Abstract

Patient: Male, 49

Final Diagnosis: T-lymphoid/myeloid bilineal blastic transformation of CML

Symptoms: Rapidly enlarging mass in left neck

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Biopsy of the left submandibular lymph nodes

Specialty: Hematology

Objective:

Rare co-existance of disease or pathology

Background:

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal myeloproliferative disorder characterized by the Philadelphia chromosome generated by the reciprocal translocation t(9: 22)(q34;q11). CML is usually diagnosed in the chronic phase. Blast crisis represents an advanced phase of CML. Extramedullary blast crisis as the initial presentation of CML with bone marrow remaining in chronic phase is an unusual event. Further, extramedullary blast crisis with T lymphoid/myeloid bilineal phenotype as an initial presentation for CML is extremely unusual.

Case Report:

Here, we report the case of a 49-year-old male with rapidly enlarged submandibular lymph nodes. Biopsy specimen from the nodes revealed a characteristic appearance with morphologically and immunohistochemically distinct myeloblasts and T lymphoblasts co-localized in 2 adjacent regions, accompanied by chronic phase of the disease in bone marrow. The presence of the BCR/ABL1 fusion gene within both cellular populations in this case confirmed the extramedullary disease represented a localized T lymphoid/myeloid bilineal blastic transformation of CML. After 3 courses of combined chemotherapy plus tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment, the mass was completely regressed with a 3-log decrease in BCR/ABL1 transcript from baseline. Five months after the diagnosis, the patient showed diminished vision, hand tremors, and weakness of lower extremities. Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of cerebrospinal fluid revealed the presence of myeloid blasts. An isolated central nervous system relapse of leukemia was identified. Following high-dose systemic and intrathecal chemotherapy, the patient continued to do well.

Conclusions:

The possibility of extramedullary blast crisis as an initial presentation in patients with CML should be considered. Further, an isolated central nervous system blast crisis should be considered if neurological symptoms evolve in patients who have shown a good response to therapy.

MeSH Keywords: Blast Crisis; Leukemia, Myelogenous, Chronic, BCR-ABL Positive; Precursor T-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia-Lymphoma; Sarcoma, Myeloid

Background

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal myeloproliferative disorder, which is characterized by the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome generated by the reciprocal translocation t(9: 22) (q34;q11) that results in a BCR/ABL1 fusion gene [1]. Blast crisis represents an advanced phase of the disease, arbitrarily defined as more than 30% of blasts in the blood or bone marrow, or the presence of extramedullary disease. However, extramedullary blast crisis as the initial presentation for CML with bone marrow remaining in the chronic phase has been reported in only 16 reported cases in the past 25 years [2–17]. The lymph node is the most commonly involved site for the extramedullary disease. Immunophenotypic analysis of the blasts shows that 50% of cases with extramedullary disease are classified as myeloid phenotype, 25% as T lymphoid phenotype, and 25% as bilineal phenotype (myeloid and T cell). Surprisingly, no B lymphoid phenotype is reported among CML cases with extramedullary blast crisis as the initial presentation. Previous reports indicated that T lymphoid phenotype is extremely rare, and B lymphoid phenotype (30%), secondary only to myeloid phenotype (70%), is another common immunophenotype of the blasts in blastic phase of CML cases [18].

In this report, we describe the case of a 49-year-old male with CML who presented with bilineal extramedullary (lymph nodes) blast crisis accompanied by chronic phase of disease in bone marrow, and who later developed an isolated central nervous system (CNS) relapse of leukemia. We also show that the extramedullary blastic disease in this case had a characteristic pathological feature with the Ph+ myeloblasts located adjacent to the Ph+ T lymphoblasts within the same involved lymph node.

Case Report

A 49-year-old male was evaluated for rapidly enlarging mass on the left side of the neck at a local hospital in May 2015. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle aspiration biopsy of the mass showed the normal structure of tissue was obscure and replaced by diffused infiltration of atypical lymphocytes. Immunohistochemistry detection revealed that these lymphocytes were positive for CD34, CD7, CD99, and Ki-67 (>50%), scattered positive for TdT, but negative for PAX-5, CD33, CD64, CD3, CD20, and MPO. The histological diagnosis was precursor T cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Bone marrow aspirate smears revealed active hyperplasia, with 79.6% granulocytes (2.8% myeloblasts, 6.8% early promyelocytic cells, 20.8% middle promyelocytic cells, and 14.4% late promyelocytic cells), 15.2% erythropoietic cells, and 2.4% lymphocytes. Of these lymphocytes, atypical lymphocytes were visible. The patient did not receive any treatment.

In June 2015, the patient was admitted to our hospital with complains of night sweating but no fever or weight loss. Physical examination revealed multiple palpable masses on the left side of the neck and submandibular area, with a maximum diameter of 3 cm. The liver and spleen were not palpable below the costal margin. Initial examination of peripheral blood counts showed moderate leukocytosis (20 900/ µl) with 9% middle promyelocytic cells, 7% late promyelocytic cells, 53% neutrophils, 1% basophils, 1% eosinophils, 19% lymphocytes, and 10% monocytes. The repeated bone marrow aspirate smears revealed active hyperplasia with G/E ratio of 10.3:1. The lymphocytes accounted for 12.4%, in which immature lymphocytes were unevenly distributed, with an average of 6.4% (Figure 1A).

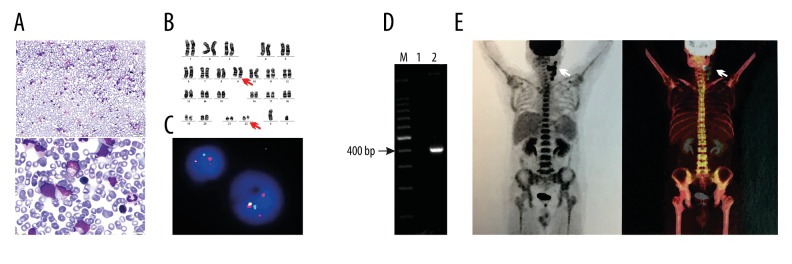

Figure 1.

Morphology, cytogenetics, and molecular features of bone marrow and 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging analysis. (A) Bone marrow aspiration revealing a hypercellular marrow with the presence of 6.4% immature lymphocytes. (B) A G-banded karyotype of bone marrow showing the Ph chromosome: 46 XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) (arrows). (C) FISH on the interphase nuclei of bone marrow using the Vysis Extra Signal probe revealing the typical p210 breakpoint in CML yielding 1 green, 1 red, 1 residual red, and 1 red-green fusion signal. (D) RT-PCR analysis of the mRNA extracted from bone marrow demonstrating p210 BCR/ABL1 rearranged bands (397 bp). Lane 1, marker; Lane 2, distilled water; Lane 3, bone marrow. (E) 18F-FDG PET/CT scanning of the body showing abnormal FDG accumulation in the left side of the neck and submandibular lymph nodes (arrows).

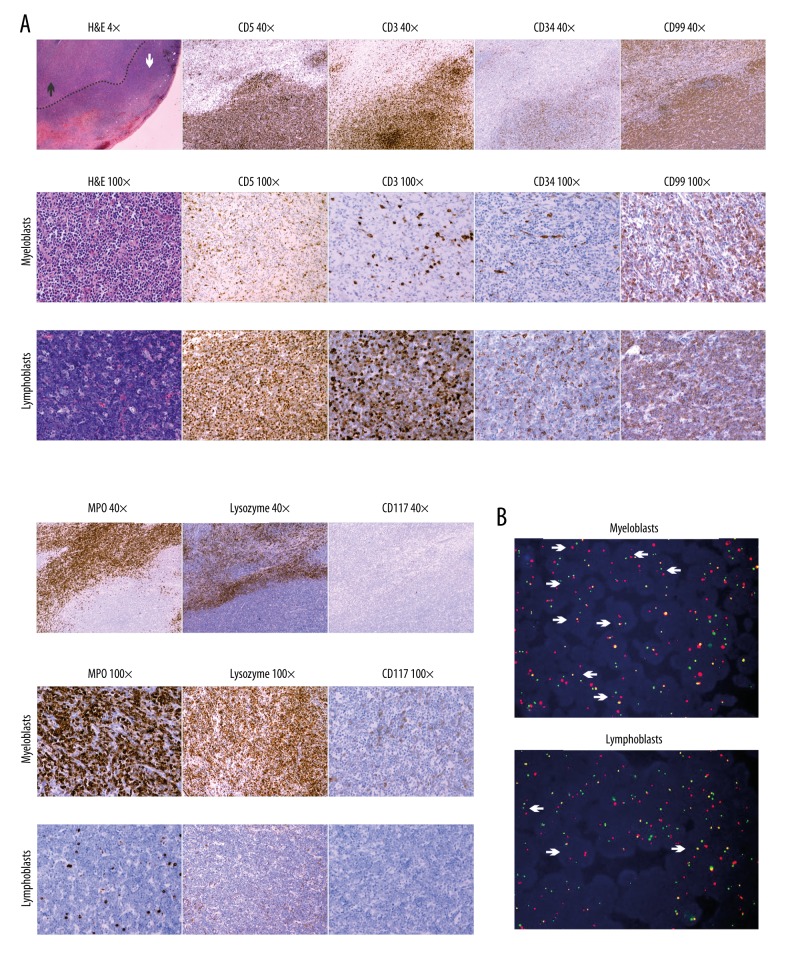

Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of bone marrow revealed abnormal proliferation of myeloid blasts, which were positive for CD34, HLA-DR, CD117, CD33, and CD7. Chromosome analysis identified presence of Ph chromosome in 20 out of 20 cells (Figure 1B). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) showed positive staining for p210 BCR/ABL1 gene rearrangement in 83% of interphase cells (Figure 1C). The e13a2 BCR/ABL1 (p210) fusion transcript was confirmed by quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis, showing a 16.7% proportion of BCR/ABL1 to ABL1 (Figure 1D). There was no alteration in P53 gene. These findings led to the diagnosis of chronic phase CML. 18F-FDG positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scanning revealed abnormal FDG accumulation in multiple lymph nodes in the left side of the neck, with moderately high metabolic activity (SUVmax: 7.0), and high metabolic activity related to the mass in the left submandibular (SUVmax: 14.5; Diametermax: 50 mm) (Figure 1E). A subsequent excisional biopsy of the left submandibular lymph nodes was performed. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed damaged structure of the nodes, and diffused infiltration of 2 populations of blasts with distinct morphology (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated simultaneous proliferation of blast populations of myeloid and lymphoid lineages in adjacent regions within the same lymph node. The myeloblasts were positive for myeloid differentiation markers (MPO and lysozyme) but negative for CD5, CD3, CD99, CD117, CD34, and TdT, which was consistent with myeloid sarcoma. They were surrounded by lymphoblasts positive for precursor lymphoid cell markers (CD34 and CD99) and pan-T markers (CD5 and CD3), but negative for MPO and lysozyme, consistent with T cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (Figure 2A). FISH test for p210 BCR/ABL1 gene rearrangement was positive in both cell populations (Figure 2B). Therefore, the final diagnosis of Ph+ CML with a bilineal extramedullary blast crisis of myeloid sarcoma and precursor T cell lymphoblastic lymphoma was made.

Figure 2.

Histopathology features of the lymph nodes. (A) Microscopic appearance showing the normal architecture of the lymph node substituted by diffuse infiltration of 2 populations of blastic cells with a clear dividing line – the red and sparse staining myeloblasts region (white arrow) and the blue and dense staining T lymphoblasts region (black arrow) (H&E, 4×). The sparse staining region is composed of neoplastic cells with myeloid differentiation, with background rich in blood vessels (H&E, 100×). The cells are strongly positive for MPO and lysozyme, and negative for CD117, CD5, CD3, CD34, and CD99 (immunohistochemistry with hematoxylin counterstain, 40× and 100×). The dense staining region is composed of T lymphoblasts with dense nuclear chromatin and a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and scattered macrophages with starry-sky appearance (H&E, 100×). The cells are strongly positive for CD5, CD3, and CD99; focally positive for CD34; and negative for MPO, lysozyme, and CD117 (immunohistochemistry with hematoxylin counterstain, 40× and 100×). (B) FISH on the paraffin-embedded biopsy specimen using the Vysis Extra Signal probe revealing the presence of p210 breakpoint in both myeloblasts (low cell density area) and T lymphoblasts (high cell density area). Positive cells (arrows) contain 1 green, 1 red, 1 residual red, and 1 red-green fusion signal.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib and induction chemotherapy using vincristine and prednisone was administered. After the initial course of chemotherapy, the enlarged left neck and submandibular nodes experienced a transient shrinkage before progressive re-enlargement. QRT-PCR monitoring of BCR/ABL1 transcript in bone marrow showed an increased ratio of BCR/ABL1 to ABL1 (35.6%), but mutation of BCR/ABL1 kinase domain was not detected by direct sequencing of PCR products. Another TKI, Nilotinib, and combination chemotherapy regimen consisting of mitoxantrone, etoposide, vincristine, prednisone was administered later. After 2 courses of chemotherapy, the enlarged nodes were completely regressed, with a significant decrease of BCR/ABL1 transcript in bone marrow (the ratio of BCR/ABL1 to ABL1 was 0.03%), which was confirmed by ultrasound examination and qRT-PCR, respectively. The patient refused the treatment recommendation of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) due to economic reasons. He was given routine prophylactic intrathecal treatment with cytarabine and dexamethasone from the beginning of the second course of chemotherapy. In November 2015, he complained of diminished vision, hand tremors, and weakness of lower extremities, but no headache or vomiting. Brain MRI results were normal. Lumbar puncture examination showed markedly increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure (>30 cm H2O). Laboratory tests of CSF revealed significantly elevated protein level (1716.3 mg/dl) and normal glucose level (4.4 mmol/L) and leukocyte counts (2×106/L). Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of CSF confirmed presence of myeloid blasts positive for CD34 and HLA-DR, but negative for CD117 and CD7. The diagnosis of CML with CNS blast crisis was confirmed, and treatment initiated with intravenous high-dose methotrexate (3 g/m2, every 2 weeks) and intrathecal cytarabine and dexamethasone (twice a week) was promptly given. Following treatment, the patient’s symptoms were relieved, with normal CSF pressure and negative laboratory test results, and no detectable BCR/ABL1 transcript in bone marrow by qRT-PCR, and to date he continues to be well.

Discussion

Here, we report an unusual case of CML that presented with an extramedullary nodal T lymphoid/myeloid bilineal blast crisis, followed by an isolated CNS relapse of leukemia. This case is unusual in 3 aspects: 1) bilineal extramedullary blast crisis as an initial presentation for CML with bone marrow remaining in chronic phase; 2) extramedullary disease with morphologically and immunophenotypically distinct cell populations distributed in 2 adjacent regions of the same involved lymph node; and 3) isolated CNS relapse after standard therapy with an initial good response.

Extramedullary blast crisis of CML is defined by infiltration of leukemic blasts in areas other than bone marrow, which has been reported in only 4–16% of CML cases during the disease course [4]. As shown in Table 1, CML cases presenting with a bilineal extramedullary disease with bone marrow in chronic phase are rare, with only 4 reported cases. All of these cases had involvement of the lymph nodes with immunophenotypic analysis of the blasts showing T lymphoid/myeloid bilineal phenotype. Surprisingly, no cases with B lymphoid/myeloid phenotype have been reported.

Table 1.

Summary of the reported CML cases presenting with a bilineal extramedullary disease with bone marrow in chronic phase.

| No. | Age/sex | BM at diagnosis | Extramedullary presentation of blastic crisis at diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytogenetic /FISH | RT-PCR | Biopsy site | Bilineal immunophenotype (positive antigen) | Cytogenetic /FISH | RT-PCR | |||||

| 1 | 14 /M | Ph | P210 BCR/ABL1 | Lymph node | T-lymphoid/ myeloid (Blasts: CD3, TdT. Adjacent tissue: MPO, CD15, lysozyme) | Ph | Not done | Mitoxantrone, Cytarabine, Dasatanib. Allo-HSCT | Alive 0.8 year | [7] |

| 2 | 14 /M | Ph | Not done | Lymph node | T-lymphoid/ myeloid (MPO, CD13, CD33, CD3, CD7) | Not done | Not done | Prednisolone, Vindesine, Daunorubicin, L-asparaginase. Per MCP 841 protocol | Dead 0.1 year | [8] |

| 3 | 44 /F | Ph | P190 BCR/ABL1 | Lymph node | T-lymphoid/ myeloid (MPO, CD5, CD7, CD13, CD33, CD34, HLA-DR) | Ph | P190 BCR/ABL1 | Hydroxyurea | Not available | [13] |

| 4 | 47 /M | Ph | Not done | Lymph node | T-lymphoid/ myeloid (CD5, CD7, CD33) | Ph | Not done | Etoposide | Dead 2.8 years | [15] |

Among the cases of extramedullary blast crisis at initial diagnosis showing bilineal phenotype (Table 1), there has been only 1 case with 1 type of blasts located adjacent to, but distinct from, the other type of blasts with different lineage phenotype [8]. Chen et al. reported a 14-year-old male who presented with CML in blast phase with segregated extramedullary myeloid sarcoma and T lymphoblastic lymphoma. The pathological examination of the lymphadenectomy sample showed T lymphoblasts in the lymph nodes and myeloblasts in the adjacent soft tissue [8]. The involved lymph nodes in our case carried a typical immunophenotype consistent with bilineal extramedullary disease, showing co-existence of 2 distinct lineages of blasts, but not co-expressing normally exclusive markers on a single type of blast. Both blast populations were positive for BCR/ABL1 translocation, which confirmed extramedullary disease representing a localized blastic transformation of CML. The above observations indicate that T lymphoid and myeloid blasts share common Ph+ progenitors, which may be involved in the development of blastic transformation in CML.

CML in blast crisis often exhibits CNS involvement [19]. Despite achieving an initial major molecular response (3-log decrease in BCR/ABL1 transcript from baseline) to TKI in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy, our case was found to have blasts of myeloid lineage in the CNS 5 months after the diagnosis, consistent with CNS relapse. As imatinib does not penetrate the blood–brain barrier, isolated CNS blast crises have been reported in about 20% of patients with CML in blast crisis treated with imatinib [19]. Although the second-generation TKIs (nilotinib and dasatinib) have an improved penetration of the blood–brain-barrier, single cases of isolated CNS blast crises have also been reported [20]. Therefore, the CNS has to be regarded as a sanctuary site of relapse for CML.

Conclusions

The possibility of extramedullary blast crisis as an initial presentation in patients with CML should be considered. This may be more important in patients who initially present with lymphadenopathy, particularly those without significant abnormalities in bone marrow morphology. Cytogenetic and molecular diagnoses are particularly important in this situation. Further, an isolated CNS blast crisis should be considered if neurological symptoms evolve in patients who have shown a good response to therapy. The isolated CNS relapse of leukemia can be controlled by high-dose systemic and intrathecal chemotherapy.

References:

- 1.Bartram CR, de Klein A, Hagemeijer A, et al. Translocation of c-ab1 onco-gene correlates with the presence of a Philadelphia chromosome in chronic myelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1983;306(5940):277–80. doi: 10.1038/306277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng DF, Chang C, Li JP, et al. Extramedullary T-lymphoblastic blast crisis in chronic myelogenous leukemia: A case report of successful diagnosis and treatment. Exp Ther Med. 2015;(3):850–52. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy RA, Mardones MA, Burch MM, Krause JR. Bilineal T lymphoblastic and myeloid blast transformation in chronic myeloid leukemia with TP53 mutation-an uncommon presentation in adults. Curr Oncol. 2014;21(1):e147–50. doi: 10.3747/co.21.1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy RA, Mardones MA, Burch MM, Krause JR. Myeloid sarcoma as the presenting symptom of chronic myelogenous leukemia blast crisis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2014;27(3):246–49. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2014.11929127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukamoto S, Ota S, Ohwada C, et al. Extramedullary blast crisis of chronic myelogenous leukemia as an initial presentation. Leuk Res Rep. 2013;2(2):67–69. doi: 10.1016/j.lrr.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin GN, Zou P, Chen WX, et al. Fluorescent in situ hybridization diagnosis of extramedullary nodal blast crisis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41(3):253–56. doi: 10.1002/dc.21795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go JH, Park J. Extramedullary blast crisis of secondary CML accompanying marrow fibrosis. Korean J Hematol. 2012;47(4):243. doi: 10.5045/kjh.2012.47.4.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Rutledge JC, Wu D, et al. Chronic myelogenous leukemia presenting in blast phase with nodal, bilineal myeloid sarcoma and T-lymphoblastic lymphoma in a child. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2013;16(2):91–96. doi: 10.2350/12-07-1230-CR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganessan K, Goel R, Kumar K, Bakhshi S. Biphenotypic extramedullary blast crisis as a presenting manifestation of Philadelphia chromosome-positive CML in a child. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;24(3):195–98. doi: 10.1080/08880010701198787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aleem A, Siddiqui N. Chronic myeloid leukemia presenting with extramedullary disease as massive ascites responding to imatinib mesylate. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46(7):1097–99. doi: 10.1080/10428190500096781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin CC, Medeiros LJ, Glassman AB, Lin P. t(8;21)(q22;q22) in blast phase of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121(6):836–42. doi: 10.1309/H8JH-6L09-4B9U-3HGT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakakura M, Ohishi K, Nomura K, et al. Case of chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia with an abdominal hematopoietic tumor of leukemic clone origin. Am J Hematol. 2004;77(2):167–70. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori T, Yamazaki R, Ikeda Y, Okamoto S. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for the BCR-ABL fusion gene in a patient with imatinib mesylate-resistant chronic myelogenous leukaemia in extramedullary blast crisis. Br J Haematol. 2003;121(4):533. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaguchi H, Inokuchi K, Shinohara T, Dan K. Extramedullary presentation of chronic myelogenous leukemia with p190 BCR/ABL transcripts. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1998;102(1):74–77. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(97)00298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacob A, Rowlands DC, Patton N, Holmes JA. Chronic granulocytic leukaemia presenting with an extramedullary T lymphoblastic crisis. Br J Haematol. 1994;88(2):435–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb05050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konaka Y, Namiuchi S. Extramedullary blast crisis of mixed precursor T lymphoblastic and myeloblastic features in a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia successfully treated with low-dose oral etoposide. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993;34(12):1556–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akashi K, Mizuno S, Harada M, et al. T lymphoid/myeloid bilineal crisis in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Exp Hematol. 1993;21(6):743–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid AG, De Melo VA, Elderfield K, et al. Phenotype of blasts in chronic myeloid leukemia in blastic phase-Analysis of bone marrow trephine biopsies and correlation with cytogenetics. Leuk Res. 2009;33(3):418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindhorst SM, Lopez RD, Sanders RD. An unusual presentation of chronic myelogenous leukemia: A review of isolated central nervous system relapse. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(7):745–49. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaur S, Torabi AR, Corral J. Isolated central nervous system relapse in two patients with BCR-ABL-positive acute leukemia while receiving a next-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor. In Vivo. 2014;28(6):1149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]