Abstract

Primary health care is an evidence-based priority, but it is still inadequately supported in many countries. Ironically, on one hand, India is a popular destination for medical tourism due to the affordability of high quality of health care and, on the other hand, ill health and health care are the main reasons for becoming poor through medical poverty traps. Surprisingly, this is despite the fact that India was committed to 'Health for All by 2000’ in the past, and is committed to 'Universal Health Coverage’ by 2022! Clearly, these commitments are destined to fail unless something is done to improve the present state of affairs. This study argues for the need to develop primary care as a specialization in India as a remedial measure to reform its health care in order to truly commit to the commitments. Three critical issues for this specialization are discussed in this review: (1) The dynamic and distinct nature of primary care as opposed to other medical specializations, (2) the intersection of primary care and public health which can be facilitated by such a specialization, and (3) research in primary care including the development of screening and referral tools for early diagnosis of cancers, researches for evidence-based interventions via health programs, and primary care epidemiology. Despite the potential challenges and difficulties, India is a country in dire need for primary care specialization. India's experience in providing low-cost and high quality healthcare for medical tourism presages a more cost-effective and efficient primary care with due attention and specialization.

Keywords: India, primary, research, specialization

Introduction

The Alma-Ata declaration defined primary health care as, “essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in the spirit of self reliance and self-determination.”[1] Despite the idealistic proposition and enthusiasm that it gathered, inadequate funding, attention, and support remain a norm,[2] and in some countries, it has even deteriorated because of factors including, but not limited to- conflict, poor governance, structural adjustment, population growth, and disinvestment in health.[3]

It is worthwhile to emphasize that health care in general has progressed at a rapid pace in terms of both expertise and deliverables and has led to specializations and superspecializations, which seem to create an illusion that the health-care situation has improved in every respect, but this is far from the truth. Three critical issues haunt the current health-care situation as highlighted in the World Health Report 2007[4] – (1) health-care delivery inequality - both internationally and within nations; (2) inability to fittingly respond to the changing nature of health problems due to increased burden of noncommunicable diseases and consequences of factors such as unplanned urbanization, climate change, and social tensions; and (3) unpreparedness and vulnerability of the health systems’ adjustment to the rapid pace of change and transformation which include redefined roles of institutions, unregulated commercialization in health-care delivery, and politicized entitlement claims and rights of the patient. Among other reasons, lack of primary care accentuates the problems of the current health-care situation.

India, the second most populated country in the world, has a unique position with regard to health care. On one hand of the spectrum, the country provides a good quality of health care and specialization at a very affordable price making it one of the popular destinations for medical tourism and, on the other hand, the wide majority of Indians suffer from poor health. The country that is known for providing cost-effective high-quality health care, unfortunately, has only two health-care options for its natives- use the unregulated and often overpriced private health care and, if unaffordable, use the public health system, which is generally considered substandard. According to Balarajan et al., of the total health spending in India, more than three-fourths is private and the high out of pocket expense accounts for more than half of the Indian households falling into poverty![5] Previous studies suggest that a strong primary-care network with a strong public health has the potential to improve this situation and lead to a better health equity.[5]

This does not mean that India does not have a primary health-care system. On the contrary, India built its health system on the foundations of primary care as suggested by the Bhore Committee in 1946 and committed to the call for “Health For All by 2000 AD” in its National Health Policy, 1983,[6] almost as enthusiastically as it has committed to the “Universal Health Coverage by 2022,”recently.[7] Clearly, commitments similar to these are destined to fail unless something concrete is done to improve the present state of affairs in the primary care of India. Redefined role and responsibility of primary health care and strong commitment toward it- is the need of the hour to improve this situation and to achieve the Universal Health Coverage. This paper argues for the need to develop primary care as a specialization in India as one of the most important remedial measures to reform its health care. The primary care as a specialization should be developed to find plausible, effective, and pragmatic solutions for the poor health care at grassroot levels. We address four issues to emphasize the need and importance of primary care specialization: (1) Primary care specialization - the dynamic scope, (2) tapping the true potential of primary care, (3) scope and need for primary care research, and (4) primary care and public health.

Primary Care Specialization - The Dynamic Scope

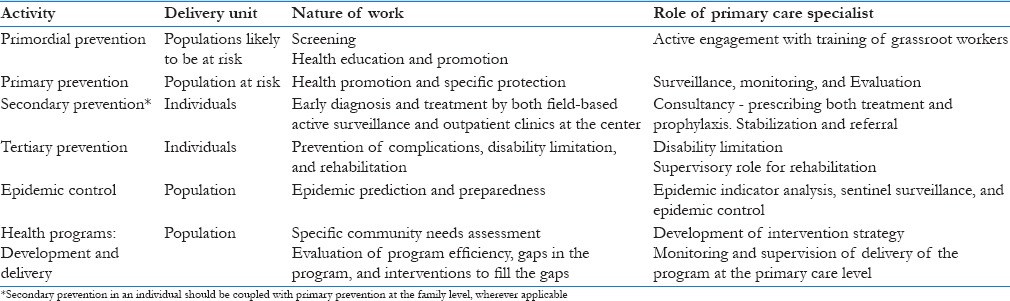

Primary care is the first point where the individual or the patients interact with the health system, which provides and delivers a first point contact, longitudinal, comprehensive, and person-centric care.[8] The four main features of primary care services are first-contact access for each new need, long-term person (not disease)-focused care, comprehensive care for most health needs, and coordinated care when it must be sought elsewhere.[8] Thus, primary care deals with a majority of the population and is expected to provide both primary and secondary level of prevention together with referral services. By the very definition and scope, primary care is a specialty whose practitioners should have the expertise of community needs assessment, making a community diagnosis, delivering a community-based treatment, addressing structural reasons for common illnesses and, at the same time, making early diagnosis and issuing prompt treatment to individuals like the rest of their colleagues working in the hospital, although the more complicated cases have to be referred [Table 1]. Although a comparison is unnecessary, the primary care specialization will cater to a larger burden of diseases and have a wider research area with regard to both population and range of diseases when compared to any other specializations in medicine. The discipline of family medicine and/or general practice is also included in the primary care specialization. Because of the lack of inputs from the primary level, most of the health programs in India fall short of their objectives to improve the widely prevalent problems of malnutrition, anemia, tuberculosis etc. In addition, through the gatekeeping role, primary care plays a principal role in the medical referral system leading to a decreased burden at the overburdened higher centers [Table 1].

Table 1.

A summary of the key areas of primary care specialization

Tapping the True Potential of Primary Care

Although primary care looks like an idealistic philosophy, in reality, it is a realistic proposition. It is an evidence-based priority as health-care systems configured around primary care produce healthier populations at a lower cost.[9] There are evidence from different countries around the world to demonstrate that primary care improves health as (1) health status is better in areas with more primary care physicians, (2) people who receive care from primary care physicians are healthier, and (3) the characteristics of primary care are associated with better health.[10] The example of England is notable where an increase of just one primary care doctor per 10,000 populations is associated with a 6% decrease in mortality.[11] It is also important to note that contrary to popular perceptions, it has been seen that if services are organized with primary care forming the first level of care, better health results as opposed to systems predominated by specialists.[8,12] These primary care-based health-care systems have better quality of care, better population health and greater equity at a lower cost.[13,14] The primary care-based health-care model is indispensable for betterment of the grim public health situation in India. Although there are successful models and success stories of primary care around the world, harnessing its true potential in India is difficult without a primary care specialization. We argue in favor of primary care specializations to translate, adapt, and acclimatize the models according to India-specific health-care problems, especially catering to the following factors:

Addressing the unpopularity of primary care

Reforming the gatekeeping role of primary care

Confronting the epidemiological and demographic transition.

Addressing the unpopularity of primary care

The primary care among masses is unpopular and is only used as a last resort because of unaffordability or any other compulsion. Although there have been some improvements, the impression that the masses rightly have is that they are understaffed,[15] ill-equipped,[15] and have a poor infrastructure including location.[16] Furthermore, we believe that a primary care specialist will have the necessary knowledge to help counter the existing need–demand paradox that exists in public health in India.[17] The primary care specialist at his disposal would have the necessary training to undertake research in the different sectors that will determine and address the modifiable factors responsible for the low popularity and poor performance of primary health care, besides making an economic case for the primary care.

Reforming the gatekeeping role of primary care

In the resource-limited settings, gatekeepers ensure equity and reduce self-referrals, improving the efficiency of doctors at the secondary care[9] and saving the patients from overtreatment. Although the role of gatekeeping has been seen as a generalist, it requires a profound knowledge of guidelines and referral mechanisms of the country. The Indian primary care's gatekeeping role is very limited and has not been considered a priority; although, the judicious use of gatekeeping is considered to provide high-quality and cost-effective health care.[10,18,19] The gatekeeping role should be introduced in the Indian settings because the higher centers have a huge patient load, mostly of the patients who require primary care-based treatment, or have complications which could be prevented at the primary care. Proper gatekeeping can reduce this enormous load at higher centers and, in turn, will make them more accountable and transparent, besides protecting the patients against overtreatment and lowering the rate of transmission to and from the patient at higher centers. A specialized and skilled primary care practitioner can be an efficient gatekeeper as opposed to a nonspecialist because it requires a firm grounded medical knowledge of referrals and the legal laws pertaining to it.

Confronting the epidemiological and demographic transition

India is undergoing an epidemiological and demographic transition, the scale of which is incomparable to any country of the world due to its high population and diversity. A RAND policy brief highlights the ineffective preparedness to combat the residual burden of the communicable and poor nutrition-based diseases and rising burden of noncommunicable and lifestyle disease with the compounding factors of aging and other transitional changes in the country.[20] Diseases on both the ends of the spectrum, for example, undernutrition or obesity, can be best managed at the primary care. Neglecting these diseases only complicates the cases, increases the cost of treatment, and leads to a poorer prognosis when managed at a higher center. The efficient primary care specialist will confront these transitional diseases through primary prevention aggressively, starting with screening and going all the way to periodic monitoring of the different body systems. At present, the exact scale of the problem is not known, and only a community-based research will help us estimate the problem and formulate effective interventions, in the absence of which, the problem may compound to become a crisis.

Scope and Need for Primary Care Research

Primary care should be evidence-based and therefore researches in primary care are integral to this specialization. Even though primary care manages most of the illnesses in many countries, it has been poor in terms of research input and output.[21] Due to the absence of primary care specialists and inadequate attention to primary care in India, this area is still unexplored in researches. There are many high prevalence diseases in India like malnutrition and anemia, the causes of which are structurally embedded in the sociocultural lives of people and should not be reasoned or treated with clinical treatment alone. These structural causes are specific to diverse lifestyles and can only be researched and appropriately addressed at primary care levels. Integrated packages on interventions in mental illnesses, cancers, cardiovascular diseases, stroke, and diabetes with many other diseases are best implemented at primary health-care levels, especially in lower-income countries, with regard to health outcomes and cost-effectiveness.[22] Another important area that is in need of primary care-based research is the development of screening and referral tools for cancers and other diseases that are usually diagnosed very late, when their prognosis is very poor. The longitudinal care of primary care should be explored further to find symptom-based screening tools for early detection of cancers, especially with apparently mild symptoms such as headaches in brain tumors,[23] and epidemiology of patient safety incidents.[24]

Often, the health programs modify their interventions or ways of working to find solutions to the common problems of malnutrition, anemia, micronutrient deficiencies, and other public health problems with little improvements at the ground level. Randomized controlled evaluations of interventions that can work at a community level are still in their infancy and, therefore, vital questions remain unanswered. If a drug has to go through the various steps of randomized trials to prove its safety and effectiveness, does not the primary care working on a population level need any research to support the effectiveness of such a population-based intervention? Also, in the absence of prior research, is it ethical on the part of the government to continue spending the taxpayer's money on interventions that do not have enough credible evidence demonstrating community-based effectiveness? Further, the use of ineffective interventions in the hope that they will work wastes a lot of time, resources, and opportunity that should be used to find working solutions. In addition, it unnecessarily creates an atmosphere of doubt on the part of expected outcomes of public health and primary care-based interventions.

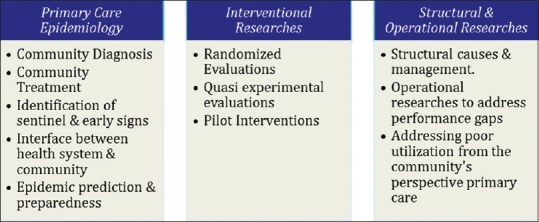

Another vital area of primary care research is primary care epidemiology, emphasized by experts in the 1970s[25,26] but never picked up the momentum that it deserved. Primary care epidemiology is defined as “application of the approach of clinical epidemiology to primary care practice,” with an added focus on community diagnosis and its use to modify the activities of the practice.[26] The discipline includes studies of the interface between primary care and the community/general population, primary and secondary (or tertiary) care, and different members of the primary health care team.[27] Primary care epidemiology should also include researches on drivers of health care utilization and determinants of health seeking behavior including the preferences for health-care providers whether allopathic or indigenous systems to further address their misconceptions, concerns, and beliefs in the public health system and specifically primary care. Primary care epidemiologists also need to rise to the challenges of engaging the public in their work so that they research with, rather than on the population.[28] A summary of the key research areas in primary care has been reproduced with permission of Faizi et al. in Figure 1.[29]

Figure 1.

A summary of key research areas in primary care

Primary Care and Public Health

The primary care as a specialization offers a better and more interactive collaboration with public health; the critical role of which has been emphasized in previous researches.[30] Community planning, defined as an organized process to design, implement, and evaluate a clinic- or community-based project to address the needs of a defined population,[31] would need inputs from public health for effective delivery. Public health models and tools for better accounting and management of primary care successfully used in the developed world like- Predisposing, Reinforcing, and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation and Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development,[32] Planned Approach to Community Health,[33] or Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships,[34] and others, need to be modified and adapted to work in the Indian primary care settings.

The intersection with public health would also be important for concept building and skill development in theories of behavioral change, concepts of communication and social marketing, and other vital areas for primary care-based health promotion activities. Development of community-based health indicators, determinants of health and diseases, and developing effective intervention are also the key areas of primary care that warrant contributions from public health. Thus, some of the key areas that the collaborations can address are:[16]

Biomedical issues – commonly chronic diseases and communicable disease control including immunizations

Behavioral issues – smoking cessation and other deaddictions, screening and other preventive activities

Socio-environmental issues – poverty, community development, and disaster response planning

Access to health care for underserved or vulnerable populations.

The collaboration between primary care and public health is a work in progress, and should be kept in mind to find effective solutions that may help identify and refine the exact nature of this collaboration during the very development of this specialization in the country.

Conclusion

We firmly believe that there is a dire need of primary care specialization in India because of its different and dynamic scope as compared with other specializations. Specialization is needed to tap the true potential of primary care, to cater to the enormous research potential in primary care, and to collaborate effectively with public health to improve the health-care situation of the country. Given the successful experience of cost-effective medical care that augurs well for medical tourism, India can take a lead in providing a cost effective primary care specialization model that can have far reaching health outcomes. Through better gatekeeping and referrals, a successful primary care specialists’ role may have a domino effect in favor of a true public health revolution in India. Evidence-based population/community intervention is not possible without a primary care specialization in India, and it raises pertinent questions on the continuation of interventions with poor/no research backing. We also believe that primary care specialization can address the critical problems of the current health-care situation.

That being said, we admit that there are some very big challenges to the development and adoption of primary care specialization. The first and foremost of which is getting the political, economic, and administrative commitment to the same, given the fact that India's health-care spending is among the lowest in the world and, surprisingly, was further reduced recently.[35] Apart from that, a stiff opposition is expected from traditional branches of specialization especially from the private sector, because it will lead to lesser number of patients who are their source of income. The other potential challenge is the uptake of this specialization among the medical graduates and its future scope of growth. If the scope consists of working at the primary health center alone, it is bound to fail as the primary health center already suffers from dearth of workers and high worker absenteeism.[36]

Further researches and policy briefs are needed to build momentum for the political commitment and to study the feasibility, solve these challenges, and make a case in favor of this specialization. The future scope of primary care specialists should be in the planning and programming sector depending on their potentials, performance, and standards. As far as the takers are concerned, a higher stipend and perks may be considered for the primary care doctors depending on their performance.

However big the challenges are, we have to find answers to these challenges, failing which our dismal state of public health will stay as it is or even get worse. Before a state of crisis erupts, we have to find a solution to the enormous public health challenges that lie ahead of the country and a cadre of primary care specialists can fulfill this in the most cost-effective fashion!

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Declaration of Alma Ata: International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September, 1978. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf .

- 2.De Maeseneer J, van Weel C, Egilman D, Mfenyana K, Kaufman A, Sewankambo N, et al. Funding for primary health care in developing countries. BMJ. 2008;336:518–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39496.444271.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhutta ZA, Belgaumi A, Abdur Rab M, Karrar Z, Khashaba M, Mouane N. Child health and survival in the Eastern Mediterranean region. BMJ. 2006;333:839–42. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38979.379641.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. The World Health Report 2008: Primary Health Care Now More than Ever. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV. Health care and equity in India. Lancet. 2011;377:505–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61894-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Health Policy 1983. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. New Delhi: Government of India; 1983. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. Available from: http://www.communityhealth.in/~commun26/wiki/images/6/64/Nhp_1983.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.High Level Expert Group Report on Universal Health Coverage for India; 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. Available from: http://www.planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/rep_uhc0812.pdf . [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oldham J, Richardson B, Dorling G, Howitt P. Primary Care – The Central Function and Main Focus. 2012. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. Available from: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/institute-of-global-health-innovation/public/Primary-care.pdf .

- 10.Starfield B. What is primary care? Lancet. 1994;344:1129–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulliford MC. Availability of primary care doctors and population health in England: Is there an association? J Public Health Med. 2002;24:252–4. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/24.4.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starfield B, Shi L, Grover A, Macinko J. The effects of specialist supply on populations' health: Assessing the evidence. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W5-97–W5-107. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W184–97. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2007;37:111–26. doi: 10.2190/3431-G6T7-37M8-P224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeravdekar R, Yeravdekar VR, Tutakne MA, Bhatia NP, Tambe M. Strengthening of primary health care: Key to deliver inclusive health care. Indian J Public Health. 2013;57:59–64. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.114982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyengar S, Dholakia RH. Access of the Rural Poor to Primary Healthcare in India. IIM Ahmedabad Working Paper 2011. 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. pp. 1–24. Available from: http://www.iimahd.ernet.in/assets/snippets/workingpaperpdf/3937368102011-05-03.pdf .

- 17.Sharma K, Zodpey S. Public health education in India: Need and demand paradox. Indian J Community Med. 2011;36:178–81. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.86516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forrest CB. Primary care in the United States: Primary care gatekeeping and referrals: Effective filter or failed experiment? BMJ. 2003;326:692–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7391.692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starfield B, Powe NR, Weiner JR, Stuart M, Steinwachs D, Scholle SH, et al. Costs vs quality in different types of primary care settings. JAMA. 1994;272:1903–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Policy and Health in Asia: Demographic and Epidemiologic Transitions. RAND. 1999. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. Available from: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_briefs/RB5036/RB5036.pdf .

- 21.Mant D, Del Mar C, Glasziou P, Knottnerus A, Wallace P, van Weel C. The state of primary-care research. Lancet. 2004;364:1004–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17027-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. Package of Essential Non-communicable Disease Interventions for Primary Health Care in Low-Resource Settings. Available from: http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/essential_ncd_interventions_lr_settings.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boiardi A, Salmaggi A, Eoli M, Lamperti E, Silvani A. Headache in brain tumours: A symptom to reappraise critically. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(Suppl 3):S143–7. doi: 10.1007/s10072-004-0274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dovey SM, Wallis KA. Incident reporting in primary care: Epidemiology or culture change? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:1001–3. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hart JT. The marriage of primary care and epidemiology: The Milroy lecture, 1974. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1974;8:299–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullan F. Community-oriented primary care: Epidemiology's role in the future of primary care. Public Health Rep. 1984;99:442–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannaford PC, Smith BH, Elliott AM. Primary care epidemiology: Its scope and purpose. Fam Pract. 2006;23:1–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watt G. William Pickles lecture. General practice and the epidemiology of health and disease in families. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:939–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faizi N, Khan MS, Hassan J. Primary healthcare research in India: The wide spectrum, the pressing need and the academicapathy. International Conference on Public Health: Issues, Challenges, Opportunities, Prevention, Awareness (Public Health: 2016) In: Roy S, Mishra GC, Nanda S, Jain A, editors. New Delhi: Krishi Sanskriti Publications; 2016. pp. 40–2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levesque J, Breton M, Senn N, Levesque P, Bergeron P, Roy DA. The interaction of public health and primary care: Functional roles and organizational models that bridge individual and population perspectives. Public Health Rev. 2013;35:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKenzie J, Pinger R, Kotecki J. An Introduction to Community Health. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2005. p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- 32.LGreen. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. Available from: http://www.lgreen.net/precede.htm .

- 33.LGreen.net. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. Available from: http://www.lgreen.net/patch.pdf .

- 34.National Association of County and City Health Officials. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. Available from: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/mapp/

- 35.Health Expenditure, Public (% of total health expenditure), World Bank. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 09]. Available from: http://www.data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PUBL .

- 36.Hammer J, Aiyar Y, Samji S. Understanding government failure in public health services. Econ Polit Wkly. 2007;42:4049–57. [Google Scholar]