Abstract

Objective

To determine the association of antenatal magnesium sulfate with cerebellar hemorrhage in a prospective cohort of premature newborns evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Study design

Cross-sectional analysis of baseline characteristics from a prospective cohort of preterm newborns (<33 weeks gestation) evaluated with 3T-magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shortly after birth. Exclusion criteria were clinical evidence of a congenital syndrome, congenital infection, or clinical status too unstable for transport to MRI. Antenatal magnesium sulfate exposure was abstracted from the medical records and the indication was classified as obstetric or neuroprotection. Two pediatric neuroradiologists, blinded to the clinical history, scored axial T2-weighted and iron-susceptibility MRI sequences for cerebellar hemorrhage. The association of antenatal magnesium sulfate with cerebellar hemorrhage was evaluated using multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for postmenstrual age at MRI and known predictors of cerebellar hemorrhage.

Results

Cerebellar hemorrhage was present in 27/73 (37%) newborns imaged at a mean postmenstrual age of 32.4 ± 2 weeks. Antenatal magnesium sulfate exposure was associated with a significantly reduced risk of cerebellar hemorrhage. Adjusting for postmenstrual age at MRI, and predictors of cerebellar hemorrhage, antenatal magnesium sulfate was independently associated in our cohort with decreased cerebellar hemorrhage (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.049–0.65, P=0.009).

Conclusion

Antenatal magnesium sulfate exposure is independently associated with a decreased risk of MRI-detected cerebellar hemorrhage in premature newborns, which could explain some of the reported neuroprotective effects of magnesium sulfate.

Keywords: brain injury, premature, infants, neuroprotection, MRI

In spite of gains in neonatal survival following preterm birth, the rate of neurodevelopmental disabilities in children born prematurely has remained relatively static.1,2 Although improved neurodevelopmental outcomes have been reported among extremely premature newborns near the limit of viability in some centers,3 broader strategies are required to optimize outcomes on a population level. There is an urgent need to identify modifiable risk factors for brain injury in this high-risk population in order to improve neurodevelopmental outcome after preterm birth. Meta-analyses have shown that antenatal magnesium sulfate is associated with a reduced risk of cerebral palsy in premature infants.4–6 A recent study has shown that antenatal magnesium sulfate is associated with a reduced risk of white matter echolucencies and echodensities on cranial ultrasound; however, this effect only partially explains the reduction of cerebral palsy among exposed newborns.7 Antenatal exposure to magnesium sulfate has not been associated with a reduction in brain injuries known to cause cerebral palsy, such as cystic white matter injury or intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), in several randomized controlled trials that used ultrasound to diagnose brain injury.8–12 The underlying explanation for the neuroprotective effects of magnesium sulfate in premature newborns is unclear, and further investigation for brain injury with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help clarify this.

Cerebellar hemorrhage is gaining recognition as a common form of brain injury in premature newborns.13–21 Detection of cerebellar hemorrhage by MRI has been reported in up to 19% of preterm infants <32 weeks’ gestation.13,16 Cerebellar hemorrhage may be underdiagnosed if specific MRI sequences are not performed, such as susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI).

Predictors of cerebellar hemorrhage in prior studies have included advanced maternal age, primiparity, cesarean delivery, extremely-low-birth weight (<750 grams), longer duration of mechanical ventilation, and severe IVH.13,15–17 MRI-detected cerebellar hemorrhage in premature newborns is associated with impaired cerebellar growth,22 and thinning of the cerebral cortex,23 as well as motor, cognitive and behavioral deficits in early childhood.13,18,19

The relationship between magnesium sulfate and cerebellar hemorrhage in premature newborns is u n known. We hypothesized that antenatal magnesium sulfate exposure is associated with a reduced risk of cerebellar hemorrhage. To address this hypothesis, we performed a cross-sectional analysis of the association of antenatal magnesium sulfate with cerebellar hemorrhage using a prospective cohort of premature newborns imaged with advanced MRI soon after birth as part of an ongoing study of cerebellar development.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of baseline characteristics from a prospective cohort of 73 premature newborns admitted to the intensive care nursery at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), between August 2011 and August 2015. Over the study period, 318 newborns <33 weeks’ gestation were screened for eligibility. Exclusion criteria for the cohort included clinical evidence of a congenital malformation or syndrome (n=25), congenital infection (n=2), or clinical status too unstable for transport to MRI (n=52). Among the 239 newborns that met inclusion criteria, 209 parents of eligible newborns were approached for study enrollment (30 were not approached as return transport to a local hospital was anticipated). Of 209 parents approached for study participation, 73 consented, 74 declined, and 62 did not respond. Subjects that consented for study participation were representative of the UCSF intensive care nursery census with regards to demographic data, such as gestational age and birth weight. Further clinical data regarding subjects that declined or did not respond was unavailable. A subset of this cohort was included in our prior study of the association between cerebellar hemorrhage and cerebellar volume (n=56).22 Parental consent was obtained following a protocol approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research.

MRI

MRI scans were obtained as soon after birth as clinically feasible. Clinical stability for MRI was at the discretion of the treating neonatologist. A custom MRI-compatible incubator with a specialized neonatal head coil was used to provide a quiet, well-monitored environment for newborns, minimizing patient movement and improving the signal-to-noise ratio. MRI scans were acquired using a 3T-scanner (General Electric Discovery MR750; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) and a specialized, high-sensitivity, neonatal head coil built into the MRI-compatible incubator (custom-built). MRI scans included axial fast spin-echo T2-weighted images (repetition time [TR], 5000 ms; echo time [TE], 120 ms; field of view [FOV], 20 cm with 256 × 256 matrix; slice thickness, 3 mm; gap, 0 mm), sagittal volumetric 3-dimensional spoiled gradient echo T 1 - weighted images (inversion time 450 ms; TE, minimal; FOV, 18 mm; 1.0 mm isotropic), and SWI (TR, minimal; TE, 24.1 ms; FOV, 18 mm; slice thickness, 2.2 mm, obtained in 44 subjects (60.3%).

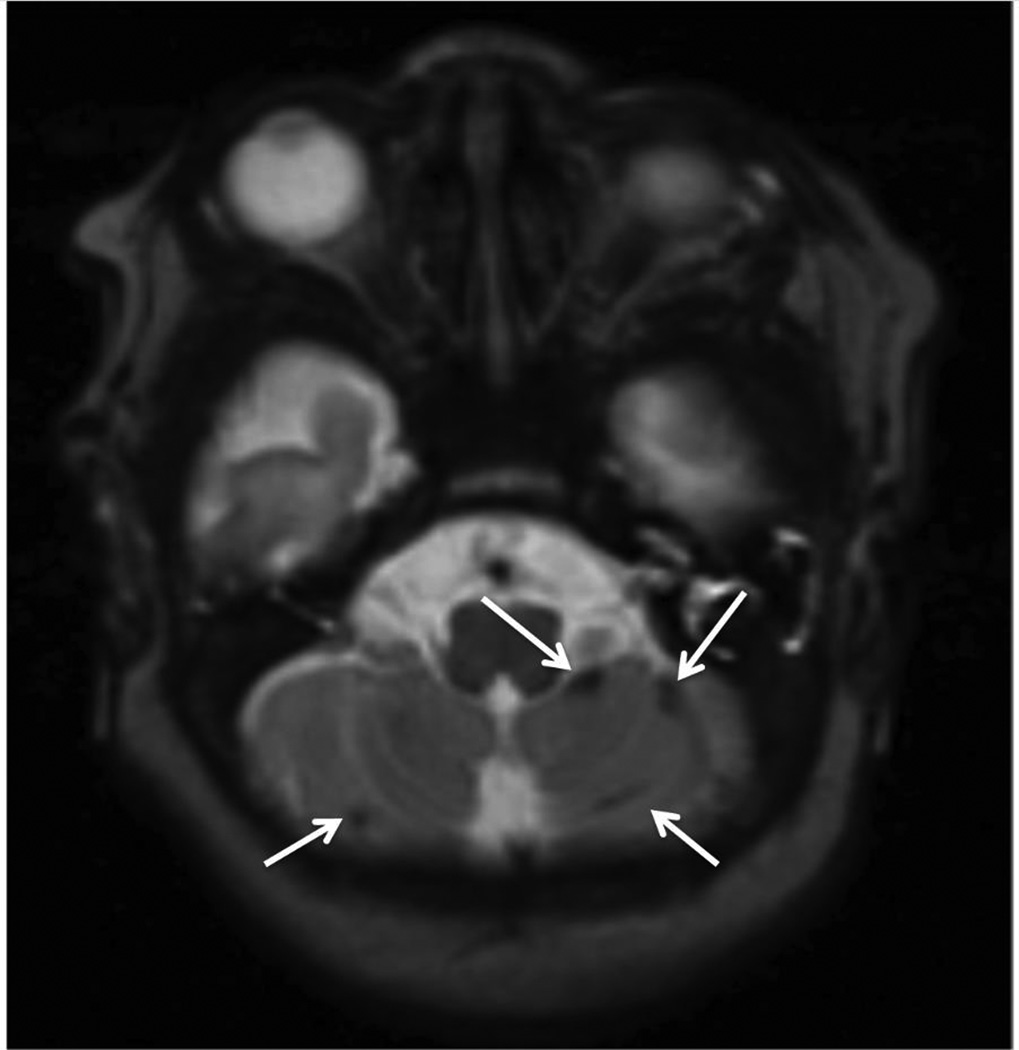

Two pediatric neuroradiologists (AJB and MLH) evaluated all MRI scans blinded to the clinical history (other than premature birth) and scored the severity of brain injuries by consensus. Axial T2-weighted and, when obtained, susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI, a MRI sequence that is particularly sensitive to compounds which distort the local magnetic field and, as such, make the sequence very useful in detecting blood products24) were evaluated for the presence of cerebellar hemorrhage (Figure). The size of cerebellar hemorrhage was classified on the basis of T2 images, and SWI when available, as <3 mm, or ≥3 mm. If more than one focus of cerebellar hemorrhage was present, the diameter of total hemorrhage in the image with the largest amount of hemorrhage was recorded.

Figure.

MRI-detected cerebellar hemorrhage. Axial T2-weighted MRI illustrating multiple foci of cerebellar hemorrhage (white arrows).

The number of foci of cerebellar hemorrhage was characterized as 1–3, or >3. The severity of white matter injury on T1-weighted MRI was scored according to our published criteria and classified as absent/mild and moderate/severe.25 IVH was scored according to the Papile grading system.26 Papile grades 1 and 2 were classified as mild IVH. Papile grade 3 and intraparenchymal hemorrhage were classified as severe IVH.

Clinical data

Trained research nurses blinded to the MRI findings reviewed medical records and extracted clinical data. Maternal and antenatal variables included exposure to prenatal steroids and magnesium sulfate, as well as maternal age, primiparity, maternal smoking, placenta previa, preeclampsia, and twin gestation. The indication for magnesium sulfate was classified as obstetric for tocolysis and treatment of preeclampsia, or neuroprotection, according to the medical records. Demographic variables included gestational age at birth, birth weight, and sex. Very low birth weight was defined as <1000 grams at birth. Perinatal variables included placental abruption, chorioamnionitis, delivery mode, delivery at an outside hospital (outborn), and endotracheal intubation during resuscitation at birth. Chorioamnionitis was diagnosed clinically (maternal fever >38° C during labor or fetal tachycardia with uterine tenderness, treated with antibiotics).27 Neonatal variables included duration of mechanical ventilation, infection, hypotension, symptomatic patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), neonatal surgery, and chronic lung disease. Newborns with culture-positive sepsis, clinical signs of sepsis with negative blood culture, or meningitis were classified as having infection. Hypotension was defined as a period of sustained low blood pressure treated with intravenous fluid bolus and/or inotropes. Newborns with clinical signs of PDA (prolonged systolic murmur, bounding pulses, and hyperdynamic precordium), and evidence of left-to-right flow through the PDA on echocardiogram were classified as having symptomatic PDA. NEC was diagnosed according to Bell’s stage II criteria.28 Chronic lung disease was defined as an oxygen requirement at 36 weeks postmenstrual age.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). A cross-sectional analysis of baseline characteristics of newborns enrolled in the prospective cohort was performed. Clinical characteristics were compared between newborns with cerebellar hemorrhage and those without cerebellar hemorrhage using Fisher exact test or chi-squared test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. The magnitude of the association between categorical predictors and cerebellar hemorrhage was calculated using the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Variables with association to cerebellar hemorrhage (P<0.1) were evaluated as predictors of cerebellar hemorrhage using multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for postmenstrual age at the time of MRI.

Results

The mean gestational age of infants in the cohort was 28.3 weeks (SD 2.2 weeks). MRI was obtained at a mean postmenstrual age of 32.4 weeks (SD 2). Among 73 newborns, 27 (37%) had evidence of cerebellar hemorrhage on MRI soon after birth (Table I). Foci of cerebellar hemorrhage measured <3 mm in 15 newborns (15/27, 55.6%), and ≥3 mm in 12 (12/27, 44.4%). There were 1–3 foci of cerebellar hemorrhage in 15 newborns, and >3 foci of cerebellar hemorrhage in 12.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by cerebellar hemorrhage

| Characteristic | cerebellar hemorrhage N=27 |

No cerebel lar hemorr hage N=46 |

P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Male, N (%) | 12 (44.4) | 24 (52.2) | 0.52 |

| Gestational age at birth, weeks, mean ± SD | 27.8 ± 2.3 | 28.6 ± 2.0 | 0.076 |

| Birth weight median (IQR), grams | 890 (700, 1140) | 1200 (950, 1450) | 0.0079 |

| Maternal/Antenatal | |||

| Maternal age, years, mean ± SD | 29.7 ± 6.8 | 28.8 ± 6.4 | 0.48 |

| Primigravida, N (%) | 11 (40.7) | 15 (32.6) | 0.61 |

| Twin gestation, N (%) | 11 (40.7) | 22 (47.8) | 0.63 |

| Maternal smokingb N (%) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (4.3) | 0.62 |

| Placenta previa, N (%) | 4 (14.8) | 2 (4.3) | 0.19 |

| Pre-eclampsia, N (%) | 5 (18.5) | 12 (26.1) | 0.57 |

| Steroids, N (%) | 22 (81.5) | 41 (89.1) | 0.48 |

| Magnesium sulfate, N (%) | 0.021 | ||

| None | 14 (51.9) | 10 (21.7) | |

| Obstetric indication | 10 (37) | 22 (47.8) | |

| Neuroprotection | 3 (11.1) | 14 (30.4) | |

| Perinatal | |||

| Placental abruption, N (%) | 5 (18.5) | 7 (15.2) | 0.82 |

| Chorioamnionitis, N (%) | 5 (18.5) | 7 (15.2) | 0.82 |

| Outborn, N (%) | 7 (25.9) | 16 (34.8) | 0.43 |

| Cesarean delivery, N (%) | 20 (74.1) | 28 (60.9) | 0.25 |

| Intubation at birth, N (%) | 18 (66.7) | 15 (32.6) | 0.005 |

| Postnatal | |||

| Hypotension, N (%) | 21 (77.8) | 21 (45.7) | 0.007 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus, N (%) | 12 (44.4) | 8 (17.8) | 0.014 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis, N (%) | 0 | 3 (6.5) | 0.29 |

| Infection, N (%) | 12 (44.4) | 16 (34.8) | 0.41 |

| Mechanical ventilation ≥7 days, N(%) | 14 (51.9) | 10 (21.7) | 0.011 |

| Neonatal surgery, N(%) | 6 (22.2) | 5 (10.9) | 0.31 |

| Chronic lung disease, N (%) | 10 (37) | 11 (23.9) | 0.19 |

| Imaging | |||

| Postnatal age at MRI, weeks, median (IQR) | 3.9 (2, 7.6) | 3.9 (2, 4.1) | 0.12 |

| SWI obtained, N (%) | 13 (48.1) | 31 (67.4) | 0.11 |

| White matter injuryc, N (%) | 0.47 | ||

| Absent/Mild | 21 (91.3) | 35 (83.3) | |

| Moderate/Severe | 2 (8.7) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage, N (%) | 0.29 | ||

| None | 16 (59.3) | 35 (76.1) | |

| Mild (Grade 1 or 2) | 7 (25.9) | 8 (17.4) | |

| Severe (Grade 3 or IPL) | 4 (14.8) | 3 (6.5) | |

SD=standard deviation; IQR=interquartile range; IPL=intraparenchymal hemorrhage; SWI=susceptibility-weighted imaging

Categorical predictors were compared using Fisher exact or chi-squared test, and continuous predictors were compared using Kruskal-Wallis test

All subjects with maternal smoking were exposed to marijuana, one was also exposed to tobacco.

White matter injury not assessed in 8 newborns due to motion on MRI.

Newborns with cerebellar hemorrhage were younger at birth (P=0.076) and had lower birth weight (P=0.0079). Postmenstrual and postnatal ages at MRI were not associated with cerebellar hemorrhage. Exposure to antenatal magnesium sulfate was associated with a significantly reduced risk of cerebellar hemorrhage (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26–0.81, P=0.008). Maternal factors and mode of delivery were not associated with cerebellar hemorrhage. Additional clinical factors associated with cerebellar hemorrhage included intubation at birth, hypotension, PDA, and mechanical ventilation for 7 or more days (all P≤0.014).

Moderate/severe white matter injury was present on MRI in 9 newborns (12.3%), mild IVH in 15 (20.5%), and severe IVH in 7 (9.6%). There was no association between cerebellar hemorrhage, and white matter injury or severity of IVH, although IVH appeared to be more common in newborns with cerebellar hemorrhage (Table I).

Characteristics associated with magnesium sulfate administration

Antenatal magnesium sulfate was administered to mothers of 49 newborns (67%) in the cohort. The primary indication for magnesium sulfate was obstetric in 32 exposed newborns (65.3%), and neuroprotection in 17 (34.7%). Magnesium sulfate administration was strongly associated with administration of prenatal steroids (RR 3.73, 95% CI 1.071–13, P=0.0006). There was no association between other maternal factors, including advanced maternal age or birth at an outside hospital, and magnesium sulfate administration. Newborns exposed to magnesium sulfate tended to be of a higher birth weight compared with unexposed newborns (median 1160, interquartile range [IQR] 805–1440, vs. median 975, IQR 830–1168, P=0.095); however, gestational age at birth was similar in both groups.

Magnesium sulfate exposure was associated with a reduction of both punctate, and larger foci of cerebellar hemorrhage, as well as a reduction in the number of foci of cerebellar hemorrhage (Table II). We also evaluated the relationship of magnesium sulfate with white matter injury and IVH, but could not find an association.

Table 2.

Brain injury on MRI by antenatal magnesium sulfate exposure

| MRI findings | Antenatal magnesium sulfate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed N=49 |

Unexposed N=24 |

P-valuea | |

| Postmenstrual age at MRI, median (IQR), weeks | 32.7 (31.4, 33.4) | 31.9 (30.9, 33.2) | 0.38 |

| SWI obtained, N (%) | 30 (61.2) | 14 (58.3) | 0.81 |

| Cerebellar hemorrhage, N (%) | 0.008 | ||

| Absent | 36 (73.5) | 10 (41.7) | |

| Present | 13 (26.5) | 14 (58.3) | |

| Size of cerebellar hemorrhage, N (%) | 0.018 | ||

| <3 mm | 6 (12.2) | 9 (37.5) | |

| ≥3 mm | 7 (14.3) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Number of foci of cerebellar hemorrhage, N (%) | 0.028 | ||

| 1–3 foci | 7 (14.3) | 8 (33.3) | |

| >3 foci | 6 (12.2) | 6 (25) | |

| White matter injuryb N (%) | 0.53 | ||

| Absent/Mild | 38 (88.4) | 18 (81.8) | |

| Moderate/Severe | 5 (11.6) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage, N (%) | 0.23 | ||

| None | 37 (75.5) | 14 (58.3) | |

| Mild (Grade 1 or 2) | 9 (18.4) | 6 (25) | |

| Severe (Grade 3 or IPL) | 3 (6.1) | 4 (16.7) | |

IQR=interquartile range; IPL=intraparenchymal hemorrhage; SWI=susceptibility-weighted imaging

Categorical predictors were compared using Fisher exact or chi-squared test, and continuous predictors were compared using Kruskal-Wallis test

White matter injury not assessed in 8 infants due to motion on MRI

Antenatal magnesium sulfate exposure is associated with reduced cerebellar hemorrhage

Predictors of cerebellar hemorrhage were evaluated using multivariable logistic regression (Table III). Adjusting for postmenstrual age at MRI, very-low-birth-weight, intubation at birth, prolonged mechanical ventilation, hypotension, and symptomatic PDA, antenatal magnesium sulfate exposure was independently associated with an 82% reduction in the odds of cerebellar hemorrhage (odds ratio [OR] 0.18, 95% CI 0.049–0.65, P=0.009). Because prenatal steroids were strongly associated with magnesium sulfate administration, we further adjusted the model for prenatal steroid exposure and found that magnesium sulfate exposure resulted in an even greater reduction of cerebellar hemorrhage (OR 0.11, 95% CI 0.025–0.50, P=0.004).

Table 3.

Clinical predictors of cerebellar hemorrhage

| Unadjusted odds ratioa (95% CI) |

P-value | Adjusted odds ratiob (95% CI) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very low birth weight (<1000 g) | 4.12 (1.5–11.32) | 0.006 | 3.57 (0.049–14.22) | 0.071 |

| Postmenstrual age at MRI, weeks | 1.28 (0.97–1.66) | 0.080 | 1.43 (0.97–2.09) | 0.064 |

| Magnesium sulfate | 0.26 (0.092–0.72) | 0.010 | 0.18 (0.049–0.65) | 0.009 |

| Intubation at birth | 4.13 (1.51–11.35) | 0.006 | 3.43 (0.77–15.35) | 0.11 |

| Hypotension | 4.17 (1.42–12.23) | 0.009 | 1.16 (0.25–5.48) | 0.85 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 3.7 (1.26–10.86) | 0.017 | 2.60 (0.59–11.5) | 0.21 |

| Ventilation ≥7 days | 1.058 (1.00–1.12) | 0.060 | 0.79 (0.14–4.35) | 0.79 |

Predictors evaluated on univariate logistic regression if association P<0.1 on comparison between newborns with and without cerebellar hemorrhage.

Multivariate logistic regression model adjusting for all variables in the table.

The relationship between the indication for magnesium sulfate and cerebellar hemorrhage was also evaluated in the multivariable model. Exposure to magnesium sulfate for obstetric indications was independently associated with reduced odds of cerebellar hemorrhage (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.053–0.83, P=0.026). Magnesium sulfate administered for neuroprotection was also independently associated with reduced odds of cerebellar hemorrhage (OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.019–0.77, P=0.025).

Discussion

Cerebellar hemorrhage is a common finding on MRI soon after birth in this cohort of premature newborns <33 weeks’ gestation. Antenatal magnesium sulfate was selectively associated with a reduced risk of cerebellar hemorrhage, but not other forms of brain injury including IVH and white matter injury. After adjustment for confounding factors, antenatal magnesium sulfate was independently associated with an even greater reduction in cerebellar hemorrhage. Our findings suggest that the reduced risk of MRI-detected cerebellar hemorrhage may explain a reason for the neuroprotective effects of magnesium sulfate in premature newborns.

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have shown that antenatal magnesium sulfate reduces the risk of cerebral palsy in children born prematurely without increasing the risk of death.4–6 Mechanisms proposed to explain the neuroprotective effects of magnesium sulfate include stabilization of rapid fluctuations in blood pressure, and increased cerebral blood flow.29,30 In animal models, magnesium sulfate decreases injury after hypoxia-ischemia by decreasing inflammatory cytokines, free radicals, and calcium-induced excitotoxicity.31,32 However, antenatal magnesium sulfate was not associated with a decreased risk of brain injuries known to cause cerebral palsy, such as severe IVH or cystic white matter injury, in several randomized trials that used ultrasound to diagnose brain injury.8–12 A recent subset analysis of one the randomized trials12 focused on newborns <32 weeks at birth, and showed that magnesium sulfate was associated with a reduced risk of echolucencies and echodensities on cranial ultrasound, although this only partially explained the reduction in cerebral palsy among exposed newborns in their cohort.7 Our findings suggest that the neuroprotective effects of magnesium sulfate might be mediated through a reduction in cerebellar hemorrhage, although the mechanism is unclear.

The Committee on Obstetric Practice and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommends that physicians electing to use magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection should develop specific guidelines regarding inclusion criteria and treatment regimens similar to one of the larger randomized trials.33 Subsequent to the committee opinion, implementation of magnesium sulfate protocols for fetal neuroprotection has varied across different institutions in the United States,34 indicating opportunities to increase access to this therapy to a greater proportion of women at risk of preterm birth. Our data have important public health implications, given that cerebellar hemorrhage is associated with long-term disability.17–19 Our findings support a wider usage of this safe and cost-effective intervention35 to women at risk of preterm birth to promote fetal neuroprotection.

The prevalence of cerebellar hemorrhage in our cohort is 2–3 fold higher compared with prior studies,13–19 suggesting that higher resolution imaging with 3T-MRI with thin cuts through the cerebellum may be more sensitive for the detection of cerebellar hemorrhage in premature newborns. In our cohort, cerebellar hemorrhage was more common than white matter injury, which is considered to be the dominant pattern of brain injury in preterm infants. We have previously demonstrated that cystic36 and MRI-detected non-cystic white matter injury37 declined over time in contemporary cohorts. Because the prevalence of neurodevelopmental disabilities has remained relatively static in children born prematurely,1 other forms of brain injury such as cerebellar hemorrhage might account for a large portion of the burden of disability.19,38

The high prevalence of cerebellar hemorrhage in our study, and high risk of pervasive neurodevelopmental disabilities in preterm infants with cerebellar hemorrhage17–19 are consistent with this hypothesis. We have recently reported that cerebellar hemorrhage are associated with impaired cerebellar growth in preterm newborns.22 Limperopoulos et al have shown that cerebellar injury in preterm newborns is associated with impaired growth of specific cerebral regions,23 which in turn is associated with regional-specific functional deficits.39 Taken together, these studies suggest that cerebellar hemorrhage may lead to neurodevelopmental disabilities through disruption of cerebellar-cortical connections secondary to impaired cerebellar growth.

Our study has some limitations. We performed a secondary, cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort study. Infants who were clinically unstable for MRI were excluded and then only 73 of 209 eligible parents approached enrolled in the study. This small sample size could lead to lack of power or selection bias, For example, because the clinical predictors associated with an increased risk of cerebellar hemorrhage were all markers of more severe critical illness, the exclusion of unstable infants likely resulted in an underestimation of the rate of cerebellar hemorrhage. Although there was heterogeneity in the timing of MRI, subjects were scanned as soon as possible after birth. Because early extubation to non-invasive ventilatory support is common at our center, the timing of MRI was delayed in some subjects, as SiPAP is not compatible with MRI. Importantly, there was no association between the timing of imaging and presence of cerebellar hemorrhage. Our study is strengthened by the use of the same MR scanner and imaging acquisition sequences. Over half of the subjects in our cohort had SWI, which is more sensitive in the detection of small areas of hemorrhage.24 Detection of cerebellar hemorrhage was not more common in newborns in whom SWI was obtained. Moreover, the proportion of newborns with SWI was similar in magnesium sulfate exposed and unexposed groups, indicating that the observed association of magnesium sulfate and decreased cerebellar hemorrhage does not reflect measurement bias. Evaluation of a larger number of subjects with SWI would improve the analysis of our findings, in order to characterize better the prevalence, size, and location of cerebellar hemorrhage and to disentangle its relationship with the severity of IVH. Newborns in our cohort were not randomized to receive magnesium sulfate, and we cannot exclude residual confounding as a cause for the association of magnesium sulfate exposure with decreased cerebellar hemorrhage. Lastly, details regarding the dosage of magnesium sulfate and timing of administration were not available.

There is an urgent need to identify modifiable risk factors for brain injury in preterm newborns in order to improve long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. Antenatal exposure to magnesium sulfate is associated with a reduced risk of cerebellar hemorrhage in this cohort of premature newborns prospectively evaluated with MRI soon after birth, which might explain the neuroprotective effects of magnesium sulfate. The high prevalence of cerebellar hemorrhage in our cohort indicates the importance of further study to understand how the size and location of cerebellar hemorrhages affect cerebellar growth, cerebellar-cortical connections, and neurodevelopment in children born prematurely.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NS35902, NS046432, EB009756). D.G. is supported by the University of California, San Francisco, Preterm Birth Initiative, which is funded by Marc and Lynne Benioff and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

We acknowledge the neonatal nurses of the Pediatric Clinical Research Center at UCSF, whose skill and expertise made this study possible. We thank Xiaoyue M. Guo, BA, for her comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations and acronyms

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PDA

Patent ductus arteriosus

- SWI

Susceptibility-weighted imaging

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Behrman RE, Stith Butler A. Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes Board on Health Sciences Outcomes: Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood NS, Costeloe K, Gibson AT, Hennessy EM, Marlow N, Wilkinson AR EPICure Study Group. The EPICure study: associations and antecedents of neurological and developmental disability at 30 months of age following extremely preterm birth. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F134–F140. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.052407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Younge N, Smith PB, Gustafson KE, Malcolm W, Ashley P, Cotten CM, et al. Improved survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes among extremely premature infants born near the limit of viability. Early Hum Dev. 2016;95:5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R. Antenatal magnesium sulfate for the prevention of cerebral palsy in preterm infants less than 34 weeks’ gestation: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:595–609. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costantine MM, Weiner SJ. Effects of antenatal exposure to magnesium sulfate on neuroprotection and mortality in preterm infants: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:354–364. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ae98c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle LW, Crowther CA, Middleton P, Marret S, Rouse D. Magnesium sulfate for women at risk of preterm birth for neuroprotection of the fetus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD004661. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004661.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirtz DG, Weiner SJ, Bulas D, DiPietro M, Seibert J, Rouse DJ, et al. Antenatal magnesium and cerebral palsy in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2015;167:834–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magee L, Sawchuck D, Synnes A, von Dadelszen P. SOGC Clinical Practice Guideline: Magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33:516–529. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34886-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Doyle LW, Haslam RR. Effect of magnesium sulfate given for neuroprotection before preterm birth: a randomized controlled trial. Australasian Collaborative Trial of Magnesium Sulphate (ACTOMg SO4) Collaborative Group. JAMA. 2003;290:2669–2676. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.20.2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marret S, Marpeau L, Zupan-Simunek V, Eurin D, Leveque C, Hellot MF, et al. Magnesium sulfate given before very-preterm birth to protect infant brain: the randomised controlled PREMAG trial*. BJOG. 2007;114:310–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mittendorf R, Dambrosia J, Pryde PG, Lee KS, Gianopoulos JG, Besinger RE, Tomich PG. Association between the use of antenatal magnesium sulfate in preterm labor and adverse health outcomes in infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1111–1118. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rouse DJ, Hirtz DG, Thom E, Varner MW, Spong CY, Mercer BM, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of magnesium sulfate for the prevention of cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:895–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brossard-Racine M, du Plessis AJ, Limperopoulos C. Developmental cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome in ex-preterm survivors following cerebellar injury. Cerebellum. 2015;14:151–164. doi: 10.1007/s12311-014-0597-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merrill JD, Piecuch RE, Fell SC, Barkovich AJ, Goldstein RB. A new pattern of cerebellar hemorrhages in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102:E62. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.6.e62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limperopoulos C, Benson CB, Bassan H, Disalvo DN, Kinnamon DD, Moore M, et al. Cerebellar hemorrhage in the preterm infant: ultrasonographic findings and risk factors. Pediatrics. 2005;116:717–724. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steggerda SJ, Leijser LM, Wiggers-de Bruine FT, van der Grond J, Walther FJ, van Wezel-Meijler G. Cerebellar injury in preterm infants: incidence and findings on US and MR images. Radiology. 2009;252:190–199. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2521081525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steggerda SJ, De Bruine FT, van den Berg-Huysmans AA, Rijken M, Leijser LM, Walther FJ, van Wezel-Meijler G. Small cerebellar hemorrhage in preterm infants: perinatal and postnatal factors and outcome. Cerebellum. 2013;12:794–801. doi: 10.1007/s12311-013-0487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tam EW, Rosenbluth G, Rogers EE, Ferriero DM, Glidden D, Goldstein RB, et al. Cerebellar hemorrhage on magnetic resonance imaging in preterm newborns associated with abnormal neurologic outcome. J Pediatr. 2011;158:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Limperopoulos C, Bassan H, Gauvreau K, Robertson RL, Jr, Sullivan NR, Benson CB, et al. Does cerebellar injury in premature infants contribute to the high prevalence of long-term cognitive, learning, and behavioral disability in survivors? Pediatrics. 2007;120:584–593. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muller H, Beegen B, Schenk JP, Troger J, Linderkamp O. Intracerebellar hemorrhage in premature infants: sonographic detection and outcome. J Perinat Med. 2007;35:67–70. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2007.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zayek MM, Benjamin JT, Maertens P, Trimm RF, Lal CV, Eyal FG. Cerebellar hemorrhage: a major morbidity in extremely preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2012;32:699–704. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim H, Gano D, Ho ML, Guo XM, Unzueta A, Hess C, et al. Hindbrain regional growth in preterm newborns and its impairment in relation to brain injury. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37:678–688. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Limperopoulos C, Chilingaryan G, Guizard N, Robertson RL, du Plessis AJ. Cerebellar injury in the premature infant is associated with impaired growth of specific cerebral regions. Pediatr Res. 2010;68:145–150. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181e1d032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haacke EM, Xu Y, Cheng YCN, Reichenbach JR. Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2004;52:612–618. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller SP, Cozzio CC, Goldstein RB, Ferriero DM, Partridge JC, Vigneron DB, Barkovich AJ. Comparing the diagnosis of white matter injury in premature newborns with serial MR imaging and transfontanel ultrasonography findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1661–1669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92:529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouse DJ, Landon M, Leveno KJ, Leindecker S, Varner MW, Caritis SN, et al. The Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units cesarean registry: chorioamnionitis at term and its duration-relationship to outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kliegman RM, Hack M, Jones P, Fanaroff AA. Epidemiologic study of necrotizing enterocolitis among low-birth-weight infants. Absence of identifiable risk factors. J Pediatr. 1982;100:440–444. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80456-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson KB, Grether JK. Causes of cerebral palsy. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1999;11:487–491. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199912000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galinsky R, Davidson JO, Drury PP, Wassink G, Lear CA, van den Heuji LG, et al. Magnesium sulfate and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular adaptations to asphyxia in preterm fetal sheep. J Physiol. 2016;594:1281–1293. doi: 10.1113/JP270614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burd I, Breen K, Friedman A, Chai J, Elovitz MA. Magnesium sulfate reduces inflammation-associated brain injury in fetal mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald JW, Silverstein FS, Johnston MV. Magnesium reduces N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-mediated brain injury in perinatal rats. Neurosci Lett. 1990;109:234–238. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90569-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion Number 455. Magnesium sulfate before anticipated preterm birth for neuroprotection. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:669–671. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d4ffa5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang JH, Jelin A, Valderramos S, Thiet MP, Zlatnik MG. 490: Magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection in preterm infants: implementation of a new study protocol on labor and delivery, a quality improvement study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:S197. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bickford CD, Magee LA, Mitton C, Kruse M, Synnes AR, Sawchuck D, et al. Magnesium sulphate for fetal neuroprotection: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:527–538. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamrick SEG, Miller SP, Leonard C, Glidden DV, Goldstein R, Ramaswamy V, et al. Trends in severe brain injury and neurodevelopmental outcome in premature newborn infants: the role of cystic periventricular leukomalacia. J Pediatr. 2004;145:593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gano D, Andersen SK, Partridge CP, Bonifacio SL, Xu D, Glidden DV, et al. Diminished white matter injury over time in a cohort of premature newborns. J Pediatr. 2015;166:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volpe JJ. Cerebellum of the premature infant: rapidly developing, vulnerable, clinically important. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:1084–1104. doi: 10.1177/0883073809338067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Limperopoulos C, Chilingaryan G, Sullivan N, Guizard N, Robertson RL, du Plessis AJ. Injury to the premature cerebellum: outcome in relation to remote cortical development. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24:728–736. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]