Abstract

ATPase H+-transporting lysosomal accessory protein 2 (Atp6ap2), also known as the (pro)renin receptor, is a type 1 transmembrane protein and an accessory subunit of the vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) that may also function within the renin-angiotensin system. However, the contribution of Atp6ap2 to renin-angiotensin-dependent functions remains unconfirmed. Using mice with an inducible conditional deletion of Atp6ap2 in mouse renal epithelial cells, we found that decreased V-ATPase expression and activity in the intercalated cells of the collecting duct impaired acid-base regulation by the kidney. In addition, these mice suffered from marked polyuria resistant to desmopressin administration. Immunoblotting revealed downregulation of the medullary Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter NKCC2 in these mice compared with wild-type mice, an effect accompanied by a hypotonic medullary interstitium and impaired countercurrent multiplication. This phenotype correlated with strong autophagic defects in epithelial cells of medullary tubules. Notably, cells with high accumulation of the autophagosomal substrate p62 displayed the strongest reduction of NKCC2 expression. Finally, nephron-specific Atp6ap2 depletion did not affect angiotensin II production, angiotensin II-dependent BP regulation, or sodium handling in the kidney. Taken together, our results show that nephron-specific deletion of Atp6ap2 does not affect the renin-angiotensin system but causes a combination of renal concentration defects and distal renal tubular acidosis as a result of impaired V-ATPase activity.

Keywords: Cell & Transport Physiology, cell biology and structure, acidosis, water-electrolyte, balance

The vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) is a multisubunit proton pump that participates in many cellular functions ranging from canonical roles, such as the primary active transport of protons across cell membranes, to noncanonical functions in signaling and membrane fusion.1,2 It consists of a V0 sector, responsible for proton translocation, and a V1 sector for ATP hydrolysis. Proton pump activity is essential for the degradation of macromolecules in the endolysosomal system. Moreover, autophagic degradation requires V-ATPase activity upon fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes. In the kidney, the V-ATPase controls several key functions, most notably systemic acid-base regulation. The α-intercalated cells (ICs) of the collecting duct (CD) express high amounts of V-ATPase at their apical surfaces to extrude protons into the urine.3 Accordingly, mutations in V-ATPase subunits can cause distal renal tubular acidosis.4

ATPase H+-transporting lysosomal accessory protein 2 (Atp6ap2) is an accessory V-ATPase subunit. Initially, it was found to coimmunoprecipitate with the V-ATPase in chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla.5 While this approach only identified an 8.9-kDa fragment, the full-length protein was cloned a few years later as a 37-kDa type 1 transmembrane protein.6 It was named (pro)renin receptor (PRR) because the extracellular domain was shown to bind renin and prorenin. The binding was proposed to lead to an increase of renin activity within the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) and to mediate RAS-independent (pro)renin signaling in diseases associated with high levels of (pro)renin.6,7 The discovery of Atp6ap2 understandably raised high expectations as a possible therapeutic target in hypertension and kidney disease. However, a number of observations elicited doubts about its actual physiologic function: first, gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments in rodents failed to show a convincing role in RAS and BP regulation8,9; second, studies with a peptide blocker of (pro)renin binding led to variable and also irreproducible effects in cell-based and animal models10–13; and finally, several in vitro and in vivo studies were beginning to uncover V-ATPase-associated functions for Atp6ap2.9, 14–17

Here, we have developed a kidney-specific, Atp6ap2 knockout mouse to more rigorously examine its organ-specific function and involvement in V-ATPase- and RAS-dependent functions. We show that Atp6ap2 is required for acid-base regulation in mice by controlling V-ATPase activity in ICs. In addition, mutant mice suffer from a marked urine concentration defect caused by a severe abnormality in lysosomal and autophagic clearance in thick ascending limb (TAL) cells and principal cells (PCs) of the CD. In contrast, tissue angiotensin II (AngII) production, AngII-dependent BP regulation and sodium handling were not affected by Atp6ap2 disruption. In conclusion, our studies demonstrate that the inducible conditional deletion of Atp6ap2 causes a variety of V-ATPase-dependent, but not RAS-dependent, defects along the nephron.

Results

Inducible Conditional Deletion of Atp6ap2 in the Nephron

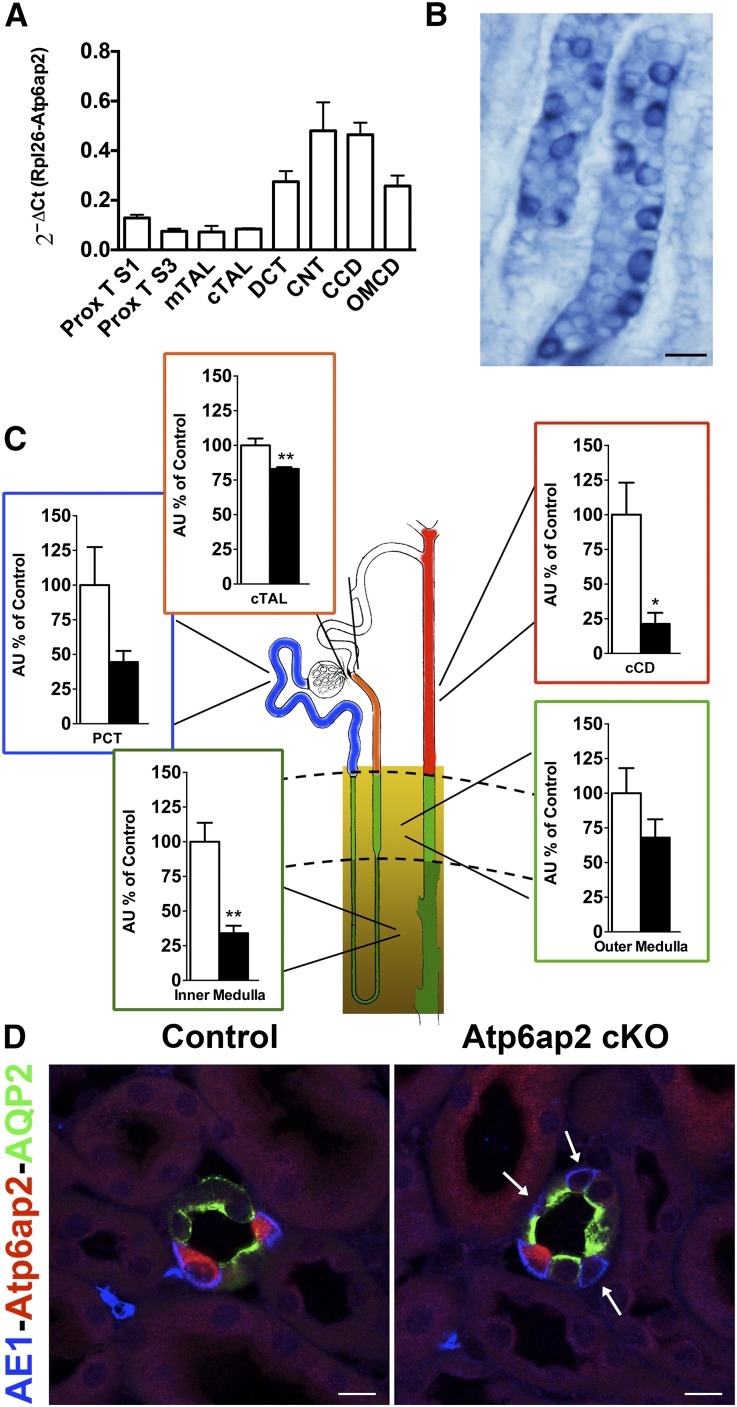

The expression pattern of the Atp6ap2 transcript along the nephron was first determined by quantitative RT-PCR on nephron segments isolated from adult mouse kidneys, as previously described.18 Figure 1A shows that Atp6ap2 mRNA was detected all along the nephron and CD system. The expression was highest in nephron segments known to be enriched for the V-ATPase, most notably in the connecting tubules and CDs. This was confirmed by in situ hybridization and immunostaining on kidney sections. With these methods, the most intense signal was detected in ICs of the CD (Figure 1, B and D).

Figure 1.

Atp6ap2 cKO mice show a significant reduction of Atp6ap2 expression. (A) Atp6ap2 mRNA expression along the nephron segments of wild-type mice (n=6 per nephron segment). (B) In situ hybridization of a renal section from a wild-type mouse incubated with riboprobes for Atp6ap2. A strong signal is observed in ICs of the CD. Scale bar: 20 µm. (C) Atp6ap2 mRNA quantification in isolated and dissected proximal tubules (PCT; n=3 control versus 3 cKO), cortical TAL (cTAL; n=4 control versus 5 cKO), cortical CD (cCD; n=3 control versus 3 cKO), and inner and outer medulla from control and Atp6ap2 cKO mice (n=4 control versus 5 cKO). (D) Representative pictures of triple staining with anti-AE1 (blue), anti-Atp6ap2 (red), and anti-AQP2 (green) antibodies of cryosections of control and Atp6ap2 cKO kidneys. Arrows mark the ICs with depletion of Atp6ap2. Scale bar: 10 µm. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; t test.

Based on this expression analysis, we decided to use the deleter line Pax8-Cre for Atp6ap2 depletion, which drives Cre expression along the entire renal tubule (except for glomeruli) in addition to minor expression in liver (Supplemental Figure 1).19 To circumvent any developmental defects associated with lack of Atp6ap2,20 the knockout was performed in an inducible manner by the combined use of the Tet-on and Cre/LoxP system (Pax8rtTA).19 Using RT-PCR on dissected tubules and regions from control and Atp6ap2 cKO kidneys (Figure 1C), we observed that Atp6ap2 mRNA was significantly downregulated in most parts of the nephron. In cortical CDs, the degree of knockout even reached up to 80%. We were not able to isolate individual medullary nephron segments, presumably because of renal fibrosis (see below). However, analysis of the renal inner medulla (IM) suggested that the deletion in the medullary CD was of the same magnitude as in cortical CDs. In agreement with the mRNA expression, immunostaining revealed that Atp6ap2 protein was ablated in many but not all ICs (Figure 1D).

Atp6ap2 cKO Exhibit Distal Renal Tubular Acidosis

Atp6ap2 cKO mice were born at normal Mendelian ratios with normal body weights. No morphologic abnormalities and normal papillary lengths were detected in mutant kidneys at the light microscope level (Supplemental Figure 2). However, Masson Trichrome staining of kidney sections from both 2- and 8-month-old mice revealed marked interstitial fibrosis. Fibrosis in the young animals was preferentially detected in the IM, while it extended progressively to the inner stripe of the outer medulla (ISOM) and the cortex in the older animals (Supplemental Figure 3).

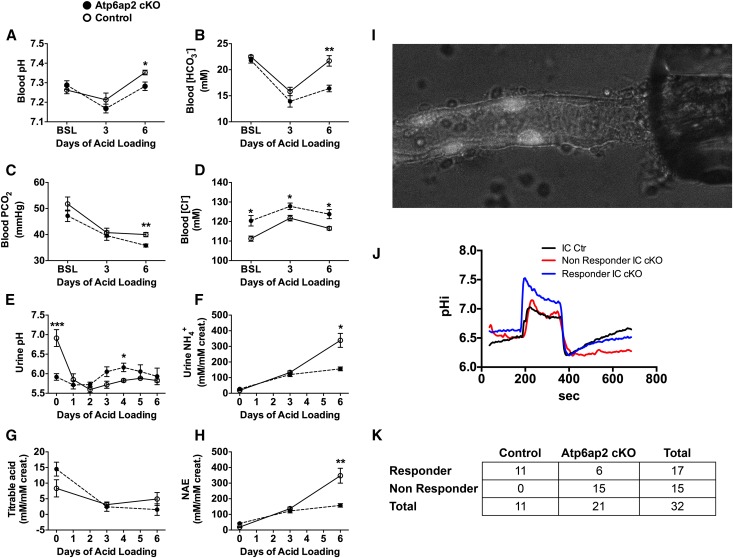

Atp6ap2 was initially identified as a putative subunit of the V-ATPase,21,22 and it is highly expressed in ICs. Therefore, we first analyzed whether Atp6ap2 cKO mice have impaired renal acidification. Data shown in Table 1 indicate that under baseline conditions, knockout and control animals exhibited the same values of blood pH, PCO2, and [HCO3–]. We next assessed the maximal ability of the mice to acidify urine by challenging them for 6 days with an acid load administered as a 0.3 M HCl-enriched diet. Figure 2 shows that after 3 days of acid loading, mice from both genotypes developed a similar degree of metabolic acidosis with respiratory compensation, as evidenced by decreased blood pH, PCO2, and [HCO3–]. When acid loading was continued, control mice were able to recover and exhibited normal blood pH and [HCO3–] at day 6 of the treatment. By contrast, a severe metabolic acidosis persisted in Atp6ap2 cKO mice (Figure 2, A and B). They were clearly unable to decrease their urine pH (Figure 2E). As a consequence, urinary ammonium and titrable acid excretion remained inappropriately low for an animal with metabolic acidosis (Figure 2, F–H). Next, we measured the transport activity of the V-ATPase in individual ICs using isolated perfused cortical CDs. Proton extrusion by the V-ATPase was analyzed as the recovery in sodium-free solutions of intracellular pH after an acute acid load. The results show that two different populations of ICs could be identified in CDs from Atp6ap2 cKO (Figure 2, J and K). The majority of ICs exhibited blunted V-ATPase-dependent proton extrusion. However, a subset of ICs showed normal intracellular pH recovery indicating normal V-ATPase activity. Of note, the respective fraction of cells with impaired (75%) or normal (25%) V-ATPase function was in accordance with the degree of Atp6ap2 deletion in ICs shown by immunostaining (Figure 1D). The acidification defect was not a result of inadequate IC differentiation,23 as reflected by normal numbers of total ICs (Supplemental Figure 4). However, the intensity of the labeling for the IC-specific V-ATPase subunit ATP6V1B1 was reduced in ICs of Atp6ap2 cKO mice, which was also confirmed by Western blotting of cortical and medullary membrane fractions (Supplemental Figure 5).

Table 1.

Blood and urine parameters

| Parameters | Unit | Control | n | Atp6ap2 cKO | n | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | ||||||

| pH | 7.29±0.01 | 14 | 7.30±0.01 | 13 | ||

| HCO3– | mM | 21.4±0.5 | 14 | 22.2±0.5 | 13 | |

| pCO2 | mmHg | 46±1.8 | 14 | 46±1.0 | 13 | |

| Na+ | mM | 148±0.4 | 16 | 150±0.5 | 13 | |

| K+ | mM | 4.66±0.08 | 14 | 4.38±0.04 | 11 | <0.01 |

| Cl- | mM | 111±0.48 | 17 | 120±1.26 | 12 | <0.01 |

| Ca2+ | mM | 1.26±0.01 | 17 | 1.25±0.01 | 13 | |

| Hb | g/dl | 13.8±0.2 | 17 | 13.1±0.3 | 13 | <0.05 |

| Ht | % | 42.4±0.57 | 17 | 40.2±0.79 | 13 | <0.05 |

| Urine | ||||||

| Output | µl/h per g body wt | 1.83±0.25 | 9 | 7.27±0.52 | 9 | <0.001 |

| Osmolality | mOsm/kg H2O | 2491±255 | 9 | 787±36 | 9 | <0.001 |

| pH | 6.72±0.1 | 9 | 6.09±0.14 | 8 | <0.01 | |

| PGE2 | pg/mM creatinine | 8.51±0.92 | 8 | 5.52±0.78 | 8 | <0.05 |

| ATP | nM/mM creatinine | 9221±1372 | 9 | 15128±3664 | 8 |

Figure 2.

Atp6ap2 cKO mice have distal renal tubular acidosis due to a defect in proton excretion in A-type ICs. (A–H) Time course of blood gas analysis (A–D) and urinary acid-base homeostasis parameters (E–H) from control (open circle) and Atp6ap2 cKO mice (black circle) during 6 days of acid load (HCl 0.3 M enriched food). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; t test. (I) Representative picture of a cortical CD loaded with BCECF. ICs appear brighter due to their ability to accumulate BCECF. (J) Representative profile of intracellular pH changes after an acute acid load (20 mM NH4Cl) in Atp6ap2 cKO mice. In Atp6ap2 cKO mice two response profiles for ICs were identified: the red curve represents cells unable to recover their intracellular pH after acidification; the blue curve represents cells with residual acid secreting ability. By contrast, all ICs from control mice properly recover from intracellular pH acidification (black curve). (K) R×C table of responder and nonresponder IC in control and Atp6ap2 cKO mice. Fischer exact test (P<0.001) shows that the number of nonresponder cells in Atp6ap2 cKO mice is significantly different from control mice.

These results strongly suggest that Atp6ap2 is an absolute requirement for normal V-ATPase expression and function, and explain why Atp6ap2 disruption in the kidney leads to distal tubular acidosis.

Atp6ap2 cKO Mice Suffer from Polyuria and Polydipsia

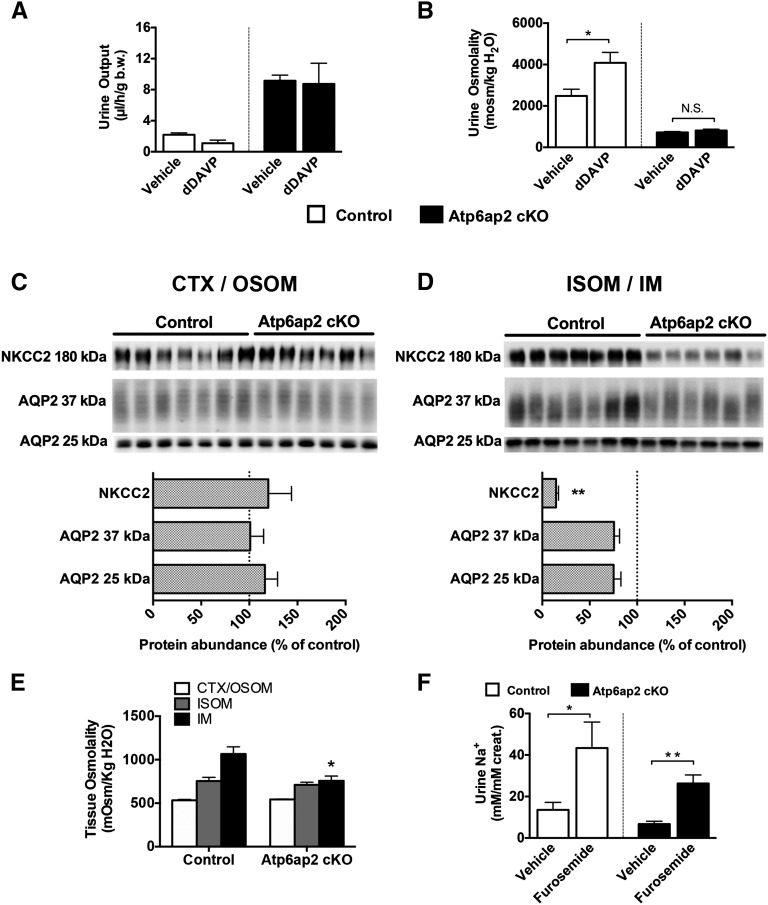

During our phenotyping, we noticed that under basal conditions, Atp6ap2 cKO mice presented with a four-fold higher urine volume than controls and exhibited strong polydipsia (average water intake =12.6 µl/h per g body wt versus 4.7 µl/h per g body wt for the control mice) (Figure 3, A and B, Table 1). Urine osmolality was markedly lower in Atp6ap2 cKO mice compared with controls (Figure 3B) and glucosuria was absent in mutant mice (data not shown). By contrast, slightly elevated values of plasma [Na+] were suggestive of abnormal renal water conservation. To confirm that the polyuria was not of central but of renal origin, we next tested the effects of acute administration of dDAVP, a pharmacological hormone that specifically activates the type 2 vasopressin receptor. Figure 3, A and B shows that Atp6ap2 cKO mice did not respond to dDAVP administration, while control mice were able to properly concentrate urine in response to the hormone, indicating that Atp6ap2 cKO mice exhibit a renal concentration defect.

Figure 3.

Atp6ap2 cKO mice are polyuric and have a defect in the mTAL. (A, B) Urine output (A) and osmolality (B) after 5 hours of dDAVP administration in control (white bars) and Atp6ap2 cKO mice (black bars; n=5 control versus 4 cKO). Asterisks indicate intragroup statistical differences. (C, D) Immunoblotting of NKCC2 and AQP2 along the nephron and their relative quantification (% of control). Lysates from cortex (CTX) and outer stripe of outer medulla (OSOM) are shown in C, and from inner stripe of outer medulla (ISOM) and IM in (D). **P<0.01; t test. (E) Tissue osmolality in samples from CTX/OSOM (white bars), ISOM (gray bars), and IM (black bars) from control and Atp6ap2 cKO mice. (F) Sodium excretion after 3 hours of intraperitoneal furosemide injection (2 mg/kg body wt) in control (white bars) and Atp6ap2 cKO mice (black bars; n=5 control versus 6 cKO; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test).

Polyuria is often observed in patients suffering from distal renal tubular acidosis type 1. Accordingly, we recently demonstrated that genetic disruption of Atp6v1b1 or pharmacological inhibition of the V-ATPase by bafilomycin causes an excessive release of extracellular ATP and PGE2 that can block water absorption by the adjacent PCs.24 However, ATP was not significantly increased and PGE2 was appropriately decreased in the urine of Atp6ap2 cKO mice ruling out the possibility that polyuria in this model is caused by abnormal paracrine signaling (Table 1).

Thus, to further analyze the cause of polyuria in our model, we assessed the protein abundance of the main two transporters for water handling, aquaporin 2 (AQP2) and NKCC2, by immunoblotting. We found that AQP2 was only slightly decreased in the renal medulla but not in the cortex of Atp6ap2 cKO kidneys (Figure 3 C and D). NKCC2 was strongly downregulated in the medulla but not in the cortex (Figure 3 C and D). Accordingly, Atp6ap2 knockout mice had a significantly lower osmolality in the IM but not in the other regions of the kidney compared with control mice (Figure 3E). As acute furosemide administration led to a normal natriuretic response in Atp6ap2 cKO mice, the NKCC2 expressed in TALs seemed to be functional (Figure 3F).

Taken together, the results indicate that Atp6ap2 cKO mice have significant medullary TAL dysfunction leading to an impaired establishment of the cortico-papillary gradient of interstitial osmoles. The resulting polyuria is probably further aggravated by the mild reduction of AQP2 we observed in the medullary CD.

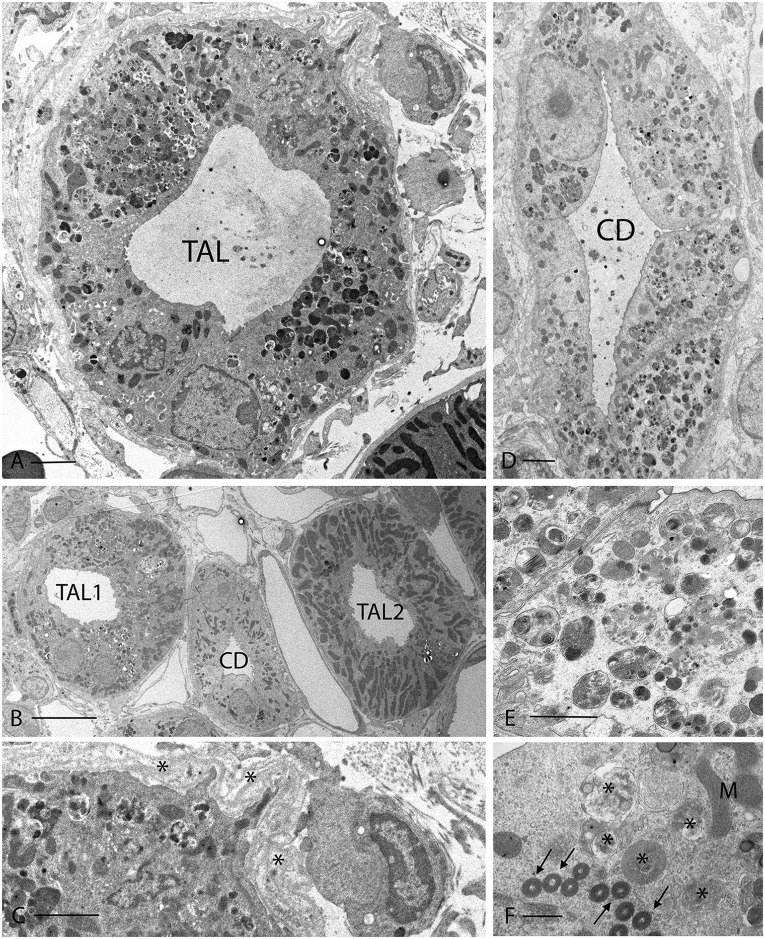

Lack of Atp6ap2 Leads to Autophagic Defects in Epithelial Cells with Downregulation of NKCC2 and AQP2

To identify the cellular defects causing the deranged water handling in Atp6ap2 cKO mice, we performed ultrastructural analysis. Transmission electron microscopy revealed a number of abnormalities in both 2- and 8-month-old mutant kidneys, particularly in the medulla (Figure 4, Supplemental Figure 6A). In many TALs and CDs, the epithelial cells contained large numbers of dense vesicular structures filled with undegraded cellular material (Figure 4, A, D, and E, Supplemental Figures 6 and 7), as well as numerous lamellar bodies (Figure 4F). As some of them also exhibited double membranes, the most likely explanation is that they represent autophagosomes. In line with the Masson Trichome staining, multilayered basement membranes and bundles of collagen fibers were detected around the tubules, along with increased interstitial cellularity (Figure 4, A and C, Supplemental Figure 6B). Generally, CDs and TALs in the IM were strongly affected (Figure 4, D and E), while the outer medulla was partly normal (e.g., TAL2 in Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Electron microscopy showing disrupted organization of cells in the TAL and CD of Atp6ap2 cKO mice. (A) TAL from the OSOM of an Atp6ap2 cKO kidney, in which most of the epithelial cells contain numerous autophagic vacuoles and other dense vacuoles of various sizes. (B) shows two TALs and a CD. TAL1 has a clearly damaged appearance with cells containing many autophagic vacuoles, while TAL2 looks relatively normal. The CD is mostly unaffected, but some PCs contain a few of the dense lamellar structures that are shown at higher magnification in panel F. (C) is a detail from panel A showing the abnormal multilamellar structure of the basement membrane that was typically seen around disrupted TALs (asterisks). See Supplemental Figure 6B for other examples of fibrosis around a TAL. (D) shows a CD from the initial third of the IM. All epithelial cells contain densely packed autophagic vacuoles. ICs were difficult to identify in such altered tubules in the medulla but they were easily detectable in unaffected tubules from these mice. These vacuoles are shown at higher magnification in panel E. (F) Some PCs contained numerous closely packed, dense lamellar bodies (arrows) along with more typical autophagosomes (asterisks). Scale bars: (A) 2 µm; (B) 10 µm; (C) 1 µm; (D) 2 µm; (E) 1 µm; (F) 0.5 µm. M, mitochondria.

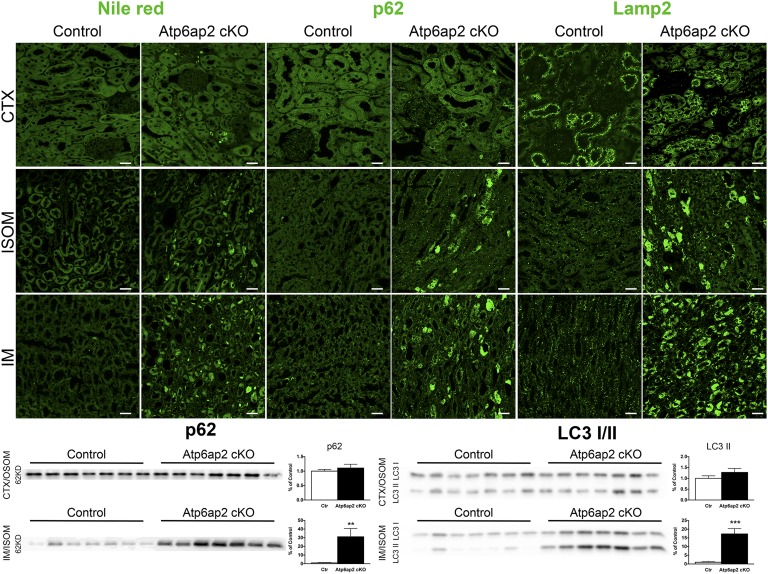

Next, we studied the autolysosomal system by immunohistochemistry. We found that lysosomal proteins, such as LAMP2, were strongly increased in Atp6ap2 cKO kidneys (Figure 5 and data not shown). As lysosomes depend on an intact autophagic system for turnover, lysosomal protein accumulation suggests impaired degradative capacity.25 Accordingly, Atp6ap2-deficient cells showed an accumulation of the autophagosomal substrate p62, also known as SQSTM1/sequestome 1. Interestingly, p62 accumulated in the IM and ISOM, but not in the cortex. Similarly, these regions of the nephron displayed high levels of lipid droplets, suggestive of downregulated autophagic lipid degradation or lipophagy (Figure 5).26 Confirming the immunostaining, immunoblotting showed an upregulation of p62 in the medulla but not the cortex of Atp6ap2 cKO kidneys. We further detected increased medullary levels of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3A (LC3)-I and–II, which supports the defect in autophagic flux (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Atp6ap2 cKO mice present autophagic defects in the renal medulla. Upper panel: representative images of renal CTX, ISOM, and IM sections stained with Nile Red (marker of lipid droplets), anti-p62 and anti-LAMP2 antibodies. Scale bar: 25 µm. Lower panel: expression of p62 or LC3 I/II in renal samples from CTX/OSOM and IM/ISOM. The quantification for p62 and LC3 II, respectively, is shown on the right side of the blots. **P<0.01; *** P<0.001; t test.

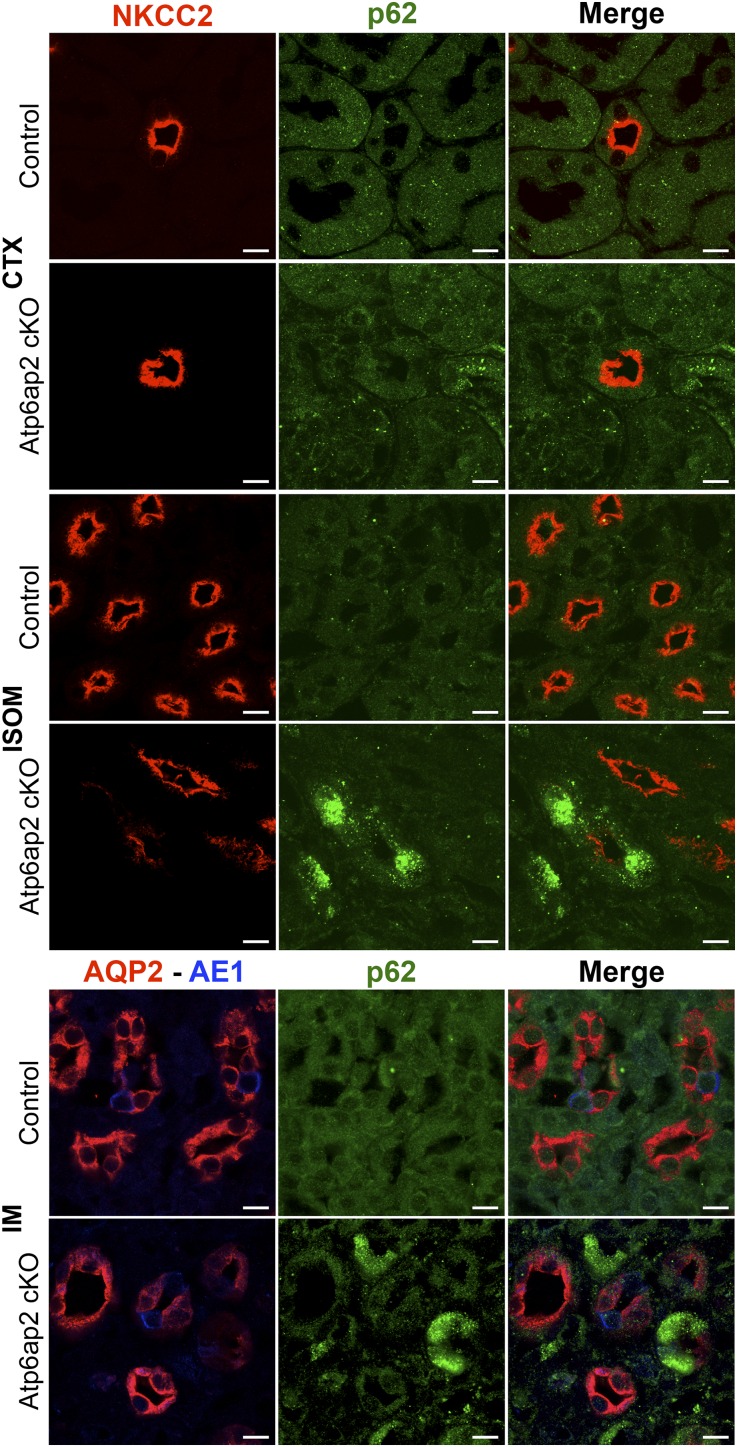

Finally, to identify whether the presence of autophagic defects correlated with the expression of ion transporters in medullary TAL and CD, double and triple labeling experiments were carried out. Indeed, we found that cells of the medullary but not cortical TAL with high levels of p62 showed a marked downregulation of NKCC2 expression (Figure 6). Furthermore, strong expression of p62 in cells coincided with reduced abundance of luminal AQP2 in medullary PCs (Figure 6). This was supported by immunogold labeling, showing little or no detectable AQP2 labeling of PCs with high numbers of autophagosomes, but normal levels of staining in cells with no autophagosomes (Supplemental Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Downregulation of NKCC2 and AQP2 correlates with autophagic defects in mTAL and mCD. Upper panel: representative images from renal CTX and ISOM from control and Atp6ap2 cKO mice stained with anti-NKCC2 (red) and anti-p62 (green) antibodies. Lower panel: representative images of IM from control and Atp6ap2 cKO mice stained with anti-AQP2 (red), anti-p62 (green), and anti-AE1 (blue) antibodies. Whereas cortical tubules are unaffected, damaged tubules (with p62 accumulation and downregulation of NKCC2 and AQP2, respectively) can be found alongside healthy tubules in the medulla. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Together, these findings suggest that a dysfunctional autophagy-lysosome system in a subset of medullary TAL and CD cells downregulates NKCC2 and AQP2, which most likely accounts for the urinary concentration defect in the mutant mice.

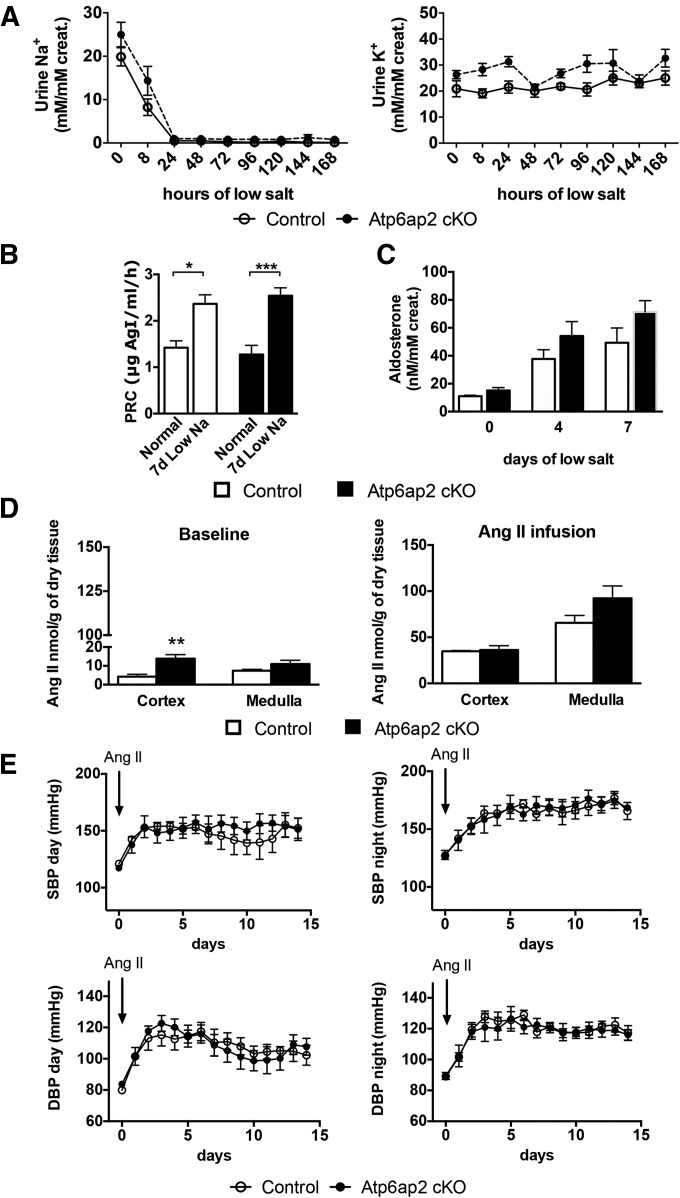

Lack of Atp6ap2 Does Not Affect AngII Production and AngII-Dependent BP Regulation

Atp6ap2 has been proposed to function as a PRR that facilitates the production of AngII.6 Given that one of the main renal effects of the RAS is the stimulation of renal sodium reclamation, which in turn drives potassium secretion, we first tested renal sodium and potassium handling under low salt conditions (0% Na+ in the diet). Control and Atp6ap2 cKO mice showed a similar natriuresis and kaliuresis profile. Moreover, plasma renin and 24-hour-urinary aldosterone concentrations were similar in both mice under basal conditions, as was the stimulation under low-salt conditions (Figure 7, A–C). Accordingly, the protein abundance of the two main sodium transporters of the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron, NCC and ENaC, were unchanged in the cortex and medulla, except for an increase of the ENaC γ-subunit in the medulla. The expression of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 was normal in the cortex and downregulated in the renal medulla (Supplemental Figure 8). As NHE3 is not only present in the proximal tubule but is also expressed in the TAL,27 this argues once again for a medullary TAL defect.

Figure 7.

Atp6ap2 cKO mice do not present with abnormal RAS and sodium balance. Time course of urinary sodium ([Na+]/[creatinine]) and potassium ([K+]/[creatinine]) excretion at 0, 8, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, and 168 hours of sodium restriction. (B) Plasma renin concentration (PRC) was measured under normal salt conditions (n=16 control versus 11 cKO) and after 7 days of NaCl restriction (n=6 control versus 6 cKO; *P<0.05; ***P<0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test). (C) Aldosterone ([Aldosterone]/[creatinine]) was measured in 24-hour urine collection at 0, 4, and 7 days of salt restriction diet (n=6 control versus 6 cKO; t test). (D) AngII concentration within cortex/OSOM and ISOM/IM at baseline (left; n=5 control versus 6 cKO) and after AngII infusion (right; n=4 control versus 4 cKO; t test). (E) Day and night systolic and diastolic BP was recorded by radiotelemetry over 15 days in control and Atp6ap2 cKO mice at baseline and under AngII subcutaneous infusion (1 µg/kg per min) (n=4 control versus 4 cKO; two-way ANOVA followed by a Student–Newman–Keuls post-test).

Next, we tested whether Atp6ap2 deficiency alters renin expression and AngII production. Kidney sections of control and Atp6ap2 cKO mice showed a similar staining intensity for renin. In both genotypes, renal renin expression was seen only in the juxtaglomerular apparatus. As a positive control, we used mice with disruption of the NaCl cotransporter NCC, which showed a clear increase in renin staining in the hyperplastic juxtaglomerular apparatus (Supplemental Figure 9). Local production of AngII was also comparable in Atp6ap2 cKO and control mice under basal conditions (Figure 7D). In the cortex, there was even an increased AngII production compared with control mice. We also measured cortical and medullary AngII after systemic AngII infusion (1 µg/kg per min), because this condition has been shown to stimulate the production of tissue AngII.28 Indeed, tissue AngII was significantly increased by systemic AngII infusion when compared with basal conditions. Yet, AngII concentrations were comparable in the renal medulla and cortex of the kidney from both genotypes, indicating that tissue AngII production is not affected by Atp6ap2 disruption (Figure 7D).

Finally, to rule out a role of Atp6ap2 in AngII-dependent BP regulation, we also monitored BP by radiotelemetry in Atp6ap2 cKO and control mice during AngII infusion over 15 days. AngII infusion led to a significant increase in day and night BP. However, both systolic and diastolic BP remained virtually identical in control and Atp6ap2 cKO mice (Figure 7E).

In summary, these results demonstrate that renal sodium handling as well as the intrarenal RAS are not affected by deletion of Atp6ap2.

Discussion

Our data suggest that the predominant phenotype of the conditional deletion of Atp6ap2 in the kidney is a strong impairment of V-ATPase activity. Reduced V-ATPase activity on the plasma membrane of ICs causes failure to adequately cope with acid stress. In addition, organellar V-ATPase dysfunction correlates with downregulation of a number of important ion transporters leading to a strong urinary concentration defect.

Similar phenotypes have already been detected when deleting Atp6ap2 from the ureteric bud, the developmental precursor of the CD system. This approach led to renal hypodysplasia and renal failure in the mice.20 However, the pathogenetic mechanisms were not extensively tested. In a very recent study, a urinary concentration defect was found using a similar Pax8-Cre–based approach as in the current study.29 Interestingly, reduced levels of medullary AQP2 and arginine vasopressin-induced cAMP were detected, which led the authors to speculate about AngII-dependent and -independent mechanisms in the control of AQP2 in PCs. Here, we could not detect a similar degree of AQP2 downregulation by Western blotting, but by immunostaining we observed a number of cells with high p62 expression and low AQP2 expression. This suggests that the autophagic defects are indeed causal for the dysregulation of ion transporter trafficking and turnover. Moreover, due to the central role of the V-ATPase in pathways regulating catabolism and cellular homeostasis, such as mTOR signaling,16,30 it can be speculated that epithelial organization and transport function is affected on multiple levels. The presence of fibrotic material and inflammatory cells surrounding many of the damaged tubules may cause further aggravation of the phenotype.

As Atp6ap2 is mainly expressed in ICs, the strong phenotype in TAL cells and PCs observed in our model is somewhat surprising. The situation is reminiscent of the podocytes, which also have low Atp6ap2 expression and display strong phenotypes in its absence.31,32 This suggests that Atp6ap2 levels need not be as high as in ICs in order for its loss to severely affect cell function. Another unexpected finding is that the cellular defects are strongest in the medulla. Our expression analysis and the use of a reporter mouse for Cre recombination suggest that heterogenous recombination rates may not be reason for the regional differences in Atp6ap2 depletion. Therefore, it is possible that different dynamics for autophagy exist along the cortico-medullary axis. Interestingly, Nunes et al. have demonstrated increased autophagy rates in cells treated with hypertonic medium.33 Because even in our knockout mice the medulla is more hypertonic than the cortex, there could indeed be different V-ATPase requirements in medullary epithelial cells compared with cortical cells. Thus, future studies should be performed to determine whether the hypertonic medulla renders epithelial cells more susceptible to autophagic defects.

The last decade has witnessed intense research on Atp6ap2 across disciplines. As a potential receptor for (pro)renin it held great promise as a novel druggable target within the RAS.34–36 Here, we provide evidence that, at least within the renal RAS of the mouse, a major role of Atp6ap2 seems unlikely. Despite significant Atp6ap2 depletion in our model, we show a lack of effect on (1) renin protein expression, (2) basal and AngII-stimulated local AngII production in the kidney, (3) AngII-dependent BP regulation, and (4) sodium and potassium handling by the nephron. What we cannot exclude at this point is that Atp6ap2 functions in RAS-independent renin signaling, mediating renal damage of increased renin levels, for example in ICs, smooth muscle cells, or mesangial cells.6,17 Nevertheless, we suggest that the term PRR should no longer be used to avoid confusion. In addition, the observed cell toxicity effects of Atp6ap2 depletion argue against the development of PRR inhibitors for the treatment of hypertension and kidney disease.

Concise Methods

Animal Experiments

To generate Atp6ap2 tubule-specific male knockout mice (PRRfx/Y; Pax8.rtTA;tetO.Cre), female Atp6ap2-floxed mice (PRRflox/flox, generously provided by Michael Bader) were crossed with male Pax8.rtTA;tetO.Cre mice. For the induction of Atp6ap2 deletion, pregnant female mice received doxycycline hydrochloride (Fagron) via the drinking water (2 mg/ml with 5% sucrose, protected from light) at embryonic day 16.5 (E16.5) up to birth (P0). At P0, doxycycline was replaced by normal drinking water. Mice were housed with a controlled temperature of 23°C, fed ad libitum with normal mouse chow, and under a 12-hour day/night cycle. Breeding and genotyping were performed using standard protocols. All animal experiments were conducted according to the German law governing the welfare of animals, and were approved by the Committee on Research Animal Care, Regierungspräsidium Freiburg (G-11/99). Animal procedures were also approved by the Departmental Director of ‘Services Vétérinaires de la Préfecture de Police de Paris' and by the ethical committee of the Paris Descartes University.

For urine collection, individual mice were studied in metabolic cages (Techniplast). After 3 days of adjustment, 24-hour urine output was collected under paraffin oil. Retro-orbital blood was sampled in isofluorane-anesthetized mice.

Quantitative PCR

Different nephron segments were manually dissected and total RNA was extracted with the RNAqueous-Micro Total RNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription was performed using random primers and the transcriptor first strand DNA kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green 1 kit was used to perform the quantitative PCR on a Lightcycler 480 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Immunoblotting

Cortex and ISOM/IM were manually dissected and then homogenized in ice-cold isolation buffer enriched with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), anti-phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and pepstatin A (1.5 µg/ml). Protein lysate preparation and immunoblotting procedures were performed as described previously.24 Quantification of each band was performed via densitometry using ImageJ.

Immunohistochemistry, In Situ Hybridization, and Electron Microscopy

Kidneys were fixed in situ by retrograde perfusion of the aorta with a solution of 4% PFA in phosphate buffer. Harvested kidneys were washed in ice-cold phosphate buffer for 30 minutes before freezing in cold isopentane. The antibodies used for immunohistochemistry are listed in Supplemental Material. Representative images were acquired with a Leica Confocal SP8 workstation.

In situ hybridization on thin sections was performed as described previously.37 Sense and antisense riboprobes for Atp6ap2 were prepared using the digoxigenin RNA labeling kit from Roche.

Transmission electron microscopy was performed using standard procedures. Ultrathin sections were cut on a Leica EMUC7 ultramicrotome, collected on formvar-coated grids, stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate, and examined in a JEOL 1011 transmission electron microscope at 80 kV. Images were acquired using an AMT (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA) digital imaging system.

Ex Vivo Microperfusion and Intracellular pH Measurements

Proton extrusion activity of ICs from isolated cortical CDs was measured as described previously.38

Statistical Analyses

Comparison among the two groups was performed by unpaired t test, unless differently stated. P value <0.05 was considered significant.

For a complete description of all the study methods, see Supplemental Material.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to G. Nguyen and M. Bader for providing the PRR floxed mice. We thank J. Löffing, C. Wagner, D. Ellison, P. Aronson, S. Frische, and the Develomental Studies Hybridoma Bank for providing antibodies. Sense and antisense riboprobes for Atp6ap2 were kindly provided by S. Arnold. We thank A. McDonough and J. Gianni for their help in establishing measurements of tissue angiotensin II. We thank Q. Al-Awqati for critically reading the manuscript. We are also grateful to C. Bravo, A. Mihoc, and E. Marot for animal care.

The work has been supported by the Fondation Bettencourt-Schüller, a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Emmy-Noether grant (SI1303/2-1) and an Action Thématique et Incitative sur Programme-Avenir grant to M.S., as well as grants from l’Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR; ANR BLANC 2012-R13011KK to R.C., and ANR BLANC 14-CE12-0013-01/HYPERSCREEN to D.E.). D.E. is also funded by grant CHLORBLOCK from the Initiative d'excellence Sorbonne Paris Cité. K.I.L. received a fellowship from the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica. F.T. received a fellowship from the European Renal Association - European Dialysis and Translpantation Association (LTF141-2013). T.B.H. is supported by the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments (EXC 294). D.B. and T.G.P. were supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK042956. Additional support for the Program in Membrane Biology Microscopy Core comes from the Boston Area Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center (DK57521) and the Massachussets General Hospital Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (DK43351).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015080915/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Maxson ME, Grinstein S: The vacuolar-type H⁺-ATPase at a glance - more than a proton pump. J Cell Sci 127: 4987–4993, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forgac M: Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 917–929, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown D, Hirsch S, Gluck S: An H+-ATPase in opposite plasma membrane domains in kidney epithelial cell subpopulations. Nature 331: 622–624, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breton S, Brown D: Regulation of luminal acidification by the V-ATPase. Physiology (Bethesda) 28: 318–329, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludwig J, Kerscher S, Brandt U, Pfeiffer K, Getlawi F, Apps DK, Schägger H: Identification and characterization of a novel 9.2-kDa membrane sector-associated protein of vacuolar proton-ATPase from chromaffin granules. J Biol Chem 273: 10939–10947, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen G, Delarue F, Burcklé C, Bouzhir L, Giller T, Sraer JD: Pivotal role of the renin/prorenin receptor in angiotensin II production and cellular responses to renin. J Clin Invest 109: 1417–1427, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez AA, Prieto MC: Renin and the (pro)renin receptor in the renal collecting duct: Role in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 42: 14–21, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosendahl, A, Niemann, G, Lange, S, Ahadzadeh, E, Krebs, C, Contrepas, A, van Goor, H, Wiech, T, Bader, M, Schwake, M, Peters, J, Stahl, R, Nguyen, G, Wenzel, UO: Increased expression of (pro)renin receptor does not cause hypertension or cardiac and renal fibrosis in mice. Lab Invest 94: 863–872, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinouchi K, Ichihara A, Sano M, Sun-Wada GH, Wada Y, Kurauchi-Mito A, Bokuda K, Narita T, Oshima Y, Sakoda M, Tamai Y, Sato H, Fukuda K, Itoh H: The (pro)renin receptor/ATP6AP2 is essential for vacuolar H+-ATPase assembly in murine cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 107: 30–34, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldt S, Maschke U, Dechend R, Luft FC, Muller DN: The putative (pro)renin receptor blocker HRP fails to prevent (pro)renin signaling. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 743–748, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sihn G, Rousselle A, Vilianovitch L, Burckle C, Bader M: Physiology of the (pro)renin receptor: Wnt of change? Kidney Int 78: 246–256, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batenburg WW, Lu X, Leijten F, Maschke U, Müller DN, Danser AH: Renin- and prorenin-induced effects in rat vascular smooth muscle cells overexpressing the human (pro)renin receptor: does (pro)renin-(pro)renin receptor interaction actually occur? Hypertension 58: 1111–1119, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller DN, Klanke B, Feldt S, Cordasic N, Hartner A, Schmieder RE, Luft FC, Hilgers KF: (Pro)renin receptor peptide inhibitor “handle-region” peptide does not affect hypertensive nephrosclerosis in Goldblatt rats. Hypertension 51: 676–681, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruciat CM, Ohkawara B, Acebron SP, Karaulanov E, Reinhard C, Ingelfinger D, Boutros M, Niehrs C: Requirement of prorenin receptor and vacuolar H+-ATPase-mediated acidification for Wnt signaling. Science 327: 459–463, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermle T, Guida MC, Beck S, Helmstädter S, Simons M: Drosophila ATP6AP2/VhaPRR functions both as a novel planar cell polarity core protein and a regulator of endosomal trafficking. EMBO J 32: 245–259, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gleixner EM, Canaud G, Hermle T, Guida MC, Kretz O, Helmstädter M, Huber TB, Eimer S, Terzi F, Simons M: V-ATPase/mTOR signaling regulates megalin-mediated apical endocytosis. Cell Reports 8: 10–19, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu X, Garrelds IM, Wagner CA, Danser AH, Meima ME: (Pro)renin receptor is required for prorenin-dependent and -independent regulation of vacuolar H⁺-ATPase activity in MDCK.C11 collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F417–F425, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eladari D, Cheval L, Quentin F, Bertrand O, Mouro I, Cherif-Zahar B, Cartron JP, Paillard M, Doucet A, Chambrey R: Expression of RhCG, a new putative NH(3)/NH(4)(+) transporter, along the rat nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1999–2008, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traykova-Brauch M, Schönig K, Greiner O, Miloud T, Jauch A, Bode M, Felsher DW, Glick AB, Kwiatkowski DJ, Bujard H, Horst J, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Niggli FK, Kriz W, Gröne HJ, Koesters R: An efficient and versatile system for acute and chronic modulation of renal tubular function in transgenic mice. Nat Med 14: 979–984, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song R, Preston G, Ichihara A, Yosypiv IV: Deletion of the prorenin receptor from the ureteric bud causes renal hypodysplasia. PLoS One 8: e63835, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Advani A, Kelly DJ, Cox AJ, White KE, Advani SL, Thai K, Connelly KA, Yuen D, Trogadis J, Herzenberg AM, Kuliszewski MA, Leong-Poi H, Gilbert RE: The (Pro)renin receptor: site-specific and functional linkage to the vacuolar H+-ATPase in the kidney. Hypertension 54: 261–269, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez AA, Luffman C, Bourgeois CR, Vio CP, Prieto MC: Angiotensin II-independent upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 by activation of the (Pro)renin receptor in rat renal inner medullary cells. Hypertension 61: 443–449, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Awqati Q: Terminal differentiation in epithelia: the role of integrins in hensin polymerization. Annu Rev Physiol 73: 401–412, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gueutin V, Vallet M, Jayat M, Peti-Peterdi J, Cornière N, Leviel F, Sohet F, Wagner CA, Eladari D, Chambrey R: Renal β-intercalated cells maintain body fluid and electrolyte balance. J Clin Invest 123: 4219–4231, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung YH, Chen LM, Yang JY, Yang WY: Spatiotemporally controlled induction of autophagy-mediated lysosome turnover. Nat Commun 4: 2111, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Cuervo AM, Czaja MJ: Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature 458: 1131–1135, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amemiya M, Loffing J, Lötscher M, Kaissling B, Alpern RJ, Moe OW: Expression of NHE-3 in the apical membrane of rat renal proximal tubule and thick ascending limb. Kidney Int 48: 1206–1215, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Seth DM, Satou R, Horton H, Ohashi N, Miyata K, Katsurada A, Tran DV, Kobori H, Navar LG: Intrarenal angiotensin II and angiotensinogen augmentation in chronic angiotensin II-infused mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F772–F779, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramkumar N, Stuart D, Calquin M, Quadri S, Wang S, Van Hoek AN, Siragy HM, Ichihara A, Kohan DE: Nephron-specific deletion of the prorenin receptor causes a urine concentration defect. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 309: F48–F56, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zoncu R, Bar-Peled L, Efeyan A, Wang S, Sancak Y, Sabatini DM: mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Science 334: 678–683, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riediger F, Quack I, Qadri F, Hartleben B, Park JK, Potthoff SA, Sohn D, Sihn G, Rousselle A, Fokuhl V, Maschke U, Purfürst B, Schneider W, Rump LC, Luft FC, Dechend R, Bader M, Huber TB, Nguyen G, Muller DN: Prorenin receptor is essential for podocyte autophagy and survival. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2193–2202, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oshima Y, Kinouchi K, Ichihara A, Sakoda M, Kurauchi-Mito A, Bokuda K, Narita T, Kurosawa H, Sun-Wada GH, Wada Y, Yamada T, Takemoto M, Saleem MA, Quaggin SE, Itoh H: Prorenin receptor is essential for normal podocyte structure and function. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2203–2212, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nunes P, Ernandez T, Roth I, Qiao X, Strebel D, Bouley R, Charollais A, Ramadori P, Foti M, Meda P, Féraille E, Brown D, Hasler U: Hypertonic stress promotes autophagy and microtubule-dependent autophagosomal clusters. Autophagy 9: 550–567, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Danser AH: The Role of the (Pro)renin Receptor in Hypertensive Disease. Am J Hypertens 28: 1187–1196, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prieto MC, Gonzalez AA, Navar LG: Evolving concepts on regulation and function of renin in distal nephron. Pflugers Arch 465: 121–132, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ichihara A, Suzuki F, Nakagawa T, Kaneshiro Y, Takemitsu T, Sakoda M, Nabi AH, Nishiyama A, Sugaya T, Hayashi M, Inagami T: Prorenin receptor blockade inhibits development of glomerulosclerosis in diabetic angiotensin II type 1a receptor-deficient mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1950–1961, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerber SD, Amann R, Wyder S, Trueb B: Comparison of the gene expression profiles from normal and Fgfrl1 deficient mouse kidneys reveals downstream targets of Fgfrl1 signaling. PLoS One 7: e33457, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leviel F, Hübner CA, Houillier P, Morla L, El Moghrabi S, Brideau G, Hassan H, Parker MD, Kurth I, Kougioumtzes A, Sinning A, Pech V, Riemondy KA, Miller RL, Hummler E, Shull GE, Aronson PS, Doucet A, Wall SM, Chambrey R, Eladari D: The Na+-dependent chloride-bicarbonate exchanger SLC4A8 mediates an electroneutral Na+ reabsorption process in the renal cortical collecting ducts of mice. J Clin Invest 120: 1627–1635, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.