Abstract

The Ebola virus is a lipid-enveloped virus that obtains its lipid coat from the plasma membrane of the host cell it infects during the budding process. The Ebola virus protein VP40 localizes to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane and forms the viral matrix, which provides the major structure for the Ebola virus particles. VP40 is initially a dimer that rearranges to a hexameric structure that mediates budding. VP40 hexamers and larger filaments have been shown to be stabilized by PI(4,5)P2 in the plasma membrane inner leaflet. Reduction in the plasma membrane levels of PI(4,5)P2 significantly reduce formation of VP40 oligomers and virus-like particles. We investigated the lipid-protein interactions in VP40 hexamers at the plasma membrane. We quantified lipid-lipid self-clustering by calculating the fractional interaction matrix and found that the VP40 hexamer significantly enhances the PI(4,5)P2 clustering. The radial pair distribution functions suggest a strong interaction between PI(4,5)P2 and the VP40 hexamer. The cationic Lys side chains are found to mediate the PIP2 clustering around the protein, with cholesterol filling the space between the interacting PIP2 molecules. These computational studies support recent experimental data and provide new insights into the mechanisms by which VP40 assembles at the plasma membrane inner leaflet, alters membrane curvature, and forms new virus-like particles.

TOC Graphics

Molecular simulations show that the VP40 hexamer strongly interacts with PI(4,5)P2 that results in an enhanced PI(4,5)P2 clustering.

Introduction

The Ebola virus protein VP40 is a peripheral protein that localizes in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (PM)1 and forms the viral matrix which provides the major structure for the virus-like particles (VLP). Formation of the matrix from the assembly and oligomerization of VP40 dimers involves a series of steps. First, a VP40 dimer is trafficked to the plasma membrane where electrostatic interactions occur between the anionic lipids and the basic patch of the VP40 C-terminal domain (CTD). Deletion of several lysine residues in CTD loops prevented VLP formation, even though the dimeric structure was unaltered. Once at the plasma membrane, it has been hypothesized that the VP40 dimers undergo major structural rearrangements and oligomerize into hexameric structures2, 3, which oligomerize to form filaments that associate further to form the viral matrix4. Recently, Soni et al. showed that the VP40-hexamer penetrates deeply (~8 Å) into the PM and causes a significant change in the membrane curvature3. This is important for viral egress, membrane localization and formation of virus-like particles. The residues that penetrate the PM were identified as Leu213, Ile293, Leu295, and Val298 in a loop5 region in the CTD. In another study, membrane rafts were seen to be important in VP40 assembly and oligomerization6. Although the x-ray crystal structures of the dimeric and hexameric forms provide information about structural transformations that must occur, the mechanisms of VP40-membrane interactions leading to the structural transformations from dimers to hexamers and hexamers to larger filamentous structure are not well known.

Different types of phospholipids have been hypothesized to have different roles in VP40 cellular localization, membrane binding and insertion as well as in membrane bending5, 7, 8, 9. For example, phosphatidylserine (PS) was found to be a critical component of VP40 virus-like particle formation and was essential for dimers to form hexamers in live cells7. PS was also found to be exposed on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane in cells expressing VP407 whereas PS is normally only on the inner leaflet of healthy mammalian cells. The exposure of PS on the plasma membrane outer leaflet and that of virus-like particles was consistent with the role of PS in Ebola virus entry10 but somewhat in contrast to the importance of PS in VP40 budding and oligomerization. A more recent study highlighted the role of PI(4,5)P2 in stabilizing the VP40 filaments or oligomers at the inner leaflet of the PM9. This stabilization is a critical step in oligomerization of hexamers into filament structures that form the virus envelope and was hypothesized9 to stabilize the VP40 matrix layer as PS becomes exposed on the outer leaflet. Analyses of the multi-lamellar vesicle (MLV) sedimentation assay showed that the presence of PI(4,5)P2 and PS significantly enhanced the binding of the hexamers to the lamellar vesicles8. As with the Ebola virus, the trafficking of the viral Gag proteins of HIV-1 to the PM is also shown to be mediated by PI(4,5)P211, 12.

To understand the roles of various phospholipids on VP40 hexamer binding in the PM, we performed coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations (CGMD) on the hexamer-membrane system. While all-atom simulations are useful in understanding the temporal and spatial evolution of a system in the nanosecond timescales, they are computationally demanding for investigating physical properties such as lipid diffusion and clustering and protein-membrane interactions that occur on microsecond timescales. The CGMD13, 14, 15, 16 model, which maps four atoms on average to a single interactions site, provides an excellent alternative. This model simplifies the complex energy landscape and enhances the kinetics of the system 16 and has been extensively used in recent investigations on membrane protein and lipid systems17, 18, 19, 20. In one study11, CGMD simulations were found to better represent the protein-membrane binding as compared to other extended-lipid protein-membrane models12. The CG simulations of the highly asymmetric plasma membrane showed the clustering of the Glycolipids GM3 in the outer leaflet and PI(4,5)P2 in the inner leaflet. The different types of lipid clustering affect the membrane bending differently and the correlation of such lipid clustering with the membrane curvature has important biological implications21. For example, Ipsita et al. investigated the clustering of GM1 with or without PSM using CGMD22. It was found that in the presence of PSM, the GM1 domains formed loosely bound clusters, whereas in the absence of PSM, they were more strongly bound in the clusters. Similarly, Koldso et. al showed that local enrichment of PI(4,5)P2 in the inner leaflet can induce concave curvature (viewed from intracellular side) to the plasma membrane.21 This result is directly relevant to our present work because such a membrane curvature is needed for the budding of the Ebola virus particle.

In this work, we investigated the lipid-protein interactions in VP40 hexamers at the PM. We quantified lipid-lipid self-clustering by calculating the fractional interaction matrix and found the VP40 hexamer significantly enhances the PI(4,5)P2 clustering. The radial pair distribution functions also suggest a strong interaction of PI(4,5)P2 with the VP40 hexamer. Our results provide insights on how clustering of PIP2 would stabilize the VP40 oligomers and promote viral budding. For convenience, PI(4,5)P2 is referred to as PIP2 in the rest of the paper.

Methods

A. Hexamer model

The initial x-ray crystal structure of the VP40 hexamer was taken from the protein data bank (PDB) [PDB entry 4ldd]. The hexamer is formed by three dimers that join via their N-terminal domain (NTD) interfaces. The C-terminal domains (CTD) of VP40 at the two ends are intact but the other four CTDs are missing in the crystal structure. Based on the orientations of the dimers in the hexameric structure2, two of the middle CTDs point towards and interact with the membrane, whereas the other two CTDs point towards the cytoplasm. The missing CTDs that interact with the membrane were inserted using Modeller23. These CTDs were oriented in such a way that the hydrophobic residues that are known to penetrate the membrane face towards the membrane3, 24.

B. Plasma membrane model

The membrane-VP40 hexamer system was generated using the Charmm-GUI25 web server. An asymmetric lipid bilayer was generated in accordance with the high complexity of the plasma membrane composition26, 27. The percentage of various lipids (POPC:POPE:PSM:POPS:PIP2:CHOL) in the modeled membrane were (41:8:23:4:4:20) in the outer (or upper) leaflet and (11: 37: 5: 16: 10: 21) in the inner (or lower) leaflet. The lipid-bilayer is generated large enough to accommodate the hexamer. The solvated membrane-protein system contained >600,000 atoms in the all-atom representations, but in the coarse-grained set up, the numbers were significantly reduced as described below. The lipid bilayer without protein was composed with the same ratios of the phospholipid mixture as described above for the bilayer with protein.

C. Simulation setup

For CG simulations, we used the Martini force field in which approximately four heavy atoms are mapped onto a single interaction site (bead), except for the residues with aromatic side chains14. Specifically, Ala and Gly residues are each represented by a single bead; Cys, Asn, Asp, Gln, Glu, Ile, Leu, Met, Pro, Ser, Thr, and Val are each represented by two beads; Arg and Lys are each represented by three beads; His, Phe, and Tyr are each represented by four beads, and Trp is represented by five beads. Similarly for lipids POPC, POPE and POPS each have 12 beads, PIP228 has 16 beads, PSM has 11 beads, and CHOL has 8 CG beads. These beads are divided into four interaction types: Polar (P), nonpolar (N), apolar (C), and charged (Q). There are subtypes d (donor in H-bond), a (acceptor in H-bond), n (none), da (both) and P1 (lower polarity)-P5 (highest polarity)14.

The Martini Maker plugin25 in the Charmm-Gui webserver was used to prepare both the protein-membrane and membrane-only systems. The Martini 2.0 force field was used for lipids with a non-polarizable water model, combined with the elastic network model for the protein (VP40 hexamer). All systems were equilibrated using the six-step equilibration process generated by the Charmm-Gui29. Each system was solvated using standard MARTINI water beads and was neutralized in 0.15 M NaCl. The final protein-membrane system consisted of 52 827 particles and the membrane-only system consisted of 27 512 beads. The number of lipids used for the CGMD simulations is given in Table S1. For one of the simulation setups, the elastic network constraints were removed for all the atoms in the top two CTDs in the middle by setting the spring constant to zero. Various simulations performed in this work are summarized in Table S2.

All CGMD simulations were run using Gromacs5.1.130, 31 (gpu-version). A time step of 15 fs was used and the Lennard-Jones and coulomb potential were cutoff at 11 Å. The Verlet neighbor scheme was used with a straight cutoff to keep track of particles within specified distances32. Coulomb interactions were treated using a reaction-field. Ring systems and stiff bonds were controlled using the LINCS algorithm. The pressure was maintained at 1 bar using the Berendsen barostat during equilibration runs and the Parrinello-Rahman barostat during production runs. Pressure coupling between protein and membrane groups was semi-isotropic with a compressibility of 3x10−4 bar−1. The temperature was maintained at 303.15 K and the temperature coupling was done using a velocity rescale algorithm.

Results

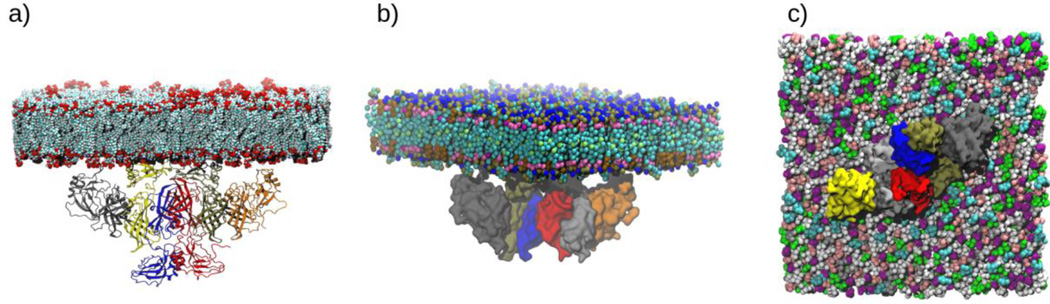

In order to investigate the VP40-membrane interactions, we prepared the hexamer-membrane system with the middle two CTDs facing the lower leaflet of the membrane so that the hydrophobic residues Leu213, Ile293, Leu295, and Val298 in a loop region were in direct contact with the membrane, as predicted by experiments3, 24. The all-atom as well as coarse-grained representations of the system are displayed in Fig. 1. The all-atom representation in Fig. 1a includes the lower CTDs that interact with VP35 proteins that are involved in packaging and incorporating the viral RNA into VLP33. As they do not influence the membrane binding, the lower CTDs were not included in the CGMD simulations (Fig. 1b) to further reduce computational time. The hydrophobic residues in the CTDs that interact with the lower leaflet of the plasma membrane are shown in Fig S1.

Figure 1.

VP40 hexamer-membrane system. a) All-atom representation of VP40 hexamer at the PM lower-leaflet, side view. b) Coarse-grained representation, side view c) Distribution of various lipids in the initial setup, as viewed from the bottom. Lipids are colored as Light-Blue: PIP2, Green: POPC, White: POPE, Gray: PSM, Pink: POPS, Purple: CHOL.

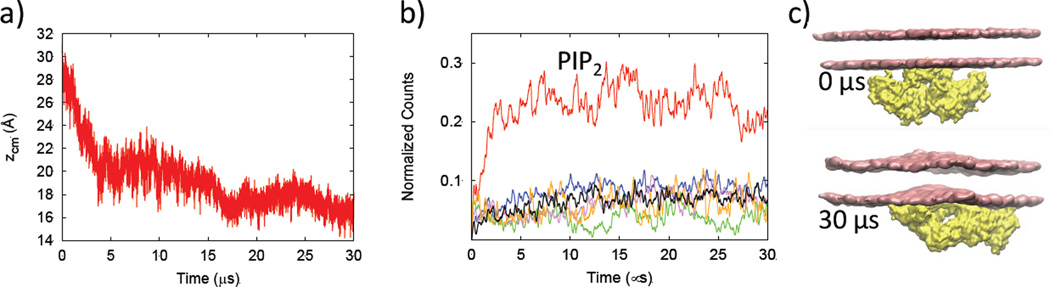

We performed a 30-µs CGMD simulation and monitored the dynamics of the VP40 hexamer-membrane interactions. The initial setup has several amino acids in the middle two CTDs interacting with the membrane. The protein center-of-mass was initially set ~28 Å below the membrane, measured from the z-coordinate of the center of mass of the phosphate beads of the lipid bilayer in the lower leaflet of the plasma membrane. During the MD simulations, the protein diffuses laterally around the lower leaflet and also increases the protein-membrane contacts. After ~ 3 µs, the CTDs at the two ends interact more strongly with the membrane. Figure 2a shows the time evolution of the relative distance zcm between the center of mass of the phosphate beads in the lower leaflet of the plasma membrane and the protein center of mass using the backbone beads. As the two CTDs at the end start to interact strongly with the membrane, zcm is significantly reduced.

Figure 2.

a) Distance between the lipid and protein center of masses (zcm), b) Normalized count of various lipids within 7Å of the VP40 hexamer as a function of time, c) Bending (or bulging) of the membrane due to enhanced lipid-protein interactions.

In Fig. 2b, we display the number of each type of lipid near the VP40 hexamer as a function of time. The normalized count for a lipid type is calculated as the number of that lipid type within 7Å of the protein divided by the total number of that lipid type in the lower leaflet of the PM. Interestingly, PIP2 is the only lipid type that shows significant crowding around the protein. The normalized count for PIP2 increases steadily until ~3 µs and plateaus to a much larger value (~25%) than the normalized counts of the other lipid types (<10%). It is worth noting that the reduction in zcm in Fig. 2a occurs after the occurrence in Fig. 2b of significant PIP2 crowding around the protein. We further investigated the crowding of PIP2 by exploring the lipid clustering in the membrane with or without protein, as discussed below.

Figure 2c (top) shows the initial configuration of the hexamer-membrane setup with a planar lipid bilayer. By the end of 30 µs, a noticeable bulging or bending of the PM is observed (Fig. 2c, bottom). This is because an increase in the number of contacts between the membrane and the end-CTDs cause the hydrophobic residues Leu213, Ile293, Leu295, and Val298 to penetrate further into the membrane. The elastic network constraints in the protein can limit the extent of the membrane penetration. In order to address this, we performed a separate 10 µs simulation in which we removed the elastic constraints for all the beads in the middle two CTDs. This allows the CTD amino acids to adjust their positions and optimize the interactions with the lipid. As shown in Fig. S2, the protein-lipid distance zcm is further reduced and the normalized count of PIP2 near VP40 noticeably increases when the amino acids are allowed to interact without the elastic network constraints.

Lipid clustering in the PM with and without VP40

Different types of mammalian cell plasma membranes have different lipid compositions and the differences in lipid compositions can affect how proteins interact with the membranes34. Through CGMD simulations, it has been shown that certain lipid types tend to cluster in the membrane21. Especially important, the local lipid composition caused by clustering was found to directly affect the membrane curvature21. Since membrane bending is important for VLP formation, we investigated changes in the local lipid composition due to lipid clustering in the presence of the protein.

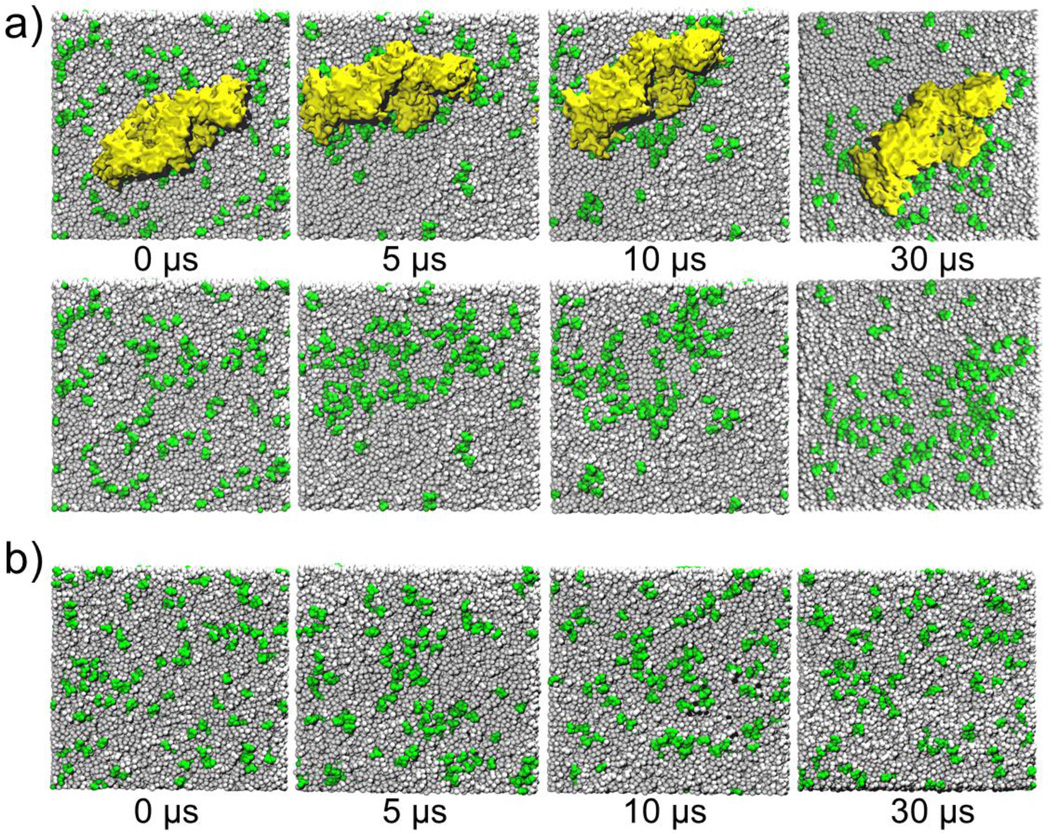

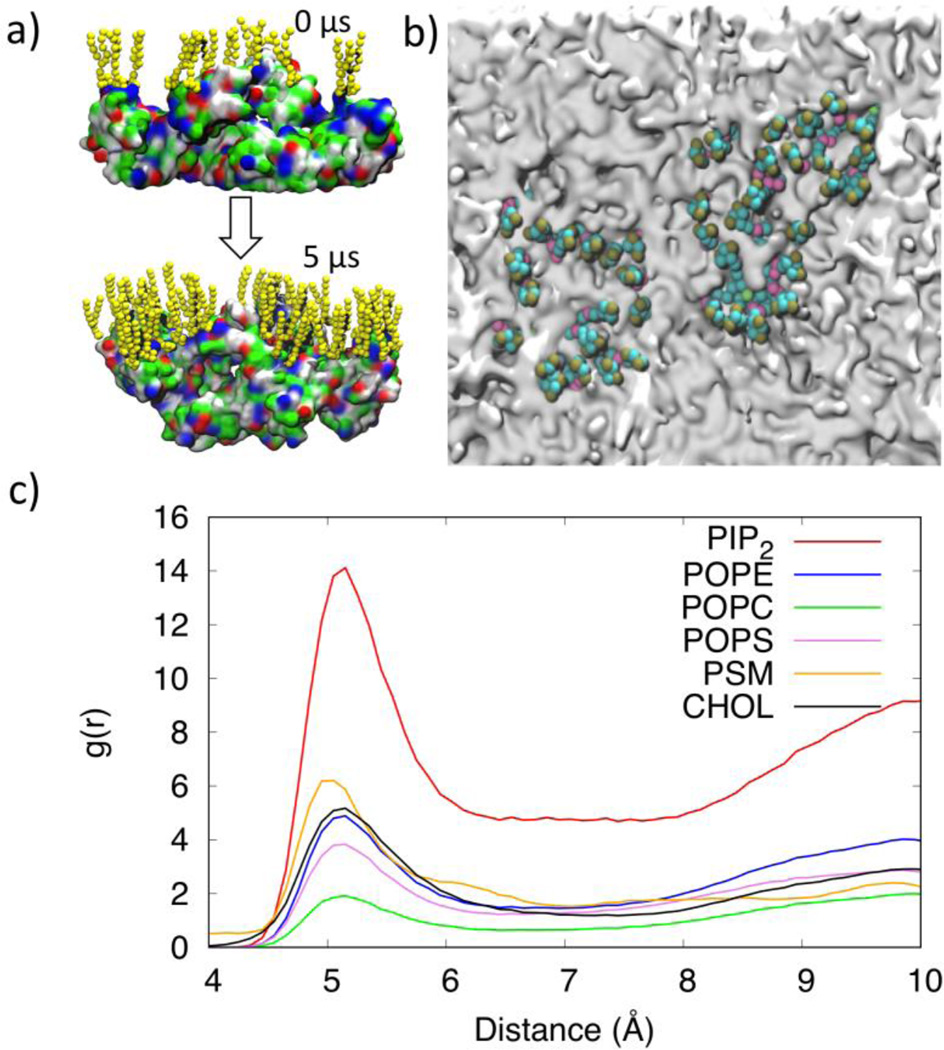

We investigated the distribution of PIP2 in the lower leaflet of the plasma membrane in the presence of the VP40 hexamer and compared it with the distribution of PIP2 without the protein. The top panel of Fig. 3a, displays the VP40 hexamer-membrane systems as viewed from below (cytoplasmic side) at different times. The bottom panel of Fig. 3a displays the same system as in the top panel but with the protein removed to better show the lipid distribution in the membrane. In the beginning (0 µs), the PIP2 lipids are randomly distributed (as generated by Charmm-GUI). By 5 µs, a significant clustering of PIP2 is observed, mostly in the periphery of the protein. Besides PIP2, no other lipid type showed such clustering behavior. To compare the behavior of the lipids in the absence of protein, we performed a 30 µs simulation with only the membrane and display the results in Fig. 3b. Initially (0 µs), the PIP2 lipids are randomly distributed as in Fig. 3a. By the end of the 30 µs simulation, PIP2 shows some clustering but to a significantly lesser extent compared to the clustering in the presence of the protein (Fig.3a)

Figure 3.

Distribution of lipids (PIP2: Green) in the lower leaflet of the plasma membrane. a) Results of the CGMD simulation with the presence of the VP40 hexamer. The top row shows the VP40 hexamer (Yellow), the row below are the same snapshots with the VP40 hexamer removed so that the lipids are visible. b) Results of the CGMD simulation in the absence of a protein.

Upon closer inspection of the PIP2 clusters in the periphery of the protein, we observed that the PIP2 head groups interact strongly with the basic and polar residues in VP40 as shown in Fig. 4a. The locations of the CTDs are noticeable in Fig. 4b as gray areas surrounded by PIP2 lipids (green). We calculated the radial pair distribution function g(r) for the various lipid types relative to the VP40 hexamer. The g(r) quantifies the relative abundance of a specific lipid type around the protein. The distances between amino acid backbone beads and the phosphate groups (PO4 bead in the CGMD)) of lipid molecules in the lower leaflet of the plasma membrane are used to calculate the distribution function. As shown in Fig. 4c, PIP2 molecules significantly cluster around the protein, compared to other lipid types. Lipid types PSM, POPE, POPS and CHOL show only a weak preference to be in contact with the protein, and POPC seems to have the least preference.

Figure 4.

a) Distribution of the PIP2 lipids near the VP40 hexamer at 0 µs and 5 µs showing the negatively charged lipid head groups interacting with the positively charged or polar residues on the protein. b) Clustering of PIP2 lipids within 7Å of VP40. The VP40 was present in the simulation but is removed from the image to allow full view of the membrane. PIP2 molecules cluster around gray regions that are the location of the VP40 CTDs. c) Radial pair distribution functions for various lipid types relative to the VP40 hexamer.

In order to further confirm the PIP2 clustering by VP40, we performed three additional 10-µs CGMD simulations: a rerun of the existing setup (Run0), a run using an initial hexamer conformation obtained from a 10-ns all-atom simulation (Run1), and a run that removed the elastic network interactions for the middle two CTDs (Run2). These simulations are summarized in Table S2. We calculated the VP40-PIP2 radial pair distribution function and compared with g(r) in Fig 4c (Run0). As shown in Fig. S3, all four runs give very similar results for the PIP2-VP40 pair distribution.

Preferential partitioning of lipids (fractional interaction matrix)

To quantitatively compare the distribution and clustering of the lipid molecules with and without VP40, we calculated the fractional interaction matrix21 for the lipids in the lower leaflet of the PM. The fractional interaction matrix, also known as the preferential partitioning of membrane components represents the normalized number of contacts with a specific lipid type and has been used to study lipid phase separation into ordered and disordered domains in various bilayer systems containing peripheral and transmembrane proteins35, as well as phase separations22 and lipid clustering and membrane curvature in various bilayer systems21. The fractional interaction matrix is calculated as

| (1) |

Here, the preferential partitioning pij represents the number of contacts of the lipid type i relative to the lipid type j, normalized over the number of all lipid contacts with the lipid type i. The number of contacts cij is calculated based on the distance between the glycerol ester moiety (GL1/GL2 beads) of POPE, POPC, POPS, PIP2 or amino alcohols (AM1/AM2 beads) of PSM or cholesterol ROH.

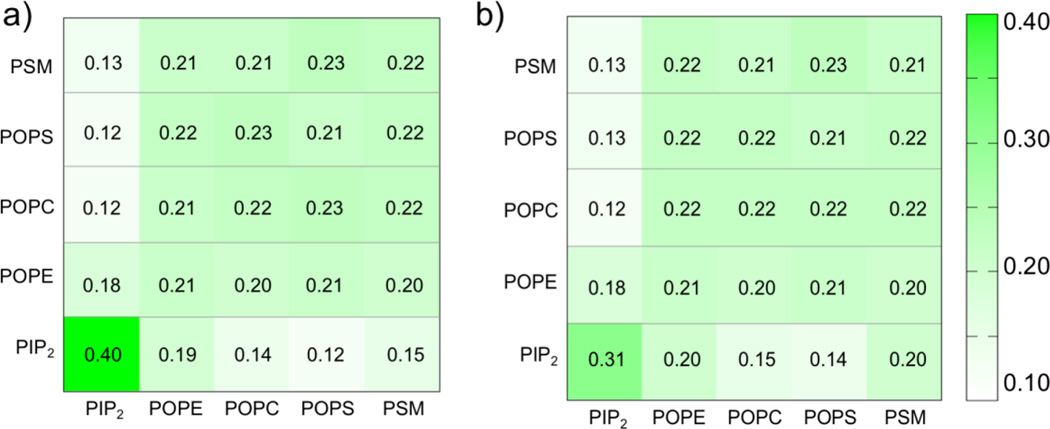

Figure 5a displays the fractional interaction matrix for the five different types of lipids in the lower leaflet of the bilayer containing VP40 hexamer for the last 20 µs of the trajectory. Two lipids are counted as being in contact if they are within 11 Å, which includes both the first and second solvation shells. The fractional interactions of each lipid type with all lipid types are given in the rows, and the values are normalized horizontally. If all five lipid types are randomly distributed, the entries would be 0.20. The fractional interaction for PIP2 with itself (first entry, Row 5) is found to be 0.40, which means that about 40% of the PIP2 contacts are with PIP2 itself and represents clustering. The fractional interactions for any other lipid type (Rows 1-4) are approximately 0.20, indicating randomly distributed lipid contacts. This means that lipid types such as POPE, POPC and PSM each have about the same probability to be in contact with themselves or with other lipid types. POPS is found to have the least preference to be surrounded by PIP2.

Figure 5.

Fractional interaction matrix of lipids in the lower leaflet of the plasma membrane. a) With the VP40 hexamer. b) Without the VP40 hexamer.

To assess any enhancement in lipid clustering due to the VP40 hexamer, we compared the fractional interaction matrices for bilayers systems with and without the protein. Figure 5b displays the fractional interaction matrix for the lipids in the lower leaflet of the membrane-only bilayer system in the absence of VP40. In the absence of the protein, the PIP2-PIP2 fractional contact is 0.31, compared to 0.40 Fig. 5a) in the presence of protein. This suggests that the presence of the VP40 hexamer enhances the PIP2 clustering by ~30%. Such enhancement in PIP2 clustering by VP40 can be functionally important in the viral life-cycle since local clustering of PIP2 in the lower leaflet has been shown to result in curvature of the membrane21.

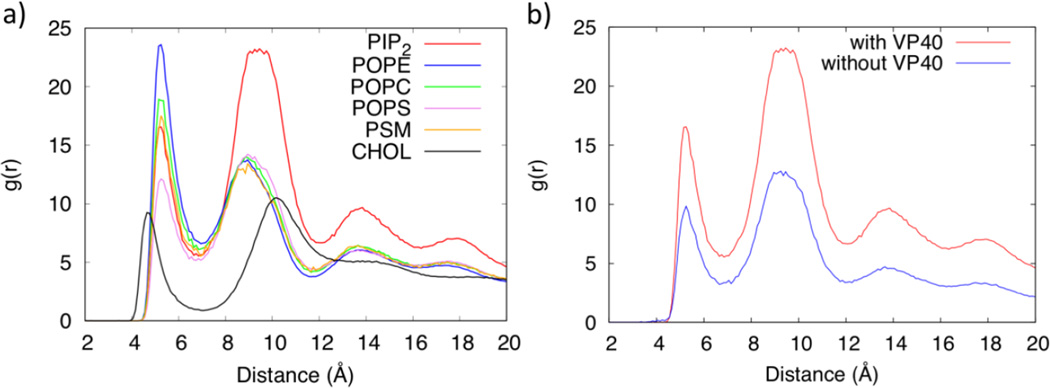

Lipid-lipid radial distribution function

The lipid clustering was further quantified using a radial pair distribution function g(r) for each lipid type. The distances between the phosphate groups (PO4 bead in the CGMD)) of lipid molecules in the lower leaflet of the plasma membrane are used to calculate the distribution function. Figure 6a shows the radial pair distribution functions, which show the probability of lipid self-association (clustering with its own type) and lipid packing for various lipids. Interestingly, POPE, POPC and PSM have a larger distribution function in the first solvation layer with peaks at ~5Å than in their second solvation layer which have peaks around 9Å, whereas PIP2 and POPS have a larger distribution function in the second solvation layer than in the first. The first and second solvation layers for CHOL are more widely spaced with peaks at around 4.5Å and 11Å respectively. CHOL also has slightly more distribution in the second solvation layer, similar to results in previous studies20. The POPC clustering with a larger radial distribution in its first solvation layer shows that it prefers to be surrounded by its own type. In contrast, the larger radial distribution of PIP2 in its second solvation layer suggests that it prefers to be surrounded by other lipid types. This is also evident from Fig. S4 that displays the fractional interaction matrix for lipid contacts within 7Å for the first solvation layer and between 7–11Å for the second solvation layer. The diagonal elements represent clustering with molecules in the same lipid types. We also compared the g(r) for PIP2 with and without the VP40 hexamer in Fig. 6b. The distribution of PIP2 shows a significant enhancement in the lower leaflet in the presence of the protein, compared to the membrane only system. As PIP2 clusters around VP40, the lipids that remain away from the protein also show higher distribution due to the finite size of the simulated system.

Figure 6.

a) Radial distribution function of lipids in the lower leaflet of the plasma membrane. b) Radial distribution functions of PIP2 in the lower leaflet with and without the VP40 hexamer.

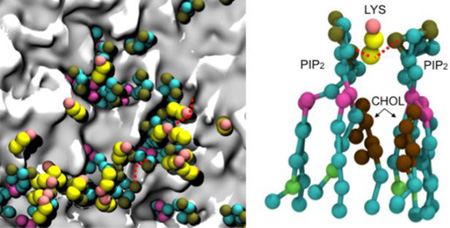

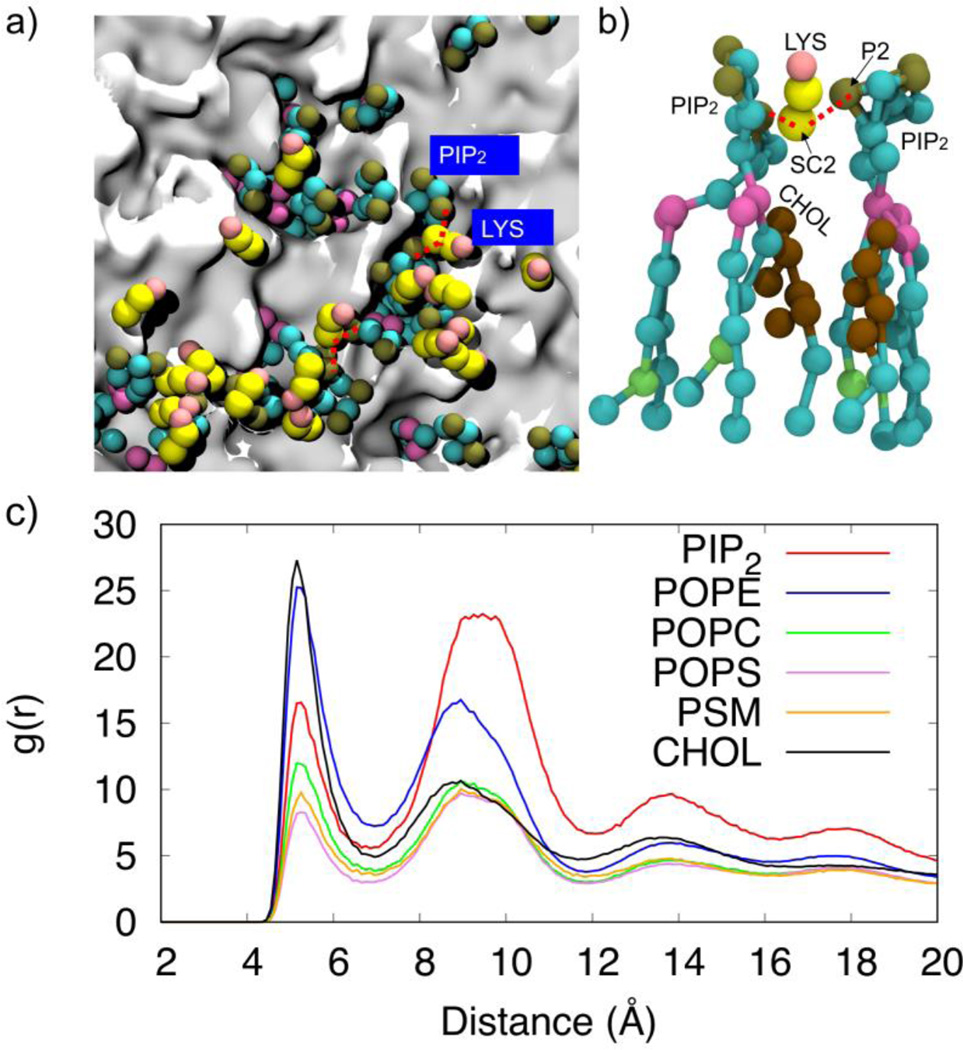

Mechanisms of PIP2 clustering around VP40

PIP2-PIP2 clustering can occur in the plasma membrane due to formation of hydrogen bond networks36 with water molecules and/or Ca2+ that balance the electrostatic repulsion between negatively charged head groups37. We explored the molecular details of the PIP2 interactions leading to PIP2 clustering around VP40 and found that the repulsion between negatively charged phosphate head groups (P1 or P2 beads) can be balanced by the electrostatic attraction mediated by positively charged protein side chains (SC2 bead of Lys and Arg). Figure 7a shows a network of alternating Lys-PIP2 interactions. When a cationic side chain mediates two PIP2 head groups from either side as shown in Fig. 7b, cholesterol molecules are found to fill the space thus created. This also explains why PIP2 has higher self-clustering in the second solvation layer. We calculated the radial pair distribution of PIP2 against all other lipid types and found that cholesterol is the most abundant lipid type around PIP2, followed by POPE. This is reflected in Figure 7c by the high radial pair distribution for PIP2-CHOL. In addition to cholesterol, PIP2 is also significantly surrounded by POPE, due partly to the high percentage of POPE in the membrane, giving a high radial pair distribution for PIP2-POPE (Fig 7c). This also helps in forming a higher PIP2-PIP2 distribution in the second solvation layer.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the role of lysine residues in PIP2 clustering. a) The network of interacting Lys and PIP2. b) Lysine side chains mediating PIP2-PIP2 interactions c) Radial pair distribution function of other lipids around PIP2 lipids

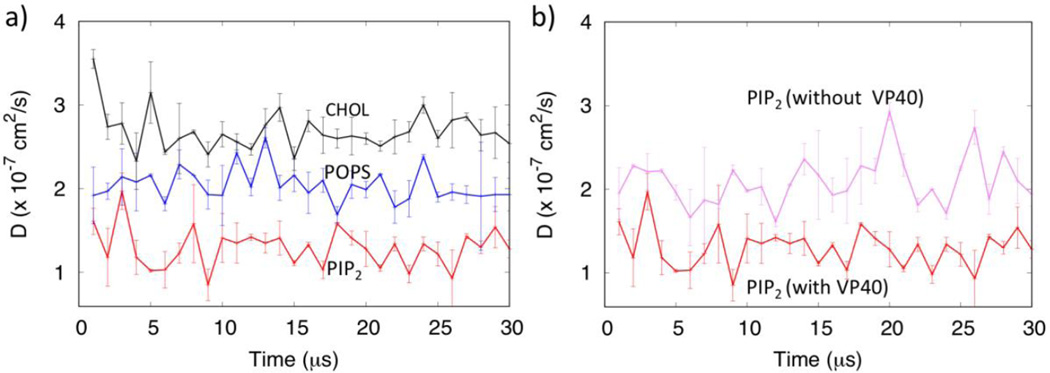

Lipid diffusion and cholesterol flip-flops

The dynamics of the diffusion of lipids can provide information on the formation and recruitment of protein complexes in the membranes17. The lateral movement of lipids molecules in the membrane leads to the formation of liquid ordered and liquid disordered micro domains, which many viruses utilize to attach to activate cell signaling38, 39. We calculated the lateral diffusion coefficients for various lipids with and without the VP40 hexamer during the 30 µs trajectories, averaged every 1 µs time windows, as shown in Fig. 8. As displayed in Fig. 8a, the diffusion coefficients for all lipid types fluctuate, but compared to POPS, PIP2 shows much lower diffusion, reflecting hindered motion due to clustering. Figure 8b shows larger diffusion of PIP2 in the absence of the protein (purple) than with the presence of the protein.

Figure 8.

a) Diffusion of PIP2, POPS and CHOL in the presence of the VP40 hexamer. b) Comparison of the diffusion of PIP2 with and without VP40 hexamer showing the larger PIP2 diffusion (purple) in the membrane only system.

Cholesterol molecules show larger lateral diffusion, compared to both PIP2 and POPS, as shown in Fig. 8a. In addition, we observed significant cholesterol flip-flops between the upper and the lower leaflets, as seen in previous studies21. We show the cholesterol flip-flop in Movie S1 in the Supplementary Information. Initially, the number of cholesterol molecules was 140 in the upper leaflet and 160 in the lower leaflet. As shown in Fig. S5, cholesterol molecules redistribute from the lower to the upper leaflet early in the simulation. At the end of 30 µs, approximately 160 and 140 cholesterol molecules in the upper and lower leaflets, respectively. As the VP40 interacts more strongly with the membrane, the number of cholesterol molecules increase slightly in the lower leaflet, compared to the membrane only system. The functional relevance of the cholesterol flip-flops in VP40 oligomerization is not well understood, but the enrichment of cholesterol in the lower leaflet in the presence of VP40 may have significance. Though cholesterol flip-flop is observed in microsecond timescales, flipping of other lipids require much longer timescales that are not accessible in our simulations. In healthy mammalian cells, PS is normally only on the inner leaflet but it is exposed to the outer leaflet in cells expressing VP407. Actual PS exposure in VP40 expressing cells may require inhibition of these flippases, which maintain the plasma membrane asymmetry with respect to PS in healthy mammalian cells.

Conclusion

We used CGMD simulations to investigate the protein-lipid interactions for the Ebola virus protein VP40 hexamer at the lower leaflet of the plasma membrane. The PIP2 lipid is found to have a tendency to cluster in general, but this clustering is significantly enhanced in the presence of the VP40 hexamer. PIP2 was found to cluster around two CTDs of the VP40 hexamer. Each CTD has a hydrophobic loop that penetrates into the membrane bilayer and lies adjacent to a cationic patch rich in Lys residues. It is found that the electrostatic interactions of negatively charged PIP2 head groups with cationic Lys side chains mediate the PIP2 clustering, with cholesterol filling the space between the PIP2s. The overall mechanism is consistent with the hypothesis that PIP2 stabilizes VP40 oligomers9. PIP2 is likely important for the initial association of VP40 to the plasma membrane bilayer, including formation of VP40 hexamers and larger oligomers from VP40 dimers7. PIP2 then becomes exposed on the plasma membrane outer leaflet as VP40 accumulates on the inner leaflet through a yet to be determined mechanism7. Clustering of PIP2 would provide a mechanism to further concentrate VP40 oligomers and stabilize the underlying VP40 matrix layer, and to promote viral budding by causing membrane bending. Further biophysical investigation is warranted to determine if and how VP40 induces PIP2 clustering in vitro and in cells, how PIP2 contributes to membrane bending, and if cholesterol distribution in the plasma membrane affects VP40 assembly and budding. These studies may also prove useful in determining pharmacological strategies for inhibiting budding of the Ebola virus from the plasma membrane. For instance, therapeutic agents that can modulate membrane curvature or alter membrane fluidity in such a way to reduce plasma membrane bending may be sufficient to slow down the spread of the virus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

VP40 research in the Stahelin lab has been supported by the NIH (AI081077 and AI121841) to R.V.S.

References

- 1.Jasenosky LD, Neumann G, Lukashevich I, Kawaoka Y. J. Virol. 2001;75:5205–5214. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5205-5214.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bornholdt ZA, Noda T, Abelson DM, Halfmann P, Wood MR, Kawaoka Y, Saphire EO. Cell. 2013;154:763–774. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soni SP, Adu-Gyamfi E, Yong SS, Jee CS, Stahelin RV. Biophys. J. 2013;104:1940–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stahelin RV. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2014;18:115–120. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.863877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soni SP, Stahelin RV. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:33590–33597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.586396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panchal RG, Ruthel G, Kenny TA, Kallstrom GH, Lane D, Badie SS, Li L, Bavari S, Aman MJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:15936–15941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2533915100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adu-Gyamfi E, Johnson KA, Fraser ME, Scott JL, Soni SP, Jones KR, Digman MA, Gratton E, Tessier CR, Stahelin RV. J. Virol. 2015;89:9440–9453. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01087-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stahelin RV. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:300. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson KA, Taghon GJ, Scott JL, Stahelin RV. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:19125. doi: 10.1038/srep19125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moller-Tank S, Kondratowicz AS, Davey RA, Rennert PD, Maury W. J. Virol. 2013;87:8327–8341. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01025-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercredi PY, Bucca N, Loeliger B, Gaines CR, Mehta M, Bhargava P, Tedbury PR, Charlier L, Floquet N, Muriaux D, Favard C, Sanders CR, Freed EO, Marchant J, Summers MF. J. Mol. Biol. 2016;428:1637–1655. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlier L, Louet M, Chaloin L, Fuchs P, Martinez J, Muriaux D, Favard C, Floquet N. Biophys. J. 2014;106:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marrink SJ, Risselada HJ, Yefimov S, Tieleman DP, de Vries AH. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monticelli L, Kandasamy SK, Periole X, Larson RG, Tieleman DP, Marrink SJ. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:819–834. doi: 10.1021/ct700324x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marrink SJ, de Vries AH, Mark AE. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:750–760. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marrink SJ, Tieleman DP. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:6801–6822. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60093a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goose JE, Sansom MS. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1003033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koldso H, Sansom MS. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:3498–3502. doi: 10.1021/jz301570w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nawae W, Hannongbua S, Ruengjitchatchawalya M. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:3933. doi: 10.1038/srep03933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Risselada HJ, Marrink SJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:17367–17372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807527105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koldso H, Shorthouse D, Helie J, Sansom MS. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basu I, Mukhopadhyay C. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17:17130–17139. doi: 10.1039/c5cp01970b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eswar N, Webb B, Marti-Renom MA, Madhusudhan MS, Eramian D, Shen MY, Pieper U, Sali A. Current protocols in bioinformatics / editoral board, Andreas D. Baxevanis et al. 2006 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0506s15. Chapter 5, Unit 5 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adu-Gyamfi E, Soni SP, Xue Y, Digman MA, Gratton E, Stahelin RV. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:5779–5789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.443960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi Y, Ingolfsson HI, Cheng X, Lee J, Marrink SJ, Im W. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:4486–4494. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zachowski A. Biochem. J. 1993;294:1–14. doi: 10.1042/bj2940001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Nature Rev. Mol. cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingolfsson HI, Melo MN, van Eerden FJ, Arnarez C, Lopez CA, Wassenaar TA, Periole X, de Vries AH, Tieleman DP, Marrink SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14554–14559. doi: 10.1021/ja507832e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, Im W. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJ. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, Lindahl E. SoftwareX. 2015:1–2. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Jong DH, Baoukina S, Ingólfsson HI, Marrink SJ. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2016;199:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson RF, McCarthy SE, Godlewski PJ, Harty RN. J. Virol. 2006;80:5135–5144. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01857-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharpe HJ, Stevens TJ, Munro S. Cell. 2010;142:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Jong DH, Lopez CA, Marrink SJ. Faraday Discuss. 2013;161:347–363. doi: 10.1039/c2fd20086d. discussion 419-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levental I, Cebers A, Janmey PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9025–9030. doi: 10.1021/ja800948c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang YH, Collins A, Guo L, Smith-Dupont KB, Gai F, Svitkina T, Janmey PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:3387–3395. doi: 10.1021/ja208640t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marsh M, Helenius A. Cell. 2006;124:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coyne CB, Bergelson JM. Cell. 2006;124:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.