Abstract

Hypercalciuria is a major risk factor for nephrolithiasis. We previously reported that Uromodulin (UMOD) protects against nephrolithiasis by upregulating the renal calcium channel TRPV5. This channel is crucial for calcium reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT). Recently, mutations in the gene encoding Mucin-1 (MUC1) were found to cause autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease, the same disease caused by UMOD mutations. Because of the similarities between UMOD and MUC1 regarding associated disease phenotype, protein structure, and function as a cellular barrier, we examined whether urinary MUC1 also enhances TRPV5 channel activity and protects against nephrolithiasis. We established a semiquantitative assay for detecting MUC1 in human urine and found that, compared with controls (n=12), patients (n=12) with hypercalciuric nephrolithiasis had significantly decreased levels of urinary MUC1. Immunofluorescence showed MUC1 in the thick ascending limb, DCT, and collecting duct. Applying whole–cell patch-clamp recording of HEK cells, we found that wild-type but not disease mutant MUC1 increased TRPV5 activity by impairing dynamin-2– and caveolin-1–mediated endocytosis of TRPV5. Coimmunoprecipitation confirmed a physical interaction between TRPV5 and MUC1. However, MUC1 did not increase the activity of N-glycan–deficient TRPV5. MUC1 is characterized by variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) that bind the lectin galectin-3; galectin-3 siRNA but not galectin-1 siRNA prevented MUC1-induced upregulation of TRPV5 activity. Additionally, MUC1 lacking VNTRs did not increase TRPV5 activity. Our results suggest that MUC1 forms a lattice with the N-glycan of TRPV5 via galectin-3, which impairs TRPV5 endocytosis and increases urinary calcium reabsorption.

Keywords: calcium, kidney stones, ion channel, hypercalciuria, endocytosis, electrophysiology

Nephrolithiasis is a common disorder with a lifetime risk of 10%–15%.1 Stone formation is caused by a sequence of events, including urinary supersaturation, crystal nucleation, growth, and finally, adhesion.2 Calcium is the most common constituent of kidney stones.3 Hypercalciuria is the most significant contributing risk factor for the development of nephrolithiasis, and it is detected in 35%–50% of patients with kidney stones.4 The determination of the final urinary calcium concentration occurs in the late distal convoluted tubule (DCT) and connecting tubule via transcellular reabsorption by the renal calcium channel TRPV5.5–7

Interestingly, the murine knockout of Uromodulin (Umod−/−), the most abundant protein in human urine, has hypercalciuria, renal calcium crystals, and calcifications.8 A genome–wide association study in humans showed a protective effect of a specific UMOD allele against calcium–containing kidney stones.9 UMOD decreases the risk of nephrolithiasis as a macromolecule with characteristics of inhibiting stone formation and by increasing the cell surface abundance of the renal calcium channel TRPV5.2,10 Mutations in UMOD result in autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease (ADTKD).11,12

Recently, Mucin-1 (MUC1) was described as another gene that results in ADTKD.12,13 There are >20 different human MUCs, which represent a family of large extracellular glycoproteins that are involved in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions.14–18 MUCs contribute to the formation of a mucus layer, protecting underlying mucosa in different organs.14,19,20 MUC1 contains an N-terminal subunit consisting of the signal peptide, a variable number tandem repeats (VNTR) domain, and a sea urchin sperm protein, enterokinase, and agrin domain.21,22 The MUC1-N subunit is tethered to the cell surface by noncovalent binding to the MUC1-C fragment, which contains short extracellular, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic domains.21 The hallmark of MUCs is the VNTR domain. In MUC1, each tandem repeat (TR) contains 20 amino acids.22 The MUC1 VNTR is heavily O-glycosylated and can range from 20 to 120 TRs, depending on the inherited maternal and paternal alleles. In the kidney, MUC1 is expressed in renal development and upregulated in renal cell carcinoma.23–26 Additionally, MUC1 protects against AKI.27 Otherwise, little is known about MUC1 in renal physiology.

There are several similarities between UMOD and MUC1. Both proteins are membrane proteins and have protein-protein interacting domains. UMOD is a GPI–anchored membrane protein, whereas MUC1 is a cell membrane–associated protein.16,28 Parts of UMOD and MUC1 are both secreted. Although UMOD is cleaved at the C terminus of the protein and becomes the most abundant protein in human urine, MUC1 undergoes autoproteolysis within the sea urchin sperm protein, enterokinase, and agrin domain, and MUC1-N is released.21,29 UMOD and MUC1 both form polymers, thus contributing to a viscous, protective layer at the epithelial surface.16,18,30,31 When mutated, both proteins are retained within cells, contribute to cellular apoptosis, and result in ADTKD.13,32 Because of these similarities between UMOD and MUC1, we examined the hypothesis that urinary MUC1 is decreased in calcium stone formers and that MUC1 may protect against kidney stones by enhancing TRPV5 channel activity.

Results

MUC1 Is Secreted in Human Urine and Decreased in Urine of Calcium Stone Formers

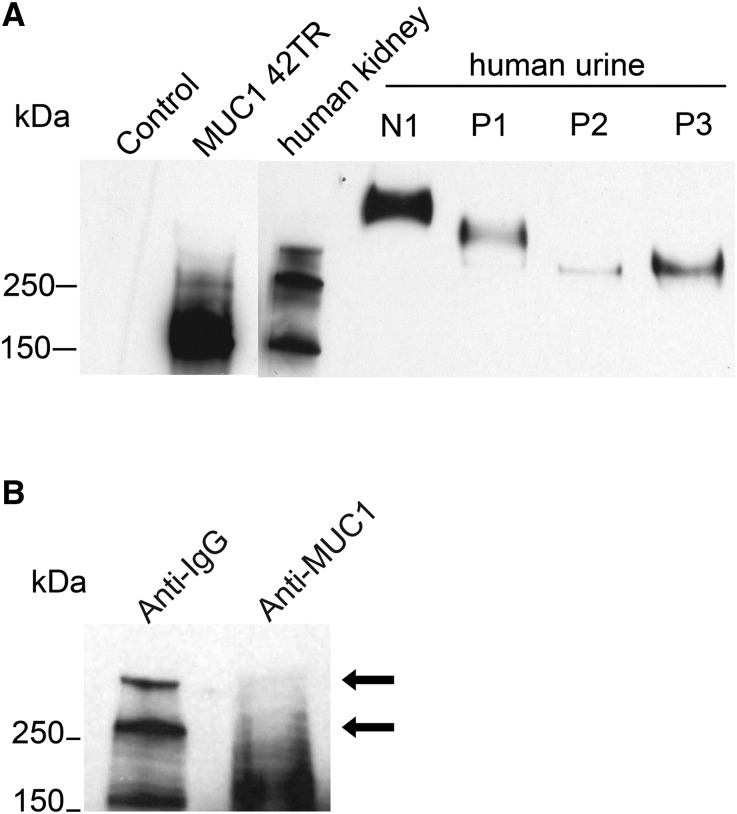

To study if urinary MUC1 concentration is decreased in patients who are hypercalciuric and calcium stone formers, we first tested different MUC1 ELISAs, which turned out to be unreliable. We, therefore, changed our approach for urinary MUC1 detection to a Western blot–based assay. Using a well published, monoclonal anti–MUC1 antibody (VU4H5),33–36 we detected a specific MUC1 band in cell lysate of human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells transfected with 42-TR MUC1 (Figure 1A). In human kidney lysate, we detected three different bands at approximately 170, 260, and 300 kD (Figure 1A). Immunodepletion experiments identified the 170-kD band as unspecific, thus indicating that the two larger bands are MUC1. Their differing sizes are most likely caused by different VNTRs in the maternally and paternally inherited MUC1 alleles (Figure 1B). Urine from a control subject (N1) and three individuals who were calcium stone formers (P1–P3) revealed higher molecular weight for MUC1 compared with cell or kidney lysate (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

MUC1 is expressed in human kidney and secreted in urine. (A) Compared with HEK293 cell lysate (control; lane 1), we identified a clear MUC1 band in cell lysate from HEK293 cells transfected with an MUC1 plasmid containing 42 TRs, yielding a protein size of approximately 200 kD by Western blot. In lysate from human kidneys, we detected three different bands at approximately 170, 260, and >300 kD. Shown is MUC1 expression in human urine from a healthy control (N1) and three patients with hypercalciuric nephrolithiasis (P1–P3). (B) Immunodepletion of human kidney lysate with MUC1 or control IgG shows the MUC1 antibody specificity (arrows).

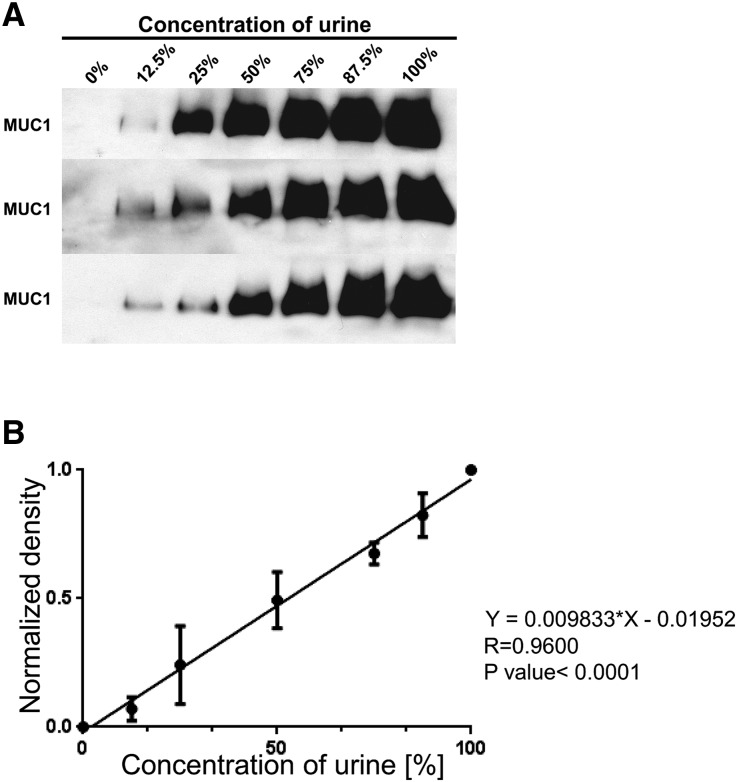

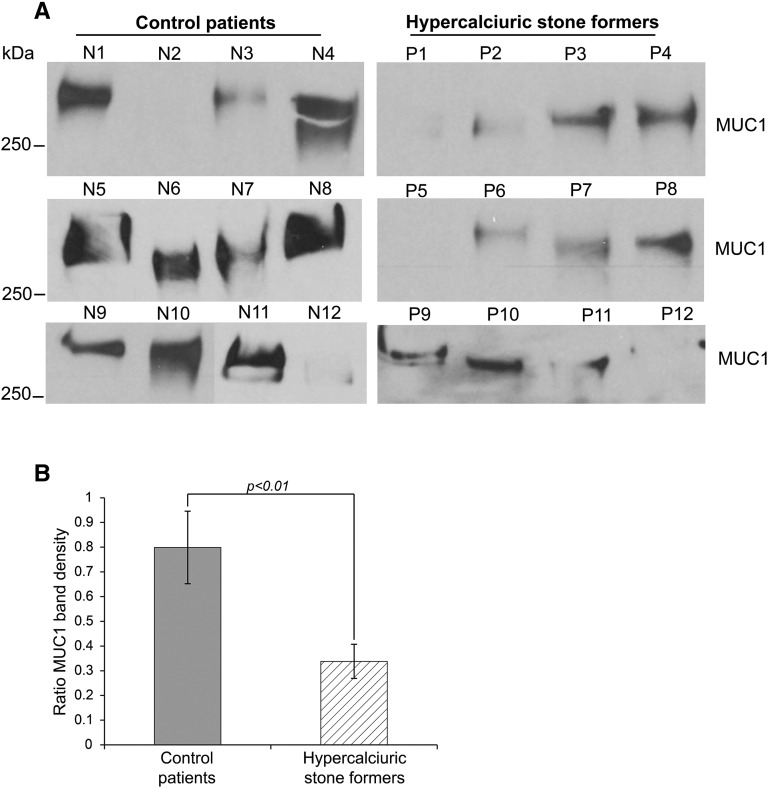

Serial dilutions of one individual’s urine done in triplicate showed that our Western blot–based assay detected urinary MUC1 within the linear dynamic range (Figure 2). To test if urinary MUC1 is decreased in hypercalciuric stone formers, we analyzed urine from calcium stone formers and control individuals semiquantitatively regarding MUC1. Clinical characteristics of both groups are shown in Table 1. There was less MUC1 in the urine of hypercalciuric stone formers compared with that in control individuals (P<0.01), supporting the notion that urinary MUC1 may protect against calcium nephrolithiasis (Figure 3). Despite some variability of urinary MUC1 molecular weight in controls and stone formers, there was no significant difference found between the two groups.

Figure 2.

Urinary MUC1 concentration can be analyzed semiquantitatively by Western blot. (A) Three separate MUC1 dilution experiments with increasingly less diluted urine from the same control individual resulted in comparable results regarding MUC1 band density. (B) A linear function between the urine concentration and the normalized MUC1 band density (diluted MUC1 band/100% MUC1 band density) was found in the three different dilution experiments.

Table 1.

Characteristics of individuals who were hypercalciuric and control individuals studied

| Control Patients | Patients Who Were Hypercalciuric | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 12 | 12 | NS |

| Age, yr | 48±14 | 58±21 | NS |

| Sex, women/men | 7/5 | 7/5 | NS |

| No. of stones | 0 | >12 | <0.01 |

| Urine | |||

| Ca2+, mg/d | 90±43 | 306±122 | <0.001 |

| pH | 6.3±0.4 | 6.2±0.5 | NS |

| Volume, ml | 1368±697 | 2155±752 | <0.05 |

| Na+, mEq/d | 159±125 | 164±76 | NS |

| K+, mEq/d | 56±31 | 73±36 | NS |

| Uric acid, mg/d | 418±172 | 701±442 | NS |

| Creatinine, mg/d | 1259±572 | 1453±775 | NS |

| Mg2+, mg/d | 83±47 | 130±30 | <0.05 |

| Cl−, mEq/d | 102±22 | 148±94 | NS |

| NH4+, mEq/d | 21±9 | 34±18 | NS |

| Citrate, mg/d | 598±389 | 746±334 | NS |

| Phosphorus, mg/d | 698±357 | 1111±527 | NS |

| Oxalate, mg/d | 27±18 | 38±11 | NS |

| SO42−, mmol/d | 15±8 | 23±13 | NS |

| Serum | |||

| BUN, mg/dl | 16±2 | 15±6 | NS |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.9±0.3 | 0.9±0.2 | NS |

| Calcium, mg/dl | 9.4±0.4 | 9.6±0.5 | NS |

| Phosphorus, mg/dl | 3.4±0.5 | 3.2±0.5 | NS |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 4.9±0.8 | 3.9±0.2 | NS |

| PTH, pmol/L | 70±23 | 44±18 | NS |

Ca2+, calcium; Na+, sodium; K+, potassium; Mg2+, magnesium; Cl−, chloride; NH4+, ammonium; SO42−, sulfate; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Figure 3.

Urinary MUC1 is significantly decreased in calcium stone formers versus controls. (A) The 24-hour urine samples from 12 controls and 12 hypercalciuric stone formers were compared semiquantitatively regarding urine MUC1 band density. (B) The urinary MUC1 band densities of control individuals and patients were analyzed. To compare multiple urine samples, even on different SDS gels, we determined an MUC1 band ratio by dividing the patient’s urinary MUC1 band density by the MUC1 band density of a urine sample used repeatedly as standard on every SDS gel. Significantly lower urine MUC1 band ratios were found in hypercalciuric stone formers (ratio of MUC1 band density: 0.8±0.15 for the control group versus 0.34±0.07 for stone formers; P<0.01).

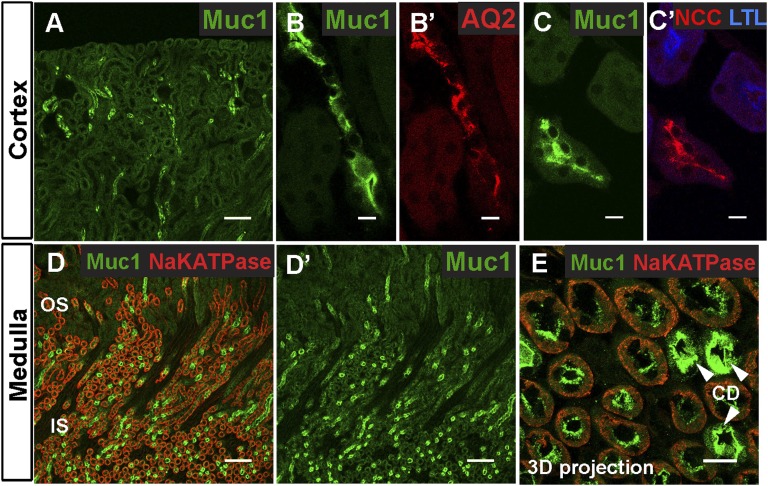

MUC1 Is Expressed in Different Tubular Segments

Human renal MUC1 expression analyzed in situ and by immunohistochemistry was previously published about DCT and collecting ducts (CDs), but a detailed assessment of its subcellular localization in vivo is not known.25,37 In patients with ADTKD and MUC1 mutations, MUC1 localizes to apical and intracellular regions in the thick ascending limb (TAL), DCT, and CD.13 We were interested in obtaining more detailed information about tubular expression of wild-type (WT) MUC1 by using immunofluorescence imaging and nephron-segment, specific markers (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Muc1 is expressed along different nephron segments in mouse kidney. (A, B, B′, C, and C′) Muc1 immunostaining in the renal cortex. A shows the tubules at low magnification. Muc1 (green) localizes to (B and B′) tubules with Aquaporin 2 (AQ2; red; a marker of the CDs) and (C and C′) tubules with NCC (red; a marker of DCTs) but not with L. tetragonolobus lectin (LTL; blue; a marker of proximal tubules). (D, D′, and E) Within the outer and inner stripes of the outer medulla, Muc1 (green) is highly expressed in CDs (arrowheads in E; AQ2 is not shown here). Higher magnification of a three-dimensional (3D) projection of a z stack reveals that low levels of Muc1 also localize to medullary tubules containing basolateral Na+/K+ ATPase (red), which depict TALs. Scale bars, 100 μm in A, D, and D′; 10 μm in B, B′, C, C′, and E.

Similar to UMOD, we detected MUC1 along apical membranes (Figure 4, A–C and E). Within the cortex, MUC1 localized to tubules expressing either Aquaporin 2 or NCC (Figure 4, A–C), confirming their localization to cortical DCT and CD.25 MUC1 did not colocalize with the proximal tubule marker Lotus tetragonolobus lectin, showing that MUC1 is not present in the proximal tubule in basal conditions (Figure 4, C and C′). In the medulla, MUC1 was expressed at high levels in medullary CDs (Figure 4, D and D′). Three-dimensional projection of a z stack of confocal images revealed that lower levels of MUC1 were found apically in tubules with basolateral Na+/K+ ATPase expression, which represent TAL tubules (Figure 4E). Importantly, the expression of MUC1 in the apical membranes of DCT is consistent with a possible role of MUC1 in regulation of TRPV5 channels, which are expressed at apical membranes in late DCT and the connecting tubule.38

MUC1 Upregulates TRPV5 Whole–Cell Current Density in a Dose-Dependent Fashion

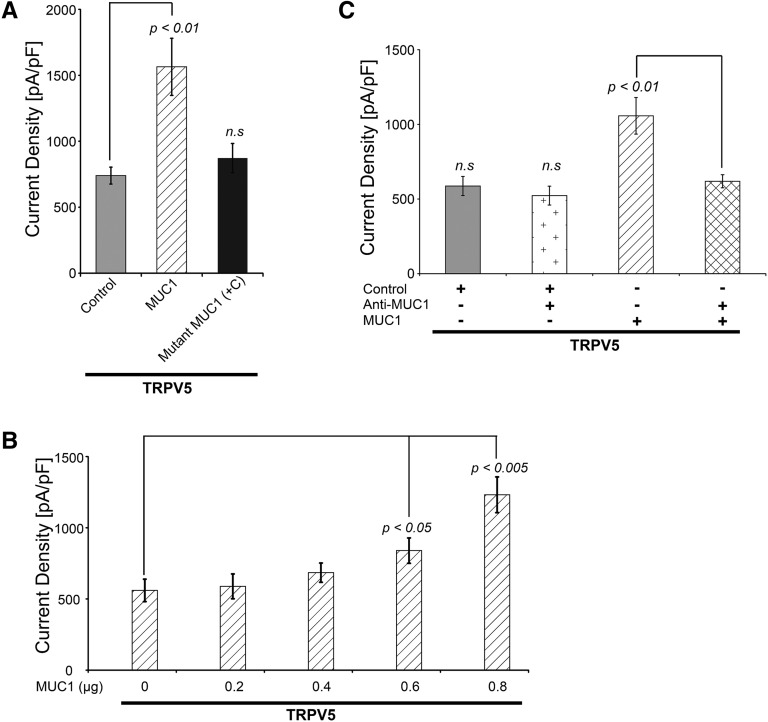

We tested our hypothesis that MUC1 regulates the renal calcium channel TRPV5 by analyzing TRPV5 whole-cell current density in HEK293 cells transfected with control, WT MUC1, or mutant MUC1 (c.428dupC, a frameshift mutation found in patients with ADTKD).13,39 Coexpression of TRPV5 and WT MUC1 increased TRPV5 current density by approximately 100% compared with control. Mutant MUC1 expression did not change TRPV5 current density compared with control (Figure 5A). The effect of MUC1 on TRPV5 channel current density was dose dependent (Figure 5B). Addition of anti-MUC1 antibody (targeting the VNTR) to the culture medium of cells cotransfected with TRPV5 and MUC1 blocked the effect of MUC1 to increase TRPV5 activity (Figure 5C). MUC1 did not alter TRPV5 stability or TRPV5 glycosylation patterns (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 5.

MUC1 increases TRPV5 whole–cell current density in a dose-dependent fashion. (A) In HEK293 cells, coexpression with WT MUC1 increased the TRPV5 current density (1565±217 pA/pF; P<0.01) compared with control (740±64 pA/pF) and ADTKD–causing frameshift mutant (+C) MUC1 (872±111 pA/pF; NS; n=5 for each group). (B) Cotransfection of increasing amounts of MUC1 plasmid resulted in increasingly higher TRPV5 current density (840±89 pA/pF with 0.6 μg MUC1 versus 560±79 pA/pF with 0 μg MUC1, P<0.05; n=5 for each group). (C) MUC1 antibody significantly decreased TRPV5 current density in TRPV5 and MUC1 cotransfected cells (1057±122 pA/pF for MUC1 versus 618±44 pA/pF for MUC1 and anti-MUC1; P<0.01). Anti-MUC1 alone had no effect on TRPV5 current density (587±64 pA/pF for control versus 523±66 pA/pF for control and anti-MUC1; NS; n=5 for each group).

MUC1 Is Expressed in a Wide Range of Cells and Physically Interacts with TRPV5

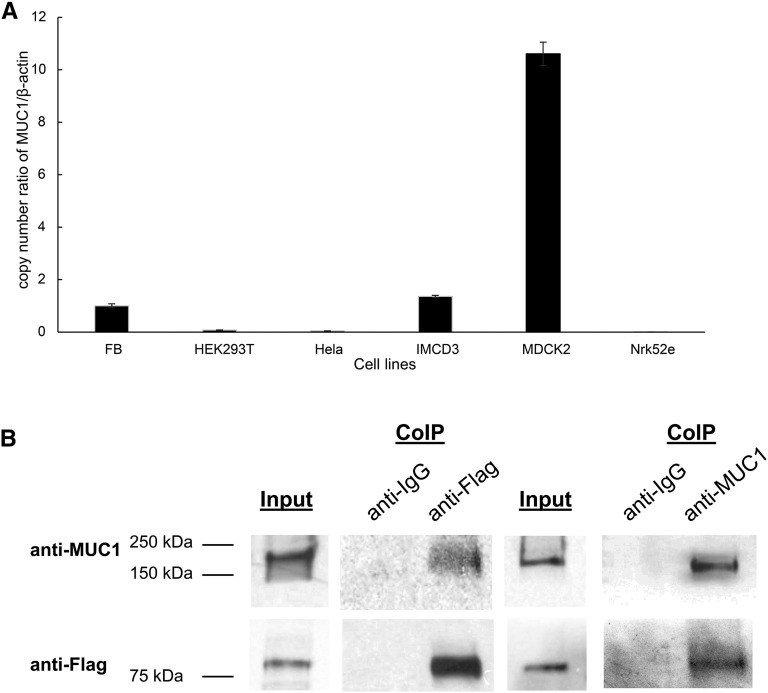

Because MUC1 is thought to be expressed on the apical surface of most secretory epithelia, we next examined how widely MUC1 is expressed.40 We performed real–time quantitative PCR of MUC1 in different cell lines ranging from fibroblasts to renal cells in different species (Figure 6A). We detected endogenous MUC1 in most analyzed cell lines from mouse (fibroblasts and IMCD3), rat (Nrk52e), dog (MDCK2), and humans (HEK293T and HeLa) in variable degrees. We then studied if MUC1 interacts physically with TRPV5. We performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments in HEK cells transfected with Flag-tagged TRPV5. Using anti-Flag to immunoprecipitate Flag-tagged TRPV5, we coimmunoprecipitated MUC1 (Figure 6B). Conversely, anti-MUC1 antibody was able to coimmunoprecipitate TRPV5 (Figure 6B). These experiments are consistent with a physical interaction between MUC1 and TRPV5.

Figure 6.

MUC1 is abundantly expressed and binds physically to TRPV5. (A) MUC1 mRNA is endogenously expressed in multiple cell lines. We identified MUC1 mRNA in a range of different cell lines from a variety of species using quantitative RT-PCR. Endogenous MUC1 was strongly detected in MDCK2, IMCD3, and fibroblast (FB) cells, and to a lower degree, also detected in HEK293T cells. A very small amount of MUC1 mRNA was found in HeLa and Nrk52e cells. (B) MUC1 binds TRPV5 channel. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with MUC1 and TRPV5-Flag. The antibody used for immunoprecipitation is shown above each panel (coimmunoprecipitation [CoIP]). Immunoprecipitated proteins were identified using Western blotting (WB) and specific antibodies as shown on the left. Cell lysate is shown at the left of each immunoprecipitation experiment. MUC1 is detected with precipitation of the MUC1-TRPV5 complex using anti-Flag antibody (lane 3), and TRPV5 is detected using anti-MUC1 antibody for precipitation (lane 6).

MUC1 Increases TRPV5 Activity by Impairing Dynamin-2– and Caveolin-1–Related Channel Endocytosis

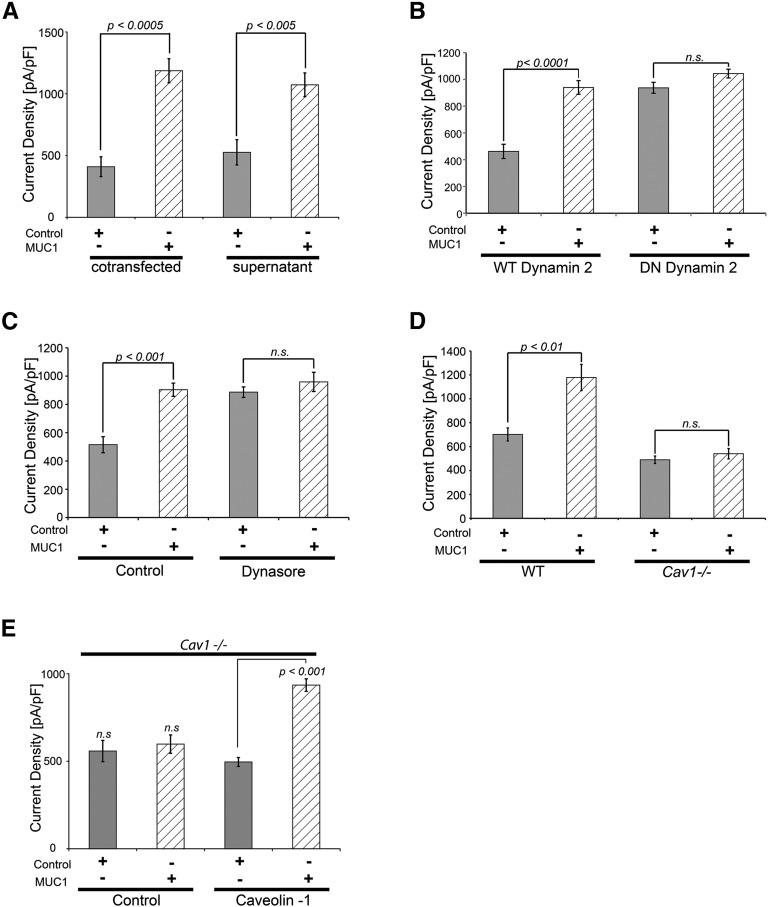

The identification of MUC1 in urine (Figures 1–3) and the ability of anti-MUC1 antibody added to culture medium to decrease MUC1–stimulated TRVP5 current density (Figure 5C) were consistent with an extracellular role of MUC1 in TRPV5 regulation. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that MUC1 increases TRPV5 channel activity from the extracellular side. Similar to MUC1 cotransfected cells, TRPV5-expressing cells exposed to MUC1-containing supernatant had an increase in TRPV5 current density (Figure 7A). We attempted an approximation to show that the MUC1 level used in supernatant is close to a physiologically relevant concentration. Applying the same conditions as for the experiment shown in Figure 7A, in a Western blot assay, MUC1-containing supernatant from overexpressing cells yielded a band density ranging between the band densities for urinary MUC1 from calcium stone formers and control individuals (Supplemental Figure 3). The urine volume loaded represents the urine output of approximately 1 second, thus emphasizing that control human urine contains a significant amount of MUC1. Previously published studies showed that extracellular regulation of TRPV5 involves dynamin– and caveolin (Cav) –related constitutive endocytosis of TRPV5.10,41–43 Therefore, we tested the role of dynamin-2 in MUC1 regulation of TRPV5. TRPV5 current density was upregulated by MUC1 when cotransfected with WT dynamin-2 (Figure 7B). Cells transfected with dominant negative dynamin-2, which impairs constitutive endocytosis, showed increased TRPV5 current density, even without MUC1 (Figure 7B). Stimulation with MUC1 did not result in any further increase of TRPV5 activity, suggesting that MUC1 increases TRPV5 by impairing dynamin-2–related endocytosis of TRPV5 (Figure 7B). This conclusion is further supported by experiments using dynasore, an inhibitor of dynamin GTPase activity and blocker of dynamin-dependent endocytosis44 (Figure 7C). To study the involvement of Cav1, which is also involved in TRPV5 endocytosis, we cotransfected Cav1−/− or WT fibroblasts with TRPV5 and control or MUC1. Upregulation of TRPV5 by MUC1 was abrogated in Cav1−/− cells but not in WT cells (Figure 7D). Higher current density was expected for TRPV5 in Cav1−/− cells, because TRPV5 endocytosis is impaired. We think that the unexpected lower current density in Cav1−/− cells may be because of a lower transfection efficiency in these cells. A similar pattern of lower TRPV5 current in Cav1−/− cells was seen in other publications as well.10,42 In Cav1−/− cells, overexpression of recombinant Cav1 but not control plasmid restored the upregulation of TRPV5 by MUC1, consistent with MUC1 increasing TRPV5 current density in a Cav1-dependent fashion (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

MUC1 upregulates TRPV5 from the extracellular space and impairs dynamin-2– and Cav1–dependent TRPV5 endocytosis. (A) MUC1 increases TRPV5 current density from the extracellular space. Cells cotransfected with MUC1 (410±80 pA/pF and control versus 1186±97 pA/pF and MUC1; P<0.0005) as well as TRPV5 transfected cells exposed to MUC1-containing supernatant show increased TRPV5 current density (526±102 pA/pF and control supernatant versus 1072±96 pA/pF and MUC1 supernatant; P<0.005), confirming extracellular upregulation of TRPV5 by MUC1. (B) MUC1 increases TRPV5 activity by impairing dynamin-2–dependent endocytosis of the channel. Whereas cells transfected with WT dynamin-2 showed the expected upregulation of TRPV5 current density with MUC1 (for WT dynamin-2: 462±53 pA/pF and control versus 940±51 pA/pF and MUC1; P<0.0001), cells transfected with dominant negative dynamin-2 displayed increased TRPV5 current density at baseline, indicating constitutive TRPV5 endocytosis by dynamin-2. In these cells, no additional increase of TRPV5 activity was noticed with MUC1 (for dominant negative dynamin-2: 937±41 pA/pF and control versus 1043±33 pA/pF and MUC1), indicating that TRPV5 upregulation by MUC1 occurs by impairing dynamin-2–dependent endocytosis. (C) Confirmation of MUC1 upregulation of TRPV5 by impairing dynamin–dependent TRPV5 endocytosis using dynasore. Using the dynamin GTPase inhibitor dynasore, which blocks dynamin-dependent endocytosis, we confirmed the lack of MUC1 effect on TRPV5 current density (no dynasore: 515±57 pA/pF and control versus 904±47 pA/pF and MUC1; P<0.001; plus dynasore: 887±37 pA/pF and control versus 959±68 pA/pF and MUC1; NS). (D) MUC1 increases TRPV5 activity by impairing Cav1-dependent endocytosis of the channel. Whereas WT fibroblasts showed the expected upregulation of TRPV5 current density with MUC1 (WT cells: 701±37 pA/pF and control versus 1178±109 pA/pF and MUC1; P<0.01), Cav1-deficient cells (Cav1−/−) displayed no further increase of TRPV5 activity when cotransfected with MUC1 (Cav1−/− cells: 490±31 pA/pF and control versus 541±43 pA/pF and MUC1; NS), indicating that TRPV5 upregulation by MUC1 occurs by impairing Cav1-dependent endocytosis. (E) TRPV5 upregulation by MUC1 in Cav1−/− cells is rescued by cotransfection of Cav1. Forced overexpression of Cav1 but not control plasmid restored the ability of TRPV5 upregulation by MUC1 (no Cav1: 558±61 pA/pF and control versus 598±53 pA/pF and MUC1; NS; with Cav1: 496±25 pA/pF and control versus 935±36 pA/pF and MUC1; P<0.001; n=5 for each group).

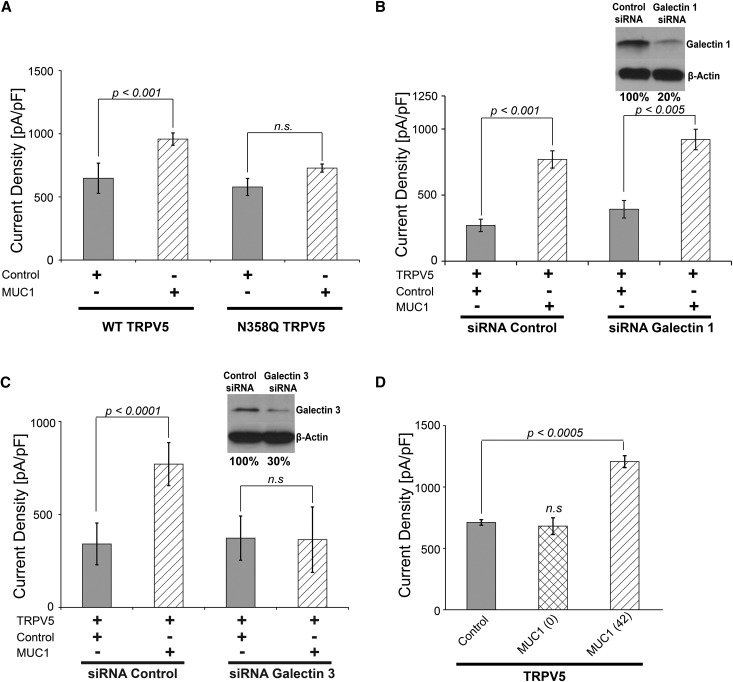

MUC1 Requires TRPV5 N-Glycan and Galectin-3 for Channel Upregulation

Because MUC1 modifies TRPV5 current density from the extracellular space and because the N-glycan of TRPV5 is required for TRPV5 upregulation by UMOD, we tested if MUC1 requires the N-glycan of TRPV5 for upregulation of current density.10 Analyzing the effect of MUC1 on WT- and N-glycan–deficient TRPV5 (TRPV5N358Q), we found that N-glycan–deficient TRPV5 was not stimulated by MUC1 in contrast to WT TRPV5 (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

MUC1 upregulation of TRPV5 requires the TRPV5 N-glycan and galectin-3. (A) The N-glycan of TRPV5 is required for upregulation by MUC1. WT TRPV5 responded to MUC1 cotransfection (WT TRPV5: 648±45 pA/pF and control versus 958±14 pA/pF and MUC1; P<0.001), whereas N-glycan–deficient (N358Q) TRPV5 did not react to MUC1 stimulation (N358Q TRPV5: 578±90 pA/pF and control versus 728±64 pA/pF and MUC1; NS). (B) Galectin-1 is not required for TRPV5 upregulation by MUC1. Knockdown of galectin-1 using siRNA did not impair the response of TRPV5 current density to MUC1 (control siRNA: 270±46 pA/pF and control versus 769±65 pA/pF and MUC1; P<0.001; galectin-1 siRNA: 393±65 pA/pF and control versus 920±77 pA/pF and MUC1; P<0.005). Using Western blotting, knockdown of galectin-1 is shown in the upper right panel. Quantification of the galectin-1 knockdown by densitometry shows a reduction of 80%. (C) Knockdown of galectin-3 abrogates upregulation of TRPV5 current density by MUC1 (control siRNA: 341±37 pA/pF and control versus 770±52 pA/pF and MUC1; P<0.0001; galectin-3 siRNA: 372±53 pA/pF and control versus 364±72 pA/pF and MUC1; NS). Using Western blotting, knockdown of galectin-3 is shown in the upper right panel. Quantification of the galectin-3 knockdown by densitometry shows a reduction of 70% (D) MUC1 lacking VNTR is not able to upregulate TRPV5 current density (711±23 pA/pF and control versus 681±68 pA/pF and zero-TR MUC1; NS) in contrast to MUC1 containing 42 TRs (1207±49 pA/pF and 42-TR MUC1; P<0.0005; n=5 for each group).

Galectins are an ancient, ubiquitous family of lectins characterized by an evolutionary conserved, approximately 130-amino acid-long carbohydrate recognition domain that binds β-galactosides.45,46 Galectins include 15 members. Galectin-1 is the family prototype, containing one carbohydrate recognition domain and forming homodimers. Galectin-1 binds to the TRPV5 N-glycan.42 Indeed, the antiaging hormone Klotho increases TRPV5 activity in a galectin-1–dependent manner.42 We examined the effect of reduced galectin-1 levels using galectin-1 siRNA. We found that knockdown of galectin-1 had no effect on the MUC1-mediated increase in TRPV5 activity, indicating that galectin-1 is not required for MUC1 upregulation of TRPV5 (Figure 8B).

Another possible candidate that emerged was galectin-3. Galectin-1 and -3 both comprise part of large crosslinked complexes that form lattice networks.42,47 Galectin-3 mediates the upregulation of TRPV5 cell surface abundance by Klotho.48 Galectin-3 is also known to bind N-glycans.49 Moreover, Galectin-3 binds MUC1 via O-glycans of the VNTR.20,49–51 Therefore, we investigated whether galectin-3 may be a critical mediator of TRPV5 upregulation by MUC1. We found that reduction of galectin-3 by using galectin-3 siRNA abrogated the increase in TRPV5 current density mediated by MUC1 (Figure 8C). This provides strong evidence that galectin-3 is an important mediator of TRPV5 stimulation by MUC1.

Because galectin-3 is known to bind O-glycans of the MUC1 VNTRs, we next studied the importance of the MUC1 VNTR domain for TRPV5 activity. We compared the effect of MUC1 with no repeats with that of MUC1 with 42 repeats on the TRPV5 channel activity. TRPV5 current density was increased by MUC1 containing 42 TRs but not by MUC1 with zero TRs (Figure 8D). This shows that the VNTR domain is critical for increasing TRPV5 current density by MUC1 and indirectly implicates galectin-3 binding to O-glycans of the MUC1 VNTR as a possible mechanism by which MUC1 and galectin-3 regulate TRPV5 activity.

Discussion

We show MUC1 as a novel urinary modifier of the renal calcium channel TRPV5, thus providing a physiologic function for MUC1 in the kidney. Using in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry, MUC1 expression was previously shown in the DCT and CD.25,37 Using immunofluorescence imaging, our data confirmed apical MUC1 expression in DCT and CD and low levels in TALs (Figure 4E). WT and mutant MUC1 were also shown in TALs by other groups.13,27

In our experiments, we show that MUC1 increases TRPV5 current density from the extracellular space. Upregulation of TRPV5 current density by MUC1 is consistent with MUC1 expression in the TAL and DCT and MUC1 secretion into the tubular lumen (Figures 1 and 4, C and E). Other previously published urinary proteins regulating TRPV5 include tissue kallikrein, Klotho, and UMOD.10,42,52 Tissue kallikrein activates the PLC/PKC signaling pathway by binding to bradykinin 2 receptor, and Klotho and UMOD enable lattice formation of TRPV5 and inhibit TRPV5 endocytosis.10,52,53 We show that the mechanism of MUC1-related upregulation of TRPV5 is similar but distinct from the molecular mechanisms described for Klotho and UMOD. All three proteins work from the extracellular space, impair TRPV5 endocytosis, and require the TRPV5 N-glycan for channel upregulation.10,42 For Klotho, a detailed molecular mechanism was deciphered in which Klotho functions as a specific α-2,6 sialidase, cleaving specific terminal sialic acids from the channel N-glycan. This allows galectin-1 to bind to the underlying disaccharide galactose-N-acetylglucosamine, thus enabling lattice formation and impairing channel endocytosis. In contrast, MUC1 requires galectin-3 for TRPV5 upregulation (Figure 8C). Consistent with our data, galectin-3 is expressed in murine DCT and urine.48 It was previously shown that galectin-3 increases TRPV5 calcium uptake in an N-glycan–dependent fashion.48 Klotho and sialidase treatment also increased TRPV5 calcium uptake, whereas adding galectin-3 to these respective conditions did not have any additional effect, implying that all three proteins activate TRPV5 in a similar fashion.48

We show that MUC1 interacts with TRPV5 and that galectin-3 is required for the upregulation of TRPV5 current by MUC1. Binding of galectin-3 via specific O-glycan modifications of the MUC1 VNTR region has been shown to be significant for progression of cancer and metastasis by causing MUC1 clustering on the cell surface.20,40,51,54–58 The galectin-3 to MUC1 interaction is also relevant in other organ systems. On the surface of the eye, galectin-3 and MUC1 colocalize, and physical interaction between cell surface–associated MUC1 and galectin-3 occurs in a galactose-dependent fashion.20 Additional proof for significance of the galectin-3 to MUC1 interaction under physiologic conditions was published for MDCK cells.50

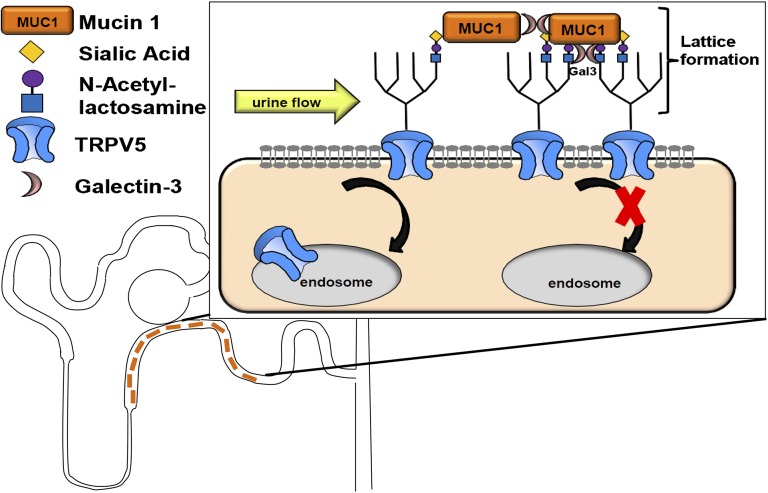

Our data are consistent with a role of MUC1 in preventing calcium–containing kidney stones (Figure 3). We propose a model, in which galectin-3 interacts with the TRPV5 N-glycan and the VNTR of MUC1 then binds to galectin-3, thus stabilizing the TRPV5 N-glycan to galectin-3 interaction (Figure 9). Alternatively, MUC1 could directly bind to TRPV5, and galectin-3 is needed for connecting multiple MUC1 molecules. In each case, galectin-3 enables lattice formation of TRPV5 channels and therefore, results in clustering of TRPV5 channels by impairing TRPV5 endocystosis (Figure 9). This results in increased apical channel cell surface abundance and increased urine calcium reabsorption, thus decreasing the risk of calcium-containing stones. In contrast to the mechanisms by which Klotho enhances TRPV5 channel activity, no additional sialidase activity was needed for the MUC1 effect on TRPV5 current density. We cannot rule out that endogenous neuraminidases, which carry sialidase activity, may be required for the MUC1 effect, because there are four different neuraminidases in humans that were also identified in human urine.59 Larger trials will be needed to confirm the usefulness of urinary MUC1 as a biomarker for increased risk of calcium nephrolithiasis. Our data show that MUC1 is a component of a urinary network of proteins that modify tubular channels, such as TRPV5.

Figure 9.

Model of TRPV5 channel upregulation by urinary MUC1. MUC1 is secreted in the ultrafiltrate along the TAL and the distal nephron. In the DCT and connecting tubule, urinary MUC1 binds to the N-glycan of TRPV5 (shown in the boxed area). Two different scenarios are possible. Either galectin-3 binds to the TRPV5 N-glycan, and MUC1 stabilizes the binding by binding galectin-3 via the O-glycans of the MUC1 VNTR, or MUC1 may bind directly to TRPV5 N-glycans, and galectin-3 is needed for aggregation of multiple MUC1 molecules via the O-glycans of the MUC1 VNTR. In both situations, galectin-3 enables lattice formation of TRPV5 because of MUC1, which impairs TRPV5 endocytosis and increases TRPV5 cell surface abundance (shown in the box).

Concise Methods

Materials and DNA Constructs

MUC1 plasmids containing zero and 42 TRs were obtained from O. J. Finn (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA). Mutant MUC1 plasmid was provided by B. Beck (University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany). Mutant MUC1 was constructed containing three VNTRs. The cytosine insertion was cloned into the second VNTR, thus resulting in formation of the neoprotein, including the third VNTR. WT MUC1 containing six TRs and mutant MUC1 containing the insertion of a cytosine were cloned into pCEP4. GFP-tagged TRPV5 contains the coding region of TRPV5 cloned in frame to commercial pEGFP-N3 vector.41 The well published mouse anti–MUC1 (VU4H5) antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-Flag antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The GFP–tagged TRPV5 WT and N358Q mutant constructs have been described in detail.42

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK293 cells were cultured as described previously.41 WT and Cav1−/− fibroblasts were cultured as reported earlier.10 Cells were transiently cotransfected with cDNA for WT or N-glycan–deficient (N358Q) GFP-TRPV5 plus cDNA for WT MUC1, mutant MUC1, MUC1 zero TRs, MUC1 42 TRs, WT dynamin-2, dominant negative (K44A) mutant of dynamin-2, or Cav1 as outlined elsewhere.10 When not otherwise mentioned, we used the MUC1 construct containing six TRs as the WT. If not otherwise documented, 1 μg MUC1 plasmid DNA was used for transfection. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. In each experiment, the total amount of plasmid DNA for transfection was balanced by empty vector. For galectin-1 and galectin-3 siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO), we transfected 40 and 20 nmol siRNA, respectively.

Electrophysiologic Recordings

Whole–cell patch-clamp pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (Dagan Corporation, Minneapolis, MN) and had resistance between 1.5 and 3 MΩ. Pipette and bath solutions were used as described earlier.10 Current densities were obtained by normalizing current amplitude (obtained at −150 mV) to cell capacitance. Whole-cell recordings were obtained with a low-pass filter set at 2 kHz using an eight–pole Bessel filter in the clamp amplifier. Data were sampled every 0.1 ms with a Digidata-1440A Interface.

Quantitative Real–Time PCR

Cell lysate was obtained from the following cells: fibroblasts (mouse), IMCD3 (mouse), MDCK2 (dog), Nrk52e (rat), HEK293 (human), and HeLa cells (human). Total RNA was extracted using the Quick-RNA MicroPrep Reagent (ZYMO Research, Irvine, CA), and 1 μg total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with random primers using the iScript Select cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Relative transcript expression levels were measured by quantitative real–time PCR using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Samples were run on the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). β-Actin was used for inner control. The following primer sequences were used: for cells from mouse: mMuc1-PF-ATGAGGAGGTTTCGGCAGGTAA and mMuc1-PR-GGGTGGGGTGACTTGCTCCT (expected size =101 bp), mACTB-qPF-TAAAACCCGGCGGCGCA and mACTB-qPR-CATTCCCACCATCACACCCTGG (expected size =248 bp); for cells from rat: rMuc1-PF-TCCAAGTCAGCAGCCCATCTC and rMuc1-PR-AAGGAGACCCCGACAGACAAC (expected size 141 bp); rACTB-qPF- CCACCCGCGAGTACAACCTTC and rACTB-qPR- CATCCATGGCGAACTGGTGGC (expected size =72 bp); for cells from dog: dMuc1-PF-TCCCAGCAGCAACTACTACCA and dMuc1-PR-GCATCAGTGGCACCATTTCGG (expected size =162 bp); dACTB-qPF-TCTTGGGTGTTGGGGAGAAGG and dACTB-qPR- AGGCCAGTACCCATAATTCCCC (expected size =142 bp); and for human cell lines: hMUC1-PF-CTGCCAACTTGTAGGGGCAC and hMUC1-PR- CCGAGAAATTGGTGGGGCCT (expected size =170 bp); hACTB-qPF- GAGCACAGAGCCTCGCCTTT and hACTB-qPR-TCATCCATGGTGAGCTGGCG (expected size =67 bp).

Glycosylation Analyses

HEK293 cells were transfected with TRPV5 and control or TRPV5 and MUC1. Cell pellets were harvested, and lysates were treated by Endoglycosidase H and N-Glycosidase F (PNGase F) following the manufacturer’s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Ten micrograms each protein sample was denatured at 65°C for 10 minutes; 10× reaction buffer (10% NP-40 needed to be added for the PNGase F reaction) and 1000 U Endoglycosidase H, PNGase F, or equal volume of water (in the control reaction) were added to the 40-μl reaction and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Then, 2× Laemmli sample buffer was added into each reaction. Samples were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Protein Stability Analyses

HEK293 cells were transfected with TRPV5 and control or TRPV5 and MUC1. Cells were harvested at 24, 48, and 72 hours. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer; 2× Laemmli sample buffer was added to each sample. Samples were denatured at 65°C for 10 minutes. Equal amounts of protein samples were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Coimmunoprecipitation, Immunoblotting, and Immunodepletion

HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 42-TR MUC1 and Flag-tagged TRPV5 using Lipofectamine 2000 and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C. Cells were collected and lysed using a needle syringe. The protein concentration in the cell lysate was determined using protein assay (DC Protein Assay; Bio-Rad). Samples were adjusted to the same concentration with buffer. Samples were resolved on a 4%–20% gradient gel and processed for immunblotting using specific antibodies. For experiments, we used 700 μg cell lysate for coimmunoprecipitation, using 3 μg anti-Flag or anti-MUC1 antibodies overnight. Species–specific anti–IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as control. Antigen-antibody complex was then loaded onto Protein G Beads (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) by slow rotation overnight. The antibody-loaded beads were then washed. Sample buffer was added, and proteins were denatured at 65°C for 10 minutes. Samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. For immunodepletion, human kidney lysate was incubated with either anti-IgG or anti-MUC1 for 5 hours. Antigen-antibody complexes were pulled down with Protein G Beads. The same volume of MUC1-depleted supernatant was then visualized on an SDS gel with immunoblotting.

Urine Collection of Control Patients and Patients Who Were Hypercalciuric and Had Kidney Stones

In collaboration with the Charles and Jane Pak Center for Mineral Metabolism and Clinical Research, we obtained samples from 24-hour urine collections. Urine was collected from 12 patients who were hypercalciuric and had kidney stones and 12 control patients. Patients who were hypercalciuric were selected among those without established diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism, distal renal tubular acidosis, chronic diarrheal conditions, and repeated urinary tract infections. None of the patients received treatment with thiazide diuretic, thiazide analogs, alkali treatment, or allopurinol. Informed consent was obtained in adherence to the project–specific institutional review board (STU 022014–055; University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center). Because of widely differing urine volume (Table 1), urine specimen was corrected for total creatinine. Urine was denatured at 65°C for 15 minutes and loaded on an SDS gel with 4× sample buffer. To obtain a comparable number, an individual ratio for each resulting MUC1 band was determined by dividing the MUC1 band density by a standardized sample. The resulting ratios were compared for control and hypercalciuric stone formers. Age, sex, and degree of hypercalciuria were reviewed and are distributed as shown in Table 1.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Male WT mice were fed a regular diet and euthanized at the age of 3 months. Anesthetized mice were perfused with paraformaldehyde, and the kidneys were harvested and embedded in paraffin. Sections were deparaffinized, and antigen retrieval was performed (Trilogy; Cell Marque). Sections were blocked with 10% donkey sera in PBS, and immunofluorescence was performed with Muc1 antibody (1:50; Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) overnight at 4°C. Fluorescence images were obtained using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 Microscope (Carl Zeiss GmbH, Jena, Germany) with a Zeiss AxioCam MRc Camera (Carl Zeiss GmbH) or a Zeiss LSM510 Confocal Microscope (Carl Zeiss GmbH). All animal experiments were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines and approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. O. J. Finn for sharing Mucin-1 plasmids containing 0 and 42 tandem repeats. We are grateful to Beverley Huet for support with statistical analysis. We are thankful to Paulette Padalino and John Poindexter for support regarding clinical data on patients with stones. We highly appreciate the scientific input from Drs. M. Baum, V. Patel, and A. Rodan.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health grants R01DK009478 (to D.K.M.) and K08DK95994-04 (to M.T.F.W.), the March of Dimes Basil O’Connor (to D.K.M.), the Carl W. Gottschalk Research Scholar Grant from the American Society of Nephrology (to M.T.F.W.), and the Children’s Clinical Research Advisory Committee, Children’s Health System (Dallas, TX; to M.T.F.W.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015101100/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sakhaee K, Maalouf NM, Kumar R, Pasch A, Moe OW: Nephrolithiasis-associated bone disease: Pathogenesis and treatment options. Kidney Int 79: 393–403, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar V, Lieske JC: Protein regulation of intrarenal crystallization. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 15: 374–380, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moe OW, Pearle MS, Sakhaee K: Pharmacotherapy of urolithiasis: Evidence from clinical trials. Kidney Int 79: 385–392, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frick KK, Bushinsky DA: Molecular mechanisms of primary hypercalciuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1082–1095, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costanzo LS, Windhager EE, Ellison DH: Calcium and sodium transport by the distal convoluted tubule of the rat. 1978. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1562–1580, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoenderop JG, van Leeuwen JP, van der Eerden BC, Kersten FF, van der Kemp AW, Mérillat AM, Waarsing JH, Rossier BC, Vallon V, Hummler E, Bindels RJ: Renal Ca2+ wasting, hyperabsorption, and reduced bone thickness in mice lacking TRPV5. J Clin Invest 112: 1906–1914, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Topala CN, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG: Regulation of the epithelial calcium channel TRPV5 by extracellular factors. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 16: 319–324, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Mo L, Goldfarb DS, Evan AP, Liang F, Khan SR, Lieske JC, Wu XR: Progressive renal papillary calcification and ureteral stone formation in mice deficient for Tamm-Horsfall protein. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F469–F478, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gudbjartsson DF, Holm H, Indridason OS, Thorleifsson G, Edvardsson V, Sulem P, de Vegt F, d’Ancona FC, den Heijer M, Wetzels JF, Franzson L, Rafnar T, Kristjansson K, Bjornsdottir US, Eyjolfsson GI, Kiemeney LA, Kong A, Palsson R, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K: Association of variants at UMOD with chronic kidney disease and kidney stones-role of age and comorbid diseases. PLoS Genet 6: e1001039, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf MT, Wu XR, Huang CL: Uromodulin upregulates TRPV5 by impairing caveolin-mediated endocytosis. Kidney Int 84: 130–137, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hart TC, Gorry MC, Hart PS, Woodard AS, Shihabi Z, Sandhu J, Shirts B, Xu L, Zhu H, Barmada MM, Bleyer AJ: Mutations of the UMOD gene are responsible for medullary cystic kidney disease 2 and familial juvenile hyperuricaemic nephropathy. J Med Genet 39: 882–892, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckardt KU, Alper SL, Antignac C, Bleyer AJ, Chauveau D, Dahan K, Deltas C, Hosking A, Kmoch S, Rampoldi L, Wiesener M, Wolf MT, Devuyst O: Autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease: Diagnosis, classification, and management--A KDIGO consensus report. Kidney Int 88: 676–683, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirby A, Gnirke A, Jaffe DB, Barešová V, Pochet N, Blumenstiel B, Ye C, Aird D, Stevens C, Robinson JT, Cabili MN, Gat-Viks I, Kelliher E, Daza R, DeFelice M, Hůlková H, Sovová J, Vylet’al P, Antignac C, Guttman M, Handsaker RE, Perrin D, Steelman S, Sigurdsson S, Scheinman SJ, Sougnez C, Cibulskis K, Parkin M, Green T, Rossin E, Zody MC, Xavier RJ, Pollak MR, Alper SL, Lindblad-Toh K, Gabriel S, Hart PS, Regev A, Nusbaum C, Kmoch S, Bleyer AJ, Lander ES, Daly MJ: Mutations causing medullary cystic kidney disease type 1 lie in a large VNTR in MUC1 missed by massively parallel sequencing. Nat Genet 45: 299–303, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Etzold S, Juge N: Structural insights into bacterial recognition of intestinal mucins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 28: 23–31, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corfield AP: Mucins: A biologically relevant glycan barrier in mucosal protection. Biochim Biophys Acta 1850: 236–252, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollingsworth MA, Swanson BJ: Mucins in cancer: Protection and control of the cell surface. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 45–60, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonckheere N, Skrypek N, Frénois F, Van Seuningen I: Membrane-bound mucin modular domains: From structure to function. Biochimie 95: 1077–1086, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hattrup CL, Gendler SJ: Structure and function of the cell surface (tethered) mucins. Annu Rev Physiol 70: 431–457, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roy MG, Livraghi-Butrico A, Fletcher AA, McElwee MM, Evans SE, Boerner RM, Alexander SN, Bellinghausen LK, Song AS, Petrova YM, Tuvim MJ, Adachi R, Romo I, Bordt AS, Bowden MG, Sisson JH, Woodruff PG, Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, De la Garza MM, Moghaddam SJ, Karmouty-Quintana H, Blackburn MR, Drouin SM, Davis CW, Terrell KA, Grubb BR, O’Neal WK, Flores SC, Cota-Gomez A, Lozupone CA, Donnelly JM, Watson AM, Hennessy CE, Keith RC, Yang IV, Barthel L, Henson PM, Janssen WJ, Schwartz DA, Boucher RC, Dickey BF, Evans CM: Muc5b is required for airway defence. Nature 505: 412–416, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Argüeso P, Guzman-Aranguez A, Mantelli F, Cao Z, Ricciuto J, Panjwani N: Association of cell surface mucins with galectin-3 contributes to the ocular surface epithelial barrier. J Biol Chem 284: 23037–23045, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macao B, Johansson DG, Hansson GC, Härd T: Autoproteolysis coupled to protein folding in the SEA domain of the membrane-bound MUC1 mucin. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 71–76, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanisch FG, Müller S: MUC1: The polymorphic appearance of a human mucin. Glycobiology 10: 439–449, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fanni D, Iacovidou N, Locci A, Gerosa C, Nemolato S, Van Eyken P, Monga G, Mellou S, Faa G, Fanos V: MUC1 marks collecting tubules, renal vesicles, comma- and S-shaped bodies in human developing kidney tubules, renal vesicles, comma- and s-shaped bodies in human kidney. Eur J Histochem 56: e40, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraus S, Abel PD, Nachtmann C, Linsenmann HJ, Weidner W, Stamp GW, Chaudhary KS, Mitchell SE, Franke FE, Lalani N: MUC1 mucin and trefoil factor 1 protein expression in renal cell carcinoma: Correlation with prognosis. Hum Pathol 33: 60–67, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leroy X, Copin MC, Devisme L, Buisine MP, Aubert JP, Gosselin B, Porchet N: Expression of human mucin genes in normal kidney and renal cell carcinoma. Histopathology 40: 450–457, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leroy X, Zerimech F, Zini L, Copin MC, Buisine MP, Gosselin B, Aubert JP, Porchet N: MUC1 expression is correlated with nuclear grade and tumor progression in pT1 renal clear cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 118: 47–51, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pastor-Soler NM, Sutton TA, Mang HE, Kinlough CL, Gendler SJ, Madsen CS, Bastacky SI, Ho J, Al-Bataineh MM, Hallows KR, Singh S, Monga SP, Kobayashi H, Haase VH, Hughey RP: Muc1 is protective during kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F1452–F1462, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rampoldi L, Scolari F, Amoroso A, Ghiggeri G, Devuyst O: The rediscovery of uromodulin (Tamm-Horsfall protein): From tubulointerstitial nephropathy to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 80: 338–347, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santambrogio S, Cattaneo A, Bernascone I, Schwend T, Jovine L, Bachi A, Rampoldi L: Urinary uromodulin carries an intact ZP domain generated by a conserved C-terminal proteolytic cleavage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 370: 410–413, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kufe DW: Mucins in cancer: Function, prognosis and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 874–885, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaeffer C, Santambrogio S, Perucca S, Casari G, Rampoldi L: Analysis of uromodulin polymerization provides new insights into the mechanisms regulating ZP domain-mediated protein assembly. Mol Biol Cell 20: 589–599, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rampoldi L, Caridi G, Santon D, Boaretto F, Bernascone I, Lamorte G, Tardanico R, Dagnino M, Colussi G, Scolari F, Ghiggeri GM, Amoroso A, Casari G: Allelism of MCKD, FJHN and GCKD caused by impairment of uromodulin export dynamics. Hum Mol Genet 12: 3369–3384, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cascio S, Zhang L, Finn OJ: MUC1 protein expression in tumor cells regulates transcription of proinflammatory cytokines by forming a complex with nuclear factor-κB p65 and binding to cytokine promoters: Importance of extracellular domain. J Biol Chem 286: 42248–42256, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki Y, Sutoh M, Hatakeyama S, Mori K, Yamamoto H, Koie T, Saitoh H, Yamaya K, Funyu T, Habuchi T, Arai Y, Fukuda M, Ohyama C, Tsuboi S: MUC1 carrying core 2 O-glycans functions as a molecular shield against NK cell attack, promoting bladder tumor metastasis. Int J Oncol 40: 1831–1838, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung SE, Seo KY, Kim H, Kim HL, Chung IH, Kim EK: Expression of MUC1 on corneal endothelium of human. Cornea 21: 691–695, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engelstaedter V, Heublein S, Schumacher AL, Lenhard M, Engelstaedter H, Andergassen U, Guenthner-Biller M, Kuhn C, Rack B, Kupka M, Mayr D, Jeschke U: Mucin-1 and its relation to grade, stage and survival in ovarian carcinoma patients. BMC Cancer 12: 600, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao Y, Karsten U, Zerban H, Bannasch P: Expression of MUC1, Thomsen-Friedenreich-related antigens, and cytokeratin 19 in human renal cell carcinomas and tubular clear cell lesions. Virchows Arch 436: 119–126, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoenderop JG, Müller D, Van Der Kemp AW, Hartog A, Suzuki M, Ishibashi K, Imai M, Sweep F, Willems PH, Van Os CH, Bindels RJ: Calcitriol controls the epithelial calcium channel in kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1342–1349, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ekici AB, Hackenbeck T, Morinière V, Pannes A, Buettner M, Uebe S, Janka R, Wiesener A, Hermann I, Grupp S, Hornberger M, Huber TB, Isbel N, Mangos G, McGinn S, Soreth-Rieke D, Beck BB, Uder M, Amann K, Antignac C, Reis A, Eckardt KU, Wiesener MS: Renal fibrosis is the common feature of autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney diseases caused by mutations in mucin 1 or uromodulin. Kidney Int 86: 589–599, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Q, Guo X, Nash GB, Stone PC, Hilkens J, Rhodes JM, Yu LG: Circulating galectin-3 promotes metastasis by modifying MUC1 localization on cancer cell surface. Cancer Res 69: 6799–6806, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cha SK, Wu T, Huang CL: Protein kinase C inhibits caveolae-mediated endocytosis of TRPV5. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1212–F1221, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cha SK, Ortega B, Kurosu H, Rosenblatt KP, Kuro-O M, Huang CL: Removal of sialic acid involving Klotho causes cell-surface retention of TRPV5 channel via binding to galectin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 9805–9810, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conner SD, Schmid SL: Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature 422: 37–44, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirchhausen T, Macia E, Pelish HE: Use of dynasore, the small molecule inhibitor of dynamin, in the regulation of endocytosis. Methods Enzymol 438: 77–93, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elola MT, Wolfenstein-Todel C, Troncoso MF, Vasta GR, Rabinovich GA: Galectins: Matricellular glycan-binding proteins linking cell adhesion, migration, and survival. Cell Mol Life Sci 64: 1679–1700, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haudek KC, Patterson RJ, Wang JL: SR proteins and galectins: What’s in a name? Glycobiology 20: 1199–1207, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demetriou M, Granovsky M, Quaggin S, Dennis JW: Negative regulation of T-cell activation and autoimmunity by Mgat5 N-glycosylation. Nature 409: 733–739, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leunissen EH, Nair AV, Büll C, Lefeber DJ, van Delft FL, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG: The epithelial calcium channel TRPV5 is regulated differentially by klotho and sialidase. J Biol Chem 288: 29238–29246, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.More SK, Srinivasan N, Budnar S, Bane SM, Upadhya A, Thorat RA, Ingle AD, Chiplunkar SV, Kalraiya RD: N-glycans and metastasis in galectin-3 transgenic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 460: 302–307, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poland PA, Rondanino C, Kinlough CL, Heimburg-Molinaro J, Arthur CM, Stowell SR, Smith DF, Hughey RP: Identification and characterization of endogenous galectins expressed in Madin Darby canine kidney cells. J Biol Chem 286: 6780–6790, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu LG, Andrews N, Zhao Q, McKean D, Williams JF, Connor LJ, Gerasimenko OV, Hilkens J, Hirabayashi J, Kasai K, Rhodes JM: Galectin-3 interaction with Thomsen-Friedenreich disaccharide on cancer-associated MUC1 causes increased cancer cell endothelial adhesion. J Biol Chem 282: 773–781, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Picard N, Van Abel M, Campone C, Seiler M, Bloch-Faure M, Hoenderop JG, Loffing J, Meneton P, Bindels RJ, Paillard M, Alhenc-Gelas F, Houillier P: Tissue kallikrein-deficient mice display a defect in renal tubular calcium absorption. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3602–3610, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang Q, Hoefs S, van der Kemp AW, Topala CN, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG: The beta-glucuronidase klotho hydrolyzes and activates the TRPV5 channel. Science 310: 490–493, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hilkens J, Ligtenberg MJ, Vos HL, Litvinov SV: Cell membrane-associated mucins and their adhesion-modulating property. Trends Biochem Sci 17: 359–363, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu LG: The oncofetal Thomsen-Friedenreich carbohydrate antigen in cancer progression. Glycoconj J 24: 411–420, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bresalier RS, Niv Y, Byrd JC, Duh QY, Toribara NW, Rockwell RW, Dahiya R, Kim YS: Mucin production by human colonic carcinoma cells correlates with their metastatic potential in animal models of colon cancer metastasis. J Clin Invest 87: 1037–1045, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakamori S, Ota DM, Cleary KR, Shirotani K, Irimura T: MUC1 mucin expression as a marker of progression and metastasis of human colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology 106: 353–361, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu FT, Rabinovich GA: Galectins as modulators of tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer 5: 29–41, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roozbeh J, Merat A, Bodagkhan F, Afshariani R, Yarmohammadi H: Significance of serum and urine neuraminidase activity and serum and urine level of sialic acid in diabetic nephropathy. Int Urol Nephrol 43: 1143–1148, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.