ASBTRACT

The spread of infectious disease represents a global threat and therefore remains a priority on the international public health agenda. The International Health Regulations (IHR) (2005) came into effect in June 2007 and provide a legal framework to which the 196 member states of the World Health Assembly agree to abide.1 These regulations include implementation of protective, control and response measures at points of entry to a country (i.e. land borders, sea and airports), and of notification measures, all of which aim to prevent or limit the spread of disease while minimising disruption to international trade.

The World Health Organization can apply and enforce IHR (2005) to any disease considered to pose a significant threat to international public health. This short paper focuses on 2 diseases; yellow fever and poliomyelitis, both of which have the potential to spread internationally. It will discuss the measures applied under IHR (2005) to minimize the threat, and explore the implications for both travelers and travel health advisors.

KEYWORDS: International Health Regulations, Public Health Emergency of International Concern, poliomyelitis, World Health Organization, yellow fever

Yellow fever

Yellow fever (YF) is caused by a virus of the Flaviviridae family, which circulates between infected monkeys or humans and mosquitoes. The infection may be asymptomatic or mild, or can cause serious illness including life threatening hemorrhagic fever. Treatment is supportive. YF is a risk in tropical parts of Africa, South America, eastern Panama in Central America and Trinidad in the Caribbean. The epidemiology of YF is dynamic; outbreaks may occur after long periods of virus inactivity (sometimes years) and risk areas may expand during large outbreaks.

Maps of areas where YF is a risk are available on the individual country pages at http://travelhealthpro.org.uk/country-information/.

YF is a vaccine preventable disease. The vaccine is live, attenuated and well tolerated by most people. Vaccination-induced serious adverse events such as viscerotropic or neurotropic disease occur only rarely, but death has been reported. Healthcare professionals discussing YF with a traveler need to be aware of the 2 separate issues of 1) recommendation for vaccination (for personal protection) and 2) requirement for an International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP) as a condition of entry to a (receiving) country.

All travelers to countries where YF occurs should have an individual risk assessment and be offered YF vaccination for personal protection, unless medically contraindicated. Recommendations for YF vaccination and risk countries are listed by the WHO2,3 and this information is disseminated consistently and widely in the public domain (e.g. by the National Travel Health Network and Centre, Health Protection Scotland and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Following the conclusions of the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE), it is now accepted that YF vaccination confers at least 35 y and likely lifelong protection in most people, and that a booster dose is not needed, with a few exceptions,4,5

An International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP) is issued at the time of vaccination and this document is considered under IHR (2005) to be proof of YF vaccination.1

WHO Member States are required on request, to submit to the WHO entry requirements relating to YF. Entry requirements fall into the following categories:

No ICVP required (wherever you arrive from);

ICVP required if arriving from a country with risk of yellow fever (as listed by the WHO,2,3 or sometimes not on the WHO list, but defined by the receiving country);

ICVP required if transiting a country with risk of yellow fever where transit has been for over 12 hours (variables relating to transit exist);

ICVP mandatory (i.e., required wherever you arrive from, risk country or not).

The requirements of each country are also listed by the WHO.2,3

Historically, the ICVP for yellow fever was considered to be valid for 10 y. Although YF is specifically designated under IHR (2005) and the regulations that apply are well established, significant changes, particularly relating to the duration of validity of ICVP under IHR (2005) take place during 2016. Validity of the ICVP will come into line with the conclusions of SAGE that the vaccine confers lifelong protection,4 and therefore, following vaccination an ICVP will have a lifelong validity.3,4 All member states were required to submit a statement of their interpretation of the SAGE conclusions and hence the length of validity of ICVP by 10 July, 2016.

The WHO have stated:3

From 11 July 2016 the period of validity of ICVP will change from 10 y to life of the person vaccinated, including for certificates already issued and new certificates;

As of 11 July 2016, valid ICVP presented by arriving travelers cannot be rejected on the ground that more than 10 y have passed since the date vaccination became effective as stated on the certificate; boosters or revaccination cannot be required’

It is hoped that all member states will comply with this guidance. However, health professionals should be mindful that changes at country level regarding the accepted period of validity of ICVP may take time and some countries have already indicated that they do not accept a life-long validity of the ICVP. Healthcare professionals should be prepared to advise travelers accordingly. In addition, country requirements may be subject to change, particularly at times of large disease outbreaks in a region and such changes may not always be reflected at WHO level. In these circumstances health professionals are encouraged to use a real time resource for information on current advice regarding recommendations and requirement for vaccination.

Poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis (polio) is caused by a human enterovirus called the poliovirus which is transmitted from person-to-person usually faeco-orally. There are three serotypes of wild poliovirus (WPV) – type 1, type 2, and type three. The last wild type 2 poliovirus was detected in India in 1999. Type 1 and type 3 WPV continue to circulate in endemic areas. Both are very infectious and can cause paralytic polio. Vaccine-derived polioviruses (VDPVs) are rare strains of poliovirus that have genetically mutated from the strain contained in the oral polio vaccine.6

Polio mainly affects children under 5 y of age, and most infections are asymptomatic or very mild, but 1 in 200 infections can lead to paralysis and death in 5% to 10% of cases.

As most infections are asymptomatic, the virus can be “silently” spread in unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated populations before the first case of polio paralysis is identified. Polio or suspected polio is a notifiable disease under IHR (2005),7 and the WHO considers a single confirmed case of polio paralysis, including VDPV to be an outbreak, particularly in countries where very few cases occur.6,7

In 1988, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution for the worldwide eradication of polio and launched the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. The strategy to eradicate polio is based on preventing infection by immunizing every child to stop transmission and ultimately make the world polio free.6 Polio vaccination is included in national immunisation programmes throughout the world, with most children receiving a primary course of either inactivated (parenteral) or live (oral) tri or bivalent vaccine (as of April 2016, oral trivalent vaccine will be replaced by oral bivalent vaccine in a globally synchronised switch, removing the type 2 component of the vaccine from global immunisation programmes).6 Oral vaccine (OPV) is inexpensive, safe for immune-competent individuals and effective, inducing long lasting immunity in the recipient and passive immunity in close contacts. However, rarely, it can cause vaccine associated paralytic polio (VAPP). Occasionally the excreted live vaccine virus may change and in an under immunised population, circulate (cVDPV). Inactivated vaccine carries no risk of paralytic polio and confers an excellent protective immune response. However, inactivated vaccine is costly and only induces low immunity in the intestine, and therefore does not confer passive immunity in a population. High levels of vaccination coverage must be maintained to stop transmission and prevent outbreaks.6

All travelers to a country reporting polio cases should be up to date with their national schedule vaccinations, including polio and should be offered a booster if more than 10 y have elapsed since their last dose.8

At the time of writing, polio remains endemic in only two countries Afghanistan and Pakistan, although case numbers are declining.9 However, as long as cases continue to be reported, all countries, especially vulnerable countries with poor infrastructures and/or trade and travel links with endemic countries will remain at risk of importation of polio.

As well as the risk from WPV, outbreaks of cVDPV are of concern; currently outbreaks are occurring in Guinea, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Madagascar, Myanmar, Nigeria and Ukraine.10

IHR (2005) have only recently been applied to polio infection; in May 2014, following notification of international spread of poliovirus and the acknowledgment that travelers contributed to this spread, an Emergency Committee of the WHO declared that under IHR (2005) the international spread of WPV represented a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).11 Temporary recommendations were made under PHEIC for countries reporting cases and/or exporting the virus to reduce the potential for spread. These measures, reviewed every 3 months, are a global public health initiative, with the aim of interrupting international spread of polio viruses (shown in Table 1.)

Table 1.

WHO PHEIC implications (adapted from Simons & Patel 201512)10,12 (Listed countries as of 12 May 2016; countries listed are subject to change).

| Country status | Traveler status | Recommendation for polio vaccination | International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP) | Other record of polio vaccination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infected and exporting WPV or cVDPV Afghanistan, Pakistan10 | Residents, including visitors who have lived in the country for > 4 weeks where last dose of polio vaccine was >12 months before date of departure | Yes: between 4 weeks and 12 months before leaving the infected country | Yes: required to be presented at point of departure frominfected country and may be required for visa application and/or on entry to a receiving country | No |

| Infected, but not exporting WPV or cVDPV Nigeria, Guinea, Madagascar, Ukraine, Lao People's Democratic Republic and Myanmar10 | Residents, including visitors who have lived in the country for > 4 weeks where last dose of polio vaccine was >12 months before date of departure | Yes: between 4 weeks and 12 months before leaving the infected country | No | Yes: encouraged to obtain appropriate proof of polio vaccination |

| Polio-free countries | Traveling to WPV infected country (which is exporting the virus) for more than 4 weeks | All travelers should ensure they have completed an age appropriate polio vaccination schedule according to their national immunisation schedule. In addition: consider a booster dose of polio containing vaccine before departing polio-free country based on national guidelines | No | Proof of vaccination may be required to be presented on departure from infected country |

Health professionals discussing polio with a traveler need to be conversant with the 2 separate issues of the recommendation of vaccination for personal protection and requirement for an ICVP as a condition of exit from a country under PHEIC (see Table 1). Unlike the requirement for YF vaccination, in the case of polio, under IHR (2005), the need for vaccination applies only to those exiting rather than entering a country. Health professionals must also be mindful that for some travelers (i.e., pregnant or immune compromised) it may not be appropriate to receive OPV, the vaccine of choice in endemic countries.

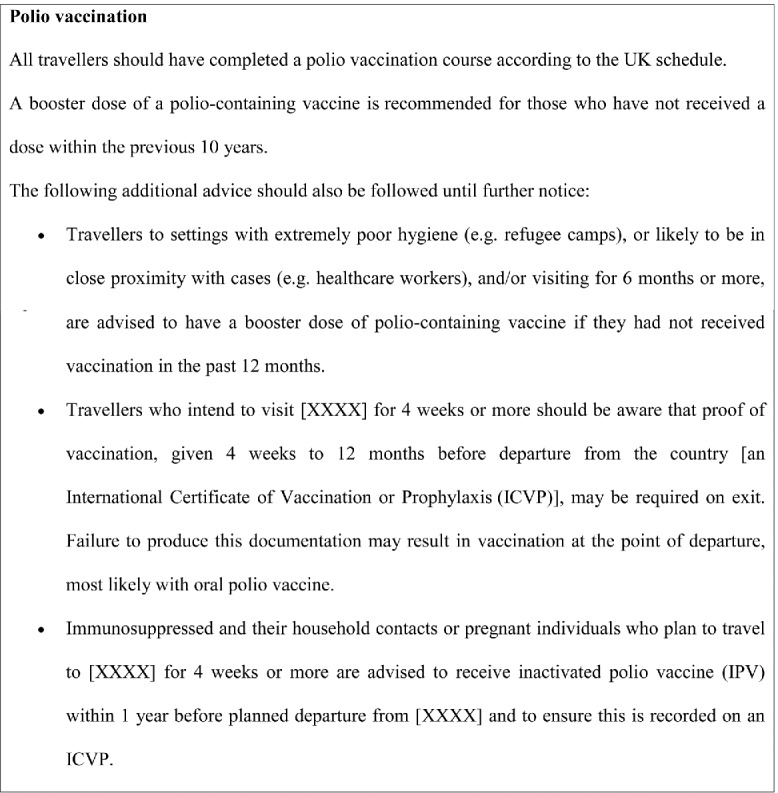

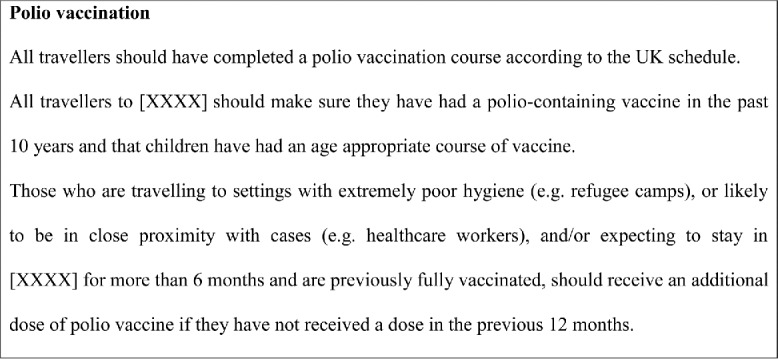

While the PHEIC recommendations have no direct public health benefit to the UK, and are unlikely to impact on personal risk for UK travelers if national travel guidance is followed, to support the WHO and to avoid the possibility of UK travelers experiencing difficulties when departing WPV infected countries (and being revaccinated if unable to prove vaccination within the last year) a pragmatic approach was adopted in England Wales and Northern Ireland. This involved making health professionals and travelers aware of the WHO recommendations and implications in affected countries and for WPV infected countries to follow the guidance in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

National Travel Health Network and Center (NaTHNaC) / Public Health England - Polio vaccination recommendation: countries exporting WPV or cVDPV.1,3

Figure 2.

NaTHNaC/Public Health England – Polio vaccination recommendation: countries infected with WPV or cVDPV but not currently exporting.13

The most recent meeting of the Emergency Committee under the IHR (2005) took place in May 2016 and concluded that the international spread of polio continues to constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). The Committee was asked to reassess the situation within the next 3 months.10

Conclusion

In the context of travel advice, travel vaccinations are generally recommended for the protection of the traveler. This is a concept that is easily understood by both healthcare professional and traveler alike. However, under IHR, vaccinations may also be required for public health benefit, a subtle but significant difference. Healthcare professionals and travelers need to understand this, together with the important role of measures implemented under IHR (2005), as part of the strategy to prevent the international spread of diseases and to protect global public health.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- [1].World Health Organization International Health Regulations (2005). 2nd Edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43883/1/9789241580410_eng.pdf. Last accessed June2016. [Google Scholar]

- [2].World Health Organization International Travel and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. Available from http://www.who.int/ith/en/. Last accessed June2016. [Google Scholar]

- [3].World Health Organization International Travel and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. Annex 1 Countries with risk of yellow fever transmission and countries requiring yellow fever vaccination Available from: http://www.who.int/ith/2016-ith-annex1.pdf?ua=1. Last accessed June2016. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, April 2013 - conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2013; 88(20):201-6; PMID:23696983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Public Health England Immunisation against infectious disease. 2013. Chapter 35. Yellow fever; p 443-456. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book. Last accessed June2016.

- [6].Global Polio Eradication Initiative http://www.polioeradication.org/. Last accessed June2016. [Google Scholar]

- [7].World Health Organization Case definitions for the four diseases requiring notification in all circumstances under the International Health Regulations (2005). [Geneva: ]. Available from: http://www.who.int/ihr/Case_Definitions.pdf. Last accessed June2016. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Public Health England Immunisation against infectious disease. 2013. Chapter 26. Polio. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book. Last accessed June2016.

- [9].World Health Organization Poliomyelitis; Report by the Secretariat. Sixty-ninth World Health Assembly 16 April 2016. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_25-en.pdf. Last accessed June2016.

- [10].World Health Organization Statement on the 9th IHR Emergency Committee meeting regarding the international spread of poliovirus. 12 May 2016. Available from: http://who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2016/ihr-poliovirus-spread/en/. Last accessed June2016. [Google Scholar]

- [11].World Health Organization Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee concerning the international spread of wild poliovirus. 5 May 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2014/polio-20140505/en/. Last accessed June2016. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Simons H, Patel D. Polio in Pakistan-A public health event of international concern with implications for travellers' vaccination. Travel Med Infect Dis 2015; 13(5):357-9; PMID:26433685; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].National Travel Health Network and Centre Country information pages. Available from: http://travelhealthpro.org.uk/country-information/. Last accessed June2016. [Google Scholar]