Abstract

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype influences onset age of Alzheimer’s disease but effects on disease progression are less clear. We investigated amyloid-β (Aβ) levels and change in relationship to APOE genotype, using two different measures of Aβ in two different longitudinal cohorts. Aβ accumulation was measured using PET imaging and 11C-Pittsburgh compound-B (PiB) in 113 Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) participants (mean age 77.3 years; 107 normal, 6 cognitively impaired) and CSF Aβ1–42 assays in 207 BIOCARD study participants (mean age 62 years; 195 normal,12 cognitively impaired). Participants in both cohorts had up to 7 serial assessments (mean 2.3–2.4). PET-PiB retention increased and CSF Aβ1–42 declined longitudinally. APOE ε4 was significantly associated with higher PET-PiB retention and lower CSF Aβ1–42, independent of age and sex, but APOE genotype did not significantly affect Aβ change over time. APOE ε4 carriers may be further along in the disease process, consistent with earlier brain Aβ deposition and providing a biological basis for APOE genotype effects on onset age of Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: PET amyloid imaging, CSF Aβ1–42, biomarkers, Apolipoprotein E genotype, longitudinal

1. Introduction

Epidemiologic studies have shown that the Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 risk allele is associated with a lower age of onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in a dose-dependent manner, such that two ε4 alleles are associated with the earliest onset age.[1] However, studies of the effect of APOE ε4 genotype on rate of disease progression have shown inconsistent associations.[2–4]

One method to elucidate the mechanism by which APOE genotype affects disease progression is to study the relationship between APOE genotype and amyloid-beta (Aβ) accumulation. Recent studies have confirmed that Aβ pathology, indexing AD-associated plaques, likely begins more than ten to fifteen years before the diagnosis of clinical dementia.[5] The development of tools for in vivo evaluation of Aβ biomarkers allows measurement of disease state and progression, including preclinical staging of AD in cognitively normal individuals.[6] These tools permit investigation of Aβ deposition over time, as well as associations between Aβ burden and APOE genotype. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging studies of Aβ consistently demonstrate increases over time in individuals with more than minimal Aβ at baseline imaging, where “more than minimal” refers to a threshold for detection of elevated Aβ.[7–9] Although a number of studies have demonstrated an association between the APOE ε4 risk allele and Aβ burden on imaging, even in non-demented individuals,[9–12] the relatively brief history of PET radiotracers for in vivo Aβ imaging has limited the availability of longitudinal measurements for investigation of rates of change.[13] Similarly, lower levels of CSF Aβ have been associated with increased risk of progression from MCI to AD.[14] However, longitudinal studies of CSF Aβ in cognitively normal individuals at risk of progression are limited, primarily due to the long follow-up times that are required.[15] APOE ε4 carriers have lower CSF levels of Aβ[16,17] but few studies have characterized the longitudinal trajectories of CSF Aβ in relation to APOE genotype.

We investigated longitudinal changes in biomarkers of Aβ deposition and their associations with APOE genotype using data from two prospective cohorts. Using data from the neuroimaging substudy of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA), we used PET and 11C Pittsburgh compound-B (PET-PiB) to investigate longitudinal changes in Aβ deposition and the relation of baseline Aβ levels and Aβ changes with APOE genotype in 113 older adults. Using complementary data from the BIOCARD study, we investigated serial changes in CSF Aβ1–42 for 207 participants in BIOCARD, and the relation of CSF Aβ1–42 to APOE genotype. In both cohorts, participants were evaluated at 1 to 2 year intervals and had up to 7 serial Aβ assessments. We first confirm prior observations that PET-PiB retention increases over time, especially in individuals with more than minimal Aβ burden at baseline,[7] and show significant decreases in CSF Aβ1–42 over time. Next, we show that APOE genotype affects level of Aβ, with higher PET-PiB retention and lower CSF Aβ with age in ε4 carriers compared with non-carriers. However, APOE genotype does not significantly influence rates of Aβ change over time, measured by PET-PiB or CSF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Research protocols were approved by the local institutional review boards, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.1.1. BLSA

The sample included 113 participants (63 men, 50 women) from the neuroimaging substudy of the BLSA. The BLSA neuroimaging substudy was initiated in 1994 and included annual magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of brain structure and PET scans of regional cerebral blood flow through 2003.[18] At enrollment, participants were free of central nervous system disease (dementia, stroke, bipolar illness, epilepsy), severe cardiac disease (myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease requiring angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery), severe pulmonary disease, or metastatic cancer. Since 2003, participants older than 80 years have continued to receive annual assessments, while those between the ages of 60 and 79 years are assessed every 2 years, and those whose age is less than age 60 years are assessed every 4 years. Beginning in 2005, participants received amyloid PET scans. At baseline PET-PiB, 3 of the 113 participants were no longer normal and had a consensus diagnosis[19,20] of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), two had diagnoses of AD, and one was Impaired-Not MCI. Diagnoses of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) were based on DSM-III-R[21] and the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria[22], respectively. Mean (SD) age at baseline 11C-PiB imaging was 77.3 (8.1); participants were studied at 1 to 2- year intervals with up to 7 (mean 2.3 SD 1.6) scans over up to 8 years since 2005. The sample overlaps those reported previously.[7,11] Characteristics of the present sample are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS

| BLSA | BIOCARD ≥55 | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 113 | 207 |

|

Age at Baseline mean (SD) |

77.3 (8.1) | 62 (6.4) |

| range | 56 to 93 | 55 to 86 |

| Female, No. (%) | 50 (44%) | 116 (56.0%) |

| White, No. (%) | 92 (81%) | 202 (97.6%) |

|

Education (yrs) mean (SD) |

16.8 (2.1) | 17.2 (2.3) |

| Range | 12 to 20 | 12 to 20 |

|

No. Assessments mean (SD) |

2.3 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.5) |

| Range | 1 to 7 | 1 to 7 |

| N with 1 | 51 | 78 |

| N with 2 | 21 | 44 |

| N with 3 | 20 | 38 |

| N with 4 or more | 21 | 47 |

|

Follow-up interval (yrs from baseline) mean (SD) |

2.2 (2.4) | 2.4 (2.6) |

| Range | 0 to 7 | 0 to 9.1 |

| APOE, No. (%) | ||

| e4− | 76 (67%) | 126 (61%) |

| e4+ | 33 (29%) | 81 (39%) |

| Missing | 4 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| MMSE at baseline | 28.7 (1.7) | 29.5 (0.8) |

| Diagnosis at baseline | ||

| Normal | 107 | 195 |

| MCI | 3 | 4 |

| Impaired, Not MCI | 1 | 7 |

| Dementia | 2 | 1 |

2.1.2. BIOCARD

The BIOCARD Study enrolled and followed a cohort of 349 cognitively normal individuals who were primarily in middle age. By design the majority had a first-degree relative with AD (approximately 75%). Neuropsychological assessments were conducted annually and MRI scans and CSF and blood specimens were obtained approximately every 2 years. The study was initiated at the NIH in 1995, and was stopped in 2005 for administrative reasons. In 2009, investigators at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine were funded to reestablish the cohort, continue the annual clinical and cognitive assessments, collect blood, and evaluate the previously acquired MRI scans and CSF and blood specimens.[15]

At baseline, all participants completed a comprehensive evaluation at the Clinical Center of the NIH. This evaluation consisted of a physical and neurologic examination, an ECG, standard laboratory studies, and neuropsychological testing. Individuals were excluded from participation if they were cognitively impaired, as determined by cognitive testing, or had significant medical, psychiatric, or neurologic disorders. Since the study has been conducted at Johns Hopkins, the clinical evaluation has included the following: a physical and neurologic examination, assessments of medication use, behavioral and mood assessments, family history of dementia, history of symptom onset, and a Clinical Dementia Rating, based on a semi-structured interview.[23,24] The clinical assessments given at the NIH covered similar domains. Consensus diagnosis of cognitive status was based on clinical data, reports of changes in cognition by the subject and by collateral sources, and decline in cognitive performance on objective tests. Clinical diagnoses were made blinded to the results of CSF analyses.

To increase comparability with the BLSA sample, the BIOCARD data included in the current analysis was restricted to CSF samples collected at age 55 years and older (N = 207), yielding a mean age (SD) of 62 (6.4) with up to 7 serial assessments (mean 2.4, SD 1.5). Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

2.2. PET Imaging and Image Processing

Dynamic 11C-PiB PET studies were performed in 3D mode on a GE Advance scanner. Participants were fitted with a thermoplastic head-mask to minimize motion during scanning. The PET scanning started immediately after IV bolus injection of a mean (SD) 14.7 (0.8) mCi of 11C-PiB. PET data were acquired according to the following protocol for the duration of the frames: 4×0.25, 8×0.5, 9×1, 2×3, and 10×5 min (70 min total, 33 frames). Dynamic images were reconstructed using filtered back-projection with a ramp filter (image size = 128 × 128, pixel size = 2 × 2 mm, slice thickness = 4.25 mm), yielding a spatial resolution of approximately 4.5 mm FWHM at the center of the field of view.

The Statistical Parametric Mapping PET template was affinely registered onto the 20-minute mean PET-PiB image for each PET scan study separately, and the resulting transformations were used to map the AAL atlas labels[25] accordingly on each PET-PiB distribution volume ratio (DVR) image. Quantification of DVR was performed using the AAL cerebellar gray matter reference regions that have been mapped to the native space of each PET image and a simplified reference tissue model.[26] Mean cortical DVR (cDVR) was calculated as the average of DVR values in superior, middle and inferior frontal and orbitofrontal, superior parietal, supramarginal and angular gyrus regions, precuneus, superior, middle and inferior occipital, superior, middle and inferior temporal, anterior, middle and posterior cingulate regions.

A two-class Gaussian mixture model was fitted to baseline mean cDVR data. The cDVR value corresponding to the intersection of the probability density functions of the two classes was used to define the separation between minimal and higher than minimal levels of PiB retention.

2.3. CSF measurement

Detailed procedures for acquisition and measurement of CSF Aβ1–42 are described in Moghekar et al.[15] Briefly, CSF was collected from 307 participants at baseline. Of these, 199 had CSF collected on more than one visit during the time the study was conducted at the NIH. The CSF specimens were analyzed using the same protocol used in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. This protocolvused the xMAP-based AlzBio3 kit (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) run on the Bioplex 200 system. The kit contains monoclonal antibodies specific for Ab1–42 (4D7A3), total tau (t-tau) (AT120), and p-tau181p (AT270), each chemically bonded to unique sets of color-coded beads, and analyte-specific detector antibodies (HT7, 3D6). Calibration curves were produced for each biomarker using aqueous buffered solutions that contained the combination of 3 biomarkers at concentrations ranging from 25 to 1,555 pg/mL for recombinant tau, 54 to 1,799 pg/mL for synthetic Ab1–42, and 15 to 258 pg/mL for a synthetic tau peptide phosphorylated at the threonine 181 position (i.e., the p-tau181p standard). All assays were run in triplicate. Each subject had all their samples analyzed on the same plate, and the same batch of plates (same lot number) was used for analyzing CSF from the whole cohort. An external high volume CSF Standard was used across all plates to ensure Aβ values were within +/− 5% of previously determined mean concentration.

2.4. APOE Genotype

APOE genotype in both cohorts was determined by standard procedures.[27] APOE ε4 carrier status was coded by creating an indicator variable, with APOE ε4 carriers coded as 1, if they had at least one ε4 allele, and non-carriers coded as 0.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Linear mixed models were used in all analyses (SAS 9.3, Cary, NC). To estimate annual rates of change, mean cDVR or CSF Aβ1–42 were used as the dependent variables and follow-up time from baseline in years (interval) as the main predictor. Other covariates included were: baseline age (defined as age at initial PET-PiB or first CSF Aβ1–42 from age 55), sex, and their interactions with time interval. Random effects were intercept and coefficient of interval, and unstructured covariance structure was assumed for random effects. To investigate the effects of APOE genotype on baseline levels and change in Aβ, we added genotype (APOE ε4 carrier vs. non-carrier) and its interactions with baseline age and interval to the model. Baseline age was mean centered, sex was coded as −0.5 as female and 0.5 as male. BLSA participants missing APOE genotype data were not included in analyses of the effects of APOE on Aβ.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Baseline Age and Longitudinal Change in Aβ

3.1.1. PET-PiB Imaging in BLSA

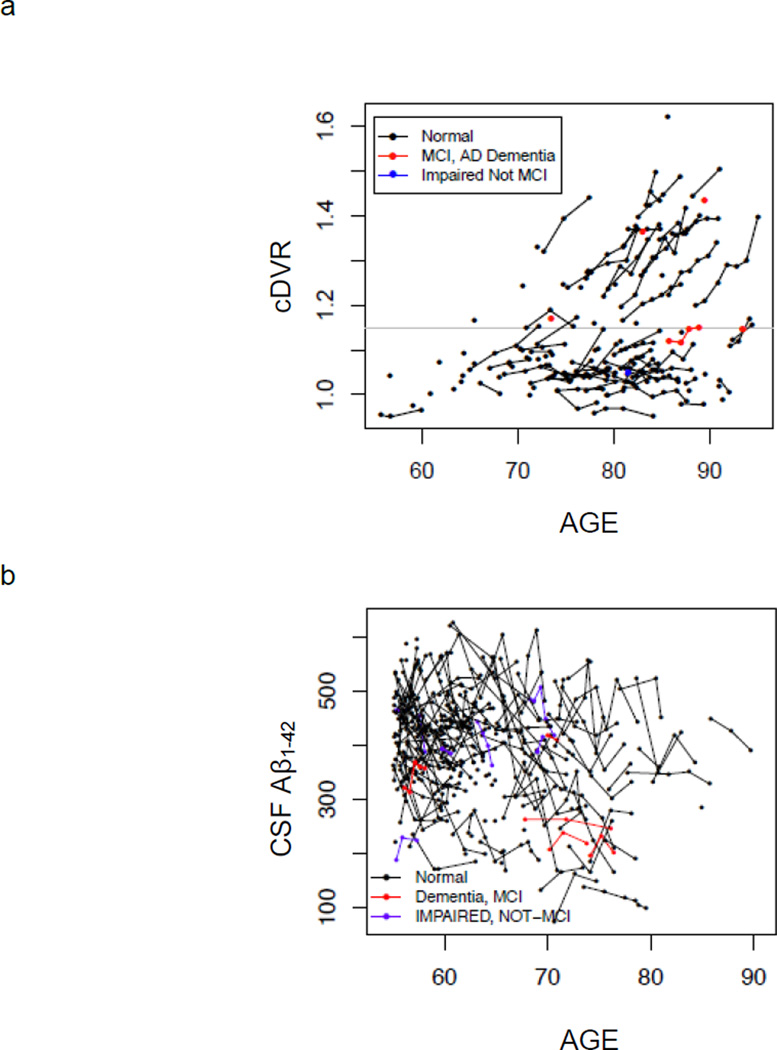

PET-PiB cDVR showed significant cross-sectional elevations with advancing age (p = 0.002). Longitudinal findings revealed overall increases in PET-PiB cDVR over time in the whole sample, after adjusting for baseline age and sex, of 0.86% per year (p<0.0001). Individuals with more than minimal PET-PiB retention at baseline (cDVR of 1.15 or greater based on a two-class Gaussian mixture model) showed increases over time of approximately 2% per year (p<0.0001). In contrast, individuals with minimal PiB retention at baseline (cDVR less than 1.15) tended to remain stable over time (0.40% per year). Longitudinal trajectories of amyloid deposition are shown for the entire sample in Figure 1a. Notably, with the longer follow-up intervals in the present report compared with our earlier observations,[7] we now observe the beginning of an upward trajectory in some of the oldest-old individuals with initially low baseline PiB retention (see Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Observed values of Aβ over time for (a) PET-PiB mean cortical DVR (cDVR) and (b) CSF Aβ1–42. Within-individual changes are shown by connecting lines. Individuals who are cognitively normal at baseline evaluation are shown in black, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer disease in red, and “cognitively impaired, not MCI” in blue. Threshold for detection of elevated PiB retention is shown as a gray line in (a).

3.1.2. CSF Aβ in BIOCARD

Similar results were obtained from linear mixed effects regression of serial CSF Aβ1–42 levels in the BIOCARD sample (Figure 1b). Overall rates of CSF declines over time were -5.51 pg/ml per year (p = 0.005). BIOCARD CSF data were not analyzed as a function of baseline CSF Aβ1–42 because Gaussian mixture models did not yield a clear cutpoint for grouping.

3.2. APOE genotype as a modifier of Aβ

3.2.1. APOE Genotype and PET-PiB Aβ

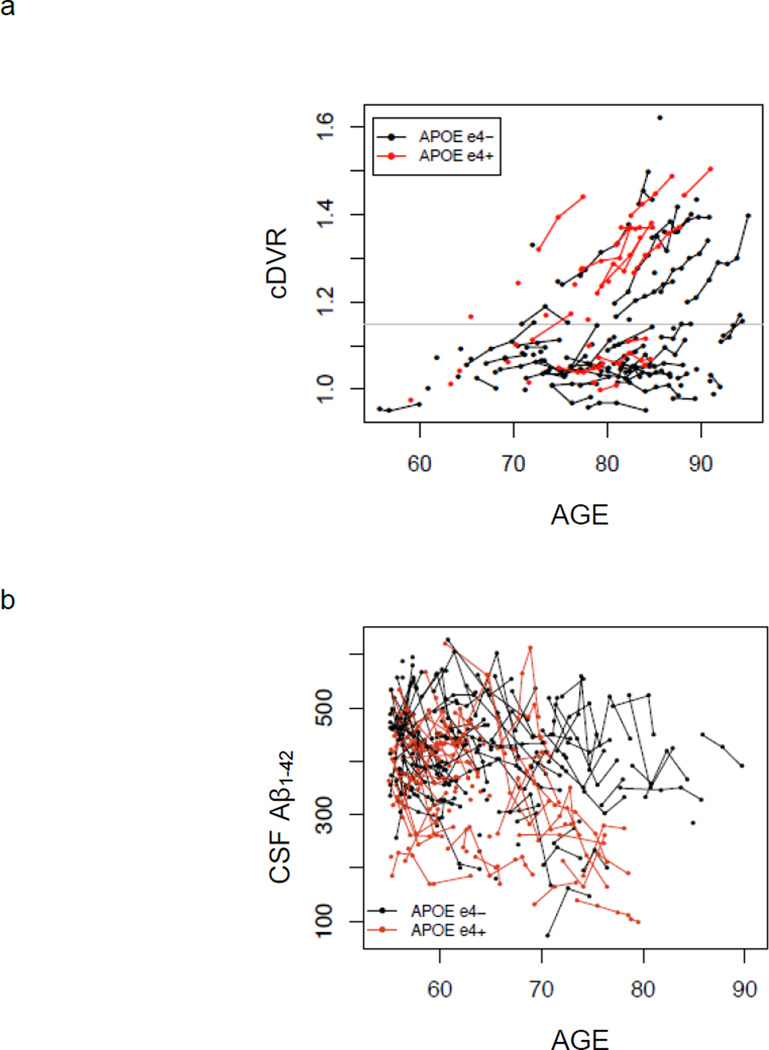

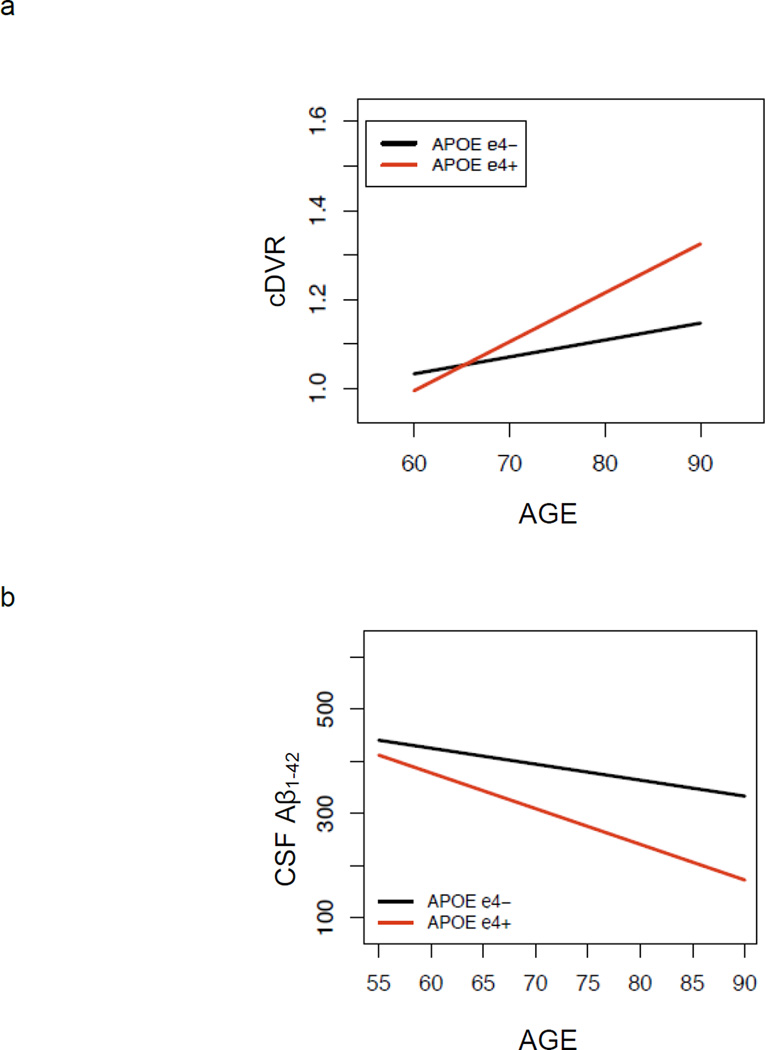

Mixed model results investigating effects of APOE genotype on level of Aβ burden at baseline PET-PiB imaging and change in Aβ over time are shown in Table 2, and individual trajectories over time as a function of APOE ε4 carrier status are shown in Figure 2a. APOE ε4 carriers compared with non-carriers had significantly higher Aβ burden overall (p = 0.001). There was a significant age by APOE genotype interaction (p <0.05), indicating greater Aβ elevations with age for ε4 carriers compared with non-carriers (Figure 3a). However, the effect of APOE genotype on rate of increase in PiB retention over time did not reach significance (p = 0.12). Rates of change in Aβ deposition were similar for men and women, and the trend toward greater rates of Aβ increase in older individuals did not reach significance (p = 0.082). Separate analyses of three individual regions of interest, precuneus, lateral temporal and inferior frontal regions, showed significant effects of APOE genotype on levels of Aβ (p < 0.002) but not on rates of change in Aβ (p > 0.05). Sensitivity analyses excluding non-white individuals, as well as data points subsequent to diagnosis of AD or MCI, yielded similar findings. Additional sensitivity analysis adding education as a covariate showed no significant main effect of education or significant interactions between APOE genotype and education on Aβ.

Table 2.

Mixed Model Results Examining Effects of APOE Genotype on Aβ Biomarkers

| BLSA | BIOCARD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Estimate | Standard Error |

Pr > |t| | Estimate | Standard Error |

Pr > |t| |

| Intercept | 1.125 | 0.011 | <.0001 | 418.99 | 8.55 | <0.0001 |

| Sex | 0.04 | 0.023 | 0.088 | −12.76 | 13.46 | 0.344 |

| Age | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.0002 | −3.06 | 1.20 | 0.012 |

| APOE ε4 genotype | 0.082 | 0.025 | 0.001 | −54.84 | 13.72 | 0.0001 |

| Age * APOE ε4 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.047 | −3.77 | 2.11 | 0.076 |

| Interval | 0.009 | 0.001 | <0.0001 | −5.51 | 1.90 | 0.005 |

| Age* interval | 0.0004 | 0.0002 | 0.082 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.550 |

| Sex*interval | 0.0009 | 0.003 | 0.754 | 2.34 | 2.90 | 0.423 |

| APOE ε4*interval | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.120 | −2.72 | 2.92 | 0.355 |

Significant results are in bold.

Figure 2.

Observed values of Aβ over time stratified by APOE ε4 carrier status for (a) PET-PiB mean cortical DVR (cDVR) and (b) CSF Aβ1–42. Within-individual changes are shown by connecting lines. APOE ε4 negative individuals are shown in black and APOE ε4 positive in red. Threshold for detection of elevated PiB retention is shown as a gray line in (a).

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional effect of age on (a) PET-PiB mean cortical DVR (cDVR) and (b) CSF Aβ1–42, showing stronger association of age with Aβ for APOE ε4 carriers compared with non-carriers. This interaction reached significance for PET-PiB (p = 0.047) and was at trend level for CSF Aβ1–42 (p = 0.076).

3.2.2. APOE genotype and CSF Aβ1–42

Analogous results were observed in analyses investigating the effect of APOE genotype on overall level of CSF Aβ, as well as change over time, in the BIOCARD sample (Table 2, Figure 2b and 3b). APOE ε4 carriers had significantly lower overall levels of CSF Aβ compared with non-carriers (p = 0.0001). There was a trend toward an age by APOE interaction (p = 0.076), indicating a greater reduction in CSF Aβ with age in APOE ε4 carriers compared with non-carriers. Consistent with the BLSA PET-PiB assessment of Aβ burden, the effect of APOE genotype on rate of change in CSF Aβ did not reach significance (p = 0.355). Sensitivity analysis restricted to individuals who remained free of cognitive impairment showed similar results, with the age by APOE interaction reaching significance in the restricted sample (p = 0.01). Sensitivity analyses adding education and its interaction with APOE showed no significant effects of these terms on Aβ.

4. Discussion

We investigated longitudinal rates of change in two biomarkers of Aβ and associations of APOE genotype with overall levels and changes over time in these biomarkers. Our samples included a large number of participants and up to 7 serial assessments, with 3 or more measurements in more than one-third of the samples. Analysis of PET-PiB measures of Aβ in BLSA and CSF Aβ1–42 in BIOCARD yielded remarkably similar findings despite the use of different biomarkers and two distinct longitudinal cohorts. Our results demonstrated significant increases in PET-PiB retention and declines in CSF Aβ1–42 over time. Further, we confirmed previously reported associations between APOE genotype and Aβ levels,[5,11,12,28] with APOE ε4 carriers showing higher PET-PiB retention and lower CSF Aβ1–42 compared with non-carriers. We extended these findings by demonstrating an interaction between age and APOE genotype that indicated more pronounced associations of Aβ with age in APOE ε4 carriers than non-carriers, in part driven by greater likelihood of elevated Aβ with age in APOE e4 carriers. In contrast to the effects of APOE genotype on Aβ biomarker levels, APOE genotype did not significantly modify rates of change in Aβ over time. Together, these findings suggest that APOE ε4 carriers are further along in the disease process, but that effects of APOE genotype on disease progression are less pronounced.

In this expanded sample and extended longitudinal follow-up of BLSA participants, we confirm and extend our initial observation[7] that PET-PiB imaging of in vivo amyloid burden is sensitive to even small increases in Aβ deposition over time. We found an overall increase in PET-PiB cDVR of 0.86% per year. Similarly, we found complementary longitudinal decreases in CSF Aβ1–42 of 5.51 pg/ml per year in BIOCARD, a distinct longitudinal cohort with a younger mean age. Further, in the PET-PiB BLSA cohort, we investigated whether baseline PET-PiB retention was associated with longitudinal increases in Aβ. Consistent with our initial report in a smaller sample[7] and findings from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle study[29], longitudinal increases in PiB retention were most pronounced in individuals with more than minimal baseline Aβ, approaching 2% per year in our subgroup of Aβ accumulators. In addition, Figure 1 shows that the initial stages of amyloid accumulation are detectable with longitudinal follow-up, even in some older individuals with low baseline PET-PiB retention. Thus, amyloid deposition can be initiated at very old ages despite stable levels in the preceding years, confirming that a negative Aβ scan at old ages does not guarantee prolonged absence of neuropathology. The distribution of CSF1–42 values and the younger ages of the BIOCARD cohort did not allow similar analysis of association with baseline level of Aβ and observations at older ages, but the data presented in Figure 1b suggest that CSF measures of Aβ may begin changing and plateau earlier than those associated with PET-PiB. Prospective studies using both biomarkers in the same sample are necessary to test this hypothesis.

Our second goal was to confirm the reported effect of APOE genotype on Aβ burden and to investigate potential effects of APOE genotype on rates of increase in Aβ. Although a prior PET-PiB study suggested that APOE ε4 carriers showed higher rates of Aβ deposition, this finding did not hold after age adjustment.[9] Our results confirm the association between APOE ε4 carrier status and higher Aβ burden for both PET-PiB and CSF measures, but neither biomarker of Aβ burden showed significant effects of APOE genotype on change in Aβ over time.

While epidemiological studies indicate that APOE ε4 carriers compared with non-carriers have earlier onset age of AD in a dose-dependent manner,[1] the mechanisms explaining this observation are not clear. Our findings confirm cross-sectional observations[11,12] that Aβ levels are higher in APOE ε4 carriers vs. non-carriers at any given age during the preclinical phase, consistent with a younger onset of brain Aβ deposition and a later disease stage in APOE ε4 carriers compared with non-carriers. Combined with similar rates of Aβ progression in ε4 carriers and non-carriers for both PET-PiB and CSF Aβ and the lag between initiation of Aβ deposition and appearance of clinical symptoms,[5] the earlier initiation of Aβ deposition may explain, in part, the earlier age of AD onset in APOE ε4 carriers. These findings may provide a biological substrate for the shift in the age of onset distribution of AD observed in epidemiological studies and may explain the less consistent associations of APOE genotype with disease progression. This interpretation is supported by recent findings from the BIOCARD study[30] showing that baseline scores on 9 cognitive tests and APOE ε4 status were independently associated with time to onset of clinical symptoms, whereas APOE ε4 status was associated with rates of cognitive change in only 2 measures.

Our study has several strengths including the use of two different biomarkers of Aβ burden in two distinct well-characterized longitudinal cohorts. Limitations of our study include the relatively high level of education which characterizes both cohorts and may limit generalizability to individuals with lower educational levels. In addition, there were only a limited number of individuals homozygous for the APOE ε4 allele, and we were unable to investigate ε4 dose effects. Further, the relatively recent development of amyloid imaging and the gap in obtaining additional CSF samples in BIOCARD resulted in limited follow-up intervals to date in these ongoing studies. It is possible that with additional follow-up and larger samples, APOE ε4 carriers may show significantly higher rates of change in Aβ than non-carriers, but the current data suggest that the magnitude of any potential effect on rate of change in Aβ is less than the effect on overall level of Aβ burden.

5. Conclusion

Overall, our results in two longitudinal cohorts show that PET and CSF biomarkers of brain amyloid burden reliably detect even modest levels of Aβ and change in Aβ deposition even in asymptomatic individuals. Moreover, APOE genotype modulates level but does not significantly affect change in Aβ though it is possible that more subtle effects of the ε4 risk allele on within-individual rates of Aβ deposition will be evident in larger samples with longer follow-up intervals. In conclusion, the ability to track Aβ deposition over time with both PET imaging and CSF biomarkers provides tools for investigation of the evolution of AD neuropathology in relation to onset of clinical symptoms and to guide patient selection and therapeutic monitoring in clinical trials.

APOE genotype effects on Aβ were assessed in 2 cohorts with different Aβ markers.

PET-PiB and CSF Aβ showed significant longitudinal increases in Aβ burden.

APOE ε4 AD risk allele was associated with increased level but not change in Aβ.

APOE ε4 carriers may be further along in the disease process.

This provides one explanation for APOE effects on AD onset age.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Prince owns Diagnosoft, Inc. stock, which is subject to certain restrictions under University policy. Dr. Prince also is a paid consultant to Diagnosoft, Inc.

The BLSA study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging and by Research and Development Contract HHSN-260-2004-00012C. We are grateful to the BLSA participants and staff for their dedication to these studies and the staff of the Johns Hopkins PET facility for their assistance. We are especially grateful to Wendy Elkins and Brieana Viscomi for their assistance with coordination and data collection for the PET-PiB studies.

The BIOCARD study is supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health: U01-AG03365, P50- AG005146 and P41-RR015241. The BIOCARD Study consists of 7 Cores with the following members: (1) the Administrative Core (Marilyn Albert, Barbara Rodzon, Richard Power), (2) the Clinical Core (Ola Selnes, Marilyn Albert, Rebecca Gottesman, Ned Sacktor, Guy McKhann, Scott Turner, Leonie Farrington, Maura Grega, Daniel D’Agostino, Sydney Feagen, David Dolan, Hillary Dolan), (3) the Imaging Core (Michael Miller, Susumu Mori, Tilak Ratnanather, Timothy Brown, Hayan Chi, Anthony Kolasny, Kenichi Oishi, Thomas Reigel, William Schneider, Laurent Younes), (4) the Biospecimen Core (Richard O’Brien, Abhay Moghekar, Richard Meehan), (5) the Informatics Core (Roberta Scherer, Curt Meinert, David Shade, Ann Ervin, Jennifer Jones, Matt Toepfner, Lauren Parlett, April Patterson, Lisa Lassiter), the (6) Biostatistics Core (Mei-Cheng Wang, Yi Lu, Qing Cai), and (7) the Neuropathology Core (Juan Troncoso, Barbara Crain, Olga Pletnikova, Gay Rudow, Karen Fisher).

We are grateful to the members of the BIOCARD Scientific Advisory Board who provide continued oversight and guidance regarding the conduct of the study including: Drs. John Csernansky, David Holtzman, David Knopman, Walter Kukull and John McArdle, as well as Drs. Neil Buckholtz, John Hsiao, Laurie Ryan and Jovier Evans, who provide oversight on behalf of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), respectively. We would also like to thank the members of the BIOCARD Resource Allocation Committee who provide ongoing guidance regarding the use of the biospecimens collected as part of the study, including: Drs. Constantine Lyketsos, Carlos Pardo, Gerard Schellenberg, Leslie Shaw, Madhav Thambisetty, and John Trojanowski.

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Geriatric Psychiatry Branch (GPB) of the intramural program of the NIMH who initiated the study (PI: Dr. Trey Sunderland). We are particularly indebted to Dr. Karen Putnam, who has provided ongoing documentation of the GPB study procedures and the data files received from NIMH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: All other authors report no disclosures.

The terms of this arrangement are being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

References

- 1.Khachaturian AS, Corcoran CD, Mayer LS, Zandi PP, Breitner JC Cache County Study I. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 count affects age at onset of Alzheimer disease, but not lifetime susceptibility: The Cache County Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 May;61(5):518–524. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slooter AJ, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, van Harskamp F, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and progression of Alzheimer's disease: the Rotterdam Study. J Neurol. 1999 Apr;246(4):304–308. doi: 10.1007/s004150050351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bracco L, Piccini C, Baccini M, et al. Pattern and progression of cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease: role of premorbid intelligence and ApoE genotype. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24(6):483–491. doi: 10.1159/000111081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martins CA, Oulhaj A, de Jager CA, Williams JH. APOE alleles predict the rate of cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: a nonlinear model. Neurology. 2005 Dec 27;65(12):1888–1893. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000188871.74093.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowe CC, Ellis KA, Rimajova M, et al. Amyloid imaging results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. Neurobiology of aging. 2010 Aug;31(8):1275–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011 May;7(3):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sojkova J, Zhou Y, An Y, et al. Longitudinal patterns of beta-amyloid deposition in nondemented older adults. Arch Neurol. 2011 May;68(5):644–649. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villemagne VL, Pike KE, Chetelat G, et al. Longitudinal assessment of Abeta and cognition in aging and Alzheimer disease. Annals of neurology. 2011 Jan;69(1):181–192. doi: 10.1002/ana.22248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vlassenko AG, Mintun MA, Xiong C, et al. Amyloid-beta plaque growth in cognitively normal adults: longitudinal [11C]Pittsburgh compound B data. Ann Neurol. 2011 Nov;70(5):857–861. doi: 10.1002/ana.22608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiman EM, Chen K, Liu X, et al. Fibrillar amyloid-beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009 Apr 21;106(16):6820–6825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900345106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thambisetty M, Tripaldi R, Riddoch-Contreras J, et al. Proteome-based plasma markers of brain amyloid-beta deposition in non-demented older individuals. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(4):1099–1109. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleisher AS, Chen K, Liu X, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 and age effects on florbetapir positron emission tomography in healthy aging and Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013 Jan;34(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fouquet M, Besson FL, Gonneaud J, La Joie R, Chetelat G. Imaging brain effects of APOE4 in cognitively normal individuals across the lifespan. Neuropsychology review. 2014 Sep;24(3):290–299. doi: 10.1007/s11065-014-9263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Hansson O, et al. CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2009 Jul 22;302(4):385–393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moghekar A, Li S, Lu Y, et al. CSF biomarker changes precede symptom onset of mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2013 Nov 12;81(20):1753–1758. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000435558.98447.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peskind ER, Li G, Shofer J, et al. Age and apolipoprotein E*4 allele effects on cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 42 in adults with normal cognition. Arch Neurol. 2006 Jul;63(7):936–939. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, et al. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Annals of neurology. 67(1):122–131. doi: 10.1002/ana.21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnick SM, Goldszal AF, Davatzikos C, et al. One-year age changes in MRI brain volumes in older adults. Cerebral cortex. 2000 May;10(5):464–472. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Driscoll I, Resnick SM, Troncoso JC, An Y, O'Brien R, Zonderman AB. Impact of Alzheimer's pathology on cognitive trajectories in nondemented elderly. Annals of neurology. 2006 Dec;60(6):688–695. doi: 10.1002/ana.21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawas C, Gray S, Brookmeyer R, Fozard J, Zonderman A. Age-specific incidence rates of Alzheimer's disease: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neurology. 2000 Jun 13;54(11):2072–2077. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.11.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fourth Edition, DSM-IV. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984 Jul;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daly E, Zaitchik D, Copeland M, Schmahmann J, Gunther J, Albert M. Predicting conversion to Alzheimer disease using standardized clinical information. Arch Neurol. 2000 May;57(5):675–680. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002 Jan;15(1):273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y, Resnick SM, Ye W, et al. Using a reference tissue model with spatial constraint to quantify [11C]Pittsburgh compound B PET for early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. NeuroImage. 2007 Jun;36(2):298–312. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hixson JE, Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J Lipid Res. 1990 Mar;31(3):545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Gidicsin CM, et al. Florbetapir (F18-AV-45) PET to assess amyloid burden in Alzheimer's disease dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and normal aging. Alzheimers Dement. 2013 Oct;9(5 Suppl):S72–S83. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, et al. Amyloid beta deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer's disease: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. Neurology. 2013 Apr;12(4):357–367. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albert M, Soldan A, Gottesman R, et al. Cognitive changes preceding clinical symptom onset of mild cognitive impairment and relationship to ApoE genotype. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014;11(8):773–84. doi: 10.2174/156720501108140910121920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]