Abstract

Commercial chromatographic instrumentation for bottom-up proteomics is often inadequate to resolve the number of peptides in many samples. This has inspired a number of complex approaches to increase peak capacity, including various multidimensional approaches, and reliance on advancements in mass spectrometry. One-dimensional reversed phase separations are limited by the pressure capabilities of commercial instruments and prevent the realization of greater separation power in terms of speed and resolution inherent to smaller sorbents and ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography. Many applications with complex samples could benefit from the increased separation performance of long capillary columns packed with sub-2 µm sorbents. Here, we introduce a system that operates at a constant pressure and is capable of separations at pressures up to 45 kpsi. The system consists of a commercially available capillary liquid chromatography instrument, for sample management and gradient creation, and is modified with a storage loop and isolated pneumatic amplifier pump for elevated separation pressure. The system’s performance is assessed with a complex peptide mixture and a range of microcapillary columns packed with sub-2 µm C18 particles.

Keywords: UHPLC, capillary chromatography, LC-MS, proteomics, peptides

1. Introduction

Understanding protein expression in biological systems is essential to elucidate the mechanism of disease, but complicated by the myriad of proteins within cells and the large range of abundances (greater than 1010) [1,2]. To mitigate the complexity of these samples, analytical methods often rely on reversed phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) separations prior to identification by the mass spectrometry (MS) [3]. However, because protein separations are plagued by low fragmentation and ionization efficiencies as well as sample carry over, many experiments begin with a proteolytic digestion before the separation [4–7]

Single-dimension separation techniques do not currently exhibit peak capacities high enough for complete resolution of the entire proteome and require MS detection to resolve many species in a single scan [8]. Although MS continues to develop, and improvements have been made in both acquisition rates and limits of detection, an initial separation remains critical. Even with developments including nano-ESI [9–12], ion mobility [13], and programs developed by bioinformaticians to aid in identification [14], the most advanced proteomic workflows still cannot map an entire proteome with a single analysis of even simple organisms such as yeast [15]. Development of more efficient liquid chromatographic (LC) techniques will allow for more fully resolved analytes to be introduced to the mass spectrometer and increase peptide and protein identifications.

The efficacy of an LC gradient separation, as described by the peak capacity, is defined as the maximum number of components that can be resolved within a given separation window. This can be increased by extending the gradient time but will ultimately plateau as gradients become shallow [16]. Alternatives to modification of gradient conditions to increase peak capacity include improving the column’s performance. Furthermore, microcapillary columns benefit the quality of analysis by increasing signal intensity, which is inversely proportional to the column’s internal diameter (id) squared (assuming constant sample volume) [17]. This is particularly important to proteomic experiments where samples are limited and/or analytes are in low abundance [11,12]. More fundamentally, peak capacity is proportional to the square root of column length for a given particle diameter (dp) and it is inversely proportional to the square root of dp at a given column length assuming all parameters of the gradient separation are constant [17,18].

Much in the way of efficiency can be gained from changes in a column’s length or packing sorbent. These options are little explored as the pressures needed to maintain a given reduced linear velocity increases proportionally to column length and inversely to the dp cubed [19]. Thus, the relatively low maximum pressure of commercially available systems has restricted use of long ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) columns packed with sub-2 µm particles. This has severely limited applications that would greatly benefit from enhanced separation power inherent to UHPLC prior to MS analysis.

Several manufactures produce LC systems capable of delivering nanoflow gradients at pressures up to 22kpsi. Smith and coworkers have demonstrated a non-commercial system capable of 20 kpsi with 40 to 200 cm × 50 µm id columns packed with 1.4–3 µm particles. These separations reported peak capacities ranging from 1000–1500 in 400–2000 minutes [20].

To date, even the highest performing commercial UHPLC systems cannot achieve peak capacities sufficient for proteomic samples [8]. Various multidimensional separation approaches have been explored to accommodate this and often implement an RPLC separation in the last dimension. It is expected that development of an instrument with elevated pressure capabilities will improve the efficacy of the final dimension in these methods as well.

A constant flow LC system that operated above 40 kpsi was first developed by the Jorgenson group and produced peak capacities of 430 in one hour. However, the system’s nonlinear gradient profile instigated redesign [21]. Subsequent publications described a gradient LC system that would deliver preloaded gradients at constant pressures up to 50 kpsi [22]. Unfortunately this system was developed around a now obsolete prototype LC pump controlled by custom software. More importantly, the system’s minimum flow rate restrictions necessitated the use of a flow splitter in excess of 10:1 to deliver accurate and reproducible nanoflow. This design diverted a portion of the sample volume along with a majority of the gradient to waste [23].

Gritti and Guichon [24] compared gradients delivered by constant pressure and constant flow and found that peak capacities were similar for both modes. Interestingly, peak capacity from the constant pressure mode showed a slight advantage as the system always operates at the maximum pressure and flow rate. While constant flow mode is limited by the pressure associated with the maximum viscosity of the mobile phase in the column [25]. Performing gradient separations at constant pressure is attractive as the analysis time is sped up, thereby increasing throughput [26,27]. A disadvantage to constant pressure systems depends on the quantitation aspects of mass-sensitive detectors with a nebulizing interface, such as ESI, where the varying flow rate can contribute to a reduction in nebulizer efficiency [28].

Herein, we describe a new constant pressure LC system capable of delivering split-less nanoflow gradients at pressures up to 45 kpsi. This automated system is built around a modified, commercially available, nanoAcquity and is controlled by MassLynx software. The instrument is capable of high-pressure separations and built with primarily “off-the-shelf” commercial parts. High peak capacities were achieved with long columns packed with sub-2 µm particles for a standard peptide mixture separation with this UHPLC system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Solvents and chemicals

Optima grade water + 0.1% formic acid, Optima grade acetonitrile +0.1% formic acid, L-ascorbic acid, hydroquinone, and acetone were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). All chemicals were ACS reagent grade or higher. MassPREP™ Digestion Standard Protein Expression Mixture 2 and enolase digestion standard were obtained from Waters Corporation (Milford, MA).

2.2 Instrumentation hardware

Hardware including valves, ferrules, nuts, connector-tees, unions and stainless steel tubing were purchased from Valco Instrument Co. (Houston, TX). Nano-tees were obtained from Waters Corporation, and fused silica capillary tubing was purchased from Polymicro Technologies, Inc. (Phoenix, AZ). The outer diameter for all capillary tubing was 360 µm.

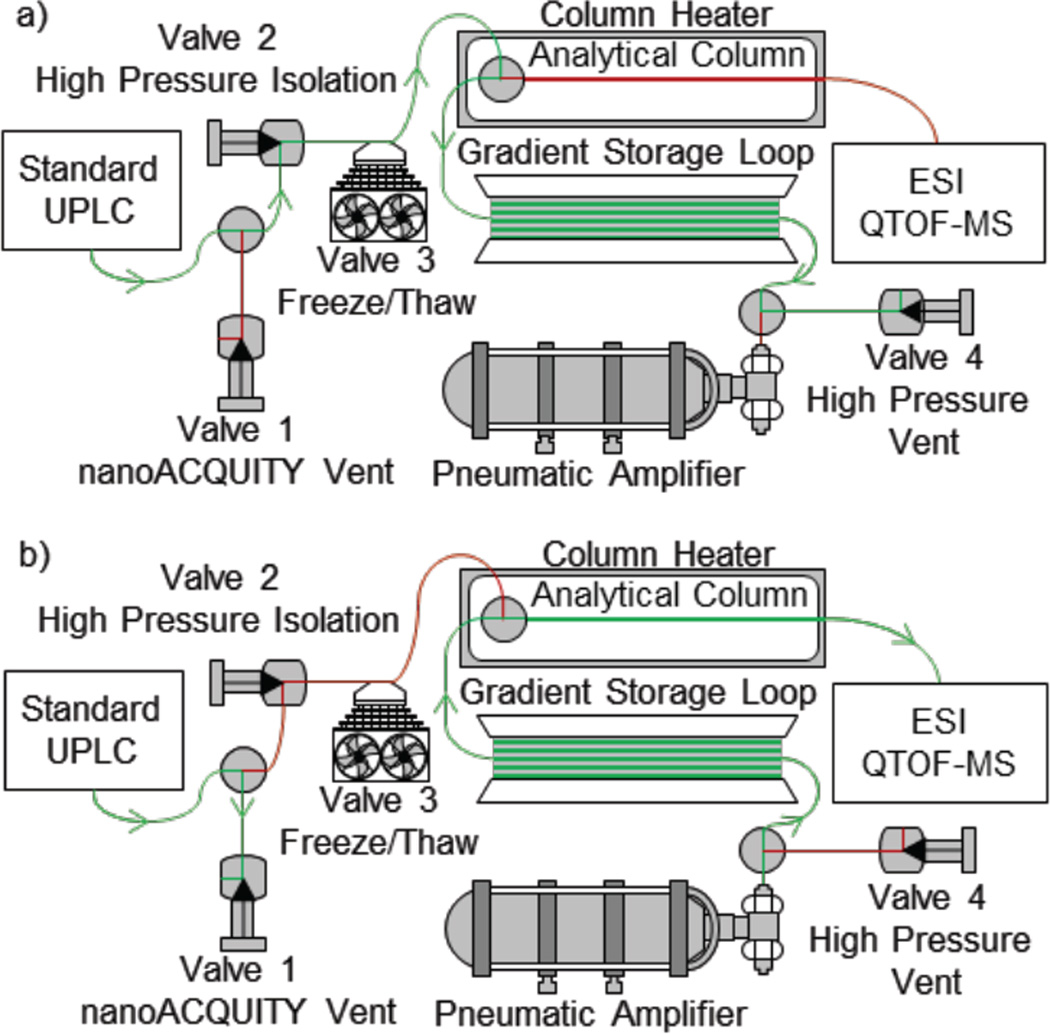

The chromatographic system was built around a nanoAcquity (Waters Corp.) as depicted in Figure 1. A 30 cm long piece of 50 µm id fused silica capillary tubing connected the sample manager injection valve to a nano-tee which split flow to Valve 1 (10 kpsi on/off) and Valve 2 (40 kpsi on/off). Valve 1 (the nanoAcquity vent) was incorporated as a safety measure against failure of Valve 2, which isolates the nanoAcquity from the high pressure pneumatic amplifier pump. All connections described to this point were made with a PEEK ferrule and a 1/32” nut. From Valve 2, a 60 cm length of 50 µm id fused silica capillary tubing was directed through a freeze/thaw valve (Valve 3) and to a second nano-tee. The freeze/thaw valve, developed by Dourdeville [29], was added to the system because valve 2 failed to reliably block all flow at pressures above 30kpsi. A 4-stage, stacked Peltier device drove freezing. A dual-output linear power supply by way of a double-pole, double-throw relay drove the direction of the heating and cooling configuration. The output voltage from the power supply was adjusted for Valve 3 to reach −55°C in the freeze state and 7°C in the thaw state. At the second nano-tee, the analytical column and gradient storage loop were joined to Valve 2. The gradient storage loop consisted of 10 m of 50 µm id silica capillary joined by a zero dead volume union to 40 m of 250 µm id stainless steel tubing. A third nano-tee connected the end of the storage loop to Valve 4 (40 kpsi on/off) and a 903:1 pneumatic amplifier pump, with a 75 kpsi pressure maximum (Haskel International Inc., Burbank, CA). Valve 4 served to vent the system after running at ultrahigh pressure. The pump was connected to the third nano-tee by 10 µm id fused silica capillary connected with a PEEK cylinder capillary compression fitting previously described [21]. All other high pressure connections were made with a PEEK ferrule and PEEK tubing compressed with a 1/32” nut, collet and collar. The 10 µm id fused silica capillary was selected to provide a flow limiter. If a large leak were to form farther down the fluidic network, most pressure would drop across this narrow id capillary. All valves were actuated through FET gates controlled by the on/off switches on the rear panel of the nanoAcquity.

Figure 1.

The nanoAcquity is shown with the additional tubing and valves necessary for separations at 45 kpsi. In loading mode (a), the gradient is formed by a standard UPLC and loaded on to the gradient storage loop. The sample injection is made by the autosampler on the standard UPLC and also loaded on to the storage loop. The valves are then actuated to isolate the standard UPLC from the ultrahigh pressure (b). The pneumatic amplifier pump drives the sample and gradient onto the analytical column at ultrahigh pressures. In both configurations, the green arrows indicate the direction of flow.

Analytical columns were packed in house and characterized with hydroquinone as previously described by the Jorgenson lab [19,21,30]. The packing material utilized was C18 modified bridged ethyl hybrid (BEH) (Waters Corp.). As particle size decreased column length was correspondingly decreased to maintain nano ESI compatible flow rates. The specifications for the columns used to characterize the system are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

The dimensions for each analytical column tested along with their measured flow rates and programmed gradient volumes.

| Column Length (cm) |

44.1 | 98.2 | 39.2 | 28.5 | |

| Internal Diameter (µm) |

75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | |

| Particle Diameter (µm) |

1.9 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.1 | |

|

Flow Rate (nL/min) | |||||

| Pressure | 15kpsi | 350 | - | - | - |

| 30kpsi | 730 | 330 | 410 | 370 | |

| 45kpsi | 1160 | - | - | - | |

|

Gradient Volume (µL) | |||||

| % Change in MPB Per Mobile Phase Volume |

4.0 | 14 | 31 | 12.5 | 8 |

| 2.0 | 28 | 62 | 25 | 16 | |

| 1.0 | 56 | 124 | 50 | 31 | |

| 0.5 | 113 | 249 | 100 | 62 | |

2.3 System Operation

The system operation procedure began with Valve 1 closed and Valves 2–4 open (Figure 1a). Mobile phase A (MPA) was Optima grade water with 0.1% formic acid and mobile phase B (MPB) was Optima grade acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. The desired gradient had a 4–40% B linear gradient followed by a 4 µL wash at 85% B and reequilibrium step at 4 % B. The gradient was loaded onto the storage loop in a last-in-first-out (LIFO) method. Loading was conducted at 5 µL/min with the high organic content first and low organic content last. Next, 1 µL of the sample was loaded with a push of 0.5% B at 5 µL/min. A total of 10 µL of mobile phase was required to push the sample out of the 1 µL injection loop, through the transfer tubing and onto the storage loop. Gradient volumes were determined experimentally from the columns elution time of L-ascorbic acid and the flow rate of 50:50 water:acetonitrile and programmed to produce a respective change in %B per column volume. After the gradient and sample were parked on the storage loop Valve 1 was opened, and Valves 2–4 were closed (Figure 1b.) After waiting 2.5 min for the mobile phase to freeze in the Peltier device, the pneumatic amplifier was engaged. The sample was pushed at high pressure from the storage loop onto the column and followed by the programmed gradient. The time needed prior to gradient playback (i.e. loading the gradient onto the storage loop, sample loading and changing states of the Peltier device) was around 5 min. The programmed method in Mass Lynx can be found in Supplemental Data Table 1.

2.4 Instrument characterization

Gradient profiles were measured by spiking mobile phase B with 10% acetone. The analytical column was replaced with a 55 cm × 5 µm id fused silica capillary and run at 30 kpsi. The flow of the capillary was directed to a Waters CapLC2489 UV/Vis Detector with a 75 µm bubble cell (Waters Corp.) and set to acquire data at 256 nm.

For system characterization with more complex samples, Standard Protein Expression Digestion Mixture 2 was run in duplicate for each chromatographic method. The outlet of the RPLC column was coupled to a qTOF Premier (Waters Corp.) via a 30 cm × 20 µm id fused silica capillary and a stainless steel nanospray emitter with a 20 µm id and a 10 µm tip (Waters Corp.). Spray voltage (+2.5 kV) was applied via electrical contact with the zero-dead-volume union in the nanosflow sprayer. Source temperature was 110°C and nanoflow was 0.4 bar. Data independent analysis, or MSE, was performed with a collisional energy ramp from 15–40 V. Scan time was set to 0.3 sec for the analysis of shorter gradients that produced sub-20 second wide chromatographic peaks. For longer gradients that produced wider peaks, the scan time was 0.6 sec. The interscan delay time was 0.1 sec in both cases.

LC-MS/MS data was processed using Protein Lynx Global Server 2.5 (Waters Corp.). The Standard Protein Expression Digestion Mixture 2 data were searched against a database of alcohol dehydrogenase, bovine serum albumin, glycogen phosphorylase b, and enolase. The amino acid sequences were found from the UNi-Prot protein knowledgebase (www.uniprot.org) and appended with a 1X reversed sequence. The false discover rate was set to 4%.

Peak capacity was determined from the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of each peptide identified in the ProteinLynx Global Server ion accounting output from the MassPREP™ Digestion Standard Protein Expression Mixture 2 sample. Two chromatograms were collected for each experimental condition. The data was then filtered to include only the 10 peptides that were detected in every analysis. The narrowed list included peaks of varying magnitude, covering the length of the retention window. The arithmetic mean of the FWHM measurements was then multiplied by 1.7 to yield 4σ peak width. The peak capacity was determined by dividing the separation window by 4σ peak width plus one. The separation window was the time between the elution of the first and last peak. To further analyze the peak widths, the median values and standard deviations are reported in Table 2. The median and mean values are very similar (<0.01 min in most cases). An example distribution of the data can be viewed in Supplemental Data Figure 1. The sample was sufficiently complex to have peak elution throughout the entire gradient length.

Table 2.

The average separation windows, peak widths (at 4σ), and peak capacities are listed for each column and applied gradient.

| Column Description |

Pressure (kpsi) |

Gradient Length (% Change in B per MP Volume) |

Separation Window (min) |

Average Peak Width (min) |

Median Peak Width (min) |

Standard Deviation of Peak Width (min) |

Peak Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 cm × 75 µm id 1.9 µm dp |

8 | 4 | 15 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 88 |

| 2 | 30 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 103 | ||

| 1 | 60 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0.07 | 161 | ||

| 0.5 | 120 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 0.09 | 191 | ||

| 44.1 cm × 75 µm id 1.9 µm dp |

15 | 4 | 35 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 264 |

| 2 | 69 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 385 | ||

| 1 | 132 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 455 | ||

| 0.5 | 275 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 596 | ||

| 30 | 4 | 18 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 174 | |

| 2 | 34 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 254 | ||

| 1 | 67 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 379 | ||

| 0.5 | 137 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 433 | ||

| 45 | 4 | 11 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 125 | |

| 2 | 24 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 174 | ||

| 1 | 47 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 269 | ||

| 0.5 | 93 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 344 | ||

| 98.2 cm × 75 µm id 1.9 µm dp |

30 | 4 | 90 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 457 |

| 2 | 180 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 622 | ||

| 1 | 360 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.05 | 773 | ||

| 0.5 | 720 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.12 | 877 | ||

| 39.2 cm × 75 µm id 1.4 µm dp |

30 | 4 | 34 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 246 |

| 2 | 60 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 352 | ||

| 1 | 123 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 366 | ||

| 0.5 | 240 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.09 | 566 | ||

| 28.5 cm × 75 µm id 1.1 µm dp |

30 | 4 | 22 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 174 |

| 2 | 38 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 220 | ||

| 1 | 70 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 309 | ||

| 0.5 | 125 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 352 |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Instrumental Design: gradient formation and dead volumes

Previous examples of UHPLC gradient systems have highlighted the difficulty of producing linear gradients at ultrahigh pressures [21]. The design of this instrument is based on a commercially available nanoAcquity UPLC that can accurately and reproducibly generate gradients to store prior to ultrahigh pressure operation [30,31]. This design allows for the gradient to merely be pushed and not formed at ultrahigh pressures. The preformed gradient is loaded onto the front of the storage loop in reverse order and played back in a LIFO workflow and has previously been described by Davis et al. for HPLC [32].

Traditional gradients are described in time. However, for a constant pressure system, gradients are more appropriately reported in units of volume. The gradient volume is directly calculated from the time it takes to load the gradient multiplied by the flow rate. The length of the gradient is programmed to produce a specific change in %B per column volume.

The reduction of total system dead volume is particularly important for generation of well-formed gradients as well as in the reduction of extra-column band broadening [33,34]. In this system dead volume between the storage loop and analytical column is limited to the 150 µm id bore through the tee connecting the storage loop to the column. Each arm of the tee is estimated to have a 21 nL cavity. Post-column dead volume from the connecting tubing and emitter tip was calculated to be 110 nL.

Although the pneumatic amplifier pump used in this system is capable of pressures reaching 75 kpsi, the system is limited by the robustness of the mechanical on/off valves that begin to leak at 30 kpsi.

3.2 Instrumental Design: gradient storage and loading

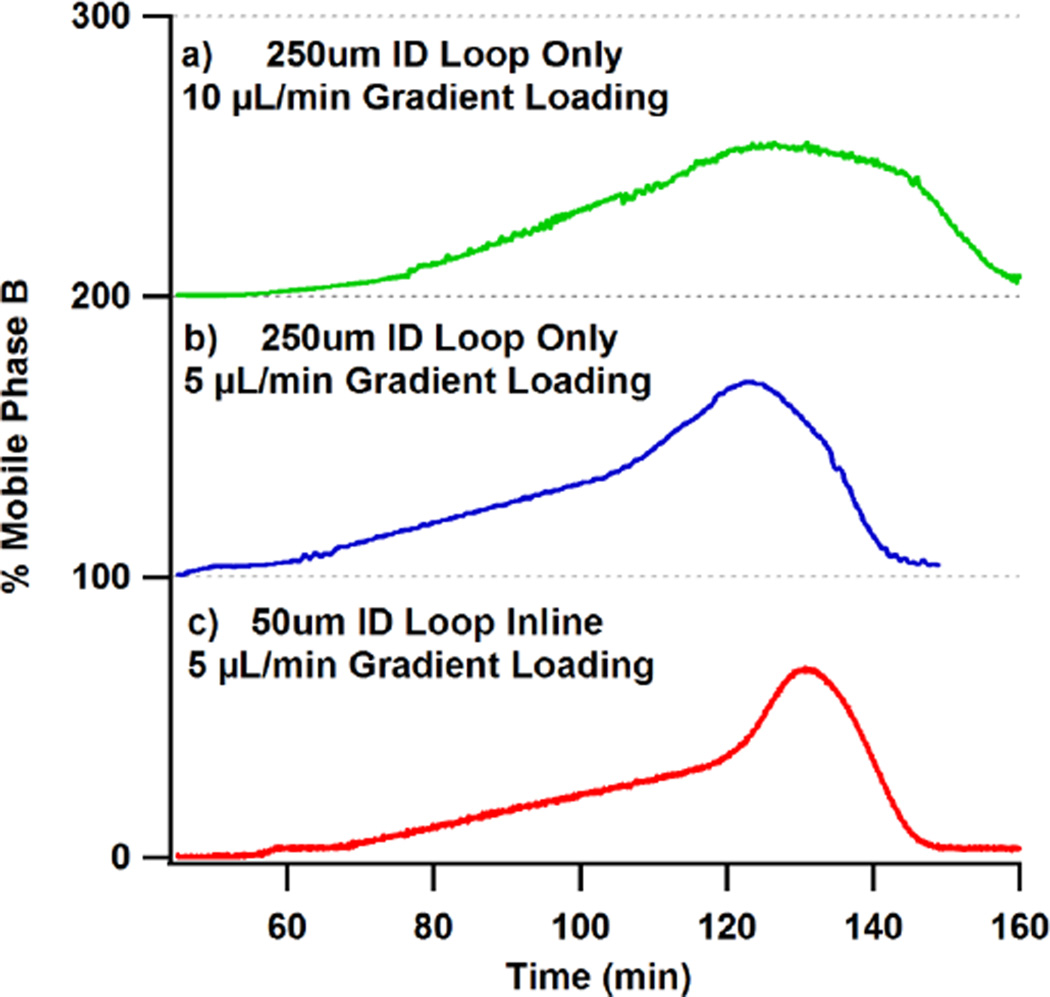

Effective implementation of the system requires accommodation of both long and short gradients to span a range of column lengths and particle sizes. The storage loop must accommodate appropriate gradient volumes as well as a narrow internal diameter to reduce Taylor-Aris mixing of the stored mobile phase [35]. Compromise must be made to balance the integrity of shorter gradients and the volume requirements of larger gradients. Thus, two storage loops were used in tandem. The first section consists of 10 m of 50 µm id silica capillary and stores 20 µL. The second section was 10 m of 250 µm id stainless steel tubing and stores 0.5 mL. An additional concern in gradient storage is the delivery of the gradient into the storage loop. Faster gradient loading flow rates will significantly decrease the integrity of the gradient shape.

Implementation of these two considerations is shown in Figure 2. Here a nonlinear gradient is produced when stored in a 250 µm id storage loop. In this example a 17 µL gradient should yield a 56 min long linear section from 4–40% B, which is proceeded by a 60 minute dwell time, and followed by a ramp to the 85% B wash. Faster loading flow rates caused mixing of the gradient and is clearly evident when comparison is made between Figure 2 a and b. Reduction of loading flow rate to 5 µL/min and the addition of the 50 µm id fused silica capillary produces a very linear, 56 minute long gradient and a distinct wash (Figure 2c). The playback of several gradient volumes can be found in Supplemental Data Figure 2a. Linearity of gradient playback time to volume loaded is further expounded in Supplemental Data Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

The gradient playback of the UHPLC instrument was monitored by the UV absorbance of acetone in mobile phase B. The mobile phase program started with an isocratic hold at 4%B followed by a 17 µL ramp from 4–40%B and concluded with a wash at 85%B and equilibration step. Flow rate for playback of the gradient was 300 nL/min. Figures 2a–c exhibit the effects of storage loop dimensions and gradient loading rate.

3.3 Column selection

Performance of this UHPLC instrument was assessed with capillary columns of varying length and several different sorbent sizes. 75 µm id was chosen to maintain flow rates compatible with nanoESI. All packed columns were evaluated prior to use with the gradient system by isocratic characterization to confirm similar performance. Most columns (the 39.2 cm, 1.4 µm dp, as well as the 44.1 cm and 92.2 cm, 1.9 µm dp) had an h-min below 2.0. The h-min of the 28.5 cm column was slightly greater and likely due to difficulties associated in packing of 1.1 µm particles [36]. Reduced van Deemter curves can be found in Supplemental Data Figure 3.

3.4 Retention time repeatability

To assess repeatability, the sample was analyzed once per day with a 12.5 uL gradient from 4–40%B run at 30 kpsi and 65 °C using the 110 cm × 75 µm, 1.9 µm dp column. The mean, standard deviation and relative standard deviations (RSD) were calculated from these results. The 17 tracked peptides had retention times with a 4.5% RSD or less. The relative retention times (RRT) was calculated by the retention time of a peak divided by the retention time of the peak corresponding to the peptide VNQIGTLSESIK. The RRT residual for each peptide was calculated as the RRT on a given day minus the average RRT. The arithmetic mean of the residuals was 3.4×10−4. The retention time repeatability data is presented in Supplemental Data Table 2 and Supplemental Data Figure 4.

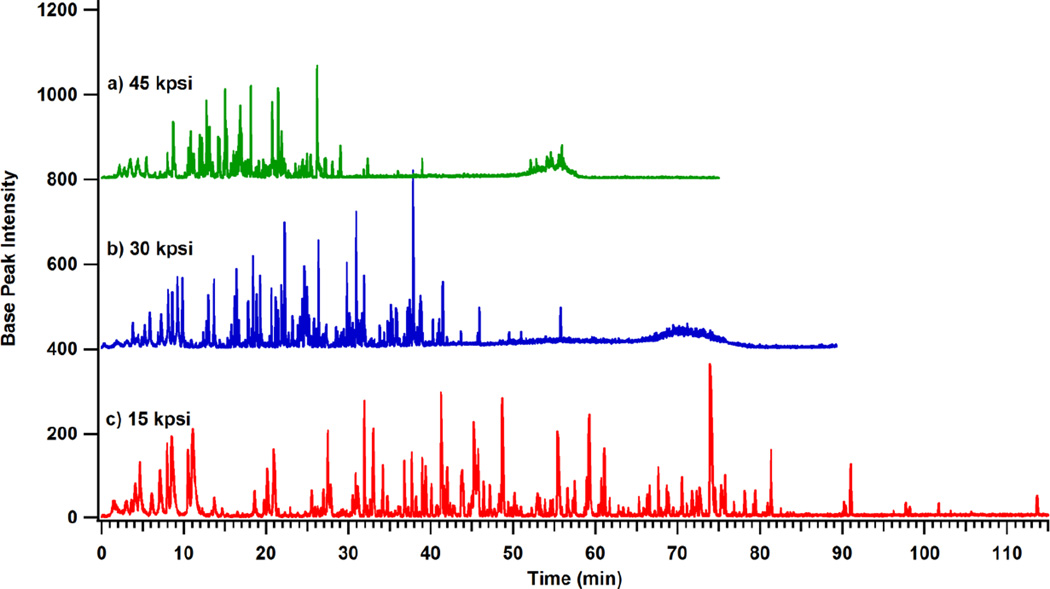

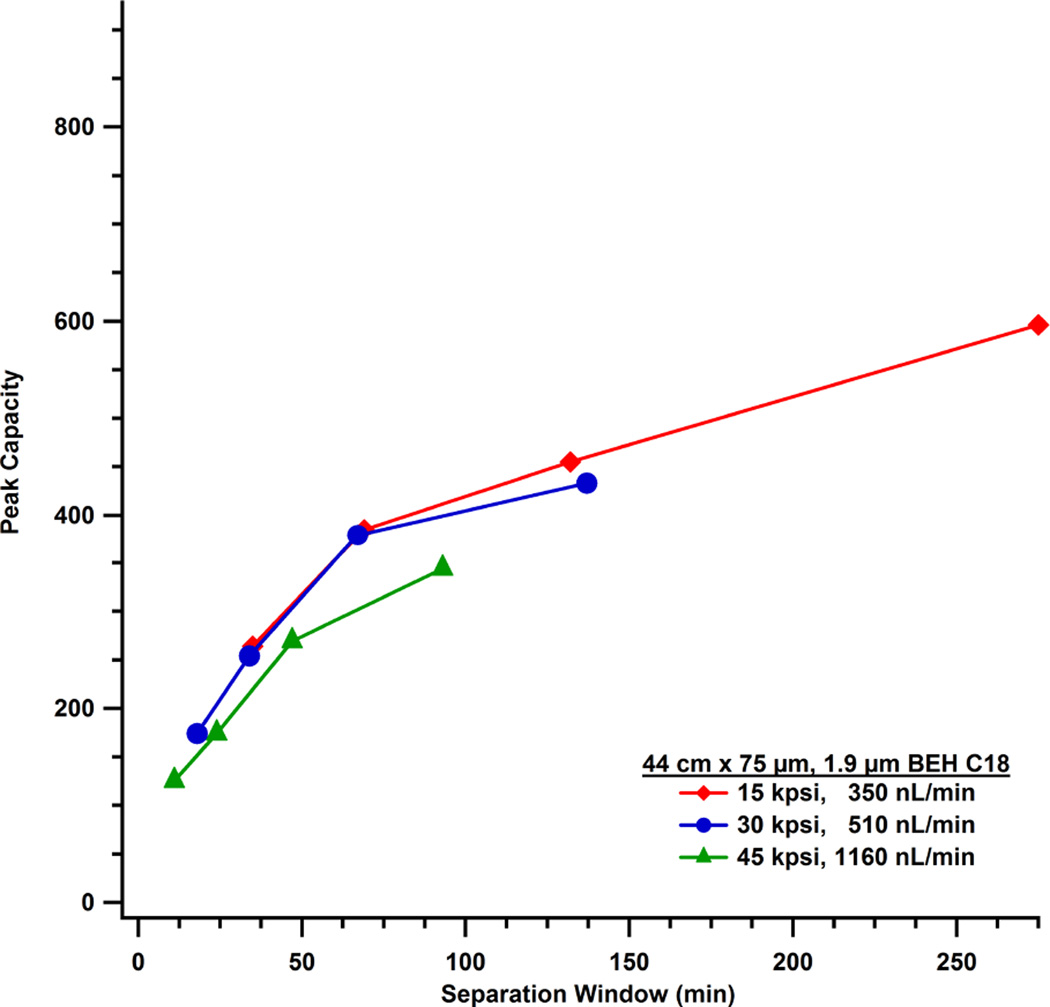

3.5 Separations at ultrahigh pressures and elevated temperatures

One benefit of operating at higher pressures is the ability to decrease the run time and still implement a shallow gradient. Example chromatograms are shown in Figure 3 of the standard protein digest separated on the 44.1 cm, 1.9 µm dp, column with a 56 µL gradient (corresponding to a 1% change in percent acetonitrile per column liquid fraction) at 15, 30 and 45 kpsi. Figure 4 plots peak capacity versus separation window for this column. At any given pressure, resolving power increases as the gradient volume is increased. Longer separation windows increase peak width and decreased peak height. This will ultimately affect the limit of detection. As illustrated in Figure 4, the peak capacity for the separation conducted at 45 kpsi plateaus at a lower value than for separations at 30 kpsi. The separation at 15 kpsi reaches a higher maximum peak capacity than higher-pressure separations, as the linear velocity was approximately 8 cm/min and close to the columns optimal velocity. At higher pressures and flow rates, the C-term contributes significantly to band broadening. Peak capacity data for each column under different gradient conditions is summarized in Table 2. Implementation of a longer column in the same study (e.g. three times the length but with similar efficiency) would result in an inverse trend in peak capacity as a function of run pressure from that presented in Figure 4. This is because a longer column would be operated closer to its optimal flow rate at 45 kpsi and severely hampered when operated at 15 kpsi.

Figure 3.

a–c. Chromatograms of MassPREP™ Digestion Standard Protein Expression Mixture 2 were collected for separations with decreasing pressure and flow rate on the 44.1 cm × 75 µm id column packed with 1.9 µm BEH C18 particles. Separations were completed with a 56 µL gradient volume.

Figure 4.

Peak capacity is plotted as a function of separation window for separations on a 44.1 cm × 75 µm id column with 1.9 µm BEH C18 particles. Each line represents a different pressure, and each point on a line (from left to right) represents the gradient profiles of 4, 2, 1, or 0.5 %change in MPB per mobile phase volume.

Though not required, the system was operated with the analytical column at 65 °C. Higher temperatures reduce the viscosity of the mobile phase and in turn allow for appropriate flow rates for even longer columns. Higher temperatures also reduce the relative change in mobile phase viscosity. As the gradient varied from 4–40% acetonitrile in water, the viscosity and flow rate would fluctuate by nearly 10% at 25°C. At 65°C this fluctuation is merely 5% [30,37,38]. Additionally, the resistance to mass transfer is reduced at high temperatures which causes flatter C-term regions of van Deemter plots and thus shifts to higher optimal velocities [39]. Analysis time is thereby reduced with mitigated loss in column efficiency [40].

3.6 Separations utilizing smaller particles

The elevated system pressure reported here provides research opportunity to explore particles that approach 1 µm dp. Importantly, high throughput laboratories will greatly benefit from the reduced run time associated with shorter columns packed with smaller particles as increased system pressure becomes more available. The analysis discussed herein did not increase throughput by increasing the number of runs per hour, but instead increases the number of peaks per minute. The time necessary for gradient loading and valve switching preclude the current design from being high-throughput in the traditional sense.

To assess the effects of smaller particles, columns were designed to produce flow rates near 300 nL/min at an applied pressure of 30 kpsi. These columns maintained a 75 µm id while column length was decreased to compensate for additional back pressure due to smaller sorbents.

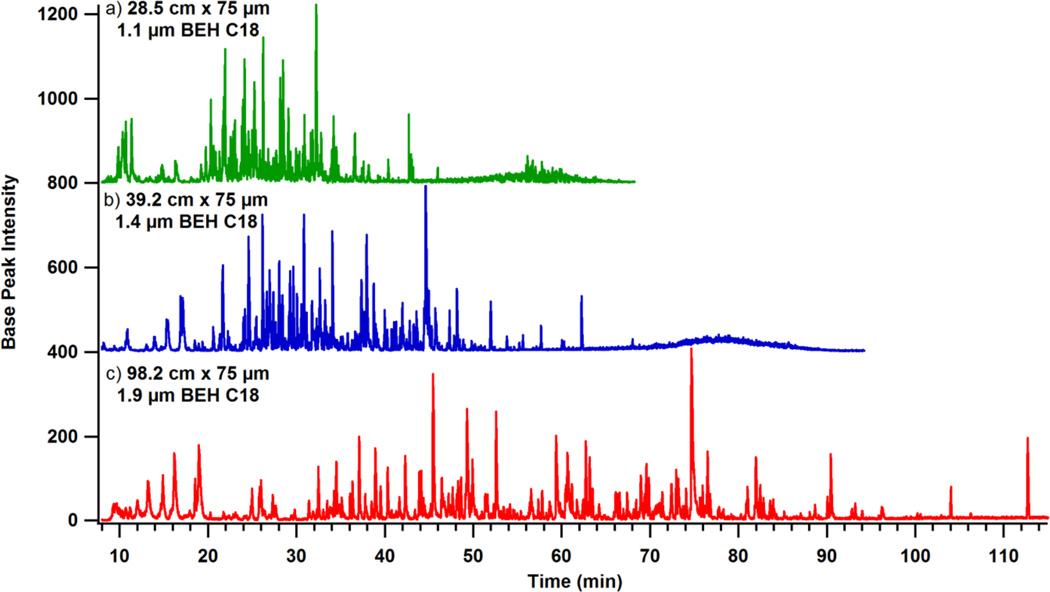

Example separations of the digest are shown in Figure 5a–c. Gradients were created with a similar 2% change per column volume in MPB. Figure 5 demonstrates how run time is affected when smaller particles are used and gradient steepness, operating pressure, and nominal flow rate are maintained.

Figure 5.

The standard protein digest was separated with a 16 µL gradient on a 28.5 cm × 75 µm id column packed with 1.1 µm BEH C18 particles (a, green), with a 25 µL gradient on a 39.2 cm × 75 µm id column packed with 1.4 µm BEH C18 particles (b, blue), and with 62 µL gradient on a 98.2 cm × 75 µm id column packed with 1.9 µm BEH C18 particles (c, red). The gradient volume corresponds to a 2% change in MPB per total mobile phase volume for each column. The chromatograms demonstrate how run time decreases when smaller particles are used and gradient steepness, operating pressure, and nominal flow rate are consistent.

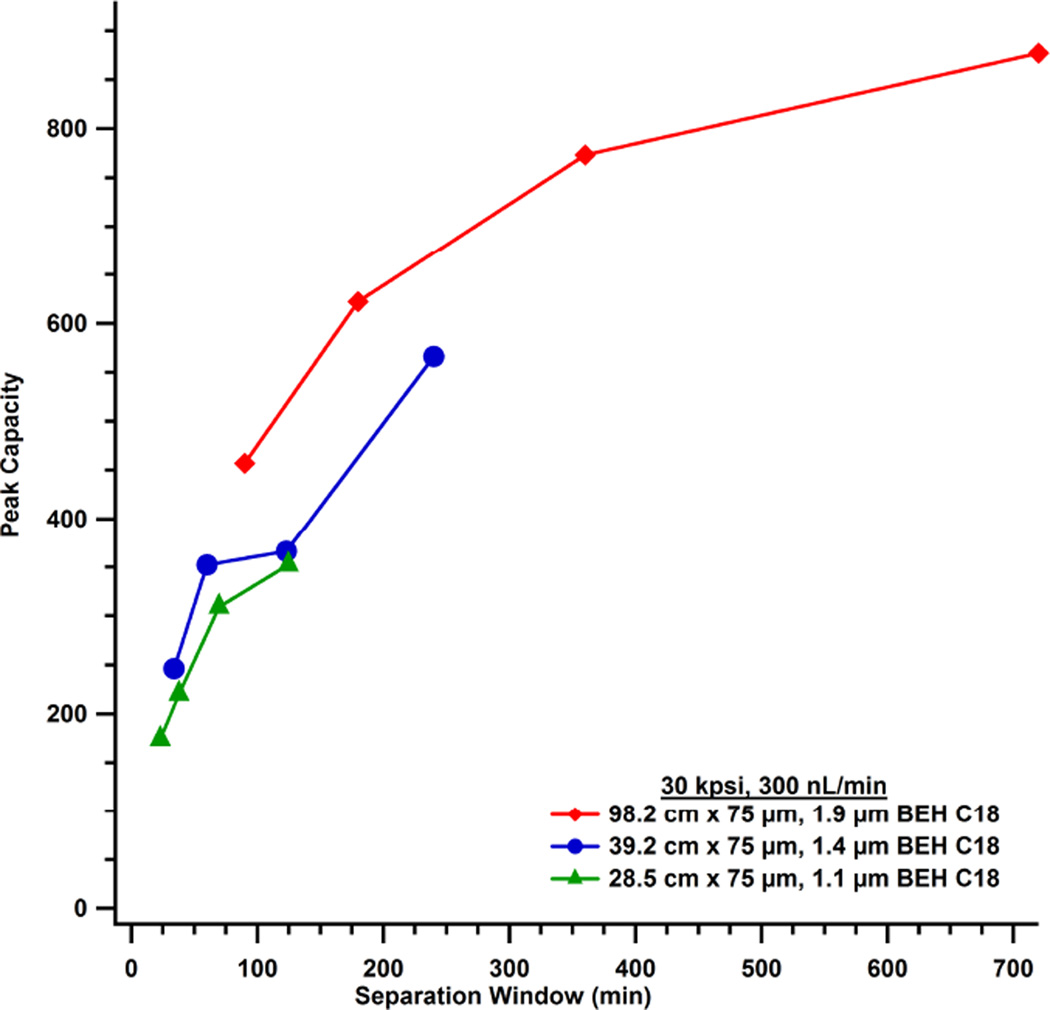

Figure 6 plots peak capacity as a function of separation window. For these three columns packed with varying particle sizes the highest peak capacities are achieved with the longest column and the largest dp. In this case, even short analysis times yielded higher peak capacities than shallower gradients with shorter columns. Pressure requirements are proportional to length and inversely proportional to dp cubed. Thus, length had to be sacrificed when running a column with smaller particles resulting in lower peak capacities.

Figure 6.

Peak capacity is plotted against separation window and illustrates the changes in performance for columns as a function of particle size. The colored line represents separations on each respective column as a function of change in %B per column volume

4. Conclusion

A gradient elution system with pressure capabilities up to 45 kpsi has been developed to improve the efficacy of one-dimensional separations. The system’s pressure capabilities of 45 kpsi allows for the implementation of a wide range of column parameters to capitalize on the benefits of fast and well resolved separations characteristic of UHPLC. Presented here are separations with very long columns packed with sub-2 µm particles that yielded peak capacities up to 877. These pressure capabilities were also utilized in the demonstration of fast and efficient separations on columns packed with sorbents nearing 1 µm. Increasing the pressure limits of gradient UHPLC platforms will directly impact the study of complex samples as more efficient and faster separations become more attainable with columns of more extreme dimensions.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Development of a constant pressure UHPLC gradient system

Development of a fully-automated constant pressure UHPLC gradient systemPeak capacities exceeding 800 for peptide separations

Gradient separations at 45 kpsi

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Waters Corporation (Milford, MA), the National Institute of Health (Grant #5U24DK097153) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (Grant #1R01DK101473-01A1) for support of this project. The authors would also like to thank Theodore Dourdeville for building the peltier freeze/thaw valve, Derek Wolfe for designing the switch control circuit and Keith Fadgen and Martin Gilar for insightful conversations regarding the project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Paik Y-K, Jeong S-K, Omenn GS, Uhlen M, Hanash S, Cho SY, Lee H-J, Na K, Choi E-Y, Yan F, Zhang F, Zhang Y, Snyder M, Cheng Y, Chen R, Marko-Varga G, Deutsch EW, Kim H, Kwon J-Y, Aebersold R, Bairoch A, Taylor AD, Kim KY, Lee E-Y, Hochstrasser D, Legrain P, Hancock WS. The Chromosome-Centric Human Proteome Project for cataloging proteins encoded in the genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:221–223. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson NL, Anderson NG. The Human Plasma Proteome History, Character, and Diagnostic Prospects. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2002;1:845–867. doi: 10.1074/mcp.r200007-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie F, Smith RD, Shen Y. Advanced proteomic liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 2012;1261:78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.06.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yates JR, Ruse CI, Nakorchevsky A. Proteomics by Mass Spectrometry: Approaches, Advances, and Applications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2009;11:49–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Washburn MP, Ulaszek R, Deciu C, Schieltz DM, Yates JR. Analysis of Quantitative Proteomic Data Generated via Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:1650–1657. doi: 10.1021/ac015704l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolters DA, Washburn MP, Yates JR. An Automated Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology for Shotgun Proteomics. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:5683–5690. doi: 10.1021/ac010617e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stobaugh JT, Fague KM, Jorgenson JW. Prefractionation of Intact Proteins by Reversed-Phase and Anion-Exchange Chromatography for the Differential Proteomic Analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Proteom. Res. 2012;12:626–636. doi: 10.1021/pr300701x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilar M, Olivova P, Daly AE, Gebler JC. Two-dimensional separation of peptides using RP-RP-HPLC system with different pH in first and second separation dimensions. J. Sep. Sci. 2005;28:1694–1703. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200500116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emmett MR, Caprioli RM. Micro-electrospray mass spectrometry: Ultra-highsensitivity analysis of peptides and proteins. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:605–615. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)85001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gale DC, Smith RD. Small volume and low flow-rate electrospray lonization mass spectrometry of aqueous samples. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1993;7:1017–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilm MS, Mann M. Electrospray and Taylor-Cone theory, Dole's beam of macromolecules at last? International J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Process. 1994;136:167–180. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilm M, Mann M. Analytical Properties of the Nanoelectrospray Ion Source. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:1–8. doi: 10.1021/ac9509519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valentine SJ, Plasencia MD, Liu X, Krishnan M, Naylor S, Udseth HR, Smith RD, Clemmer DE. Toward Plasma Proteome Profiling with Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry. J. Proteom. Res. 2006;5:2977–2984. doi: 10.1021/pr060232i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez-Galarza Faviel F, Lawless Craig, Hubbard Simon J, Fan Jun, Bessant Conrad, Hermjakob Henning, Jones Andrew R. A Critical Appraisal of Techniques, Software Packages, and Standards for Quantitative Proteomic Analysis. OMICS: J. Integr. Biol. 2012;16:431–442. doi: 10.1089/omi.2012.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hebert AS, Richards AL, Bailey DJ, Ulbrich A, Coughlin EE, Westphall MS, Coon JJ. The One Hour Yeast Proteome. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2014;13:339–347. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.034769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neue UD. Theory of peak capacity in gradient elution. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005;1079:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel KD, Jerkovich AD, Link JC, Jorgenson JW. In-Depth Characterization of Slurry Packed Capillary Columns with 1.0-µm Nonporous Particles Using Reversed-Phase Isocratic Ultrahigh-Pressure Liquid Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:5777–5786. doi: 10.1021/ac049756x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H, Finch JW, Lavallee MJ, Collamati RA, Benevides CC, Gebler JC. Effects of column length, particle size, gradient length and flow rate on peak capacity of nano-scale liquid chromatography for peptide separations. J. Chromatogr. A. 2007;1147:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacNair JE, Lewis KC, Jorgenson JW. Ultrahigh-Pressure Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography in Packed Capillary Columns. Anal. Chem. 1997;69:983–989. doi: 10.1021/ac961094r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen Y, Zhang R, Moore RJ, Kim J, Metz TO, Hixson KK, Zhao R, Livesay EA, Udseth HR, Smith RD. Automated 20 kpsi RPLC-MS and MS/MS with Chromatographic Peak Capacities of 1000–1500 and Capabilities in Proteomics and Metabolomics. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:3090–3100. doi: 10.1021/ac0483062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacNair JE, Patel KD, Jorgenson JW. Ultrahigh-Pressure Reversed-Phase Capillary Liquid Chromatography: Isocratic and Gradient Elution Using Columns Packed with 1.0-µm Particles. Anal. Chem. 1999;71:700–708. doi: 10.1021/ac9807013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Link JC. Development and application of gradient ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography for separations of complex biological mixtures. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eschelbach JW, Jorgenson JW. Improved Protein Recovery in Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography by the Use of Ultrahigh Pressures. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:1697–1706. doi: 10.1021/ac0518304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gritti F, Guiochon G. Theoretical comparison of the performance of gradient elution chromatography at constant pressure and constant flow rate. J. Chromatogr. A. 2012;1253:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.06.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gritti F, Stankovich JJ, Guiochon G. Potential advantage of constant pressure versus constant flow gradient chromatography for the analysis of small molecules. J. Chromatogr. A. 2012;1263:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Šesták J, Kahle V. Constant pressure mode extended simple gradient liquid chromatography system for micro and nanocolumns. J. Chromatogr. A. 2014;1350:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pauw RD, Desmet G, Broeckhoven J. Theoretical evaluation of the advantages and limitations of constant pressure versus constant flow rate gradient elution separation in supercritical fluid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013;1312:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verstraeten M, Broeckhoven K, Lynen F, Choikhet K, Landt K, Dittmann M, Witt K, Sandra P, Desmet G. Quantification aspects of constant pressure (ultra) high pressure liquid chromatography using mass-sensitive detectors with a nebulizing interface. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013;1274:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dourdeville TA. Waters Investments Limited, DE, Peltier based freeze-thaw valves and method of use. 7,128081 B2. US. 2006

- 30.Franklin EG. Utilization of Long Columns Packed with Sub-2 um Particles Operated at High Pressures and Elevated Temperatures for High-Efficiency One-Dimensional Liquid Chromatographic Separations. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stobaugh JT. Strategies for Differential Proteomic Analysis by Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis M, Stahl D, Lee T. Low flow high-performance liquid chromatography solvent delivery system designed for tandem capillary liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1995;6:571–577. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00192-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fountain KJ, Neue UD, Grumbach ES, Diehl DM. Effects of extra-column band spreading, liquid chromatography system operating pressure, and column temperature on the performance of sub-2-µm porous particles. J. Chromatogr. A. 2009;1216:5979–5988. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chesnut SM, Salisbury JJ. The role of UHPLC in pharmaceutical development. J. Sep. Sci. 2007;30:1183–1190. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200600505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aris R. On the Dispersion of a Solute in a Fluid Flowing through a Tube. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 1956;235:67–77. [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Villiers A, Lestremau F, Szucs R, Gélébart S, David F, Sandra P. Evaluation of ultra performance liquid chromatography: Part I. Possibilities and limitations. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1127:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H, Horváth C. High-speed high-performance liquid chromatography of peptides and proteins. J. Chromatogr. A. 1995;705:3–20. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(94)01254-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson JD, Carr PW. High-Speed Liquid Chromatography by Simultaneous Optimization of Temperature and Eluent Composition. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:4150–4159. doi: 10.1021/ac0112622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antia FD, Horváth C. High-performance liquid chromatography at elevated temperatures: examination of conditions for the rapid separation of large molecules. J. Chromatogr. 1988;435:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neue UD. HPLC Columns: Theory, Technology, and Practice. Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.