Abbreviations

- cTnI

cardiac troponin I

- IFA

indirect fluorescent antibody

- TAMU‐VMTH

Texas A&M University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

A 10‐week old, intact male, Boxer puppy was referred to the Texas A&M University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (TAMU‐VMTH) for emergency evaluation of ascites secondary to right‐sided heart failure approximately 2 weeks after the owners purchased the dog from a breeder in south Texas. Clinical signs began 2 days before presentation, and included lethargy, acute inappetence, diarrhea, and vomiting that was nonresponsive to antiemetic therapy. At that time, the dog tested negative for parvovirus antigen. Abdominal and thoracic ultrasound examinations were performed and hepatomegaly, abdominal effusion, and enlarged right atrium and ventricle were reported. The dog presumptively was diagnosed with tricuspid valve dysplasia and was referred for further evaluation.

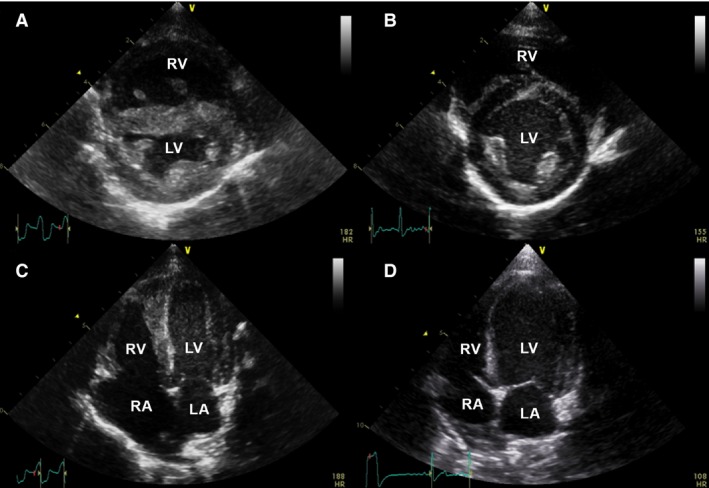

On presentation to the TAMU‐VMTH, the dog had dull mentation and was mildly tachypneic with a respiratory rate of 48 breaths/min, tachycardic with a heart rate of 240 beats/min, and had weak femoral pulses. Body condition score was 5/9 with a mildly distended abdomen that was soft on palpation. Brief abdominal ultrasound examination confirmed the presence of ascites. Indirect blood pressure measurement identified systemic hypotension with a systolic pressure of 43 mmHg and mean and diastolic pressures could not be obtained. Laboratory abnormalities included marked hyponatremia (127 mEq/L; reference range, 147–153 mEq/L), hyperkalemia (6.53 mEq/L; reference range, 3.91–4.4 mEq/L), hyperlactatemia (6.0 mmol/L; reference range, <2.5 mmol/L), mild hypocalcemia (1.16 mmol/L; reference range, 1.23–1.35 mmol/L), and a disproportionally increased BUN concentration (71 mg/dL; reference range, 7–32 mg/dL) compared to serum creatinine concentration (1.8 mg/dL; reference range, 0.2–2.5 mg/dL). An ECG disclosed a wide complex tachycardia that was unresponsive to several IV bolus injections of lidocaine. A standard transthoracic 2‐dimensional and Doppler echocardiographic study was performed with a phased‐array 2.7–8.0 MHz transducer.1 The right atrium and ventricle were severely dilated (Fig 1A, C) and ventricular systolic function was decreased (Video S1). The tricuspid valve leaflets were normal in appearance with mild tricuspid valve regurgitation noted. Mild pleural effusion was noted. Shortly after presentation, the dog died suddenly and a complete necropsy was performed.

Figure 1.

Echocardiographic images of the index puppy (A, C) and littermate #1 (B, D) for comparison purposes. Images from the right parasternal short axis view document normal ventricular chamber size for littermate #1 (B) compared to the index puppy where the right ventricle (RV) is severely dilated and a wide complex tachycardia is noted on the simultaneous ECG (A). Images from the left apical 4 chamber view document normal chamber size in littermate #1 and an ectopic beat on simultaneous ECG (D) compared to the index puppy where the right atrium (RA) is severely dilated (C, also depicted in the online version as Video S1). LA, left atrium, LV, left ventricle.

On gross evaluation of the heart, the right atrium was enlarged and there was marked, diffuse myocardial pallor of both ventricles (Fig 2A). The tricuspid valve was structurally normal. Histology of the heart disclosed severe lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic necrotizing pancarditis affecting the atria (Fig 3A) and ventricles (Fig 3C, E) with resultant cardiomyocyte degeneration and necrosis. Numerous cardiomyocytes had protozoal pseudocysts containing amastigotes (Fig 4A) with parallel kinetoplasts. Based on the presence of severe myocarditis and amastigotes, a preliminary diagnosis of Chagas disease was made. Additional relevant findings included acute centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis, pulmonary edema, and mild meningoencephalitis with a single macrophage containing intracytoplasmic amastigotes.

Figure 2.

Hearts from both puppies that died suddenly depicting marked myocardial changes observed for the index puppy (A) and littermate #3 (B). Both puppies had diffusely pale, mottled myocardium. Right atrial (RA) enlargement can be appreciated in littermate #3.

Figure 3.

Representative histologic images of lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic necrotizing pancarditis affecting the right atria (A and B), right ventricles (C and D), and left ventricles (E and F) of the index puppy (A, C, E) and littermate #3 (B, D, F). The myocardial inflammation is generally similar between the puppies, both in cellular composition and severity with few normal cardiomyocytes remaining in all sections. A fibrinocellular thrombus (*) can be observed within the right atrial lumen of the index puppy (A). 4× (insert magnification is 40×), H&E. RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle.

Figure 4.

(A) Histopathology of the myocardium in the index puppy documenting myocardial inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages; which was similar in composition for both affected puppies. In this field, cardiomyocytes have loss of cross striations, hypereosinophilia, and loss of nuclear detail indicative of degeneration and necrosis, and are separated by clear space (edema). Also present are four pseudocysts filled with amastigotes (arrowheads), as well as a few degenerate neutrophils infiltrating an infected, necrotic cardiomyocyte (arrow), 40×, H&E. (B–D) Histopathology from littermate #3 illustrating (B) a cardiomyocyte containing a pseudocyst with numerous amastigotes (arrowheads) 60×, H&E; (C) a focal area of necrosis and lymphohistiocytic inflammation within the liver and a macrophage filled with intracytoplasmic amastigotes (arrowhead) 40×, H&E; (D) diffuse, marked lymphoid hyperplasia of the spleen as well as occasional macrophages filled with amastigotes (arrowhead) 60×, H&E.

The breeder was contacted and reported that the remaining 6 littermates and dam were alive and had not exhibited any abnormal clinical signs. Three of the puppies from the litter and the dam were evaluated for Chagas disease at the TAMU‐VMTH the following week. All 4 dogs had normal physical examination findings and body condition scores, and the puppies all were similar in size. Each dog had an indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test2 for Trypanosoma cruzi, serum cardiac troponin I (cTnI) concentration using a high‐sensitivity immunoassay,3 complete transthoracic echocardiographic study, and a 5‐minute multi‐lead ECG performed. Premortem Chagas IFA titer and cTnI were not obtained from the index puppy.

Chagas IFA test results were negative (<1:20 dilution) for the dam and 3 littermates. Serum concentrations of cTnI were above the lower detection limit of 0.006 ng/mL in all 4 dogs with a mean of 0.271 ng/mL (range, 0.066–0.847 ng/mL), and in 1 dog the serum cTnI concentration was above the reference range for healthy dogs of 0.006–0.128 ng/mL reported for this assay.1 The dam did not have any abnormalities noted on 5‐minute ECG or echocardiography and serum cTnI concentration was 0.073 ng/mL. Littermate #1 did not have any abnormalities noted on 5‐minute ECG and serum cTnI concentration was 0.096 ng/mL. The heart appeared structurally normal on echocardiography (Fig 1B, D). During the echocardiogram, the puppy had ventricular ectopy characterized as a single ventricular premature complex and 2 escape beats. Littermate #2 did not have any abnormalities noted on 5‐minute ECG and serum cTnI concentration was 0.066 ng/mL. Subjective mild enlargement of the right ventricle was present compared to the littermates, and the remainder of the echocardiogram was normal. Littermate #3 did not have any abnormalities on 5‐minute ECG or echocardiography, and serum cTnI concentration was 0.847 ng/mL.

Approximately 2 weeks after clinical evaluation, littermate #3 became acutely lethargic and died suddenly at home. A complete necropsy was performed. Gross evaluation of the heart disclosed similar findings to the index puppy with severe, diffuse myocardial pallor of all chambers (Fig 2B). Histology identified severe lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic necrotizing pancarditis affecting both atria (Fig 3B) and ventricles (Fig 3D, F). Numerous cardiomyocytes contained pseudocysts filled with amastigotes (Fig 4B). Similar to the first puppy, pulmonary edema and acute centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis were evident. Additionally, lymphohistiocytic inflammation in the liver and marked lymphoid hyperplasia of the spleen also were seen along with infrequent macrophages infiltrated with intracytoplasmic amastigotes (Fig 4C, D). The presence of T. cruzi within myocardial tissue was confirmed using a conventional PCR to target kinetoplast minicircle DNA2 and a quantitative, real‐time PCR to target satellite DNA.3 The discrete taxonomic unit of the parasite from both affected dogs was characterized as T. cruzi type I (TcI).4

One month after the puppies were evaluated, a Chagas IFA titer was re‐evaluated by the local veterinarian in the surviving littermates (#1 and #2) and remained negative (<1:20). The cTnI concentrations, echocardiograms and ECGs were not re‐evaluated at that time. According to the breeder, the dogs were alive and doing well 21 months (littermate #2) and 30 months (dam and littermate #1) after the initial evaluation. The dam had another litter of puppies 6 months after initial evaluation at TAMU‐VMTH. None of these dogs reportedly had overt clinical manifestations of Chagas myocarditis.

Chagas disease is a cause of myocarditis in humans and dogs in Latin America and may be an under‐recognized cause of myocarditis in the southern United States.5 It is caused by the protozoan parasite, T. cruzi, and is transmitted by an infected insect vector, the triatomine bug.5, 6, 7, 8 Transmission by the triatomine bug occurs when feces from the hindgut of the insect, infected with the metacyclic trypomastigote stage of the parasite, is ingested or comes into contact with an open wound or mucous membranes.6, 8 Blood contact (transfusion or accidental inoculation) has been reported in humans, and transplacental and transmammary transmission have been reported in humans and dogs.6, 7, 8 After infection, trypomastigotes circulate within the bloodstream and also can enter macrophages, disseminating throughout the body. Trypomastigotes have been reported to be detectable in blood by cytology as early as 3 days after experimental infection in dogs.9 Peak parasitemia in dogs occurs at approximately 17 days after infection, when signs of generalized lymphadenopathy and acute myocarditis may develop.6 In dogs, parasites are found primarily in the myocardium but have been isolated from the brain, lymph node, cerebrospinal fluid, liver, spleen, stomach, small intestine, esophagus, and adrenal gland.5, 10 Approximately 14 days after infection, the parasites reach the tissues and develop into amastigotes, the intracellular form.6 The amastigotes continue to multiply and form pseudocysts within cardiomyocytes causing an inflammatory response that results in arrhythmias, cardiac chamber dilatation, and systolic dysfunction.6, 7, 8, 10

Diagnostic test results can vary depending on the stage of disease and possibly the T. cruzi strain.11, 12 Reported ECG findings depend on location, severity, and chronicity of myocardial infiltration and include bradyarrhythmias, sinus nodal dysfunction, atrioventricular block, bundle branch block, and sustained and nonsustained ventricular and atrial tachyarrhythmias.13 Echocardiographic findings also vary greatly and may be normal in acutely or mildly affected dogs, whereas chronically and severely infected dogs can have marked ventricular and atrial enlargement as well as myocardial functional impairment.10, 14, 15 Parasite strain type may influence antibody response and infectivity, and specific strains are associated with acute and chronic Chagas disease in different regions of Latin America.16 The TcI strain that was found to infect both puppies in this report is the predominant infective strain identified in humans in Latin America and has been reported in humans and mammals in North America.17

Transplacental or transmammary transmission was considered unlikely in the puppies in this report based on the serial negative Chagas IFA test results in the dam and in the surviving littermates, as well as the lack of clinical signs in the second litter from the dam. The most plausible route of infection for the puppies was contact with infected feces from insect vectors or ingestion of the vector as the dogs were from a Chagas endemic area,5 and had access to the outdoors. Furthermore, the breeder reported that she collected triatomine insects in the environment. The puppies died between the end of August and the end of September, coinciding with the summer to fall activity period of triatome insects in Texas.18 Although the oral transmission route has not been studied in dogs, human patients who are infected by oral transmission are reported to have a higher incidence of myocarditis and higher mortality rate.8

The wide complex tachycardia seen in the first puppy was nonresponsive to lidocaine and there were no discernable P waves, which may have represented a wide complex supraventricular tachycardia, bundle branch block or a sustained ventricular tachycardia nonresponsive to therapy. These rhythms have been previously reported in dogs with Chagas myocarditis.14 The tachyarrhythmia and history of a young dog from a Chagas endemic area in Texas with frequent access to outdoors,5 combined with echocardiographic findings of right heart enlargement and systolic dysfunction, increased the clinical suspicion of Chagas disease and are consistent with previous reports of young dogs being more severely affected.6, 14 Although serum was not available to perform a Chagas IFA test before the index puppy's death, the diagnosis was confirmed by histopathology and PCR.

Littermate #3 did not have any identifiable abnormalities on ECG or echocardiography and an IFA test was negative. The dog, however, died with severe pancarditis and abundant parasite pseudocysts in the heart 2 weeks later. Our report indicates that available diagnostic screening tests, including antibody detection, may not be useful for detecting infection in acutely infected or asymptomatic dogs. The negative IFA test results in the puppies in this report likely are related to low or absent antibody concentrations associated with acute infection, similar to negative tests in humans with acute infection with Chagas disease.8 Littermate #3 had the highest serum cTnI concentration (0.847 ng/mL), suggesting that analysis of serum cTnI concentrations should be considered in identifying acute myocarditis in dogs with Chagas disease. A cause for the detectable serum cTnI concentration in the dam and littermates (#1 and #2) was not identified, and results may have been normal based on concentrations that were within the range reported for healthy dogs.1

Echocardiographic and ECG evaluations also were not sensitive in littermate #3, which is consistent with a previous report of dogs experimentally inoculated with T. cruzi lacking significant changes in these tests after acute infection.15 The poor sensitivity of these tests cannot be understated because gross necropsy and histology findings documented severe systemic infection, supported by the findings of marked inflammation within the heart, spleen, intestines, lymph nodes and liver and presence of amastigotes within the myocardium and macrophages in the liver and spleen as well as parasite DNA in the heart. In symptomatic dogs with advanced disease, echocardiographic indices and ECG appear to be useful tools to aid in the diagnosis of Chagas disease.

We consider Chagas myocarditis a differential diagnosis in dogs that live or have traveled to a Chagas endemic area (e.g., southern United States, and Latin America5) and have brady‐ or tachy‐arrhythmias, ventricular dilatation with decreased systolic function, especially of the right ventricle in young dogs, or are littermates or housemates of infected dogs.19 Although there is no current consensus on treatment for Chagas disease in dogs, diagnosis of this disease has an important clinical implication for long‐term prognosis. Data on effective treatment for Chagas infection in dogs are lacking and treatment is aimed at management of disease manifestations including pharmacologic treatment of ventricular arrhythmias with class III drugs, medical management of heart failure, and pacemaker implantation for severe bradyarrhythmias.20, 21 Not all humans or dogs infected with T. cruzi will develop clinical manifestations of the disease. In asymptomatic patients that test positive for Chagas disease using IFA testing, screening dogs with an ECG and echocardiogram with periodic follow‐up is recommended.

This report highlights the diagnostic challenges encountered with acute Chagas infection in dogs. Cardiac troponin I may be an early marker of parasitic myocarditis.

Parasite strain typing also may be of additional benefit in the future because different strains may result in variable clinical responses. Furthermore, the diagnosis of Chagas disease in dogs also may have human health implications because infected vectors in the environment may pose a risk for human transmission. Client education therefore should focus on increasing awareness of the vector and environmental risk factors.6, 8

Supporting information

Video S1. Echocardiographic image obtained from the left apical 4 chamber view from the index puppy documenting right‐sided cardiomegaly and ventricular dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kathy Glaze, Jill VanWhy, Rachel Curtis‐Robles, and Lisa Auckland for technical assistance, and Scott Birch for assistance with figure and video preparation.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

All work performed at Texas A&M University.

Footnotes

GE Vivid E9, GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Horton, Norway

Canine Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas) IFA, Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory, College Station, TX

Advia Centaur TnI‐Ultra, Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, New York, NY

References

- 1. Winter RL, Saunders AB, Gordon SG, et al. Analytical validation and clinical evaluation of a commercially available high‐sensitivity immunoassay for the measurement of troponin I in humans for use in dogs. J Vet Cardiol 2014;16:81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Virreira M, Torrico F, Truyens C, et al. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction methods for reliable and easy detection of congenital Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003;68:574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Duffy T, Cura CI, Ramirez JC, et al. Analytical performance of a multiplex real‐time PCR assay using TaqMan probes for quantification of Trypanosoma cruzi satellite DNA in blood samples. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7:e2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Souto RP, Fernandes O, Macedo AM, et al. DNA markers define two major phylogenetic lineages of Trypanosoma cruzi . Mol Biochem Parasitol 1996;83:141–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kjos SA, Snowden KF, Craig TM, et al. Distribution and characterization of canine Chagas disease in Texas. Vet Parasitol 2008;152:249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barr SC. Canine chagas’ disease (American Trypanosomiasis) in North America. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2009;39:1055–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Malik LH, Singh GD, Amsterdam EA. Chagas heart disease: An update. Am J Med 2015;128:1251.e7–1251.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bern C. Chagas’ disease. N Engl J Med 2015;373:456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barr SC, Gossett KA, Klei TR. Clinical, clinicopathologic, and parasitologic observations of trypanosomiasis in dogs infected with North American Trypanosoma cruzi isolates. Am J Vet Res 1991;52:954–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barr SC, Simpson RM, Schmidt SP, et al. Chronic dilatative myocarditis caused by Trypanosoma cruzi in two dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1989;195:1237–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nogueira‐Paiva NC, Fonseca KdS, Vieira PMdA, et al. Myenteric plexus is differentially affected by infection with distinct Trypanosoma cruzi strains in Beagle dogs. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2014;109:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barr S, Baker D, Markovits J. Trypanosomiasis and laryngeal paralysis in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986;188:1307–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elizari MV, Chiale PA. Cardiac arrhythmias in Chagas’ heart disease. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1993;4:596–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meurs KM, Anthony MA, Slater M, et al. Chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection in dogs: 11 cases (1987–1996). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;213:497–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barr SC, Holmes RA, Klei TR. Electrocardiographic and echocardiographic features of trypanosomiasis in dogs inoculated with North American Trypanosoma cruzi isolates. Am J Vet Res 1992;53:521–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Santana RAG, Magalhães LKC, Magalhães LKC, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi strain TcI is associated with chronic Chagas disease in the Brazilian Amazon. Parasit Vectors 2014;7:267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bern C, Kjos S, Yabsley MJ, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas’ disease in the United States. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:655–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Curtis‐Robles R, Wozniak EJ, Auckland LD, et al. Combining public health education and disease ecology research: Using citizen science to assess Chagas disease entomological risk in Texas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:1–12. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tenney TD, Curtis‐Robles R, Snowden KF, et al. Shelter dogs as sentinels for Trypanosoma cruzi transmission across Texas. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:1323–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dubner S, Schapachnik E, Riera ARP, et al. Chagas disease: State‐of‐the‐art of diagnosis and management. Cardiol J 2008;15:493–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saunders AB, Gordon SG, Rector MH, et al. Bradyarrhythmias and pacemaker therapy in dogs with Chagas disease. J Vet Intern Med 2013;27:890–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video S1. Echocardiographic image obtained from the left apical 4 chamber view from the index puppy documenting right‐sided cardiomegaly and ventricular dysfunction.