Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the utility of the application of a thyroid shield in intraoral radiography when using rectangular collimation.

Methods:

Experimental data were obtained by measuring the absorbed dose at the position of the thyroid gland in a RANDO® (The Phantom Laboratory, Salem, NY) male phantom with a dosemeter. Four protocols were tested: round collimation and rectangular collimation, both with and without thyroid shield. Five exposure positions were deployed: upper incisor (Isup), upper canine (Csup), upper premolar (Psup), upper molar (Msup) and posterior bitewing (BW). Exposures were made with 70 kV and 7 mA and were repeated 10 times. The exposure times were as recommended for the exposure positions for the respective collimator type by the manufacturer for digital imaging. The data were statistically analyzed with a three-way ANOVA test. Significance was set at p < 0.01.

Results:

The ANOVA test revealed that the differences between mean doses of all protocols and geometries were statistically significant, p < 0.001. For the Isup, thyroid dose levels were comparable with both collimators at a level indicating primary beam exposure. Thyroid shield reduced this dose with circa 75%. For the Csup position, round collimation also revealed primary beam exposure, and thyroid shield yield was 70%. In Csup with rectangular collimation, the thyroid dose was reduced with a factor 4 compared with round collimation and thyroid shield yielded an additional 42% dose reduction. The thyroid dose levels for the Csup, Psup, Msup and BW exposures were lower with rectangular collimation without thyroid shield than with round collimation with thyroid shield. With rectangular collimation, the thyroid shield in Psup, Msup and BW reduced the dose 10% or less, where dose levels were already low, implying no clinical significance.

Conclusions:

For the exposures in the upper anterior region, thyroid shield results in an important dose reduction for the thyroid. For the other exposures, thyroid shield augments little to the reduction achieved by rectangular collimation. The use of thyroid shield is to be advised, when performing upper anterior radiography.

Keywords: dental radiography, thyroid gland, radiation protection, radiation dosimetry

Introduction

Intraoral radiography is a well-established diagnostic modality in dentistry. However, the use of X-rays is potentially detrimental to the patient and the operators. This means that it is important to minimize the radiation dose. Therefore, each exposure should be justified to benefit the individual patient. When it is justified, the exposure should be executed following the ALARA principle, an acronym of as low as reasonably achievable.1 This can be carried out by using individualized exposure parameters, by collimation of the beam and by shielding radiosensitive organs from the primary beam and from stray radiation.

The thyroid gland is important in this respect, as it has been shown to be one of the most radiosensitive organs in the head and neck area.2,3 When performing intraoral radiography in the upper anterior region, the gland lies within the primary beam of the X-rays. In dose research, it has been observed that the organ dose to the thyroid contributes a considerable part to the total effective dose of intraoral radiography.4,5 This type of research is executed with small dosemeters at a number of locations in a phantom head. By combining the measured doses of specific locations, averaged doses for different tissue types can be calculated. After applying tissue-weighting factors that reflect the sensitivity of different organs and tissues, a weighted summation of these tissue doses is possible to calculate the effective dose of an exposure protocol. This effective dose is expressed in sievert. This is the unit that indicates the risk of occurrence of a stochastic effect as a result of the tested exposure protocol.

To prevent irradiating the thyroid gland, shielding of this organ has been proposed.6–10 This can be carried out by using a thyroid shield, thyroid collar or leaded apron with collar. The referenced studies show large dose reductions when using thyroid shielding in intraoral radiography. This being the case, it is remarkable that guidelines on radiation protection in dentistry are divided on the use of thyroid protection.

The perception that with the use of rectangular collimation the thyroid dose is already considerably reduced could be one of the reasons for this. This is reflected in the ambiguous advice in the European Guidelines.11 In this document, it is stated that “It is probable that rectangular collimation for intraoral radiography offers similar level of thyroid protection to lead shielding, in addition to its other dose reducing effects”.10 In another paragraph, this document reads “Lead shielding of the thyroid gland should be used in those cases where the thyroid is in line of, or very close to, the primary beam”.10 This is the case in intraoral radiography of the upper anterior region; so, this recommendation contradicts the former.

The American Dental Association in their 2006 publication “The use of dental radiographs: update and recommendations” refers to the National Council on Radiological Protection and Measurement (NCRP) report No. 145 and recommends: “Thyroid shielding with a leaded thyroid shield or collar is strongly recommended for children and pregnant females, as these patients may be especially susceptible to radiation effects”.12,13 The American Thyroid Association (ATA) published a “Policy statement on thyroid shielding during diagnostic medical and dental radiology” in 2013.14 One of the conclusions in this document is: “The ATA (…) endorses the recommendations of NCRP-145. However, the ATA also urges a reconsideration of the less stringent requirement for thyroid shielding in adults as compared to children. Adult risk for radiation-induced thyroid cancer may be less, but still merits efforts to reduce it, given that the use of shielding is safe and readily available. The ATA also recommends that efforts be made to encourage and monitor compliance with the American Dental Association and NCRP guidelines and to reduce, as much as possible, the areas of ambiguity in them”.13 The handheld thyroid shield is a practical and indeed readily available way to protect the thyroid gland in intraoral radiography while performing periapical imaging in the upper arch and during bitewing (BW) exposures (Figure 1). In light of the lack of clarity considering the guidelines, the utility of thyroid shield in intraoral radiography needs further investigation. Especially, the question if its yield is still worthwhile when rectangular collimation is used.

Figure 1.

Handheld thyroid shield during upper incisor periapical exposure.

To investigate this question, we must consider the effect of collimation and shielding on dose levels at the site of the thyroid in detail. The beam of the intraoral exposure is collimated and it is very well possible that the thyroid gland is partially irradiated during intraoral exposures. When small dosemeters are placed in the phantom in the area of the thyroid, as in classical dose research, it is possible that the dosemeter is just inside the primary beam, but a large part of the thyroid is not. This results in an overestimation of the thyroid dose. The other way around it is also possible that the dosemeter is just outside the primary beam while the thyroid receives a considerable dose, which is then not reflected in the resulting data. Therefore, a way of measuring the dose level in the area of the thyroid gland is indicated that can reflect partial exposures as an average dose to the complete thyroid. The use of a detector that gives the average of the dose in a defined area is a way to overcome the problems that are posed by incorrect reflection of partial exposure. A solid-state survey detector is such a dosemeter that can average the dose level measured over an area. Using this type of detector at the position of the thyroid gland in the phantom necks during exposures with round collimation and rectangular collimation, both with and without a handheld thyroid shield in place, will reflect the effects on the radiation levels at the site of the thyroid. In this way, it is possible to assess if handheld thyroid shielding does still reduce thyroid dose when rectangular collimation is applied. By measuring only at the position of the thyroid, it is not possible to calculate the effective dose to the patient. As we are interested in the yield of thyroid shielding during different protocols, the recording of the differences between these dose levels is more important than being able to calculate effective doses. When the effects of different protocols are known on thyroid dose, it is possible by using the data from existing dose research to estimate the effects of thyroid shielding for the effective dose.

The aim of this study was therefore to compare the dose levels in the area of the thyroid gland for protocols with and without thyroid shield, when rectangular collimation or round collimation is used during BW and periapical exposures of different maxillary regions.

Methods and materials

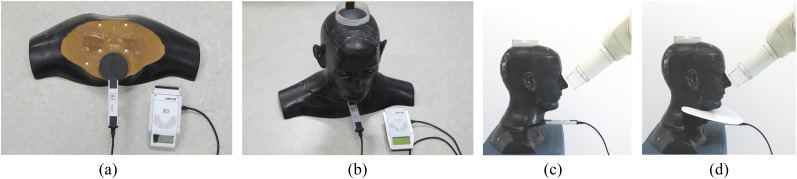

For this experiment, the head and neck of a RANDO® (The Phantom Laboratory, Salem, NY) adult male radiological phantom was used. The phantom contained a human skull embedded in a tissue-equivalent material, as is often used in radiation dosimetry.15 The intraoral X-ray unit used was an Instrumentarium FOCUS™ (Instrumentarium Corp., Tuusula, Finland). The machine had recently passed a performance test, where the fluctuations of its output were found to be ±0.75%. This device was used with two different exchangeable tubes: one 22.86-cm (9-inch) tube with round collimation of 60-mm diameter at the end of the tube and one tube of 30.48-cm (12-inch) length with a rectangular collimation of 35 × 45 mm at the end of the tube. Exposures were made with and without a thyroid shield of the type “Protectoray” (Hager & Werken GmbH & Co. KG, Duisburg, Germany), with an attenuating layer of 0.5-mm lead as proposed in the literature.6 At the level of the thyroid gland in the midline of the neck of the phantom, the dose level was measured by means of the Unfors RaySafe Xi survey detector (Unfors RaySafe AB, Billdal, Sweden). The detector is built with silicon diodes and reports the average of the dose (Kerma in gray) measured at the active area with a radius of 28 mm. It was recently calibrated traceable to the National Institute of Standards and Technology and Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt standards. The accuracy of this dosemeter was stated to be ±1.3% during calibration. The active area of the dosemeter was placed over the area where the thyroid gland is positioned inside the contour of the neck and before the body of the cervical vertebra number 4 (Figure 2a). The next slabs of the phantom were positioned over the dosemeter, as can be seen in Figure 2b. After this, the exposures were performed with and without thyroid shield with the two different collimators, as can be seen in Figure 2c,d. It was not possible to place an image detector in the mouth of the phantom; therefore, this aspect of the experimental setup deviates from the clinical situation.

Figure 2.

(a) Position of the detector on the lower slabs of the phantom. The round active detecting area is inside the contour of the neck and anterior to the cervical vertebral body. (b) Phantom assembled on top of the detector. (c) Experimental setting during upper incisor exposure of the phantom without thyroid shield with detector in place and (d) with thyroid shield.

The exposure geometries of the phantom represented upper incisor (Isup) exposure, upper canine (Csup) exposure, upper premolar, upper molar (Msup) and posterior BW. The horizontal and vertical angulations of these exposure geometries were based on published values and are shown in Table 1.16 The end of tube to skin distance was kept at 1 cm. The distance from the focus to the centre of the detector with the rectangular collimation was circa 46 cm and 38 cm with the round collimation. All five exposure geometries were performed in four modalities: the two types of tubes with and without thyroid shield present. The 5 exposures geometries were all executed 10 times. The average dose level per exposure geometry per modality was calculated, as well as the standard deviation. A total of 200 exposures were performed (5 exposure geometries × 4 modalities × 10 exposures). The measurements were corrected for background radiation by subtracting from the measurement value the product of the measurement time and the background radiation tempo.

Table 1.

Horizontal and vertical tube angles used for the different exposure geometries

| Geometry | Vertical angle (°) | Horizontal angle (°) |

|---|---|---|

| Isup | 40 | 0 |

| Csup | 45 | 45 |

| Psup | 30 | 75 |

| Msup | 20 | 85 |

| BW | 10 | 75 |

BW, posterior bitewing; Csup, upper canine; Isup, upper incisor; Msup, upper molar; Psup, upper bicuspid.

The exposure settings were 70 kV and 7 mA. The exposure time was set according to the recommendations provided by the manufacturer (Table 2). In some cases, the exposure time was shortened when overexposure of the survey detector occurred during measurements. This was the case during Isup and Csup exposures. The resulting dose measurements were recalculated to correspond with the recommended exposure times for the respective exposure positions. These recommended exposures times for the rectangular collimator were twice as long as those for the round collimator. All images were taken from the right side of the phantom assuming symmetry. For the incisor and canine exposures, the rectangular field was set vertical, while for the premolar, molar and BW exposures, the field was set horizontal.

Table 2.

Recommended exposure times of the Instrumentarium Imaging FOCUS™ (Instrumentarium Corp., Tuusula, Finland) in seconds

| Collimator type | Isup (s) | Csup (s) | Psup (s) | Msup (s) | BW (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round collimator (22.86 cm or 9 inches) | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.16 |

| Rectangular collimator (30.48 cm or 12 inches) | 0.16 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.32 |

BW, posterior bitewing; Csup, upper canine; Isup, upper incisor; Msup, upper molar; Psup, upper bicuspid.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed with IBM SPSS® Statistics 22.0 (IBM Corp., New York, NY; formerly SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Three-way ANOVA tests were performed, and significance was set at p < 0.01.

Results

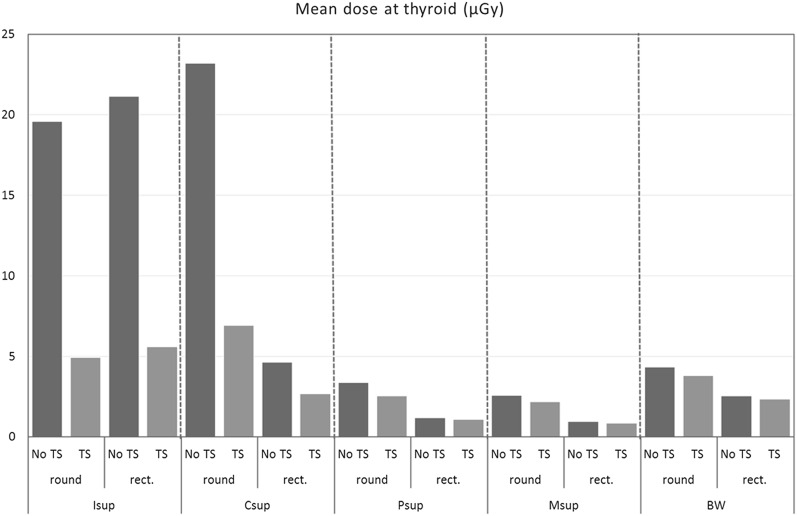

Mean doses at the site of the thyroid gland, corrected for exposure time and background radiation, for the four modalities are shown in Table 3 and Figure 3 The ANOVA test revealed that the thyroid shield reduced the dose in all modalities significantly (for all tests, p < 0.001). The greatest absolute and relative reductions were found for the Isup and Csup positions. For the Isup, thyroid dose levels were comparable with both collimators at a level indicating primary beam exposure. Thyroid shield reduced this dose with circa 75%. For the Csup position, round collimation also revealed primary beam exposure, and thyroid shield yield was 70%. In Csup with rectangular collimation, the thyroid dose was reduced with a factor 4 compared with round collimation, and the thyroid shield yielded an additional 42% dose reduction. Except for Isup, all dose measurements of rectangular collimation without thyroid shield were lower than those of round collimation with thyroid shield. When rectangular collimation was used for the upper bicuspid, Msup and BW, the use of thyroid shield reduced these already reduced dose levels by 10% or less.

Table 3.

Mean dose values of 10 measurements and their standard deviations and the percentage reduction achieved by thyroid shielding and its confidence interval for the 5 exposure geometries with round and rectangular (rect.) collimation

| Exposure geometry | Round or rectangular collimation | Thyroid shield | Mean dose at thyroid (µGy) | Standard deviation (µGy) | Significance (p-value) | Reduction by TS (%) | 95% CI (% reduction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isup | Round | No | 19.56 | 0.019 | – | ||

| Yes | 4.93 | 0.103 | <0.001 | 74.78 | (70.60–78.96) | ||

| Rect | No | 21.12 | 0.132 | – | |||

| Yes | 5.59 | 0.060 | <0.001 | 73.55 | (71.05–76.05) | ||

| Csup | Round | No | 23.17 | 0.187 | – | ||

| Yes | 6.90 | 0.053 | <0.001 | 70.24 | (68.00–72.48) | ||

| Rect | No | 4.63 | 0.025 | – | |||

| Yes | 2.68 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 42.17 | (39.71–44.63) | ||

| Psup | Round | No | 3.35 | 0.013 | – | ||

| Yes | 2.54 | 0.017 | <0.001 | 24.19 | (22.62–25.76) | ||

| Rect | No | 1.18 | 0.005 | – | |||

| Yes | 1.08 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 9.11 | (8.13–10.09) | ||

| Msup | Round | No | 2.57 | 0.015 | – | ||

| Yes | 2.16 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 16.05 | (14.71–17.39) | ||

| Rect | No | 0.95 | 0.004 | – | |||

| Yes | 0.86 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 10.04 | (7.39–12.69) | ||

| BW | Round | No | 4.32 | 0.009 | – | ||

| Yes | 3.80 | 0.023 | <0.001 | 20.00 | (18.71–21.29) | ||

| Rect | No | 2.52 | 0.010 | – | |||

| Yes | 2.32 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 7.86 | (6.85–8.87) |

BW, bitewing; CI, confidence interval; Csup, upper canine; Isup, upper incisor; Msup, upper molar; Psup, upper bicuspid; TS, thyroid shielding.

Figure 3.

Diagram of the mean dose level measured at the thyroid for the different geometries with round collimation and rectangular (rect.) collimation, with and without thyroid shielding (TS). BW: bitewing; Csup: upper canine; Isup: upper incisor; Msup: upper molar; Psup: upper bicuspid.

Discussion

During exposures of the upper anterior teeth, the area of the thyroid appears to be within the primary beam and dose levels are relatively high with both round collimation and rectangular collimation. In these instances, the use of thyroid shield reduces thyroid dose levels by circa 75%. As the thyroid is a very radiosensitive organ, the use of thyroid shield during exposure of the upper anterior area is to be recommended. As the direction of the X-rays with occlusal exposures is similar to that of the anterior periapical exposures, the use of thyroid shield with occlusal exposures can also be advised.

On the basis of the results in this study, it can be confirmed that the use of rectangular collimation without thyroid shield results in a large reduction of dose to the thyroid in comparison with round collimation. Except for Isup, all exposures with rectangular collimation without thyroid shield result in a lower thyroid dose than those with round collimation with thyroid shield. Thus, when comparing rectangular collimation or thyroid shield as dose reduction measures, it is clear that rectangular collimation is more potent for thyroid shielding. The thyroid shield augments substantially to this dose reduction of rectangular collimation for upper anterior and canine exposures. The thyroid shield reduces the thyroid dose for the other exposure geometries with rectangular collimation marginally by 10% or less, where the dose is already low.

In this study, an adult male phantom was used. Children have smaller body dimensions, and this results in less shielding from overlying tissues. Also, the shorter distance between the tube and the thyroid in children results in a higher thyroid dose following the inverse square law. This effect is amplified by the higher risk factor because the tissues of children are more radiosensitive than those of adults.17 This means the use of thyroid shield is even more important when exposing children.

In our experiment, we found that the use of thyroid shield with round collimation resulted in dose reductions that are comparable with those found in the literature.3–8 This indicates that our experimental setup with the survey detector at the location of the thyroid is valid for evaluating thyroid dose levels. It should be noted that our experimental setup is not identical to a dose study to calculate the effective dose of exposure modalities. Because in this article we focus on the dose to the thyroid gland, measurements were performed only at the location of the thyroid. This makes it possible to compare the thyroid dose from different exposure protocols. This way of measuring dose at a location does not facilitate the calculation of effective dose to the patient. For this purpose it would be necessary to perform measurements at multiple sites in the phantom. It is possible that the reduction of the thyroid dose levels is achieved at the expense of slightly elevated dose levels in other organs, as the use of the thyroid shield is expected to generate some stray radiation. This would lessen the yield of the thyroid shield. As stray radiation is only a small fraction of the primary beam, these elevations cannot be expected to be substantial. In this study design, we measured only at the site of the thyroid gland; therefore, this aspect cannot be quantified.

During our experimental exposures, there was no image receptor such as a phosphor plate, digital sensor or film present in the mouth of the phantom, as this is practically impossible in a RANDO phantom. This differs from the clinical situation because this image receptor attenuates a part of the image-forming beam and induces stray radiation. It can be assumed that a higher dose was measured at the level of the thyroid gland because of this, as is also the case in other dose studies. Because all exposures were performed without an image receptor, the comparison between the different exposure modalities is still valid.

The thyroid shield used in this study fitted tightly around the neck of the phantom. However, the material of the phantom is not compressible, contrary to the tissues of the neck of humans in the clinical situation. This means that the shield can be pressed more dorsal in vivo, which would probably result in a larger reduction of radiation of the thyroid.

The exposure times for round collimation and rectangular collimation recommended by the manufacturer differ by a Factor 2. This is to compensate for the longer focus–image receptor distance for rectangular collimation. The inverse square law implies that the dose decrease along the path of the beam from the image receptor to the location of the thyroid gland is less for the rectangular collimation. This is reflected in the higher dose measured at the thyroid location during Isup geometry with rectangular collimation than that with round collimation.

The dose to the thyroid is a combination of the primary beam and stray radiation that is generated by the primary beam in the tissues of the patient. With the more diverging beam of the round collimation when the thyroid gland is not in the primary beam, dose levels are higher because tissues closer to the thyroid gland are irradiated and produce stray radiation close to the thyroid gland. This explains the lower thyroid dose with rectangular collimation and the relative marginal effect of thyroid shielding, when the thyroid is not in the primary beam.

The as low as reasonably achievable principle is presented by the International Commission on Radiological Protection with the connotation “social and economic factors taken into account”.15 Using a thyroid shield reduces the dose at a certain cost. To assess if this investment is effective, a cost–utility analysis can be performed as proposed by Hoogeveen et al.18 When we assume the cost of the thyroid shield at €100 and the effective dose reduction of 50% or 1 µSv per exposure, then according to the referenced article, the thyroid shield would become cost effective in a high-income economy after circa 500 times of use. In offices with a younger patient population, this number would be substantially lower, as the radiation risks for younger people are two to three folds higher. This means that the use of thyroid shield can be seen as economically viable.

In conclusion, it can be stated that thyroid shield is a sensible dose-reducing measure when imaging upper anterior teeth, even when rectangular collimation is used. Practice guidelines should advise practitioners to utilize thyroid shield when imaging the upper anterior teeth; for children, this advice should be even more stringent.

Contributor Information

Reinier C Hoogeveen, Email: r.hoogeveen@acta.nl.

Bart Hazenoot, Email: bart3833@hotmail.com.

Gerard C H Sanderink, Email: g.sanderink@acta.nl.

W Erwin R Berkhout, Email: e.berkhout@acta.nl.

References

- 1.International Commission on Radiation Protection. 1977 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiation Protection, ICRP publication 26. Ann ICRP 1977; 1(3). [Google Scholar]

- 2.ICRP. The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP publication 103. Ann ICRP 2007; 37(2–4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Memon A, Godward S, Williams D, Siddique I, Al-Saleh K. Dental X-rays and the risk of thyroid cancer: a case-control study. Acta Oncol 2010; 49: 447–53. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02841861003705778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rush ER, Thompson NA. Dental radiography technique and equipment: how they influence the radiation dose received at the level of the thyroid gland. Radiography 2007; 13: 214–20. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2006.03.002 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludlow JB, Davies-Ludlow LE, White SC. Patient risk related to common dental radiographic examinations: the impact of 2007 International Commission on Radiological Protection recommendations regarding dose calculation. J Am Dent Assoc 2008; 139: 1237–43. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sikorski PA, Taylor KW. The effectiveness of the thyroid shield in dental radiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1984; 58: 225–36. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(84)90141-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitcher BL, Gratt BM, Sickles EA. Leaded shields for thyroid dose reduction in intraoral dental radiography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1979; 48: 567–70. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(79)90306-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaffe I, Littner MM, Shlezinger T, Segal P. Efficiency of the cervical lead shield during intraoral radiography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1986; 62: 732–6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(86)90272-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kircos LT, Angin LL, Lorton L. Order of magnitude dose reduction in intraoral radiography. J Am Dent Assoc 1987; 114: 344–7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1987.0085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt K, Velders XL, van Ginkel FC, van der Stelt PF. The use of a thyroid collar for intraoral radiography. [In Dutch.] Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd 1998; 105: 209–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Commission. European Guidelines on radiation protection in dental radiology: the safe use of radiographs in dental radiology. Radiation protection 136. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. The use of dental radiographs: update and recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc 2006; 137: 1304–12. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Council on Radiological Protection and Measurement. NCRP report No. 145, radiation protection in dentistry. Bethesda, MD: National Council on Radiological Protection and Measurement; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Thyroid Association. Policy statement on thyroid shielding during diagnostic medical and dental radiology. Falls Church, VA: American Thyroid Association; 2013. [Updated 28 March 2013; cited 10 November 2015.] Available from: http://www.thyroid.org/wp-content/uploads/statements/ABS1223_policy_statement.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gijbels F, Jacobs R, Bogaerts R, Debaveye D, Verlinden S, Sanderink G. Dosimetry of digital panoramic imaging. Part I: patient exposure. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2005; 34: 145–9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr/28107460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnold LV, Duinkerke ASH, Stelt van der PF. Dental radiography: handbook for dento maxillofacial radiology. [In Dutch]. Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands: Stafleu & Tholen; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Commission on Radiological Protection. 1990 recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection, Publication 60. Ann ICRP 1991; 21: 1–41. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0146-6453(91)90009-6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoogeveen RC, Sanderink GC, van der Stelt PF, Berkhout WE. Reducing an already low dental diagnostic X-ray dose: does it make sense? Comparison of three cost-utility analysis methods used to assess two dental dose-reduction measures. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2015; 44: 20150158. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20150158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]