Abstract

Rationale

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has an unknown etiology; however, cardiovascular risk factors are associated with a higher incidence of AD. A defining feature of endothelial dysfunction induced by cardiovascular risk factors is reduced bioavailable endothelial nitric oxide (NO). We previously demonstrated endothelial NO acts as an important signaling molecule in neuronal tissue.

Objective

We sought to determine the relationship between the loss of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and tau phosphorylation in neuronal tissue.

Methods and Results

We utilized eNOS knockout (−/−) mice as well as an AD mouse model, APP/PS1 that lacked eNOS (APP/PS1/eNOS−/−) to examine expression of tau kinases and tau phosphorylation. Brain tissue from eNOS−/− mice had statistically higher ratios of p25/p35, indicative of increased cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) activity as compared to wild type (n=8, P<0.05). However, tau phosphorylation was unchanged in eNOS−/− mice (P>0.05). Next, we determined the role of NO in tau pathology in APP/PS1/eNOS−/−. These mice had significantly higher levels of p25, a higher p25/p35 ratio (n=12–14, P<0.05) and significantly higher Cdk5 activity (n=4, P<0.001). Importantly, APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice also had significantly increased tau phosphorylation (n=4–6, P<0.05). No other changes in amyloid pathology, antioxidant pathways, or neuroinflammation were observed in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice as compared to APP/PS1 mice.

Conclusions

Our data suggests that loss of endothelial NO plays an important role in the generation of p25 and resulting tau phosphorylation in neuronal tissue. These findings provide important new insights into the molecular mechanisms linking endothelial dysfunction with the pathogenesis of AD.

Keywords: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase, tau, Cdk5, Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrovascular disease

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease is a huge social and economic burden affecting over 5 million people in the U.S.1. While a definitive cause of AD is unknown, numerous cardiovascular risk factors are associated with higher incidence of AD2, 3. A common feature of these cardiovascular risk factors is endothelial dysfunction. A defining characteristic of endothelial dysfunction is reduced bioavailability of endothelial nitric oxide (NO)4, 5. We previously demonstrated that endothelial NO acted as an important signaling molecule in neuronal tissue6, 7. Loss of endothelial NO led to several AD-related pathologies, including: increased amyloid precursor protein (APP) expression and amyloidogenic processing6, 7 and cognitive impairment in aged eNOS+/− and eNOS−/− mice7, 8. Based on these observations we hypothesized that endothelial NO might also affect the phosphorylation of tau. Tau pathology is a hallmark of AD, where it becomes hyperphosphorylated and dissociates from the microtubules to form the primary component of neurofibrillary tangles. Several kinases are implicated in the phosphorylation of tau, primarily cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) 5 and glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) 3β9, 10. Therefore, we sought to determine the role of endothelial NO in modulating kinase expression and tau phosphorylation in brain tissue of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) knockout mice (eNOS−/−) as well as in an AD mouse model that also lacked eNOS.

METHODS

Animals

Nos3tm1Unc/J (eNOS−/−), stock #002684, and C57BL/6 (wild-type) mice, stock #000664, were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). APPswe, PSEN1dE9+/− (APP/PS1) mice on the C57BL/6 genetic background were originally purchased from Jackson laboratory as stock # 005864. Subsequently, APP/PS1 mice were transferred from Jackson Laboratory to Mutant Mouse Resource & Research Centers (MMRRC) and mice were purchased from MMRRC as stock #034832-JAX. eNOS−/− mice were bred with C57BL/6 mice to generate eNOS+/− mice. To generate wild type, APP/PS1, and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice used in experiments, eNOS+/− (female) and APP/PS1/eNOS+/− (male) mice were bred in house. The average breeding pair has 2–3 litters with viable pups and these resultant litters average 4–5 pups. We wish to point out that APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice are found in very small numbers in the resulting litters, approaching 1 mouse in every 22–25 mice born. Male mice were sacrificed at 4–5 months of age by a lethal dose of pentobarbital.

A detailed methods section is provided online at http://circres.ahajournals.org in the Online Supplement and includes detailed methods regarding: genotyping/PCR, tissue collection, confocal microscopy, Western blotting, ELISA for Aβ, and statistical analysis which are as previously described6, 7.

RESULTS

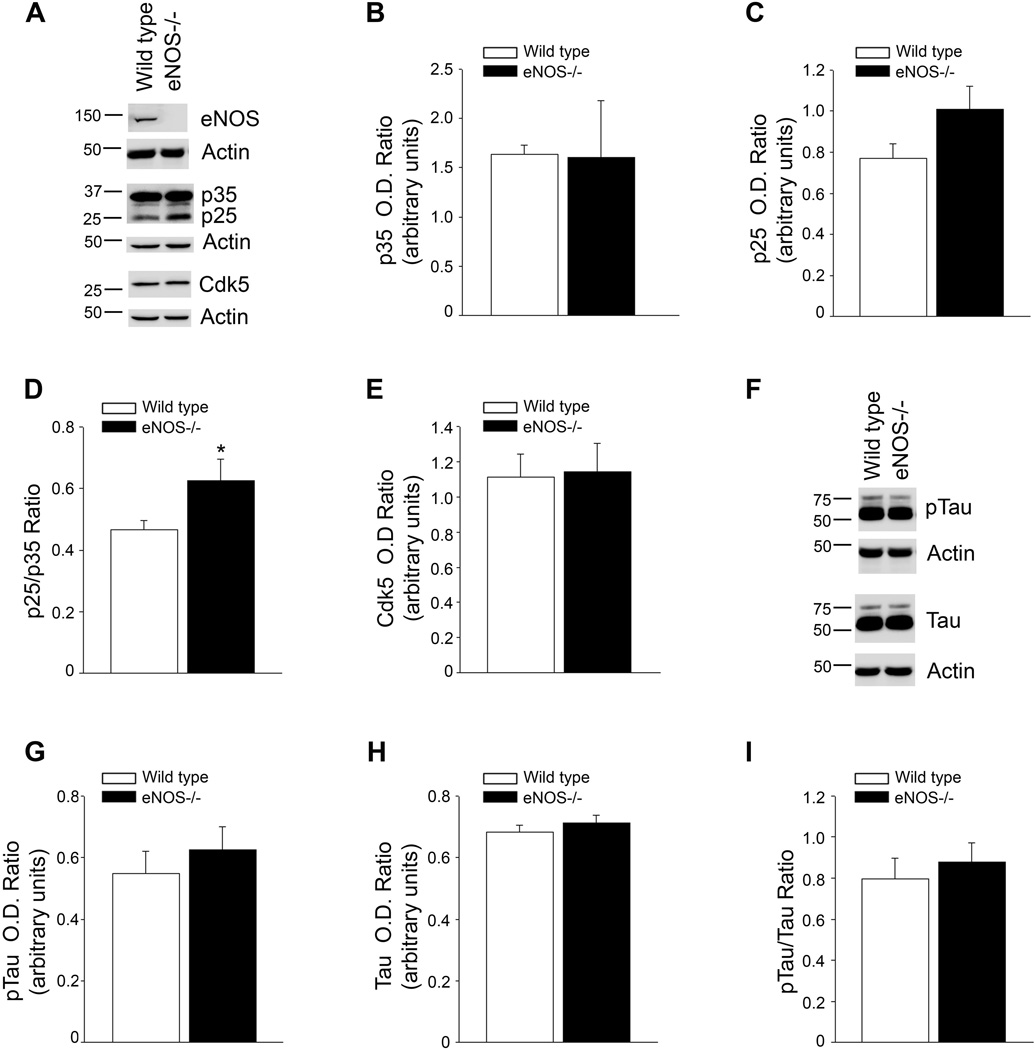

The ratio of p25/p35 is significantly higher in the brains of eNOS−/− mice

We sought to determine if chronic loss of endothelial NO affected protein kinases known to be involved in the phosphorylation of tau. First, we examined the levels of Cdk5 and its activators p35 and p25. While there was no difference between protein levels of Cdk5 or p35, p25 tended to be increased in the brain tissue from eNOS−/− mice as compared to wild type mice (Fig. 1A–E). Importantly, the increased ratio of p25/p35, an established index of increased Cdk5 activity, was significantly higher in the eNOS−/− brain tissue as compared to wild type (Fig. 1D; P<0.05).

Figure 1.

p25/35 ratio is significantly higher in the brain tissue of eNOS−/− mice as compared to wild type although tau phosphorylation is unchanged. A, Brain tissue from 4 month old wild type and eNOS−/− mice was analyzed by Western blot. A representative image is shown. Densitometric analysis for B, p35, C, p25, D, p25/p35 ratio, and E, Cdk is shown. Data is presented as relative mean O.D. ± SEM (n = 8 animals per background, *P<0.05 from wild type). F, Brain tissue from 4 month old wild type and eNOS−/− mice was analyzed by Western blot. A representative image is shown. Densitometric analysis of G, pTau, H, tau, and I, pTau/tau ratio, is shown. Data is presented as relative mean O.D. ± SEM (n=8 animals per background).

We also examined the levels of GSK3β and Akt, two other kinases involved in aberrant tau phosphorylation. There were no differences observed in their expression or phosphorylation suggesting their expression and phosphorylation in the brain are unaffected by loss of eNOS (Online Fig. I).

No alteration in tau phosphorylation in eNOS−/− brain tissue

To determine if the increased p25/p35 ratio led to increased tau phosphorylation, we measured protein levels of tau and phosphorylated tau (pTau) in the brains of wild type and eNOS−/− mice. No differences were observed in tau or pTau levels in brain tissue (Fig. 1F–I; P>0.05).

Characterization of APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice

There was no difference in body weight between wild type, APP/PS1, or APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice (Online Table I). Systolic blood pressure was significantly elevated in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice as compared to both wild type and APP/PS1 mice (Online Table I; P<0.001 from wild type, P<0.01 from APP/PS1). Next, we examined circulating levels of glucose, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides (Online Table I). Of these, only triglycerides were significantly different between the groups. Triglycerides were significantly higher in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice as compared to both wild type and APP/PS1 mice (Online Table I; P<0.01 from wild type, P<0.05 from APP/PS1).

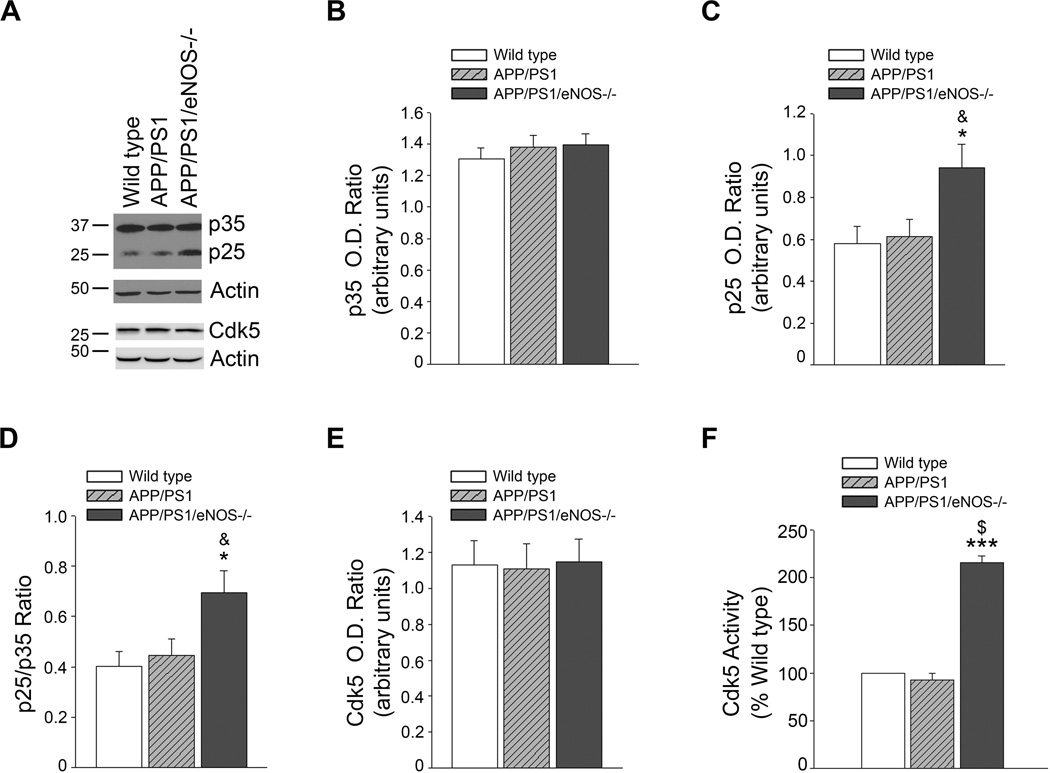

p25 and tau phosphorylation in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− brain tissue

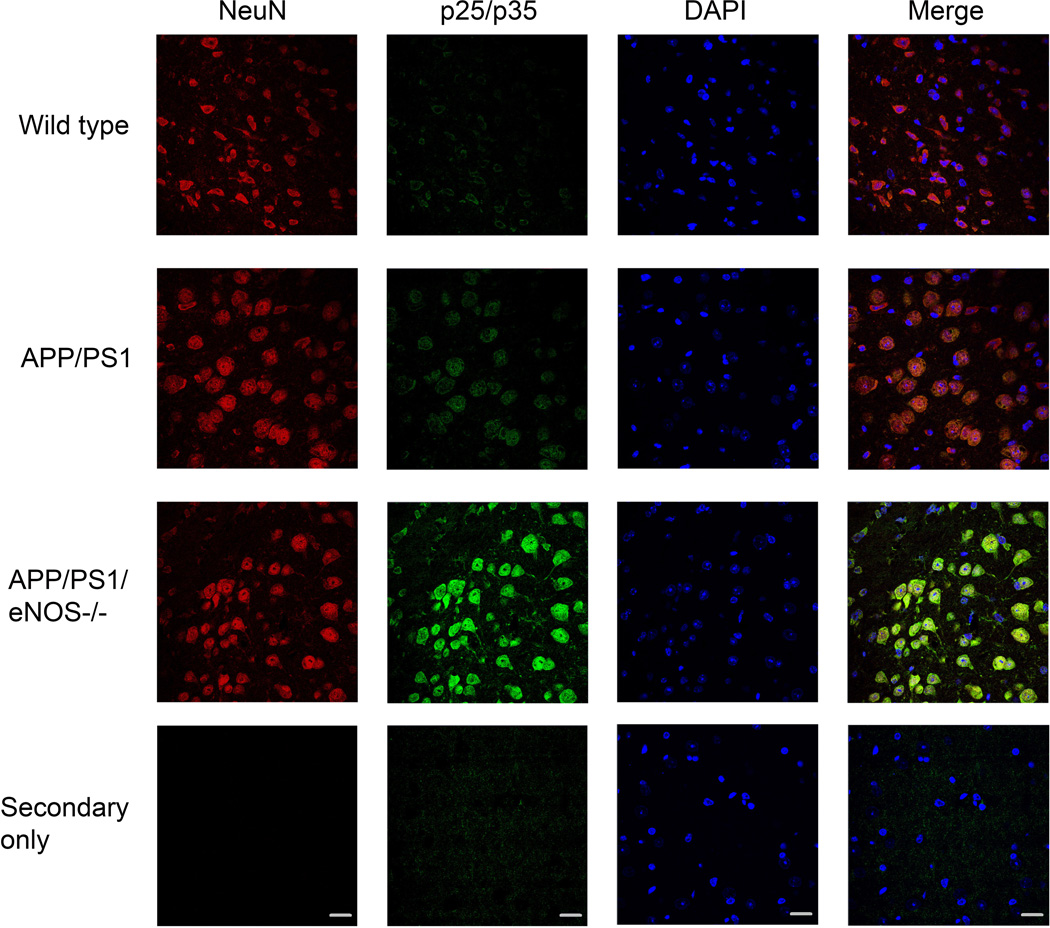

We examined protein expression of p35, p25, and Cdk5 by Western blot. p25 protein levels and p25/p35 ratio were significantly higher in the brains of APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice as compared to both wild type and APP/PS1 (Fig. 2A–D; *P<0.05 from wild type; & P<0.05 from APP/PS1). Importantly, p25 and the p25/p35 ratio were not significantly different in the APP/PS1 brain tissue as compared to wild type (Fig. 2). Notably, Cdk5 enzyme activity was significantly higher in Cdk5 isolated from APP/PS1/eNOS−/− brain tissue as compared to Cdk5 from wild type and APP/PS1 tissue (Fig 2F; P<0.001 from wild type and APP/PS1). Immunohistochemical analysis of p25/p35 showed increased immunoreactivity in both the cortex (Fig. 3) and hippocampus (data not shown) of APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice as compared to wild type and APP/PS1. Furthermore, expression of p25/p35 (Fig. 3) and Cdk5 (Online Fig. II) was mainly observed in neuronal tissue as demonstrated by the colocalization with NeuN, a neuronal marker.

Figure 2.

p25 and p25/35 ratio are significantly increased in the brain tissue of APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice as compared to both APP/PS1 and wild type mice. A, Brain tissue from 4–5 month old wild type, APP/PS1, and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice was analyzed by Western blot using p35/p25, Cdk5, and Actin (loading control) antibodies. A representative image is shown. Densitometric analysis for B, p35, C, p25, D, p25/p35 ratio, and E, Cdk is shown. Data is presented as relative mean O.D. ± SEM (n = 12 to 14 animals per background; *P<0.05 from wild type, & P<0.05 from APP/PS1). F, Cdk5 was isolated from brain tissue of 4 month old wild type, APP/PS1, and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice. Cdk5 enzyme activity was then measured using the ADP-Glo kinase activity assay from Promega. Data is presented as mean % of wild type activity ± SEM (n=4 animals per background; ***P<0.001 from wild type and $P<0.001 from APP/PS1).

Figure 3.

p25/p35 immunoreactivity was increased in the cortex of APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice and colocalized with the neuronal marker, NeuN. Fixed tissue sections from the brains of wild type, APP/PS1, and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− animals were immunolabeled with anti-p25/p35 (with an anti-rabbit IgG FITC secondary) and anti-NeuN Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated primary. 4’,6’-diamiddino-2-phenylindole dilactate (DAPI) to visualize nuclei. Representative images of the cortex are shown. Magnification 40×; bar is representative of 20 µm.

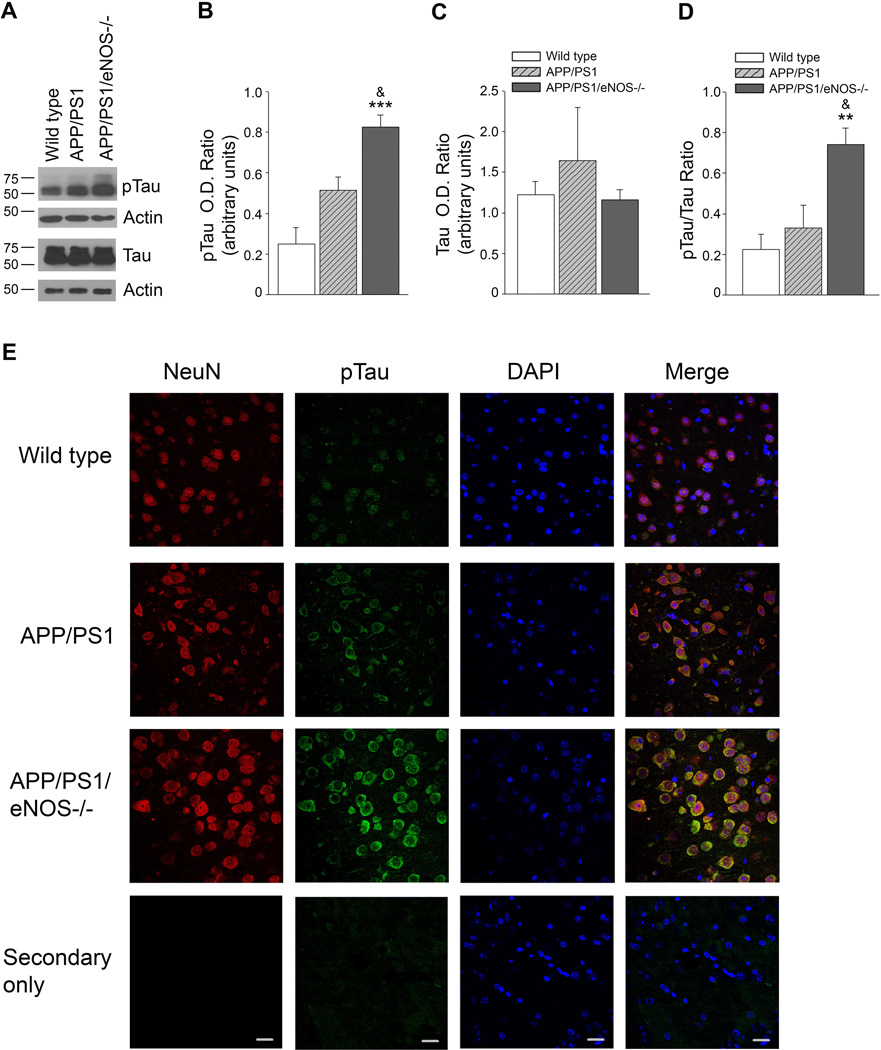

Levels of total tau was unchanged between wild type, APP/PS1, and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice (Fig. 4A, C) while protein levels of pTau and the ratio of pTau/Tau were significantly increased in the brains of the APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice as compared to the other mice (Fig. 4A, B, D; *** P<0.001, **P<0.01 from wild type; & P<0.05 from APP/PS1). However, while pTau tended to be higher in APP/PS1 (P>0.05) the pTau/tau ratio were not different between wild type and APP/PS1 mice (Fig. 4A–D). Immunohistochemical analysis of pTau showed cellular localization within neurons as indicated by colocalization with the neuronal marker. Increased pTau immunoreactivity was observed in the cortex (Fig. 4E) and hippocampus (data not shown) of APP/PS1/eNOS−/− as compared to wild type and APP/PS1. We did perform immunohistological examinations of brain tissue using an antibody for neurofibrillary tangles but did not observe any evidence of these tangles in the brain sections from APP/PS1 or APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice at the 3–4 months of age we examined (data not shown).

Figure 4.

pTau and pTau/Tau ratio are significantly increased in the brain tissue of APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice as compared to both APP/PS1 and wild type mice and pTau is localized to neuronal tissue. A, Brain tissue from 4–5 month old wild type, APP/PS1, and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice was analyzed by Western blot. A representative image is shown. Densitometric analysis for B, pTau, C, tau, D, pTau/tau ratio, and is shown. Data is presented as relative mean O.D. ± SEM (n = 4 to 6 animals per background; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 from wild type, & P<0.05 from APP/PS1). E, Fixed tissue sections from the brains of wild type, APP/PS1, and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− animals were immunolabeled with anti-pTau (with an anti-rabbit IgG FITC secondary) and anti-NeuN Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated primary. 4’,6’-diamiddino-2-phenylindole dilactate (DAPI) to visualize nuclei. Representative images of the cortex are shown. Magnification 40×; bar is representative of 20 µm.

While phosphorylated GSK3β and the ratio of phosphorylated GSK3β/GSK3β tended to be higher in the brains of APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice, they did not reach statistical significance (Online Fig. III; P>0.05).

Expression and amyloidogenic processing of APP in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice

We examined protein levels of APP and β-site APP cleaving enzyme (BACE)1 in the brain tissue of wild type, APP/PS1, and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice. There was a significant increase in APP protein expression in APP/PS1 and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice as compared to wild type (Online Fig. IV A–B; P<0.05 as compared to wild type) and an increase in BACE1 protein levels in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− as compared to wild type (Online Fig. IV C; *P<0.05); however, there was no difference between APP or BACE1 protein levels between APP/PS1 and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice (Online Fig. IV).

We measured circulating levels of beta amyloid (Aβ)40 and Aβ42 in these mice and found no significant differences between APP/PS1 and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice (data not shown, n=4 to 6 animals per background; P>0.05). Furthermore, when we examined brain tissue levels of soluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 we found no differences (data not shown, n=4 to 6 animals per background; P>0.05).

NOS isoforms, COX pathway, antioxidant systems, and microglia activation

To determine if there were compensatory changes in other important endothelial pathways, we examined protein levels of inducible (i) NOS, neuronal (n)NOS, and cyclooxygenase (COX)-1, COX-2, and prostacyclin synthase (PGI2S). Importantly, iNOS and nNOS protein levels were unchanged by the loss of eNOS (Online Fig. V). Furthermore, levels of COX enzymes and PGI2S were not altered in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice (data not shown, n=6 to 8 animals per background, P>0.05). Levels of the major antioxidant enzymes were unchanged between wild type, APP/PS1, and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice (Online Fig. VI). Furthermore, levels of 2-hydroxyethiudium, a measure of superoxide anion, were not different in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice (Online Fig. VI F). Neuronal and astrocyte markers, NeuN and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), respectively, were unchanged (data not shown, n=4 to 6 animals per background, P>0.05). Importantly, microglial markers, cluster of differentiation (CD)68, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II, and ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule (Iba)-1 were not different between the 3 groups of mice (Online Fig. VII). Levels of IL-1α, as measured by ELISA, were not altered in the brains of APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice (Online Fig. VII). Lastly, no differences were seen between wild type, APP/PS1 or APP/PS1/eNOS−/− brain tissue in a proinflammatory array which examined 40 cytokines (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our results are significant as they continue to demonstrate the importance of endothelial dysfunction as a plausible factor in the development of AD pathology. We demonstrate for the first time that loss of endothelial NO leads to alterations in neuronal p25, an aberrant activator of the tau kinase, Cdk5. Indeed, in our APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice increased p25 is accompanied by statistically higher enzymatic activity of Cdk5 and increased levels of pTau. It is important to note that this effect appears specific to loss of endothelial NO in the AD mouse model. While we cannot completely rule out that alterations in NO produced by iNOS and nNOS may contribute to the upregulation of Cdk activity and increased pTau levels, these seem unlikely. First, in our previous studies, we reported that the loss of endothelial NO in eNOS−/− mice resulted in decreased microvascular levels of NOx while overall brain NOx levels were unchanged6 which suggests that loss of eNOS did not lead to compensatory changes in nNOS or iNOS produced NO within the brain tissue. Importantly, loss of eNOS alone, as seen in the eNOS−/− mice, was sufficient to increase generation of p25. Second, a search of the literature did not return any results suggesting iNOS or nNOS protein levels or enzyme activity were increased in young APP/PS1 mice. In addition, we report that expression of iNOS and nNOS is not elevated in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice thereby, reinforcing our conclusion that loss of eNOS function is primarily responsible for elevated phosphorylation of pTau. Lastly, we did report increased systolic blood pressure in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice and therefore cannot completely rule out hypertension as a contributing factor in the changes we report.

It is established that tau is predominantly expressed in neurons and we were not able to detect tau protein in cerebral microvessels or in cultured brain microvascular endothelial cells (unpublished observation). In addition, our immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated colocalization of pTau with the neuronal marker, NeuN. Cdk5 and GSK3β are the most relevant kinases involved in tau phosphorylation9, 10. Increased Cdk5 activity is associated with hyperphosphorylation of tau, paired helical fragments and neurite death11, 12. The increased pTau we observed in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice appears to be mediated by increased activity of Cdk5 as loss of endothelial NO did not lead to changes in other tau kinases, namely GSK3β and Akt. While phosphorylated GSK3β tended to be higher in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice, this phosphorylation site is an inhibitory site which would lead to decreased GSK3 β activity and thus is not likely to be responsible for the increased pTau we see. Indeed, we report here for the first time, that loss of eNOS led to an increased p25/p35 ratio. It is reported that increased p25/p35 ratio, caused by increased generation of p25 by calpain, leads to an aberrant activation of Cdk5 promoting tau phosphorylation and neurodegeneration13, 14. Importantly, our observed increased in p25 and p25/p35 ratio was accompanied by increased Cdk5 enzymatic activity in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice. Notably, in the present study increased tau phosphorylation was seen in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice and not in eNOS−/− mice or APP/PS1 mice as compared to age-matched wild type mice at 4 months of age. This suggests there may be a synergistic effect between the loss of eNOS and amyloid alterations present in the APP/PS1 mouse resulting in very early appearance of tau pathology. Indeed, prior studies established that pTau was detected in adult APP/PS1 mice, only at 7–10 months of age15, 16.

Tau acts to stabilize microtubules within neurons. Hyperphosphorylation of tau can cause Tau to dissociate from the microtubules thereby leading to neurofibrillary tangle formation and eventually neuronal dysfunction and death17. We did not observe neurofibrillary tangles in the 4 month old APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice; however, the earlier appearance of increased pTau in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− as compared to what is reported in the literature for APP/PS1 mice suggests that the loss of endothelial NO may accelerate the pathology timeline in these mice. Future studies will need to be performed to document the time course of pathological and cognitive alterations in these mice as they age.

There are two mechanisms by which NO can mediate signaling changes: cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and S-nitrosylation. Treatment of Tg2576 mice with sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor which increases levels of cGMP, led to decreased Cdk5 activity as well as GSK3β activity18. Furthermore, it is reported that S-nitrosylation can inhibit calpain activity, an enzyme responsible for cleavage of p35 to p2519, 20. Won et al (2015) reported that S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) treatment of purified calpain protein inhibited its activity21. Consistent with our findings, Annamalai et al (2015) demonstrated that treatment of APP/PS1 mice with GSNO led to decreased calpain-mediated cleavage of p35 and decreased Cdk5 activity22. Taken together, these data suggest that loss of endothelial NO may alter the activity of calpain thus leading to increased Cdk5 activity. While it is reported that several other stimuli, such as: oxidative stress, Aβ exposure, and neuroinflammation23–25 can all lead to activation of calpain we did not observe any changes in Aβ levels, the antioxidant enzyme system or superoxide anion production, or inflammatory markers between APP/PS1 and APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice making these unlikely sources of calpain activation.

The results in this study provide novel findings regarding yet another role for vascular dysfunction in AD-related pathology. We report, that loss of endothelial NO, a primary feature of endothelial dysfunction, leads to increased p25 production. Importantly, increased p25, increased p25/35 ratio is an established mechanism responsible for elevated Cdk5 activity13, 14 and indeed, Cdk5 enzyme activity was significantly higher in APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice. Furthermore, loss of endothelial NO in APP/PS1, an AD mouse model, led to statistically higher phosphorylation of tau. Our data thus provide significant evidence supporting the role of endothelial NO in the preservation of brain health. These findings also have significant implications for the development of therapies designed to treat and prevent mild cognitive impairment and AD.

Supplementary Material

Novelty & Significance.

What Is Known?

Cardiovascular risk factors are associated with a higher incidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

A common feature of cardiovascular risk factors is endothelial dysfunction, specifically, a loss of bioavailable endothelial nitric oxide (NO).

Hyperphosphorylated tau is the primary component of neurofibrillary tangles, one of the hallmark pathologies of AD.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) deficient (eNOS−/−) mice display increased levels of p25, an aberrant activator of cyclin dependent kinase (Cdk)5 which is one of the primary kinases responsible for tau hyperphosphorylation, and a statistically higher p25/p35 ratio.

We generated a novel AD mouse model that also lacks eNOS, APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice.

APP/PS1/eNOS−/− mice displayed increased p25, p25/p35, Cdk5 enzyme activity, and hyperphosphorylated tau.

Cardiovascular risk factors are associated with a higher incidence of AD. Loss of bioavailable endothelial NO is a common feature of these risk factors. The results of this study provide evidence that loss of endothelial NO leads to increased tau phosphorylation, a major mechanism responsible for the development of neurodegeneration in AD. Our findings identify a new role for endothelial NO in the pathogenesis of AD. Presented results support the concept that preservation of the endothelial NO pathway is a therapeutic target in the prevention and treatment of AD.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL-111062 and HL-131515, the Mayo Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (Z.S.K.), American Heart Association (AHA) Postdoctoral Fellowship (AHA# 12POST8550003, S.A.A) and AHA Scientist Development Award (AHA# 14SDG20410063, S.A.A), and the Mayo Foundation.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- NO

nitric oxide

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- GSK3β

glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- Cdk5

cyclin-dependent kinase 5

- pTau

phosphorylated tau

- eNOS−/−

eNOS knock-out/deficient

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- Aβ

beta amyloid

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- BACE1

β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- nNOS

nitric oxide synthase

- COX-1

cyclooxygenase-1

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- PGI2S

prostacyclin synthase

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- CD68

cluster of differentiation 68

- MHC II

major histocompatibility complex II

- Iba-1

ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the united states (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778–1783. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faraci FM. Protecting against vascular disease in brain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H1566–H1582. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01310.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iadecola C. The overlap between neurodegenerative and vascular factors in the pathogenesis of dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:287–296. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dudzinski DM, Igarashi J, Greif D, Michel T. The regulation and pharmacology of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2006;46:235–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atochin DN, Huang PL. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase transgenic models of endothelial dysfunction. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460:965–974. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0867-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin SA, Santhanam AV, Katusic ZS. Endothelial nitric oxide modulates expression and processing of amyloid precursor protein. Circulation research. 2010;107:1498–1502. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Austin SA, Santhanam AV, Hinton DJ, Choi DS, Katusic ZS. Endothelial nitric oxide deficiency promotes alzheimer's disease pathology. Journal of neurochemistry. 2013;127:691–700. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan XL, Xue YQ, Ma T, Wang X, Li JJ, Lan L, Malik KU, McDonald MP, Dopico AM, Liao FF. Partial enos deficiency causes spontaneous thrombotic cerebral infarction, amyloid angiopathy and cognitive impairment. Molecular neurodegeneration. 2015;10:24. doi: 10.1186/s13024-015-0020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanger DP, Hughes K, Woodgett JR, Brion JP, Anderton BH. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 induces alzheimer's disease-like phosphorylation of tau: Generation of paired helical filament epitopes and neuronal localisation of the kinase. Neuroscience letters. 1992;147:58–62. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu F, Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I, Gong CX. Involvement of aberrant glycosylation in phosphorylation of tau by cdk5 and gsk-3beta. FEBS letters. 2002;530:209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plattner F, Angelo M, Giese KP. The roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and glycogen synthase kinase 3 in tau hyperphosphorylation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:25457–25465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Twomey C, McCarthy JV. Presenilin-1 is an unprimed glycogen synthase kinase-3beta substrate. FEBS letters. 2006;580:4015–4020. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahlijanian MK, Barrezueta NX, Williams RD, Jakowski A, Kowsz KP, McCarthy S, Coskran T, Carlo A, Seymour PA, Burkhardt JE, Nelson RB, McNeish JD. Hyperphosphorylated tau and neurofilament and cytoskeletal disruptions in mice overexpressing human p25, an activator of cdk5. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:2910–2915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040577797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrick GN, Zukerberg L, Nikolic M, de la Monte S, Dikkes P, Tsai LH. Conversion of p35 to p25 deregulates cdk5 activity and promotes neurodegeneration. Nature. 1999;402:615–622. doi: 10.1038/45159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos-Rodriguez JJ, Pacheco-Herrero M, Thyssen D, Murillo-Carretero MI, Berrocoso E, Spires-Jones TL, Bacskai BJ, Garcia-Alloza M. Rapid beta-amyloid deposition and cognitive impairment after cholinergic denervation in app/ps1 mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:272–285. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318288a8dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Q, Wang M, Du Y, Zhang W, Bai M, Zhang Z, Li Z, Miao J. Inhibition of c-jun n-terminal kinase activation reverses alzheimer disease phenotypes in appswe/ps1de9 mice. Ann Neurol. 2015;77:637–654. doi: 10.1002/ana.24361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuadrado-Tejedor M, Hervias I, Ricobaraza A, Puerta E, Perez-Roldan JM, Garcia-Barroso C, Franco R, Aguirre N, Garcia-Osta A. Sildenafil restores cognitive function without affecting beta-amyloid burden in a mouse model of alzheimer's disease. British journal of pharmacology. 2011;164:2029–2041. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh TJ, Tidball JG. Nitric oxide inhibits calpain-mediated proteolysis of talin in skeletal muscle cells. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. 2000;279:C806–C812. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michetti M, Salamino F, Melloni E, Pontremoli S. Reversible inactivation of calpain isoforms by nitric oxide. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1995;207:1009–1014. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Won JS, Annamalai B, Choi S, Singh I, Singh AK. S-nitrosoglutathione reduces tau hyper-phosphorylation and provides neuroprotection in rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Brain research. 2015;1624:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Annamalai B, Won JS, Choi S, Singh I, Singh AK. Role of s-nitrosoglutathione mediated mechanisms in tau hyper-phosphorylation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2015;458:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitazawa M, Oddo S, Yamasaki TR, Green KN, LaFerla FM. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation exacerbates tau pathology by a cyclin-dependent kinase 5-mediated pathway in a transgenic model of alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8843–8853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2868-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otth C, Concha II, Arendt T, Stieler J, Schliebs R, Gonzalez-Billault C, Maccioni RB. Abetapp induces cdk5-dependent tau hyperphosphorylation in transgenic mice tg2576. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2002;4:417–430. doi: 10.3233/jad-2002-4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strocchi P, Pession A, Dozza B. Up-regulation of cdk5/p35 by oxidative stress in human neuroblastoma imr-32 cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2003;88:758–765. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.