Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate fractal analysis as a tool to quantitatively determine the mandibular trabecular bone changes in patients with chronic renal failure (CRF).

Methods:

In the present study, fractal analysis was performed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) program with box-counting method over panoramic radiographs of 25 patients (14 females and 11 males) with CRF and 26 healthy individuals (14 females and 12 males) as a control group. The fractal dimension (FD) values of the patients and healthy individuals were compared. In addition, average biochemical parameters [parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), product of Ca and P levels (CaxP), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), vitamin D] of the patients with CRF, as measured during the 3 months before the panoramic radiographs, were compared with FD values.

Results:

According to the results, FD values of the patients with CRF were found to be statistically lower than the control group (p < 0.05). The average PTH levels of the patients with CRF were 416.16 ± 310.3 pg ml−1; average Ca levels were 8.94 ± 1.2 mg dl−1; average P levels were 5.76 ± 1.7 mg dl−1; average CaxP values were 51.12 ± 15.03; average ALP levels were 83.44 ± 36.8 U l−1; and the average vitamin D values were 19.43 ± 9.7 ng ml−1. In addition, there was no significant correlation between FD values and the biochemical parameters of the patients, and there was no correlation between age, gender and FD.

Conclusions:

The FD values of the patients with CRF were lower than those of the controls. This finding suggests that FD analysis might be a promising simple and cost-effective tool for evaluating trabecular bone structure.

Keywords: chronic renal failure, panoramic radiography, trabecular bone, fractals

Introduction

Chronic renal failure (CRF) can be described as a state of chronic and progressive deterioration in the stabilization of the liquid–solid equilibrium of the kidneys and in metabolic and endocrine functions as a result of the loss of nephrons. Many factors play a role in the development of CRF. After the development of CRF, regardless of the cause of kidney damage, end-stage renal disease develops slowly and progressively.1 As kidney disease progresses, decreased levels of vitamin D and plasma calcium (Ca) and phosphate retention increases the secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and causes hyperplasia of the parathyroid gland. As a result, secondary hyperparathyroidism develops in patients with CRF. The pathologies caused by secondary hyperparathyroidism are seen in CRF to a serious degree. The increase in PTH secretion, the decrease in vitamin D synthesis, the presence of malnutrition and metabolic acidosis cause mineral–bone disorders in patients.2

Bone changes in patients with CRF are referred to as renal osteodystrophy (ROD), and there is a specific ROD form for every level of CRF. Definitive diagnosis of these subgroups is obtained through biopsy.3 Osteoporosis, which is among one of the most common topics discussed today, is not a subgroup of ROD but a highly prevalent metabolic bone disease, caused by secondary hyperparathyroidism, in patients with CRF. Both ROD and secondary osteoporosis in patients with CRF lead to negative effects throughout the skeletal system and, in particular, the mandible. ROD leads to many complications, such as increased demineralization in jawbones, decreased trabeculation, “ground-glass” appearance, radiolucent giant cell lesions (brown tumour), metastatic soft-tissue calcification, loss of lamina dura, pulpal constriction, calcification and periodontal disorders.2 According to the report by Klemetti et al4 and Bras et al,5 the mandibular cortex thickness in post-menopausal females and in patients with CRF, as measured by panoramic radiographs, is less than that in normal individuals.

The trabecular bone shows fractal characteristics such as self-similarity and lack of well-defined scale due to its branched structure. Therefore, fractal geometrical applications and fractal dimension (FD) can be used to define the complex structure of the trabecular bone.6 Earlier diagnosis of many bone diseases has become a current issue since technology has developed and computer analyses have become universal. Over the past several years, fractal analysis, a numerical method that is used to evaluate images with complex structure by studying basic components, has been used intensively in scientific research to analyze biological images. In this method, a mathematical and morphological image processing system has been used to perform FD analysis. Many researchers (Law et al,7 Southard et al,8–10 Fazzalari and Parkinson11 and White and Rudolph12) have conducted scientific studies, which have demonstrated that this method is especially beneficial in the evaluation of patients with osteoporosis.13

Although many studies have been carried out on FD analysis, especially to evaluate osteoporosis in dentistry, there are no such studies that examine the changes in trabecular bone structure of patients with CRF. In this study, the mandibular trabecular bone structure of patients with CRF, who were receiving dialysis therapy, was examined on dental panoramic radiographs by performing fractal dimensional analysis.

Methods and materials

Study group

After this study was approved by the Atatürk University Ethics Committee, 25 patients (14 females and 11 males) with CRF, who were receiving renal replacement therapy in the Dialysis Unit in Internal Diseases Nephrology Polyclinic of Research Hospital in Atatürk University Medical Faculty, were included in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients with end-stage renal disease (Stage 5 CRF) with glomerular filtration rate <15 ml min−1 were included in the study. The average age of the patients was 37.5 years (range 24–54 years). The average duration of dialysis of the patients was 43 ± 31 months (range 12–120 months). With the aim of forming a control group, 26 individuals (14 females and 12 males) who presented to the clinic for various reasons, without any systemic diseases and not using any medicines which could affect bone metabolism, were included in the study. The average age of the individuals in the control group was 38 years (range 24–52 years).

Images

All panoramic radiographs were taken by the same X-ray technician using the same device (ProMax®; Planmeca Oy, Helsinki, Finland) in the Atatürk University Faculty of Dentistry Department of Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology. While positioning the subjects for panoramic radiographs, the criteria determined by the company that developed the device were followed. Imaging parameters were set, on average, as 62 kVp, 4 mA and 16.2 s.

Biochemistry

Biochemical parameters, including PTH, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, Ca, phosphorus (P) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), were recorded within the past 3 months before the taking radiograph. Chemistry analyzers Beckman Coulter AU-5800 and DXI-800 (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA) were used in the Atatürk University Medical Faculty Research Hospital Biochemistry Laboratory. In addition, PTH, one of the parameters that has an active role in bone-turnover metabolism, was compared with FD values totally and by dividing PTH into three separate subgroups (0–150 pg ml−1, 151–500 pg ml−1 and >500 pg ml−1).

Fractal analysis

FD analysis was carried out using the box-counting method in the mandible. Regions of interest (ROIs) were selected in the size of 35 × 30 pixels between the second premolar and first molar tooth apexes of the left mandibular segment in each radiograph (Figure 1). The ROIs were created in this way to prevent the effect of anatomical structures, such as foramen mandibular nerve canal, lamina dura and tooth root on the FD analysis. All required transactions for FD analysis were performed by the same person using the same computer (Acer Aspire E1-531; Acer Inc., New Taipei, Taiwan) and the ImageJ 1.46r image analysis program (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image). This is a version of the National Institute of Health Image with permission to be used for free by the website “http:rsb.info.nih.gov”. The method designed by White and Rudolph12 was used (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Selection of the region of interest on panoramic radiography.

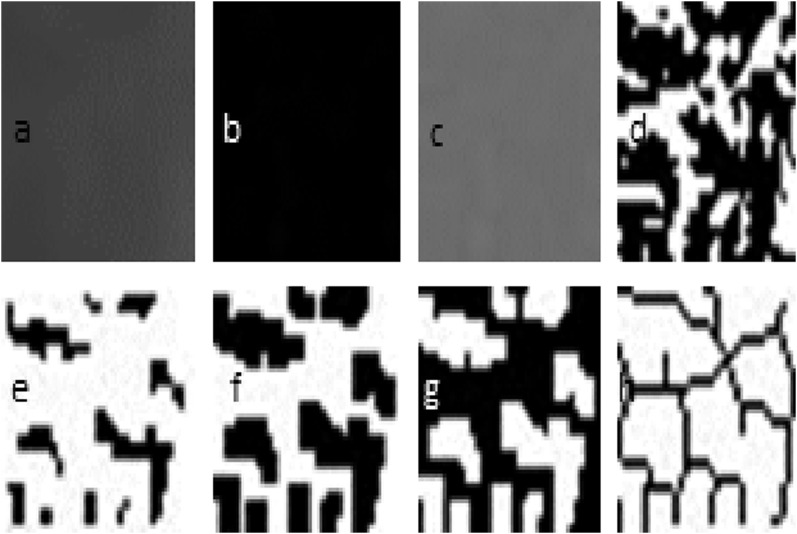

Figure 2.

Fractal dimension analysis transactions. (a) Blurred image of the cropped and duplicated region of interest; (b) the blurred image was then subtracted from the original image; (c) adding 128 to the result; (d) application of 128 threshold value; (e) erosion process; (f) dilatation process; (g) reversing; (h) skeletonizing.

Statistical analysis

The results of the study were analyzed using SPSS® software v. 22.0 (IBM Corp., New York, NY; formerly SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The Pearson correlation was used in the analysis of the correlation between the variables in the patient population; the Student's t-test was used in the comparison of FD values of the control individuals and patient population; and one-way analysis of variance test was used in the comparison of subgroups, which were formed in accordance with PTH levels with FD. Results were reported as mean ± standard error, and a level of p < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

FD values of the patients with CRF and the control subjects are presented in Table 1. FD values of the patients with CRF were significantly lower than those in the control subjects. The average FD value for patients with CRF was 1.3721 (male: 1.3620 and female: 1.3800), whereas the control average FD value was 1.4110 (male: 1.4105 and female: 1.4114). There was no correlation between age, gender and FD. The average PTH values of the patients were 416.16 ± 310.3 pg ml−1. The average ALP values were 83.44 ± 36.8 U l−1. The average vitamin D values were 19.43 ± 9.7 ng ml−1. The average Ca values were 8.94 ± 1.2 mg dl−1. The average p-values were 5.76 ± 1.7 mg dl−1, and the average product of Ca and P levels values were 51.12 ± 15.03. There was no significant correlation between the biochemical parameters of the patients with CRF (PTH, ALP, vitamin D, Ca, P) and the FD values (Table 2). In the comparison of the classification of PTH into three separate subgroups with FD values, there was also no significant correlation (Table 3).

Table 1.

Average fractal dimension (FD) values of the patients with chronic renal failure (CRF) and the individuals in the control group

| Patients with CRF | Healthy control group | p-value | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 25 | 26 | ||

| Average FD | 1.3721 | 1.4110 | 0.000 | -6.149 |

| SD | 0.266 | 0.178 | ||

| SE | 0.005 | 0.003 |

SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error.

Table 2.

Correlation analysis of fractal dimension values of the patients and other parameters

| Duration of dialysisa | Age (years) | PTH | Ca | P | CaxP | ALP | Vitamin D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractal | PC | 0.095 | −0.127 | −0.412 | −0.069 | 0.012 | −0.025 | −0.168 | 0.279 |

| Sig. | 0.653 | 0.545 | 0.041 | 0.742 | 0.955 | 0.904 | 0.422 | 0.177 | |

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; Ca, calcium; CaxP, product of calcium and phosphorus levels; PC, Pearson correlation; P, phosphorus; PTH, parathyroid hormone; Sig., significance.

Average time elapsed since entry to dialysis.

Table 3.

Fractal dimension (FD) values in accordance with parathyroid hormone (PTH) subgroup

| N | Mean | SD | SE | Minimum | Maximum | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–150 | 3 | 1.3877 | 0.018 | 0.010 | 1.3679 | 1.4048 | |

| 151–500 | 13 | 1.3761 | 0.023 | 0.006 | 1.3442 | 1.4242 | |

| >500 | 9 | 1.3611 | 0.030 | 0.010 | 1.3077 | 1.3925 | 0.249 |

| Total | 25 | 1.3721 | 0.026 | 0.005 | 1.3077 | 1.4242 |

SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error.

Discussion

Many studies have already been carried out using many methods, such as densitometric and radiomorphometric measurements, to evaluate the bone in terms of qualitative and quantitative parameters in dental radiology.2–4,14–17 Considerable research has also been carried out to evaluate the mineral density of bones in various parts of the body, especially in patients with osteoporosis, and to examine the use of radiomorphometric studies in the diagnosis of osteoporosis.18–20 In many of these studies, various parameters, which can be merged under the names of mandibular indices and mandibular cortical bone, were evaluated. Conversely, in the present study, FD analysis was performed on panoramic radiographs to examine the mandibular trabecular bone structure in patients with CRF.

The texture of the image has a structure that includes many small components and researchers have developed many methods that statistically and structurally fulfil the analysis of this texture. Fractal analysis, on the other hand, is a method of numerical texture analysis, which is based on a series of processes referred to as fractal mathematics to define this complex shape and structural patterns. The range of applications of FD, from mathematics to biology, is very wide.21 In the dental fields, researchers have discriminated between patients with gingivitis and periodontitis22 and individuals with osteoporosis, and those without osteoporosis8,10,23 by using dental radiographs and image analysis procedures. Many researchers7–12 stated that FD analysis was the most reliable, economical and easily applicable method among all the methods in the evaluation of bone tissue mentioned above. Updike and Nowzari,6 in a study carried out on periapical radiographs of patient groups who they categorized in terms of periodontal health, stated that FD is a successful method in evaluating cancellous bone changes. In addition, it was claimed that even small changes could be determined by means of FD analysis before the loss of bone happened in later stages of disease. It was also stated that the process of resorption/demineralization, which was caused by periodontal disease, decreased trabecular complexity and thus the FD value decreased in periodontal diseases.

In the present study, FD values of healthy control individuals and patients with CRF were compared and the FD values of the patients with CRF were found to be significantly lower. Since the patient and control groups studied had subjects with age and gender, a graph was constructed to compare the effects of age and gender on FD. There was no correlation between age, gender and FD. Although there is no research in the medical literature to which this study can be directly compared, many studies have been carried out on FD analysis in osteoporosis and similar diseases related to bone structure. In one similar study, Demirbaş et al24 obtained supportive results for the present study in which they carried out panoramic radiographs of 35 patients with sickle cell anaemia and found that the FD values of the patients with sickle cell anaemia were lower than those of the control group. Intertwined complex structural elements that are called “trabecular network” in the structure of alveolar bone have a FD value. In general, the higher FD value may indicate more complex structure.25 However, in fractal studies that have been performed so far, there has been no consensus on how changes of bone structure emerging in diseases affect trabecular complexity. Thus, FD values obtained in the studies are contradictory. For example, although some researchers (Ruttimann et al26 and Hua et al27) have reported that FD increases in some diseases, which creates osteoporotic effects on bone structure, many others (Demirbaş et al,24 Southard et al,9 Updike and Nowzari,6 Ergün et al13) have concluded that it decreases, as is the conclusion in the present study. Saeed et al28 asserted that demineralization and resorption, which were caused by periapical lesions in the bone, increased trabecular complexity by affecting the surface porosity, and thus the FD value increased. Researchers such as Ruttimann et al26 and Hua et al27 also reported similar results. The present argument is, however, that dilution in trabeculae due to CRF, decrease in the number and increase in lacunae between trabecula, decreased the complexity of the structure and the FD value. Shipov et al29 specified that the changes mentioned above emerged in the trabecular bone in the bone structure analysis that they carried out by means of microCT after CRF, which is created in cats in the natural period. Nevertheless, changes such as thickening and resorption in trabeculae, which are caused by various factors in bone metabolism, lead to changes in FD values. Here, many factors, such as how diseases affect bone quality, how different bones in different parts of the body are affected by this situation, anatomical variations, course of obtaining two-dimensional images, determined criteria while choosing the ROI, and different methods used in the measurement of FD play a role.6,24,30,31 It is possible that all these factors are related to different results found in studies. Southard et al10 compared their results in their own study to the study of Ruttimann et al26 and argued that the difference in the results might have been caused by the difference of the analysis methods that were used. Although there are many different approaches in the method of fractal analysis, the method of box counting is the most highly preferred.6,13 This method was the one chosen for the present study. Researchers have stated that higher box-counting values refer to more complex structures in this method, in which as a fundamental principle, trabeculae and lacunae of the trabecular bone are counted.6,13 Updike and Nowzari6 stated that there are many different methods of fractal analysis such as pixel-dilatation, mass-radius and box counting. Subsequently, different FD values might emerge and the comparison of FD values in the studies, in which different methods are used, is not possible for researchers.

There are some limitations to the present study. Firstly, panoramic radiographs represent a two-dimensional image of a three-dimensional structure. Three-dimensional exercises performed with CBCT will certainly give more valuable information. However, CBCT was not chosen because it is not a method routinely used in every patient who presents to a dentist, and CBCT delivers considerably more radiation. Another limitation is that it is not possible to histopathologically evaluate how changes in bone structure caused by ROD and osteoporosis seen in patients with CRF in this research affects trabecular structure. Dual tetracycline-marked bone biopsy is the gold-standard method in the diagnosis of ROD and in defining specific forms.3 The practice of biopsy in patients with CRF, however, is an undesirable intervention despite specific clinical outlooks due to the fact that it is an invasive, painful, expensive and non-practical method. Routinely, biochemical parameters are used. The average levels of serum Ca, P, PTH, ALP and vitamin D of patients with CRF, which were evaluated in the past 3 months, were used in this study for comparison with FD values. No statistically significant result was found between biochemical profiles and FD values of the patients.

In conclusion, in this study, the FD values of patients with CRF were found to be lower than those in control subjects. This finding suggests that FD analysis might be a promising, simple and cost-effective tool for evaluating trabecular bone structure. Nevertheless, with the aim of proving it to be a reliable method itself, histopathological examinations supported with biopsies and studies including wider populations need to be carried out.

References

- 1.Nadir I, Topçu S, Gültekin F, Yönem Ö. The assessment of etiology in chronic renal failure. CU faculty Medicine Magazine 2002; 24: 62–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Çağlayan F, Dağistan S, Keleş M. The osseous and dental changes of patients with chronic renal failure by CBCT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2015; 44: 20140398. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20140398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller PD. Renal osteodystrophy. In: Hochberg MC, ed. Rheumatology. 4th edn. Ankara, Turkey: Rotatıp Kitabevi; 2011. pp. 1995–2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klemetti E, Kolmakov S, Kröger H. Pantomography in assessment of the osteoporosis risk group. Scand J Dent Res 1994; 102: 68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bras J, van Ooij CP, Abraham-Inpijn L, Wilmink JM, Kusen GJ. Radiographic interpretation of the mandibular angular cortex: a diagnostic tool in metabolic bone loss. Part II. Renal osteodystrophy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1982; 53: 647–50. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(82)90356-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Updike SX, Nowzari H. Fractal analysis of dental radiographs to detect periodontitis-induced trabecular changes. J Periodontal Res 2008; 43: 658–64. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01056.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Law AN, Bollen AM, Chen SK. Detecting osteoporosis using dental radiographs: a comparison of four methods. J Am Dent Assoc 1996; 127: 1734–42. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Southard TE, Southard KA, Jakobsen JR, Hillis SL, Najim CA. Fractal dimension in radiographic analysis of alveolar process bone. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1996; 82: 569–76. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80205-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Southard TE, Southard KA, Krizan KE, Hillis SL, Haller JW, Keller J, et al. Mandibular bone density and fractal dimension in rabbits with induced osteoporosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000; 89: 244–9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/moe.2000.102223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Southard TE, Southard KA, Lee A. Alveolar process fractal dimension and postcranial bone density. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001; 91: 486–91. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/moe.2001.112598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazzalari NL, Parkinson IH. Fractal properties of cancellous bone of the iliac crest in vertebral crush fracture. Bone 1998; 23: 53–7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S8756-3282(98)00063-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White SC, Rudolph DJ. Alterations of the trabecular pattern of the jaws in patients with osteoporosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999; 88: 628–35. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1079-2104(99)70097-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ergün S, Saraçoglu A, Güneri P, Ozpinar B. Application of fractal analysis in hyperparathyroidism. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2009; 38: 281–8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr/24986192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman WG, Ramirez JA, Belin TR, Chon Y, Gales B, Segre GV, et al. Development of a dynamic bone in patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism after intermittent calcitriol therapy. Kidney Int 1994; 46: 1160–6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ki.1994.380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White SC. Oral radiographic predictors of osteoporosis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2002; 31: 84–92. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenzel A, Gotfredsen E, Borg E, Gröndahl HG. Impact of lossy image compression on accuracy of caries detection in digital images taken with a storage phosphor system. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1996; 81: 351–5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80336-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeytinoğlu M, İlhan B, Dündar N, Boyacioğlu H. Fractal analysis for the assessment of trabecular peri-implant alveolar bone using panoramic radiographs. Clin Oral Investig 2015; 19: 519–24. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00784-014-1245-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devlin H, Karayianni K, Mitsea A, Jacobs R, Lindh C, van der Stelt P, et al. Diagnosing osteoporosis by using dental panoramic radiographs: the OSTEODENT project. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 104: 821–8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cakur B, Sahin A, Dagistan S, Altun O, Caglayan F, Miloglu O, et al. Dental panoramic radiography in the diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Int Med Res 2008; 36: 792–9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/147323000803600422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kademoğlu O. Comparison of the panoramic mandibular index and the panoramic radiographic density with DEXA in the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Institute of Health Sciences, Department of Oral Diagnosis and Radiology. PhD Thesis. Samsun, Turkey: University of Ondokuz Mayis; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith TG, Jr, Lange GD, Marks WB. Fractal methods and results in cellular morphology—dimensions, lacunarity and multifractals. J Neurosci Methods 1996; 69: 123–36. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0270(96)00080-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shrout MK, Roberson B, Potter BJ, Mailhot JM, Hildebolt CF. A comparison of 2 patient populations using fractal analysis. J Periodontol 1998; 69: 9–13. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1902/jop.1998.69.1.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bollen AM, Taguchi A, Hujoel PP, Hollender LG. Fractal dimension on dental radiographs. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2001; 30: 270–5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj/dmfr/4600630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demirbaş AK, Ergün S, Güneri P, Aktener BO, Boyacioğlu H. Mandibular bone changes in sickle cell anemia: fractal analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008; 106: e41–8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caligiuri P, Giger ML, Favus M. Multifractal radiographic analysis of osteoporosis. Med Phys 1994; 21: 503–8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1118/1.597390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruttimann UE, Webber RL, Hazelrig JB. Fractal dimension from radiographs of peridental alveolar bone. A possible diagnostic indicator of osteoporosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992; 74: 98–110. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(92)90222-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hua Y, Nackaerts O, Duyck J, Maes F, Jacobs R. Bone quality assessment based on cone beam computed tomography imaging. Clin Oral Implants Res 2009; 20: 767–71. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saeed SS, Ibraheem UM, Alnema MM. Quantitative analysis by pixel intensity and fractal dimensions for imaging diagnosis of periapical lesions. Int J Enhanced Res Sci Technol Eng 2014; 3: 138–44. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shipov A, Segev G, Meltzer H, Milrad M, Brenner O, Atkins A, et al. The effect of naturally occurring chronic kidney disease on the micro-structural and mechanical properties of bone. PLoS One 2014; 9: e110057. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tosoni GM, Lurie AG, Cowan AE, Burleson JA. Pixel intensity and fractal analyses: detecting osteoporosis in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women by using digital panoramic images. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006; 102: 235–41. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geraets WG, van der Stelt PF. Fractal properties of bone. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2000; 29: 144–53. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj/dmfr/4600524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]