Abstract

BACKGROUND

Studies have suggested an association between frequent acetaminophen use and asthma-related complications among children, leading some physicians to recommend that acetaminophen be avoided in children with asthma; however, appropriately designed trials evaluating this association in children are lacking.

METHODS

In a multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial, we enrolled 300 children (age range, 12 to 59 months) with mild persistent asthma and assigned them to receive either acetaminophen or ibuprofen when needed for the alleviation of fever or pain over the course of 48 weeks. The primary outcome was the number of asthma exacerbations that led to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids. Children in both treatment groups received standardized asthma-controller therapies that were used in a simultaneous, factorially linked trial.

RESULTS

Participants received a median of 5.5 doses (interquartile range, 1.0 to 15.0) of trial medication; there was no significant between-group difference in the median number of doses received (P = 0.47). The number of asthma exacerbations did not differ significantly between the two groups, with a mean of 0.81 per participant with acetaminophen and 0.87 per participant with ibuprofen over 46 weeks of follow-up (relative rate of asthma exacerbations in the acetaminophen group vs. the ibuprofen group, 0.94; 95% confidence interval, 0.69 to 1.28; P = 0.67). In the acetaminophen group, 49% of participants had at least one asthma exacerbation and 21% had at least two, as compared with 47% and 24%, respectively, in the ibuprofen group. Similarly, no significant differences were detected between acetaminophen and ibuprofen with respect to the percentage of asthma-control days (85.8% and 86.8%, respectively; P = 0.50), use of an albuterol rescue inhaler (2.8 and 3.0 inhalations per week, respectively; P = 0.69), unscheduled health care utilization for asthma (0.75 and 0.76 episodes per participant, respectively; P = 0.94), or adverse events.

CONCLUSIONS

Among young children with mild persistent asthma, as-needed use of acetaminophen was not shown to be associated with a higher incidence of asthma exacerbations or worse asthma control than was as-needed use of ibuprofen. (Funded by the National Institutes of Health; AVICA ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01606319.)

Many children younger than 12 years of age receive acetaminophen each week, making it the most commonly used pediatric medication in the United States.1 Observational data from both pediatric and adult cohorts have suggested an association between acetaminophen use and concurrent asthma symptoms and decreased lung function.2–6 Furthermore, a post hoc analysis of a randomized trial on the safety of short-term use of acetaminophen versus ibuprofen for febrile illnesses in children similarly showed that the relative risk of unscheduled visits for asthma after the use of acetaminophen was substantially higher than the risk after the use of ibuprofen.7 These findings have led to much controversy and even alarm; some physicians have recommended that until data supporting its safety become available, acetaminophen should be completely avoided in children with asthma.8 However, observational studies and post hoc analyses are prone to bias and confounding by indication,9 and appropriately designed randomized trials that have prospectively evaluated the association between the standard use of acetaminophen for children and asthma symptoms in a well-characterized cohort are lacking. Given that both acetaminophen and ibuprofen are commonly used and are the only readily available agents for fever or pain in young children, we sought to investigate in a blinded, randomized trial whether the use of acetaminophen, when clinically indicated, was associated with higher morbidity related to asthma than that with ibuprofen, among children 12 to 59 months of age who have mild persistent asthma.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND OVERSIGHT

The Acetaminophen versus Ibuprofen in Children with Asthma (AVICA) trial was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel trial that was conducted from March 2013 through April 2015. The study included a run-in period of 2 to 8 weeks, with the duration of the run-in period varying according to the severity of asthma symptoms at presentation and prior exposure to asthma medication; the run-in period was followed by randomization to one of two antipyretic, analgesic medications, acetaminophen or ibuprofen. In the Individualized Therapy for Asthma in Toddlers (INFANT) trial — a simultaneous, factorially linked, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, triple-crossover trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01606306) — the participants received standardized asthma-controller therapies that included daily use of inhaled glucocorticoids (fluticasone propionate, two inhalations at 44 μg each, twice daily), daily use of an oral leukotriene-receptor antagonist (montelukast, 4 mg, once daily at bedtime), and as-needed use of inhaled glucocorticoids (fluticasone propionate, two inhalations at 44 μg each, with each use of open-label albuterol sulfate) (further details of the INFANT trial are provided in the AVICA protocol, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). After the run-in phase was completed, children underwent randomization in a two-step process — one to determine the sequence of asthma-controller therapy in the INFANT trial and the other to determine the antipyretic, analgesic medication assignment in the AVICA trial. The assigned antipyretic, analgesic medications were then administered to the participants by the caregivers in a blinded manner and on an as-needed basis over the course of the 48-week trial.

The Asthma Network (AsthmaNet) of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) funded the study and convened an independent data and safety monitoring board, which monitored the trial and reviewed the primary analyses. The protocol was developed by the AsthmaNet Steering Committee and was approved by an NHLBI protocol review committee and data and safety monitoring board, as well as the institutional review board at each participating site. NHLBI program officers participated in the study design, conduct of the trial, and interpretation of the data. The manufacturers of the trial medications had no input in the design of the study, the accrual or interpretation of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript. All the authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses and for the fidelity of this report to the trial protocol. Parents or legal guardians provided written informed consent for all trial participants.

SITES AND PARTICIPANTS

The trial was conducted at 18 sites in the United States. Children 12 to 59 months of age were eligible if they met the criteria for receiving long-term step 2 asthma-controller therapy, as defined in Expert Panel Report 3 from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program.10 Step 2 asthma-controller therapy (low-dose inhaled glucocorticoids, montelukast, or cromolyn) is recommended for children who meet the clinical criteria for mild persistent asthma (i.e., symptoms on more than 2 days per week, but not daily). Children were excluded if they had any history of an adverse reaction to any of the trial medications or if there was evidence that they might show poor adherence to the trial medication regimens or study procedures. Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the protocol.

STUDY MEDICATIONS

Acetaminophen suspension (160 mg per 5 ml; Little Fevers by Little Remedies [grape flavor], Medtech Products) and ibuprofen suspension (100 mg per 5 ml; Children’s Advil [grape flavor], Pfizer Consumer Healthcare) were purchased in liquid form that had similar taste and appearance to maintain double blinding. Furthermore, the medications were taken out of their original packaging and placed in new packaging that had identical appearance for the two treatment groups. The data coordinating center at Penn State College of Medicine purchased and prepared the trial medications and dosing devices. Standard dosing devices were provided to the parents or legal guardians, who were instructed on the proper use. Parents or legal guardians were also provided with clear oral and written instructions for administering the medication according to the typical indicated use in home care as needed for pain, fever, or discomfort, with no more than one dose every 6 hours.

The dosing strategy was in accordance with dosing guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics.11 Acetaminophen was administered at a dose of 15 mg per kilogram of body weight every 6 hours as needed, and ibuprofen was administered at a dose of 9.4 mg per kilogram every 6 hours as needed. This dosing strategy ensured that the volume of a single dose of either trial medication was the same (0.47 ml per kilogram per dose) so that the study personnel would remain unaware of the treatment-group assignments.

An adequate amount of trial medication was dispensed to the parents or legal guardians, who were unaware of the treatment-group assignments, at each clinic visit on the basis of the child’s weight. At each assessment point during the course of the trial, parents or legal guardians reported medication use either in person or by telephone. In addition to monitoring the quantity of trial medications, diaries and questionnaires were used to track the timing and reasons for the use of the trial medication (e.g., fever, pain, upper respiratory tract infection, or other reason). At each return visit to the clinic, parents or legal guardians returned their unused medication supply and received a new supply. Because acetaminophen and ibuprofen are widely available over the counter, open-label administration of these medications was also assessed every 4 weeks at each assessment point.

OUTCOME MEASURES

The primary outcome was the number of asthma exacerbations per participant. An asthma exacerbation was defined as a clinically significant increase in asthma symptoms that led to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids (oral, intravenous, or intramuscular). A list of the criteria for treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org.

Prespecified secondary outcomes included the percentage of asthma-control days, the average use of rescue albuterol, and the frequency of unscheduled health care utilization for asthma. Asthma-control days were defined as full calendar days without the use of rescue medications for asthma, daytime asthma symptoms, nocturnal asthma symptoms, and unscheduled health care visits for asthma. Caregivers recorded symptoms and the use of rescue albuterol daily in an electronic diary. Unscheduled health care utilization was determined by self-report. To account for over-the-counter antipyretic, analgesic medications that might have been used during the run-in phase before randomization, outcome data from the first 2 weeks after randomization were not included in the analysis.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

In the analysis of the primary outcome, we compared the two treatment groups with respect to the frequency of asthma exacerbations using a log-linear model in which the number of exacerbations was assumed to follow a negative binomial distribution. Because the number of observed exacerbations would be expected to depend on the length of time a participant remained in the study, the model included an offset for each participant that represented the amount of time the participant was actually followed in the study. The use of the offset standardized the number of exacerbations to a common period so that the results could be presented as rates of exacerbation and the treatments could be compared by calculation of a relative rate.12 Because data from participants who dropped out during the first 2 weeks could not be used, the primary analysis included all participants who completed at least 2 weeks of follow-up. To assess the potential effect of dropout on the study results, we performed an additional analysis of the primary outcome that included only data from participants who completed the entire follow-up, an analysis that included only data from participants who completed the entire follow-up and who used at least one dose of trial medication, and sensitivity analyses that were based on the imputation of missing data under three difference scenarios.

Among the prespecified secondary outcomes, the frequency of unscheduled health care utilization was analyzed in the same way as the analysis of the primary outcome; we calculated asthma-control days and albuterol use by averaging the data that were entered in the electronic diary over the follow-up period, with the exclusion of the first 2 weeks, and then analyzed the data as continuous variables using standard analysis of variance models. All analyses included clinical site and treatment sequence in the INFANT trial as covariates. In prespecified secondary analyses, we examined the potential dose–response relationship by including the total number of trial medication doses as a covariate in the models. Interactions between the antipyretic, analgesic medications used in the AVICA trial and the asthma medications used in the INFANT trial were examined as specified in the protocol.

Assuming an overall exacerbation rate of 0.97 per year and a dropout rate of 25%, we projected that a sample size of 294 participants would give the study 90% power to detect a relative rate of asthma exacerbation in the acetaminophen group as compared with ibuprofen group of 1.54, at a significance level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS

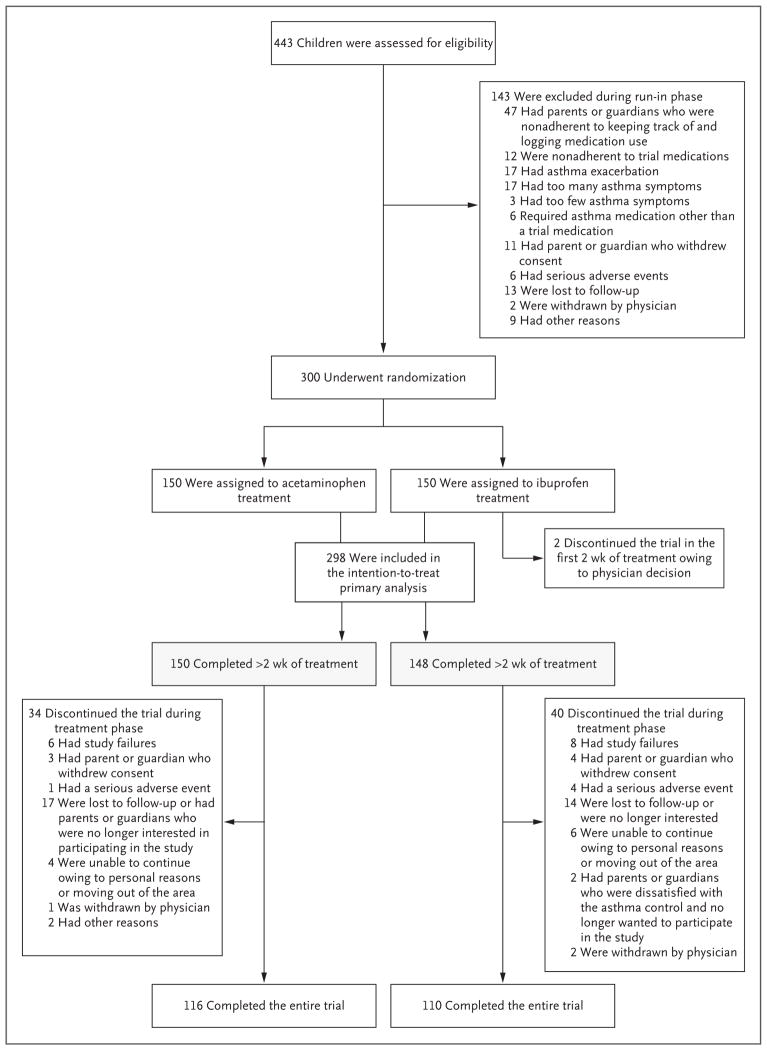

Of the 443 participants enrolled in the run-in phase of the study, 300 underwent randomization; 150 were assigned to the acetaminophen group and 150 to the ibuprofen group. A total of 226 participants (75.3%) completed the trial; there was no significant difference in the rate of attrition between the treatment groups (Fig. 1). Two participants withdrew from the ibuprofen group during the first 2 weeks of follow-up without having had an exacerbation and were not included in the analyses.

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, and Follow-up.

“Study failure” was defined as asthma that was not controlled well enough (prespecified criteria are listed in the protocol) for the child to remain in the study.

No significant between-group differences in baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were observed (Table 1). The mean (±SD) age at enrollment was 39.9±13.2 months. Participants reported a mean of 5.9±5.0 wheezing episodes in the year before entering the study, along with 3.0±2.4 urgent care or emergency department visits and 0.3±0.5 hospitalizations for wheezing. A total of 74.7% of the patients had received at least one oral glucocorticoid course for wheezing in the 12 months before entering the study; in the previous 6 months, participants received a mean of 1.1±1.1 courses of an oral glucocorticoid.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Participants.*

| Variable | Acetaminophen (N = 150) | Ibuprofen (N = 150) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristic | ||

| Age — mo | 40.3±12.9 | 39.4±13.6 |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 86 (57) | 93 (62) |

| Race or ethnic group — no. (%)† | ||

| White | 74 (49) | 74 (49) |

| Black | 47 (31) | 50 (33) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 35 (23) | 37 (25) |

| Age at onset of asthma — mo | 13.1±9.4 | 13.1±10.9 |

| Parent with history of asthma — no. (%) | 87 (58) | 91 (61) |

| Asthma measure at time of randomization | ||

| Oral glucocorticoid courses in the previous 6 months — no. | 1.01±1.06 | 1.15±1.04 |

| Urgent care or emergency department visits in the previous year — no. | 3.13±2.45 | 2.96±2.29 |

| Hospitalizations in the previous year — no. | 0.29±0.57 | 0.26±0.51 |

| Percentage of asthma-control days‡ | 85.5±18.7 | 85.6±16.2 |

| Albuterol inhalations per week — no. | 1.81±3.49 | 1.50±2.22 |

| Use of inhaled glucocorticoids in the previous 12 months — no. of patients (%) | 92 (61) | 86 (57) |

| Use of leukotriene receptor antagonist in the previous 12 months — no. of patients (%) | 22 (15) | 39 (26) |

| Measure of atopy at time of randomization | ||

| Median IgE (interquartile range) — kU/liter | 64 (19–176) | 70 (24–252) |

| Median blood absolute eosinophil count (interquartile range) — cells/mm3 | 259.6 (172.5–524.8) | 248.4 (132.8–450.0) |

| Positive aeroallergen test — no. of patients (%) | 64 (43) | 62 (41) |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups in the characteristics listed.

Race or ethnic group was self-reported.

Asthma-control days were defined as full calendar days without the use of rescue medications for asthma, daytime asthma symptoms, nocturnal asthma symptoms, and unscheduled health care visits for asthma.

PRIMARY OUTCOME

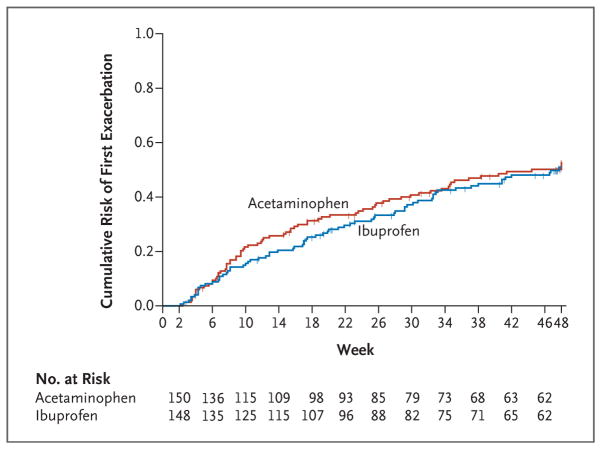

The children in the acetaminophen group had a mean of 0.81 asthma exacerbations (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65 to 1.02) over 46 weeks of follow-up, and children in the ibuprofen group had a mean of 0.87 exacerbations (95% CI, 0.69 to 1.10) (relative rate with acetaminophen vs. ibuprofen, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.28; P = 0.67) (Table 2). The rate of exacerbations also did not differ significantly between the groups when determined only among the 226 participants who completed the entire trial (relative rate, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.75 to 1.45; P = 0.79) (Table 2) or when determined only among the 200 participants who completed the entire trial and received a trial medication for pain or fever at least once (relative rate, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.68 to 1.32; P = 0.76) (Table 2). Although the dropout rate was similar in the two groups (27% in the ibuprofen group and 23% in the acetaminophen group), the difference in the dropout rate has some effect on the results. To examine the potential effect of dropout and the associated loss of information on the estimation of the relative risk and the associated 95% confidence interval, we performed sensitivity analyses that were based on the imputation of missing data under three different scenarios regarding exacerbations that might have been observed if there had been no dropout (i.e., maximum loss of information, minimum loss of information, and random loss of information). The results of these sensitivity analyses supported the results of the analysis of the primary outcome: estimates of the relative rate under the three scenarios ranged from 0.95 to 1.00, with a high degree of overlap across confidence intervals (see Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). In addition, there was no significant difference between the treatment groups in the time to first exacerbation (P = 0.70) (Fig. 2). Finally, no interaction was detected between asthma-controller therapy and treatment group (P = 0.91).

Table 2.

Asthma Outcomes.*

| Outcome | Acetaminophen (N = 150) | Ibuprofen (N = 150) | Relative Rate (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of asthma exacerbations that led to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids: primary outcome — no. of participants (%)† | ||||

| 0 | 76 (51) | 78 (53) | — | — |

| 1 | 42 (28) | 34 (23) | — | — |

| 2 | 16 (11) | 21 (14) | — | — |

| ≥3 | 16 (11) | 15 (10) | — | — |

| Mean exacerbation frequency over 46 weeks (95% CI) | ||||

| Among 298 total participants† | 0.81 (0.65 to 1.02) | 0.87 (0.69 to 1.10) | 0.94 (0.69 to 1.28) | 0.67 |

| Among 226 participants who completed the trial | 0.74 (0.58 to 0.93) | 0.70 (0.55 to 0.90) | 1.05 (0.75 to 1.45) | 0.79 |

| Among 200 participants who completed the trial and used at least one dose of trial medication | 0.74 (0.58 to 0.94) | 0.77 (0.60 to 1.00) | 0.95 (0.68 to 1.32) | 0.76 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Mean percentage of asthma-control days (95% CI) | 85.8 (83.7 to 87.8) | 86.8 (84.6 to 88.9) | −1.01 (−3.94 to 1.92)‡ | 0.50 |

| Mean no. of albuterol rescue inhalations per week (95% CI) | 2.8 (2.3 to 3.3) | 3.0 (2.4 to 3.6) | −0.2 (−0.9 to 0.6)‡ | 0.69 |

| Frequency of health care utilization over 46 weeks (95% CI)§ | 0.75 (0.60 to 0.95) | 0.76 (0.60 to 0.97) | 0.99 (0.72 to 1.37) | 0.94 |

CI denotes confidence interval.

Two participants (1%) dropped out of the ibuprofen group during the first 2 weeks without having had an exacerbation and were not included in the primary analysis.

This value is a mean difference (95% CI), rather than a relative rate.

Health care utilization included urgent care and emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

Figure 2. Time to First Asthma Exacerbation.

Shown are Kaplan–Meier curves for the cumulative risk of an asthma exacerbation during the course of the trial. In a Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis, no significant difference was seen between the treatment groups (P = 0.70). Tick marks indicate times at which data were censored owing to end of follow-up or dropout.

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

No significant between-group differences were detected with respect to asthma-control days (85.8% in the acetaminophen group and 86.8% in the ibuprofen group, P = 0.50), use of rescue albuterol (2.8 and 3.0 inhalations per week, respectively; P = 0.69), and unscheduled health care utilization for asthma (0.75 and 0.76 episodes per participant over 46 weeks of follow-up, P = 0.94) (Table 2).

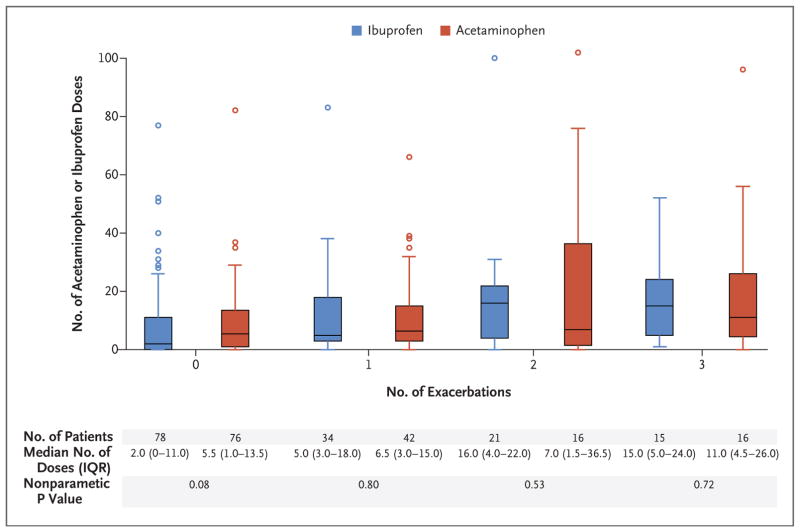

TRIAL MEDICATION USE AND ADHERENCE

The children in the acetaminophen group received a median of 7.0 doses (interquartile range, 2.0 to 15.0) of trial medication, and the children in the ibuprofen group received a median of 4.5 doses (interquartile range, 1.0 to 17.0) (P = 0.47 by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test). In total, participants received a median of 5.5 doses (interquartile range, 1.0 to 15.0). A total of 240 participants (80.0%) used the trial medication at least once during the study (124 [82.6%] in the acetaminophen group and 116 [77.3%] in the ibuprofen group). Figure 3 shows the wide variability of trial medication use and indicates that use of antipyretic, analgesic medications was significantly associated with the number of asthma exacerbations that led to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids (P<0.001 by the Kruskal–Wallis test). However, within each stratum of the number of exacerbations, no significant differences were observed between the acetaminophen group and the ibuprofen group.

Figure 3. Number of Doses of Acetaminophen or Ibuprofen, According to the Number of Asthma Exacerbations That Led to Treatment with Systemic Glucocorticoids.

Shown is the number of acetaminophen or ibuprofen doses that were administered in a blinded manner during the trial period, stratified according to the number of exacerbations that led to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids during the same period. P values for the comparison of treatments within each systemic glucocorticoid subgroup are based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The horizontal lines in the boxes represent the median number of doses of trial medication (acetaminophen or ibuprofen); the top and bottom edges of the boxes represent the the first and third quartiles; the I bars extend to the lowest and highest data value that is not more than 1.5 times the interquartile range below and above the lower and upper end of the box, respectively, and the circles are individual data points that are more than 1.5 times the interquartile range above the top edges of the box.

The use of open-label acetaminophen and ibuprofen represented a minority of exposures to antipyretic, analgesic medication. In the acetaminophen group, a total of 2261 doses of antipyretic, analgesic medication were administered to the participants, of which 1933 (85.5%) were doses of acetaminophen administered in a blinded manner, 137 (6.1%) were doses of open-label acetaminophen, and 191 (8.4%) were doses of open-label ibuprofen. In the ibuprofen group, a total of 1934 doses of antipyretic–analgesic medication were administered, of which 1731 (89.5%) were doses of ibuprofen administered in a blinded manner, 110 (5.7%) were doses of open-label acetaminophen, and 93 (4.8%) were doses of open-label ibuprofen.

ADVERSE EVENTS

No significant between-group differences were observed with respect to adverse events or serious adverse events (Tables S2 and S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). Six serious adverse events occurred in the acetaminophen group and 12 in the ibuprofen group. No deaths from any cause occurred during the trial.

DISCUSSION

This prospective, randomized, double-blind trial examined whether the standard, as-needed use of acetaminophen was associated with a higher risk of asthma exacerbation or with worse asthma control than was the standard, as-needed use of ibuprofen in young children with mild persistent asthma. The results showed no significant difference in the frequency of asthma exacerbations or in asthma control between the two treatment groups.

The potential association between the use of acetaminophen and asthma-related complications (i.e., exacerbations, daily symptoms, and need for bronchodilators) has been a matter of considerable debate. Although several observational studies have shown an association between impaired asthma control and the use of acetaminophen for symptom relief in children and adults,2–6 other studies have suggested that the association may have been confounded by indication: children with asthma have more symptomatic respiratory tract infections, during which time acetaminophen is often used for fever and malaise.9,13 As shown in Figure 3, we observed that greater use of antipyretic, analgesic medications was associated with more apparent respiratory illnesses and that the reported respiratory illnesses were associated with asthma exacerbations that led to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids. However, we found no evidence that acetaminophen, when used during periods of respiratory illness, was associated with a higher risk of asthma exacerbations or other asthma-related complications than was ibuprofen.

Our findings are in contrast to those of a post hoc analysis of a randomized trial by Lesko et al.7 that showed that the relative risk of unscheduled visits for asthma was substantially higher in the weeks after taking acetaminophen for febrile illness than in the weeks after taking ibuprofen (relative risk, 1.79). As opposed to a post hoc analysis, our study was specifically designed and intended to prospectively evaluate the effect of the use of acetaminophen versus ibuprofen in carefully screened children with persistent asthma. Other studies have shown no effect of acetaminophen, as compared with placebo, on asthma outcomes when given during periods during which the participants were healthy,14,15 but this use of acetaminophen is inconsistent with the use in clinical practice. Our study investigated the “real-world” use of acetaminophen or ibuprofen as needed for pain and fever, which often coincide with viral respiratory tract infections in this age group. As shown in Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix, the rate of acetaminophen use in our trial was similar to the rates noted in observational studies that evaluated the effect of acetaminophen use on asthma outcomes.5,9 For example, 70 of the 150 participants (46.7%) in the acetaminophen group in the current trial received more than 10 doses of acetaminophen per year. By comparison, Sordillo et al.9 reported that 42% of participants were given more than 10 doses of acetaminophen in their first year of life, and Wickens et al.5 reported that 37% of participants 5 to 6 years of age were given more than 10 doses of acetaminophen per year.

Several limitations of this trial should be noted. First, our trial enrolled young children who had mild persistent asthma and who were receiving treatment with asthma-controller therapy; the results may not be generalizable to other age groups or to patients who have more severe asthma that requires treatment with a higher level of asthma-controller medications. Second, we did not find an interaction effect between the asthma-controller therapy and the analgesic, antipyretic medication used (i.e., the rates of asthma exacerbations did not differ significantly when acetaminophen was compared with ibuprofen in each group of participants receiving one of three asthma-controller regimens in the INFANT trial). However, it should be noted that adherence to asthma-controller medications among the participants in the current trial was closely monitored. Therefore, the results of our trial may not be applicable to children who do not adhere to their controller therapies or to children who live in countries in which leukotriene-receptor antagonists are not commonly used as monotherapy for mild persistent asthma. Third, our findings do not answer the question of whether prenatal exposure to acetaminophen or exposure to acetaminophen during the first year of life is associated with the development of asthma, as suggested in other studies.2,16,17 Finally, although the rates of exacerbation that we observed in the two treatment groups were numerically similar, our results do not show with certainty that they are equal. This uncertainty is reflected in the confidence interval for the relative rate, which extends from 0.69 to 1.28; therefore, our data do not exclude the possibility that the use of acetaminophen could be associated with up to a 28% higher or a 31% lower relative risk of asthma exacerbations.

We excluded a placebo group for ethical reasons, since giving placebo to a child with fever, malaise, and pain would not be acceptable. Without a placebo group, we cannot exclude the possibility that both ibuprofen use and acetaminophen use may be associated with parallel increases in either asthma exacerbations or symptoms. However, ibuprofen and acetaminophen have different mechanisms of action. It is thus highly unlikely that their use could be associated with similar increases in the rate of asthma-related complications (i.e., exacerbations, daily symptoms, and use of bronchodilators) that are known to be determined by disparate mechanisms of disease. Regardless, the focus of our trial was not to compare these medications with placebo with respect to asthma outcomes. Instead, the focus of our study was to answer the important practical question from clinicians and parents regarding which medication to use, acetaminophen or ibuprofen, when children with asthma are having fever, pain, or discomfort that necessitates treatment with an antipyretic, analgesic medication.

In conclusion, over the 1-year study period, we did not find that asthma exacerbations or other markers of asthma-related complications occurred more frequently among children who were randomly assigned to receive acetaminophen than among those who were randomly assigned to receive ibuprofen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) including HL098102, HL098096, HL098075, HL098090, HL098177, HL098098, HL098107, HL098112, HL098103, HL098115, TR001082, TR000439, TR000448, TR000454, K23AI104780, and K24AI106822. AsthmaNet is a clinical trials network supported by a cooperative agreement with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Dr. Mauger reports receiving study drug medications from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Teva, and Sunovion for use in clinical trials; Dr. Paul, receiving fees for serving on advisory boards from Pfizer, McNeil Consumer Healthcare, the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, Perrigo Nutritionals, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Procter & Gamble and consulting fees from the Consumer Healthcare Products Association and Procter & Gamble; Dr. Szefler, receiving fees for serving on a steering committee from GlaxoSmithKline, fees for serving on advisory boards from Genentech, consulting fees from Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, Novartis, Roche, AstraZeneca, and Aerocrine, and grant support from GlaxoSmithKline; Dr. Fitzpatrick, receiving fees for serving on advisory boards from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Boehringer Ingelheim and consulting fees from Genentech; Dr. Jackson, receiving consulting fees from Vectura and grant support from GlaxoSmithKline; Dr. Bacharier, receiving fees for serving on advisory boards from Merck, Sanofi, and Vectura, fees for serving on a data and safety monitoring board from DBV Technologies, consulting fees from Aerocrine, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech/Novartis, Schering, Cephalon, Teva, and Boehringer Ingelheim, lecture fees from Aerocrine, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech/Novartis, Merck, Teva, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca, and honoraria for continuing medical education (CME) program development from WebMD/Medscape; Dr. Cabana, receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from the Merck Childhood Asthma Network and lecture fees from Merck; Dr. Lemanske, receiving consulting fees from Merck, Sepracor, SA Boney and Associates, GlaxoSmithKline, the American Institute of Research, Genentech, Double Helix Development, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Health Star Communications, lecture fees from Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, and grant support from Pharmaxis; Dr. Martinez, receiving grant support from Johnson & Johnson; Dr. Chmiel, receiving fees for serving on advisory boards from Boehringer Ingelheim and Gilead Sciences, consulting fees from Nivalis Therapeutics and Celtaxsys, and grant support from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Teva, Roche, Vertex, Grifols, Nivalis Therapeutics, Insmed, Corbus, KaloBios, and N30 Pharmaceuticals; Dr. Gentile, receiving fees for serving on advisory boards from Greer and Mylan and lecture fees from Merck and Greer; Dr. Israel, receiving fees for serving on data and safety monitoring boards for Novartis, consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Philips Respironics, Regeneron, Teva, and Cowen and Company, fees from law firms for providing expert testimony related to illness on behalf of patients, study drug medication from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Sunovion, and Teva for use in clinical trials, travel support from Research in Real Life (RiRL) and Teva, and grant support from Genentech; Dr. Lazarus, receiving fees for serving as a speaker and judge at the Respiratory Disease Young Investigators’ Research Forum, a CME event supported in part by an educational grant from AstraZeneca; Dr. Ly, receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Gilead Sciences, fees for a presentation on asthma adherence from Genentech, and that she is codeveloping a mobile spirometer and mobile app with Knox Medical Diagnostics; Dr. Morgan, receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Genentech; Dr. Peters, receiving fees for serving on advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Aerocrine, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Sunovion, and Teva, fees for serving on a data and safety monitoring committee from Gilead Sciences, consulting fees from Array Biopharma, Experts in Asthma, Ono Pharmaceuticals, PPD Development, Saatchi & Saatchi, Targacept, Teva, and Theron, fees for CME program presentations from Integrity CE, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Quintiles, and grant support from Novartis; Dr. Ross, receiving study drug medication from Sunovion, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Teva, and GlaxoSmithKline for use in clinical trials and grant support from Teva, AstraZeneca, Roche, and Novartis; Dr. Wechsler, receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Teva, consulting fees from Sepracor/Sunovion, NKT Therapeutics, Asthmatx/BSCI, Merck, Regeneron, MedImmune, Ambitbio, Vectura, Sanofi, Teva, Mylan, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Meda, Theravance, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Tunitas, and Gliacure, honoraria from Asthmatx/BSCI and Merck, and lecture fees from Merck. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

We thank William W. Busse, M.D. (chair of the AsthmaNet steering committee); the project scientists from NHLBI, including Robert Smith, Ph.D., and Virginia Taggart, M.P.H.; the study participants; the investigators, study coordinators, and staff at the AsthmaNet clinical research centers; the physicians at the Pediatric Physicians’ Organization at Boston Children’s Hospital for assistance with participant recruitment; the personnel at the data coordinating center; and others who provided assistance in the recruitment of the study participants or other assistance in the implementation of the study (a list of the additional contributors is provided in the Supplementary Appendix).

APPENDIX

The authors’ full names and academic degrees are as follows: William J. Sheehan, M.D., David T. Mauger, Ph.D., Ian M. Paul, M.D., James N. Moy, M.D., Susan J. Boehmer, M.A., Stanley J. Szefler, M.D., Anne M. Fitzpatrick, Ph.D., Daniel J. Jackson, M.D., Leonard B. Bacharier, M.D., Michael D. Cabana, M.D., Ronina Covar, M.D., Fernando Holguin, M.D., Robert F. Lemanske Jr., M.D., Fernando D. Martinez, M.D., Jacqueline A. Pongracic, M.D., Avraham Beigelman, M.D., Sachin N. Baxi, M.D., Mindy Benson, M.S.N., P.N.P., Kathryn Blake, Pharm.D., James F. Chmiel, M.D., Cori L. Daines, M.D., Michael O. Daines, M.D., Jonathan M. Gaffin, M.D., Deborah A. Gentile, M.D., W. Adam Gower, M.D., Elliot Israel, M.D., Harsha V. Kumar, M.D., Jason E. Lang, M.D., M.P.H., Stephen C. Lazarus, M.D., John J. Lima, Pharm.D., Ngoc Ly, M.D., Jyothi Marbin, M.D., Wayne J. Morgan, M.D., Ross E. Myers, M.D., J. Tod Olin, M.D., Stephen P. Peters, M.D., Ph.D., Hengameh H. Raissy, Pharm.D., Rachel G. Robison, M.D., Kristie Ross, M.D., Christine A. Sorkness, Pharm.D., Shannon M. Thyne, M.D., Michael E. Wechsler, M.D., and Wanda Phipatanakul, M.D.

The authors’ affiliations are as follows: the Divisions of Allergy and Immunology (W.J.S., S.N.B., W.P.) and Respiratory Diseases (J.M.G.), Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and the Division of Allergy and Pulmonary Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School (E.I.) — all in Boston; the Departments of Public Health Sciences (D.T.M., S.J.B.) and Pediatrics (I.M.P.), Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, and the University of Pittsburgh Asthma Institute at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (F.H.) and the Department of Pediatrics, Allegheny General Hospital (D.A.G.), Pittsburgh — all in Pennsylvania; Stroger Hospital of Cook County and Department of Pediatrics, Rush University Medical Center (J.N.M.), Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago (J.A.P., R.G.R.), and University of Illinois at Chicago (H.V.K.) — all in Chicago; the Breathing Institute, Children’s Hospital Colorado (S.J.S.), and the Departments of Pediatrics (S.J.S.) and Medicine (M.E.W.), University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, and the Department of Pediatrics (R.C., J.T.O.) and Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine (M.E.W.), National Jewish Health, Denver — both in Colorado; the Department of Pediatrics, Emory University, Atlanta (A.M.F.); the Section of Allergy, Immunology, and Rheumatology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health (D.J.J., R.F.L.) and the School of Pharmacy, University of Wisconsin–Madison (C.A.S.) — both in Madison; Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the Department of Pediatrics, St. Louis Children’s Hospital (L.B.B., A.B.) — both in St. Louis; the Departments of Pediatrics (M.D.C.) and Medicine (S.C.L.) and the Airway Clinical Research Center (N.L.), University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, Oakland (M.B., J.M.), and Olive View UCLA Medical Center and Department of Pediatrics, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles (S.M.T.) — all in California; Arizona Respiratory Center, University of Arizona, Tucson (F.D.M., C.L.D., M.O.D., W.J.M.); Nemours Children’s Health System, Jacksonville (K.B., J.J.L.), and Nemours Children’s Hospital, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, Orlando (J.E.L.) — both in Florida; Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital and Department of Pediatrics, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland (J.F.C., R.E.M., K.R.); Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC (W.A.G., S.P.P); and the Division of Pulmonology, Department of Pediatrics, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque (H.H.R.).

Footnotes

The authors’ full names, academic degrees, and affiliations are listed in the Appendix.

References

- 1.Vernacchio L, Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Mitchell AA. Medication use among children <12 years of age in the United States: results from the Slone Survey. Pediatrics. 2009;124:446–54. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beasley R, Clayton T, Crane J, et al. Association between paracetamol use in infancy and childhood, and risk of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in children aged 6–7 years: analysis from Phase Three of the ISAAC programme. Lancet. 2008;372:1039–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beasley RW, Clayton TO, Crane J, et al. Acetaminophen use and risk of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in adolescents: International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase Three. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:171–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201005-0757OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davey G, Berhane Y, Duncan P, Aref-Adib G, Britton J, Venn A. Use of acetaminophen and the risk of self-reported allergic symptoms and skin sensitization in Butajira, Ethiopia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:863–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wickens K, Beasley R, Town I, et al. The effects of early and late paracetamol exposure on asthma and atopy: a birth cohort. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKeever TM, Lewis SA, Smit HA, Burney P, Britton JR, Cassano PA. The association of acetaminophen, aspirin, and ibuprofen with respiratory disease and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:966–71. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1269OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lesko SM, Louik C, Vezina RM, Mitchell AA. Asthma morbidity after the short-term use of ibuprofen in children. Pediatrics. 2002;109(2):E20. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBride JT. The association of acetaminophen and asthma prevalence and severity. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1181–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sordillo JE, Scirica CV, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Prenatal and infant exposure to acetaminophen and ibuprofen and the risk for wheeze and asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma — summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(Suppl):S94–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan JE, Farrar HC Section on Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Committee on Drugs. Fever and antipyretic use in children. Pediatrics. 2011;127:580–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilbe J. Negative binomial regression. 2. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnabel E, Heinrich J. Respiratory tract infections and not paracetamol medication during infancy are associated with asthma development in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1071–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ioannides SJ, Williams M, Jefferies S, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled study of the effect of paracetamol on asthma severity in adults. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004324. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soferman R, Tsivion A, Farber M, Sivan Y. The effect of a single dose of acetaminophen on airways response in children with asthma. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2013;52:42–8. doi: 10.1177/0009922812462764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaheen SO, Newson RB, Henderson AJ, et al. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and risk of asthma and elevated immunoglobulin E in childhood. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perzanowski MS, Miller RL, Tang D, et al. Prenatal acetaminophen exposure and risk of wheeze at age 5 years in an urban low-income cohort. Thorax. 2010;65:118–23. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.121459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.