions. Receptivite des jeunes lapins pour le cholera intestinal. Ann. Inst. Pasteur. 1894;8:557. [Google Scholar]

- Miller CE, Wong KH, Feeley JC, Forlines ME. Immunological conversion of Vibrio chorlerae in gnotobiotic mice. Infection and Immunity. 1972;6:739–742. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.5.739-742.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munera D, Ritchie JM, Hatzios SK, Bronson R, Fang G, Schadt EE, Davis BM, Waldor MK. Autotransporters but not pAA are critical for rabbit colonization by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4. Nature Communications. 2014;5:3080. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren E, Li B-L, Holmgren J, Attridge SR. Establishment of an adult mouse model for direct evaluation of the efficacy of vaccines against Vibrio cholerae. Infection and Immunity. 2009;77:3475–3484. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01197-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JR, Chao MC, Abel S, Davis BM, Baranowski C, Zhang YJ, Rubin EJ, Waldor MK. ARTIST: High-Resolution Genome-Wide Assessment of Fitness Using Transposon-Insertion Sequencing. PLoS genetics. 2014;10:e1004782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie JM, Rui H, Bronson RT, Waldor MK. Back to the future: studying cholera pathogenesis using infant rabbits. mBio. 2010;1:e00047–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00047-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie JM, Rui H, Zhou X, Iida T, Kodoma T, Ito S, Davis BM, Bronson RT, Waldor MK. Inflammation and disintegration of intestinal villi in an experimental model for Vibrio parahaemolyticus-induced diarrhea. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8:e1002593. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie JM, Thorpe CM, Rogers AB, Waldor MK. Critical roles for stx2, eae, and tir in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli-induced diarrhea and intestinal inflammation in infant rabbits. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71:7129–7139. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7129-7139.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie JM, Waldor MK. The locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded effector proteins all promote enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli pathogenicity in infant rabbits. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73:1466–1474. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1466-1474.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie JM, Waldor MK. Vibrio cholerae interactions with the gastrointestinal tract: lessons from animal studies. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2009;337:37–59. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-01846-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui H, Ritchie JM, Bronson RT, Mekalanos JJ, Zhang Y, Waldor MK. Reactogenicity of live-attenuated Vibrio cholerae vaccines is dependent on flagellins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:4359–4364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915164107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runft DL, Mitchell KC, Abuaita BH, Allen JP, Bajer S, Ginsburg K, Neely MN, Withey JH. Zebrafish as a natural host model for Vibrio cholerae colonization and transmission. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2014;80:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03580-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack RB, Carpenter CC, Steenburg RW, Pierce NF. Experimental cholera. A canine model. Lancet. 1966;2:206–207. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)92484-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears CL, Kaper JB. Enteric bacterial toxins: mechanisms of action and linkage to intestinal secretion. Microbiological Reviews. 1996;60:167–215. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.167-215.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RK, Miller VL, Furlong DB, Mekalanos JJ. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84:2833–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Gewurz BE, Ritchie JM, Takasaki K, Greenfeld H, Kieff E, Davis BM, Waldor MK. A Vibrio parahaemolyticus T3SS effector mediates pathogenesis by independently enabling intestinal colonization and inhibiting TAK1 activation. Cell Reports. 2013;3:1690–1702. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]