Abstract

Rationale

Renal inflammation contributes to the pathophysiology of hypertension. CD161a+ immune cells are dominant in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat (SHR) and expand in response to nicotinic cholinergic activation.

Objective

We aimed to phenotype CD161a+ immune cells in pre-hypertensive SHR following cholinergic activation with nicotine, and determine if these cells are involved in renal inflammation and the development of hypertension.

Methods and Results

Studies utilized young SHR and Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. Splenocytes and bone marrow cells were exposed to nicotine ex-vivo and nicotine was infused in-vivo. Blood pressures, kidney, serum, and urine were obtained. Flow cytometry, Luminex/ELISA, immunohistochemistry, confocal microscopy, and Western blot were used. Nicotinic cholinergic activation induced proliferation of CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages in SHR-derived splenocytes, their renal infiltration, and premature hypertension in SHR. These changes were associated with increased renal expression of monocyte-chemoattractant-protein-1 (MCP-1) and very-late-antigen-4 (VLA-4). Lectin-Like-Transcript 1 (LLT1), the ligand for CD161a, was overexpressed in SHR kidney, while vascular cellular (VCAM-1) and intracellular adhesion molecules (ICAM-1) were similar to WKY. Inflammatory cytokines were elevated in SHR kidney and urine following nicotine infusion. Nicotine mediated renal macrophage infiltration/inflammation was enhanced in denervated kidneys, not explained by angiotensin-II levels or expression of angiotensin type-1/2 receptors. Moreover, expression of the anti-inflammatory α7-nicotinic-acetylcholine receptor was similar in young SHR and WKY.

Conclusions

A novel, inherited nicotinic cholinergic inflammatory effect exists in young SHR, measured by expansion of CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages. This leads to renal inflammation and premature hypertension, which may be partially explained by increased renal expression of LLT-1, MCP-1, and VLA-4.

Keywords: Hypertension, renal, integrin, macrophage, lectin, CD68, nicotine, innate immunity, inflammation, CD161, cholinergic, SHR

Subject Terms: Hypertension, Inflammation, Autonomic Nervous System

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is a multifaceted disease with many contributing factors. These factors can be categorized into renal, neural, vascular, and immune mechanisms. Classically, elevated sympathetic activity has been thought to contribute to the development of hypertension via direct vascular effects, activation of the renin-angiotensin-system (RAS), and increased sodium retention1–3. Likewise, inflammatory mechanisms play a role in the development of hypertension 4. Angiotensin II’s (Ang II) pro-inflammatory effects were believed to be sufficient to explain the inflammation that accompanies the development of hypertension5–7.

The concept of an anatomic and physiologic interaction between the nervous and immune systems has been documented8,9. A major advance in the field was the discovery of the “cholinergic anti-inflammatory reflex”, which demonstrated that vagal stimulation and cholinergic stimulation with nicotine could suppress the immune response in animal models of sepsis, translating to a mortality benefit10. The immunosuppressive effects of nicotinic cholinergic activation were found to be mediated by the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α 7-nAChR)11. Interestingly, nicotinic receptors have also been shown to trigger inflammation 12. Our lab has previously shown that cholinergic activation of splenocytes derived from normotensive WKY rats was anti-inflammatory whereas activation of splenocytes from pre-hypertensive SHR with nicotine led to an abnormally exaggerated innate inflammatory immune response to TLR activation, as measured by increases in both IL-6 and IL-1β 13. The anti-inflammatory effect in the WKY was blocked by α–bungarotoxin, a blocker of α7-nAChR. Thus, nicotinic cholinergic activation can induce “anti-inflammatory” or “inflammatory” pathways. An imbalance in these pathways could tilt the balance towards excessive inflammation.

There was also an abnormal prevalence and expansion of a CD161a+ immune cell in the splenocytes of young pre-hypertensive SHR, but not the WKY 13. These results suggested that nicotine’s abnormal and paradoxical pro-inflammatory modulation of the CD161a+ immune cell may play a role in the development of hypertension in the SHR.

CD161a was first identified as a marker in human natural killer (NK) cells 14, a member of the lectin-like receptor subfamily B, member 1 (NKR-P1a). It is a type II transmembrane C-type lectin that is a member of the NKR-P1 family. CD161a is present as a homodimer and can also be detected on antigen presenting cells (APCs; dendritic cells and monocytes/macrophages) and effector immune cells (natural killer and some T-cells) 15. Lectin-Like-Transcript-1 (LLT1), another member of the family, was recently, identified as a ligand for CD161a. This interaction may play a key role in immunomodulatory functions of Th17 cells, as well as NK and NK T-cells16. Given that monocytes/macrophages are known to play an inflammatory role in cardiovascular disease and CD161a+/CD68+ monocytes also play a role in renal transplant rejection we hypothesized that the expanded CD161a+ immune cell population with nicotine consists of activated monocytes/macrophages and is involved in renal inflammation in the SHR 15,17.

The aims of the present study were to 1) characterize the phenotype of CD161a immune cells in the pre-hypertensive SHR, 2) test the hypothesis that they are prevalent in the bone marrow of SHR, thus defining their genetic hematopoietic origin, 3) determine whether nicotinic cholinergic activation expands that population selectively in the SHR and provokes its renal infiltration, thus contributing an inflammatory renal component to the hypertensive state of the young prehypertensive SHR. We then tested the dependence of renal migration of immune cells with nicotine on renal innervation, angiotensin II and nicotinic cholinergic receptors and defined molecular determinants of this migration and renal inflammation.

METHODS

Please see Online Supplemental Materials for detailed “Materials and Methods.

Animals

Male Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and Spontaneous Hypertensive Rats (SHR) [Charles River Laboratories] were used at 3–5 weeks of age. Blood pressures were measured approximately twice per week via tail-cuff.

Splenocyte and bone marrow isolation and culture

Splenocytes and bone marrow (BM) cells were isolated, washed, and re-suspended in plain or complete RPMI (10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 0.1mM non-essential amino acids, 0.1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM Hepes buffer, 100 μg penicillin/streptomycin, 0.2mM glutamine). Cultures were maintained for 48 hours in the presence or absence of nicotine (10μM).

In vivo studies

Subcutaneous (SC) osmotic pumps (Alzet model #2001D or 2002) were implanted in rats anesthetized under isoflurane and rats were infused with either saline or nicotine bitartrate salt (15 mg/kg/day) for 24 hours or 2 weeks. Nicotine bitartrate salt (nicotine) at the current dose is equivalent to approximately 4mg/kg/day of nicotine base18. Tissues, splenocytes, bone marrow cells, serum and urine were collected for further analysis. Cells were analyzed with flow cytometry, tissues with immunohistochemistry/immunofluorescence, and Luminex assays were used to assess serum, urine, and renal homogenates.

Flow cytometry

Splenocytes and BM cells were stained with monoclonal antibodies against rat CD3, CD68 (ED1) CD103, or CD161a. For each acquisition, a minimum of 100,000 events were recorded. Cellular debris and necrotic/non-viable cells were excluded by gating.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

CD68 immunohistochemistry was performed similar to previous work 19. Immunofluorescence was conducted on air dried freshly frozen tissue sections. Sections were exposed to mouse anti-rat CD68 and anti-mouse Alexa fluor 555-labeled antibody was used for secondary detection. Tissue sections were exposed to mouse anti-rat CD161a-FITC monoclonal antibody.

Cytokines, markers of renal inflammation, Norepinephrine, and Ang II

Serum, renal tissue homogenate, and urine were obtained. Renal tissues were homogenized. Using a Luminex assay, serum, renal homogenate, and urine were tested for the presence of inflammatory cytokines (Bio-Rad, catalog# 171k1001m) and/or markers of renal damage (Bio-Rad, catalog# LRK000). Serum and renal homogenates were assessed for Ang II by ELISA (Enzo Lifesciences, catalog #25-0736). Norepinephrine was assessed in renal homogenates by competitive binding ELISA (Eagle Biosciences, catalog# NOU39-K010). Kits were used according to manufacturer instructions.

Western blot

Spleen and kidney tissues were homogenized using a RIPA buffer (Abcam, catalog#156034) and protein concentrations determined using a bicinchoninic protein assay (Pierce). SDS-PAGE electrophoresis was conducted with 4–20% gradient polyacrylamide gels. Membranes were exposed to antibodies targeted against GAPDH, Very-Late Antigen -4 (VLA-4), Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1), LLT1, Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1), Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 (ICAM-1), α7nAChR, Angiotensin II receptor-Type 1 (AT1R), and Angiotensin II receptor-Type 2 (AT2R). Signal detection was accomplished using Amersham™ECL™Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Lifesciences, product # RPN2236).

Unilateral renal denervation

Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and provided analgesia. The left and right renal arteries were directly visualized through a flank incision. Mechanical disruption of the left renal nerve/renal adventitia was completed along with painting of the renal artery with 20% phenol solution.

Nicotinic and angiotensin receptor expression

Western blot was conducted on spleen and kidney tissue for α7nAChR and kidney tissue for AT1R and AT2R as described above.

Statistics

When comparing WKY and SHR directly, two-way ANOVA was used in comparing the effects of nicotine treatment between the two strains. Unpaired t-test was used when comparing effects of treatments within a single-strain, and blood-pressure was compared using two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Prevalence of CD161a+ immune cells in splenocytes and bone marrow of pre-hypertensive SHR and their expansion in vivo with nicotinic cholinergic activation

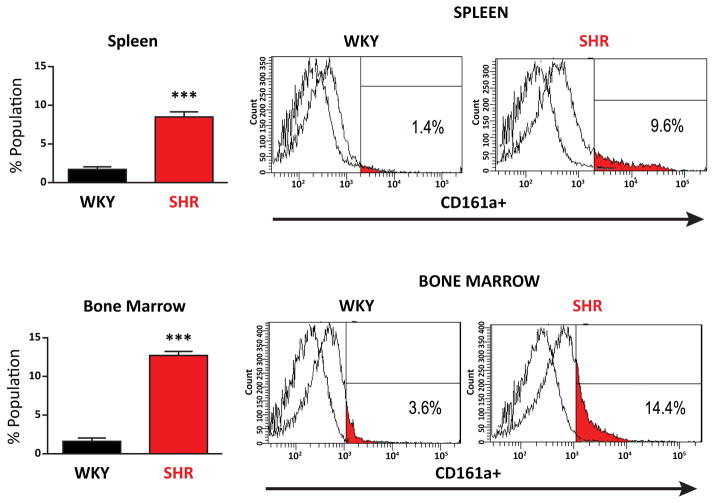

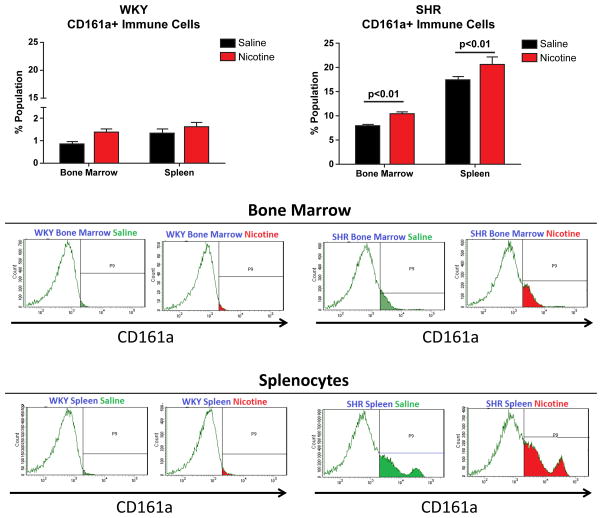

CD161a+ immune cells are significantly more prevalent in, both, the BM (p <0.001) and splenocytes (p<0.001) of the young SHR, compared to the age-matched WKY controls (Figures 1 and 2). Results were obtained gating on CD3− cells to remove the contribution of T-cells, which comprised less than 1% of the total CD161a+ immune cell population and dendritic cells (CD103+) which were less than 0.2% of the total cells. In vivo, over a 2 week period of infusion of nicotine there was significant expansion of CD161a+ immune cells in both the BM and spleen of SHR and the increases with nicotine were significantly greater in the spleen than in the BM (Figure 2). Corresponding increase with either saline or nicotine in the age-matched WKY were negligible and never exceeded 2%.

Figure 1. Spleen and Bone Marrow of Young Pre-Hypertensive SHR have a Prevalent CD161a+ Immune Cell population that is Primarily CD68−.

Spleen and bone marrow cells were isolated from young (3–5 week old) WKY (n=7) and SHR (n=7). Flow cytometry was performed on isolated cells for the presence of CD161a+ immune cells. Upper panel represents splenocytes and lower panel represents bone marrow cells. CD161a+ immune cells in the spleen and bone marrow of the young SHR (red bars) are compared to WKY (gray bars). Representative histogram plots are presented in the panels to the right. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM) and ***= p<0.001.

Figure 2. Nicotine Infusion for 2 Weeks Induces Expansion of CD161a+ Immune Cells in the SHR In Vivo.

Young (3–4 week old) WKY (n=12) and SHR (n=12) were implanted with osmotic pumps infusing either saline (black bars, n=6) or nicotine (15mg/kg/day) (red bars, n=6) for 2 weeks (A). Cells were isolated from the spleens and bone marrow and flow cytometry was performed to assess the presence of CD161a+ immune cells. Nicotine induced proliferation of CD161a+ immune cells in vivo in the bone marrow of the SHR and WKY. The most prominent increase was in splenocytes of SHR with nicotine. Results were compared using two-way ANOVA. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) and p-values as indicated.

Ex-vivo nicotinic cholinergic expansion of CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages in prehypertensive SHR

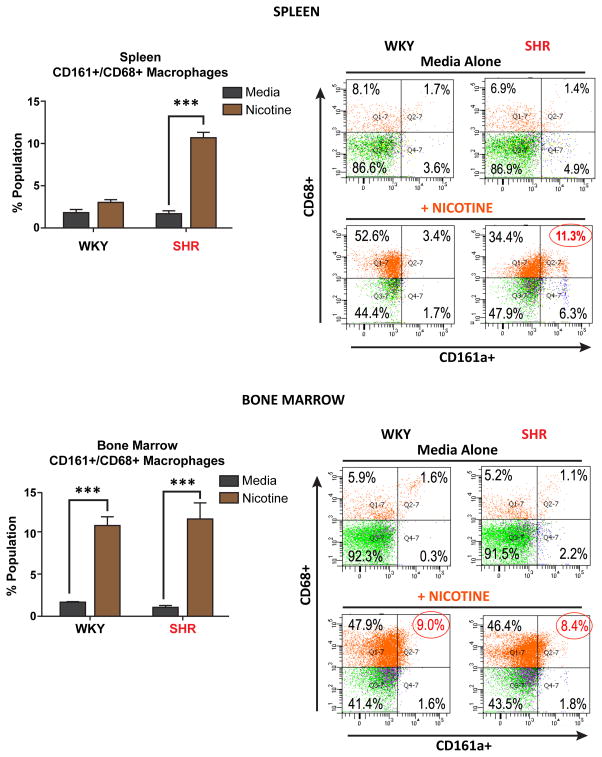

The majority (85–95%) of immune cells in both the BM and spleen of young (3–5 week old) WKY and SHR are CD161a− and CD68− (Figure 3) (upper panels). The exposure of these cells in culture for 48 hours to nicotine resulted in two major phenotypic changes. The first was the acquisition of the CD68 macrophage marker by nearly 50% of splenocytes and BM cells of both, WKY and SHR, while remaining CD161a−. The phenotype of this large CD161a−/CD68+ macrophage population is unclear functionally.

Figure 3. Nicotine Selectively Induces Ex-vivo Expansion of CD68+ Macrophages in Splenocytes of Young SHR.

Splenocyte and bone marrow cells were isolated from 3–5 week old WKY (n=4) and SHR (n=4) cultured in the presence or absence of nicotine for 48 hours and analyzed by flow cytometry, staining for CD161a and CD68. Nicotine (orange bars) induces the proliferation of CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages in young SHR derived splenocytes (Upper Panel) and bone marrow cells (Lower Panels) of both WKY and SHR. Representative histogram plots are presented in the panels to the right. Results were compared using two-way ANOVA. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM) and ***= p<0.001.

The second and, we believe, more meaningful pro-inflammatory effect of nicotine was the acquisition of both CD161a and CD68 markers by approximately 10% of BM cells from both WKY and SHR and by 10% of SHR, but not WKY, derived splenocytes (Figure 3, lower panels). Thus, ex-vivo nicotine exerts a pro-inflammatory response with increased CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages in the central (i.e. BM) immune compartment of both the SHR and WKY; however, the change that is unique to the SHR is the expansion of the CD161a+/CD68+ macrophage subpopulation only in the peripheral immune compartment (i.e. splenocytes) of the SHR. The ex-vivo effect of nicotine on BM cells of WKY was not observed in vivo. However, the pronounced ex-vivo effect on SHR splenocytes was prominent in vivo with significantly larger increases than seen in the BM, particularly after nicotine (Figure 2).

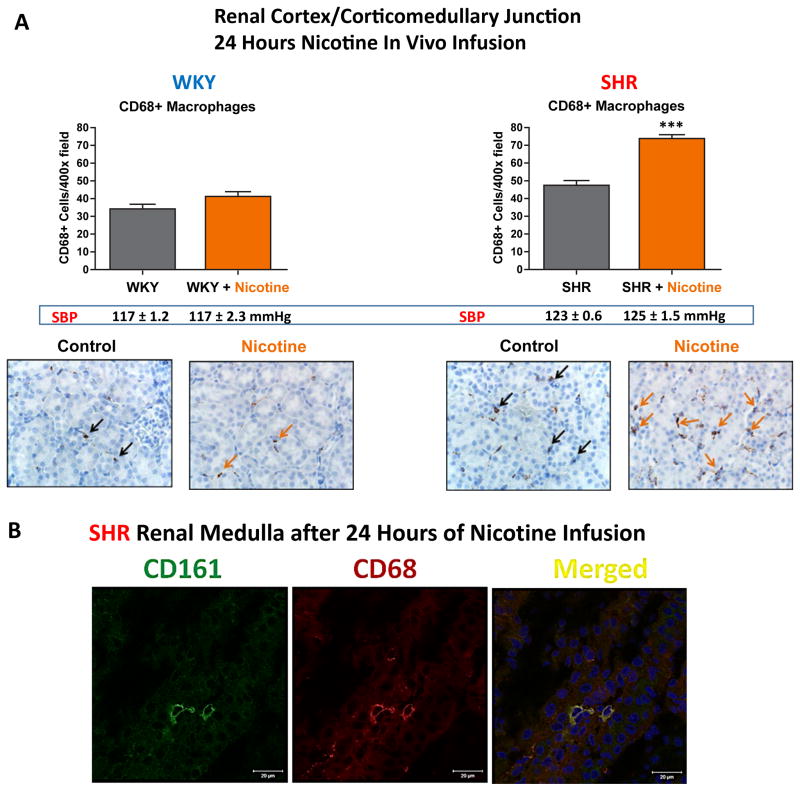

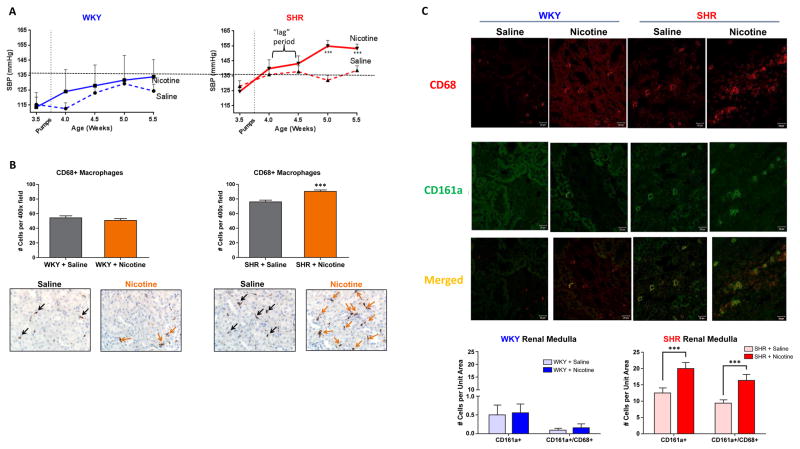

Nicotinic cholinergic activation induces renal infiltration of CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages in pre-hypertensive SHR as early as 24 hours

Given the ability of nicotine to induce expansion of the CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages selectively in young-SHR splenocytes, we asked whether the in vivo administration of nicotine induced renal infiltration of the CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages in the young SHR. Following 24 hours of subcutaneous administration of nicotine (15mg/kg/day), there was an increase in the number of CD68+ macrophages within the renal cortex and corticomedullary junction of the young SHR that was not seen in the age-matched WKY controls (Figure 4A) (p<0.001). Co-localization of CD161a with CD68 could also be seen in macrophages infiltrating the renal medulla (Figure 4B). Blood pressure measurement after nicotine infusion for 24 hours showed no increase in either the young WKY or SHR, compared to saline controls (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. 24 Hour Nicotine Infusion in vivo Induces CD161a+/CD68+ Macrophage Infiltration in Renal Medulla.

Young (3–5 week old) WKY (n=6) and SHR (n=6) were implanted with osmotic pumps infusing either saline (n=3, each strain) or nicotine (15mg/kg/day) (n=3, each strain) for 24 hours. (A) In vivo cholinergic activation with subcutaneous nicotine (orange bars) induces expansion/infiltration of CD68+ macrophages in the renal cortex/corticomedullary junction (black and orange arrows) in the pre-hypertensive SHR, but not WKY, compared to saline infusion (grey bars). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) of each corresponding group is listed under bar graphs and shows that there were no significant differences in (SBP) between groups. (B) Confocal images of two cells in the renal medulla showing co-localization of CD161a and CD68. Images shown are 63x (40x images are shown in Figure 5C) demonstrate co-localization of CD161 and CD68. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). *** = p<0.001, based on two-way ANOVA.

Nicotine infusion for 2 weeks induces premature hypertension and continued infiltration of CD161a+/68+ macrophages into the renal medulla in young SHR

Nicotine infusion for 2 weeks significantly raised the systolic blood pressure (SBP) in young SHR from 124 ± 3 mmHg to 154 ± 3mmHg (p < 0.003, n=10), while no significant increase in SBP was noted in the saline infused SHR (n=10) (Figure 5A). Interestingly, the rise in pressure noted in nicotine-infused young SHR occurred into the second week of infusion, following a 3–5 day “lag period”. In contrast, nicotine infusion had no effect on the SBP of the WKY (Figure 5A). The induction of premature hypertension in response to nicotine infusion in vivo for 2 weeks correlated with a continued infiltration of CD68+ macrophages in the renal cortex and corticomedullary junction of young pre-hypertensive SHR compared to age-matched WKY controls (Figure 5B). Confocal microscopy confirmed continued increase in infiltration of CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages into the SHR renal medulla (Figure 5C). The presence of CD3+ T-cells was negligible in the renal cortex or medulla (data not shown).

Figure 5. 2 Week Nicotine Infusion Induces Pre-mature Development of Hypertension in Pre-Hypertensive SHR and Persistent Increase in Renal Medulla CD161a+/CD68+ Macrophage Infiltration.

Young (3–4 week old) WKY and SHR were implanted with osmotic pumps infusing either saline (dashed-lines, n=10, each strain) or nicotine (15mg/kg/day) (solid-lines, n=10, each strain). Blood pressure was monitored by tail-cuff over the course of 2 weeks (A). Renal cortex/corticomedullary junction were harvested at termination and stained for CD68 for immunohistochemistry (B). Renal medulla was also stained with CD68 (red) and CD161a (green) and confocal microscopy (C) was performed to determine whether CD68+ renal macrophages co-expressed CD161a. In vivo cholinergic activation with subcutaneous nicotine induces early development of hypertension in the SHR, compared to SHR with saline and WKY with either saline or nicotine. Nicotine infusion led to a significant increase in CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages in renal tissues of young nicotine infused SHR. Images are 40x of the renal medulla. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). *** = p<0.003, based on two-way ANOVA.

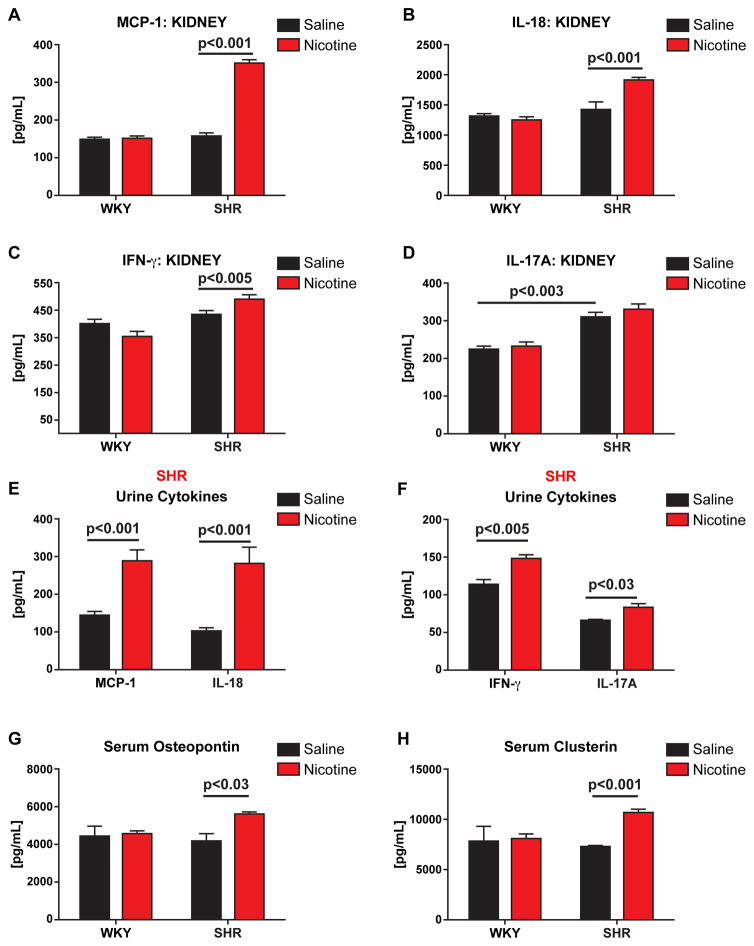

Renal inflammation with nicotinic cholinergic activation in SHR

Following infusion of nicotine for 2 weeks, there were significant elevations of MCP-1, IL-18, and IFN-gamma in the kidney in young SHR, compared with saline (Figure 6A–C). We also noted a significant increase in renal homogenates of IL-17a of saline and nicotine infused SHR, compared to WKY controls (Figure 6D). Urinary levels of MCP-1, IL-18, and IFN-γ paralleled levels in renal homogenates (Figures 6E&F). Serum levels of osteopontin (OPN) (p<0.03) and clusterin (p<0.001), well documented markers of renal cellular damage20, were also significantly elevated in SHR (Figure 6G and 6H, respectively).

Figure 6. Chronic Nicotine Infusion Induces Renal Inflammation.

Young (3–5 week old) WKY (n=8) and SHR (n=8) were implanted with osmotic pumps infusing either saline (n=4) or nicotine (15mg/kg/day) (n=4) 2 weeks. After infusions were complete, renal homogenates (A–D), serum (G & H) collected, and urine (E & F) collected. MCP-1 (A & E), IL-18 (B & E), IFN-g (C & F), IL-17a (D & F), Osteopontin (G), and Clusterin (H) were measured by Luminex assay. P-values as indicated based on two-way ANOVA. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). *** = p<0.003, based on two-way ANOVA.

The presence of renal inflammation and systemic activation of adaptive immune responses is supported by significantly elevated urinary cytokines, including Regulated on Activation-Normal T-Cell Expressed and Secreted (RANTES) (Online Figures I, II, and III). Thus, nicotine mediated renal inflammation was pronounced with increased infiltration of the CD161a+/CD68+ inflammatory macrophages in the young pre-hypertensive SHR renal medulla.

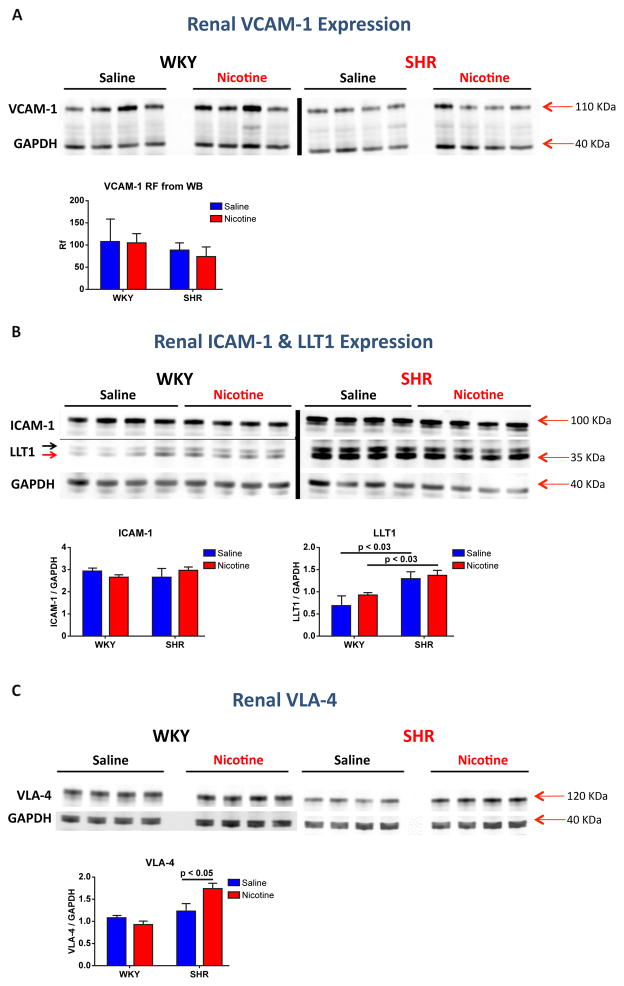

Mediators of renal macrophage migration

Although nicotine mediated renal macrophage infiltration leads to renal damage, it was not clear why the CD161a+/CD68+ immune cells hone to the kidney. Based on reports that nicotine led to enhanced vascular-cell-adhesion-molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intracellular-adhesion-molecule (ICAM-1) expression 21,22 and the fact that CD161a+ is a receptor for lectin-like-transcript 1 (LLT1), it was important to ask whether nicotine increased expression of these immune cell adhesion molecules in the kidney of young SHR. There was no increase in VCAM-1 or ICAM-1 expression by Western blot in renal homogenates of young nicotine infused SHR or WKY, compared to saline infusion (Figure 7A &6B). However, there was an increase in the expression of very-late-antigen-4 (VLA-4, the immune cell ligand for VCAM-1) in renal homogenates of nicotine infused SHR (Figure 7C) (p< 0.05). LLT1 expression was significantly increased in renal homogenates of saline infused SHR, compared to WKY (p<0.03) (Figure 7B) and there was no further increase in LLT1 expression in nicotine infused SHR, compared to saline infusion.

Figure 7. Effect of Chronic Nicotine Infusion on Renal VCAM-1, ICAM-1, LLT1, and VLA-4 Expression in SHR vs WKY.

Young (3 week old) WKY (A, n=8) and SHR (B, n=8) were implanted with osmotic pumps infusing either saline (n=4) or nicotine (15mg/kg/day) (n=4) at 3–4 weeks of age. After 2 weeks of infusion, expression of VCAM-1 (A), ICAM-1 & LLT1 (B), and VLA-4 (C) were assessed by Western blot in renal homogenates. Western blot for LLT1 detected the glycosylated (B, black arrow) and the deglycosylated (B, red arrow) form of LLT1. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) and p-values as indicated, based on two-way ANOVA.

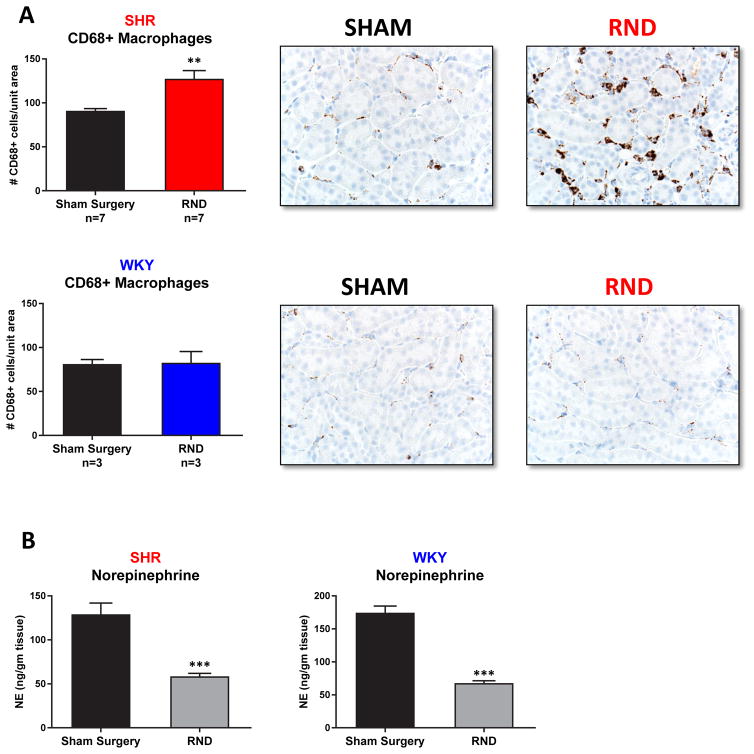

Renal denervation enhances nicotine-mediated renal macrophage infiltration

Nicotine can increase central sympathetic outflow and increased renal sympathetic nerve activity has been reported to possibly play a role in renal inflammation23,24. Based on this, we asked whether renal sympathetic innervation played a role in nicotine-mediated renal macrophage infiltration. Denervated kidneys in young (3–5 week) SHR actually demonstrated an approximately 35% increase in macrophage infiltration following 24 hours of nicotine infusion, compared to the sham-treated contralateral kidneys in the same animal (Figure 8) (p<0.001). Adequate renal denervation was confirmed by norepinephrine (NE) analysis, which demonstrated an approximately 65% decrease in NE in the denervated kidney (Figure 8) (p<0.001).

Figure 8. Effect of Unilateral Renal Denervation (RND) on Nicotine Mediated Renal Inflammation and Norepinephrine levels.

Young (3 week old) SHR (n=7) and WKY (n=3) underwent unilateral renal denervation followed by 24 hour nicotine (15mg/kg/day) infusion via subcutaneous osmotic pumps. After infusion, kidneys were harvested and analyzed by immunohistochemistry for the presence of CD68+ macrophages in renal cortex/corticomedullary junction (A). Representative fields of view are presented in the panels to the right. (B) Norepinephrine (NE) levels were reduced significantly in the denervated kidney. NE levels were assessed by ELISA in the kidney that underwent Sham surgery vs Renal Denervation. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). ** = p<0.01 and *** = p<0.001.

Nicotine does not induce changes in Angiotensin II or Angiotensin receptors

Levels of angiotensin II (Ang II) and angiotensin AT1 and AT2 receptors were assessed in serum and kidneys of saline and nicotine infused SHR. There was no increase in Ang II levels in the serum or kidney of nicotine infused SHR, compared to saline controls (Online Figure IV). However, circulating levels of Ang II were elevated in SHR when compared to age-matched WKY controls (Online Figure IV) (p<.001). There was also no difference in expression of the AT1R or AT2R in the kidneys of nicotine infused SHR, compared to saline controls.

α7-nAChR expression does not differ in spleen or kidney of young SHR

α7-nAChR has been documented to mediate an anti-inflammatory effect in various models. Although no difference was noted in α7-nAChR expression in young pre-hypertensive SHR, α7-nAChR expression was decreased in 40 week old hypertensive SHR. As a result, we analyzed the expression of α7-nAChR in the spleen and kidney of young pre-hypertensive SHR to determine if decreased expression of this receptor may explain the increased inflammation we find in the SHR in response to nicotinic cholinergic activation. Consistent with previously reported findings25, we found no difference in the expression of α7-nAChR in the spleen of 3–4 week old SHR when compared to age-matched WKY controls (Online Figure V-A). There was also no difference in the expression of α7-nAChR in the renal homogenates of young SHR, compared to WKY (Online Figure V-A). Chronic nicotine infusion also had no effect on the expression of α7-nAChR in the young pre-hypertensive SHR or age-matched WKY (Online Figure V-B). Thus, a reduced expression of α7-nAChR may not explain the pro-inflammatory and pro-hypertensive effect of nicotinic cholinergic activation in the young SHR. It might, however, sustain the elevated blood pressure once hypertension has developed.

DISCUSSION

The central finding of the current study is that an abnormal population of CD161a+ immune cells harbors a significant pro-inflammatory sensitivity to nicotinic cholinergic activation. This is evidenced by activation and expansion of a CD161a+/CD68+ monocyte/macrophage population in vitro and in vivo, renal infiltration of these macrophages, and the development of hypertension prematurely in young SHR. These CD161a+ immune cells are prevalent in the bone marrow and spleen of the pre-hypertensive SHR, suggesting a genetic/hematopoietic abnormality is responsible for this abnormal inflammation. Increased expression of LLT1 (the specific ligand for CD161a), MCP-1, and VLA-4 explain the increased renal infiltration of these CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages, and the presence of increased renal inflammation. We found no evidence that Ang II, AT1R and AT2R, and α7-nAChR were altered during nicotinic cholinergic activation and, thus, would not explain the proinflammatory response in SHR. Nor did renal denervation reduce the renal macrophage infiltration during the nicotinic cholinergic stimulation in SHR.

The evidence that nicotinic cholinergic activation may induce the development of hypertension in normotensive individuals or in wild-type animal models used as normotensive controls has been debatable26,27. On the other hand, pre-hypertensive SHR have been shown to develop premature hypertension 26,28 and oxidative stress following chronic nicotine administration 26. Our results are consistent with studies demonstrating nicotine mediated premature development of hypertension and extend the findings of previous studies by demonstrating a cholinergic mediated pro-inflammatory mechanism that appears to contribute to hypertension in this model.

Cholinergic influence on the immune system

When the “Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Reflex” was discovered, the proposed mechanistic explanation was elusive given the presumed lack of parasympathetic nerve fibers into the spleen. However, it was later shown that vagal stimulation indirectly triggered the release of acetylcholine from post-synaptic splenic T-cells that were activated by norepinephrine at the nerve terminals of the splenic nerve29. These studies advanced our understanding of mechanisms that underlie the neural regulation of immune responses – combining direct innervation and indirect regulation via paracrine secretion of acetylcholine. Essential to understanding the complexity of the ‘neuro-immuno’ axis is the concept of the neuronal and non-neuronal cholinergic influence on the immune system. The current work demonstrates that the cholinergic influence is through nicotinic cholinergic receptor activation of immune cells and, being ex vivo, can be characterized as non-neuronal. It is likely, as demonstrated in this manuscript, that a combination of direct and indirect neural influences on immune cells are operating to define immune responses.

Anti- and pro-inflammatory effects of nicotinic cholinergic activation

The relationship of nicotine with the immune system is dual faceted. In both mice and rats, nicotine has been described as having anti-inflammatory properties30. Other reports have documented nicotine’s ability to mediate pro-inflammatory effects at a range of doses11,13,31. The nature of the response to nicotine does not appear to be dose-dependent, but rather a reflection of the pathologic inflammatory state of the SHR. In vivo and in vitro doses of nicotine bitartrate have anti-inflammatory effects in the WKY, confirming earlier reports by other investigators 9 and our group 13, while the same doses simultaneously exert a pro-inflammatory effect in the pre-hypertensive SHR, as manifested by the expansion of the CD161a+/CD68+ macrophage. Interestingly, we noted ex-vivo expansion of CD161+/CD68+ macrophages in bone marrow and splenocytes of young SHR but only in the bone marrow of WKY in cultures with exposure to nicotine for 48 hours (Figure 3). The possibility exists that, post-nataly, the very young WKY and SHR harbor a proinflammatory potential unmasked by ex-vivo nicotine. This propensity may be selectively suppressed in WKY, but not in SHR and fails to extend to the peripheral immune system over the 2-week period during the in vivo nicotine infusion (Figure 2). During that time-span we noted the CD68+ macrophages increased significantly in the kidneys of SHR but not WKY (Figure 5) and the blood pressure of SHR increased prematurely in the prehypertensive phase; whereas, the WKY remained normotensive (Figure 5). Alternatively, an anti-inflammatory neurohumoral influence of nicotine infusion in vivo may be selectively effective in suppressing the ex-vivo proliferation seen in WKY bone marrow, but not in SHR where the neurohumoral influence may be conversely pro-inflammatory.

In our earlier study13, the anti-inflammatory effect of nicotine in WKY and its proinflammatory effect in SHR were only seen in the inflammatory cytokine response following activation of the innate immune response with TLRs, but nicotine alone had no direct effect on secretion of cytokines ex vivo in WKY or SHR splenocytes. That study, similar to those of Li et al and Borovikova et al, highlights the importance of the interaction between the innate immune pathways and nicotinic cholinergic pathways.

Studies reporting the pro-hypertensive effects of nicotine selectively in young pre-hypertensive SHR, using WKY as controls, have used subcutaneous nicotine pellets that delivered higher concentrations of nicotine base (up to 25mg/kg/day) than the current study 26,28. Moreover, higher doses of nicotine base showed selective induction of reactive oxidation/inflammation and enhanced pressor response in SHR, and no inflammatory or hemodynamic effects were seen in normotensive WKY 26. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of nicotine inducing expansion of, both, the CD161a+/CD68+ and CD161a−/CD68+ macrophage populations in the pre-hypertensive SHR. We conclude that, although cholinergic stimulation has anti-inflammatory effects at the current doses of nicotine in the normotensive WKY, there exists an abnormal cholinergic pro-inflammatory effect in SHR.

Role of nicotinic cholinergic receptors in immunomodulation

The anti-inflammatory effects of nicotine have been attributed to the activation of the α7-nAChR 11 and, more recently, to the alpha-4/beta-2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors32. Hence, it is possible that differential reduction in the expression of anti-inflammatory nicotinic receptors in the SHR vs. WKY could contribute to the inflammatory effects of nicotine observed in SHR. α7-nAChR has been shown to be equally expressed by Western blot in the splenocytes of young SHR, compared to age-matched WKY25, but decreased with advanced age and the development of hypertension25. The decreased expression of α7-nAChR with the development of hypertension and advanced age may be more likely sustaining hypertension than causing it. This is supported by the studies of Ferrari et al that showed that decreased cell surface expression of α7-nAChR in hypertensive stroke prone SHR (spSHR) was restored with normalization of blood pressure 33. Our current manuscript is similar to Li et al, in that we confirm the comparable expression of α7-nAChR between the young WKY and SHR, but we also show that nicotinic cholinergic activation induced the development of premature hypertension and inflammatory changes without changing the level of expression of the α7-nAChR in the kidney. Thus, the nicotinic cholinergic mediated inflammatory response in the SHR cannot be explained on the basis of decreased expression of the anti-inflammatory α7-nAChR.

The subunit composition of the pro-inflammatory nicotinic receptor in SHR will require further studies. The challenge in using pharmacologic blockers is in the lack of specificity of the blockers and the large number of subunits and their various heteromeric and homomeric combinations that form a large number of different nicotinic receptors in various tissues including the nervous system, skeletal muscle, and immune cells. In our previous work13, we reported the effect of pharmacologic blockade with α-bungarotoxin, known to have a greater affinity for α7-nAChR. In those experiments we had observed that nicotine suppressed the IL-6 release from WKY splenocytes caused by TLR activation and conversely enhanced significantly the IL-6 release from SHR splenocytes. Alpha-bungarotoxin prevented the decline in IL-6 release in WKY and did not alter the enhanced IL-6 release in SHR. Thus the anti-inflammatory response to nicotine was dependent on the α7-nAChR, but the pro-inflammatory response was not.

Effect of activation or deletion of α7nAChR

The relationship between α7-nAChR expression and hypertension was tested in 2 other experiments reported by Li et al (25). One was in α7-nAChR −/− mice rendered hypertensive by clipping 1 renal artery. Within 8 weeks of surgery the magnitude of increase in systolic blood pressure was similar in WT and α7-nAChR −/− despite an increase in cytokine levels in the KO mice.

A second experiment was the use of PNU 282987 the agonist of α7 receptors in 40 week old hypertensive SHR. The acute intravenous use of the agonist had no effect on arterial pressure or heart rate nor did the chronic administration of PNU for 28 days. Although there was no reduction in blood pressure there were decreases in several inflammatory cytokines and significant attenuation of end-organ damage. Clearly α7-nAChR mediates an important anti-inflammatory influence and its absence exacerbates the end-organ damage by hypertension without influencing the level of arterial pressure.

The functional significance of CD161a in the nicotinic cholinergic inflammation

CD161a is inflammatory and activation of this receptor has been shown to increase inflammatory cytokine secretion 34. Our results support an early innate inflammatory role for CD161a+ as a marker of inflammatory immune cells that mature into activated CD68+ macrophages and play a role in renal inflammation. CD3+ (T-cells) and CD103+ (dendritic cells) immune cells comprised <1% and <2% of the total CD161a+ immune cells in the SHR, respectively. Previous studies have identified a role for CD161a+ monocytes/macrophages in renal allograft rejection 15. Our finding that CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages infiltrate the renal parenchyma, suggests that there may be a possible autoimmune response to the “self” kidney. This would be consistent with more recent reports of autoimmunity playing a potential role in the development of hypertension35–37. The elevated levels of IL-17a in the kidney, urine, and serum in the present study support the possible presence of an autoimmune process that may be marked by renal infiltration of these CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages in the early stages.

Mediators of renal inflammation

Renal inflammation is a known mechanism for the development of hypertension in a number of experimental models of hypertension38–40. Data presented here shows an increase in the renal levels of MCP-1, IL-18, and IFN-gamma. These are consistent with previous reports of an increase in the levels of MCP-1 in the SHR, compared to the WKY 41, where MCP-1 is a chemotactic factor for recruitment of CD68+ monocytes/macrophages. IL-18 induces production of IFN-gamma. The recruitment of monocytes and their differentiation into macrophages under cholinergic influence may play a role in the induction or secretion of IL-18 and IFN-gamma. As mentioned above, the significant elevation of IL-17a suggests that the renal inflammation may represent an autoimmune process, such as nephritis. Consistent with an autoimmune T-lymphocyte response, we found significant elevations of RANTES in the urine, kidney, and serum, suggesting that the local innate immune response in the kidney may be associated with activation of a systemic adaptive T-lymphocyte response 42. Macrophage infiltration and the initiation of renal inflammation preceding the development of hypertension is consistent with established models of nephrogenic hypertension.

The role of adhesion molecules in renal inflammation

Despite the fact that expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 have been noted to be increased in the presence of nicotine in other studies43; we found no increase in the renal expression of these adhesion molecules in nicotine-infused SHR. Increased expression of MCP-1 and LLT1, on the other hand, in the kidney of the young SHR, correlate with and may contribute to the selective recruitment of CD161a+/CD68+ immune cells to the kidneys. The role of these cells in the autoimmune reaction to the kidneys is supported by the increased expression of VLA-4 (the ligand for VCAM-1), which plays a causative role in models of nephritis44,45. Not only is the expression of VLA-4 (the ligand for VCAM-1) and VCAM-1 discordant in the current study, but blocking VLA-4 and not VCAM-1, abrogates renal inflammation in models of nephritis, suggesting a VCAM-1 independent mechanism for the inflammation mediated by the presence of VLA-4 44.

Effects of sympathetic activity and Angiotensin II

Despite the fact that nicotine is known to stimulate central and peripheral sympathetic activity, including the adrenal medulla46,47, unilateral renal denervation failed to abrogate the nicotine-mediated inflammation, but, rather, counterintuitively, exaggerated the inflammation. Thus, the pro-inflammatory effects of nicotinic cholinergic activation that we observed appear to result from autocrine/paracrine activation of nicotinic cholinergic receptors on immune cells48. First, the fact that ex-vivo exposure of splenocytes and bone marrow cells to nicotine induced expansion and maturation of the CD161a+/CD68+ inflammatory macrophages independently of innervation argues against the involvement of a neural circuit in the young SHR. Second, the dose of nicotine bitartrate (15mg/kg/day) used was chosen to avoid induction of synthesis and release of adrenal catecholamines from the adrenal medulla, based on previous studies49. Third, immune cells are known to express cholinergic receptors and the enzymatic proteins required for synthesis and secretion of acetylcholine50. Fourth, previous reports failed to identify a cholinergic parasympathetic innervation of the spleen51, hence, paracrine/autocrine effects of cholinergic agents likely play a role in immunomodulation of splenocytes in vivo 29. Finally, since the activation of the RAS pathway is known to activate sympathetic activity and Ang II has been shown by our group to induce pro-inflammatory immune responses13, we looked at the expression of Ang II, AT1R, and AT2R and found no change in the Ang II, AT1R, or AT2R expression in SHR infused with nicotine, compared to those infused with saline.

Relevance to other models of hypertension

The current work is focused on the SHR because of the spontaneous and evolving nature of the rise in pressure over time in this model and its genetic determination which parallel human essential hypertension. The relevance to other models of hypertension is based on the demonstration of an immunological process that involves renal inflammation. The role of the immune system has been documented in various models of hypertension and increased renal macrophage infiltration has also been shown in response to DOCA salt- and AngII-induced hypertension in mice39,40. Hence there is precedence for a similar immunologic process in other models of hypertension. The novel concepts that this model and this study helped us define are 1) the inherent abnormality of the immune system which is an essential component of the pathological state and 2) the proinflammatory contributions of activation of nicotinic cholinergic receptors. Although the importance of drug-induced (Angiotensin or DOCA) and renal or neural models of hypertension is unquestionable, our goal was to investigate the cholinergic mediation of pro-inflammatory and pro-hypertensive effects in a spontaneous genetic model of hypertension. Although a limitation of the SHR rat model is the difficulty of genetic manipulation, we suggest that this mimics the paramount challenge inherent to the complexity of human hypertension that we are trying to model, with its multiple genetic and environmental components.

Significance

The present study specifically identifies an inflammatory CD161a+/CD68+ macrophage population that leads to renal inflammation and the development of hypertension. Where other studies have also shown a hematopoietic basis for the development of hypertension in the SHR model, we specifically identify immune cell mediators involved in this process. The neurohormonal expansion of this immune cell population is a novel inflammatory mechanism that implicates the “neuro-immuno axis” in the development of hypertension, independent of autonomic innervation. This is the first study to document expansion of CD161a−/CD68+ and CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages in response to activation of nicotinic cholinergic receptors. The importance of this pro-inflammatory immune regulation in this model of genetic hypertension is heightened by the simultaneous documentation of its absence in the normotensive WKY control. These data implicate an abnormal cholinergic proinflammatory immune response as a contributing mechanism to the development of renal inflammation and an additional renal component to the genetic hypertension.

The current study also identifies LLT1 (the specific ligand for CD161a) as an important chemotactic factor, along with MCP-1, in the renal parenchyma of the SHR for the selective recruitment of CD161a+/CD68+ M1 phenotype macrophages. Finally, we implicate the expression of VLA-4 as a mediator of the renal damage affected by the macrophages, similar to other models of renal disease. Of additional interest is the lack of evidence that this proinflammatory nicotinic cholinergic activation in SHR is influenced by AngII, AT1 or AT2 receptors, α7nAChR expression, or renal autonomic innervation.

It has become evident that there are several factors that contribute to the link between the autonomic system, the immune system, and hypertension. These include: the dependence of hypertension on, both, the adaptive and innate immune systems; the anti-inflammatory cholinergic reflex noted with efferent vagal nerve stimulation and its mediation by the α7nAChR; the increased sympathetic drive to the BM of SHR, which appears to activate the microglial system in the PVN and induce hypertension; and the abnormalities intrinsic to the immune cells in genetic hypertension that result in a proinflammatory proliferation and migration of macrophages to the kidney upon nicotinic cholinergic activation. The distinctive contribution of this work has focused on the last aspect of these interactions.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Renal inflammation plays a role in the pathogenesis of essential hypertension.

Cholinergic stimulation of immune cells with nicotine exerts an anti-inflammatory suppression of immune responses to toll-like receptor (TLR) activation in normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats.

Paradoxically, cholinergic stimulation enhances the pro-inflammatory cytokine response to TLR activation and expands an inflammatory CD161a+ immune cell population in the pre-hypertensive Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat (SHR).

What New Information Does This Article Contribute

The expanding CD161a+ immune cell population in response to cholinergic activation with nicotine in the pre-hypertensive SHR is characterized as CD68+ macrophages, present in bone marrow, and represents a novel inherited cholinergic abnormality of the innate immune system in genetic hypertension.

Migration of these CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages to the kidney in response to nicotine is independent of renal innervation and associated with enhanced renal cytokine expression and overexpression of the specific ligand for CD161a, lectin-like transcript-1 (LLT1), as well as the development of premature hypertension in the young SHR.

The study documents the expansion of a pro-inflammatory cellular immune response to nicotine in a model of genetic hypertension and implicates an abnormal cholinergic mediation of renal inflammation as a component of genetic hypertension.

The role of the immune system in the development of hypertension is becoming increasingly more evident. Cholinergic regulation of the immune system is known to exert an anti-inflammatory effect. Here we demonstrate and emphasize the importance of the “neuro-immuno axis” as an inflammatory, as opposed to anti-inflammatory, force in the development of genetic hypertension. We show that cholinergic stimulation of splenocytes derived from young pre-hypertensive SHR leads to expansion and differentiation of the inflammatory CD161a+ immune cells into CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages in vitro and in vivo. These inflammatory CD161a+/CD68+ macrophages infiltrate the renal medulla, resulting in renal inflammation and the premature development of hypertension. Identification of the specific ligands of CD161a and CD68 in the renal parenchyma of the SHR explains the migration of these cells to the kidney. These findings highlight the inheritable abnormalities intrinsic to the innate immune system in genetic hypertension that result in proliferation and migration of a unique inflammatory subset of macrophages to the kidney upon nicotinic cholinergic activation. Understanding the proinflammatory influence of cholinergic receptor activation on innate immune responses may represent an opportunity to explore novel therapeutic strategies to treat hypertension.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mike Cicha for assistance in experiments. We would also like to acknowledge Mr. Justin Fishbaugh and the Flow Cytometry Facility staff for use of the equipment and assistance in flow cytometry. Some of the data presented herein were obtained at the Flow Cytometry Facility, which is a Carver College of Medicine/Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center core research facility at the University of Iowa. The Facility is funded through user fees and the generous financial support of the Carver College of Medicine, Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center, and Iowa City Veteran’s Administration Medical Center. We would also like to thank Ms. Angela Hester for her administrative guidance and support.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K08 HL119588, PPG HL14388).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- SHR

spontaneously hypertensive rats

- WKY

Wistar-Kyoto rats

- Ach

Acetylcholine

- Nic

Nicotine

- α7-nAChR

alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- ED1

CD68

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- NK

natural killer cell

- NKRP1

natural killer cell receptor

- LLT1

lectin like transcript 1

- VLA-4

very late antigen 4

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors do not have any disclosures that present a conflict of interest at the time of submission of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Abboud FM. Effects of sodium, angiotensin, and steroids on vascular reactivity in man. Fed Proc. 1974;33:143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abboud FM, Huston JH. Measurement of arterial aging in hypertensive patients. J Clin Invest. 1961;40:1915–1921. doi: 10.1172/JCI104416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobian L, Janecek J, Tomboulian A, Ferreira D. Sodium and potassium in the walls of arterioles in experimental renal hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1961;40:1922–1925. doi: 10.1172/JCI104417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob H, et al. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2010 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai Q, Xu M, Yao M, Sun B. Angiotensin at1 receptor antagonists exert anti-inflammatory effects in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:1042–1048. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoch NE, Guzik TJ, Chen W, et al. Regulation of t-cell function by endogenously produced angiotensin ii. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R208–216. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90521.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller DN, Shagdarsuren E, Park JK, et al. Immunosuppressive treatment protects against angiotensin ii-induced renal damage. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1679–1693. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64445-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felten SY, Olschowka J. Noradrenergic sympathetic innervation of the spleen: Ii. Tyrosine hydroxylase (th)-positive nerve terminals form synapticlike contacts on lymphocytes in the splenic white pulp. J Neurosci Res. 1987;18:37–48. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490180108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nance DM, Sanders VM. Autonomic innervation and regulation of the immune system (1987–2007) Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:736–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature. 2000;405:458–462. doi: 10.1038/35013070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature. 2003;421:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Zhang F, Yang W, Xue S. Nicotine induces pro-inflammatory response in aortic vascular smooth muscle cells through a nfkappab/osteopontin amplification loop-dependent pathway. Inflammation. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10753-011-9324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harwani SC, Chapleau MW, Legge KL, Ballas ZK, Abboud FM. Neurohormonal modulation of the innate immune system is pro-inflammatory in the pre-hypertensive spontaneously hypertensive rat, a genetic model of essential hypertension. Circ Res. 2012;111:1190–1197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.277475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pozo D, Vales-Gomez M, Mavaddat N, Williamson SC, Chisholm SE, Reyburn H. Cd161 (human nkr-p1a) signaling in nk cells involves the activation of acid sphingomyelinase. J Immunol. 2006;176:2397–2406. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiniger B, Stehling O, Scriba A, Grau V. Monocytes in the rat: Phenotype and function during acute allograft rejection. Immunol Rev. 2001;184:38–44. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1840104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamishikiryo J, Fukuhara H, Okabe Y, Kuroki K, Maenaka K. Molecular basis for llt1 protein recognition by human cd161 protein (nkrp1a/klrb1) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:23823–23830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.214254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorffel Y, Latsch C, Stuhlmuller B, et al. Preactivated peripheral blood monocytes in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;34:113–117. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matta SG, Balfour DJ, Benowitz NL, et al. Guidelines on nicotine dose selection for in vivo research. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:269–319. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyerholz DK, Samuel I. Morphologic characterization of early ligation-induced acute pancreatitis in rats. Am J Surg. 2007;194:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaidya VS, Ferguson MA, Bonventre JV. Biomarkers of acute kidney injury. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:463–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ueno H, Pradhan S, Schlessel D, Hirasawa H, Sumpio BE. Nicotine enhances human vascular endothelial cell expression of icam-1 and vcam-1 via protein kinase c, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, nf-kappab, and ap-1. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2006;6:39–50. doi: 10.1385/ct:6:1:39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin HS, Li YJ, Jiang ZA, Liu SY, Guo BY, Wang T. Nicotine-induced icam-1 and vcam-1 expression in mouse cardiac vascular endothelial cell via p38 mapk signaling pathway. Anal Quant Cytopathol Histpathol. 2014;36:258–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ditting T, Veelken R, Hilgers KF. Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptors in hypertensive renal damage: A promising therapeutic target? Hypertension. 2008;52:213–214. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veelken R, Vogel EM, Hilgers K, et al. Autonomic renal denervation ameliorates experimental glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1371–1378. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li DJ, Evans RG, Yang ZW, et al. Dysfunction of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway mediates organ damage in hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:298–307. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bui LM, Keen CL, Dubick MA. Comparative effects of 6-week nicotine treatment on blood pressure and components of the antioxidant system in male spontaneously hypertensive (shr) and normotensive wistar kyoto (wky) rats. Toxicology. 1995;98:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(95)91102-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blann AD, Steele C, McCollum CN. The influence of smoking and of oral and transdermal nicotine on blood pressure, and haematology and coagulation indices. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:1093–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrari MF, Fior-Chadi DR. Chronic nicotine administration. Analysis of the development of hypertension and glutamatergic neurotransmission. Brain Res Bull. 2007;72:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, et al. Acetylcholine-synthesizing t cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science. 2011;334:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1209985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sopori ML, Kozak W, Savage SM, Geng Y, Kluger MJ. Nicotine-induced modulation of t cell function. Implications for inflammation and infection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;437:279–289. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5347-2_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau PP, Li L, Merched AJ, Zhang AL, Ko KW, Chan L. Nicotine induces proinflammatory responses in macrophages and the aorta leading to acceleration of atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor(−/−) mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:143–149. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000193510.19000.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hosur V, Loring RH. Alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptors partially mediate anti-inflammatory effects through janus kinase 2-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 but not calcium or camp signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:167–174. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.066381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrari R, Frasoldati A, Leo G, et al. Changes in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit mrnas and nicotinic binding in spontaneously hypertensive stroke prone rats. Neurosci Lett. 1999;277:169–172. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00879-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arase H, Arase N, Saito T. Interferon gamma production by natural killer (nk) cells and nk1.1+ t cells upon nkr-p1 cross-linking. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2391–2396. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathis KW, Broome HJ, Ryan MJ. Autoimmunity: An underlying factor in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16:424. doi: 10.1007/s11906-014-0424-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathis KW, Wallace K, Flynn ER, Maric-Bilkan C, LaMarca B, Ryan MJ. Preventing autoimmunity protects against the development of hypertension and renal injury. Hypertension. 2014;64:792–800. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Pons H, Quiroz Y, Lanaspa MA, Johnson RJ. Autoimmunity in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:56–62. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dinh QN, Drummond GR, Sobey CG, Chrissobolis S. Roles of inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:406960. doi: 10.1155/2014/406960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson RJ, Alpers CE, Yoshimura A, et al. Renal injury from angiotensin ii-mediated hypertension. Hypertension. 1992;19:464–474. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson RJ, Schreiner GF. Hypothesis: The role of acquired tubulointerstitial disease in the pathogenesis of salt-dependent hypertension. Kidney Int. 1997;52:1169–1179. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santisteban MM, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, et al. Involvement of bone marrow cells and neuroinflammation in hypertension. Circ Res. 2015;117:178–191. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ba D, Takeichi N, Kodama T, Kobayashi H. Restoration of t cell depression and suppression of blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (shr) by thymus grafts or thymus extracts. J Immunol. 1982;128:1211–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Breen LT, McHugh PE, Murphy BP. Huvec icam-1 and vcam-1 synthesis in response to potentially athero-prone and athero-protective mechanical and nicotine chemical stimuli. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:1880–1892. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9959-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen AR, McHale J, Smith J, et al. Endothelial expression of vcam-1 in experimental crescentic nephritis and effect of antibodies to very late antigen-4 or vcam-1 on glomerular injury. J Immunol. 1999;162:5519–5527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan SB, Allen AR, Bhangal G, et al. Blocking vla-4 prevents progression of experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2003;95:e100–110. doi: 10.1159/000074326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haass M, Kubler W. Nicotine and sympathetic neurotransmission. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1997;10:657–665. doi: 10.1007/BF00053022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tseng CJ, Appalsamy M, Robertson D, Mosqueda-Garcia R. Effects of nicotine on brain stem mechanisms of cardiovascular control. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:1511–1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chernyavsky AI, Arredondo J, Skok M, Grando SA. Auto/paracrine control of inflammatory cytokines by acetylcholine in macrophage-like u937 cells through nicotinic receptors. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serova L, Danailov E, Chamas F, Sabban EL. Nicotine infusion modulates immobilization stress-triggered induction of gene expression of rat catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:884–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawashima K, Fujii T. Expression of non-neuronal acetylcholine in lymphocytes and its contribution to the regulation of immune function. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2063–2085. doi: 10.2741/1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martelli D, Yao ST, McKinley MJ, McAllen RM. Reflex control of inflammation by sympathetic nerves, not the vagus. J Physiol. 2014;592:1677–1686. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.