Abstract

Background

The repertoire of free-living protozoa in contact lens solutions is poorly known despite the fact that such protozoa may act as direct pathogens and may harbor intra-cellular pathogens.

Methods

Between 2009 and 2014, the contact lens solutions collected from patients presenting at our Ophthalmology Department for clinically suspected keratitis, were cultured on non-nutrient agar examined by microscope for the presence of free-living protozoa. All protozoa were identified by 18S rRNA gene sequencing.

Results

A total of 20 of 233 (8.6 %) contact lens solution specimens collected from 16 patients were cultured. Acanthamoeba amoeba in 16 solutions (80 %) collected from 12 patients and Colpoda steini, Cercozoa sp., Protostelium sp. and a eukaryotic more closely related to Vermamoeba sp., were each isolated in one solution. Cercozoa sp., Colpoda sp., Protostelium sp. and Vermamoeba sp. are reported for the first time as contaminating contact lens solutions.

Conclusion

The repertoire of protozoa in contact lens solutions is larger than previously known.

Keywords: Acanthamoeba, Keratitis, Contact lens solution, Protozoa

Background

Contact lens (CL) wearers are at risk of developing infectious keratitis [1]. In particular, the prevalence of amoebic keratitis has been shown to be significantly higher in CL wearers than in the general population living in the same geographic area [2]. Accordingly, it has been suspected that CL solution could be the source of amoeba in this situation [3]. Indeed, several studies have reported detecting amoeba in CL solutions [2]. Thus far, only amoeba of the genus Acanthamoeba have been documented in CL solutions [1, 4, 5].

Here, we prospectively search for free-living unicellular protozoa in CL solutions collected from patients with suspected keratitis, in an effort to broaden the repertoire of free-living protozoa as potential cornea pathogens.

Methods

Culture of protozoa

CL solution specimens were collected between 2009 and 2014 by CL wearers presenting to the Ophthalmology Department of the Timone Hospital in Marseille, France, for the clinical diagnosis of keratitis and corneal ulcers. Clinical criteria for diagnosis included evidence of a corneal infiltrate or corneal ulcer with underlying inflammation, which could lead to the necrosis of corneal tissue. CL solution provided by the patient was poured into a sterile can kept at room temperature for 4–24 h before it was analysed in the laboratory. The following standard protocol was used to search for protozoa. The CL solution was spread onto a non-nutrient agar plate, plated with a lawn of living Enterobacter aerogenes. The non-nutrient agar plate was incubated at 28 °C in a humidified atmosphere (contact with moistened gauze) and examined by microscope at × 4 and × 10 magnifications. Free-living protozoa were subcultured on a new non-nutrient agar plate with living E. aerogenes in order to obtain sufficient clonal populations. When the growth was sufficient, areas where protozoa were easily detected by microscope were cut and centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min. The pellet was re-suspended in 1 mL of Amoeba Page’s saline PAS (Dunstaffnage Marine Laboratory, Oban, UK) for further DNA extraction.

Culturing bacterial and fungal organisms

CL solution specimens were seeded onto 5 % sheep-blood agar (COS, bioMérieux, La-Balme-les-Grottes, France) and BCYE (Buffered Charcoal Yeast Extract, bioMérieux) and incubated at 32 °C for 10 days in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere. For the culture of yeasts and fungi, CL solution specimens were seeded onto Sabouraud agar containing chloramphenicol and gentamicin (bioMérieux), incubated at 32 °C for 10 days. All the bacterial isolates were identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS; Microflex, Bruker Biospin S.A., Wissembourg, France) as previously described [6]. Briefly, colonies detached from the agar were directly applied to a MALDI-TOF MTP 384 target plate (Bruker) in order to analyze four spots per isolate. Each spot was overlaid with 2 μL of matrix solution, a saturated solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 50 % acetonitrile mixed with 2.5 % tri-fluoracetic-acid. The matrix-sample was crystallized by air-drying at room temperature for 5 min. Measurements were performed using an Autoflex II mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik) equipped with a 337-nm nitrogen laser. Spectra were recorded in the 2–20 kDa mass range. Data were automatically acquired using AutoXecute acquisition control software. The two first raw spectra obtained for each isolate were imported into the BioTyper software, version 2.0 (Bruker Daltonik GmbH), and were analyzed by standard pattern matching (with default parameter settings) against 5625 references in the BioTyper database. When both spots yielded a score ⩾1.9, identification was complete. In this study, it was not necessary to complete accurate MALDI-TOF-MS identification of bacteria by DNA sequencing.

Molecular identification of protozoa

Total DNA was extracted using the QIAmp tissue kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (QIAGEN SA, Courtaboeuf, France). A 328-bp fragment of the 18S rRNA gene was PCR-amplified using the primers NS5/F 5′AACTTAAAGGAATTGACGGAAG3′ and NS6/R 3′GCATCACAGACCTGTTGCCTC5′ and an annealing temperature of 60 °C [7]. All amplification reactions were performed using the 2720 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Saint-Aubin, France) in a 50 μL-mixture containing 5 μL of dNTPs (2 mM of each nucleotide), 5 μL of DNA polymerase buffer (Qiagen), 2 μL of MgCL2 (25 mM), 0.25 μL HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (1.25 U) (Qiagen), 1 μL of each primer and 35.75 μL of DNAse-free water. The positive control consisted of Candida albicans DNA. Sterile distilled water was used as a negative control. PCR consisted of a 15-min initial denaturation Taq polymerase Hot-Star at 95 °C followed by 30-s denaturation at 95 °C, 30-s hybridation at 60 °C and 1-min elongation at 72 °C. After 35 cycles, extension was performed for 5 min at 72 °C. Amplified products were visualized under UV illumination with Syber Safe ® staining after electrophoresis using a 1.5 % agarose gel. PCR products were cloned by the pGEM® -T Easy Vector System Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Lyon, France). They were sequenced in both directions using the Big Dye® Terminator V1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). Original sequences have been submitted to GenBank.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

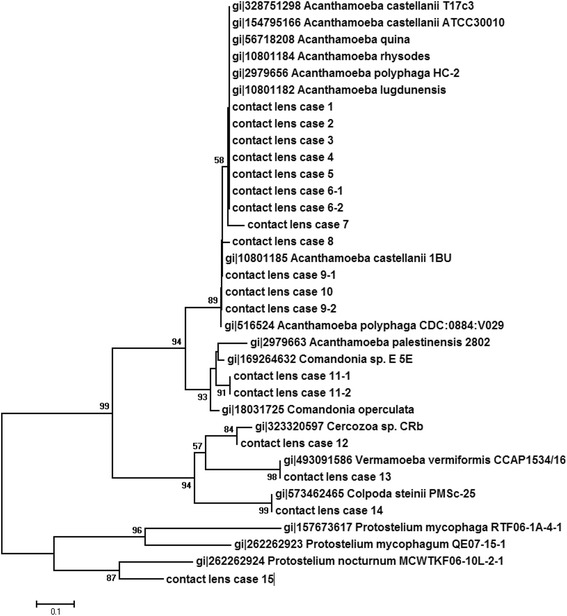

Sequencing products were resolved using an ABI PRISM 3130 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were compared with the GenBank database using the online BLAST program (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The highest percentage of sequence similarity was used to identify isolates. Sequence similarity higher than 97 % with a described species was considered to be indicative of identification at the species level. Phylogenetic analysis was established by the neighbor-joining method using MEGA5 software (www.megasoftware.net). Phylogenetic construct was based on the 18S rRNA gene sequences aligned with 52 references.

Results

Free living protozoa

A total of 20/233 (8.6 %) CL solution specimens collected between 2009 and 2014 from 16 patients, cultured at least one free-living protozoa (Table 1). Protozoa identifications were made by partial sequencing of the 18S rRNA gene and by establishing the percentage of similarity of these sequences with reference sequences. authenticated by the validity of positive and negative controls. With one exception, confident identification was obtained at the genus level only. These identifications include Acanthamoeba in 16 (80 %) solution specimens collected from 12 different patients, Colpoda steini in specimen n°14, Cercozoa sp. in specimen n°12, Protostelium sp. in specimen n°15, and an identical 99 % sequence similarity with both Hartmanella and Vermamoeba genus in specimen 13.

Table 1.

List of protozoa identified in 16 contact lens solution specimens, along with co-cultured bacteria and fungi

| Patient | CL case | Protozoa | Co-cultured bacteria | Co-cultured fungi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 1 | Acanthamoeba sp. |

Serratia liquefaciens

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

None |

| Patient 2 | 2 | Acanthamoeba sp. |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Stenotrophomonas maltophila Chryseobacterium dacguense Citrobacter freundi |

Sacrocadium kiliense |

| Patient 3 | 3 | Acanthamoeba sp. |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Chryseobacterium gleum Delftia acidovorans |

None |

| Patient 4 | 4 | Acanthamoeba sp. |

Pseudomonas fluorescens

Mycobacterium chimaera Stenotrophomonas maltophila |

None |

| Patient 5 | 5 | Acanthamoeba sp. | None | None |

| Patient 6 | 6-1 | Acanthamoeba sp. | None | None |

| 6-2 | Acanthamoeba sp. | None | None | |

| Patient 7 | 7 | Acanthamoeba sp. | None |

Candida guilliermondii

Fusarium oxyporum |

| Patient 8 | 8 | Acanthamoeba sp. |

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia

Raoultella ornithinolytica Sphingobacterium multivorium Agrobacterium tumefaciens Klebsiella terrigena Pseudomonas hibiscicola Shewanella putrefaciens Sphingobacterium siyangense |

None |

| Patient 9 | 9-1 | Acanthamoeba sp. | None | None |

| 9-2 | Acanthamoeba sp. | None | None | |

| Patient 10 | 10 | Acanthamoeba sp. |

Klebsiella pneumonia

Enterobacter cloacae Stenotrophomonas maltophila |

Candida parapsilosis

Candida lipolytica |

| Patient 11 | 11-1 | Acanthamoeba sp. |

Sphingobacterium multivorum

Aeromonas veronii Aeromonas caviae Raoutella ornitolytica Klebsiella pneumoniae |

None |

| 11-2 | Acanthamoeba sp. |

Pseudochrobactrum asaccharolyticum

Aeromonas caviae Wausteriella falsenii |

None | |

| Patient 12 | 12 | Cercozoa sp. |

Klebsiella oxytoca

Stenotrophomonas maltophila Alcaligenes xylosidans Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Candida colliculosa |

| Patient 13 | 13 | Vermamoeba sp. |

Enterobacter cloacae,

Stenotrophomonas maltophila Xanthobacter flavus Pseudomona aerouginosa Mycobacterium chelonae |

None |

| Patient 14 | 14 | Colpoda steini | None | None |

| Patient 15 | 15 | Protostelium sp. |

Alcaligenes xylosoxidans

Stenotrophomonas maltophila Pseudomonas aeruginosa Sphingomonas multivorum Aeromonas culicicola Hicrobacterium flavum Chryseobacterium hominis Microbacterium testaceum |

None |

| Patient 16 | 16-1 | Acanthamoeba sp. | Microbacterium oxydans |

Penicillium chrysogenum, Candida parapsilosis

Fusarium oxysporum |

| 16-2 | Acanthamoeba sp. | None | None |

Further phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1) confirmed these identifications and indicated that the protozoa isolated in specimen n°13 was more closely related to Vermamoeba. Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis indicated that the same Acanthamoeba was isolated in left and right contact lens solutions in patients 6, 11 and 16.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on the 18S rRNA gene sequences derived from 20 protozoan isolates taken from contact lens solutions. Bootstrap values are indicted at nodes. The bar indicates 1‰ substitutions in sequences

Bacteria and fungi

Twelve of the 20 protozoa-positive (60 %) CL specimens cultured bacteria, while eight protozoa-positive CL specimens did not. Stenotrophomonas sp. and Pseudomonas sp. were most frequently identified and found in 8/20 (40 %) specimens, followed by Klebsiella sp. in 4/20 (20 %) specimens, Aeromonas sp. in 3/20 (15 %) specimens, Chryseobacterium sp. and Sphingobacterium sp. in 2/20 (10 %) specimens and Achromobacter sp., Agrobacterium sp., Alcaligenes sp., Citrobacter sp., Delftia sp., Enterobacter sp., Microbacterium sp., Mycobacterium sp., Raoultella sp., Serratia sp., Shewanella sp. and Wautersiella sp. in 1/20 specimens. Fungi were cultured in five protozoa-positive CL specimens. Fungi included Candida guilliermondii, Candida parapsilosis, Candida lipolytica and Candida colliculosa, Fusarium oxyoprum, Sacrocadium kiliense and Penicillium chrysogenum. In three cases, several fungi were co-cultured, including P. chrysogenum, C. parapsilosis and F. oxysporum in case 16–1, C. guilliermondii and F. oxyoprum in case 7 and C. parapsilosis and C. lipolytica in case 10.

Discussion

We embarked upon a prospective study of the repertoire of free-living protozoa in the CL solutions. In this study we observed that, unsurprisingly, the vast majority of positive specimens grew an Acanthamoeba amoeba. A previous study reported 28 Acanthamoeba isolates from CL solutions, including A. lugdunensis, A. hatchettii and A. castellani [4]. Further species were later found to contaminate CL solutions of residents in Southern Korea [5]. Also, amoeba morphologically identified as A. rhysodes, A. polyphaga and A. hatchetti were reported in CL specimens of patients with clinical keratitis in Austria [8]. Here, we additionally observed that it is most likely that the same amoeba contaminates both the right and the left CL solutions. These observations are of clinical interest, as Acanthamoeba are known to cause keratitis [9–12].

However, we failed to find Colpoda sp., Protostelium sp., and Vermamoeba sp. in these CL solutions. Likewise, we found no cases of keratitis which were due to any of these three species: non-Acanthamoeba keratitis were found to be due to Valkampfia and Hartmanella amoeba [13, 14].

Amoeba, and Acanthamoeba in particular, have been shown to host so-called amoeba-resisting bacteria [15, 16], making them a source of polymicrobial keratitis which may involve the amoeba itself in addition to bacteria and viruses [17]. Several bacteria here co-cultivated with Acanthamoeba, are amoeba-resisting bacteria, including P. aeruginosa [18] Mycobacterium sp. [19–21] and Aeromonas sp. [16, 22]. We also co-cultivated several bacteria with Cercozoa sp., Vermamoeba sp. and Protostelium sp., but not with C. steini, suggesting further studies of the relationships between these protozoa and bacteria may be required.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the spectrum of protozoa contaminating CL solutions is broader than previously thought. These protozoa may also host ocular pathogens including bacteria and fungi. Some of these emerging protozoa escape the current routine detection of amoeba in clinical specimens collected from corneal lesions, underscoring the need to develop additional laboratory tools for the diagnosis of keratitis.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Unité de Recherche sur les Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales Emergentes, UM63, CNRS 7278, IRD198, Inserm 1095, 13005 Marseille, France.

Funding

This study was supported by URMITE, Aix Marseille University, Marseille, France.

Availability of data and materials

Original sequences have been submitted to GenBank.

Authors’ contributions

All of the authors contributed substantially to this study. LH and MD conceived and designed the experiments. IB and AA performed the experiments. IB, AA, LH and MD analyzed the data. MD contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. IB, AA, LH and MD wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research does not involve any patient data or any clinical specimens and hence does not require approval from the Ethics Committee.

Contributor Information

Ibtissem Bouchoucha, Email: Ibtissem.BOUCHOUCHA@ap-hm.fr.

Aurore Aziz, Email: aurore.aziz@hotmail.fr.

Louis Hoffart, Email: louis.hoffart@orange.fr.

Michel Drancourt, Phone: 33 4 91 38 55 17, Email: michel.drancourt@univ-amu.fr.

References

- 1.Gray TB, Cursons RT, Sherwan JF, Rose PR. Acanthamoeba, bacterial, and fungal contamination of contact lens storage cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:601–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.6.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar R, Lloyd D. Recent advances in the treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:434–41. doi: 10.1086/341487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Illingworth CD, Cook SD, Karabatsas CH, Easty DL. Acanthamoeba keratitis: risk factors and outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:1078–82. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.12.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SM, Choi YJ, Ryu HW, Kong HH, Chung DI. Species identification and molecular characterization of Acanthamoeba isolated from contact lens paraphernalia. Korean J Ophthalmol. 1997;11:39–50. doi: 10.3341/kjo.1997.11.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kong HH, Shin JY, Yu HS, Kim J, Hahn TW, Hahn YH, et al. Mitochondrial DNA restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and 18S small-subunit ribosomal DNA PCR-RFLP analyses of Acanthamoeba isolated from contact lens storage cases of residents in southwestern Korea. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1199–206. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1199-1206.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seng P, Drancourt M, Gouriet F, La Scola B, Fournier PE, Rolain JM, Raoult D. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:543–51. doi: 10.1086/600885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, editors. PCR protocols. San Diego: Academic; 1990. pp. 315–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walochnik J, Haller-Schober E, Kölli H, Picher O, Obwaller A, Aspöck H. Discrimination between clinically relevant and nonrelevant Acanthamoeba strains isolated from contact lens- wearing keratitis patients in Austria. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3932–6. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.3932-3936.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stapleton F, Seal DV, Dart J. Possible environmental sources of Acanthamoeba species that cause keratitis in contact lens wearers. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(Suppl 5):S392. doi: 10.1093/clind/13.Supplement_5.S392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niederkorn JY, Alizadeh H, Leher H, McCulley JP. The pathogenesis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:437–43. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(99)80047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niyyati M, Rezaie S, Babaei Z, Rezaeian M. Molecular Identification and Sequencing of Mannose Binding Protein (MBP) Gene of Acanthamoeba palestinensis. Iran J Parasitol. 2010;5:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faude F, Sünnemann S, Retzlaff C, Meier T, Wiedemann P. [Therapy refractory keratitis. Contact lens-induced keratitis caused by Acanthamoeba palestinensis] Ophthalmology. 1997;94:448–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnalich-Montiel F, Lorenzo-Morales J, Irigoyen C, Morcillo-Laiz R, López-Vélez R, Muñoz-Negrete F, et al. Co-isolation of Vahlkampfia and Acanthamoeba in Acanthamoeba-like keratitis in a Spanish population. Cornea. 2013;32:608–14. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31825697e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abedkhojasteh H, Niyyati M, Rahimi F, Heidari M, Farnia S, Rezaeian M. First Report of Hartmannella keratitis in a Cosmetic Soft Contact Lens Wearer in Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2013;8:481–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greub G, Raoult D. Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:413–33. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.2.413-433.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yousuf FA, Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Acanthamoeba castellanii of the T4 genotype is a potential environmental host for Enterobacter aerogenes and Aeromonas hydrophila. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:169. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen G, Hoffart L, La Scola B, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Ameba-associated keratitis, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1306–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1707.100826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walochnik J, Picher O, Aspöck C, Ullmann M, Sommer R, Aspöck H. Interactions of “Limax amoebae” and gram-negative bacteria: experimental studies and review of current problems. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 1998;23:273–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cirillo JD, Falkow S, Tompkins LS, Bermudez LE. Interaction of Mycobacterium avium with environmental amoebae enhances virulence. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3759–67. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3759-3767.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben Salah I, Drancourt M. Surviving within the amoebal exocyst: the Mycobacterium avium complex paradigm. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu HS, Jeong HJ, Hong YC, Seol SY, Chung DI, Kong HH. Natural occurrence of Mycobacterium as an endosymbiont of Acanthamoeba isolated from a contact lens storage case. Korean J Parasitol. 2007;45:11–8. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2007.45.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anacarso I, de Niederhäusern S, Messi P, Guerrieri E, Iseppi R, Sabia C, et al. Acanthamoeba polyphaga, a potential environmental vector for the transmission of food-borne and opportunistic pathogens. J Basic Microbiol. 2012;52:261–8. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201100097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Original sequences have been submitted to GenBank.