Abstract

To upgrade nursing instruction capacity in Cambodia, two bridging programmes were opened for the Bachelor of Science in Nursing simultaneously in‐country and out‐of‐country (Thailand). A descriptive qualitative study was conducted to assess effectiveness of both programmes jointly and to explore needs concerning the further development of nursing education. This study included interviews with 34 current or previous programme participants (nursing instructors or hospital preceptors) and 10 managers of collaborating institutions. New learning content, personal outcomes, challenges and obstacles and future needs were qualitatively coded to create categories and subcategories of data. Findings show that programme participants were most influenced by the new content areas (e.g. nursing theory and professionalism), active teaching–learning strategies and the full‐time educational immersion afforded by the out‐of‐country programme. Programme participants who had returned to their workplaces also identified on‐going needs for employing new active teaching–learning approaches, curriculum revision, national standardization of nursing curricula and improvements in the teaching–learning infrastructure. Another outcome of this study is the development of a theoretical model for Nursing Capacity Building in Developing Countries that describes the need for intermediate and long‐term planning as well as using both Bottom‐Up and Edge‐Pulling strategies.

Keywords: bottom‐up strategies, Cambodia, capacity building, edge‐pulling strategies, faculty development, health manpower

Introduction

Since the 1990s, the Cambodian Ministry of Health (MoH) has adjusted its focus from an acute care model to address the acute health personnel shortages by tackling quantity and quality issues via policy development and planning.1, 2 Despite this effort, a substantial health personnel shortage remains; Cambodia has the lowest staffing levels, with 0.2 doctors and 0.9 nurses and midwives per 1000 population.3 Cambodia also has the greatest subnational inequalities in the distribution of doctors, which affects task sharing and role substitution among nurses, other co‐medicals and families. Consequently, nurses and midwives, who account for 44.7% and 25% of the health workforce respectively,4 focus on medical interventions rather than nursing services.5

Improvements in nursing and midwifery education are recognized as essential in increasing workforce numbers and enhancing the quality of health care and health systems.6, 7 To improve the quality and quantity of nursing care in Cambodia, it is necessary to increase the number of nursing instructors who have both expertise in nursing care and commensurate education. In Cambodia, history has played a part in the deficit of adequately prepared nursing faculty; very few health professionals survived the civil war (1975–1979).1 Among the 362 nursing faculty in Cambodia today,8 barely 20% (n = 71) hold bachelor's degrees; the sources of these degrees were the bridging programmes described in this report. This represents a severe shortage. For example, one such programme, initiated in 2009, lacks qualified instructors in spite of an enrolment of 808 in 2014.9 This is in spite of an increase in nursing schools from just six public schools in 2009 and an additional 11 private schools by 2014.8, 9

In spite of this increase in basic nursing programmes, most nursing and midwifery instructors only hold associate degrees or equivalent qualifications, and the number with bachelor's degrees is limited.8 However, Cambodia is not different from other developing countries with common underlying challenges such as teaching staff shortages at the primary and secondary school levels. Nursing programmes also suffer from a lack of institutional resources for teaching clinical skills, insufficient continuing development of faculty members, and weak collaborative linkages between clinical and educational institutions.3, 7 In spite of these types of difficulties, nursing education in other countries (India, Sri Lanka and Sub‐Saharan Africa) has overcome similar challenges through collaborative faculty development programmes.7, 10, 11, 12

This evaluation report focuses on two bridging programmes that were initiated in 2011 to allow current faculty members to upgrade to a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN). Because the Cambodian MoH organized the programmes, only individuals who were public servants were allowed to participate.13 Both BSN programmes included both instructors from schools of nursing and clinical preceptors from collaborating clinical agencies. Including both groups in this capacity building effort was designed to improve instruction and nursing student outcomes within nursing schools and in clinical teaching sites.

One programme was a 47‐credit, 24‐month programme offered with the support of faculty members from the University of Philippines, Manila.13 This programme was offered in the capital city, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; classes were taught by visiting faculty over one full week each month. These students otherwise remained full‐time employees the other weeks in the month. That is, they maintained family and work‐related duties in addition to their studies. Almost half of these students travelled from rural areas to attend classes. The second programme was a 78‐credit, 18‐month BSN programme offered on‐campus at Saint Louis College of Nursing in Bangkok, Thailand. This programme included a transferred credit system accredited by the Thai Ministry of Education. Students in this programme attended classes on campus, had access to the university's teaching–learning resources and completed clinical experiences in Thailand.13

This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of these two bridging programmes by examining the following: new nursing content areas, personal outcomes of programme participants, institutional outcomes, personal challenges and obstacles encountered during and after the programmes and developmental needs of the nursing educators after graduation when they returned to full‐time work. This programme evaluation was designed to both provide feedback to collaborating educational, health care and funding agencies and to facilitate further strategic planning in health workforce development at the national level.

Methods

Sample

The sample included two different groups of subjects. The first consisted of the nursing or midwifery instructors and clinical preceptors who were current or previous students in either bridging programme. These individuals were selected based on their availability and were recommended by the MoH. The second group consisted of managers of participating agencies including school directors, technical bureau chiefs, hospital directors and nursing directors. This second group was selected to generate data regarding institutional changes, attitudes or events that evolved after programme participants returned to the workplace. Subjects were interviewed individually or in groups according to availability.

Data collection

Semi‐structured interviews were conducted between in late August 2014. An interview guide was developed to identify the following: motivation to participate the programme; main lessons learned during the programme; expectations at completion of the programme; support received at their working place, gaps between expectation and reality; personal obstacles encountered, personal achievements or contribution to their institution after graduation; contribution to nursing profession in Cambodia and suggestions and requests for further utilization of their new qualifications. Researchers conducted interviews via a native bilingual interpreter.

Data analysis

An individual who understood both English and Khmer dictated subjects' responses during the live interviews. Data from each group or individual interview were transcribed into English for analysis. In accordance with qualitative descriptive method, phrases that corresponded to programme participants' main lessons learned, outcomes, challenges and obstacles during and after the programme, and needs for further development were extracted, coded and reviewed repeatedly. Categories and subcategories developed until saturation occurred as determined by the investigators. The managers' expectations, reports observable outcomes by graduates and needs for the further faculty development were used in the triangulation of programme participants' views.

Ethical considerations

This research was part of a Japan–Cambodia bilateral cooperation entitled The Project for Strengthening Human Resource Development System of Co‐medicals in Cambodia funded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency. The Cambodian MoH approved the research. The study purpose and potential subject's right to decline participation were explained to all individual who were interviewed. All participants provided oral informed consent. Interviews were dictated without notation of the speaker's identity.

Results

Between 2011 and 2014, 29 nursing instructors were enrolled in the BSN programme in Cambodia and 32 nursing or midwifery instructors and clinical preceptors completed the programme in Thailand. The study sample consisted of 34 programme participants from the two bridging programmes. Subjects included nearly half (n = 14, 48.3%) of those from the in‐country programme and nearly two‐thirds (n = 20, 62.5%) of those who studied in Thailand. Ten managers from eight cooperating institutions in Cambodia were also interviewed. Table 1 shows the programme participants' demographic information. The participants from the in‐country programme had an average of 5.8 years more teaching experience than those who attended the residential programme in Thailand. There was no difference in mean ages between students in the two programmes (Cambodia: 37.5 ± 5.7 years and Thailand: 40.8 ± 7.9 years). Text box 1, 2 and 3 contains a summary of the main lessons learned, programme participants' outcomes, challenges and obstacles that were revealed in analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of participants

| Demographic characteristics | Out‐country (n = 20) | In‐country (n = 14) | Total (n = 34) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (range) | 37.5 (29–47) | 40.8 (30–54) | 37.5 (29–54) |

| Sex: Male | 10 (50.0%) | 9 (64.3%) | 19 (55.9%) |

| Teaching experience* | |||

| Average (years) | 8.8 | 14.6 | 11.8 |

| Less than 5 | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (14.3%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| 6–10 | 4 (44.4%) | 5 (35.7%) | 9 (39.1%) |

| 11–20 | 3 (33.3%) | 2 (14.3%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| More than 21 | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (35.7%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Total | 9 | 14 | 23 |

Nursing teachers only.

New nursing content areas

Upgrading expertise

Programme participants mastered new content areas that included newborn care, geriatric nursing and community nursing, mental health care, holistic care, caring, statistics, management and economics, nursing informatics and nursing education. They also gained expertise in using informatics in searching for information and conveying this knowledge and skills to students. An important outcome reported was improved self‐confidence.

Box 1 – Main lessons learned (New nursing content areas):

Upgrading expertise

Upgraded knowledge and skills

New subjects and concepts

Students evaluation

Information search by oneself

Self‐confidence as a nurse

New approaches in teaching

Teaching methods/styles

Methods of practicum design

Transforming theory into practice

Application of nursing process in practice

Nursing care and education models

Experience of quality nursing care and health system

Concept of Nursing

Ideal teacher

New teaching approaches—transforming theory into practice

Programme participants were exposed to a teaching style described as ‘student‐centred,’ which was a new approach for them. Concerning clinical practicum approaches, case‐based practice was highlighted over skill‐based practice, which still prevails in Cambodia. Subjects also recognized the importance of the link between theory and practice in nursing care. Programme participants' comments regarding nursing process provided an example of their understanding of transforming theory into practice.

I was surprised when I saw [the] nursing process in Thailand. They practiced it everywhere, even in [the] community. They applied it to actual situations.

Nursing care and education models

The curriculum also exposed programme participants to a variety of nursing care models. In addition, they were impressed that nursing instructors could serve as role models.

Nursing care is not only [the] provision of medicine but also helps patients to get better both mentally and physically. It is [a] nurse's role.

I found that nursing is more beautiful than that I thought before the study.

Observable outcomes

Application and dissemination of new knowledge

Programme participants were keen to apply knowledge and skills acquired during the programme. For example, managers noted the following; new lecturer methods, new strategies for evaluation of students' learning, advanced nursing process and management approaches in hospitals and introduction of case‐based clinical practicum using the nursing process in schools and hospitals.

Box 2 – Course attendants' observable outcomes:

Application of new knowledge to own work

Apply nursing process

Make changes in daily management of patients and nursing care

Improve supervision of students' clinical practice

Discipline students

Dissemination of new knowledge

Provide new and improved lessons with upgraded knowledge

Apply new teaching methods and styles

Improve clinical practicum style

Improve student evaluation

Involvement in improving teaching‐learning activities

Improve course syllabi and lesson plans

Contribution to the Cambodian nursing profession

Formulation of core group

Increased professionalism postgraduation

Aside from individual efforts at work, some graduates became engaged in a nationwide effort to standardize course syllabi. Technical support for this activity was also provided by the MoH and Japan International Cooperation Agency project. In addition, some programme participants have delivered presentations at nursing and medical conferences, and others prepared a legislative framework under the Cambodian Nursing Council. The graduates have also formed groups to lead strategic improvements in nursing education in Cambodia.

Challenges and obstacles

Individual obstacles

Some participants reported facing difficulties and obstacles in realizing their personal goals in the programmes. In particular, in‐country programme attendants had to complete lessons on a monthly schedule while they were still employed. The participants also had to continue to meet family obligations during the programme.

Box 3 – Challenge and obstacles:

Individual obstacles

Difficulty in catching up lessons

Inadequate environment

Lack of latest references in Khmer

Lack of computer skill of nursing school students

Lack of staff who understands well about new concepts and methods

Difference in expectations between BSN‐degree holders and managers

Difference in expectation between BSN holders and managers

Lack of support from colleagues

Overloaded

Lack of recognition of the nursing profession

Struggle in gaining understanding of other professions

Environmental factors

Participants reported that they had become acutely aware of the inadequate teaching–learning environments in Cambodia and listed this as a major obstacle to apply what they had learned. For example, nursing school libraries lack up‐to‐date references in local languages, students have poor computer skills and other staff members do not welcome or understand new concepts and methods. The lack of nursing books and journals were noted as a serious issue. Participants reported that this deficit prevents students from learning independently and hampered instructors when preparing lessons.

Difference in expectations

There were differences in expectations concerning the bridging programme outcomes between participants and their managers and colleagues. Some participants experienced difficulty, stress and frustration in making their new knowledge and skills understood and then being accepted. Other faculty often disagreed with their new strategies and ideas concerning improvement of teaching–learning activities.

Only a few staff agree with my ideas [for change]. For older staff, they think [they] have enough knowledge and [are] not willing to learn from me.

Lack of recognition of the nursing profession

Participants gained a new awareness of nursing as an independent profession and attempted to assume new responsibilities according to the models they had learned. However, they faced many challenges and difficulties concerning other medical professionals' failure to recognize the nursing as a unique profession.

Perspectives on the further development

Text box 4 contains a summary of participants and their managers' perspectives on professional development needs. Their ideas concerning further professional development were summarized as follows: strengthening human resources, updating teaching‐learning content and improving teaching–learning environments.

Box 4 – Perspectives on the further development:

Strengthening human resources

Continuous learning opportunities (upgrading course and in‐service training)

Improving of management and leadership skills

Exchanging experiences to ensure mutual development

Autonomy in nursing profession

Updating teaching‐learning activities

Curriculum revision

Improving teaching‐learning environments

Upgrading environments facilitates (i.e. infrastructure and equipment such as simulator) the application of course attendants' capacity

Strengthening human resources

Specialty practice areas and improving management and leadership

Participants identified the need to deepen speciality knowledge regarding specific nursing fields (e.g. paediatric and community health nursing) and improved teaching methodologies via continuous learning opportunities. Managers also noted that strengthening content in management and leadership was as a key issue at the institutional level.

As participants completed their clinical practicums they became aware that a theory–practice gap was evident between how nursing was delivered in Cambodia and what they had learned. Those who completed their studies in‐country noted that they did not have an opportunity to observe more advanced models of nursing care. They reported that this type of experience would be particularly beneficial.

Study tours to neighbouring countries and exchange programs between schools, these make us challenge ourselves to improve the quality of nursing in Cambodia to meet standards or compete in this region.

Recognizing mutual development and autonomy in nursing

Participants expressed a need for autonomy in nursing and wished to continue sharing their recent growth experiences as evolving nursing leaders in Cambodia. However, these development activities often require managerial support or policy changes to allow nurses to hold responsible positions in schools, hospitals and the Ministry. Participants reported having a new professional identity of nursing that has led them to create networks among other BSN nurses.

Graduates felt lonely after the completion of the program. To stay connected, we formed a graduate group and plan to include graduates from other upgrading programs.

Updating teaching–learning activities

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations developed an initiative called the Mutual Recognition Arrangement on Nursing Services to facilitate free movement of professional and skilled labour among member countries. 14 Therefore, curriculum revision and improvement in teaching–learning materials were identified as essential in meeting international standards of nursing competency.

Education in both schools and hospitals should be consistent and at a level equal to [those of] neighbouring countries. Because there are few BSNs, we want to raise the value of [the] BSN.

Improving teaching–learning environments

Upgrading instructional environments and nursing capacity

In spite of upgrading personnel and improving curriculum to address theory–practice gap, teaching–learning infrastructures must also be upgraded to match current standards and practice. This includes physical facilities and school equipment such as developing simulation labs for pre‐clinical teaching, computer laboratories and library resources.

Discussion

Programme effectiveness

The participants who were nursing instructors reported that their BSN experience made them acutely aware of the rigid and limited teaching styles used in their home institutions. They were impressed and motivated by the active teaching methods they experienced in their BSN programmes. The participants reported several key aspects of their educational experience including a student‐centred teaching–learning environment, using case‐based practicums to narrow the theory and practice gap and using role models in teaching nursing. For example, having interactive lectures with group work or self‐study using library reference materials or the Internet were reported by graduates as novel and effective teaching approachs.7, 11 These strategies differ from the prevailing teaching and learning methods in Cambodia that involve classical, one‐way, lecture‐based teaching without textbooks that prevents independent learning.8 Graduates also noted a lack of communication and coordination between educational and clinical practice settings and a discrepancy between what is taught in classrooms and observed in clinical nursing.8 Participants also identified the importance of being consistent in teaching and in clinical areas; case‐based teaching should follow through to clinical practicums. These findings illustrate a significant improvement in capacity and motivation. These results are also compatible with other reports of the impact of overseas educational experience, particularly the importance of collaboration between education and clinical practice.7 Further, because some instructors had insufficient clinical backgrounds,15 exposure to model nursing care was critical experience from an adult learning perspective.16 This type of learning experience allowed instructors to teach from ‘real’ nursing experience. Because direct patient care is often shared with family members,5 nursing faculty must be credible nurses themselves to teach and supervise students and family members about providing patient care.

In addition, participants felt that they were changed through their educational experiences and came to recognize their own professional identities.10 Furthermore, earning the BSN degree has opened other doors. For example, some have chosen to enrol in a master's degree in education for health professionals that was newly organized in Cambodia.13 Thus, it is likely that advanced degrees will enable them to seek other leadership roles in nursing education in the near future.

Participants also noted that the BSN programmes were offered in English, which has contributed to their individual capacity and increased their confidence.17 English proficiency is an important skill in countries like Cambodia because teaching materials and up‐to‐date information in the national language remain limited.13 For those who studied in Thailand, they reported that exposure to a different health‐care system with an explicit focus on nurse‐based primary care was particularly beneficial. It made the subsequent application of their learning realistic and clarified their understanding of deficits in teaching and practice in Cambodia.4

The data also revealed that follow‐up and support after participants graduated are crucial to help the instructors actualize what they have learned. Faculty development is known to work best when faculty members receive long‐term support via a mentorship system designed to enhance personal development.7, 18 Graduates found that transferring new knowledge and skills back at their prior work places required patience. Managers described being shocked when graduates wanted to apply their new knowledge right away, even though the environment was not ready. The graduates reported that they often relied on support from other graduates and that managerial support was crucial to maintaining motivation.18, 19 Fortunately, managers recognized this and gave them opportunities to organize meetings and workshops to disseminate their new knowledge. It is also noteworthy that many BSN graduates have promoted to managerial positions following a period of supervision.

However, graduates also noted substantial difficulties such as inadequate teaching–learning environments, a lack of cooperation and understanding by colleagues and managers because of differences in expectations and failure by others to recognize the scope of the nursing profession. Even though the instructors obtained a BSN degree, this did not ensure a leading role in improving teaching–learning activities. The graduates noted that in some situations there was a lack of preplanning between themselves, participating institutions, recipient institutions and the MoH. Some agencies had not clarified the expectations, roles and responsibilities of the participants after earning the degree that would allow them to make significant contributions afterwards. This phenomenon has also been observed in other studies.18, 19 Thus, careful planning and follow‐up at the institutional level should include modifying teaching assignments, membership in curriculum committees and infrastructure planning would be important to ensure optimal outcomes.

A Model—Nursing Capacity Building in Developing Countries

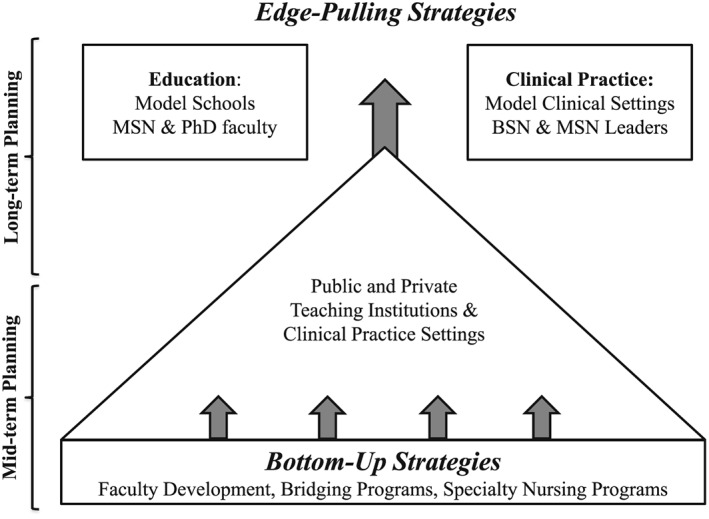

An unanticipated outcome of conducting this study is the emergence of a conceptual model that describes the agents and actions needed to expand the capacity of a nursing workforce in a developing country (Fig. 1). Improving the quality and quantity of nurses/midwives and nursing care requires both capacity building of individual faculty members and at both schools of nursing and health‐care agencies where clinical teaching occurs.12 Meeting these two objectives requires the application of both Edge‐Pulling (leader development) and Bottom‐Up Strategies (quality improvement for teaching staff and nursing professionals). It also requires mid‐term and long‐term strategic planning to generate and maintain momentum in the workforce and in institutions. At the institutional level, the model assumes three aims: (i) creating and developing nursing faculties; (ii) preparing model teaching hospitals/clinical agencies and (iii) providing adequate teaching–learning infrastructures for faculty development. Nursing faculty also requires on‐going professional development and support to keep up with medical and instructional advances. Human resource development does not succeed without parallel improvements in teaching–learning content and teaching environments, which is part of institution‐level capacity building.7 Likewise, there must be a national commitment to build, maintain and furnish schools of nursing with other essential resources like medical libraries, textbook reserves and computer laboratories.

Figure 1.

Model ‐ Nursing Capacity Building in Developing Countries.

At a faculty workforce level, this programme evaluation also uncovered future needs that include developing specialty clinical nursing programmes for faculty and clinical preceptors (mid‐term planning) and ensuring that faculty and clinical preceptors have equivalent degrees plus specialty credentials (long term planning) to ensure collaborative advances in nursing education and clinical practice.7, 11 The elements of this model will exert an optimal impact if aligned with a national strategic plan for health‐care improvement developed in collaboration with key stakeholders at national and regional levels20.

Limitations

This programme evaluation study involved a small number of nursing instructors, clinical preceptors and managers who were employed in the public sector in Cambodia. These subjects were not randomly selected; they were recommended by their collaborating agencies. In addition, data were often collected in group settings. Thus, subjects might have given limited responses. Therefore, the results might not be generalizable to similar programmes originating in the private sector. However, these findings enhance our current understanding of the dynamics and limitations facing nursing education in Cambodia. Future studies should include a larger sample and individuals working in the private sector.

Conclusion

The collaborative BSN programmes offered for Cambodian nurses were effective in improving capacity building in nursing education in both quantitative and qualitative respects. That is, new skills, competencies and abilities were clearly imparted but subjects also reported that they were personally changed by the educational experienced. Careful institution‐level financial support, planning and follow‐up are required to continue, extend and maintain these initial outcomes in Cambodian nursing education. Supports for nursing education also include the need for updating teaching and learning content and strategies, library resources, informatics and investment in educational infrastructures to ensure that faculty capacity development continues to have an impact on nursing school graduates. The model, Nursing Capacity Building in Developing Countries, illustrates the dual nature of capacity building for nursing education by illustrating the aspects of Bottom‐Up Strategies and the Edge‐Pulling Strategies that require strategic planning to bring Cambodian nursing into the 21st century.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the great cooperation of the Human Resource Development Department, MoH, Cambodia for their administrative and technical support. The project described in this report, Strengthening Human Resources Development System of Co‐medicals in Cambodia, was co‐jointly funded by a Japan–Cambodia bilateral cooperation by the Japan International Cooperation Agency and by a Research Grant for International Health, H27‐2, by the MoH, Welfare and Labor, Japan (http://www.ncgm.go.jp/kaihatsu/).

Koto‐Shimada, K. , Yanagisawa,, S. , Boonyanurak, P. , and Fujita, N. (2016) Building the capacity of nursing professionals in Cambodia: Insights from a bridging programme for faculty development. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 22: 22–30. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12436.

References

- 1. Fujita N, Zwi A, Nagai M, Akashi H. A comprehensive framework for human resources for health system development in fragile and post‐conflict states. PLoS Medicine 2011; 8 e1001146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fujita N, Abe K, Rotem A et al. Addressing the human resources crisis: A case study of Cambodia's efforts to reduce maternal mortality (1980–2012). BMJ Open 2013; 3 e002685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kanchanachitra C, Lindelow M, Johnston T et al. Human resources for health in southeast Asia: Shortages, distributional challenges, and international trade in health services. Lancet 2011; 377: 769–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministry of Health (MOH) . Annual Health Workforce Report 2013. Human Resource Department, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2014.

- 5. Sakurai‐Doi Y, Mochizuki N, Phuong K et al. Who provides nursing services in Cambodian hospitals? International Journal of Nursing Practice 2014; 20 (Suppl 1): 39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization . 64th World Health Assembly: Strengthening nursing and midwifery . 2011. Available from URL: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA64/A64_R7‐en.pdf?ua=1. Accessed date: 31 August 2015.

- 7. Evans C, Razia R, Cook E. Building nurse education capacity in India: Insights from a faculty development programme in Andhra Pradesh. BMC Nursing 2013; 12: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ministry of Health (MOH) . Survey on nursing education in the public sector and nursing services at sites for clinical practice in Cambodia. Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2012.

- 9. Ministry of Health (MOH) . Health Sector Progress Report 2014. Phnom Penh, Cambodia, MOH, 2015.

- 10. Fernando J. Collaboration between open universities in the commonwealth: Successful production of the first ever Srilankan nursing graduates at the Open University of Sri Lanka by distance education. 2005. Available from URL: http://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/node/1683. Accessed date:5 September 2015.

- 11. Middleton L, Howard A, Dohrn J et al. The nursing education partnership initiative (NEPI): Innovations in nursing and midwifery education. Academic Medicine 2014; 89: S24–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cancedda C, Farmer P, Kerry V et al. Maximizing the impact of training initiatives for health professionals in low‐income countries: Framewoks, challenges and best practices. PLoS Medicine 2015; 12 (6e1001840). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ministry of Health (MOH) . Assessment of future needs for teachers' capacity building and producing leadership in Nursing and Midwifery (Project: Strengthening human resources development system of co‐medicals.). Funded by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) & Human Resource Department, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, MOH, 2015.

- 14. Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) . Mutual recognition arrangement on nursing services . 2006. Available from URL: http://www.asean.org/communities/asean‐economic‐community/item/asean‐mutual‐recognition‐arrangement‐on‐nursing‐services. Accessed date: 31 August 2015.

- 15. Rotem A, Dewdney J. Mid‐term Review of Health Workforce Development Plan 2006–2015. Ministry of Health, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Knowles M, Holton E, Swanson R. The Adult Learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development, 6th edn. San Diego, California, USA: Elsevier, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Terry L, Carr G, Williams L. The effect of fluency in English on the continuing professional development of nurses educated overseas. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing 2013; 44: 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rotem A, Zinovieff M, Goubarev A. A framework for evaluating the impact of the United Nations fellowship programmes. Human Resources for Health 2010; 8: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rotem A. Draft: Assessment of the WHO/Tonga Fellowship Program, 2013. (personal communication).

- 20. Chen L, Evans T, Anand S et al. Human resources for health: Overcoming the crisis. Lancet 2004; 364: 1984–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]