Abstract

Theories of preview benefit in reading hinge on integration across saccades and the idea that preview benefit is greater the more similar the preview and target are. Schotter (2013) reported preview benefit from a synonymous preview, but it is unclear whether this effect occurs because of similarity between the preview and target (integration), or because of contextual fit of the preview—synonyms satisfy both accounts. Studies in Chinese have found evidence for preview benefit for words that are unrelated to the target, but are contextually plausible (Yang, Li, Wang, Slattery, & Rayner, 2014; Yang, Wang, Tong, & Rayner, 2012), which is incompatible with an integration account but supports a contextual fit account. Here, we used plausible and implausible unrelated previews in addition to plausible synonym, antonym, and identical previews to further investigate these accounts for readers of English. Early reading measures were shorter for all plausible preview conditions compared to the implausible preview condition. In later reading measures, a benefit for the plausible unrelated preview condition was not observed. In a second experiment, we asked questions that probed whether the reader encoded the preview or target. Readers were more likely to report the preview when they had skipped the word and not regressed to it, and when the preview was plausible. Thus, under certain circumstances, the preview word is processed to a high level of representation (i.e., semantic plausibility) regardless of its relationship to the target, but its influence on reading is relatively short-lived, being replaced by the target word, when fixated.

A key question in reading research regards the extent to which information about words obtained from parafoveal vision influences reading behavior. It is clear from over four decades of research, since the introduction of the gaze-contingent boundary paradigm (Rayner, 1975) and moving window paradigm (McConkie & Rayner, 1976), that parafoveal information is important for reading efficiency. In the moving window paradigm, the letters around the fixation location are revealed while letters beyond this visible window are masked and the size of the window is varied across experimental conditions. The general finding from these studies is that reading rate decreases as the size of the visible window becomes smaller (see Rayner, 2014 for a review). In the boundary paradigm, a particular target word in the sentence is selected to be manipulated: while the reader's eyes fixate parts of the sentence prior to that location the word is replaced by another preview stimulus (e.g., another word, a nonword, or a string of x's) and is only revealed when the reader makes an eye movement to fixate or skip over that location. The general finding from these studies is that fixation durations on the target word show a preview benefit—are shorter when the target was available as a parafoveal preview (i.e., in the identical preview condition) compared to when the reader had a parafoveal preview of a different stimulus, and there are moderate benefits for words that are not identical to the target but are similar to it in some way (e.g., visually, orthographically, phonologically; see Schotter, Angele, & Rayner, 2012 for a review).

Despite the large amounts of evidence that parafoveal information is important for reading efficiency, it is still not entirely clear how that information is used in the reading process. That is, initial explanations of parafoveal preview benefit invoked the idea of trans-saccadic integration—processing of the preview facilitates processing of the target in that, to the extent that they are similar, the access of properties of the preview allowed for a head-start on processing of the target. For example, Rayner (1975, p. 80) concluded that across saccades, “information from the two fixations is integrated… when visual or semantic discrepancies were introduced between two successive fixations, this integration failed.” Subsequently, Pollatsek, Lesch, Morris, and Rayner (1992, p. 159) concluded that word properties (i.e., phonology) are “used to preserve the `memory' of a word from one fixation to aid in its identification on the next fixation.” Thus, critical to an explanation by means of integration is the idea that greater similarity between preview and target (i.e., the more their orthographic, phonological, and/or semantic representations overlap) the greater the magnitude of preview benefit.

Initial investigations into preview benefit found data compatible with an integration account and lead to the general conclusion that semantic information was not used for integration. That is, there were several studies across many different languages demonstrating preview benefit from orthographically similar previews (Balota, Pollatsek, & Rayner, 1985; Briihl & Inhoff, 1995; Drieghe, Rayner, & Pollatsek, 2005; Inhoff, 1987, 1989a, 1989b, 1990; Inhoff & Tousman, 1990; Lima & Inhoff, 1985; Rayner, 1975; White, Johnson, Liversedge, & Rayner, 2008) and phonologically similar previews (Ashby & Rayner, 2004; Ashby, Treiman, Kessler, & Rayner, 2006; Chace, Rayner, & Well, 2005; Liu, Inhoff, Ye, & Wu, 2002; Miellet & Sparrow, 2004; Pollatsek et al., 1992; Rayner, Sereno, Lesch, & Pollatsek, 1995; Sparrow & Miellet, 2002; Tsai, Lee, Tzeng, Hung, & Yen, 2004). In contrast, initial investigations did not find any evidence for semantic preview benefit in English (Rayner, Balota, & Pollatsek, 1986, see Rayner, Schotter, & Drieghe, 2014 for a replication), but more recent studies in German and Chinese did find evidence for it (Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2014; Hohenstein, Laubrock, & Kliegl, 2010; Yan, Richter, Shu, & Kliegl, 2009; Yan, Zhou, Shu, & Kliegl, 2012; Yang, 2013; Yang, Wang, Tong, & Rayner, 2012). These differences in the findings were explained in terms of cross-language differences (see Laubrock & Hohenstein, 2012; Schotter, 2013, Schotter et al., 2012), until recent studies showed semantic preview benefit in English when the preview was a synonym of the target (e.g., start-begin: Schotter, 2013; see also Schotter, Lee, Reiderman, & Rayner, 2015). The suggested explanation for synonym preview benefit in English was attributed to the similarity of meaning between the two words (see discussions by Schotter, 2013; Rayner & Schotter, 2014) implying that meaning is what was being integrated between preview and target.

In subsequent work, Schotter et al. (2015) also found preview benefit for non-synonymous semantically related words (e.g., ready-begin) when they were embedded in semantically constraining contexts. Importantly, the constraining contexts used by Schotter et al., were not high cloze in the traditional sense in which one word form was very expected at the location of the preview/target. That is, in a modified cloze norming task (see Taylor, 1953 for the original task) in which subjects read the sentence fragment leading up to the target/preview location and had to fill in a word they thought could come next, the proportion of responses that corresponded to the target, synonym, and semantically related word were .21, .25, and .00, respectively. On traditional views of predictability, cloze values of around 25% are considered medium to low constraint (Rayner & Well, 1996). However, as Schotter et al. (2015) note, their sentences were constraining in the sense that a general meaning was highly expected, but that meaning could manifest itself as a variety of word forms, in particular both the target and synonym (i.e., the cloze probability for the shared meaning of the target, synonym preview, and other similar words was .75). They suggested that the sentence context generated expectations that whatever word would come next should be easily identifiable and, to the extent that that upcoming word had a meaning related to the event being described (e.g., the target, synonym, or a semantically related word), that preview facilitated processing and led to preview benefit. Indeed, the issue of how sentence contexts lead to linguistic prediction and how such prediction should be measured is an open area of research; for example, see preface (Hauk, 2016) to a recent special issue on prediction and language comprehension in Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, and various articles within it, as well as DeLong, Troyer, & Kutas, (2014; Schotter et al., 2015). As will be discussed below, the sentence constraint used in the current studies is slightly different than that used by Schotter et al. (2015).

From Schotter's (2013; Schotter et al., 2015) data it is unclear whether the preview benefit she observed was because of similarity between the preview and target or was due to compatibility between the preview and the sentence context. Importantly, because synonyms mean the same thing or are very similar in meaning they should fit approximately as well in the same sentence context (e.g., “The horse race will start/begin in a couple of minutes.”). Thus, an integration account and a contextual fit account can make divergent predictions. An integration account predicts that a word that is neither orthographically, phonologically, or semantically similar to the target but still fits into the sentence context should not provide preview benefit, whereas a contextual fit account predicts that such a condition should provide preview benefit. Most prior studies have not been able to address this issue because the focus has been on the relationship between the preview and target, rather than the preview and the sentence context. That is, many prior studies have not assessed the plausibility of the preview in the sentence context and many have used nonword previews, which by definition are implausible. Furthermore, the data from Schotter et al. (2015; Rayner et al., 1986, 2014; Schotter, 2013) cannot dissociate target-preview similarity from preview-context compatibility because the semantically related but non-synonymous conditions were not controlled for whether they were contextually plausible or implausible; for example, Schotter (2013) reports that, of the semantically associated previews, 17% were semantically anomalous and 13% were syntactically anomalous.

Although not designed to adjudicate between the integration and contextual fit accounts, two recent studies on reading in Chinese report patterns of data that are more compatible with the contextual fit account (Yang, Li, Wang, Slattery, & Rayner, 2014; Yang et al., 2012). Yang et al. (2012) found no benefit in reading time on the target for a semantically related preview relative to an unrelated preview when both those previews were implausible in the sentence context (Experiment 1), but they did find preview benefit for unrelated previews that were plausible in the sentence context compared to unrelated previews that were implausible (Experiment 2). Yang et al. (2014) conducted a study to determine whether the plausibility preview benefit was due to readers initially encoding the preview word rather than encoding the target word. Their study involved three preview conditions: (1) an identical word that was always plausible in the sentence context, (2) an unrelated word that was initially plausible in the preceding context but became implausible upon encountering the rest of the sentence and, (3) an unrelated word that was always implausible. They found that early reading time measures showed faster processing for the identical and initially plausible conditions compared to the implausible condition, replicating the effect of preview plausibility. However, they did not find evidence for a larger penalty to later reading (i.e., no more regressions or longer rereading times) in the initially plausible compared to the always implausible condition. They argue that these data challenge the idea that readers had encoded the initially plausible preview word (i.e., rather than the target). That is, had readers encoded and maintained the meaning of the initially plausible preview they would have eventually become confused when the sentence subsequently became implausible and would have spent more time rereading in that condition relative to the implausible condition, where readers would have been more likely to discard the implausible preview and encode the always plausible target word instead.

The results from the studies conducted by Yang and colleagues suggest that readers do obtain semantic information from a parafoveal preview because the plausibility of that word has an effect on initial reading measures on the target, but the effect is short-lived in that it does not appear in later reading measures where there is no difference between conditions with an unrelated preview that is initially plausible compared to always implausible. However, there are several crucial differences between Chinese and English that make it important to test whether a similar pattern would also be observed in English. Importantly, many of these differences have been argued to make it more likely to observe semantic preview benefit in Chinese than in English (e.g., Schotter, 2013; Yang et al., 2012). First, because many Chinese characters have radicals that encode semantics in the orthography, meaning may more readily be accessed directly from a parafoveal word. Second, because there are no spaces between characters in Chinese, upcoming words are closer to the fovea and may be processed more efficiently than upcoming words in alphabetic languages, due to higher acuity. Third, because of the lack of spaces, readers may need to allocate more attention to both the sentence context and parafoveal characters in order to properly segment characters into words so that they can properly program an eye movement to land in an optimal viewing location, which could also encourage deeper encoding of upcoming words (Yan, Kliegl, Richter, Nuthmann, & Shu, 2010; see also Li, Liu, & Rayner, 2015).

In the current studies we sought to conduct a study in English that was similar to those of Yang and colleagues, comparing unrelated preview words that were manipulated to be plausible in the sentence context or implausible. In addition, we included a comparison between synonym preview benefit and antonym preview benefit in Experiment 1 (as well as the corresponding identical, plausible unrelated and implausible unrelated conditions for the sentences in each stimulus set). In Experiment 2 we focus on the antonym set only in order to investigate whether readers had encoded the preview or target word by asking two-alternative forced choice comprehension questions after every sentence with response options that correspond to those two words.

The synonym condition is a replication of Schotter (2013; Schotter et al., 2015: e.g., used the same synonym pairs, award-prize, but with different sentences to accommodate the other preview conditions used here). Schotter (2013; Schotter et al., 2015) showed preview benefit for synonyms that was almost as large as the identical preview benefit. However, synonyms satisfy the assumptions of both accounts mentioned above in that the meanings of the two words are identical or very similar and, thus, both words are plausible in the sentence context. Therefore, if we were to assess which of those words (i.e., the target or its synonymous preview) the reader had encoded the reader might think those words were interchangeable. In contrast, antonyms (e.g., loose-tight) satisfy the constraints of the contextual fit account in that both words in the antonym pair fit well in similar contexts (for the most part in general, and always in the experiments reported below), but they do not satisfy all the assumptions of the integration account. That is, the antonym condition shares many properties to the synonym (i.e., sharing part of speech, and many semantic features), but should be less able to be integrated with the target because it represents the opposite meaning from the target whereas the synonym completely shares meaning with the target. It could be argued that antonyms share all features, except that one of them is flipped (e.g., the words large and small are both adjectives, regarding the size of an entity with the only difference being that large has a positive relative magnitude while small has a negative relative magnitude; see Hutchinson, 2003). A detailed investigation of these issues is beyond the scope of the current paper, but the antonym condition will be an important feature of Experiment 2, which assesses the reader's interpretation of the sentence (i.e., whether it includes the preview or the target) and that is easier to do by comparing antonyms than synonyms.

Finally, as noted above, we also included a condition in which the preview was completely unrelated to the target word, but was plausible in the sentence context (e.g., party-prize in the sentence “Dale's company gave him a huge party/prize for his hard work.”), replicating conditions used by Yang and colleagues, but for readers of English. If these words pattern differently from the synonym condition it would lend support for an integration account, but if they pattern similarly it would challenge such an account and support a contextual fit account.

Related to the use of the plausible unrelated preview condition, the present studies required a sentence constraint manipulation that was slightly different than that used by Schotter et al. (2015). That is, because the sentences needed to allow for the target word, synonyms of that word, as well as antonyms or a completely unrelated word, the sentence contexts necessarily have to be less constraining to a particular meaning than the 75% meaning constraint used by Schotter et al. (2015). Therefore, the cloze probability for the preview word forms in the current study (i.e., <5%) is lower than those reported by Schotter et al. (i.e., 15–35%), and the sentences used here did not converge onto one meaning to the same extent that theirs did (see normative data below).

In these studies, we used the boundary paradigm (Rayner, 1975) and focused on various preview conditions that allow us to investigate the degree to which fixation durations on a fixated word are influenced by the relationship between the parafoveal preview and foveal target information or whether the contextual fit of the preview word can facilitate reading in the absence of meaning similarity between preview and target. As is standard in boundary studies, we included an identical preview condition and an unrelated (i.e., implausible random word) preview condition, which represent two baselines with which to compare the other two preview conditions. The identical condition represents the case in which all the information is the same between preview and target and should afford the greatest opportunity for integration across saccades. The unrelated random word preview was always implausible in the sentence (i.e., syntactically or semantically anomalous) and represents the least easy to process condition, both in terms of a lack of similarity to the target and incompatibility with the sentence context. We also included a condition in which the preview was unrelated to the target word, but a plausible word in the sentence; the comparison between this condition and the implausible preview condition allows us to test the influence of the contextual fit of the preview word when it has no relationship to the target and extends the findings of Yang and colleagues to English. The final condition was either a synonym of the target (in 60% of the sentences) or an antonym of the target (in 40% of the sentences) in Experiment 1 to assess whether these conditions pattern similarly. In Experiment 2 we focus further on the antonym and plausible unrelated conditions in the set of antonym stimuli to ask specific questions about which word's meaning (i.e., the preview or the target) is ultimately represented in the reader's understanding of the sentence.

Experiment 1

Method

Subjects

Twenty-four undergraduates at the University of California, San Diego participated in the experiment for course credit. All were native English speakers, with normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were naïve to the purpose of the experiment.

Apparatus

An SR Research Ltd. Eyelink 1000 eye tracker (with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz) was used to record the readers' eye movements. The tracker was used in the tower setup with forehead and chin rests, decreasing noise due to head movements. Viewing was binocular, but only the movements of the right eye were recorded. Subjects were seated approximately 60 cm away from a 20” HP p1230 CRT monitor with a screen resolution of 1024 × 768 pixels and a refresh rate of 150 Hz. The sentences were presented in the center of the screen with black Courier New 14-point font on a white background and were always presented in one line of text with 2.41 characters subtending 1 degree of visual angle. Following calibration, eye position errors were less than 0.3° at each calibration point. The display change was completed, on average, within 4 ms (range = 0–7 ms) of the tracker detecting a saccade crossing the boundary.

Materials and Design

Stimuli were created out of 140 pairs of target words. Of these pairs, 56 were antonyms (e.g., loose-tight) and 84 were synonyms (e.g., prize-award). Two sentence frames were created for each pair such that each member of the pair was the target (and identical preview) in its own sentence frame and the other member was used as the preview in the synonym/antonym preview condition (depending on the stimulus set). In addition to these two preview conditions we also included two more conditions that were the same across the two sentence frames/targets, a plausible unrelated word or an implausible unrelated word to create a total of 4 conditions for each target word (see Table 1a and Appendix A). Thus, each subject read a total of 280 sentences with unique target words one time each in one of 4 possible preview conditions (identical, antonym/synonym, plausible unrelated, implausible unrelated). Preview condition was counterbalanced across subjects and items in a Latin square design such that each target word was encountered only once by a given subject, but across subjects each target word was encountered in every condition. Because each version of the antonym/synonym pair was used as a target this meant that on one fourth of the trials (i.e., in the antonym/synonym preview condition) the preview word was the same as a target word from another trial. However, because the order of the trials was randomized independently for each subject and preview conditions were counterbalanced across subjects and items, this design feature is unlikely to affect the data in any systematic way. The target/preview word was always preceded and followed by a minimum of 2 words.

Table 1a.

Example stimuli used in Experiment 1. Target words are presented in boldface, but were presented normally in the experiments.

| Example sentence with target word in boldface | Antonym/Synonym | Plausible | Implausible |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synonym stimulus set | |||

| Dale's company gave him a huge prize for his hard work. | award | party | weird |

| The kids were bored until the teacher offered a special award for doing well on a test. | prize | party | weird |

| Antonym stimulus set | |||

| Ron's pants are still loose even after tailoring. | tight | short | poles |

| The professor's coat is too tight for him. | loose | short | poles |

Normative Data

The stimuli were assessed via three norming procedures: two acceptability rating tasks (one for the sentence fragment up to and including the preview/target word and the other for the entire sentence) to assess whether the two versions of the sentence for each pair were equally sensible, and a cloze norming task to assess how predictable each of the preview/target word forms was, given the preceding sentence fragment. Results of the norming procedures and other characteristics of the stimuli are reported in Table 1b.

Table 1b.

Lexical characteristics of and normative data for target and preview words used in Experiment 1, presented separately by stimulus set. Standard errors are in parentheses.

| Set | Variable | Preview Condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identical | Antonym/Synonym | Plausible Unrelated | Implausible Unrelated | ||

| Antonym | |||||

| Length | 5.46 (.13) | 5.46 (.13) | 5.46 (.13) | 5.46 (.13) | |

| Log Frequency/mil (HAL) | 1.72 (.07) | 1.72 (.07) | 1.42 (.08) | 1.25 (.09) | |

| Acceptability Rating (fragment) | 5.9 (.07) | 5.7 (.10) | 5.2 (.13) | 2.2 (.07) | |

| Acceptability Rating (whole) | 5.8 (.11) | 5.5 (.07) | 5.4 (.05) | 2.0 (.10) | |

| Cloze Probability | .04 (.01) | .02 (.01) | .03 (.01) | .00 (.00) | |

| Synonym | |||||

| Length | 5.49 (.09) | 5.49 (.09) | 5.49 (.09) | 5.49 (.09) | |

| Log Frequency/mil (HAL) | 1.35 (.06) | 1.35 (.06) | 1.54 (.06) | 1.56 (.06) | |

| Acceptability Rating (fragment) | 5.9 (.05) | 5.1 (.09) | 5.3 (.08) | 2.7 (.09) | |

| Acceptability Rating (whole) | 5.2 (.08) | 5.7 (.05) | 5.5 (.08) | 3.3 (.07) | |

| Cloze Probability | .02 (.01) | .02 (.01) | .03 (.01) | .00 (.00) | |

Forty-eight workers on Amazon's Mechanical Turk participated in one of two acceptability judgment tasks—one in which they rated the acceptability of the entire sentence, and one in which they rated the acceptability of the sentence fragment up to and including the preview/target word. In this task, subjects rated sentences or sentence fragments on a 7-point Likert scale to indicate how well they were written. The four versions of the sentence or fragment (i.e., including one of the four different preview words) were counterbalanced across four lists per task (i.e., sentence or fragment) so that each version of each sentence or fragment was rated by six independent raters and each rater saw a quarter of the stimuli in each condition (as well as 36 poorly written filler sentences or fragments). The data revealed that the words that were intended to be sensible in the sentence context were rated highly (5.1–5.9) whereas the implausible words were rated low (2.0–3.3).

A separate group of 14 subjects participated in a cloze norming task (adapted from Taylor, 1953) in which they were provided with the sentence fragment leading up to the target/preview word and were required to fill in a word they thought could come next. Seven subjects completed the task for one of the sentence frames of the pair and the other seven completed the task for the other sentence frame of the pair to avoid carry-over in the responses between pairs that contained sentence frames that were somewhat similar in meaning. These data revealed that the sentences were not constraining to the word forms of any of the previews or targets. The average cloze probabilities were .03, .02, .03, and .00 for the identical, synonym/antonym, plausible unrelated, and implausible unrelated preview, respectively. Following Schotter et al. (2015), we coded the responses to determine the predictability of the meaning shared by the target and synonym (and any other synonymous words) for the synonym stimulus set only because it was not possible to define the measure for antonyms or unrelated words. This measure revealed that the cloze probability for the meaning shared between the target and synonym was 11%, much lower than that for Schotter et al.'s sentences (75%).

Procedure

Subjects were instructed to read the sentences for comprehension and to respond to occasional comprehension questions, pressing the left or right trigger on the response controller to answer yes or no, respectively. At the start of the experiment (and during the experiment if calibration error was greater than .3 degrees of visual angle), the eye-tracker was calibrated with a 3-point calibration scheme. At the beginning of the experiment, subjects received five practice trials, each with a comprehension question, to allow them to become comfortable with the experimental procedure.

Each trial began with a fixation point in the center of the screen, which the subject was required to fixate until the experimenter started the trial. Then a fixation box appeared on the left side of the screen, located at the start of the sentence. Once a fixation was detected in this box, it disappeared and the sentence appeared. The sentence was presented on the screen until the subject pressed a button signaling they had completed reading the sentence. Following the boundary paradigm (Rayner, 1975), the target replaced the preview once the subject's gaze crossed an invisible boundary located before the space before the target and took between 0 and 7 ms to complete. Subjects were instructed to look at a target sticker on the right side of the monitor beside the screen when they finished reading to prevent them from looking back to a word (in particular, the target, which was often located in the center of the sentence, near the location of the fixation point that started the next trial) as they pressed the button. Comprehension questions followed 72 (26%) of the sentences, requiring a “yes” or “no” response. Comprehension accuracy was very high (on average 91%). At the end of the experiment subjects were asked whether they noticed the screen flickering or words changing (i.e., display changes). The rate of display changes noticed was very low, between 0 and 15 trials (mean = 3.83), because subjects who reported more than this (an indication of equipment or experimenter error) were replaced without their data being analyzed, as is common in boundary paradigm experiments. The experimental session lasted approximately 40 minutes.

Results

Trials in which there was a blink or track loss on the target word during first pass reading were excluded (7.5% of the data), as were trials in which the display change was triggered by a saccade that landed to the left of the boundary or trials in which the display change was completed late (16% of the data). These data exclusions left 5335 trials (79% of the original data) available for analysis. Fixations longer than 800 ms were eliminated, as were fixations shorter than 80 ms, unless they were within one character space of a previous or subsequent fixation, in which case they were combined with that fixation. Gaze durations longer than 2,000 ms and total times longer than 4,000 ms were excluded (< 1% of fixations), as well as any fixation duration measures that were more than 2.5 standard deviations from the mean for that measure for that subject (1.4–2.2% of fixations across measures) because they are unlikely to represent normal reading (i.e., the subject may have been zoning out at the moment and had an unusually long fixation).

We report standard reading time measures (Rayner, 1998) used to investigate the time-course of word processing in reading, including first fixation duration (the duration of the first fixation on the word, regardless of how many fixations are made), single fixation duration (the duration of a fixation on a word when it is the only fixation on that word in first pass reading), gaze duration (the sum of all fixations on a word prior to leaving it, in any direction), go-past time (the sum of all fixations on a target word and all fixations on words to the left of it, starting from the first fixation on that word before going past the target word to the right), and total time (the sum of all fixations on a word, including time spent re-reading the word after a regression back to it). In addition, we analyzed three measures of fixation probability, including fixation probability (the probability that the target was fixated at least once during first-pass reading), probability of regressing out of the target (i.e., to reread words prior in the sentence), and probability of regressing into the target (i.e., from subsequent words in the sentence).

Data were analyzed using inferential statistics based on general(ized) linear mixed-effects models (GLMMs) with stimulus set entered with a centered contrast, preview condition entered with planned contrasts (see below), as well as the interaction between them entered as the fixed effects. In addition, we entered subjects and items as crossed random effects (see Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008), using the maximal random effects structure: intercepts and slopes for both factors and the interaction for subjects, and intercepts and the preview contrasts for items (Barr, Levy, Scheepers & Tily, 2013)1. To assess whether there was a different pattern of effects between the antonym and synonym stimuli we entered stimulus set, centered, as a main effect and also its interaction with the preview contrasts. For the preview contrasts, the unrelated word was used as the baseline condition and three planned preview contrasts tested for preview benefit in the three other preview conditions: one tested the difference between the identical condition and the implausible unrelated condition (i.e., an identical preview benefit), another tested for a difference between the synonym/antonym condition and the implausible unrelated condition (i.e., a synonym/antonym preview benefit), and the third tested for a difference between the plausible unrelated condition and the implausible unrelated condition (i.e., a plausibility preview benefit).

In order to fit the LMMs, we used the lmer function from the lme4 package (version 1.1-8; Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) within the R Environment for Statistical Computing (R Development Core Team, 2015). For fixation duration measures, we report linear mixed-effects regressions on the raw data: regression coefficients (b), which estimate the effect size (in milliseconds) of the reported comparison, standard error, and the (absolute) t-value of the effect coefficient. Log-transforming the dependent variable had almost no effect on the patterns of significance, so for transparency we report the results from the untransformed models and note when the results from the models on transformed data differed. For binary dependent variables (fixation probability data), logistic mixed-effects regression models were used, and regression coefficients (b), which represent effect size in log-odds space, and the (absolute) z value and p value of the effect coefficient are reported. Absolute values of the t and z statistics greater than or equal to 1.96 indicate an effect that is significant at approximately the .05 alpha level. Reading measures on the target word are shown in Table 2, results of the LMMs on fixation duration measures are reported in Table 3 and results of the fixation probability measures are reported in Table 4.

Table 2.

Means and standard errors, aggregated by subject, for reading time measures in Experiment 1.

| Measure | Set | Preview condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identical | Antonym/Synonym | Plausible Unrelated | Implausible Unrelated | ||

| First Fixation Duration | Antonym | 222 (5.1) | 221 (5.8) | 224 (4.8) | 231 (6.1) |

| Synonym | 223 (4.9) | 227 (5.3) | 230 (5.1) | 238 (5.2) | |

| Single Fixation Duration | Antonym | 224 (5.3) | 222 (6.1) | 226 (5.3) | 237 (6.9) |

| Synonym | 228 (5.2) | 232 (6.3) | 233 (5.8) | 244 (6.1) | |

| Gaze Duration | Antonym | 238 (6.5) | 238 (6.7) | 246 (6.0) | 256 (8.4) |

| Synonym | 243 (7.6) | 242 (7.5) | 246 (7.2) | 260 (8.4) | |

| Go-Past Time | Antonym | 259 (8.6) | 264 (11) | 280 (10) | 306 (12) |

| Synonym | 284 (13) | 269 (10) | 284 (11) | 297 (12) | |

| Total Time | Antonym | 288 (10) | 306 (13) | 323 (14) | 325 (13) |

| Synonym | 293 (12) | 298 (14) | 315 (14) | 316 (12) | |

| Fixation Probability | Antonym | 0.82 (.03) | 0.82 (.03) | 0.82 (.03) | 0.85 (.03) |

| Synonym | 0.81 (.03) | 0.81 (.03) | 0.81 (.03) | 0.84 (.03) | |

| Regressions out | Antonym | 0.08 (.01) | 0.09 (.02) | 0.10 (.02) | 0.14 (.02) |

| Synonym | 0.11 (.02) | 0.09 (.01) | 0.10 (.02) | 0.12 (.02) | |

| Regressions in | Antonym | 0.17 (.03) | 0.21 (.03) | 0.22 (.03) | 0.22 (.02) |

| Synonym | 0.14 (.02) | 0.18 (.03) | 0.19 (.02) | 0.20 (.02) | |

Table 3.

Results of the linear mixed effects models for reading time measures on the target across preview conditions (i.e., identical, antonym/synonym, plausible unrelated, and implausible unrelated) and stimulus sets (i.e., the antonym set and the synonym set), including the interaction term. The left hand column represents the average effects across stimulus sets (because stimulus set was entered as a centered predictor) and the right hand column represents the tests for interactions between the preview contrasts and stimulus set. In the left hand columns, the intercept represents the implausible unrelated condition and the subsequent rows test for preview benefit effects—the difference between the named condition and the intercept. Significant effects are indicated by boldface.

| Measure | Contrast | Overall Preview Benefit | Interaction with Stimulus Set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | |t| | b | SE | |t| | ||

| First Fixation Duration | |||||||

| Intercept | 234.84 | 5.23 | 44.89 | 4.77 | 5.38 | 0.89 | |

| Identical | −12.01 | 4.21 | 2.85 | −3.60 | 5.95 | 0.60 | |

| Antonym/Synonym | −12.02 | 3.64 | 3.30 | 2.49 | 6.46 | 0.39 | |

| Plausible | −7.35 | 3.56 | 2.06 | 0.37 | 7.01 | 0.05 | |

| Single Fixation Duration | |||||||

| Intercept | 240.01 | 5.94 | 40.40 | 4.76 | 5.48 | 0.87 | |

| Identical | −13.44 | 4.63 | 2.90 | −1.75 | 6.20 | 0.28 | |

| Antonym/Synonym | −13.67 | 4.23 | 3.23 | 4.94 | 6.45 | 0.77 | |

| Plausible | −9.98 | 4.03 | 2.48 | 0.24 | 7.47 | 0.03 | |

| Gaze Duration | |||||||

| Intercept | 258.10 | 8.06 | 32.01 | 3.79 | 5.97 | 0.63 | |

| Identical | −18.27 | 6.21 | 2.94 | 1.13 | 6.73 | 0.17 | |

| Antonym/Synonym | −19.22 | 5.21 | 3.69 | 1.14 | 7.36 | 0.16 | |

| Plausible | −11.53 | 5.24 | 2.20 | −5.21 | 7.47 | 0.70 | |

| Go-Past Time | |||||||

| Intercept | 301.16 | 11.71 | 25.73 | −8.37 | 9.70 | 0.86 | |

| Identical | −30.18 | 8.09 | 3.73 | 33.81 | 11.07 | 3.05 | |

| Antonym/Synonym | −33.67 | 7.72 | 4.36 | 13.16 | 12.68 | 1.04 | |

| Plausible | −19.08 | 7.51 | 2.54 | 11.48 | 12.77 | 0.90 | |

| Total Time | |||||||

| Intercept | 320.56 | 12.08 | 26.54 | −7.50 | 10.34 | 0.73 | |

| Identical | −32.06 | 7.86 | 4.08 | 14.98 | 12.19 | 1.23 | |

| Antonym/Synonym | −18.29 | 7.57 | 2.42 | 1.44 | 12.60 | 0.11 | |

| Plausible | −1.12 | 6.43 | 0.17 | 1.58 | 15.40 | 0.10 | |

Table 4.

Results of the linear mixed effects models for reading probability measures on the target across conditions. The left hand column represents the average effects across stimulus sets (because stimulus set was entered as a centered predictor) and the right hand column represents the tests for interactions between the preview contrasts and stimulus set. In the left hand columns, the intercept represents the implausible unrelated condition and the subsequent rows test for preview benefit effects—the difference between the named condition and the intercept. Significant effects are indicated by boldface.

| Measure | Contrast | Overall Preview Benefit | Interaction w/ Set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | |z| | p | b | |z| | p | ||

| Fixation Probability | |||||||

| Intercept | 2.27 | 7.77 | < .001 | 0.18 | 0.69 | .49 | |

| Identical | −0.39 | 2.13 | < .05 | −0.14 | 0.44 | .66 | |

| Antonym/Synonym | −0.33 | 1.88 | .06 | −0.44 | 1.26 | .21 | |

| Plausible | −0.21 | 1.15 | .25 | −0.51 | 1.52 | .13 | |

| Regressions Out | |||||||

| Intercept | −2.16 | 12.12 | < .001 | −0.22 | 1.14 | .25 | |

| Identical | −0.35 | 2.26 | < .05 | 0.63 | 2.39 | < .05 | |

| Antonym/Synonym | −0.42 | 2.23 | < .05 | 0.21 | 0.78 | .44 | |

| Plausible | −0.32 | 1.66 | .10 | 0.23 | 0.89 | .38 | |

| Regressions In | |||||||

| Intercept | −1.49 | 11.22 | < .001 | −0.13 | 0.75 | .45 | |

| Identical | −0.66 | 3.55 | < .001 | −0.20 | 0.71 | .48 | |

| Antonym/Synonym | −0.14 | 0.99 | .32 | −0.14 | 0.55 | .58 | |

| Plausible | −0.003 | 0.02 | .99 | −0.04 | 0.19 | .85 | |

Fixation duration measures

None of the interactions between stimulus set and preview benefit contrast were significant2, suggesting that the effects were similar for synonyms and antonyms (i.e., for the synonym/antonym contrast) and across different types of stimuli (for the identical and plausible unrelated preview benefit). Therefore, while the analyses and tables reported below maintain the interaction term in the models, we discuss the preview benefit effects together for brevity and simplicity. For all reading time measures, there was a significant identical preview benefit (all ts > 2.84) and a significant antonym/synonym preview benefit (all ts > 2.41), replicating the effect reported by Schotter (2013; Schotter et al., 2015) for synonyms and extending the effect to antonyms. The preview benefit provided by the plausible unrelated word was also significant in all early reading time measures (all ts > 2.05), replicating Yang and colleagues' findings in English and suggesting that it is unlikely that integration between the preview and target can completely explain the other preview benefit effects observed here. That is, because there is no relationship between the preview and target, it is unclear what information would be integrated in order to facilitate processing once the target word was fixated.

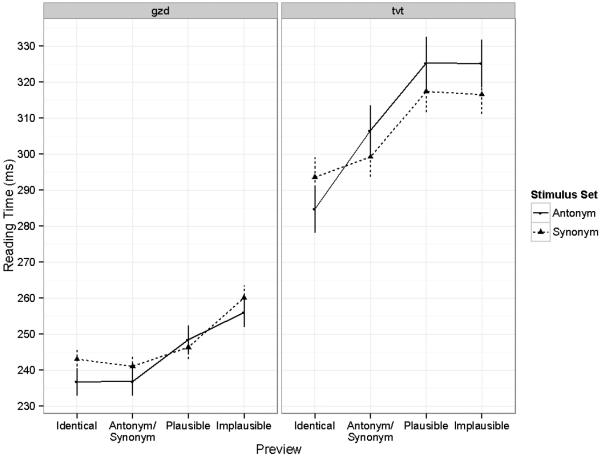

The plausibility preview benefit was not significant in total time (t = 0.17), which includes any time spent re-reading the target after moving past it. Furthermore, the antonym/synonym preview condition produced reading times closer to the identical preview condition in early reading time measures (e.g., gaze duration) than in total time (Figure 1), suggesting that any benefits from having a plausible but non-identical preview were relatively short-lived and diminished once the reader had moved past the word (leading to a higher likelihood of making a regression back to the target, see below).

Figure 1.

Reading time on the target word in Experiment 1 as a function of preview condition and stimulus set (antonyms or synonyms), across 2 reading time measures (gzd = gaze duration, tvt = total time).

Fixation probability measures

None of the interactions with stimulus set were significant, indicating the same pattern of effects for both sets3 so we discuss the patterns of preview effects together. Moreover, the lack of interaction between the intercept and stimulus set indicates that there was no effect of stimulus set in the implausible unrelated condition, and the additional lack of interactions with the preview contrasts suggests that the overall main effect of stimulus set was not significant overall.

For fixation probability, only the contrast for the identical preview was significant (p < .05)4, indicating that the identical preview was fixated less often than the implausible unrelated word. The contrast for the antonym/synonym preview was marginally significant (p = .06), also indicating that these previews were fixated slightly less often than implausible unrelated preview. The contrast for the plausible unrelated previews was not significant (p > .24), indicating that those previews were fixated as frequently as the implausible unrelated preview.

For regressions out of the target word, both the contrasts for the identical preview and the antonym/synonym were significant (both ps < .05), indicating that those preview conditions produced fewer regressions out of the target than the implausible unrelated preview condition. The contrast for the plausible unrelated preview was not significant (p = .10), indicating an approximately equivalent rate of regressions out as in the implausible unrelated preview condition.

For regressions into the target word, only the contrast for the identical preview condition was significant (p < .001.), indicating fewer regressions in the identical preview condition than in the implausible unrelated preview condition, which did not differ from the other preview conditions (both ps > .31).

Discussion

There are several important aspects of the data from Experiment 1. The lack of interactions between the antonym/synonym contrast and stimulus set suggests that the preview benefit for synonyms observed by Schotter (2013; Schotter et al., 2015) cannot exclusively be explained by similarity and trans-saccadic integration of meaning between the preview and target. Instead, it is possible that, since both the synonym and antonym preview were plausible in the sentence context, the contextual fit of the preview itself (i.e., post-lexical integration of the word in the sentence context) might explain the observed preview benefit, as suggested by Yang and colleagues. Moreover, this interpretation is supported by the data from the plausible unrelated preview condition, which provided preview benefit in all reading time measures except for total time, which includes regressions back into the target. Because the preview in this condition did not share any meaningful relationship with the target it is unlikely that a similarity-based or integration-based account can explain these data. Furthermore, this condition replicates the plausibility effects observed by Yang and colleagues and extends the effect from Chinese to English. The preview benefit for the plausible unrelated condition likely disappeared in total time because, after the reader had fixated and processed the target word, discrepancies between its orthographic and/or semantic form and that of the preview lead to increased re-reading time. The total time data suggest that there is more of a benefit for antonym and synonym previews, which are semantically similar to the target word and thus may mostly carry a cost of difference in orthography, than for plausible unrelated previews, which may impose costs for both orthographic and semantic discrepancies between representations (see General Discussion).

In light of these data, instead of an account that invokes integration, we favor an account whereby preview benefit for first-pass measures can be explained in terms of ease of processing the preview per se via its compatibility with the sentence context (in addition to lexical features like word frequency and predictability; see Schotter et al., 2015; Schotter, Reichle, & Rayner, 2014). We will elaborate on this account in the General Discussion, but note here that the three conditions in Experiment 1 that lead to the fastest first-pass reading times were those where the preview was plausible in the sentence context. As noted by Yang and colleagues (2012, 2014), this finding suggests that readers were able to access a linguistically high level of information from the preview word—not only its meaning but also the extent to which that meaning was appropriate in the sentence context. This then raises the question of whether the readers had obtained so much information from the preview that they had actually encoded that word rather than the target word when the preview was a plausible word in the sentence. We explore this possibility in Experiment 2.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 was designed to assess which of the two words—the preview or the target—the subject had interpreted by the time he or she had finished reading the sentence. We took an approach first reported by Blanchard, McConkie, Zola, and Wolverton (1984), in which there was a comprehension question after each sentence that, in display change conditions, could be answered with either the preview or the target (see details in the method section, below). For the identical (i.e., non display change) condition there was a comprehension question that asked about parts of the sentence other than the target in order to encourage the subjects to read for comprehension and not merely recognize and remember individual words. We analyzed the responses to the questions in relation to the eye movement behavior to assess (1) whether subjects ever reported the preview word, and (2) what experimental conditions and eye movement behaviors made reporting the preview word more likely.

Method

Subjects

Twenty-four UCSD students participated in the experiment for course credit. None had participated in Experiment 1, but they were selected using the same inclusion criteria.

Apparatus

The apparatus was the same as in Experiment 1.

Materials and design

Because it would be confusing for subjects to choose between two synonyms in the comprehension questions, this experiment used only the antonym sentences from Experiment 1. Additionally, two sentences from the antonym stimulus set were excluded because it was not possible to create a comprehension question that satisfied our constraints, yielding 110 experimental sentences. Every sentence was followed by a question, which differed depending on the experimental condition. In the identical preview condition, the question was a general comprehension question that did not refer to the target word. For both the antonym and plausible unrelated preview conditions, the question was designed such that either the preview or target could be plausible answers. For the unrelated preview condition the question directly asked which word the subject read (see Table 5 and Appendix B). The response options were presented in all capital letters whereas the preview and target words in the sentence were presented normally in lower case letters so that subjects could not rely on visual memory of the words in the sentence to make their response.

Table 5.

Example questions across condition in Experiment 2 for the example sentence “Ron's pants are still loose/tight/short/poles even after tailoring.”

| Preview Condition | Question | Option 1 | Option 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identical | Did Ron get his pants tailored? | Yes | No |

| Antonym | How are Ron's pants now? | LOOSE | TIGHT |

| Plausible | How are Ron's pants now? | LOOSE | SHORT |

| Implausible | Which of these words did you read? | LOOSE | POLES |

Procedure

The procedure was the same as in Experiment 1 except questions followed 100% of the sentences and differed depending on experimental condition (see above) and the experimental session lasted approximately 30 minutes. The rate of display changes noticed was very low, between 0 and 15 trials (mean = 2.42). Comprehension accuracy in the identical preview condition (i.e., the general comprehension questions) was high (on average 95%). Responses to the questions that probed whether the subjects had maintained the preview or target representation are reported below.

Results

Data processing procedures were the same as for Experiment 1, leaving 2156 trials for analysis (82% of the original data: 7.5% of trials were excluded for blinks and track loss, 13.5% of trials were excluded for late or inappropriate display changes; < 1% of long or short fixations were excluded, and 1.4–2.4% of fixations were excluded based on standard deviation by subject). Data analysis procedures were mostly the same except only the contrasts to test for preview benefit were used as fixed and random effects because there was only one stimulus set: the intercept of the model was the implausible unrelated word and the preview contrasts tested for the difference of each of the other preview conditions compared to the baseline, independently5. Reading measures on the target word are shown in Table 6, results of the LMMs on fixation duration measures are reported in Table 7 and results of the fixation probability measures are reported in Table 8.

Table 6.

Means and standard errors, aggregated by subject, for reading time measures in Experiment 2.

| Measure | Preview condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identical | Antonym | Plausible | Implausible | |

| First Fixation Duration | 217 (5.7) | 218 (6.0) | 227 (6.3) | 236 (6.4) |

| Single Fixation Duration | 222 (5.9) | 223 (6.6) | 231 (7.5) | 245 (6.5) |

| Gaze Duration | 235 (7.6) | 241 (7.7) | 245 (8.2) | 266 (8.8) |

| Go-Past Time | 267 (11) | 275 (13) | 273 (10) | 313 (13) |

| Total Time | 293 (12) | 333 (17) | 341 (16) | 350 (16) |

| Fixation Probability | .85 (.03) | .87 (.03) | .85 (.03) | .86 (.03) |

| Regressions out | .10 (.02) | .09 (.02) | .09 (.01) | .15 (.02) |

| Regressions in | .16 (.02) | .23 (.02) | .25 (.03) | .23 (.03) |

Table 7.

Results of the linear mixed effects models for reading time measures on the target across conditions in Experiment 2. Significant effects are indicated by boldface.

| Measure | Contrast | b | SE | |t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Fixation Duration | ||||

| Intercept | 235.58 | 6.65 | 35.43 | |

| Identical | −18.31 | 4.39 | 4.17 | |

| Antonym | −17.17 | 5.11 | 3.36 | |

| Plausible | −8.50 | 4.50 | 1.89 | |

| Single Fixation Duration | ||||

| Intercept | 244.87 | 6.77 | 36.19 | |

| Identical | −24.32 | 4.99 | 4.87 | |

| Antonym | −20.49 | 5.57 | 3.68 | |

| Plausible | −13.17 | 5.68 | 2.32 | |

| Gaze Duration | ||||

| Intercept | 265.54 | 9.10 | 29.17 | |

| Identical | −31.66 | 5.72 | 5.54 | |

| Antonym | −23.47 | 6.31 | 3.72 | |

| Plausible | −20.43 | 5.88 | 3.47 | |

| Go-Past Time | ||||

| Intercept | 313.83 | 14.00 | 22.41 | |

| Identical | −49.48 | 11.06 | 4.47 | |

| Antonym | −37.39 | 9.55 | 3.92 | |

| Plausible | −39.89 | 9.65 | 4.13 | |

| Total Time | ||||

| Intercept | 349.52 | 16.12 | 21.68 | |

| Identical | −60.07 | 10.95 | 5.49 | |

| Antonym | −14.46 | 10.08 | 1.44 | |

| Plausible | −8.12 | 11.03 | 0.74 |

Table 8.

Results of the linear mixed effects models for reading probability measures on the target across conditions in Experiment 3. Significant effects are indicated by boldface.

| Measure | Contrast | b | |z| | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation Probability | ||||

| Intercept | 2.51 | 7.64 | < .001 | |

| Identical | −0.31 | 1.04 | .30 | |

| Antonym | −0.05 | 0.16 | .87 | |

| Plausible | −0.47 | 1.71 | .09 | |

| Regressions Out | ||||

| Intercept | −2.02 | 9.10 | < .001 | |

| Identical | −0.64 | 1.84 | .07 | |

| Antonym | −0.75 | 2.39 | < .05 | |

| Plausible | −0.31 | 1.20 | .23 | |

| Regressions In | ||||

| Intercept | −1.47 | 7.58 | < .001 | |

| Identical | −0.33 | 1.42 | .16 | |

| Antonym | 0.08 | 0.34 | .73 | |

| Plausible | 0.33 | 1.64 | .10 |

Fixation duration measures

The fixation data from Experiment 2 mostly replicate the patterns of data from Experiment 16. For all duration measures, the identical preview benefit was significant (all ts > 4.16). For all early duration measures the antonym preview benefit was significant (all ts > 3.35), but the effect was not significant in total time (t = 1.44) whereas it was significant in Experiment 1. It is likely that the high occurrence of word-specific comprehension questions caused the readers to be more cautious about their understanding of the sentences, which eradicated the effect in the antonym condition. That is, because antonyms do not have identical meanings, if readers had encoded both the preview from parafoveal vision and the target, once it was directly fixated, these two representations might compete in the comprehension system and cause the reader to make a regression to double check the meaning of the sentence. This is more likely to happen when they encounter questions after every sentence that require a precise understanding of the meaning of the sentence (as in Experiment 2) than when the questions appear less often and only probe a general understanding of the text (as in Experiment 1). The plausible unrelated preview benefit was significant in single fixation duration, gaze duration, and go-past time (all ts > 2.31), marginally significant in first fixation duration (t = 1.89) and was not significant in total time (t < 1). The non-significant preview benefit in total time for the plausible unrelated condition was not observed in Experiment 1 either. We suspect that this is also because of the difference in meaning between the sentences with the preview and target, as noted above. However, because the meanings are so different, this was observed even in the first experiment, with lower comprehension demands.

Fixation probability measures

There were no significant differences across preview condition for the probability of making a first-pass fixation on the target (all ps > .08)7. For regressions out of the target, numerically all plausible conditions had lower regression rates than the implausible condition, but only the difference for the antonym condition was significant (p < .05). For the probability of making a regression into the target, none of the contrasts were significant (all ps > .09), even though numerically, there was a lower rate of regressions in the identical preview condition than in the other preview conditions.

Comprehension analyses

In order to investigate whether readers had identified and maintained the preview information, we analyzed the readers' responses to the questions. Critically, the questions in the display change conditions allowed us to probe which of the words the reader had interpreted by the end of the sentence. For the most part, readers reported the target rather than the preview word, suggesting that the information from a directly fixated word was maintained more strongly than (or replaced) the information obtained only from a parafoveally viewed word.

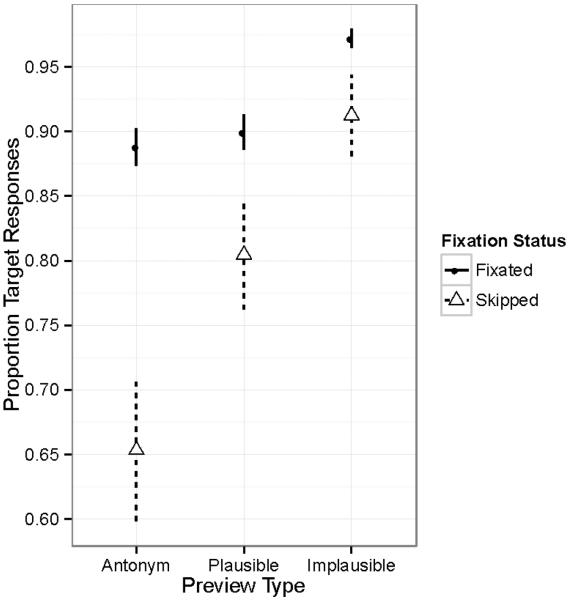

The only fixation related measure that showed a relationship with the reader's response was the measure of skipping. To assess this relationship we conducted a mixed effects logistic regression analysis with the reader's response on each trial (i.e., target coded as 1 vs. preview coded as 0) as the dependent measure and two variables (including their interaction) as predictors. The first predictor was the probability of skipping the preview/target word, entered as a centered predictor, and the second variable was preview condition entered with successive differences contrasts that tested for (1) a difference between the implausible and plausible condition and (2) a difference between the plausible and antonym condition. We included random slopes only for preview condition since there was very little variability in skipping the preview/target word. The identical preview condition was excluded from the analyses because the comprehension question did not assess whether the subjects remembered the preview versus the target.

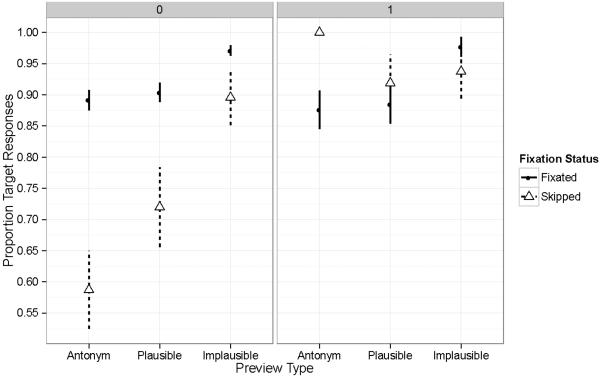

The analysis revealed a significant effect of skipping on the readers' responses; readers were more likely to respond that they had read the target word when they had fixated it than when they had skipped it (p < .001). There were also differences across experimental conditions; in the antonym preview condition, subjects reported the preview 14% of the time, more often than in the plausible unrelated preview condition (11% of the time; p < .01), which was more likely than in the implausible unrelated preview condition (only 3% of the time; p < .01). Furthermore, there was one significant interaction between skipping and experimental condition whereby the effect of skipping the word (i.e., increased likelihood of reporting the preview if the reader had skipped it) was more pronounced in the antonym preview condition (an average effect size of 22 percentage points) than in the plausible unrelated preview condition (an average effect size of 9 percentage points; interaction p < .05). The effect of skipping in the plausible unrelated condition did not differ from the effect of skipping on the probability of reporting the target in the implausible unrelated preview condition (an average effect of 4 percentage points; interaction p > .13; Figure 2). In addition, this pattern held (and was slightly more pronounced) for trials in which the reader did not make a regression (Figure 3, left panel) but did not hold when the reader made a regression and therefore directly fixated the target word (Figure 3, right panel). Therefore, the effect seems to be completely dissolved if the target word is fixated at all during reading of the sentence.

Figure 2.

Proportion of trials in which the reader selected the response that indicates that he or she had maintained the representation of the target as a function of whether the target was fixated (filled circles) or skipped (open triangles) and preview condition in Experiment 2.

Figure 3.

Proportion of trials in which the reader selected the response that indicates that he or she had maintained the representation of the target as a function of whether the target was fixated (filled circles) or skipped (open triangles) and preview condition in Experiment 2, split by trials in which the reader did not make a regression back to the target (left panel) or did make a regression (right panel).

Discussion

The data from Experiment 2 replicate the main pattern of eye movement measures from Experiment 1. In addition, analysis of the comprehension questions that were designed to assess which of the words (i.e., the preview or target) the reader had encoded by the end of the sentence shows an interesting, but not necessarily surprising finding. Mainly, readers almost always maintained the representation of the target word by the end of the sentence, leading to rates of reporting the target rather than the preview of around 90%. Importantly, however, the probability of reporting the preview increased when the reader had skipped the target and never regressed to fixate it, suggesting that words that are directly fixated are more likely to be encoded than words that are only viewed in parafoveal vision. However, in the absence of direct fixation on the target word, a parafoveal preview was sufficient for the preview to be encoded and maintained in the reader's interpretation of the sentence, except when the preview word was implausible.

These data might help to explain why Yang et al. (2014) did not find evidence in their regression data that Chinese readers encoded the plausible preview word. In their study readers only skipped the preview/target word 4% of the time and they did not report an analysis comparing regression behavior between trials in which the target word was fixated compared to when it was skipped. Therefore, it might be that readers in their study did not maintain the meaning of the preview word because they had fixated the target word and its representation overrode the representation of the target word.

General Discussion

The results from these studies add to a growing body of literature (Rayner & Schotter, 2014; Schotter et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2012, 2014) that suggest that preview benefit may not necessarily operate through integration of preview and target information, as was initially assumed. Instead, these data suggest that, to the extent that information can be obtained from the preview to cause the upcoming word to be skipped, preview information may be sufficient to support efficient reading. In such cases, readers are likely to encode and maintain the representation of the preview and may be completely unaware that the stimulus had actually changed to something else as they were reading, leading to a higher likelihood of reporting the preview on skipping trials in Experiment 2. Indeed, this proposition is not new and researchers have posited that skipping of words does indicate that readers had obtained a significant amount of meaningful information from (if not completely identified) the target (see Rayner, 2009).

However, the pattern of data for early eye movement measures in both Experiments 1 and 2, in which we observed shorter reading time on directly fixated target words following any plausible parafoveal preview regardless of its relationship to the target (i.e., synonym, antonym, or completely unrelated), suggests that the influence of the preview's meaning is not completely confined to the measure of skipping. Importantly, the fact that all of the plausible conditions, regardless of the preview's relationship to the target, yielded a preview benefit in early fixation duration measures challenges an integration account in favor of a contextual fit account. However, the effect of preview plausibility is relatively short-lived and the benefit of an unrelated yet plausible preview is not seen in later reading time measures. What might be driving the effects of the preview on early fixations on the target if not integration across saccades, and why do those effects differ from the pattern of data in later measures?

It may be the case that the contextual fit account is most appropriate to explain the first-pass reading data since the preview information is available earlier (i.e., from parafoveal vision) than the target information. Target information is only available once the word is fixated, after the delay for transmission of information from the retina to the brain (i.e., the 50–60 ms eye-brain lag; see Reichle & Reingold, 2013 for a review,) and then after some amount of time required for linguistic processing of the content of that word. To explain how reading behavior on a fixated target word can be primarily influenced by properties of a different, unfixated (i.e., parafoveal preview) word we turn to an explanation suggested by Schotter et al. (2014; see also Schotter et al., 2015) regarding the relationship between linguistic processing and eye movement programming in first-pass reading as described by the framework of the E-Z Reader model (e.g., Reichle, 2011). The full details of the model are beyond the scope of this paper, but it is sufficient for the following discussion to know that both word identification and saccade programming are divided into two stages in the model. With respect to word identification, the completion of the first stage (L1) triggers both the second stage of word identification (L2) and the first stage of saccade programming (M1) away from that word. The completion of the second stage of word identification causes attention to shift to the upcoming word and for the first stage of word identification to start for that word. Therefore, covert attention and eye movement control are often dissociate in the model, with the shift of attention toward a word preceding the eye movement toward it. With respect to the saccade programming stages, the first stage is labile, meaning that the saccade program can be cancelled and a new one can be programmed whereas the second stage (M2) is non-labile, meaning that it cannot be cancelled.

The above description of the E-Z Reader model has remained mostly unchanged since it was first proposed (Reichle, Pollatsek, Fisher, & Rayner, 1998). The idea regarding preview benefit effects introduced by Schotter et al. (2014) is that there is a subset of cases (8% of the time in the simulation of Schotter's (2013) data that they conducted) in which L1 for the upcoming preview word completes and the model enters the L2 stage for that word while the eyes are still fixating the prior word. As noted by Schotter et al. (2015), a consequence of the completion of the L1 stage is not only the start of the L2 stage, but also the initiation of a saccade program (M1). If the completion of the L1 stage that initiates the M1 stage for the upcoming word occurs during the current saccade program's labile (M1) stage, then the saccade to the preview/target is cancelled and the system programs a skip instead (as noted above, word skipping is uncontroversially influenced by properties of the preview; Rayner, 2009). If, however, completion of the L1 stage that initiates the M1 stage for the upcoming word occurs during the current saccade program's non-labile (M2) stage, the system cannot skip the preview word and instead pre-initiates the upcoming saccade program (i.e., from the preview/target word to the following word) prior to fixation on the target word. This feature of parallel saccade programs was introduced in Morrison's (1984) model of oculomotor control in reading and was incorporated into the E-Z Reader framework. This pre-initiation shortens the subsequent fixation duration on the target word and appears as a preview benefit effect. Thus, there are some fixations on the target whose duration is determined by properties of the preview rather than the target because the saccade toward that word was in the non-labile (M2) stage when the completion of the L1 stage for that word completed. Importantly, because the completion of L1 had happened while the eyes were still fixating the prior word, the completion of L1 (and therefore initiation of M1 and concomitant shortening of the subsequent fixation duration) was based on the preview, rather than the target word.

This account also predicts that fixation durations on the target word should be lengthened if the L1 stage does not complete early enough during parafoveal preview to cause a skip or trigger pre-initiation of the upcoming saccade (i.e., if it is a nonword as in many prior boundary paradigm experiments). In this case, more information is needed and the target word must be fixated and processed to some degree in order to initiate saccade programming, leading to a long fixation on the word. In the model, the duration of the L1 stage is determined by three lexical characteristics: word length, frequency, and word-form cloze predictability. However, in the present study, we observed longer first pass times on actual words (i.e., as opposed to nonwords) when the preview was an implausible word. At the moment, this effect cannot be explained within the E-Z Reader framework because plausibility is considered a post-lexical characteristic and does not exert an influence on reading behavior until after the L1 stage. Without conducting simulations with the model it is not possible make concrete predictions, but to accommodate this finding we can imagine (at least) two possibilities. First, plausibility of the preview may also be a feature of words that influences L1 and could be incorporated as an additional parameter in determining its duration. Second, plausibility of the preview word may be processed shortly after L1 (after fixation on the target word) and, at that point, inhibits or cancels the saccade program, which would similarly predict longer fixation durations. Either of these accounts could explain why the implausible unrelated preview condition yielded longer first-pass fixation durations than any of the plausible preview conditions even though it was similar in length and frequency to the other preview words, and why it yielded the lowest proportion of non-target responses in the questions in Experiment 2.

One note we must make with respect to preview benefit effects from the prior literature is that some studies have actually found significant preview benefit in first-pass fixation duration measures from orthographically related nonword previews (e.g., Rayner et al., 1986; Drieghe et al., 2005). As mentioned in the introduction, the explanation for the effects was by means of integration across saccades, an account against which we argue here. These data may be accommodated by the account we describe above by means of misperception of the nonword preview for a similar real word form (see Slattery, 2009 for a discussion of misperception). Particularly, the nonword preview could have been misperceived as the visually/orthographically similar target word, which in the context of the sentences used in those studies was a plausible and sensible word form. This seems to be a reasonable account since visual acuity is poor in the parafovea and especially for early studies that used low quality computer monitors that would make it difficult to precisely determine letter identities (see Drieghe et al., 2005 for a similar argument about monitor quality).

The above account only describes eye movement behavior during first-pass reading. The total time and regression data might be better accommodated by an integration account since the target information would have had more time to be processed and the relationship between it and the preview might therefore be more pertinent to eye movement behavior. We must, however, be more specific in what we mean by “integration” in this case. In fact, the E-Z Reader framework incorporated an integration stage (Reichle, Warren, & McConnell, 2009), which refers to the post-lexical integration of a given word with the sentence context, rather than the trans-saccadic integration of the preview and the target. Perhaps the idea of “memory codes” suggested by Pollatsek et al. (1992) operates on a longer time scale than across saccades and at a higher linguistic level than between the individual word forms of the preview and target. That is, it is possible that the total time data in our experiments could be explained by the reader entertaining two simultaneous representations of the event being described by the two versions of the sentence, one including the preview word and the other including the target word. Indeed, prior research has suggested that readers maintain uncertainty about the identities of previously read words until they can be resolved by subsequent input (Levy, Bicknell, Slattery, & Rayner, 2009). This notion could easily extend to two representations of a word or described event that the reader has encountered—one prior to fixation and the other upon direct fixation. To the extent that these two representations are the same (i.e., when the words are synonyms) or very similar (i.e., when they are antonyms) not much distinction or adjudication between the events is necessary in order for the reader to settle on a reasonable general understanding. However, in the plausible unrelated preview condition this is not the case and two unrelated but equally plausible events are now both entertained and the reader needs to select one of them. This would lead the reader to make a regression and check which word was actually there, increasing total time and leading to the elimination of the early preview benefit that was afforded by the contextual fit of the preview, despite the fact that the norming procedures showed that the complete sentences with the plausible unrelated word were still perfectly sensible.

The lack of a preview benefit in total time for the plausible unrelated condition, which contrasted with the significant preview benefit in first-pass measures for that condition, was observed in both experiments. In contrast, two different patterns of preview benefit in total time were observed for the antonym condition between the two experiments. This difference could be explained by the above account because of the different comprehension demands imposed by the nature of the questions in the two experiments. In the first experiment, questions probed a general understanding of the sentence (i.e., did not distinguish between the preview/target words) and only occurred on 26% of the trials. In contrast, in the second experiment questions occurred after every sentence and, in addition to general comprehension questions on non-display change trials, included detailed comprehension questions that probed whether the reader had encoded the preview or the target. It is likely that the increased demand on the comprehension system to have a precise representation of the sentence made the readers more cautious and less willing to accept an incomplete or ambiguous understanding of the event.

The account of early preview effects based on the timing of parafoveal word identification relative to saccade programming predicts that the patterns of data observed in these studies are due to a mixture of cases—skip trials, shortened fixations that are due to pre-initiated saccades influenced primarily by the parafoveal preview, and long fixations influenced primarily by the foveal target. Thus, the preview benefits observed in all of the plausible preview conditions in the studies reported here are likely to have a greater proportion of shortened fixations than the implausible preview conditions. Because this is a probabilistic account, future research will be necessary to determine on an individual trial basis whether a fixation should be considered a shortened fixation or a long fixation, given variability across both subjects and items in terms of fixation durations. Using the computational models of oculomotor control in reading, with which we can probe the time course of word identification stages relative to saccade programming stages, could be quite useful in simulating and estimating these probabilities, which can only be inferred from the empirical data. Relatedly, recent research has shown that the skill level of the reader affects the pattern of semantic (Veldre & Andrews, 2016a) and plausibility (Veldre & Andrews, 2016b) preview benefits observed in boundary paradigm studies. Thus, modeling work simulating different proportions of shortened and long fixation cases, as well as individual differences across readers' skill levels, will be useful in supporting or disconfirming these hypotheses.

The account of the later reading time data via competing sentence representations is admittedly quite speculative and future work will be needed to more precisely determine the reader's internal representation of the event being described in the text, particularly with respect to skipping and display change paradigms in which there may be two parallel events being represented. One thing that is clear from the current data is that initial eye movement behavior on a word, not only the likelihood of skipping but also fixation durations on the word when it is not skipped, can be influenced by properties of the parafoveal preview (e.g., its plausibility) irrespective of its relationship to the target, as demonstrated by the first-pass reading data in both Experiments 1 and 2. However, the ultimate understanding of the sentence is most likely to be based on the target word if that has been fixated either during first pass reading or after a regression, as demonstrated by the comprehension data in Experiment 2. This dissociation suggests that the engine driving the eyes forward in the text is a quick and relatively risky local word identification processes, to a large part determined by properties of the parafoveal preview. However, the ultimate understanding of the sentence is the consequence of a more sluggish and careful process that requires regressions to ensure accurate understanding and which is mostly determined by fixated target information and the relationship between the preview and target in the case in which they are different.

Acknowledgements