Abstract

Objective:

In this study, we aimed to uncover distinct antecedents of autobiographic memory dysfunction in patients with epilepsy with early (childhood/adolescence) vs late (adulthood) disease onset.

Methods:

One hundred sixty-six adults participated: 92 patients with focal epilepsy, whose cognitive and psychiatric functioning were compared to that of 74 healthy controls. Predictors of autobiographic memory deficit were contrasted between patients with early-onset (n = 47) vs late-onset (n = 45) epilepsy.

Results:

Overall, people with epilepsy performed significantly worse on measures of both semantic and episodic autobiographic memory and showed markedly high rates of depressive symptoms and disorders (p < 0.001). Reduced autobiographic memory in patients with early-onset epilepsy was associated with young age at onset, more frequent seizures, and reduced working memory. In contrast, the difficulty that patients with late-onset epilepsy had in recalling autobiographic information was linked to depression and the presence of an MRI-identified lesion.

Conclusions:

This study reveals that memory deficits in people with focal epilepsy have differing antecedents depending on the timing of the disease onset. While neurobiological factors strongly underpin reduced autobiographic function in patients with early-onset epilepsy, psychological maladjustment gives rise to the impairments seen in patients with late-onset epilepsy. More broadly, these findings support the practice of subtyping patients according to distinct clinical characteristics to find individualized predictors of cognitive dysfunction.

Cognitive impairment is common among people with epilepsy, with autobiographic memory deficits particularly pervasive. Relative to healthy controls, patients with focal epilepsy perform poorly on tasks asking them to recall personally relevant information from across their lifetime.1,2 These marked deficits often occur in the context of only mild decrements on standard neuropsychological tests of verbal and visual memory,1 indicating that autobiographic impairments can be the most prominent cognitive feature.

Neurocognitive phenotyping of patients has the potential to provide more precise, individualized insights for management and treatment. There is growing evidence that the development of cognitive substrates may be disturbed by habitual seizures in childhood,3 providing a mechanism for memory decrement specific to childhood-onset epilepsy. In contrast, mechanisms underpinning autobiographic memory deficits that are specific to adult-onset epilepsies remain unclear. The elevated rate of depression in adults with epilepsy compared to those without the disease may offer one such mechanism,4 as impoverished autobiographic memory is robustly associated with depression.5

In this study, we examined whether the antecedents of memory deficits in people with epilepsy are influenced by the timing of disease onset. We hypothesized that impairments in individuals with seizures emerging in a critical neurodevelopmental period of childhood/adolescence will be linked to epilepsy-related factors; in contrast, reduced autobiographic recollection in recent-onset epilepsy will be linked to nonepilepsy factors such as depression.

METHODS

Participants.

A total of 166 adults participated in this prospective study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age 18 years or older, (2) Full Scale IQ (FSIQ) above the impaired range (i.e., >70), (3) neurosurgically naive, and (4) functional English. The patient sample comprised 92 individuals with focal epilepsy recruited consecutively via the Comprehensive Epilepsy Programme at Austin Health, Melbourne, between 2010 and 2015. Epileptogenic foci were identified by established methods from our group.6 The control sample comprised 74 individuals with no neurologic or psychiatric history largely recruited from the families of patients as a means of sociodemographic matching, with instructions given to avoid cross-contamination.

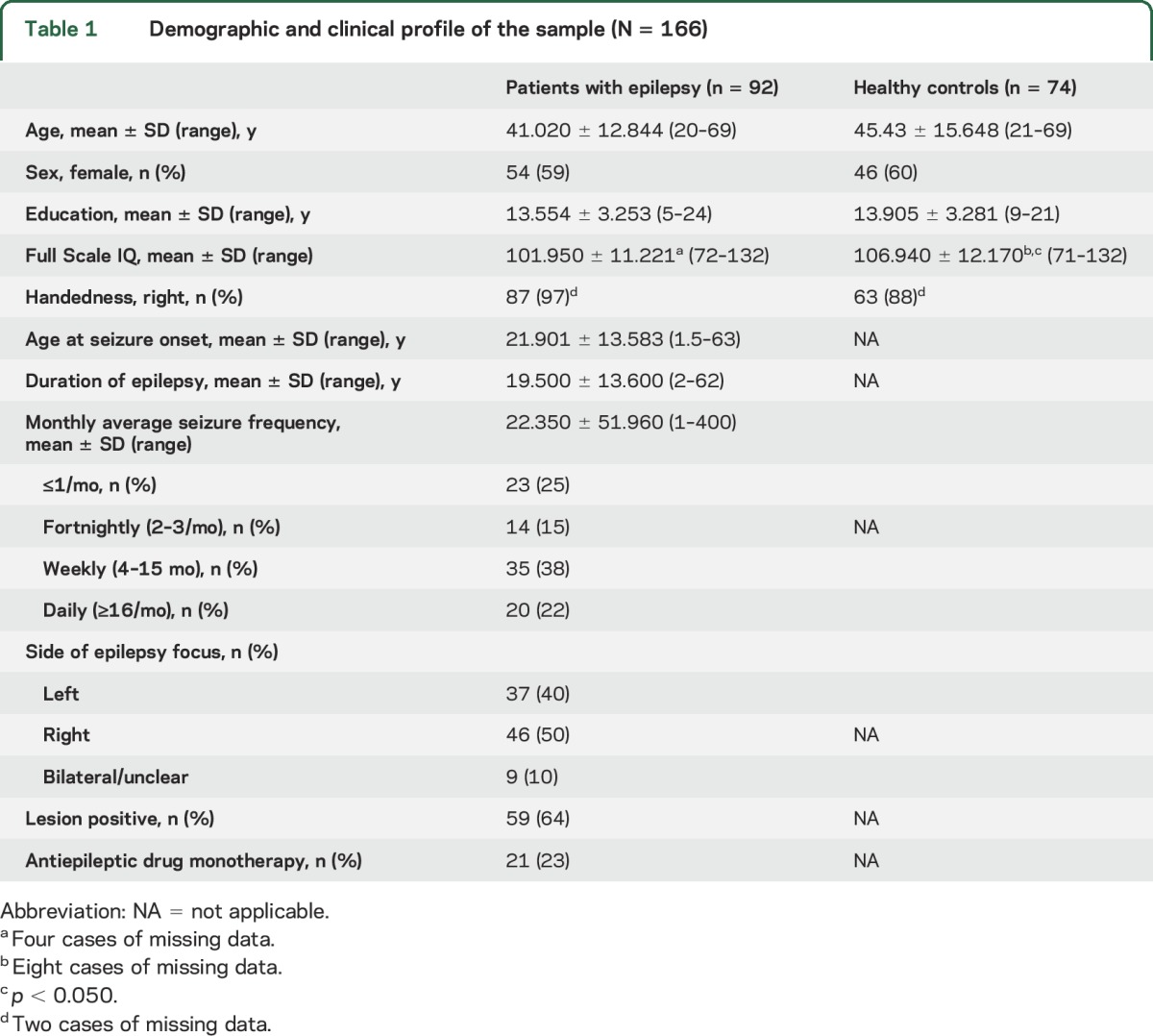

Demographic and medical information is outlined in table 1. Patients did not differ from controls in age, sex, or years of education (p > 0.050). The control sample had a slightly higher mean FSIQ than the patients (t152 = −2.631, p = 0.009, η2 = 0.043, small–medium effect size [ES]); however, mean scores for both groups fell within the average range (i.e., 90–110).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical profile of the sample (N = 166)

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The study was approved by the relevant human research ethics committees and all patients gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Neuropsychological evaluation.

Autobiographic memory.

The Autobiographical Memory Interview (AMI)7 is a semistructured interview assessing personal memories from childhood, early adulthood, and recent life. The Personal Semantic Schedule recalls personally relevant facts (e.g., classmates' names; maximum = 63). Scores ≤47 are associated with an amnestic syndrome and scores of 48 and 49 indicative of a probable amnestic syndrome. The Autobiographical Incident Schedule recalls 3 personal episodes from each time period (e.g., a wedding; maximum = 27), scored on their richness in detail and how precisely they are located in place and time; scores ≤12 are associated with an amnestic syndrome and 13 to 15 are indicative of probable amnestic syndrome.

Broader memory function.

We used the Wechsler Memory Scale–Fourth Edition8; specifically, auditory-verbal memory was assessed with immediate and delayed recall indices of the Verbal Paired Associates subtest, visual learning was assessed with the immediate and delayed indices of the Design Memory subtest, and working memory was assessed using the Symbol Span subtest. All subtests were scored according to age-scaled normative data (M = 10 ± 3).

Mood assessment.

Neuropsychiatric evaluation was performed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID), the gold standard measure for diagnosing mood disturbance according to the DSM. The Non-Patient Edition was used.9 The SCID allows for the diagnosis of subthreshold and atypical manifestations of depression that some researchers consider to be of especial interest to epilepsy, and ensures symptoms cannot be attributed to antiepileptic medication.

Complementing the SCID, the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E)10 was administered as a linear self-report measure of current depressive symptoms. Its 6 items are endorsed on a scale of 1 = never to 4 = always/often. NDDI-E scores >15 have been shown to have 90% specificity and 81% sensitivity for a diagnosis of depression in patients with epilepsy.

The PHQ–GAD-7 (Patient Health Questionnaire–Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item) was used to assess current anxiety symptoms.11 Participants assign scores of 0 to 3, to the responses “not at all”–“nearly every day,” respectively. Scores of 5, 10, and 15 represent cutpoints for mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively.

Statistical analyses.

Analyses were run using IBM SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) with statistical significance at p < 0.050 (2-tailed). Some data were missing because of interruptions by seizures or discharge so Little's MCAR (missing completely at random) test was used on a subset of cases and showed that there was no relationship between the missingness of data and any values (χ220 = 18.690, p > 0.050). A linear relationship between autobiographic memory indices and FSIQ in patients was assessed using scatterplots and Pearson product–moment correlations and rejected, negating any need to covary for FSIQ.

Predictors of impaired autobiographic recall in patients with onset in childhood/adolescence (“early onset”; n = 47) were contrasted to those of patients with onset in adulthood (“late onset”; n = 45). Definitions of developmental period were taken from World Health Organization criteria12: childhood = 0–8 years, adolescence = 9–19 years, adulthood ≥19 years. Each of the following analyses was run separately for patients with early- and late-onset epilepsy.

To identify variables likely to be predictors of autobiographic memory, bivariate Pearson product–moment correlations were calculated between AMI, Wechsler Memory Scale–Fourth Edition, mood, and seizure variables. This was done separately for the semantic and episodic indices of the AMI. Univariate analyses of variance or independent samples t tests were used to assess the strength of relationships between autobiographic memory scores and dichotomous variables such as history of depression.

Variables that were significantly associated with autobiographic memory function were then entered into hierarchical multiple regression equations to examine their comparative importance in predicting the semantic and episodic index scores from the AMI for each group, resulting in 4 regression models (early-onset semantic; early episodic; late semantic; late episodic).

RESULTS

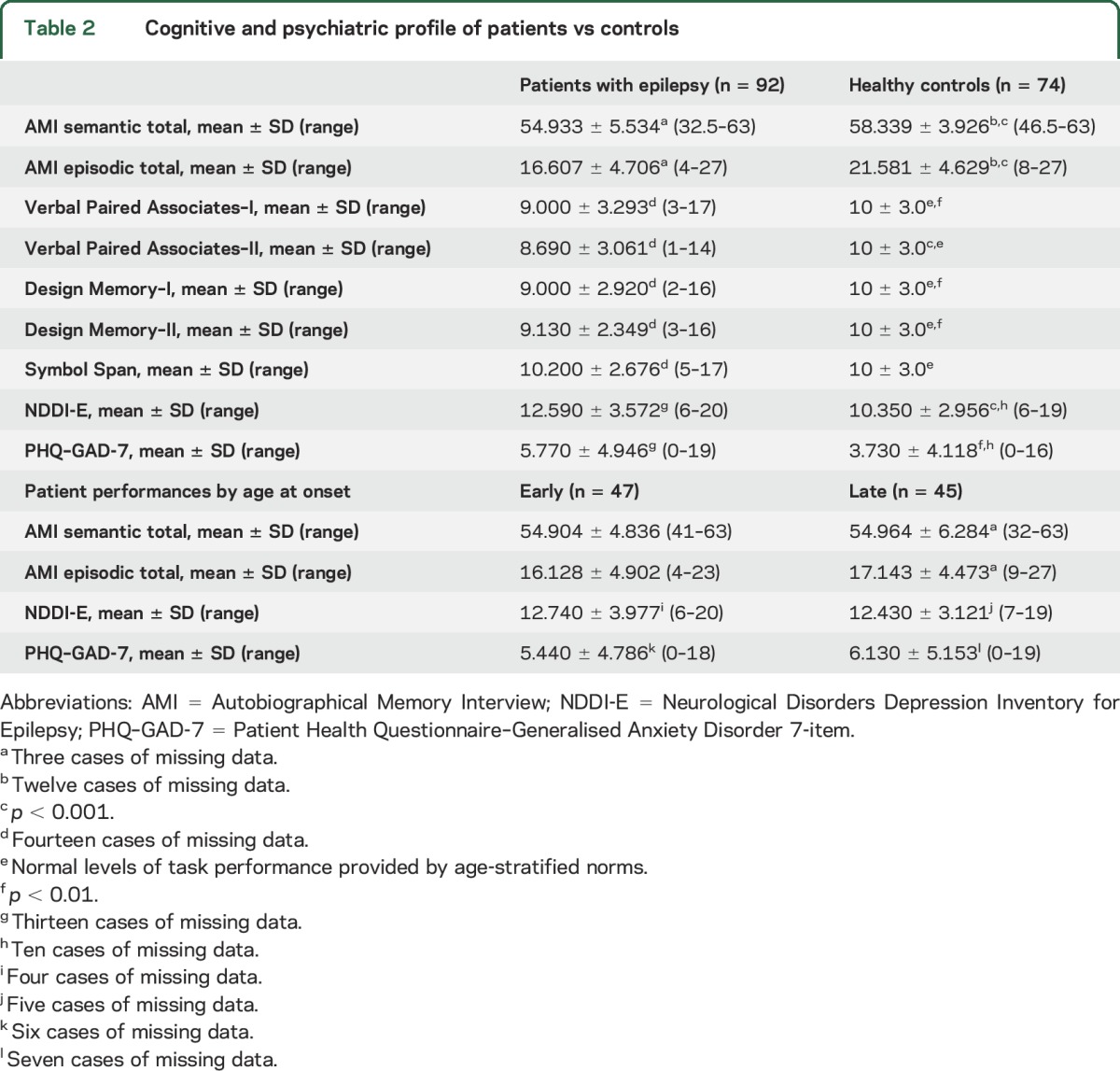

Overall, patients with epilepsy performed significantly worse on measures of both semantic and episodic autobiographic memory, as well as all indices of auditory-verbal and visual recall (table 2). Consistent with previous research, patients also had markedly high rates of depressive symptoms and disorder (p < 0.001). As they do not directly pertain to the hypotheses, a full description of these analyses is available in appendix e-1 at Neurology.org.

Table 2.

Cognitive and psychiatric profile of patients vs controls

Neurodevelopmental context of autobiographic memory predictors.

Correlates of autobiographic memory impairment in epilepsy were explored within the neurodevelopmental context of early vs late onset. Individuals with early onset (mean [M] current age = 37.470, SD = 12.729) were younger at testing than patients whose onset was in adulthood (M = 44.730, SD = 12.008; t90 = −2.813, p = 0.006, η2 = 0.081, medium–large ES), but had a longer duration of epilepsy (M = 26.130 years, SD = 14.178 vs M = 12.580, SD = 8.743; t77.081 = 5.543, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.254, very large ES). The 2 patient groups did not differ on any other clinical, neuropsychological, or psychiatric variables (p > 0.050), including autobiographic memory.

Autobiographic impairments in early-onset epilepsy relate to disease chronicity.

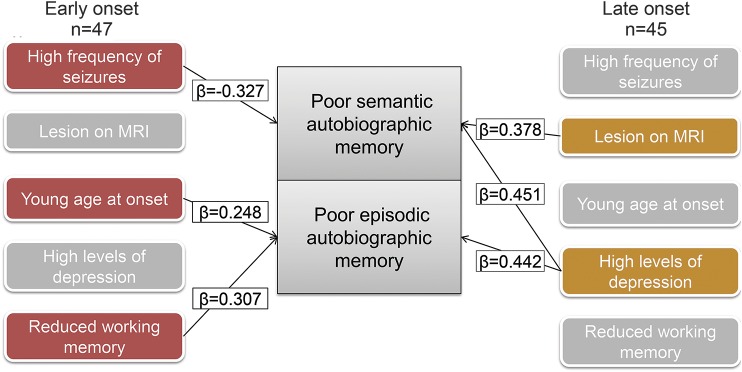

For patients with early-onset epilepsy, poor recall of personally relevant semantic facts was associated with a higher monthly average seizure frequency (r = −0.327, p = 0.012, medium ES). Multiple regression disclosed that seizure frequency accounted for 11% of the variance in predicting semantic memory impairment in early-onset epilepsy (F1,45 = 5.406, p = 0.025; adjusted R2 = 0.087; figure).

Figure. Determinants of poor autobiographic memory in epilepsy vary by age at onset.

Impaired autobiographic memory recall in patients with early onset in epilepsy is linked to indices of increased seizure chronicity and reduced working memory, while the impairment seen in patients with late-onset epilepsy is largely predicted by elevated symptoms of depression. β = standardized coefficient.

The poor recall of salient life events in people with early-onset epilepsy was found to be associated with younger age at the onset of seizures (r = 0.276, p = 0.032, medium-strength ES) and lower Symbol Span score (r = 0.330, p = 0.046, medium-strength ES). Adding Symbol Span and the age at onset sequentially to a hierarchical multiple regression established that, with only Symbol Span in the equation, the model accounted for 10.9% of the variance (F1,34 = 4.147, p = 0.050). Symbol Span and age at onset together, however, gave rise to a model that accounted for 17% of the variance (F2,33 = 3.369, p = 0.047, adjusted R2 = 0.119; see the figure).

Autobiographic impairments in late-onset epilepsy linked to depression.

In contrast, poor semantic memory in late-onset epilepsy was associated with higher depression scores on the NDDI-E (r = −0.393, p = 0.007, medium–large ES). Cognitive correlates included lower scaled scores for Designs-I immediate recall (r = 0.429, p = 0.006, medium–large ES), Designs-II delayed recall (r = 0.395, p = 0.011, medium ES), as well as Symbol Span (r = 0.316, p = 0.034, medium ES). Being lesion positive also resulted in poorer recall of semantic facts (mean = 53.537, SD = 7.014 vs lesion negative: mean = 57.533, SD = 3.647; t40 = −2.050, p = 0.047, η2 = 0.306, very large ES), as did medical polytherapy (mean = 53.742, SD = 6.689) rather than monotherapy (mean = 58.409, SD = 3.161; t40 = 2.215, p = 0.033, η2 = 0.109, large ES). Inspection of regression diagnostics suggested that the cognitive variables were collinear, and therefore on a priori theoretical grounds, only Symbol Span was retained; polytherapy was collinear with NDDI-E scores (polytherapy associated with lower depression scores), and polytherapy was excluded. R was significantly different from zero at the end of each step; however, Symbol Span did not add any unique variance and was omitted. With only NDDI-E scores in the equation, the model accounted for 15.4% of the variance (F1,36 = 6.561, p = 0.015, adjusted R2 = −0.13). Depressive symptoms and lesion status together, however, accounted for 29.4% of the variance (F2,35 = 7.270, p = 0.002, adjusted R2 = 0.25) indicating that a significant increment in R2 was gained by including lesion status as a predictor of semantic recall (specifically, p = 0.013; figure).

Poor recollection of episodic autobiographic memories in the late-onset group was also associated with higher NDDI-E scores (r = 0.442, p = 0.003, large ES). Cognitive correlates comprised reduced scaled scores for Verbal Paired Associates–I (r = 0.333, p = 0.031, medium ES), Verbal Paired Associates–II (r = 0.352, p = 0.024, medium–large ES), Designs-I (r = 0.303, p = 0.041, medium ES), Designs-II (r = 0.414, p = 0.008, medium–large ES), and Symbol Span (r = 0.309, p = 0.038, medium ES). Again, the cognitive variables were collinear and only Symbol Span was retained. R was significantly different from zero at the end of each step but Symbol Span did not add any unique variance and was omitted from the final model. Depression scores accounted for 19.5% of the variance in predicting episodic impairments in patients with late-onset epilepsy (F1,36 = 8.729, p = 0.005, adjusted R2 = −0.173; figure).

DISCUSSION

The findings of the current study indicate that the mechanisms of memory impairment differ among patients depending on the timing of their disease onset, implying that neurocognitive network functioning may be disrupted by distinct neurologic and psychological states at different points over the life span.

In patients whose seizures began as children or teenagers, impoverished autobiographic memory was associated with markers of disease chronicity: more frequent seizures and younger age at disease onset. The relationship between chronic seizures and dysfunction in cognitive networks is well described. EEG-fMRI demonstrates that cognition-related networks can be coactivated during epileptogenic discharges,13 including in childhood epilepsy,14 and over time alter their functioning and connectivity.15 The autobiographic memory network (AMN) links orbitomesial prefrontal cortex, rostral anterior cingulate, hippocampus, posterior cingulate, retrosplenial cortex, precuneus, and parietal regions.16 Compared to controls, people with epilepsy exhibit altered activation and connectivity throughout the AMN that is linked to longer duration of epilepsy,15 indicating that habitual seizures alter the function of this neurocognitive network over the long term.

Moreover, children with epilepsy have reduced neurocognitive reserve with which to resist the cumulative effects of neurologic disruption caused by regular seizures. Early onset is associated with abnormal anatomical neurodevelopment that is in turn linked to poor cognitive function,3 with cognitive vulnerability typically persisting across the life span.17 The emergence of persistent neurocognitive derangement around seizure onset lends support to the view that some cognitive and behavioral disturbances might be considered primary manifestations of epilepsy.18 In this way, the network disease that gave rise to seizures may have deranged or arrested the development of the AMN in childhood and resulted in personal experiences being less efficiently encoded from then on. Secondary contributing factors could also include medication side effects such as sedation, or “blanks” in life events due to seizures with altered awareness.

The key role of working memory in autobiographic retrieval is also evident in the early-onset group. Behavioral studies show that autobiographic recall relies on efficient working memory to select and retrieve personal memories in a goal-directed manner,19 processes mediated by the midline prefronto-cingulate cognitive control network.20 Working memory is frequently impaired in epilepsy,21 with secondary effects on the efficiency of autobiographic retrieval.22 Although the working memory scores in early- vs late-onset patients were equivocal, the unique contribution of poor working memory to poor autobiographic memory in early-onset patients may suggest that early seizures alter the cognitive control network in a way that uniquely undermines the efficient retrieval of autobiographic details.

In contrast, the autobiographic memory impairments evidenced by people with late-onset seizures were chiefly underpinned by depressive symptoms, suggesting that psychological maladjustment to seizures in adulthood takes a cognitive toll. This is commensurate with evidence that impoverished autobiographic retrieval is a robust feature of unipolar depression.5 Although problematic to tease out encoding vs retrieval deficits in the current design, the evidence from unipolar depression suggests that the autobiographic memory problem in adult-onset epilepsy may be a retrieval rather than encoding issue. This would implicate inferior prefrontal dysfunction in the AMN.19 Accordingly, epilepsy-specific research shows that the severity of depressive symptoms predicts the extent of memory dysfunction,23 with poor verbal elaboration of memories linked to abnormal ipsilateral frontotemporal function.24 One interpretation of these converging findings could be that co-occurring depression and memory impairments in epilepsy share a common network substrate that has been deranged by the disease, resulting in seizures as well as psychiatric and cognitive features.18 The AMN is a logical candidate.

Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the AMN is a characteristic neuroimaging feature of depression thought to give rise to cognitive symptoms of the disorder such as rumination and vague autobiographic recollections.5,25 Although speculative, the current findings may indicate that adult-onset patients engage overly introspective autobiographic processes as part of the cognitive reframing process we know is undertaken after diagnosis, as they struggle with pervasive feelings of loss of control and altered self-identity.26 This interpretation may also somewhat account for the finding that the late-onset group did not endorse higher rates of depressive symptoms than the early-onset group; rather, their depressive symptoms may have a more cognitive “flavor” that recruits the AMN, as is seen in recent research showing that a cognitive phenotype of depression predominates in epilepsy, especially in those with onset in adulthood (see appendix e-2).

The episodic memory impairment in late-onset epilepsy was also partially predicted by the presence of a lesion on MRI. Structural lesions carry an additive risk of cognitive dysfunction with cumulative effects on cognitive networks.27 Moreover, despite being epileptologically “dormant,” these lesions may have nonetheless skewed the maturation of cognitive networks important for autobiographic memory,28 perhaps suggesting that some adult-onset syndromes reflect an underlying disorder of neurocognitive development.

The striking implication of the current study is that the timing of disease onset determines the factors that underpin memory impairments in epilepsy. While it is hardly novel to suggest that seizures in childhood are “bad” for the developing brain, these data go further, suggesting that divergent clinical, behavioral, and cognitive features of epilepsy have fluctuating levels of influence over the functioning of cognitive networks, dependent on the stage of brain maturation. Cognition-related brain networks are revealed to be a dynamic system from which different streams of functioning can emerge.

For patients whose epilepsy presented in childhood or adolescence, the disease coincides with the progression of the brain from a clump of immature cells to a series of highly sophisticated networks.29 Seizures in this period can result in physiologic changes not seen in adult-onset epilepsies, such as aberrant sprouting in the hippocampus, reduced neurogenesis, and anomalous glutamate receptor distribution, with recurrent seizures likely deepening abnormalities over the long-term.29 Concordantly, the cognitive networks of patients with early onset seem to be built differently. For instance, cortical thickness measurements of young adults with resolved childhood absence epilepsy (n = 30) showed that relative to controls (n = 56), the disease had altered the development of an anterior cognitive network hub, with the downstream effect of slowing the later development of posterior networks30—evidence that early onset skews the normal development of neurocognitive networks into adulthood.

In contrast, once the main thrust of development has tapered off, the functioning of cognitive networks in patients with adult-onset seizures remains vulnerable to disruption from accompanying psychiatric disease or structural brain defects. Functional networks such as the AMN are best regarded as snapshots of constantly shifting neural activity,31 whereby static neuronal architecture and connections have the capability to flexibly reconfigure their connections in response to internal and external demands.31 Chronic network alteration, however, can arise in the context of persistent abnormal function associated with psychiatric disease or structural change.25

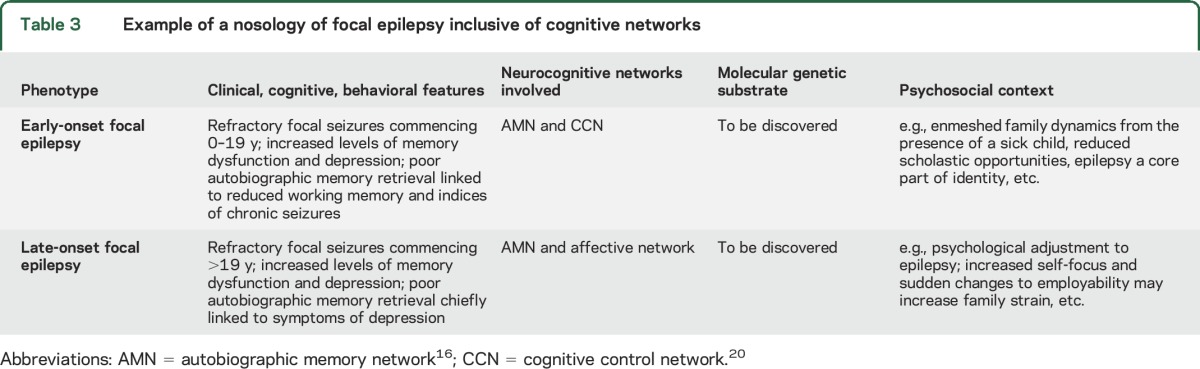

The current study highlights the clinical and research value of subtyping patients into more homogeneous phenotypes. Given that cognitive network systems are dynamic, any abnormal functioning has the potential to be reversible; this is consistent with meta-analytic evidence that hyperactivation of the AMN in unipolar depression normalizes once the disease is treated and in remission.32 Phenotyping makes this endeavor more precise.33 For instance, linking a phenotype of focal epilepsy that has a distinct cognitive network profile to polymorphisms in known genes could give clues as to which molecular pathways could be targeted in an etiologic treatment for that specific phenotype. One bold approach involves increasing the level of neurobiological detail in epilepsy classification criteria,34 aligning the signs and symptoms of epilepsy phenotypes to their environmental contexts, neuroimaging patterns, and molecular substrates (see table 3 for an example). This approach could make clinical practice more individually tailored, with consideration given to the significance of neurologic, cognitive, and neuropsychiatric features observed in the individual, including differential prognoses and treatment options.

Table 3.

Example of a nosology of focal epilepsy inclusive of cognitive networks

In conclusion, the results of this study support a life-span approach to understanding the cognitive impairments common to neurology, taking into account the deleterious effects of seizures on the developing brain, as well as psychological processes associated with adjusting to a chronic illness. Different predictors of AMN dysfunction in different epilepsy syndromes support the use of neurocognitive phenotyping as a valid method to generate more individualized neurologic research. Crucially, the close interrelation of cognition and behavior in epilepsy suggests that these functions may share neural substrates, and questions the utility of studying them as independent epiphenomena of epilepsy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank all of the patients and their family members who generously participated in this study for no other reason than to advance neurologic research and improve the quality of life of fellow patients. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the ongoing support of colleagues in the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences, as well as the Comprehensive Epilepsy Programmes of Austin Health and Melbourne Health, particularly the director of the CEP at Austin Health, Professor Sam Berkovic.

GLOSSARY

- AMI

Autobiographical Memory Interview

- AMN

autobiographic memory network

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition)

- ES

effect size

- FSIQ

Full Scale IQ

- NDDI-E

Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy

- SCID

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Editorial, page 1634

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Genevieve Rayner: participated sufficiently in the work to take responsibility for content as an author, including drafting/revising the manuscript for content including medical writing, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, as well as study coordination. Graeme Jackson: participated sufficiently in the work to take responsibility for content as an author, including revising the manuscript for content including medical writing, study concept, interpretation of data, as well as study supervision. Sarah Wilson: participated sufficiently in the work to take responsibility for content as an author, including revising the manuscript for content including medical writing, study concept and design, interpretation of data, as well as study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

The work of G.J. is supported by an NHMRC Program Grant (400121), an NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (527800), and by a Victorian Government Operational Infrastructure Support Grant.

DISCLOSURE

G. Rayner reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. G. Jackson is supported by an NHMRC Program Grant (400121), an NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (527800), and by the Victorian Government Operational Infrastructure Support Grant Scheme. S. Wilson reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herfurth K, Kasper B, Schwarz M, Stefan H, Pauli E. Autobiographical memory in temporal lobe epilepsy: role of hippocampal and temporal lateral structures. Epilepsy Behav 2010;19:365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rayner G, Jackson GD, Wilson SJ. Behavioral profiles in frontal lobe epilepsy: autobiographic memory versus mood impairment. Epilepsia 2015;56:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermann BP, Dabbs K, Becker T, et al. Brain development in children with new onset epilepsy: a prospective controlled cohort investigation. Epilepsia 2010;51:2038–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuller-Thomson E, Brennenstuhl S. The association between depression and epilepsy in a nationally representative sample. Epilepsia 2009;50:1051–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams JM. Capture and rumination, functional avoidance, and executive control (CaRFAX): three processes that underlie overgeneral memory. Cogn Emot 2006;20:548–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson GD, Berkovic SF, Tress BM, Kalnins RM, Fabinyi GC, Bladin PF. Hippocampal sclerosis can be reliably detected by magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology 1990;40:1869–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopelman MD, Wilson BA, Baddeley AD. The Autobiographical Memory Interview. Bury St. Edmunds, UK: Thames Valley Test Company; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale, 4th ed. San Antonio: Pearson Assessment; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP). New York: Biometrics Research, New York Psychiatric Institute; 2002. Available at: http://www.scid4.org/. Accessed September 5, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilliam FG, Barry JJ, Hermann BP, Meador KJ, Vahle V, Kanner AM. Rapid detection of major depression in epilepsy: a multicentre study. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Adolescent health. 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- 13.Pillay N, Archer JS, Badawy RAB, Flanagan DF, Berkovic SF, Jackson G. Networks underlying paroxysmal fast activity and slow spike and wave in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Neurology 2013;81:665–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berman R, Negishi M, Vestal M, et al. Simultaneous EEG, fMRI, and behavior in typical childhood absence seizures. Epilepsia 2010;51:2011–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao W, Zhang Z, Pan Z, et al. Default mode network abnormalities in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: a study combining fMRI and DTI. Hum Brain Mapp 2011;32:883–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim ASN. The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci 2009;21:489–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baxendale S, Heaney D, Thompson PJ, Duncan JS. Cognitive consequences of childhood-onset temporal lobe epilepsy across the adult lifespan. Neurology 2010;75:705–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson SJ, Baxendale S. The new approach to classification: rethinking cognition and behavior in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2014;41:307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldo JV, Shimamura AP. Frontal lobes and memory. In: Baddely AD, Kopelmann MD, Wilson BA, editors. The Handbook of Memory Disorders. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Essen DCV, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:9673–9678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stretton JI, Winston G, Sidhu M, et al. Neural correlates of working memory in temporal lobe epilepsy: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 2012;60:1696–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drane DL, Lee GP, Cech H, et al. Structured cueing on a semantic fluency task differentiates patients with temporal versus frontal lobe seizure onset. Epilepsy Behav 2006;9:339–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dulay MF, Schefft BK, Fargo JD, Privitera MD, Yeh H. Severity of depressive symptoms, hippocampal sclerosis, auditory memory, and side of seizure focus in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2004;5:522–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helmstaedter C, Sonntag-Dillender M, Hoppe C, Elger C. Depressed mood and memory impairment in temporal lobe epilepsy as a function lateralization and localization. Epilepsy Behav 2004;5:696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rayner G, Jackson G, Wilson S. Cognition-related brain networks underpin the symptoms of unipolar depression: evidence from a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;61:53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velissaris SL, Wilson SJ, Saling MM, Newton MR, Berkovic SF. The psychological impact of a newly diagnosed seizure: losing and restoring perceived control. Epilepsy Behav 2007;10:223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuerst D, Shah J, Kupsky WJ, et al. Volumetric MRI, pathological, and neuropsychological progression in hippocampal sclerosis. Neurology 2001;57:184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell B, Lin JJ, Seidenberg M, Hermann B. The neurobiology of cognitive disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol 2011;7:154–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ben-Ari Y, Holmes GL. Effects of seizures on developmental processes in the immature brain. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:1055–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curwood EK, Pedersen M, Carney PW, Berg AT, Abbott DF, Jackson GD. Abnormal fronto-temporal cortex in childhood absence epilepsy: a cortical thickness connectivity study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2015;2:456–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sporns O. The human connectome: a complex network. Ann NY Acad Sci 2011;1224:109–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaveau P, Jabourian M, Lemogne C, Guionnet S, Bergouignan L, Fossati P. Brain effects of antidepressants in major depression: a meta-analysis of emotional processing studies. J Affect Disord 2011;130:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berkovic SF, Jackson GD. “Idiopathic” no more! Abnormal interaction of large-scale brain networks in generalized epilepsy. Brain 2014;137:2400–2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:748–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.