ABSTRACT

N‐terminal acetylation is a common protein modification in eukaryotes associated with numerous cellular processes. Inherited mutations in NAA10, encoding the catalytic subunit of the major N‐terminal acetylation complex NatA have been associated with diverse, syndromic X‐linked recessive disorders, whereas de novo missense mutations have been reported in one male and one female individual with severe intellectual disability but otherwise unspecific phenotypes. Thus, the full genetic and clinical spectrum of NAA10 deficiency is yet to be delineated. We identified three different novel and one known missense mutation in NAA10, de novo in 11 females, and due to maternal germ line mosaicism in another girl and her more severely affected and deceased brother. In vitro enzymatic assays for the novel, recurrent mutations p.(Arg83Cys) and p.(Phe128Leu) revealed reduced catalytic activity. X‐inactivation was random in five females. The core phenotype of X‐linked NAA10‐related N‐terminal‐acetyltransferase deficiency in both males and females includes developmental delay, severe intellectual disability, postnatal growth failure with severe microcephaly, and skeletal or cardiac anomalies. Genotype–phenotype correlations within and between both genders are complex and may include various factors such as location and nature of mutations, enzymatic stability and activity, and X‐inactivation in females.

Keywords: NAA10, X‐linked, intellectual disability, N‐terminal acetylation

Introduction

N‐terminal acetylation is a common protein modification in eukaryotes [Arnesen et al., 2009]. Recently, N‐terminal acetylation was shown to act as a degradation signal to regulate protein complex stoichiometry, protein complex formation, subcellular targeting, and protein folding [Behnia et al., 2004; Setty et al., 2004; Forte et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2011; Shemorry et al., 2013; Holmes et al., 2014]. It is likely that the physiological role of N‐terminal acetylation may vary, depending on the protein substrate. Six human N‐acetyltransferase enzymes (NATs) have been identified and designated NatA‐NatF [Aksnes et al., 2015]. NatA has a major role and modifies approximately 40% of all human proteins [Arnesen et al., 2009]. It is composed of a catalytic subunit encoded by NAA10 (ARD1; MIM #300013) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim) and an auxiliary subunit encoded by NAA15 (NAT1/NATH; MIM #608000) [Mullen et al., 1989; Arnesen et al., 2005].

In recent years, mutations in the X‐chromosomal NAA10 gene have been implicated in various disease phenotypes. In 2011, Rope et al. identified the same missense mutation, p.(Ser37Pro) in two independent families with Ogden syndrome (MIM #300855), an X‐linked recessive lethal disorder. Five affected males from one family and three affected males from the other family presented with a distinctive phenotype including postnatal growth failure, global severe developmental delay, an aged appearance with reduced subcutaneous fat, skin laxity, wrinkled foreheads, and facial dysmorphism such as prominent eyes, down‐slanting palpebral fissures, thickened lids, large ears, flared nares with hypoplastic alae, short columella, protruding upper lip and microretrognathia. Furthermore, hypotonia progressing to hypertonia, cryptorchidism, hernias, large fontanels, and structural cardiac anomalies and/or arrhythmias were commonly noted. These individuals died between the ages of 5 and 16 months, mainly due to cardiac arrhythmias [Rope et al., 2011].

In 2014, NAA10 was implicated in a second, distinct X‐linked recessive disorder with syndromic microphthalmia (MCOPS1; MIM #309800). Esmailpour et al. identified the splice‐site mutation c.471+2T>A in a family with Lenz microphthalmia syndrome. Several affected males presented with congenital bilateral anophthalmia, postnatal growth failure, hypotonia, skeletal anomalies such as scoliosis, pectus excavatum, finger, and toe syndactyly or clinodactyly, and with abnormal ears, fetal pads, and cardiac and renal anomalies. They had delayed motor development and mild to severe intellectual disability (ID) with remarkable intrafamilial variability. Furthermore, behavioral anomalies and seizures were reported. Three female carriers showed mild symptoms such as abnormally shaped ears and syndactyly of toes [Esmailpour et al., 2014].

Trio whole‐exome sequencing within a larger study revealed the de novo missense mutation p.(Arg116Trp) in a boy with severe intellectual disability [Rauch et al., 2012]. Interestingly, shortly after another de novo missense mutation p.(Val107Phe) was identified in a female [Popp et al., 2015]. Both individuals with de novo mutations had severe cognitive impairment and showed variable other anomalies such as postnatal growth retardation, muscular hypotonia and skeletal, cardiac, and behavioral anomalies [Popp et al., 2015]. However, their phenotype was milder and less recognizable due to fewer malformations compared with the distinct syndromic entities of Ogden and syndromic microphthalmia syndromes [Popp et al., 2015]. Only very recently, another mutation in NAA10, p.(Tyr43Ser), was reported in two brothers with mild to moderate intellectual disability, scoliosis, and long QT and in their mildly affected mother [Casey et al., 2015].

Different levels of remaining enzymatic activity, but also the diversity of NAA10 function, of which various aspects are potentially specifically targeted by different mutations, were discussed as underlying the various NAA10 associated phenotypes [Esmailpour et al., 2014; Aksnes et al., 2015; Casey et al., 2015; Dorfel and Lyon, 2015; Popp et al., 2015]. However, given the small number of affected individuals and genetic variants identified as well as the lack of complete and comparative mechanistic investigations, no solid conclusion could yet be drawn.

We now report on a total of 12 affected females with four different de novo missense mutations in NAA10 and one inherited mutation in a familial case due to germline mosaicism, thus further expanding the mutational and clinical spectrum associated with NAA10 related N‐terminal‐acetyltransferase deficiency.

Material and Methods

Individuals and Mutation Detection

All novel 11 affected females were seen and diagnosed in different centers worldwide. In all but individuals 4, 6, and 7, the mutation was detected by (trio) exome sequencing. Testing strategy in individual 5 has been recently published elsewhere [Thevenon et al., 2016]. In individuals 4, 6, and 7, the mutations were identified by targeted high‐throughput sequencing of 275 genes implicated in intellectual disability (individual 6 and 7) as described elsewhere for a previous version of the sequencing approach [Redin et al., 2014] or by using the TruSight One sequencing panel by Illumina, containing approximately 4,800 disease associated genes (individual 4). In addition, we re‐evaluated in detail a female with de novo mutation in NAA10 who we recently reported (individual 1) [Popp et al., 2015]. Targeted mutation testing in the affected brother of individual 12 was done by Sanger sequencing. Analyses were performed either in a diagnostic or research setting, and informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians of all affected. If done in a research setting, the studies were approved by the ethic committees of the respective universities or centers.

Mutations and their de novo occurrence were confirmed by Sanger sequencing in the respective center. Gene version NM_003491.3 was used as reference. Nucleotide numbering uses +1 as the A of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence, with the initiation codon as codon 1. The identified variants in NAA10 were submitted to the LOVD gene variant database at http://www.lovd.nl/NAA10 (individual IDs 60301—60312).

In silico prediction was performed with online programs SIFT [Kumar et al., 2009] (http://sift.jcvi.org/), PolyPhen‐2 [Adzhubei et al., 2010] (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), and Mutation Taster [Schwarz et al., 2014] (http://www.mutationtaster.org/).

X‐inactivation

X‐Inactivation testing at the androgen receptor locus was performed on lymphocytes of seven individuals according to standard procedures [Allen et al., 1992; Lau et al., 1997].

Homology modelling

Structural consequences of the p.(Arg83Cys), the p.(Phe128Leu), and the p.(Phe128Ile) mutations were studied using a previously established homology model of the human NAA10 enzyme based on the structural coordinates of S. pombe Naa10 [Myklebust et al., 2015] and visualized using MODELLER [Eswar et al., 2007].

Plasmid construction and protein purification

Mutant His/MPB‐NAA10 and NAA10‐V5 plasmids containing the p.(Arg83Cys), the p.(Phe128Leu), or p.(Phe128Ile) mutation were created by site‐directed mutagenesis (QuikChange® Multi Site‐Directed Mutagenesis Kit, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol and as described previously [Popp et al., 2015] with the primers NAA10_R83C_Fwd: 5′ GCGTTCCCACCGGCGCCTCGGTCTGGCTCAGAAACTGATGG and NAA10_R83C_Rev: 5′ CCATCAGTTTCTGAGCCAGACCGAGGCGCCGGTGGGAACGC. Protein purification was performed as described previously [Popp et al., 2015]. Buffers used for protein purification were: IMAC wash buffer (50 mM Tris‐HCl [pH 7.4], 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 25 mM Imidazole), IMAC elution buffer (50 mM Tris‐HCl [pH 7.4], 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 300 mM Imidazole), and size‐exclusion chromatography buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT. All enzymes that were purified and used for enzymatic acetylation assays were more than 95% pure.

In vitro acetylation assays

A colorimetric acetylation assay [Thompson et al., 2004] and a quantitative HPLC assay [Evjenth et al., 2009] were used to measure the catalytic activity of the NAA10 variants as described previously [Popp et al., 2015]. Purified enzyme was mixed with Acetyl‐CoA (Ac‐CoA), substrate peptides, and acetylation buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, and 2 mM EDTA), and reactions were carried out at 37˚C. NAT activity was measured in the linear phase of the reaction. For Km and kcat determination, enzymes were mixed with 500 μM oligopeptide and Ac‐CoA ranging from 10 μM to 1 mM. Due to the low catalytic activity of p.(Phe128Leu), kinetic constants were determined only for NAA10 WT and NAA10 p.(Arg83Cys).

Protein stability analysis for the p.(Arg83Cys) and the p.(Phe128Leu) mutations by cycloheximide chase assay

Cycloheximide chase experiments were performed as described previously [Casey et al., 2015]. Briefly, HeLa cells were plated on six‐well plates and transfected with 2.6 μg plasmid using X‐tremeGENE nine DNA transfection reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Forty eight hours after transfection, 50 μg/ml cycloheximide was added to the cells that subsequently were harvested at 0, 2, 4, and 6 hr post‐treatment. V5‐tagged NAA10 variants were detected using a standard Western blotting procedure with anti‐V5‐tag antibody (R960‐25; Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), anti‐β‐Tubulin antibody (T5293; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and anti‐NAA15 antibody (anti‐NATH). Signals were detected by using ChemiDocTM XRS+ system of Bio‐RAD (Hercules, CA), and normalization and quantification of the signals was done with ImageLabTM system 5 of Bio‐RAD. Each mutant was analyzed at least three times in independent experiments.

Results

Mutational Spectrum

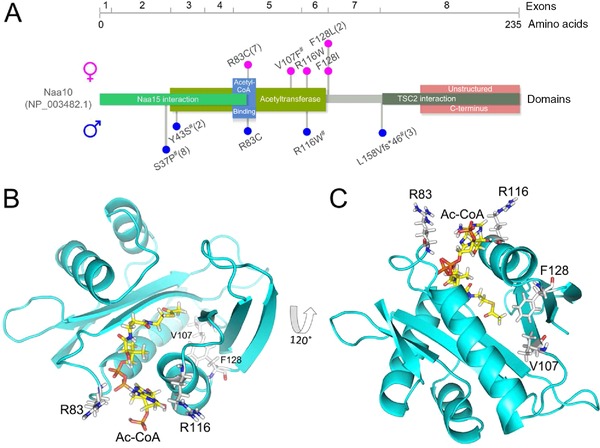

Five different missense mutations in NAA10 were identified in 12 female patients and one affected male (Fig. 1A; Supp. Table S1). The p.(Val107Phe) mutation has been reported previously [Popp et al., 2015] and is so far unique. Also, the p.(Arg116Trp) mutation has been reported previously, but in an affected boy [Popp et al., 2015]. Two mutations, p.(Phe128Ile) and p.(Phe128Leu), affect the same, highly conserved amino acid. The mutation p.(Phe128Ile) was identified in one female as recently reported [Thevenon et al., 2016], whereas p.(Phe128Leu) was identified in two unrelated female individuals. The recurrent mutation p.(Arg83Cys) was detected in seven females, one of them having an affected brother who deceased at the age of 1 week. In this family, maternal germ line mosaicism was assumed because exome data did not reveal the mutation in the mother's blood sample and because of recurrence in a third pregnancy terminated after prenatal diagnosis. In all other 11 individuals, the mutation was shown to have occurred de novo.

Figure 1.

Mutations identified in NAA10. A: Schematic representation of the NAA10 protein, encoding exons (numbered after NM_003491.3), domains (based on NCBI reference NP_003482.1, UniProt P41227 and the crystal structure of the NatA complex [Liszczak et al., 2013]), and localization of mutations in affected males (blue circles) and females (red circles). #, previously published mutations [Rauch et al., 2012; Rope et al., 2011; Esmailpour et al., 2014; Popp et al., 2015]. One letter codes were used due to space constraint. For the mutation c.471+2T>A described by Esmailpour et al. (2014) and the deduced protein level changes (p.(Leu158Valfs*46), p.(Glu157_Leu158ins9)), the presumably expressed truncated transcript 1 was used for labelling. B: NAA10 homology model highlighting Arginine 83 and 116. These are localized in the Ac‐CoA binding pocket. C: NAA10 homology model showing the localization of Phe128, with its side chain pointing toward the hydrophobic core, similar to Val107. This amino acid was mutated in a previously published patient [Popp et al., 2015].

None of the five missense mutations was found in the ExAC browser [Lek et al., 2015] (status November 2015) (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/). All affect highly conserved amino acids (Supp. Fig. S1 and [Popp et al., 2015]) and were classified as damaging or disease causing by Mutation Taster and SIFT and four of them as possibly or probably damaging by PolyPhen‐2 (Supp. Table S2). X‐inactivation was random in four tested individuals, mildly skewed (92%) in one and completely skewed (100%) in another.

Clinical Phenotype

Clinical details of the affected individuals are displayed in Table 1. All 12 females are moderately to severely intellectually disabled. Age of walking ranges from 18 months to not being able to walk unassisted at age 8 years 6 months. Age of first words ranges from 15 months to no speech at age 8 years 6 months. Most of the individuals, though many still young, are nonverbal; one is reported to have a good vocabulary but not regularly using full sentences. Behavioral anomalies are described in seven girls and include stereotypic movements, self‐hugging, attention deficit, aggressivity, and unmotivated laughter. Possible seizures or EEG anomalies were reported in only two of the individuals.

Table 1.

Clinical Details of Patients with De Novo Mutations in NAA10

| Individual | 1 [Popp et al., 2015] | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 [Thevenon et al., 2016] | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12* | 13* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA10 mutation | c.319G>T, p.(Val107Phe) | c.346C>T, p.(Arg116Trp) | c.384T>A, p.(Phe128Leu) | c.384T>A, p.(Phe128Leu) | c.382T>A , p.(Phe128Ile) | c.247C>T, p.(Arg83Cys) | c.247C>T, p.(Arg83Cys) | c.247C>T, p.(Arg83Cys) | c.247C>T, p.(Arg83Cys) | c.247C>T, p.(Arg83Cys) | c.247C>T, p.(Arg83Cys) | c.247C>T, p.(Arg83Cys) | c.247C>T, p.(Arg83Cys) |

| X‐inact. | Random | Random | Random | NA | Random | Random | 92% | NA | NA | NA | 100% | NA | NA |

| Inheritance | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | MGM | MGM |

| Mutation detected by | Trio exome | Trio exome | Exome | Trio panel (TS1) | Trio exome | Panel | Panel | Trio exome | Exome | Exome | Trio exome | Trio exome | Targeted |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Male |

| Age last investigat. | 8y 2mo | 8y 1mo | 17mo | 8y 6mo | 6y 5mo | 4y 2mo | 4y 3mo | 2y 2mo | 3y 10mo | 10y 6mo | 4y | 6y 6mo | 1wk/†1wk |

| Birth | |||||||||||||

| Gestational week | Term | 39+2 | 41 | 34 | Term | Term | Term | 34 (twins) | 38+1 | 37+1 | 40 | 41 | 36 |

| Weight (g/SD) | Normal | 3,350/0 | 3,020/−1.2 | 1,700/−1.3 | 2,670/−1.65 | 3,290/−0.25 | 3,095/−0.67 | 2,210/0.2 | 2,540/−1.21 | 3,175/0.65 | 2,500/−2.31 | 3,470/−0.25 | 3,210/1.1 |

| Length (cm/SD) | Normal | 49/−1 | 51/−0.13 | NA | 47/−1.51 | 51/−0.25 | 47/−1.51 | 44/0 | 48/−0.3 | 52/1.72 | 49/−1.23 | NA | NA |

| OFC (cm/SD) | NA | NA | 32/−2.07 | NA | 32/−1.96 | NA | 34/−0.51 | 30.5/0.1 | 32.4/−0.89 | NA | NA | NA | 35.5/1.9 |

| Growth | |||||||||||||

| Growth failure | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NA |

| Height (cm/SD) | 108/−3.79 | 140/1.4 | 83.1/−0.92 | 115/−2.5 | 105/−2.65 | 97/−1.44 | 97/−1.6 | 79.5/−2.56 | 88.3/−3.15 | 144/0.06 | Normal | 90/−1.62 (3y 2mo) | NA |

| Weight (kg/SD) | 17.5/−2.9 | 33.7/0.5 | ?/−0.39 | 17.2/−2.5 | 13.1/−4.12 | 15/−0.8 | 12.6/−2.46 | 9.76/−2.26 | 11.2/−3.16 | 35/0.54 | Normal | 14/−0.35 (3y 2mo) | NA |

| OFC (cm/SD) | 48.5/−3.01 | 51/−0.3 | 41.7/−5.3 | 46/−4 | 46.2/−5.15 | 47/−3.5 | 47/−3.59 | 44.7/−3.86 | 44.5/−4.85 (3y 5mo) | 48 cm/−2.8 (6y) | 48.5/−1.27 | 45/−4.58 (3y 2mo) | NA |

| CNS | |||||||||||||

| Developm. delay/ID | Severe | Moderate (IQ ∼ 50) | Severe | Profound | Yes | Severe | Yes | Severe | Severe | Moderate | Severe | Severe | NA |

| Age of walking | 5y | 18mo | Not yet | Not yet | 18mo | Not yet (3y 6mo) | Not yet | Not yet | 3y | 24mo | Not yet | NA | |

| First words/current speech | Not yet/signs and sounds | 15mo | Not yet/consonant babbles | Not yet | Not yet | 2y (2 words) | Not yet | Not yet | 3y / good, but not always full sentences | Not yet | Not yet, sounds | NA | |

| Seizures (age) | No | No | Infantile spasms (4mo) | 5y | No | No | No | No | "Spells" vs. seizures | No | No | No | NA |

| EEG anomalies | NA | Myoclonic, generalized | Bifrontal slow‐waves, spike‐waves | NA | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | |||

| Hypotonia/hypertonia | Axial hypo/periph hyper | Hypo | Severe hypo | Axial hypo/periph hyper | Axial hypo/periph hyper | Hypo | Hypo | Hypo (axial > periph) | Hypo/hyper | Hypo | No | Periph hyper | Hypo |

| Brain imaging anomalies | US normal | MRI normal (6y) | MRI (9mo): parenchymal atrophy, thin CC | Normal (1y) | Supraventricular cyst without hydrocephaly | No | Hippocampic dysgenesis | MRI (20mo): periventr. white matter loss | IVH occipital horn, PVL, HIE | MRI normal (12mo, 3y) | |||

| Borderline ventriculomegaly | MRI: thin CC | Dilated lat. ventricles, thin CC | US (pre‐ and perinatal): ventriculomegaly | ||||||||||

| Behavioral anomalies | Active, short attention span, friendly | ADHD | No | Stereotypies, hand washing, uncertain eye contact | Unmotivated laughter | Aggressivity | No | Happy disposition | Very active, happy, problems in new settings | Hyperactivity, little eye contact, aggressivity | Restlessness, attention deficit, happy disposition | NA | |

| Visceral | |||||||||||||

| Cardiac anomalies | PAS, ASD, long QT (max QT time 484 ms) | Incomplete richt bundle branch block | Mild left ventr. diastolic dysfunction, ECG normal | No | Incomplete right bundle branch block | No | No | Mild PAS, PFO vs. ASD | No | Long QT | Incomplete right bundle branch block | No | SVT, pulm. hypert., mild ventric. hypertrophy |

| Eye anomalies | Astigmatism, strabism, mild opticus atrophy | No | Cortical vision impairment | Cortical visual impairment, amblyopia | Hyperopia, astigmatism, exotropia | No | No | Myopia, astigmatism | Alternating esotropia, cortical vision impairment | Astigmatism, hyperopia | Hyperopia | Megalopapillae, myopia | NA |

| Urogenital/kidney anomalies | No | NA | NA | NA | No | NA | No | NA | No | Prenatal renal fluid | No | Small cysts unilateral | Diffuse small cortical kidney cysts |

| Skeletal | |||||||||||||

| Large fontanels | Yes | No | No | NA | NA | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Delayed bone age | Yes | NA | NA | No | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hand anomalies | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Small hands | No | Clinodactyly V | Small hands, tapering fingers | NA |

| Feet anomalies | Broad great toes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Small | No | No | Small feet and toes | Hallux varus, sandal gap |

| Thoracic anomalies | Mild pectus carinatum | No | No | No | No | No | No | Supernumerary vertebra, dysmorphic L1 vertebra | Yes | Mild pectus excavatum | Pectus excavatum | Pectus excavatum | NA |

| Other | |||||||||||||

| Feeding difficulties | Yes, infancy | No | Yes, g‐tube | Yes, tube in infancy, choking | Yes | Yes | No | Yes, infancy | Yes | Mild, in infancy | Yes, infancy | NA | NA |

| Other anomalies or difficulties | Recurrent infections, high pain threshold | DCD | Pyramidal signs, dystonic postures | Narrow palate | VP shunt, high palate | Resolved cutis marmorata | Sleeping problems | Cutis marmorata | |||||

*siblings.

MGM, maternal germline mosaicism; anom., anomalies; TS1, Trusight One sequencing panel (Illumina); †, deceased; mut., mutation; mo, months; y, years; wk(s), week(s); NA, not available/applicable; OFC, occipitofrontal head circumference; CNS, central nervous system; ID, intellectual disability; US, ultrasound; CC, corpus callosum; US, ultrasound; hyop, hypotonia; hyper, hypertonia; periph, peripheral; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; PAS, pulmonary artery stenosis; ASD, atrial septum defect; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; US, ultrasound; DCD, (developmental coordination disorder); HIE, hypoxic‐ischemic encephalopathy; PVL, periventricular leukomalacia; VP, ventriculo‐peritoneal.

Birth measurements were in the normal or low normal range for most of the individuals. However, postnatal growth failure of length and/or head circumference occurred in most of the girls for whom this data were available. At age of last investigation (17 months–9 years), all but individuals 2 and 11 had head circumferences between −2.8 to −5.3 standard deviations (SD) below the mean. In relation, growth retardation regarding height was milder, and at age of last investigation length/height was in the normal or low normal range in seven individuals and between −2.5 and −3.75 SD in five. Feeding difficulties, either temporarily in infancy or continuously with the need of tube feeding, were reported in nine girls.

Muscular hypotonia was noted in almost all individuals, often more pronounced axially and with hypertonia of the extremities. Brain imaging, either by MRI or CNS ultrasound revealed frequent but rather unspecific anomalies. Structural cardiac anomalies such as pulmonary stenosis and atrium septum defects were observed in two females, cardiac conduction anomalies in five (twice long QT and three times incomplete right bundle branch block). Large fontanels were reported in four girls, and delayed bone age in one, but not tested in the others. Skeletal anomalies such as pectus excavatum or carinatum or vertebral anomalies were reported in five girls.

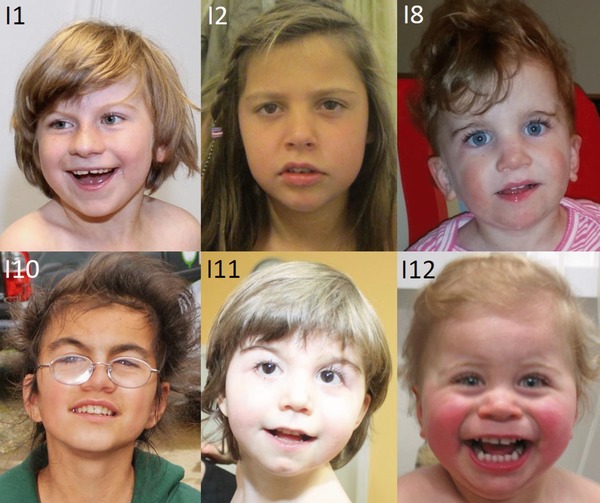

Various, but rather unspecific facial dysmorphism such as bitemporal narrowing, mildly up‐slanting palpebral fissures, a prominent forehead, uplifted earlobes, hirsutism, or an up‐turned nose were common. In several individuals, long eyelashes and arched, prominent eyebrows, or synophrys were noted (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Facial phenotypes of females with NAA10‐related N‐terminal‐acetyltransferase deficiency. Note only minor dysmorphic aspects and a rather unspecific facial gestalt in most of the girls. Some have prominent or arched eyebrows.

In one of the families, the p.(Arg83Cys) mutation also occurred in an affected brother due to maternal germ line mosaicism. This boy was born at gestational week 36 with normal birth length and weight. He had generalized hypotonia, lack of spontaneous respiration, and died at age 1 week. He had persistent pulmonary hypertension, supraventricular tachycardia, and mild ventricular hypertrophy. Ultrasound examination of the CNS showed ventriculomegaly, and small cortical kidney cysts were noted. Furthermore, he was reported to have had large fontanels, bilateral hallux valgi, sandal gaps, a broad forehead, and micrognathia. A third, male pregnancy in this family was terminated after identifying the NAA10 mutation prenatally.

Homology Modelling

The missense mutation p.(Arg83Cys) is located in the Ac‐CoA binding site of NAA10, and the amino acid Arg83 might thus play an important role in the recruitment of Ac‐CoA to the enzyme (Fig. 1B). The amino acids Arg83 and Arg116, the latter also mutated in a male individual (p.Arg116Trp) in an earlier study [Popp et al., 2015], are both positively charged and positioned on the rim of the Ac‐CoA binding site. We thus suspect that the p.(Arg83Cys) mutation will have similar (or more adverse) effects as the p.(Arg116Trp) mutation previously identified. Phe128 on the other hand is not located in the active site of the enzyme (Fig. 1C). This residue is located in the loop region between α4 and β6 of NAA10. The sidechain of Phe128 is pointing in toward a hydrophobic pocket between β4, α3, β5, α4, and β7. Previously, we described the p.(Val107Phe) variant whose sidechain is pointing toward the very same hydrophobic pocket and which resulted in more than 90% reduction of catalytic activity, most likely due to structural alterations or a reduced stability [Popp et al., 2015]. This indicates that the large bulky sidechain of Phe128 is necessary for this hydrophobic pocket and that the introduction of the much smaller Leucine or Isoleucine is causing a destabilization of the enzyme.

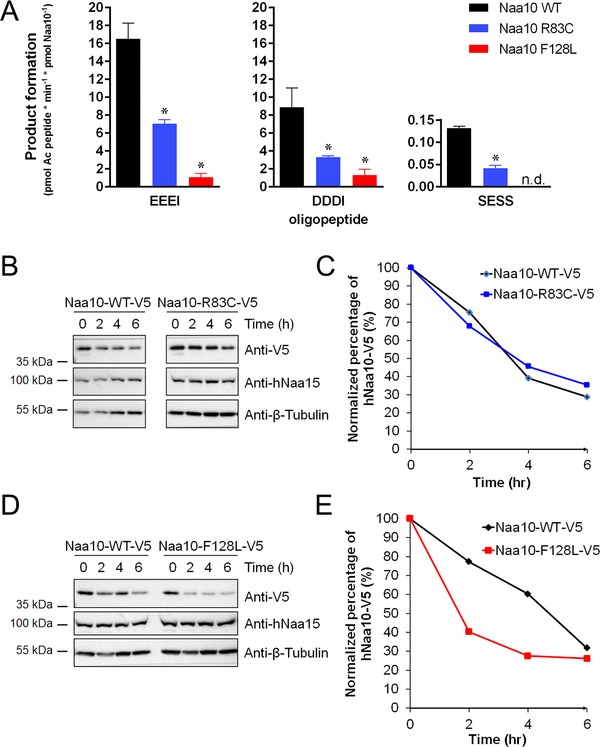

In vitro enzymatic assays and in cellula stability measurements

In order to study the catalytic activity of NAA10 variants, plasmids coding for a His/MBP‐NAA10 WT fusion protein, a His/MBP‐NAA10 p.(Arg83Cys) fusion protein and a His/MBP‐NAA10 p.(Phe128Leu) fusion protein were expressed in E. coli BL21 cells and purified. Interestingly, while NAA10 WT and NAA10 p.(Arg83Cys) eluted as monomers from the size‐exclusion chromatography column, the NAA10 p.(Phe128Leu) eluted mainly in the void volume of the column (Supp. Fig. S2). This was also seen for another previously described NAA10 variant (p.(Tyr43Ser)) [Casey et al., 2015], and suggests that the protein has an altered protein structure or a reduced protein stability, causing it to aggregate in units larger than 200 kDa. For further enzymatic testing, only fractions of monomeric enzymes were used.

In vitro enzymatic assays revealed a drastic reduction of catalytic activity for NAA10 p.(Phe128Leu) (similarly to previously published NAA10 p.(Val107Phe) [Popp et al., 2015] and p.(Tyr43Ser) [Casey et al., 2015]), whereas the p.(Arg83Cys) mutation resulted in an approximately 60% reduction of catalytic activity (Fig. 3A). Together, these data support our findings from the homology model, suggesting that the p.(Phe128Leu) and p.(Phe128Ile) mutations interfere with the overall structure of NAA10 and possibly also destabilize the protein, whereas the p.(Arg83Cys) mutation interferes with Ac‐CoA binding.

Figure 3.

Functional consequences of NAA10 mutations. A: Purified wild‐type (WT) or mutant NAA10 were each mixed with acetylation buffer, 500 μM peptide and 500 μM Ac‐CoA, and incubated at 37°C. Reactions were stopped in the linear phase of the reaction. The p.(Arg83Cys) mutation resulted in an approximately 60% reduction in catalytic activity of NAA10 for all tested oligopeptides, whereas the p.(Phe128Leu) mutation lead to a very low catalytic activity (more than 90% reduction). B–E: NAA10 stability in vivo, tested pairwise (mutant and control) by cyclohexamide chase experiments and monitored at different time points (between 0 and 6 hr post‐treatment) and by Western blotting. Figures show representative results from at least three independent experiments. B: Western blot for NAA10‐V5 WT or NAA10‐V5 carrying the mutation p.(Arg83C). Bands were quantified, and the relative amount of NAA10 present at each time point is showed in (C). D: Western blot for NAA10‐V5 WT or NAA10‐V5 carrying the mutation p.(Phe128Leu). Bands were quantified, and the relative amount of NAA10 present at each time point is showed in (E).

In order to further study whether the p.(Arg83Cys) mutation affects Ac‐CoA, we determined steady‐state kinetic constants (Supp. Fig. S3). The Km for Ac‐CoA is approximately threefold higher for the p.(Arg83Cys) variant compared with wild‐type (WT) NAA10, indicating that the p.(Arg83Cys) variant has a reduced affinity toward Ac‐CoA, and that this is the main cause of the reduced overall catalytic activity for this variant.

We also assessed the stability of the NAA10 variants by overexpression in HeLa cells followed by cycloheximide‐chase experiments. The NAA10 p.(Phe128Leu) variant was less stable compared with NAA10 WT (Fig. 3B–E). Similar findings were observed for NAA10 Phe128Ile (data not shown). In contrast, protein stability does not seem to be affected by the p.(Arg83Cys) mutation.

Discussion

Delineation of the Phenotype in Females with NAA10‐Related N‐Terminal‐Acetyltransferase Deficiency

We describe 12 female individuals, 11 of whom carry de novo missense mutations in NAA10, a gene previously implicated in different X‐linked recessive disorders. The herewith reported females all have moderate to severe ID and variable other anomalies, partly overlapping with those in the affected males but with a generally milder and less characteristic phenotype.

Several common clinical aspects could be noted among the affected females. All had moderate to severe developmental delay and ID with no or very limited speech and often with limited mobility. While birth measurements were often in the normal or low normal range, postnatal growth failure commonly occurred, also resulting in severe microcephaly. Skeletal, brain, and organ anomalies were frequent, but without any apparent specific pattern. Minor, but often rather unspecific facial dysmorphism were observed in most of the patients. In several individuals, arched eyebrows or synophrys were noted, which, if present, in combination with short stature and intellectual disability might bear some resemblance to Cornelia‐de‐Lange syndrome (CDLS1; MIM #122470, CDLS2; MIM #300590, CDLS3; MIM #610759, CDLS4; MIM #614701, CDLS5; MIM #300882). As the p.(Arg83Cys) mutation was recurrently identified in seven girls, we wondered whether it might be accompanied by specific phenotypic aspects. However, we could not deduce any obvious differences in clinical appearance between individuals with this mutation or one of the other missense mutations.

Importantly, cardiac conduction anomalies were observed in five of the females. This might be a milder manifestation of the cardiac arrhythmias that were frequent and often lethal in many of the boys with Ogden syndrome [Rope et al., 2011]. Also, very recently, long‐QT was observed in two male individuals and their mother with NAA10‐related N‐terminal acetylation deficiency [Casey et al., 2015]. As the observation of conduction defects has important consequences, such anomalies should be specifically tested in newly identified individuals. Furthermore, specific recommendations for surveillance, medication, or avoidance of risk factors should be given to families with affected children. As long as little information on the course of NAA10‐related N‐terminal‐acetyltransferase deficiency in females is available, general recommendations for cardiac conduction anomalies such as long‐QT syndrome might be applied. One should also consider electrocardiographic examination in otherwise asymptomatic female carriers in families with X‐linked recessive NAA10‐related N‐terminal‐acetyltransferase deficiency, as conduction anomalies might occur as a minimal manifestation of the disease in them, similar to cardiomyopathies in female carriers of Duchenne muscular dystrophy [Hoogerwaard et al., 1999].

Genotype–Phenotype Correlations

Developmental delay and intellectual disability, postnatal growth failure, and cardiac and skeletal anomalies are overlapping clinical aspects between male individuals with X‐linked recessive Ogden syndrome and syndromic microphthalmia and with males or females with severe ID due to de novo mutations in NAA10. These features therefore probably represent general clinical consequences of NAA10‐related N‐terminal acetylation deficiency. We therefore suggest using this or the shorter term “NAA10 deficiency” to describe the associated phenotypes instead of splitting them into different syndromic entities. The more specific aspects such as aged appearance or wrinkled skin in Ogden syndrome [Rope et al., 2011], anophthalmia, seizures, and syndactyly in syndromic microphthalmia [Esmailpour et al., 2014] or a rather mild phenotype in two brothers with mild to moderate ID, scoliosis, and long‐QT [Casey et al., 2015] might be related to specific effects of the respective, causative mutations.

Different levels of remaining enzymatic activity and specifically affected properties of NAA10 function were reported for different NAA10 mutations [Esmailpour et al., 2014; Aksnes et al., 2015; Casey et al., 2015; Dorfel and Lyon, 2015; Popp et al., 2015]. In the family with syndromic microphthalmia due to a splice‐site mutation (c.471+2T>A), absent expression of WT NAA10 in fibroblasts derived from affected individuals and only minimal expression of mutant NAA10 was shown [Esmailpour et al., 2014]. For the p.(Ser37Pro) mutation from the Ogden syndrome families, disruption of the catalytic activity was confirmed [Rope et al., 2011]. Furthermore, the integrity of the NatA complex was disturbed and N‐terminal acetylome analyses of B‐cells, and fibroblasts from affected individuals revealed a reduction of the NatA‐mediated N‐terminal acetylation [Van Damme et al., 2014; Myklebust et al., 2015]. In contrast, the de novo p.(Arg116Trp) mutation resulted in a high remaining catalytic activity, therefore being in accordance with the relatively mild phenotype in the affected boy [Popp et al., 2015], whereas the de novo p.(Val107Phe) mutation, identified in a girl, had a more severe effect with almost abolished catalytic activity, thus explaining the pronounced manifestation of symptoms in a female [Popp et al., 2015].

However, the hypothesis of phenotypic severity correlating with levels of catalytic activity is challenged by a report on two affected brothers with a rather mild phenotype but carrying a mutation with a severe impact on catalytic activity [Casey et al., 2015].

Our functional studies, comparing all de novo missense mutations identified in females, show that the p.(Phe128Leu) and the p.(Phe128Ile) mutations cause a reduced stability of NAA10 and loss of NAA10 NAT‐activity. Based on the close proximity of Phe128 and Val107 in the NAA10 structure, our data suggest that individuals with either mutation might be affected through the same molecular mechanisms. The p.(Arg83Cys) mutation also has a clearly reduced catalytic activity, due to a lower affinity for AC−CoA, but does not seem to affect NAA10 structurally. The homogenous phenotype in all girls with either the p.(Val107Phe), p.(Phe128Leu), p.(Phe128Ile), or p.(Arg83Cys) mutation suggests that rather the loss of the NAT activity, which is shared by all missense mutations, and not the impaired structural stability, found for all but the p.(Arg83Cys) mutation, is underlying their similar phenotype. The milder catalytic impairment by the p.(Arg83Cys) mutation of 60% compared to a >90% abolishment of catalytic activity by p.(Phe128Leu) or the previously published p.(Val107Phe) variant is not reflected in an obviously milder clinical phenotype in the respective individuals, suggesting a critical threshold of enzyme activity necessary for normal function. This critical threshold might, however, be met by individual 2. She showed a milder phenotype with an IQ of 50 and no postnatal growth deficiency. This girl carries the mutation p.(Arg116Trp), that has previously been shown to result in a rather mild reduction of NAA10 catalytic activity [Popp et al., 2015].

According to the observation of the p.(Arg116Trp) mutation causing a more severe phenotype in a male [Popp et al., 2015] compared to the herewith reported female, also the other missense mutations might have a significantly more pronounced effect in males, possibly leading to lethality. This would be in accordance with the observation in family 12, in which the affected boy deceased 1 week after birth. Nevertheless, the contrast between the severe ID and microcephaly phenotypes in the herewith reported females with mainly de novo mutations in NAA10 and the mostly asymptomatic carrier females in families with Ogden and Lenz microphthalmia syndromes is still striking. A possible cause might be the X‐inactivation pattern. Its possible impact on the phenotype is reflected in Individual 11. This girl has an 100% skewed X‐inactivation in lymphocytes and is the only individual carrying the p.(Arg83Cys) mutation but not showing microcephaly or postnatal growth retardation. In contrast, X‐inactivation was random in lymphocytes of four of the other five tested females in our study and only mildly skewed in the fifth. All carrier females in the original Ogden syndrome family were reported to have skewed X‐inactivation, which would be in accordance with them not showing any or only mild symptoms [Myklebust et al., 2015]. However, an explanation why skewing of X‐inactivation occurred in the females with inherited mutations and only twice in the females with de novo mutations and still causing a severe phenotype, is still lacking. As NAA10‐related N‐terminal acetyltransferase deficiency seems to be caused by different mutations and to be accompanied by various phenotypes, there might be tissue specificity or a correlation between specific mutations and skewing or nonskewing of X‐inactivation.

De novo mutations in X‐linked recessive genes in females

The relatively high number of 12 individuals indicates that missense mutations affecting the catalytic activity of X‐chromosomal encoded NAA10 might be a relatively frequent cause of severe ID in females. Similar observations of de novo mutations in X‐linked genes causing severe ID phenotypes in females while female carriers of mutations in families with affected males were normal, were recently made for other genes such as DDX3X (MIM# 300160) [Snijders Blok et al., 2015] or PHF6 (MIM# 300414) [Zweier et al., 2013]. We therefore hypothesize that de novo mutations in supposedly X‐linked recessive genes might be more common than previously expected.

To conclude, our findings show that different missense mutations in NAA10 in females result in severe ID and postnatal growth failure with severe microcephaly and thus expand the clinical and mutational spectrum associated with X‐linked NAA10 related N‐terminal‐acetyltransferase deficiency. Particularly the observation of cardiac conduction anomalies in both males and females has relevant consequences for the clinical management of known and newly identified individuals.

Disclosure statement: The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Supporting information

Disclaimer: Supplementary materials have been peer‐reviewed but not copyedited.

Figure S1. Amino acid sequence of NAA10 orthologues. (A) Arg83 is highly conserved through evolution. In A. thaliana and S. pombe the arginine is substituted with either a lysine or histidine, both of which has a positively charged side chain and encompasses many of the same properties as an arginine. Similarly, Phe128 is highly conserved. In A. thaliana, this phenylalanine is substituted with the highly similar tyrosine residue. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of all the known catalytic NAT‐subunits. Similarly as in (A) both Arg83 and Phe128 are mostly conserved, suggesting that these amino acids have a functional role in the Naa10 enzyme. *, Val107, affected by the previously published p.(Val107Phe) mutation [Popp et al., 2015].

Figure S2. Elution profile from the size‐exclusion step of NAA10 purification. NAA10 p.(Phe128Leu) mostly elutes in the void volume of the superdex 200 column, suggesting that this protein forms aggregates or multimers larger than 200 kDa in size (tetramer or higher). Fractions of monomeric NAA10 were collected and used for in vitro acetylation assays.

Figure S3. (A) Determination of kinetic constants for NAA10 wild type and NAA10 p.(Arg83Cys). Enzymes were mixed with 500 μM oligopeptide and Ac‐CoA ranging from 10 μM to 1mM. Kinetic constants were determined by GraphPad Prism 6 and are summarized in (B).

Table S1. Genomic positions of mutations

Table S2. in silico prediction of mutations

Acknowledgments

We thank the families for their participation. The authors would like to thank the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project and its ongoing studies that produced and provided exome variant calls for comparison: the Lung GO Sequencing Project (HL‐102923), the WHI Sequencing Project (HL‐102924), the Broad GO Sequencing Project (HL‐102925), the Seattle GO Sequencing Project (HL‐102926), and the Heart GO Sequencing Project (HL‐103010).

Contract grant sponsors: Dijon University Hospital; Regional Council of Burgundy; Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF) Erlangen (projects E16 and E26); German Research Foundation DFG (Zw184/1‐2); Norwegian Cancer Society; The Bergen Research Foundation BFS; Research Council of Norway (grant 230865); Western Norway Regional Health Authority.

Communicated by Stephen Robertson

References

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. 2010. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 7:248–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksnes H, Hole K, Arnesen T. 2015. Molecular, cellular, and physiological significance of N‐terminal acetylation. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 316:267–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RC, Zoghbi HY, Moseley AB, Rosenblatt HM, Belmont JW. 1992. Methylation of HpaII and HhaI sites near the polymorphic CAG repeat in the human androgen‐receptor gene correlates with X chromosome inactivation. Am J Hum Genet 51:1229–1239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen T, Anderson D, Baldersheim C, Lanotte M, Varhaug JE, Lillehaug JR. 2005. Identification and characterization of the human ARD1‐NATH protein acetyltransferase complex. Biochem J 386:433–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen T, Van Damme P, Polevoda B, Helsens K, Evjenth R, Colaert N, Varhaug JE, Vandekerckhove J, Lillehaug JR, Sherman F, Gevaert K. 2009. Proteomics analyses reveal the evolutionary conservation and divergence of N‐terminal acetyltransferases from yeast and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:8157–8162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnia R, Panic B, Whyte JR, Munro S. 2004. Targeting of the Arf‐like GTPase Arl3p to the Golgi requires N‐terminal acetylation and the membrane protein Sys1p. Nat Cell Biol 6:405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey JP, Stove SI, McGorrian C, Galvin J, Blenski M, Dunne A, Ennis S, Brett F, King MD, Arnesen T, Lynch SA. 2015. NAA10 mutation causing a novel intellectual disability syndrome with Long QT due to N‐terminal acetyltransferase impairment. Sci Rep 5:16022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfel MJ, Lyon GJ. 2015. The biological functions of Naa10—from amino‐terminal acetylation to human disease. Gene 567:103–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmailpour T, Riazifar H, Liu L, Donkervoort S, Huang VH, Madaan S, Shoucri BM, Busch A, Wu J, Towbin A, Chadwick RB, Sequeira A, et al. 2014. A splice donor mutation in NAA10 results in the dysregulation of the retinoic acid signalling pathway and causes Lenz microphthalmia syndrome. J Med Genet 51:185–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswar N, Webb B, Marti‐Renom MA, Madhusudhan MS, Eramian D, Shen MY, Pieper U, Sali A. 2007. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Protein Sci Chapter 2:Unit 2:9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evjenth R, Hole K, Ziegler M, Lillehaug JR. 2009. Application of reverse‐phase HPLC to quantify oligopeptide acetylation eliminates interference from unspecific acetyl CoA hydrolysis. BMC Proc 3 Suppl 6:S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte GM, Pool MR, Stirling CJ. 2011. N‐terminal acetylation inhibits protein targeting to the endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS Biol 9:e1001073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WM, Mannakee BK, Gutenkunst RN, Serio TR. 2014. Loss of amino‐terminal acetylation suppresses a prion phenotype by modulating global protein folding. Nat Commun 5:4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogerwaard EM, Bakker E, Ippel PF, Oosterwijk JC, Majoor‐Krakauer DF, Leschot NJ, Van Essen AJ, Brunner HG, van der Wouw PA, Wilde AA, de Visser M. 1999. Signs and symptoms of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and Becker muscular dystrophy among carriers in The Netherlands: a cohort study. Lancet 353:2116–2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. 2009. Predicting the effects of coding non‐synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc 4:1073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AW, Brown CJ, Penaherrera M, Langlois S, Kalousek DK, Robinson WP. 1997. Skewed X‐chromosome inactivation is common in fetuses or newborns associated with confined placental mosaicism. Am J Hum Genet 61:1353–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lek M, Karczewski K, Minikel E, Samocha K, Banks E, Fennell T, O'Donnell‐Luria A, Ware J, Hill A, Cummings B, Tukiainen T, Birnbaum D, et al. 2015. Analysis of protein‐coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. bioRxiv. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/030338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liszczak G, Goldberg JM, Foyn H, Petersson EJ, Arnesen T, Marmorstein R. 2013. Molecular basis for N‐terminal acetylation by the heterodimeric NatA complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:1098–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen JR, Kayne PS, Moerschell RP, Tsunasawa S, Gribskov M, Colavito‐Shepanski M, Grunstein M, Sherman F, Sternglanz R. 1989. Identification and characterization of genes and mutants for an N‐terminal acetyltransferase from yeast. EMBO J 8:2067–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myklebust LM, Van Damme P, Stove SI, Dorfel MJ, Abboud A, Kalvik TV, Grauffel C, Jonckheere V, Wu Y, Swensen J, Kaasa H, Liszczak G, et al. 2015. Biochemical and cellular analysis of Ogden syndrome reveals downstream Nt‐acetylation defects. Hum Mol Genet 24:1956–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp B, Stove SI, Endele S, Myklebust LM, Hoyer J, Sticht H, Azzarello‐Burri S, Rauch A, Arnesen T, Reis A. 2015. De novo missense mutations in the NAA10 gene cause severe non‐syndromic developmental delay in males and females. Eur J Hum Genet 23:602–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch A, Wieczorek D, Graf E, Wieland T, Endele S, Schwarzmayr T, Albrecht B, Bartholdi D, Beygo J, Di Donato N, Dufke A, Cremer K, et al. 2012. Range of genetic mutations associated with severe non‐syndromic sporadic intellectual disability: an exome sequencing study. Lancet 380:1674–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redin C, Gerard B, Lauer J, Herenger Y, Muller J, Quartier A, Masurel‐Paulet A, Willems M, Lesca G, El‐Chehadeh S, Le Gras S, Vicaire S, et al. 2014. Efficient strategy for the molecular diagnosis of intellectual disability using targeted high‐throughput sequencing. J Med Genet 51:724–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rope AF, Wang K, Evjenth R, Xing J, Johnston JJ, Swensen JJ, Johnson WE, Moore B, Huff CD, Bird LM, Carey JC, Opitz JM, et al. 2011. Using VAAST to identify an X‐linked disorder resulting in lethality in male infants due to N‐terminal acetyltransferase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet 89:28–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D. 2014. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep‐sequencing age. Nat Methods 11:361–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DC, Monda JK, Bennett EJ, Harper JW, Schulman BA. 2011. N‐terminal acetylation acts as an avidity enhancer within an interconnected multiprotein complex. Science 334:674–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setty SR, Strochlic TI, Tong AH, Boone C, Burd CG. 2004. Golgi targeting of ARF‐like GTPase Arl3p requires its Nalpha‐acetylation and the integral membrane protein Sys1p. Nat Cell Biol 6:414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemorry A, Hwang CS, Varshavsky A. 2013. Control of protein quality and stoichiometries by N‐terminal acetylation and the N‐end rule pathway. Mol Cell 50:540–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders Blok L, Madsen E, Juusola J, Gilissen C, Baralle D, Reijnders MR, Venselaar H, Helsmoortel C, Cho MT, Hoischen A, Vissers LE, Koemans TS, et al. 2015. Mutations in DDX3X are a common cause of unexplained intellectual disability with gender‐specific effects on Wnt signaling. Am J Hum Genet 97:343–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevenon J, Duffourd Y, Masurel‐Paulet A, Lefebvre M, Feillet F, El Chehadeh‐Djebbar S, St‐Onge J, Steinmetz A, Huet F, Chouchane M, Darmency‐Stamboul V, Callier P, et al. 2016. Diagnostic odyssey in severe neurodevelopmental disorders: towards clinical whole‐exome sequencing as a first‐line diagnostic test. Clin Genet. 10.1111/cge.12732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PR, Wang D, Wang L, Fulco M, Pediconi N, Zhang D, An W, Ge Q, Roeder RG, Wong J, Levrero M, Sartorelli V, et al. 2004. Regulation of the p300 HAT domain via a novel activation loop. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11:308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme P, Stove SI, Glomnes N, Gevaert K, Arnesen T. 2014. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae model reveals in vivo functional impairment of the Ogden syndrome N‐terminal acetyltransferase NAA10 Ser37Pro mutant. Mol Cell Proteomics 13:2031–2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweier C, Kraus C, Brueton L, Cole T, Degenhardt F, Engels H, Gillessen‐Kaesbach G, Graul‐Neumann L, Horn D, Hoyer J, Just W, Rauch A, et al. 2013. A new face of Borjeson‐Forssman‐Lehmann syndrome? De novo mutations in PHF6 in seven females with a distinct phenotype. J Med Genet 50:838–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Disclaimer: Supplementary materials have been peer‐reviewed but not copyedited.

Figure S1. Amino acid sequence of NAA10 orthologues. (A) Arg83 is highly conserved through evolution. In A. thaliana and S. pombe the arginine is substituted with either a lysine or histidine, both of which has a positively charged side chain and encompasses many of the same properties as an arginine. Similarly, Phe128 is highly conserved. In A. thaliana, this phenylalanine is substituted with the highly similar tyrosine residue. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of all the known catalytic NAT‐subunits. Similarly as in (A) both Arg83 and Phe128 are mostly conserved, suggesting that these amino acids have a functional role in the Naa10 enzyme. *, Val107, affected by the previously published p.(Val107Phe) mutation [Popp et al., 2015].

Figure S2. Elution profile from the size‐exclusion step of NAA10 purification. NAA10 p.(Phe128Leu) mostly elutes in the void volume of the superdex 200 column, suggesting that this protein forms aggregates or multimers larger than 200 kDa in size (tetramer or higher). Fractions of monomeric NAA10 were collected and used for in vitro acetylation assays.

Figure S3. (A) Determination of kinetic constants for NAA10 wild type and NAA10 p.(Arg83Cys). Enzymes were mixed with 500 μM oligopeptide and Ac‐CoA ranging from 10 μM to 1mM. Kinetic constants were determined by GraphPad Prism 6 and are summarized in (B).

Table S1. Genomic positions of mutations

Table S2. in silico prediction of mutations