Abstract

Tumor cell invasion and resistance to therapy are the most intractable biological characteristics of cancer and, therefore, the most challenging for current cancer research and treatment paradigms. Refractory cancers, including pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma, show an inextricable association between the highly invasive behavior of tumor cells and their resistance to chemotherapy, radiotherapy and targeted therapies. These aggressive properties of cancer share distinct cellular pathways that are connected to each other by several molecular hubs. There is increasing evidence to show that glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)‐3β is aberrantly activated in various cancer types and this has emerged as a potential therapeutic target. In many but not all cancer types, aberrant GSK3β sustains the survival, immortalization, proliferation and invasion of tumor cells, while also rendering them insensitive or resistant to chemotherapeutic agents and radiation. Here we review studies that describe associations between therapeutic stimuli/resistance and the induction of pro‐invasive phenotypes in various cancer types. Such cancers are largely responsive to treatment that targets GSK3β. This review focuses on the role of GSK3β as a molecular hub that connects pathways responsible for tumor invasion and resistance to therapy, thus highlighting its potential as a major cancer therapeutic target. We also discuss the putative involvement of GSK3β in determining tumor cell stemness that underpins both tumor invasion and therapy resistance, leading to intractable and refractory cancer with dismal patient outcomes.

Keywords: Cancer, GSK3β, invasion, therapeutic target, therapy resistance

One of the well‐recognized but still poorly understood characteristics of cancer is its ability to adapt and survive in a harsh microenvironment. Tumor cells survive the hypoxic and starved conditions by changing their morphological and biological properties and by interacting with tumor‐associated stromal components.1 Another striking characteristic of cancers is their ability to invade host organs and to resist therapeutic insults, thus limiting the success of curative tumor resection and leading to tumor metastasis and therapy failure. These pathological behaviors of cancer are associated with acquisition of the hallmark biological traits of cancer.2, 3, 4 Despite recent advances in cancer treatments, the existence of unresectable and recurrent cancers that share the persistent capacity for invasion, metastasis and therapy resistance remains a challenge for current medical therapies.5, 6 Although our knowledge of the molecular and biological mechanisms by which cancer evolves to the refractory stage is increasing,2 few strategies have been established to attenuate the ability of tumors to invade or to prevent the failure of therapy.

Modern options for cancer treatment consist of surgery, cytotoxic or cytostatic chemotherapeutics, radiation, molecular‐targeted and immunomodulating agents, and their multidisciplinary combination.7, 8 These treatments aim primarily to reduce tumor cell survival and proliferation, but not to eliminate invasive ability or resistance to therapy. Therefore, understanding the pathways by which cancer cells acquire both invasive and therapy‐resistant phenotypes is critical for the development of more efficient therapeutic strategies against refractory cancers and, therefore, improvements in patient survival. Apart from the known mediators of invasion and therapy resistance [reviewed in Alexander and Friedl9], one emerging candidate is glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)‐3β. This molecule has been extensively implicated in critical cell biology processes and has causal roles in common diseases including glucose intolerance, neurodegenerative disorders and cancer.10, 11, 12 Here we review previous studies that have reported on the association between therapeutic stimuli/resistance and induction of pro‐invasive phenotypes in various cancer types. Many of these cancers have proven to be responsive to experimental treatment which targets GSK3β. This review focuses on the role of GSK3β as a molecular hub that connects pathways responsible for tumor invasion and resistance to therapy, thus highlighting this kinase as a promising multipurpose cancer therapeutic target. It also discusses a putative role for GSK3β in sustaining the tumor cell “stemness” that is central to both tumor invasion and therapy resistance, thereby leading to intractable cancer and resulting in treatment failure.13, 14, 15

Invasion and therapy resistance co‐segregate in refractory cancer

High invasiveness and resistance to therapy are common biological and clinical characteristics of refractory cancer that represent major challenges for research and treatment. The mechanisms involved in tumor invasion include cell motility and migration, degradation of the extracellular matrix and interaction with stromal and inflammatory cells. These are orchestrated in a way that enables the tumor to invade the host organ and often beyond.3, 4 An early morphological and functional change for tumor cells of epithelial origin to acquire a proinvasive phenotype is epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), altering cell behavior to resemble a mesenchymal type.16, 17 The major modes by which cancers evade the effect of anti‐cancer drugs include intrinsic (or constitutive) resistance and acquired resistance. Constitutive resistance to therapy may be due to mutational activation of signaling for cell survival, cytoprotective alterations in the cell cycle and in DNA repair ability, differences in the efficiency of drug uptake and efflux by cancer cells, and insufficient drug delivery [reviewed in Alexander and Friedl9]. Acquired resistance to chemotherapeutic and molecular‐targeted agents involves distinct mechanisms, including genetic alterations to the drug targets, activation of surrogate prosurvival pathways, and interactions between tumor cells and components of the tumor environment [reviewed in Holohan et al.5, Ramos and Bentires‐Alj6 and Alexander and Friedl9]. Intra‐tumor heterogeneity emerges in many tumors and often underlies their resistance to therapeutic agents.18, 19

The processes of tumor invasion and therapy resistance and their underlying mechanisms are often investigated as independent pathological events in cancer. However, recent studies (shown in Table 1) have demonstrated that tumor cells acquire morphological and functional proinvasive phenotypes with the ability to migrate and invade following the development of resistance to anti‐cancer therapeutics (Suppl. References [SR] 1–24) (Data S1).(SR1–24) The therapeutic modalities included conventional chemotherapeutic agents(SR1–15), different types of radiation therapy(SR16–20) as well as bioactive compounds targeting epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).(SR21–24) These studies indicate the therapeutic insult and/or resistance elicits proinvasive phenotypes and evokes the invasive capability of tumor cells in a broad spectrum of cancer types, including breast, colorectal, pancreatic, ovarian and prostate cancers, as well as rare intractable tumors (e.g. glioblastoma and osteosarcoma). A large number of preclinical studies have demonstrated that all available cancer treatments, including surgery, facilitate metastatic tumor spread. Such treatment often results in therapeutic benefit, but occasionally also results in resistance, leading to the paradoxical concept of “treatment‐induced metastasis” [reviewed in Ebos20]. These experimental and preclinical studies suggest that the invasive behavior of cancer cells and their acquired resistance to therapy may not be separate pathological properties and could, instead, represent interconnected processes [reviewed in Alexander and Friedl9].

Table 1.

Representative previous studies showing interrelationship between therapeutic stimuli/resistance and pro‐invasive phenotype in cancer

| Tumor type | Therapeutic insults | Biological mechanism (Suppl. Reference number) | Therapeutic effect of GSK3β inhibition and underlying mechanism (Reference number) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Tamoxifen | EGFR pathway, enhanced tumor cell motility and invasion(SR1) | Suppression of invasion through dysregulation of actin‐reorganization via down‐regulation of WAVE268 |

| Tamoxifen | EMT induction with EGFR pathway‐dependent β‐catenin activation(SR2) | ||

| Adriamycin | Twist 1‐meditaed EMT induction and P‐gp up‐regulation(SR3) | ||

| Doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide alone or in combination | TNF‐α/NF‐κB‐mediated amplification of CXCL1 paracrine network between carcinoma, myeloid, and endothelial cells(SR4) | ||

| Colorectal cancer | Oxaliplatin | NF‐κB‐mediated EMT induction with enhanced cell migration and invasion(SR5) | Suppression of tumor cell survival and proliferation by inhibition of hTERT/telomerase and promoting p53‐dependent apoptosis28, 29, 30, 32, 33 and invasion by down‐regulation of WAVE2,68 and enhancing 5‐FU effect via PARP1‐dependent and AIF‐mediated necroptosis73 |

| Erlotinib | EMT induction(SR21) | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | Gemcitabine | EMT induction with activation of β‐catenin and c‐Met and acquisition of CSC phenotype(SR6) | Suppression of tumor cell survival and proliferation30 by inhibition of NF‐κB transcriptional activity,34, 35 synergistic with gemcitabine by restoration of Rb function60 and inhibition of TP53INP1‐mediated DNA repair,70 increase in radiosensitivity and suppression of invasion via FAK/Rac1/MMP‐2 and CXCR4/MMP‐2 pathways60, 67 |

| Gemcitabine | Acquisition of EMT and CSC phenotypes with activation of Notch pathway(SR7) | ||

| Gemcitabine, 5‐FU, cisplatin | Gene expression profile responsible for EMT phenotype(SR8) | ||

| Gemcitabine | NF‐κB‐mediated acquisition of EMT and CSC phenotypes(SR9) | ||

| γ‐irradiation | Tumor cell migration and invasion with enhanced MMP‐2 activity(SR16) | ||

| Erlotinib | EMT induction(SR21) | ||

| Ovarian cancer | Taxol, vincristine | Increased expression of twist(SR10) | Suppression of tumor cell proliferation by decrease in cyclin D1 expression39 |

| Paclitaxel | Acquisition of EMT and metastatic potential(SR11) | ||

| Cisplatin, taxol | Acquisition of EMT via endothelin A receptor‐mediated pathway(SR12) | ||

| Prostate cancer | Taxol, vincristine | Increased expression of twist(SR10) | Suppression of tumor cell survival and proliferation by eliminating TRAIL resistance, repressing AR activity,41, 42, 43, 44 and attenuation of metastasis by depleting CSC population78 |

| Docetaxel | Gene expression profile responsible for EMT phenotype(SR13) | ||

| Other epithelial cancer | |||

| Endometrial | Ionizing radiation | EMT induction with enhanced cell migration(SR17) | Suppression of tumor cell survival by interrupting ERK‐mediated prosurvival pathway40 |

| Bladder | Taxol, vincristine | Increased expression of twist(SR10) | Suppression of tumor cell survival and proliferation by inhibition of NF‐κB transcriptional activity45 |

| Tongue | Cisplatin | EMT induction and enhanced cell migration and invasion in association with increased BMI1 by down‐regulation of miR‐200b and miR‐15b(SR14) | Not shown |

| Nasopharyngeal | Taxol, vincristine | Increased expression of twist(SR10) | Not shown |

| Glioblastoma | Doxorubicin | Therapeutic effect and enhancement of doxorubicin effect by a new anti‐invasive small molecule (IB)(SR15) | Suppression of tumor cell survival and proliferation by restoring p53/p21 pathway and inhibition of c‐Myc, NF‐κB and abnormal glycolysis,31, 36 synergistic with temozolomide and increase in radiosensitivity via Rb‐mediated and c‐Myc/DMNT3A/MGMT pathways,31, 69 suppression of invasion58, 59, 61 by inhibition of FAK/Rac1/JNK pathway61 and induction of CSC differentiation37, 77 |

| Sublethal irradiation | Enhanced tumor cell migration and invasion involving αvβ3 integrin, MMP‐2, MMP‐9, MT1‐MMP, TIMP‐2 and BCL‐2/BAX rheostat(SR18) | ||

| Ionizing radiation | Enhanced tumor cell migration with increased expression of β3 and β1 integrins(SR19) | ||

| Bevacizumab | Resistance to the therapy is associated with up‐regulation of MMP‐2, MMP‐9, MMP‐12, TIMP1, SPARC and HIF‐2α, and with activation of bFGF‐mediated alternate angiogenesis pathway(SR22) | ||

| Bevacizumab | Treatment of tumor xenograft is associated with decrease of mitochondria, induction of glycolytic metabolites (lactate and alanine) and HIF‐1α, and activation of PI3K pathway(SR23) | ||

| Bevacizumab | Resistance to the therapy induced genes associated with a mesenchymal origin, cellular migration/invasion, and inflammation.(SR24) | ||

| Osteosarcoma | Low‐dose photon irradiation | Enhanced cell migration and invasion concomitant with up‐regulation of αvβ3 integrin(SR20) | Suppression of tumor cell survival and proliferation by inhibition of NF‐κB transcriptional activity38 and restoringβ‐catenin osteosarcoma suppressor (S. Shimozaki et al.)a |

S. Shimozaki et al., unpublished observation. AIF, apoptosis‐inducing factor; AR, androgen receptor; BAX, Bcl‐2‐associated X protein; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; BMI1, B lymphoma Mo‐MLV insertion region 1 homolog; CSC(s), cancer stem‐like cell(s); CXCL1, chemokine (C‐X‐C motif) ligand 1; CXCR4, CXC receptor type 4; DNMT3A, DNA (cytosine‐5)‐methyltransferase 3A; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EMT, epithelial‐mesenchymal transition; ERK, extracellular signal‐regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; 5‐FU, 5‐fluorouracil; HIF, hypoxia inducible factor; hTERT, human telomerase reverse transcriptase; JNK, c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase; MGMT, O6‐methylguanine DNA methyltransferase; miR, micro‐RNA; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MT1‐MMP, membrane type 1‐MMP; NF‐κB, nuclear factor‐κB; PARP1, poly [ADP‐ribose] polymerase 1;P‐gp, P‐glycoprotein (multidrug resistance); PI3K, phosphatidyl‐inositol‐3‐kinase; Rb, retinoblastoma; SPARC, secreted protein, acidic, cysteine rich; SR, supplementary reference No.; TIMP, tissue inhibitor of MMP; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor‐α; TP53INP1, tumor protein p53‐inducible nuclear protein 1; TRAIL, tumor necrosis factor‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand; WAVE2, WAS (Wiskott‐Aldrich syndrome) protein family member 2.

Regardless of the tumor type and therapeutic agent, the proposed mechanisms for invasion and resistance are attributable to molecular pathways that participate in tumor cell survival, transition to mesenchymal (EMT) and cancer stem cell (CSC) phenotypes, migration and invasion with extracellular matrix degradation, and drug efflux (Table 1). The reported molecules that mediate and interconnect these pathways include growth and transcription factors, chemokines, RAS and Rho family members (e.g. Ras, Rac1) and cell‐matrix adhesion molecules (e.g. integrin family and focal adhesion kinase [FAK]) (Table 1).9 Bevacizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody to VEGF used clinically as an anti‐angiogenic agent. Acquired resistance to bevacizumab leads to enhanced tumor cell invasion due to the metabolic shift to glycolysis and degradation and remodeling of tumor stromal tissues.(SR21–24) A better understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying the tight association between tumor invasion and therapy resistance should provide a solid rationale for the development of innovative cancer treatments.9

Aberrant GSK3β in cancer

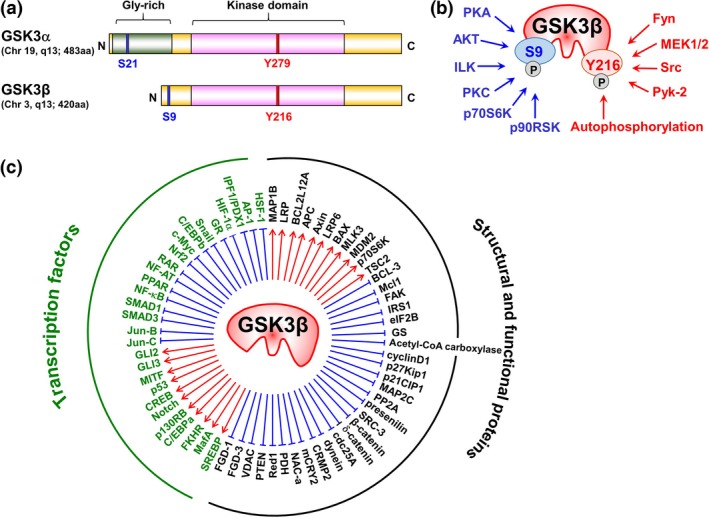

GSK3 is a family of serine/threonine protein kinases comprising two highly conserved isoforms, GSK3α and GSK3β, that show approximately 85% overall homology and 98% homology in their kinase domains. GSK3 is constitutively active in normal cells and its activity is regulated by the differential phosphorylation at serine (S) residues 21 (pGSK3αS21) and 9 (pGSK3βS9) (both inactive forms), and tyrosine (Y) residues 279 (pGSK3αY279) and 216 (pGSK3βY216) (both active forms) (Fig. 1a,b). GSK3 regulates a diverse array of physiological cellular functions via the phosphorylation of and interaction with various proteins (Fig. 1c). Although the two GSK3 isoforms share many substrates, they are not functionally identical and show some differences in their substrate specificity [reviewed in Beurel et al.10]. Negative regulation of GSK3 activity is desirable to maintain physiological cellular functions. A growing number of studies have demonstrated that deregulated GSK3 activity contributes to the pathogenesis and progression of various diseases, including glucose intolerance, neurodegenerative disorders, and chronic inflammatory and immunological diseases.10, 21 This points to GSK3 being an attractive and druggable target for a broad spectrum of diseases.22 Consequently, many GSK3 inhibitor compounds have been developed in academic and pharmaceutical institutes over recent years. Some are reported to inhibit both the α and β isoforms with different affinities,(SR25–28) while others are specific for GSK3β (reviewed in SR25,26). Among the latter compounds, it was reported that AR‐A014418 does not inhibit the activity of 26 closely related kinases and is, therefore, considered to be highly specific for GSK3β.(SR29)

Figure 1.

(a) Comparison of the structural and functional domains of the two GSK3 isoforms, (b) the sites (S9 and Y216) of phosphorylation of GSK3β by different kinases regulating GSK3β activity, and (c) the substrates of GSK3β and proteins that interact with it. (a) GSK3α (51 kD) and GSK3β (47 kD) are products of their respective genes located in chromosomes 19q13 and 3q13. The isoforms share high (98%) homology of the catalytic domains, and GSK3α has a glycine‐rich extension at the N‐terminal side. Blue and red narrow columns indicate the sites of serine (S) and tyrosine (Y) phosphorylation, respectively. (b) The kinases indicated in blue phosphorylate GSK3β‐S9 resulting in its inactivation, while those indicated in red phosphorylate GSK3β‐Y216 resulting in its activation. (c) GSK3β stabilizes/activates (red arrows) and destabilizes/inactivates (blue lines) various transcription factors as well as structural and functional proteins. AP‐1, activator protein 1; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; BAX, BCL2‐associated X protein; BCL, B‐cell lymphoma; C, C‐terminal of protein; C/EBP, CCAAT (cytosine‐cytosine‐adenosine‐adenosine‐thymidine)‐enhancer‐binding protein; cdc25A, cell division cycle 25 homolog A; CREB, cAMP (cyclic adenosine monophosphate) response element binding protein; CRMP2, collapsin response mediator protein 2; eIF2B, eukaryotic initiation factor 2B; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; FGD‐1/3, FYVE RhoGEF (guanine nucleotide exchange factor) and PH domain‐containing protein 1/3; FKHR, forkhead in rhabdomyosarcoma; Gly, glycine; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; GS, glycogen synthase; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; HIF‐1α, hypoxia inducible factor‐1α; HSF‐1, heat shock transcription factor‐1; ILK, integrin‐linked kinase; IPF1/PDX1, insulin promoter factor 1/pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1; IRS1, insulin receptor substrate 1; LRP5/6, lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5/6; MafA, musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A; MAP1B/2C, microtubule associated protein 1B/2C; Mcl1, myeloid cell leukemia 1; mCRY2, mouse cryptochrom 2; MDM2, mouse double minute 2 homolog; MEK, MAPK (mitogen‐activated protein kinase)/ERK (extracellular signal‐regulated kinase) kinase; MITF, microphthalmia‐associated transcription factor; MLK3, mixed lineage kinase 3; N, N‐terminal of protein; NAC‐α, nascent polypeptide‐associated complex subunit‐α; NF‐AT, nuclear factor of activated T‐cells; NF‐κB, nuclear factor‐κB; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2‐related factor 2; p130RB, p130 retinoblastoma; p21CIP1, p21 CDK (cyclin‐dependent kinase)‐interacting protein 1; p90RSK, p90 ribosomal protein S6 kinase; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; Pyk‐2, proline‐rich tyrosine kinase 2; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; Red1, RNA‐editing deaminase 1; S, serine; SRC‐3, steroid receptor coactivator‐3; SREBP, sterol regulatory element‐binding protein; TSC2, tuberous sclerosis complex 2; VDAC, voltage‐dependent anion channel; Y, tyrosine

Of the two GSK3 isoforms, most studies in the field of oncology have focused on GSK3β. This is partly because of the functional redundancy of the two isoforms in regulating the canonical Wnt/β‐catenin pathway, responsible for generating the most prevalent oncogenic signaling.23, 24 Based on its known effects on several proto‐oncoproteins (e.g. β‐catenin, cyclin D1 and c‐Myc), cell cycle regulators (e.g. p27Kip1) and mediators of EMT (e.g. snail) (Fig. 1c), it has long been recognized that GSK3β suppresses tumor development [reviewed in Clevers and Nusse,24 Jope et al.,25 Luo26 and McCubrey et al.27], as discussed later (Table S1).(SR30–58) Paradoxically, our earlier studies found increased expression and deregulated activity of GSK3β due to changes in the differential phosphorylation of S9 and Y216 residues in gastrointestinal cancers, glioblastoma and osteosarcoma compared to respective normal cells and tissues.28, 29, 30, 31 These observations suggested that GSK3β could participate in cancer development and progression, despite the general belief that it has tumor‐suppressive functions.25, 26, 27 We and other research groups have shown that inhibition of GSK3β activity with specific pharmacological inhibitors, or inhibition of its expression by RNA interference, can preferentially attenuate the survival and proliferation of tumor cells and induce them to undergo apoptosis. This effect has been observed not only in gastrointestinal and pancreatic cancer cells28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 35 but also in glioblastoma,31, 36, 37 osteosarcoma (S. Shimozaki, N. Yamamoto, T. Domoto, H. Nishida, K. Hayashi, H. Kimura, A. Takeuchi, S. Miwa, K. Igarashi, T. Kato, Y. Aoki, T. Higuchi, M. Hirose, R.M. Hoffman, T. Minamoto, H. Tsuchiya, unpublished data, 2016)38 and other malignant neoplasms such as gynecological and urogenital cancers,39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 soft tissue sarcomas,48, 49 hematological malignancies50, 51 and lung cancers.52, 53 This accumulating evidence firmly establishes GSK3β as a valuable target in cancer treatment.11, 12

There has been substantial interest in the molecular mechanisms by which GSK3β favors tumor progression and by which inhibition of its activity or expression attenuates tumor cell survival, immortalization and proliferation. The reported mechanisms for tumor cell survival include the nuclear factor (NF)‐κB‐mediated prosurvival pathway,34, 35, 36, 38 tumor cell resistance to apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand (TRAIL),41 and failure of the p53‐mediated tumor suppressor pathway or of the Rb‐mediated cell cycle regulation.31, 32 Preservation of telomere length by maintaining activity of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) and telomerase also immortalizes tumor cells in response to the aberrant activation of GSK3β.30 Cell proliferation pathways mediated by c‐Myc and cyclin D1 sustain tumor cell proliferation that is dependent on GSK3β.36, 39 In osteosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma, the induction of β‐catenin signaling, a well‐known tumor suppressive mechanism in these cancers, has been linked to decreased cell proliferation following GSK3β inhibition (S. Shimozaki et al., unpublished data).49 Another recent study reported that mitotic catastrophe caused by disruption of centrosome biodynamics was associated with attenuated tumor cell survival and proliferation following GSK3β inhibition.54 Importantly, GSK3β has little impact on the cell survival, immortalization and growth of normal cells, where the differential phosphorylation of S9 and Y216 residues functions to fine tune GSK3β activity.28, 29, 30, 31, 34 The growing body of evidence on the role of aberrant GSK3β in sustaining and promoting cancer cell survival, immortalization and proliferation, together with the differential effects of GSK3β inhibition on cancer and normal cells, underpins the targeting of GSK3β as a novel cancer treatment.11, 12

GSK3β mediates both the invasive phenotype and therapy resistance in refractory cancer

The dependency of cancer cells on GSK3β for their survival and proliferation has encouraged further studies on whether aberrant GSK3β participates in tumor cell invasion and therapy resistance, the two major determinants of patient outcome.3, 4, 5, 6 As shown in Table 1, most tumors that acquire pro‐invasive phenotypes as they evade therapy are susceptible to experimental treatment involving inhibition of GSK3β. Here we review what is known about the involvement of GSK3β in tumor invasion and resistance to therapy based on our previous studies in pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma. These are representative of lethal tumors and are characterized by high invasive capacity and resistance to available therapies.55, 56

GSK3β and cancer invasion

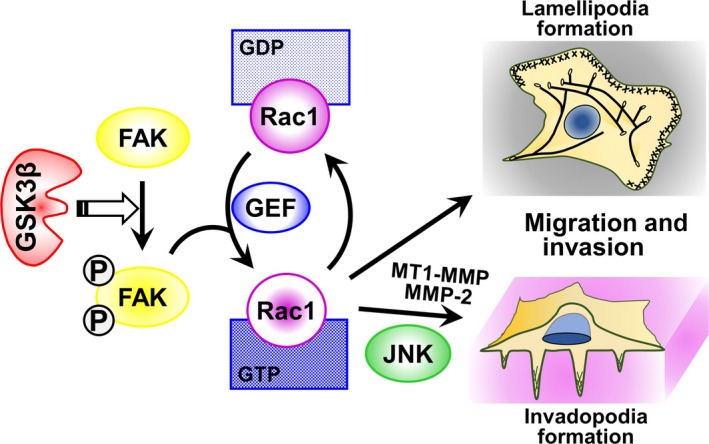

While GSK3β plays pivotal roles in cytoskeletal organization, cell polarity and migration in the physiological processes of organogenesis and wound healing,57 little is known about its role in cancer cell motility, migration and invasion. Earlier studies showed that lithium chloride and some indirubins, both classical GSK3‐inhibiting agents, inhibited the migration and invasion of glioblastoma cells, but the mechanism underlying this effect was not clear.58, 59 Subsequently, we demonstrated that inhibition of GSK3β by a specific pharmacological inhibitor and by RNA interference decreases the capacity for migration and invasion of pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma cells and of their tumors in animal models.60, 61 Morphologically, these effects were associated with reduced formation of lamellipodia and invadopodia, the horizontal and vertical cellular surface microarchitectures, respectively, that drive cell migration, stromal degradation and invasion.62, 63 Inhibition of GSK3β disrupted the functional subcellular colocalization of Rac164 and cortactin63 with the cytoskeletal molecule F‐actin in lamellipodia and invadopodia, respectively. These changes in the pro‐invasive phenotype of tumor cells following GSK3β inhibition coincide with the suppression of molecular pathways mediated by focal adhesion kinase (FAK),65 guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEF)/Rac164, 66 and c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase (JNK). This results in decreased expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)‐2 and membrane type (MT) 1‐MMP. Our observations therefore suggest that GSK3β sustains tumor invasion via the promotion of morphological and functional pro‐invasive cellular phenotypes and that the molecular axis involves FAK, GEFs/Rac1 and JNK (Fig. 2).60, 61

Figure 2.

Putative molecular pathway through which deregulated GSK3β promotes tumor cell migration and invasion. The exact molecular pathway by which GSK3β mediates the activation of FAK (open arrow) remains to be determined. FAK, focal adhesion kinase; GDP, guanosine diphosphate; GEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; GTP, guanosine triphosphate; JNK, c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MT1‐MMP, membrane type 1‐MMP; circled P, phosphorylation.

Subsequent to our studies,60, 61 other workers have reported the proinvasive effect of GSK3β in pancreatic, colorectal and breast cancer cells in association with modulation of cytoskeletal organization and cytokine‐mediated matrix degradation.67, 68. These studies highlight the pivotal role of GSK3β in tumor invasion and probably also in metastatic spread.

GSK3β and cancer therapy resistance

The combination of multiple agents having different targets and mechanisms of actions is important in the treatment of cancer in order to optimize the therapeutic effects and minimize the adverse effects. This is particularly relevant for the treatment of refractory cancer, and, hence, molecular‐targeted therapy is often combined with conventional chemotherapeutics and/or radiation therapy, as well as with other targeted agents.7, 8 As discussed above, accumulating evidence on the effects of GSK3β inhibition against cancer cell survival and proliferation has led us to address whether this could be used in combination with chemotherapy and irradiation.

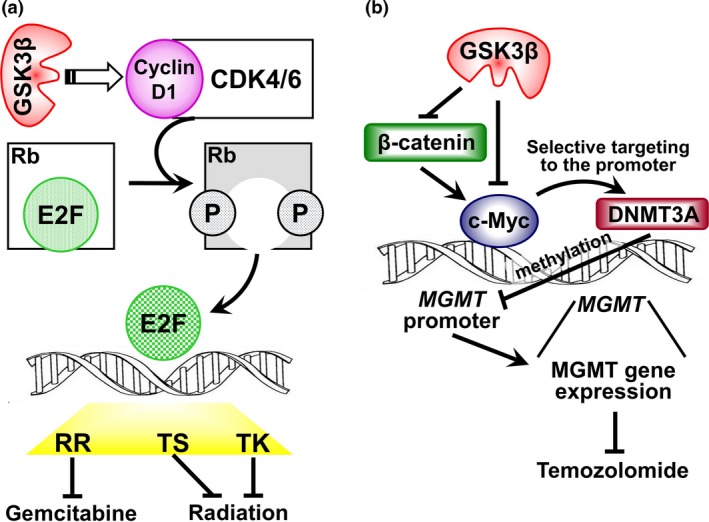

The standard treatment modalities prescribed are often ineffective in patients with refractory tumors such as pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma.55, 56 We have shown that administration of a GSK3β‐specific pharmacological inhibitor (e.g. AR‐A014418)(SR29) at a dose below that which results in a therapeutic effect when given on its own can significantly enhance the cytotoxic effects of temozolomide and gemcitabine.31, 60, 69, 70 These are the standard chemotherapeutic agents prescribed for patients with glioblastoma and pancreatic cancer, respectively.55, 56 Low‐dose GSK3β inhibitor given in combination with chemotherapeutic agents had additive and synergistic effects. Investigation of the underlying molecular mechanism is crucial to justify treatment combinations of GSK3β inhibitor with other anti‐cancer therapeutics (Fig. 3). In glioblastoma, the combined effect was attributed to modulation of the mouse double minute (Mdm)2/p53 and c‐Myc‐mediated pathways resulting in epigenetic silencing of O6‐methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), a clinically proven biomarker of temozolomide efficacy56 in tumor cells (Fig. 3b).31, 69 In pancreatic cancer, inhibition of tumor GSK3β activity decreased cyclin D1/cyclin‐dependent kinase (CDK)4/6 complex‐dependent phosphorylation of Rb tumor suppressor protein.60 One of the important functions of Rb is to bind the oncogenic transcription factor E2F1 and inhibit its transcriptional activity.71, 72 GSK3β may, therefore, sensitize pancreatic cancer to gemcitabine by downregulating the expression of ribonucleotide reductase, a well‐known pharmacological biomarker of gemcitabine55 that is regulated by the Rb/E2F pathway (Fig. 3a).71, 72 In addition to modulation of this pathway, we found that downregulation of the TP53INP1 gene (encoding tumor p53‐induced‐nuclear‐protein 1) involved in DNA repair is associated with the chemosensitizing effect of GSK3β inhibitor.70 The GSK3β inhibitor used in these studies also sensitized both pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma to ionizing radiation.31, 60 This radio‐sensitizing effect may depend on the restoration of Rb function following GSK3β inhibition, resulting in the inability of E2F1 to induce the transcription of thymidylate synthase and thymidine kinase (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Putative molecular pathway that links GSK3β activity with the resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to DNA damage induced by gemcitabine and ionizing radiation. The effects of GSK3β on E2F‐dependent gene transcription and on the expression of RR, TS and TK remain to be determined. CDK, cyclin‐dependent kinase; E2F, E2 factor; circled P, phoshorylation; Rb, retinoblastoma (tumor suupressor protein); RR, ribonucleotide reductase; TK, thymidine kinase; TS, thymidylate synthase. (b) Regulation of MGMT expression by GSK3β signaling in glioblastoma. GSK3β inhibition results in c‐Myc activation directly and via activation of β‐catenin‐mediated signaling, which consequently increases recruitment of DNMT3A by c‐Myc to the MGMT promoter, thus increasing de novo DNA methylation in the MGMT promoter. The methylated status of the MGMT promoter increases the sensitivity of glioblastoma to temozolomide. DNMT3A, DNA (cytosine‐5)‐methyltransferase 3A; MGMT, O6‐methylguanine DNA methyltransferase.

Other recent studies have also reported that GSK3β inhibition allows therapy‐resistant colon and pancreatic cancer cells to become susceptible to 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU),73 and renal cell carcinoma cells to become susceptible to a synthetic multikinase inhibitor (sorafenib) that targets growth signaling and angiogenesis.74 Together, these studies suggest that GSK3β participates in multiple molecular pathways used by various cancer types to evade chemotherapy, radiotherapy and targeted therapies.

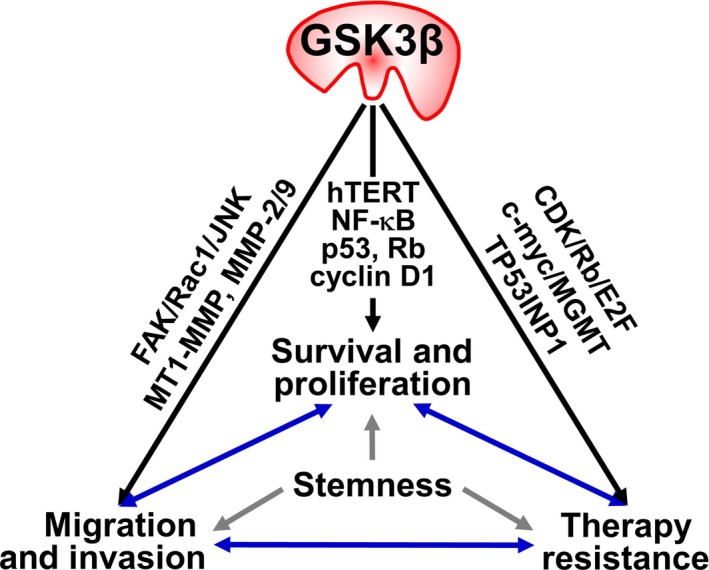

Collectively, a growing body of experimental evidence supports the notion that GSK3β is a molecular “hub” that mediates and connects various pathways responsible for tumor invasion and resistance to therapy. Together with the role of GSK3β in promoting tumor cell survival and proliferation and its differential functions between tumor and normal cells [reviewed in Miyashita et al.11 and McCubrey et al.12], this evidence reinforces the promise of novel cancer therapeutic strategies that target GSK3β.

Future perspectives

Targeting of the biological pathways that link tumor invasion and therapy resistance is clearly an attractive prospect for the development of innovative cancer treatments. Another important challenge is to understand the biology of cancer initiating or stem‐like cells (CSC) so that “stemness” phenotypes can also be targeted. Based on the clonal evolution model of tumorigenesis and on the normal stem cell concept, CSC are conceptually defined as a population of tumor cells with self‐renewing and pluripotent capacity.13 CSC have been identified in a wide range of hematopoietic malignancies and solid tumors and are assumed to be progenitors of the entire neoplastic cell population. One of the most striking characteristics of CSC is their influence on tumor cell plasticity, intra‐tumor heterogeneity, invasion and metastasis, therapy resistance and tumor relapse after surgery and adjuvant treatment.14, 75 Eradication of CSC is, therefore, of paramount clinical importance for combatting refractory cancer.15, 76

GSK3β has pivotal functions in normal cell biology10, 21, 22 and is also central to the processes of cancer cell survival, proliferation, invasion and therapy resistance, as discussed above. A number of studies have reported that CSC phenotypes share unique molecular pathways and tumor–environment interactions that are also associated with tumor invasion and therapy resistance.14, 75 This leads us to propose a working hypothesis whereby GSK3β underlies the basal mechanism for sustaining the CSC phenotype (Fig. 4). Recent studies have shown that GSK3β negatively controls the differentiation of malignant glioma cells,77 and that GSK3β inhibition results in depletion of cancer stem‐like or progenitor‐like cells and attenuation of metastatic spread in prostate cancer.78 Consistent with the physiological roles of GSK3β in negatively regulating canonical Wnt/β‐catenin and hedgehog signaling,10, 23, 24 inhibition of GSK3β is a prerequisite for the maintenance of “stemness” phenotypes in embryonic and hematopoietic stem cells.79, 80 Therefore, future work should aim to understand the influence of GSK3β on both tumor and normal stem cell phenotypes. This knowledge can be applied for the development of novel cancer treatments that target GSK3β.

Figure 4.

Involvement of GSK3β in the representative pathological hallmarks of cancer. GSK3β positively regulates the distinct molecular pathways and participates in survival, proliferation, migration and invasion of tumor cells and their insensitivity and resistance to cancer therapy. The cancer stemness phenotypes might underlie the process of these pathological hallmarks. Abbreviations are defined in Figures 1, 2 and 3.

One of the concerns about targeting GSK3β for cancer treatment is that its inhibition may promote the progression of existing tumors [reviewed in Takahashi‐Yanaga22, Jope et al.,25 Luo26 and McCubrey et al.27]. A number of studies have focused on the putative tumor suppressive role of GSK3β (Table S1).(SR30–58) Many of these report inactivation or activation of GSK3β as a mediating event in pathways leading to tumor progression or suppression, respectively. An inverse association between tumor expression of GSK3β (either total or active form pGSK3βY216) and the survival of cancer patients has been reported.(SR33,36,37) Other studies found causal links between pharmacological GSK3β inhibition and/or depletion of GSK3β expression (e.g. gene knockout and RNA interference) or activity (e.g. recombinant kinase‐dead or constitutively active mutant form) and tumor cell survival, proliferation(SR40,52) and susceptibility to cancer therapies.(SR32,34,58) GSK3β inhibition strategies and the development of GSK3β‐targeted agents therefore require careful evaluation to determine whether the tumor promoting function of GSK3β is counteracted by its putative tumor suppressor function in different cancer types.

The development and administration of GSK3β inhibitors for the treatment of chronic diseases, including diabetes mellitus, neurodegenerative disorders and cancer, requires serious awareness of the safety issues. A major concern is whether and how GSK3β can be targeted to treat disease, because its systemic inhibition may lead to unwanted effects by disrupting multiple biological pathways (Fig. 1c). Most notably, long‐term inhibition of GSK3β may initiate tumorigenesis due to its role in suppressing proto‐oncogenic pathways, in particular that are mediated by β‐catenin [reviewed in Takahashi‐Yanaga22, Jope et al.,25 Luo26 and McCubrey et al. 27]. A previous study showed that genetic deletion of GSK3β in mammary epithelial cells resulted in β‐catenin activation and induced intraepithelial neoplasia that progressed to the development of adenosquamous carcinoma.(SR51) Moreover, overexpression of wild‐type and constitutively active mutant GSK3β in 12‐O‐tetradecanoylpholbor‐13‐acetate (TPA)‐mediated, transformation‐resistant mouse epidermal cells suppressed EGF‐mediated and TPA‐mediated anchorage‐independent growth in soft agar and tumorigenicity in rodents (Table S1).(SR56) However, there is currently no direct evidence to support tumor development in vivo following treatment with a GSK3β inhibitor [reviewed in Miyashita et al.11 and SR27]. As discussed in previous studies that report cancer therapeutic effects of GSK3β inhibition (Table 1), none of the available experimental GSK3β inhibitors induces neoplastic transformation of non‐neoplastic (normal) cells or tumor development in experimental animal models [reviewed in Miyashita et al.11 and SR27]. Long‐term prescription of lithium, the only GSK3β inhibitor approved for the treatment of bipolar disorder since the 1950s, has not been associated with an increased risk of cancer or death from cancer.(SR59) Post‐translational regulation of GSK3β activity via the phosphorylation of S9 and Y216 (pGSK3βS9 versus pGSK3βY216) (Fig. 1b) in response to various stimuli could partly underlie a mechanism that protects normal cells from the detrimental effects of GSK3β inhibition.

Despite the concerns outlined above, clinical trials for neurodegenerative diseases and cancer have tested some seed pharmacological GSK3(β) inhibitor compounds and also approved medicines with the ability to inhibit GSK3β activity (Table S2). The former trials include AZD‐1080 (AstraZeneca) for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (phase I), and NP031112 (tideglusive; Noscira SA) for the treatment of progressive supranuclear palsy (NCT01049399: phase IIb)(SR60,61) and of Alzheimer's disease (NCT01350362: phase II).(SR62,63) Clinical trials for cancer treatment have used LY2090314 (Eli Lilly) alone for acute leukemia (NCT01214603: phase II), and the same compound in combination: (i) with gemcitabine, the combined folate, 5‐FU and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) regimen or the combined gemcitabine and nab‐paclitaxel regimen for metastatic pancreatic cancer (NCT01632306: phase I/II); and (ii) with pemetrexed and carboplatin for advanced or metastatic solid cancer (NCT01287520: phase I).(SR64,65) Our group is undertaking the phase I/II clinical trials by repurposing approved GSK3β‐inhibiting medicines (combined cimetidine, lithium, olanzapine and valproate regimen) in combination with gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic cancer (UMIN000005095) and with temozolomide for recurrent glioblastoma (UMIN000005111) (T. Furuta, H. Sabit, D. Yu, K. Miyashita, M. Kinoshita, M. Kinoshita, Y. Hayashi, Y. Hayashi, T. Minamoto, M. Nakada, unpublished data, 2016).

Currently, information regarding the side effects of GSK3β inhibitors is limited because the clinical trials have evaluated only a small number of seed compounds and also because lithium chloride is the only currently approved inhibitor for clinical use. It is, therefore, difficult to predict what serious adverse events, if any, will occur in patients treated with GSK3β inhibitors. The extent of GSK3β inhibition and the differential effects between normal and diseased cells/tissues (therapeutic window) are critical determining factors for therapeutic efficacy and undesirable side effects. It is clear that GSK3β activity is deregulated in various pathological conditions, including many, but not all, cancer types (Table 1).10, 11, 12, 22, 25, 26, 27 Identifying the range of GSK3β inhibition that is efficient for treatment of disease but which results in minimal detrimental effects to normal tissues and organs will be important for the clinical application of GSK3β inhibitors. Numerous studies have shown that, in addition to differential phosphorylation at S9 and Y216 residues (Fig. 1a,b), the subcellular localization of GSK3β together with various upstream pathways can regulate the expression and activity of this kinase [reviewed in Beurel et al.10 and Takahashi‐Yanaga22]. New classes of GSK3β inhibitors that spatially and temporally control the expression and activity of GSK3β may therefore be required to reduce the risk of adverse events such as carcinogenesis that may be associated with long‐term GSK3β inhibition.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Table S1. Previous studies reporting the putative tumor suppressor roles of GSK3β.

Table S2. Clinical trials of GSK3β inhibitors for treatment of diseases.

Data S1. Supplementary references.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Barry Iacopetta (University of Western Australia) for critical review of the manuscript. This study was supported by Grant‐in‐Aids for Scientific Research (TD, IVP, TS, MN and TM) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Technology and Culture; from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and the Extramural Collaborative Research Grant of Cancer Research Institute, Kanazawa University.

Cancer Sci 107 (2016) 1363–1372

Funding Information

Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Technology and Culture; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Extramural Collaborative Research Grant of Cancer Research Institute, Kanazawa University.

References

- 1. Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 19: 1423–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011; 144: 646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Friedl P, Wolf K. Tumor‐cell invasion and migration: diversity and escape mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer 2003; 3: 362–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wan L, Pantel K, Kang Y. Tumor metastasis: moving new biological insights into the clinic. Nat Med 2013; 19: 1450–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holohan C, Van Schaeybroek S, Longley DB, Johnston PG. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 13: 714–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ramos P, Bentires‐Alj M. Mechanism‐based cancer therapy: resistance to therapy, therapy for resistance. Oncogene 2015; 34: 3617–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Al‐Lazikani B, Banerji U, Workman P. Combinatorial drug therapy for cancer in the post‐genomic era. Nat Biotechnol 2012; 30: 679–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Papadatos‐Pastos D, De Miguel Luken MJ, Yap TA. Combining targeted therapeutics in the era of precision medicine. Br J Cancer 2015; 112: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alexander S, Friedl P. Cancer invasion and resistance: interconnected processes of disease progression and therapy failure. Trends Mol Med 2012; 18: 13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beurel E, Grieco SF, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2015; 148: 114–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miyashita K, Nakada M, Shakoori A et al An emerging strategy for cancer treatment targeting aberrant glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Anti‐Cancer Agents Med Chem 2009; 9: 1114–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Bertrand FE et al GSK‐3 as potential target for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Oncotarget 2014; 5: 2881–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beck B, Blanpain C. Unravelling cancer stem cell potential. Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 13: 727–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maugeri‐Saccà M, Vigneri P, De Maria R. Cancer stem cells and chemosensitivity. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 4942–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Borah A, Raveendran S, Rochani A, Maekawa T, Kumar DS. Targeting self‐renewal pathways in cancer stem cells: clinical implications for cancer therapy. Oncogenesis 2015; 4: e177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial‐mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 2009; 139: 871–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yilmaz M, Christofori G. EMT, the cytoskeleton, and cancer cell invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2009; 28: 15–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pribluda A, de la Cruz CC, Jackson EL. Intratumoral heterogeneity: from diversity comes resistance. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 2916–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tabassum DP, Polyak K. Tumorigenesis: it takes a village. Nat Rev Cancer 2015; 15: 473–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ebos JML. Prodding the beast: assessing the impact of treatment‐induced metastasis. Cancer Res 2015; 75: 3427–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beurel E, Michalek SM, Jope RS. Innate and adaptive immune responses regulated by glycogen synthase kinase‐3 (GSK3). Trends Immunol 2010; 31: 24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takahashi‐Yanaga F. Activator or inhibitor? GSK‐3 as a new drug target. Biochem Pharmacol 2013; 86: 191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Doble BW, Patel S, Wood GA, Kockeritz LK, Woodgett JR. Functional redundancy of GSK‐3α and GSK‐3β in Wnt/β‐catenin signaling shown by using an allelic series of embryonic stem cell lines. Dev Cell 2007; 12: 957–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/β‐catenin signaling and diseases. Cell 2012; 149: 1192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jope RS, Yukaitis CJ, Beurel E. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3 (GSK3): inflammation, diseases, and therapeutics. Neurochem Res 2007; 32: 577–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luo J. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) in tumorigenesis and cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Lett 2009; 273: 194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCubrey JA, Davis NM, Abrams SL et al Diverse roles of GSK‐3: tumor promoter‐tumor suppressor, target in cancer therapy. Adv Biol Regul 2014; 54: 176–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shakoori A, Ougolkov A, Yu ZW et al Deregulated GSK3β activity in colorectal cancer: its association with tumor cell survival and proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 334: 1365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mai W, Miyashita K, Shakoori A et al Detection of active fraction of glycogen synthase kinase 3β in cancer cells by nonradioisotopic in vitro kinase assay. Oncology 2006; 71: 297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mai W, Kawakami K, Shakoori A et al Deregulated glycogen synthase kinase 3β sustains gastrointestinal cancer cells survival by modulating human telomerase reverse transcriptase and telomerase. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 6810–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miyashita K, Kawakami K, Mai W et al Potential therapeutic effect of glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibition against human glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 887–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tan J, Zhuang L, Leong HS, Iyer NG, Liu ET, Yu Q. Pharmacologic modulation of glycogen synthase kinase‐3β promotes p53‐dependent apoptosis through a direct Bax‐mediated mitochondrial pathway in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 9012–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shakoori A, Mai W, Miyashita K et al Inhibition of GSK‐3β activity attenuates proliferation of human colon cancer cells in rodents. Cancer Sci 2007; 98: 1388–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ougolkov AV, Fernandez‐Zapico ME, Savoy DN, Urrutia RA, Billadeau DD. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3β participates in nuclear factor κB‐mediated gene transcription and cell survival in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 2076–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wilson W 3rd, Baldwin AS. Maintenance of constitutive IκB kinase activity by glycogen synthase kinase‐3α/β in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 8156–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kotliarova S, Pastorino S, Kovell LC et al Glycogen synthase kinase‐3 inhibition induces glioma cell death through c‐MYC, nuclear factor‐κB, and glucose regulation. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 6643–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Korur S, Huber RM, Sivasankaran B et al GSK3β regulates differentiation and growth arrest in glioblastoma. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e7443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tang QL, Xie XB, Wang J et al Glycogen synthase kinase‐3β, NF‐κB signaling, and tumorigenesis of human osteosarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012; 104: 749–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cao Q, Lu X, Feng YJ. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3β positively regulates the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells. Cell Res 2006; 16: 671–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yin Y, Kizer NT, Thaker PH et al Glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibition as a therapeutic approach in the treatment of endometrial cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2013; 14: 16617–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liao X, Zhang L, Thrasher JB, Du J, Li B. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3β suppression eliminates tumor necrosis factor‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand resistance in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2003; 2: 1215–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mazor M, Kawano Y, Zhu H, Waxman J, Kypta RM. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase‐3 represses androgen receptor activity and prostate cancer cell growth. Oncogene 2004; 23: 7882–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhu Q, Yang J, Han S et al Suppression of glycogen synthase kinase 3 activity reduces tumor growth of prostate cancer in vivo. Prostate 2011; 71: 835–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Darrington RS, Campa VM, Walker MM et al Distinct expression and activity of GSK‐3α and GSK‐3β in prostate cancer. Int J Cancer 2012; 131: E872–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Naito S, Bilim V, Yuuki K et al Glycogen synthase kinase‐3β: a prognostic marker and a potential therapeutic target in human bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16: 5124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bilim V, Ougolkov A, Yuuki K et al Glycogen synthase kinase‐3: a new therapeutic target in renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2009; 101: 2005–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pal K, Cao Y, Gaisina IN et al Inhibition of GSK‐3 induces differentiation and impaired glucose metabolism in renal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2014; 13: 285–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zeng FY, Dong H, Cui J, liu L, Chen T. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 regulates PAX3‐FKHR‐mediated cell proliferation in human alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010; 391: 1049–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen EY, DeRan MT, Ignatius MS et al Glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitors induce the canonical WNT/β‐catenin pathway to suppress growth and self‐renewal in embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 5349–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang Z, Smith KS, Murphy M, Piloto O, Somervaille TCP, Cleary ML. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3 in MLL leukaemia maintenance and targeted therapy. Nature 2008; 455: 1205–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mirlashari MR, Randen I, Kjeldsen‐Kragh J. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3 (GSK‐3) inhibition induces apoptosis in leukemic cells through mitochondria‐dependent pathway. Leuk Res 2012; 36: 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zeng J, Liu D, Qiu Z et al GSK3β overexpression indicates poor prognosis and its inhibition reduces cell proliferation and survival of non‐small cell lung cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e91231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vincent EE, Elder DJ, O'Flaherty L et al Glycogen synthase kinase 3 protein kinase activity is frequently elevated in human non‐small cell lung carcinoma and supports tumour cell proliferation. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e114725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yoshino Y, Ishioka C. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase‐3beta induces apoptosis and mitotic catastrophe by disrupting centrosome regulation in cancer cells. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2011; 378: 607–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wen PY, Kasari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med 2009; 359: 492–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sun T, Rodriguez M, Kim L. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 in the world of cell migration. Dev Growth Differ 2009; 51: 735–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nowicki MO, Dmitrieva N, Stein AM et al Lithium inhibits invasion of glioma cells: possible involvement of glycogen synthase kinase‐3. Neuro Oncol 2008; 10: 690–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Williams SP, Nowicki MO, Liu F et al Indirubins decrease glioma invasion by blocking migratory phenotypes in both the tumor and stromal endothelial cell compartments. Cancer Res 2011; 71: 5374–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kitano A, Shimasaki T, Chikano Y et al Aberrant glycogen synthase kinase 3β is involved in pancreatic cancer cell invasion and resistance to therapy. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e55289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chikano Y, Domoto T, Furuta T et al Glycogen synthase kinase 3β sustains invasion of glioblastoma via the focal adhesion kinase, Rac1 and c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase‐mediated pathway. Mol Cancer Ther 2015; 14: 564–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Machesky LM. Lamellipodia and filopodia in metastasis and invasion. FEBS Lett 2008; 582: 2102–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Paz H, Pathak N, Yang J. Invading one step at a time: the role of invadopodia in tumor metastasis. Oncogene 2014; 33: 4193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bid HK, Roberts RD, Manchanda PK, Houghton PJ. RAC1: an emerging therapeutic option for targeting cancer angiogenesis and metastasis. Mol Cancer Ther 2013; 12: 1925–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sulzmaier FJ, Jean C, Schlaepfer DD. FAK in cancer: mechanistic findings and clinical applications. Nat Rev Cancer 2014; 14: 598–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cook DR, Rossman KL, Der CJ. Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors: regulators of Rho GTPase activity in development and disease. Oncogene 2014; 33: 4021–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ying X, Jing L, Ma S et al GSK3β mediates pancreatic cancer cell invasion in vitro via the CXCR4/MMP‐2 pathway. Cancer Cell Int 2015; 15: 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yoshino Y, Suzuki M, Takahashi H, Ishioka C. Inhibition of invasion by glycogen synthase kinase‐3beta inhibitors through dysregulation of actin re‐organisation via down‐regulation of WAVE2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015; 464: 275–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pyko IV, Nakada M, Sabit H et al Glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibition sensitizes human glioblastoma cells to temozolomide by affecting O6‐methylguanine DNA methyltransferase promoter methylation via c‐Myc signaling. Carcinogenesis 2013; 34: 2206–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shimasaki T, Ishigaki Y, Nakamura Y et al Glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibition sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine. J Gastroenterol 2012; 47: 321–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Knudsen ES, Wang JYJ. Targeting the RB‐pathway in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16: 1094–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. David Engelmann D, Pützer BM. The dark side of E2F1: in transit beyond apoptosis. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 571–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Grassilli E, Narloch R, Federzoni E et al Inhibition of GSK3β bypass drug resistance of p53‐null colon carcinomas by enabling necroptosis in response to chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19: 3820–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kawazoe H, Bilim VN, Ugolkov AV et al GSK‐3 inhibition in vitro and in vivo enhances antitumor effect of sorafenib in renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012; 423: 490–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kuhlmann JD, Hein L, Kurth I, Wimberger P, Dubrovska A. Targeting cancer stem cells: promises and challenges. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2015; 16: 38–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Li Y, Lu H, Huang Y et al Glycogen synthase kinases‐3β controls differentiation of malignant glioma cells. Int J Cancer 2010; 127: 1271–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kroon J, in‘t Veld LS, Buijs JT, Cheung H, van der Horst G, van der Pluijm G. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3β inhibition depletes the population of prostate cancer stem/progenitor‐like cells and attenuates metastatic growth. Oncotarget 2014; 5: 8986–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sato N, Meijer L, Skaltsounis L, Greengard P, Brivanlou AH. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK‐3‐specific inhibitor. Nat Med 2004; 10: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Trowbridge JJ, Xenocostas A, Moon RT, Bhatia M. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3 is an in vivo regulator of hematopoietic stem cell repopulation. Nat Med 2006; 12: 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Previous studies reporting the putative tumor suppressor roles of GSK3β.

Table S2. Clinical trials of GSK3β inhibitors for treatment of diseases.

Data S1. Supplementary references.