ABSTRACT

Mobile applications have the potential to influence vaccination behavior, including on-time vaccination. We sought to determine whether the use of a mobile immunization app was associated with the likelihood of reporting on-time vaccination in a cohort of 50 childbearing women. In this pilot study, we describe participant reported app use, knowledge, attitudes or beliefs regarding pediatric vaccination and technology readiness index (TRI) scores.

To explore if app use is associated with change in attitudes, beliefs or behavior, participants were instructed complete a baseline survey at recruitment then download the app. A follow up survey followed 6-months later, reexamining concepts from the first survey as well as collecting participant TRI scores. Changes in Likert scores between pre and post survey questions were compared and multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between TRI score and select survey responses. Thirty-two percent of participants perceived that the app made them more likely to vaccinate on time. We found some individuals' attitudes toward vaccines improved, some became less supportive and in others there was no change. The mean participant TRI score was 3.25(IQR 0.78) out of a maximum score of 5, indicating a moderate level of technological adoption among the study cohort population. While the app was well received, these preliminary results showed participant attitudes toward vaccination moved dichotomously. Barriers to adoption remain in both usability and accessibility of mobile solutions, which are in part dependent on the user's innate characteristics such as technology readiness.

KEYWORDS: attitudes and behaviors, immunization, knowledge, mobile technology, pediatric vaccination, vaccine hesitancy

Introduction

On time vaccination in children is critical to protect against vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs). Falling vaccination rates and increasing prevalence of delayed or off-schedule administration of immunizations has created an environment susceptible to the spread of once eliminated VPDs.1,2

The literature identifies key reasons why people tend not to vaccinate, or do not vaccinate their children on time. These include concerns regarding vaccine safety, challenges understanding complex immunization schedules, logistical issues related to attending appointments and beliefs that VPDs are rare.3,4 Recently, other emerging themes such as increases in individualism and fear of immune system overload have been documented.5,6 Technological interventions have shown promise in addressing these issues while increasing adherence to on-time vaccination.7-9 Specifically, the use of mobile telephones and SMS recall/reminder notifications have been shown to increase immunization coverage in children, adolescents and adults for various vaccinations in multiple settings, including clinics and primary care.10-15 However, SMS character limitations as well as frequently changing telephone numbers over time can present challenges, particularly as individuals are increasingly mobile and often receive their vaccines from multiple providers. In 2014, we developed ImmunizeCA as a free, Pan-Canadian immunization app for both iOS and Android platforms which provided Canadians a tool to manage their and their family's immunizations on their mobile device.16,17 The app allows users to create a profile for each family member, which generates a customized immunization schedule based on their age, sex and jurisdiction. Reminder/recall notifications alert users of upcoming or overdue immunizations through the devices operating systems calendar. ImmunizeCA also has an embedded VPD outbreak map, powered by Harvard's HealthMap, which alerts users of VPD outbreaks in their area and notifies them if any of the individuals whose profiles are in the app are at risk.18

The most recent Canadian Childhood National Immunization Survey found that at 2 years old, coverage for measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus were, in many instances, below what is needed to achieve herd immunity.19 In addition, almost 70% of parents expressed concerns regarding the side effects of vaccines, and over a third believed that a vaccine can cause the same disease it was meant to prevent. By providing accurate information on vaccinations, helping to schedule and remind parents of vaccination appointments and notifying individuals of VPD outbreaks, ImmunizeCA may address several of the potential reasons for suboptimal compliance to on-time vaccinations.20

However, only individuals who are willing to embrace new technologies will benefit from apps like ImmunizeCA. The Technology Readiness Index (TRI) has served as a tool for measuring peoples' propensity to adopt a new technology to accomplish daily tasks. A higher TRI score generally represents someone more likely to adopt such mediums and trust that they will help fulfill their goals.

The objective of this study was to determine whether use of ImmunizeCA was associated with individuals self-reporting an increased likelihood for on-time vaccination for their child or children of a cohort of childbearing women. We also sought to determine usefulness and usage of ImmunizeCA, participant movement of knowledge, attitudes or beliefs regarding pediatric vaccination, and technology readiness of the users.

Results

Recruitment

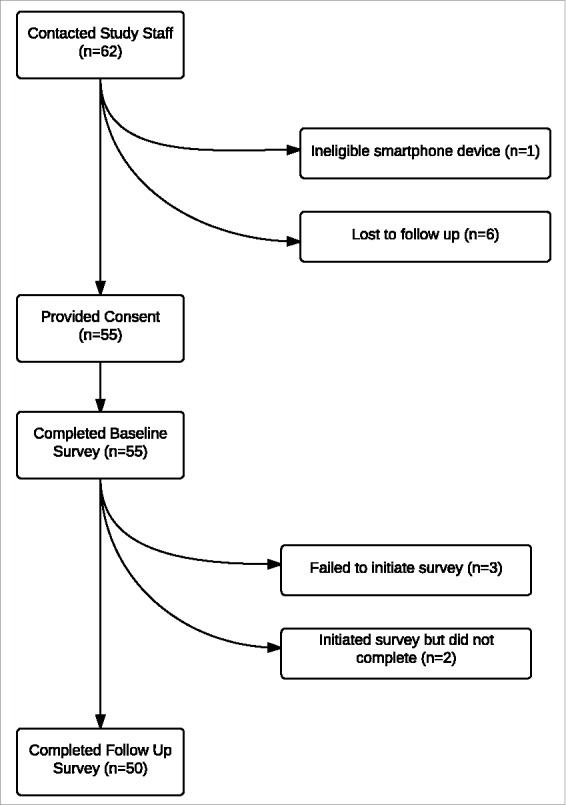

A total of 62 women contacted study staff expressing interest in participating in the study (Fig. 1). One woman was deemed ineligible due to the smartphone device she used (Blackberry Q10) and an additional 6 women did not provide consent to participate. In total, 55 women provided consent and completed the first survey.20 When it was time to complete the follow-up survey, 3 participants failed to initiate the survey online, and 2 more initiated but did not complete. Therefore, our final sample consisted of 50 participants, a completion rate of 80.6%. Those who did not complete both surveys were demographically similar to the larger group in all other measures captured by the survey.

Figure 1.

Study recruitment.

Demographics

The mean age of the study population was 32 years (Table 1). Over two thirds (68%) of the participants were first-time mothers and 96% indicated they were married or in a common-law relationship. Nearly all (93%) had completed a post-secondary diploma or degree.

Table 1.

Demographics of study participants.

| Measure | Participants (n = 50) |

|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 32.2 (23 – 42) |

| First Time mother, n (%) | |

| Yes | 33 (66.0) |

| No | 17 (34.0) |

| Number of previous children, n (%): | |

| 0 | 34 (68.0) |

| 1 | 11 (22.0) |

| 2 | 3 (6.0) |

| 3 | 2 (4.0) |

| Relationship Status, n (%): | |

| Married or common-law | 48 (96.0) |

| Dating | 0 (0.0) |

| Divorced/Separated | 0 (0.0) |

| Single | 1 (2.0) |

| Unanswered | 1 (2.0) |

| I will seek health care for my child(ren) from the following sources, n(%): ** Family Doctor | 41 (82.0) |

| Pediatrician | 18 (36.0) |

| Nurse Practitioner | 9 (18.0) |

| Complementary and Alternative Medicine Provider | 6 (12.0) |

| My highest education level attained, n (%) | |

| <High School | 0 (0.0) |

| High School | 1 (2.0) |

| Some post-secondary | 2 (4.0) |

| Community college/ technical school diploma | 7 (14.0) |

| Undergraduate Degree | 20 (40.0) |

| Graduate Degree | 20 (40.0) |

| My Current Occupation Status**, n (%) | |

| Not employed outside of the home | 6 (12.0) |

| Student | 1 (2.0) |

| Employed Part-time | 4 (8.0) |

| Employed Full-time | 36 (72.0) |

| Self employed | 2 (4.0) |

| Maternity Leave | 3 (6.0) |

| Smartphone, n (%) | |

| Apple iPhone | 34 (68.0) |

| Android | 13 (26.0) |

| Other | 3 (6.0) |

| How many apps do you have on your smartphone? n (%) | |

| Less than 10 | 8 (16.0) |

| Between 10 and 20 | 30 (60.0) |

| More than 20 | 12 (24.0) |

| How many of your smartphone apps are related to pregnancy or child care? n (%) | |

| Less than 10 | 39 (78.0) |

| Between 10 and 20 | 10 (20.0) |

| More than 20 | 1 (2.0) |

| In the last year, have you made a purchase online in the amount of (select all that apply) n (%) | |

| Less than $10 | 11 (22.0) |

| Between $10-$100 | 19 (38.0) |

| More than $100 | 29 (58.0) |

| How many times a day do you check your smartphone? n (%) | |

| Every 5 minutes | 0 (0.0) |

| Every 15–20 minutes | 14 (28.0) |

| Hourly | 20 (40.0) |

| Every 2–3 hours | 13 (26.0) |

| Daily | 3 (6.0) |

Over two-thirds of participants (68%) were using an Apple iPhone, 26% an Android device and 6% responded with “Other.” More than half had between 10 and 20 apps on their smartphone, and 20% had between 10 and 20 apps related to pregnancy and childcare alone. Almost half of participants (40%) reported checking their smartphone devices hourly (Table 1).

When asked to identify all of the type(s) of health care provider(s) involved in their child's health care, 82% mentioned a family doctor, 36% saw a pediatrician, 18% a nurse practitioner and 12% sought care from alternative and complementary medicine providers.

Vaccination decision-making and record keeping

Almost all (96%) of participants reported vaccinating their child, as well as on time according to their provincial immunization schedule (90%). Lots of participants (70%) chose to keep their paper yellow card updated at all appointments, although some ended up with more than one yellow card (8%) and others did not use paper cards at all (16%).

ImmunizeCA use and usability

More than one third (36%) of participants always used the ImmunizeCA app to track their child's immunization records with varying use of appointment reminders (38% using often or always, rarely or never by 50%) (Table 2). Over half (62%) of participants reported often or always finding that the information in the app was encompassing and that they didn't have to look for further information from other sources.

Table 2.

Participant responses to survey questions pertaining to ImmunizeCA app usage.

| Survey Question | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I used the ImmunizeCA app to track my baby's vaccination records | 34% | 10% | 10% | 10% | 36% |

| I used the ImmunizeCA app to access information regarding vaccines | 26% | 10% | 46% | 14% | 4% |

| I used the ImmunizeCA app to obtain information regarding outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases in my area | 62% | 6% | 24% | 4% | 4% |

| I used the ImmunizeCA app to remind myself of upcoming vaccination appointments | 42% | 8% | 12% | 28% | 10$ |

| I used the ImmunizeCA app to access immunization fact sheets | 34% | 22% | 30% | 8% | 6% |

| The ImmunizeCA app provided reliable and trustworthy information | 16% | 2% | 18% | 26% | 38% |

| The information provided on the ImmunizeCA app was encompassing. I did not have to look for further information elsewhere | 14% | 2% | 22% | 40% | 22% |

| I trusted information from the ImmunizeCA app | 12% | 0% | 8% | 30% | 50% |

Eighty-six percent of participants reported that overall they believed the app was easy to use while 8% reported having problems using the app (Table 3). Only ten percent of participants reported having password protected their app, and 6 percent having any concerns with the privacy and security of information entered into the app.

Table 3.

Participant responses to survey questions pertaining to app acceptability and ease of use.

| Survey Question | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| I am more likely to vaccinate my child / children on time because of the ImmunizeCA app | 32% | 68% |

| I password protected my ImmunizeCA app | 10% | 90% |

| I was concerned about the privacy and security of the information I entered in the ImmunizeCA app | 6% | 94% |

| Overall, do you believe ImmunizeCA is easy to use? | 86% | 14% |

| I had problems using the app | 8% | 92% |

| I have or will recommended using the app to other/new parents | 72% | 28% |

| I used the app to track my own vaccinations and/or my other children's vaccination records | 36% | 64% |

| I plan on continuing to use the ImmunizeCA app in the future | 72% | 28% |

Technology readiness index

The median TRI score was 3.25 (IQR 0.78) out of a maximum score of 5, indicating a moderate level of technological adoption among study cohort participants. The median scores for innovativeness and optimism were 3.75 (IQR 0.75) and 3.0 (IQR 1). Median scores for inhibiting dimensions, insecurity and discomfort were 2.3 (IQR 1.0) and 3.25 (IQR 0.75) respectively. In the multivariate analysis there was evidence of an association between the “insecurity” parameter and response to the question “I am more likely to vaccinate my child / children on time because of the ImmunizeCA app” (Odds Ratio 4.33; Confidence Interval 1.26– 14.94; p = 0.02) suggesting lower insecurity was associated with increased likelihood of vaccinating on time. No other associations in the multivariate analysis were significant.

Change in attitudes toward vaccination over time

Approximately a third (32%) of participants perceived that the app made them more likely to vaccinate on time (Table 3).

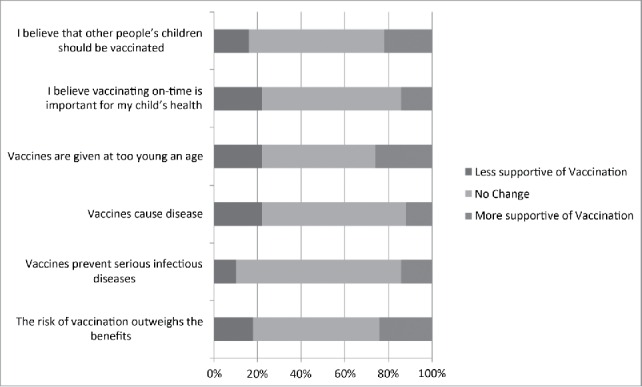

In the follow-up survey, 18 percent of participants were more in agreement that the risk of vaccination outweighs the benefits and 24% were less in agreement than they reported to be in the baseline survey (Fig. 2, Table 4). We did not identify any significant change in beliefs from pre to post intervention (Table 5). However, we did notice different directions of movement among individual participants. For example, 14 percent of participants were more in agreement with the statement that vaccines prevent serious infectious diseases and 10% were less in agreement with this statement. When asked if they agreed with the statement “Vaccines cause disease,” 12 percent were less in agreement than at baseline and 22% were more in agreement than at baseline. Twenty-six percent were less in agreement with the statement “Vaccines are given at too young an age” in the follow-up survey and 22% were more in agreement. We found that 14% were more in agreement with the statement “I believe vaccinating on time is important for my child's health” in the follow-up survey and 22% became less convinced that vaccinating on time is important for their child's health.

Figure 2.

Percentage of participants who experienced shifts in their responses to the survey questions at follow up.

Table 4.

Pre-survey responses and mean score regarding participant knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward vaccination.

| Pre Survey Aggregate Responses | Strongly Disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Neither Agree nor Disagree (3) | Agree (4) | Strongly Agree (5) | Mean score | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The risk of vaccination outweighs the benefits | 19(38%) | 16(32%) | 2(4%) | 2(4%) | 11(22%) | 2.40 | 50 |

| 2. Vaccines prevent serious infectious diseases | 0 | 0 | 2(4%) | 14(28%) | 34(68%) | 4.64 | 50 |

| 3. Vaccines cause diseases | 30(60%) | 14(28%) | 3(6%) | 1(2%) | 1(2%) | 1.55 | 49 |

| 4. Vaccines are given at too young an age | 17(34%) | 16(32%) | 9(18%) | 4(8%) | 4(8%) | 2.24 | 50 |

| 5. I believe vaccinating on-time is important for my child's health | 2(4%) | 2(4%) | 3(6%) | 11(22%) | 32(64%) | 4.38 | 50 |

| 6. I believe that other people's children should be vaccinated | 0 | 0 | 6(24%) | 19(38%) | 25(50%) | 4.38 | 50 |

| Post Survey Aggregate Responses | Strongly Disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Neither Agree nor Disagree (3) | Agree (4) | Strongly Agree (5) | Mean Score | Total |

| 1. The risk of vaccination outweighs the benefits | 23(46%) | 7(14%) | 2(4%) | 6(12%) | 12(24%) | 2.54 | 50 |

| 2. Vaccines prevent serious infectious diseases | 1(2%) | 0 | 1(2%) | 11(22%) | 37(74%) | 4.66 | 50 |

| 3. Vaccines cause diseases | 26(52%) | 19(38%) | 3(6%) | 1(2%) | 1(2%) | 1.64 | 50 |

| 4. Vaccines are given at too young an age | 15(30%) | 22(44%) | 8(16%) | 1(2%) | 4(8%) | 2.14 | 50 |

| 5. I believe vaccinating on-time is important for my child's health | 2(4%) | 3(6%) | 4(8%) | 14(28%) | 27(54%) | 4.22 | 50 |

| 6. I believe that other people's children should be vaccinated | 0 | 1(2%) | 5(10%) | 16(32%) | 28(56%) | 4.42 | 50 |

1 participant did not provide a response for presurvey question 3 (n = 49)

Table 5.

P = values for all pre/post survey questions regarding participant knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward vaccination.

| Question | Mean change post - pre | p-value (sign test) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. The risk of vaccination outweighs the benefits | 0.14 | 0.66 |

| 2. Vaccines prevent serious infectious diseases | 0.02 | 0.77 |

| 3. Vaccines cause diseases | 0.08 | 0.33 |

| 4. Vaccines are given at too young an age | −0.10 | 0.84 |

| 5. I believe vaccinating on-time is important for my child's health | −0.16 | 0.48 |

| 6. I believe that other people's children should be vaccinated | 0.04 | 0.65 |

Discussion

In this study we examined the impact of a mobile immunization app on likelihood of self-reported on-time pediatric vaccination in a cohort of childbearing women. We also examined usage and usability of the app, impact on attitudes toward vaccination and technology readiness. A high percentage of participants indicated that they vaccinated their children on-time according to the current provincial schedule. One third of participants stated that the app increased the likelihood of consistent on-time pediatric vaccination. In general, usability of the app was considered good. Interestingly, we found that while some individual's attitudes toward vaccination improved in a positive direction, on some there was no impact and, on others there was actually a move toward being less supportive of vaccinations.

The findings in our pilot study may indicate a potential value in using a mobile app to improve vaccination rates as almost a quarter (24%) of participants had multiple or no paper cards recording vaccinations by the follow up period of 6 months. Furthermore, a quarter of individuals also reported seeking care from non-physicians, with a third planning to seek healthcare from more than one provider, all of which can make tracking of vaccinations challenging for parents.

While the app may address challenges to vaccination in society, barriers to adoption include usability and accessibility. Generally, participants found the app easy to use, though less than half reported using it for tracking and reminder purposes. Our median participant TRI score was 3.25 (IQR 0.78), slightly higher than the reported means in 2012 and 1999, at 3.025 and 2.88 respectively. As our study used a convenience sample of participants, it is logical that they would be more technologically ready than the general population.

When examining motivating dimensions, it is interesting to note that participant median scores for innovativeness was the same as the mean reported in the 2012 validation (3.75). However, the median scores for the optimism dimension was 3 (IQR 1), lower than the mean scores reported in 1999 and 2012, at 3.84 and 3.75 respectively. This may indicate that while our participants were innovative, a trait of early adopters, their lower than average score in the dimension of optimism may be driving suboptimal usage of such features as tracking and reminders in an app.

Examining inhibitor scores reveals that our participants also differ from population means, particularly in the dimension of insecurity. Our participants median score for insecurity was at 2.3 (IQR 1.0) compared to population averages of 4.03 and 3.58 in 1999 and 2012. This suggests that overall, our participants are less concerned about the negative consequences of technology compared to the general population, and thus willing to engage with new mobile apps. This observation is consistent with survey responses where only 6% of participants cited concerns regarding privacy of personal health information residing in a mobile app. In addition, our multivariate analysis found an association between those who scored lower in the dimension of insecurity, and those reporting that the app helped them vaccinate on time. These results, adjusted for age, first time mother status and level of education are in line with other studies which have found that insecurity can impact the perceived ease of use, and in some cases the perceived usefulness of new technologies, both driving early adoption.21,22 In light of the new digital era, the connection between low insecurity and early adoption may be a key finding for digital health. We propose that those who are low in insecurity may be the most amenable to using new technologies for behavior change, as they are less likely to distrust technology and perceive negative consequences from its use.

The app's impact on change in attitudes about vaccination is of further interest. We found that app use was associated with both increased and decreased support for vaccines. Dichotomous effects on attitudes could be secondary to small sample size, test-retest reliability. Movement toward negative vaccine attitudes could also be secondary to a natural attrition of attitudes that occur after childbirth, coupled with exposure to conflicting information about vaccinations. However, our findings are consistent with previous studies which have shown that exposure to information intended to positively influence individuals to vaccinate can actually dissuade individuals from vaccinating.23,24 Thus, the possibility of exposure to any information on vaccines, even through an app, could make individuals more concerned about vaccination. This unexpected observation deserves further examination in future studies.

This study has important strengths and limitations. This is the largest sample of surveys for a parent facing immunization app and of Technology Readiness Index scores of parents or patients in a health care context. We are aware of one other study which examined the feasibility of using a smartphone application for immunization.25 This study by Peck et al recruited a convenience sample of parents and caregivers from a pediatric primary care office to evaluate their perception of “Call the Shots,” an Android smartphone application that delivered recall/reminders for vaccinations as well as supplemental information on vaccination. Although they reported positive initial results, the sample (n = 6) was insufficient to evaluate the usefulness of the app. The authors recommended expanding the app's availability to both Android and iPhones to improve recruitment rates.

Similar to the study by Peck et al, our study is limited by sample size. It was not adequately powered to identify smaller but potentially important levels of change in attitudes over time, or to identify predictors of responses. The study also was used a convenience sample of participants in a before and after design, offering preliminary evidence to future studies and the basis for larger RCTs. The absence of a control group made it difficult to determine the impact of the app compared to normal changes in attitudes that would occur over the same period. Due to technological constraints, we relied on self-report of on-time vaccination. As per standardized practice in Ontario, parentally reported vaccinations are considered the source of truth, and parents are required to report to public health for school entry under the immunization of school pupils act.26

Mobile devices are becoming ubiquitous, generating opportunities to improve multiple aspects of future vaccination practices.27,28 Understanding individual variability in adoption and usage of mobile health apps will be important to inform the effective development and dissemination of digital health solutions.

Materials and methods

Study population

Our study population included consenting women aged 18 years and older, who spoke English and owned a compatible smartphone (iPhone, Android or Blackberry Z10). Participants were eligible to participate if they, at the time of recruitment, were in their third trimester of pregnancy or had given birth within the last 3 months. Participants were recruited over a 9-month period (November 2013 – July 2014) from the Obstetrics-Gynecology Unit at The Ottawa Hospital - Civic campus using a combination of active and passive methods. Passive methods used included displaying posters describing the study in the hospital's obstetrical units, ultrasound waiting rooms and obstetrician offices. In parallel, active methods of recruitment were used, such as short presentations at prenatal information sessions held at the Civic campus, snowball sampling and study handouts given by physicians and clinical managers at their discretion. Following participant recruitment, informed consent was obtained on paper, or online, and participants were instructed to seek and download the ImmunizeCA app prior to completing the baseline survey.

Data collection tools

A baseline and follow-up survey were developed and pilot tested on 5 women. Minor changes were made to the surveys to improve clarity, and those results were not included in the final analysis. Baseline surveys were completed shortly after recruitment, either on paper, or online through SurveyMonkey software.29

Baseline survey (n = 54)

The baseline survey consisted of 32 questions, capturing participant demographics (age, relationship status, employment status, education level, type of health care provider, and pregnancy history). A 5-point Likert scale was employed in the hopes of examining existing attitudes, beliefs and behaviors related to pediatric vaccination. The survey further collected information on participant's mobile app usage behaviors20

Follow-up survey (n = 50)

The follow-up survey consisted of 37 questions on a 5-point Likert scale plus an additional 16 questions for the technology readiness index (TRI) 2.0,30 for a total of 53 questions. The survey began by re-examining participant attitudes and behaviors regarding pediatric vaccination collected in the baseline survey. These became the variables used for the multivariate regression models. Then, the survey inquired about the sources of health care sought for the newborn, methods of vaccination record keeping, attitudes toward usage and usability of ImmunizeCA, and the user's intent to recommend and continue using the app beyond the study period. App use was collected through self-report as the mobile app data resided on the device and the technological capacity did not exist to passively track individual study participant use. Finally, the survey measured participant mobile device usage and TRI 2.0, an individual's innate propensity to adopt and utilize a new technology to achieve a goal in home or work life. All 16 TRI questions are measured on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from the lowest possible score of 1.0 (strongly disagree) to the highest, 5.0 (strongly agree), where 3.0 is considered neutral. As per the below equation, a higher TRI score indicates a higher level of technology readiness. The scale measures 4 dimensions, through 4 questions per dimension. Two of the dimensions are motivating; innovativeness and optimism, and 2 are inhibiting; discomfort and insecurity.30,31 Innovativeness is described as “a tendency to be a technology pioneer and a thought leader.” Optimism is the degree to which an individual possesses a “positive view of technology and a belief that it offers people increased control, flexibility, and efficiency in their lives.” Insecurity is a general “distrust of technology and skepticism about its ability to work properly.” Finally, discomfort is “a perceived lack of control over technology and a feeling of being overwhelmed by it.”

Statistical analysis

Changes in Likert scores between pre and post surveys were compared, demonstrating a shift in attitudes either in favor or against vaccination. A multivariate logistic regression was utilized to assess the relationship between the composite TRI score and its individual dimensions, to obtain the following responses: (1) I am more likely to vaccinate my child / children on time because of the ImmunizeCA app and (2) I plan on continuing to use the ImmunizeCA app in the future.

Conclusions

We found that although the ImmunizeCA app was well received, participant attitudes toward pediatric vaccination moved dichotomously. Some participants became more favorable, while others became less likely to vaccinate. Yet, of those that did utilize the app, it was deemed helpful in improving on-time vaccination. Participant TRI scores can help elucidate motivators and inhibitors to app adoption and utilization. Reasons for dichotomous impact need to be studied in randomized controlled trials but our results suggest that there is value to further evaluating the use of mobile apps for immunization.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

KA and KW were involved in the development and release of ImmunizeCA.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the ImmunizeCA team; Developers Cameron Bell, Julien Guerinet, and Yulric Sequeria, our partners at CPHA, Greg Penney, Chandni Sondagar and at ImmunizeCanada, a coalition of CPHA, Lucie Marisa Bucci.

Funding

We would like to thank the PHAC/CIHR Influenza Research network (PCIRN) and the Public Health Agency of Canada for their contributions to our research.

References

- [1].Majumder MS, Cohn EL, Mekaru SR, Huston JE, Brownstein JS. Substandard Vaccination Compliance and the 2015 Measles Outbreak. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169(5):494-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gahr P, DeVries AS, Wallace G, Miller C, Kenyon C, Sweet K, Martin K, White K, Bagstad E, Hooker C, et al.. An outbreak of measles in an undervaccinated community. Pediatrics 2014; 134(1):e220-e28; PMID:24913790; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1542/peds.2013-4260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mills E, Jadad AR, Ross C, Wilson K. Systematic review of qualitative studies exploring parental beliefs and attitudes toward childhood vaccination identifies common barriers to vaccination. J Clin Epidemiol 2005; 58:1081-88; PMID:16223649; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dawson B, Apte SH. Measles outbreaks in Australia: obstacles to vaccination. Aust N Z J Public Health 2015; 39:104-6; PMID:25715740; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/1753-6405.12328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hilton S, Petticrew M, Hunt K. Combined vaccines are like a sudden onslaught to the body's immune system': Parental concerns about vaccine ‘overload’and ‘immune-vulnerability’. Vaccine 2006; 24:4321-27; PMID:16581162; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Blume S. Anti-vaccination movements and their interpretations. Soc Sci Med 2006; 62:628-42; PMID:16039769; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen L, Wang W, Du X, van Velthoven MH, Yang R, Zhang L, Koepsell JC, Li Y, Wu Q, et al.. Effectiveness of a smart phone app on improving immunization of children in rural Sichuan Province, China: study protocol for a paired cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2014; 14:262; PMID:24645829; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2458-14-262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jacobson Vann JC, Szilagyi P. Patient reminder and patient recall systems to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005(3):CD003941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Odone A, Ferrari A, Spagnoli F, Visciarelli S, Shefer A, Pasquarella C, Signorelli C. Effectiveness of interventions that apply new media to improve vaccine uptake and vaccine coverage: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015; 11:72-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kharbanda EO, Stockwell MS, Fox HW, Andres R, Lara M, Rickert VI. Text message reminders to promote human papillomavirus vaccination. Vaccine 2011; 29:2537-41; PMID:21300094; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Stockwell MS, Kharbanda EO, Martinez RA, et al.. Text4Health: impact of text message reminder–recalls for pediatric and adolescent immunizations. Ame J Public Health 2012; 102:e15-e21; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stockwell MS, Kharbanda EO, Martinez RA, Vargas CY, Vawdrey DK, Camargo S. Effect of a Text Messaging Intervention on Influenza Vaccination in an Urban, Low-Income Pediatric and Adolescent Population A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2012; 307:1702-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.2012.502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Stockwell MS, Westhoff C, Kharbanda EO, Vargas CY, Carmago S, Vawdrey DK, Castaño PM. Influenza Vaccine Text Message Reminders for Urban, Low-Income Pregnant Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Public Health 2014; 104(Suppl 1(0)):e1-e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Leeb A, Regan AK, Peters IJ, Leeb C, Leeb G, Efflet PV. Using automated text messages to monitor adverse events following immunisation in general practice. Med J Aust 2014; 200:416-8; PMID:24794676; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5694/mja13.11166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jordan ET, Bushar JA, Kendrick JS, Johnson P, Wang J. Encouraging influenza vaccination among Text4baby pregnant women and mothers. Am J Prev Med 2015; 49:563-72; PMID:26232904; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Immunize Canada ImmunizeCA App. http://immunize.ca/en/app.aspx [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wilson K, Atkinson KM, Penney G. Development and release of a national immunization app for Canada (ImmunizeCA). Vaccine 2015; 33:1629-32; PMID:25704801; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Health Map http://healthmap.org/en/ Accessed January20, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- [19].Public Health Agency of Canada Childhood National Immunization Coverage Survey, 2013. Accessed February2, 2016 http://healthycanadians.gc.ca/publications/healthy-living-vie-saine/immunization-coverage-children-2013-couverture-vaccinale-enfants/index-eng.php [Google Scholar]

- [20].Atkinson KM, Ducharme R, Westeinde J, Wilson SE, Deeks SL, Pascalo D, Wilson K. Vaccination attitudes and mobile readiness: A survey of expectant and new mothers. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015; 11:1039-45; PMID:25714388; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/21645515.2015.1009807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kuo K-M, Liu C-F, Ma C-C. An investigation of the effect of nurses' technology readiness on the acceptance of mobile electronic medical record systems. BMC Med Inf & Decision Making 2013; 13:88; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1472-6947-13-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Walczuch R, Lemmink J, Streukens S. The effect of service employees' technology readiness on technology acceptance. Information & Management 2007; 44:206-15; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.im.2006.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wilson K, Mills EJ, Norman G, Tomlinson G. Changing attitudes towards polio vaccination: a randomized trial of an evidence-based presentation versus a presentation from a polio survivor. Vaccine 2005; 23:3010-15; PMID:15811647; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, Freed GL. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2014; 133:e835-e42; PMID:24590751; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1542/peds.2013-2365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Peck JL, Stanton M, Reynolds GE. Smartphone preventive health care: Parental use of an immunization reminder system. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 2014; 28:35-42; PMID:23195652; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pedhc.2012.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Immunization of School Pupils Act. RSO 1990 c. I.1. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wilson K, Atkinson KM, Deeks SL, et al.. Improving vaccine registries through mobile technologies: a vision for mobile enhanced Immunization information systems. JAMIA 2016; 23:207-11; PMID:26078414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wilson K, Atkinson KM, Westeinde J. Apps for immunization: Leveraging mobile devices to place the individual at the center of care. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015; 11:2395-99; PMID:26110351; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/21645515.2015.1057362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].SurveyMonkey.com Survey Monkey. 2014. Available from:http://www.surveymonkey.com/. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Parasuraman A, Colby CL. An updated and streamlined technology readiness index TRI 2.0. J Service Res 2015; 18(1):59–74 [Google Scholar]

- [31].Parasuraman A. Technology Readiness Index (TRI) a multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. J Service Res 2000; 2:307-20; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/109467050024001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.