Abstract

Purpose

The proliferation of gene-panel testing precipitates the need for a breast cancer (BC) risk model that incorporates the effects of mutations in several genes and family history (FH). We extended the BOADICEA model to incorporate the effects of truncating variants in PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM.

Methods

The BC incidence was modelled via the explicit effects of truncating variants in BRCA1/2, PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM and other unobserved genetic effects using segregation analysis methods.

Results

The predicted average BC risk by age 80 for an ATM mutation carrier is 28%, 30% for CHEK2, 50% for PALB2, 74% for BRCA1 and BRCA2. However, the BC risks are predicted to increase with FH-burden. In families with mutations, predicted risks for mutation-negative members depend on both FH and the specific mutation. The reduction in BC risk after negative predictive-testing is greatest when a BRCA1 mutation is identified in the family, but for women whose relatives carry a CHEK2 or ATM mutation, the risks decrease slightly.

Conclusions

The model may be a valuable tool for counselling women who have undergone gene-panel testing for providing consistent risks and harmonizing their clinical management. A web-application can be used to obtain BC- risks in clinical practice (http://ccge.medschl.cam.ac.uk/boadicea/).

Keywords: breast cancer, risk prediction, BOADICEA, BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, CHEK2, ATM, user interface, gene-panel

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer exhibits strong familial aggregation, such that the risk of the disease increases with increasing number of affected relatives. First degree relatives of women diagnosed with breast cancer are at approximately 2 times greater risk of developing breast cancer themselves than women from the general population1. Many breast cancer susceptibility variants have been identified to date. Approximately 15-20% of this excess familial risk is explained by rare, high penetrance mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA22,3. Other rare, intermediate risk variants (e.g. PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM) are estimated to account for ~5% of the breast cancer familial aggregation4-6, and the common, low-risk alleles to account for a further 14% of familial risk7,8.

To provide comprehensive genetic counselling for breast cancer, it is important to have risk prediction models that take into account the effects of all the known susceptibility variants, and also account for the residual familial aggregation. Some existing genetic risk prediction algorithms incorporate the effects of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, including BRCAPRO9, IBIS10 and BOADICEA3,11. BOADICEA accounts for the residual familial aggregation of breast cancer in terms of a polygenic component that models the multiplicative effects of a large number of variants each making a small contribution to the familial risk3.

Next generation sequencing technologies that enable the simultaneous sequencing of multiple genes through gene-panels12,13 have now entered clinical practice. However, the clinical utility of results from such genetic testing remains limited as none of the currently available risk prediction models incorporate the simultaneous effects of rare-intermediate risk variants and other risk factors, in particular explicit family history. As a result, providing risk estimates for women who carry these mutations, and their relatives, is problematic6.

In this paper, we describe an extension to the BOADICEA model to incorporate the effects of intermediate risk variants for breast cancer, specifically loss of function mutations in the three genes for which the evidence for association is clearest and the risk estimates most precise: PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM. The resulting model allows for consistent breast cancer risk prediction in unaffected women on the basis of their genetic testing and their family history.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Breast Cancer Incidence in BOADICEA

We build on the existing BOADICEA model2,3,11. Briefly, in this model, the breast cancer incidence, λi(t), for individual i at age t is assumed to be birth cohort specific, and to depend on the underlying BRCA1 and BRCA2 genotypes and the polygenotype through a model of the form:

| Equation(1) |

where λ0 is the baseline incidence for the cohort, G1i is an indicator variable taking values 1 if a BRCA1 mutation is present and 0 otherwise, and similarly G2i for BRCA2. β1(t) and β2(t) represent the age-specific log-relative risks associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations respectively, relative to the baseline incidence (applicable to a non-mutation carrier with a zero polygenic component) and where Pi(t) is the polygenic effect, assumed to be normally distributed with mean 0 and variance .

The effects of mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are modelled through a single locus “major gene” with three alleles (BRCA1, BRCA2 and wild-type). The BRCA1 and BRCA2 alleles are assumed to be dominantly inherited14. As a further simplification, carriers of both the BRCA1 and BRCA2 alleles are assumed to be susceptible to BRCA1 risks. These simplifications reduce the number of possible “major” genotypes from 9 to 3: a BRCA1 mutation carrier; a BRCA2 mutation carrier; and a non-mutation carrier.

The BOADICEA genetic model uses the Elston-Stewart peeling algorithm to compute the pedigree likelihood15,16. As a result, the number of computations increases exponentially with the number of possible genotypes. To maintain computational efficiency, we incorporated the effects of risk-conferring variants in PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM into the model by introducing an additional allele for each gene (representing a mutation in that gene) to the major gene locus, resulting in a locus with 6 alleles. In comparison with a model that has a single locus for each gene, this approximation is justified by the low allele mutation frequencies for all genes (Table 1), because the probability of carrying more than one mutation is low17, relative to the probability of carrying one or no mutation. Currently, few published data describe the cancer risks for carrying more than one mutation18. Here we assumed that the risks follow a dominant model, with the order of precedence BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, CHEK2, ATM and wild-type. Under this model, in the presence of a mutation in one gene, no additional risk is conferred by a second mutation in another gene lower in the dominance chain.

Table 1.

Mutation frequency and relative risks (RR) for loss of function variants in PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM. The RRs for PALB2 are taken from20. The mutation frequency for PALB2 is taken from a private communication from Easton and Pharaoh based on data from unaffected individuals from the UK. Relative risks for CHEK2 and ATM are taken from6. The allele frequency for CHEK2 is taken from28, and the allele frequency for ATM is taken from29.

| PALB2 | CHEK2 | ATM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allele Frequency | 0.057 % | 0.26% | 0.19 % |

| Age | Relative Risk (95%CI) | ||

| 20-24 | 9.01 (5.70-14.16) | 3.0(2.6-3.5) | 2.8 (2.2-3.7) |

| 25-29 | 8.97 (5.68-14.08) | ||

| 30-34 | 8.85 (5.63-13.78) | ||

| 35-39 | 8.54 (5.51-13.08) | ||

| 40-44 | 8.03 (5.29-11.95) | ||

| s45-49 | 7.31 (4.98-10.55) | ||

| 50-54 | 6.55 (4.60-9.18) | ||

| 55-59 | 5.92 (4.27-8.10) | ||

| 60-64 | 5.45 (4.00-7.33) | ||

| 65-69 | 5.10 (3.80-6.76) | ||

| 70-74 | 4.82 (3.63-6.33) | ||

| 75-79 | 4.56 (3.48-5.95) | ||

Relative Risks for Female Breast Cancer

We extended the model for the breast cancer incidence to incorporate the effects of variants in PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM, such that:

| Equation(2) |

where λ0 , β1(t), G1i, β2(t) and G2i are as described in Equation(1), and G3i , G4i , and G5i , are indicator variables taking values 1 if a mutation is present and 0 otherwise, for PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM respectively. β3(t), β4(t) and β5(t) represent the age-specific log-relative risks associated with PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM mutations respectively, relative to the baseline incidence (applicable to a non-mutation carrier with a zero polygenic component). PRi(t) is the residual polygenic component, with mean 0, and variance , explained below.

To implement the model, we assumed the mutation frequencies and relative risks (RRs) summarised in Table 1. The RR estimates are relative to the population incidences and are therefore over all polygenic effects. Multiplying these RRs by the cohort and age specific incidences yields the average incidences in carriers of PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM mutations over all polygenic effects. To obtain β3(t), β4(t) and β5(t), we constrained the overall incidences (using as weights the major genotype and polygenic frequencies) to agree with the population breast cancer incidence, for each birth cohort separately. This process is detailed elsewhere14.

To ensure that the familial risks predicted by this extended model remain consistent with the previous model, we adjusted the variance of the polygenic component to account for the fact that the contributions of PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM to the genetic variance are now explicitly accounted for in the major gene, following the process described in19. Briefly, the total polygenic variance () was decomposed into the sum of the known variance (), due to the three variants, and residual variance (),

The known variance, , can be calculated from the RRs and mutation frequencies of the variants19. This assumes the effects of each variant and the residual polygene are multiplicative, which agrees with recent findings for PALB2 20. This model is also consistent with the higher RR for CHEK2 1100delC for breast cancer based on familial cases21,22, the higher RR for bilateral breast cancer23, and the increased risk in relatives of breast cancer patients who are CHEK2 carriers24. A higher RR for familial breast cancer for ATM carriers has also been found, though data are more limited25.

PALB2 Characteristics

Due to limited case-control studies for PALB2 or ATM, we used alternative family-based data. Age dependent RRs of female breast cancer for carriers of loss of function variants in PALB2 were taken from a large collaborative family-based study20. With the exception of specific Nordic founder mutations, data on mutation frequencies in the general population are sparse. We assumed a mutation allele frequency of 0.057% based on data from targeted sequencing of from 8705 UK controls (unpublished data). This is close to the average estimate across published estimates26.

CHEK2 Characteristics

Most existing data describe the CHEK2 1100delC variant, which is the most common truncating variant in northern European populations27. CHEK2 1100delC has been evaluated in many case-control studies22,28. As a result, we based the CHEK2 estimates on the CHEK2 1100delC carrier estimates from a meta-analysis28. We assumed that the allele frequency of the 1100delC mutations was 0.26%, the combined frequency across unselected population controls of European ancestry28. There is some evidence that the RRs for breast cancer in CHEK2 1100delC carriers decline with age22. However, since age-specific estimates are currently imprecise, we used a single RR across all ages.

ATM Characteristics

We obtained estimates for truncating mutations in ATM from a combined analysis of three estimates from cohort studies of relatives of Ataxia-Telangiectasia (A-T) patients (Table 1)6. The large majority of A-T patients carry two truncating ATM mutations, and relatives of A-T patients are therefore known to have a high probability of being carriers of an ATM mutation. We assumed that the allele frequency of truncating variants in ATM was 0.19%, based on data from UK controls25. As for CHEK2, there is some evidence of a decline in RR with age29, but without precise estimates, we used a single estimate across all ages.

Relative Risks for Other Cancers

In addition to the risks of female breast cancer, BOADICEA takes into account the associations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with the risks of male breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers3. Several studies have investigated associations of the truncating variants in PALB2, ATM and CHEK2 1100delC with the risks of these cancers (and others)20,29-31. However, none of the studies provided convincing evidence of association for any of these cancers, and accurate penetrance estimates are currently lacking for those cancers that may have associations. Therefore, for the purpose of the current implementation, we assumed that these mutations are not associated with risks of other cancers.

Incorporating Breast Tumour Pathology Characteristics

Previous studies2,11 describe the incorporation into BOADICEA of differences in tumour pathology subtypes between BRCA1, BRCA2 and non-carrier breast cancers. Specifically, BOADICEA includes information on tumour oestrogen receptor (ER) status, triple negative (oestrogen, progesterone and HER2 negative) (TN) status, and the expression of basal cytokeratin markers CK5/6 and CK14.

Breast cancers in CHEK2 1100delC mutation carriers have been found to be ER-positive, at a greater proportion compared to tumours in non-CHEK2 mutation carriers (88% vs 78% in general population)32. Reliable data pertaining to the TN and basal cytokeratin receptor status are not currently available. Therefore, in the current implementation, we only incorporated differences by breast cancer ER-status for CHEK2 1100delC carriers. Age specific distributions were not available.

Published data on the prevalence of tumour subtypes in PALB2 associated breast cancers are sparse, and although some differences compared to the general population have been reported, these are based on small numbers20,33. Currently there are no available data pertaining to tumour pathology subtype distributions for carriers of ATM truncating mutations. We therefore assumed that tumour subtype distributions for PALB2 and ATM mutation carriers are the same as the general population.

Mutation Screening Sensitivity

We have introduced separate mutation test screening sensitivities for PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM to allow for the fact that some risk-conferring variants in these genes may be missed by current methods. In the BOADICEA Web Application (BWA), we assumed default values of 90% for PALB2 and ATM truncating variants, and 100% for the CHEK2 1100delC variant. However, these values can be customised by users. The specificity of mutation testing was assumed to be 100%.

RESULTS

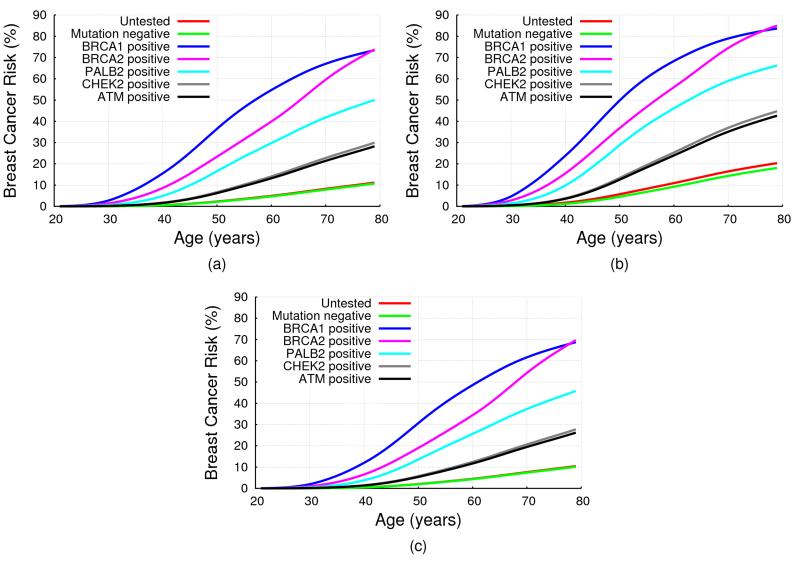

Fig 1(a) shows the implied average cumulative breast cancer risks predicted by BOADICEA by mutation status, on the basis of the assumed RRs for an unaffected female aged 20. The predicted average breast risk by age 80 for for an ATM mutation carrier was 28.2%, 29.9% for CHEK2, 50.1% for PALB2, 73.5% for BRCA1 and 73.8% for BRCA2.

Figure 1. BOADICEA Breast Cancer Risk by Mutation Status and Family History.

BOADICEA risk by mutation status for a female in the UK age 20 born in 1975: (a) with unknown family history (i.e. for the average female in the population); (b) with her mother affected at age 40; (c) with her mother and sister unaffected at ages 70 and 50 respectively. No testing assumed in other family members, in all cases.

On the basis of the assumed mutation frequencies and RRs and modelling assumptions, the known polygenic variance () due to the effects of PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM are given in Table 2. The age dependence of the variances due to PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM is a consequence of the fact that relative risks vary with age (in particular for PALB2) and the age dependence of the frequency of mutation carriers among the unaffected population, which decreases with age (elimination effect). The proportion of polygenic variance accounted for by these genes varied from 3.0% at age 25 to 9.8% at age 75.

Table 2.

The variance explained by PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM and the percentage of the overall polygenic variance explained by all three combined.

| Age | PALB2 Variance | CHEK2 Variance | ATM Variance | % of total Polygenic Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0.0691 | 0.0201 | 0.0121 | 3.04 |

| 30 | 0.0668 | 0.0201 | 0.0121 | 3.26 |

| 35 | 0.0611 | 0.0201 | 0.0121 | 3.40 |

| 40 | 0.0519 | 0.0199 | 0.012 | 3.43 |

| 45 | 0.0403 | 0.0197 | 0.0119 | 3.35 |

| 50 | 0.0294 | 0.0193 | 0.0116 | 3.26 |

| 55 | 0.0216 | 0.0188 | 0.0114 | 3.34 |

| 60 | 0.0165 | 0.0182 | 0.0111 | 3.66 |

| 65 | 0.013 | 0.0176 | 0.0108 | 4.34 |

| 70 | 0.0105 | 0.017 | 0.0104 | 5.77 |

| 75 | 0.0085 | 0.0164 | 0.0101 | 9.77 |

Mutation Carrier Probabilities

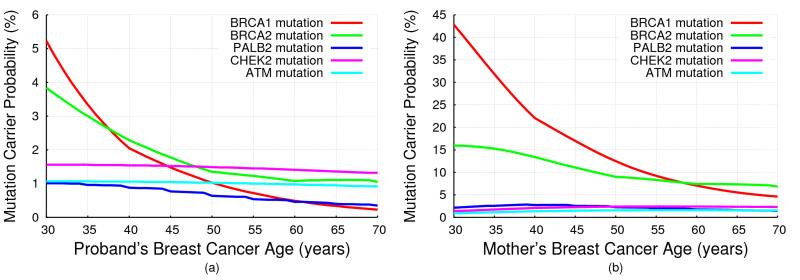

Fig 2 shows the mutation carrier probabilities predicted by BOADICEA, for (a) a female with unknown family history as a function of her age of cancer diagnosis, and (b) for a 30 year old female diagnosed with breast cancer, whose mother has had breast cancer, as a function of her mother’s age at diagnosis (also given in Tables S1 and S2). The mutation carrier probabilities for ATM and CHEK2 did not show a marked change with age at diagnosis (reflecting the assumption of a constant RR), but the mutation carrier probabilities for PALB2 decreased with age, though less markedly than for BRCA1/2. The mutation carrier probabilities were higher for women with a family history, but the effect was more marked for BRCA1/2 and PALB2 than for CHEK2 or ATM.

Figure 2. BOADICEA Mutation Carrier Probabilities.

BOADICEA mutation carrier probabilities for a female in the UK, born in 1975: (a) with unknown family history as a function of her breast cancer diagnosis age; (b) who was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 30 and whose mother was diagnosed with breast cancer, as a function of her mother’s age at diagnosis.

Predicted Cancer Risks for Mutation Carriers are Family History Specific

In our model, the residual polygenic component was assumed to act multiplicatively with PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM mutations on breast cancer risk. As a result, the risks for mutation carriers will vary by family history. Fig 1 shows the predicted cumulative breast cancer risk for a 20 year old woman by her mutation status. In (a) the woman was assumed to have unknown family history; in (b) to have a mother affected with breast cancer at age 40; and in (c) to have a mother and sister who are cancer free at ages 70 and 50 respectively. These show clearly that predicted breast cancer risks increased with increasing number of affected relatives, and depend on the phenotypes of unaffected family members. For example, although the average breast cancer risks by age 80 for CHEK2 and ATM mutation carriers were lower than 30% (a common criterion for “high” risk, for example the NICE guideline34) the breast cancer risk exceeded this threshold when a mutation carrier had a family history of breast cancer (e.g. 42.6% for ATM and 44.7% for CHEK2,with an affected mother). Comparing Figures 1 (c) and 1 (a) we see that the risk for a woman with no history of breast cancer is lower than the average breast cancer risk.

The Effect of Negative Predictive Testing

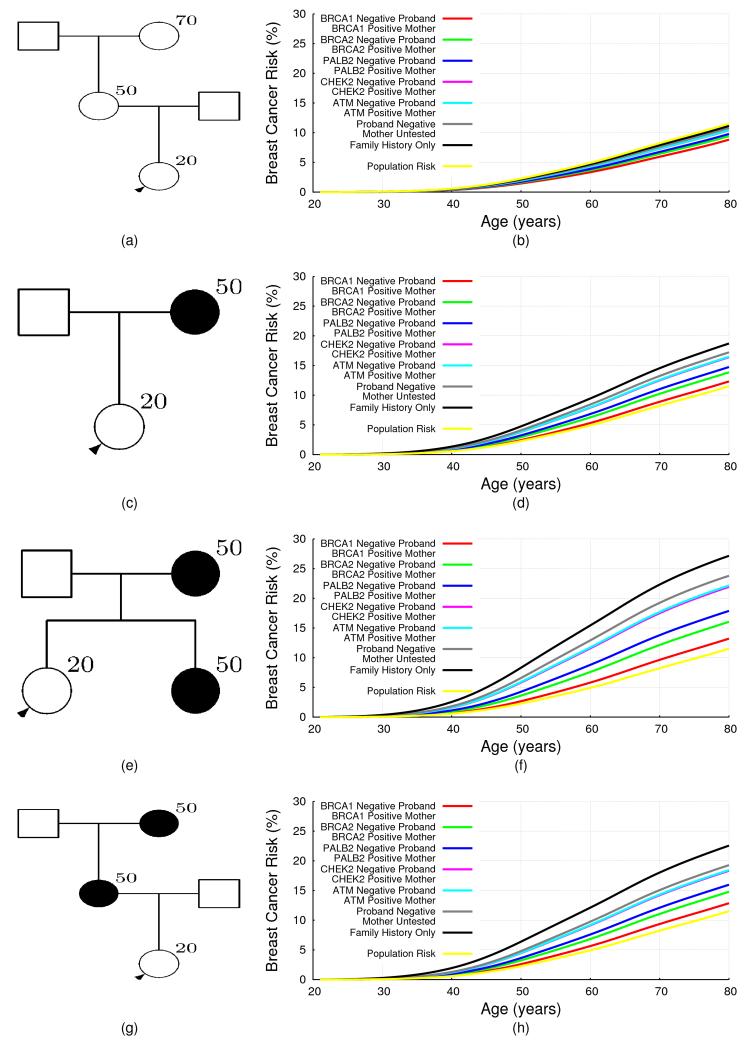

The extended BOADICEA model can also be used to predict risks in families in which mutations are identified, but other family members test negative. This is demonstrated for a number of family history scenarios in Fig 3, which depend on the mutation status of the proband and her mother. The predicted risks for mutation negative family members depend on both the family history and the specific mutation identified. Thus for families with a history of breast cancer, namely (c), (e) and (g), the reduction in breast cancer risk after negative predictive testing is greatest when a BRCA1 mutation was identified in the family, with the risks being close to (though still somewhat greater than) population risk. This effect was most noticeable for women with a strong family history. The reduction for women whose mother carried a BRCA2 or PALB2 mutation is less marked, while for women whose mother carried a CHEK2 or an ATM mutation, the risks decreased only slightly with a negative predictive test, even with a strong family history. For a woman with no history of (Figure 3 (a)), her risk on the basis of family history alone (i.e. in an untested family) was slightly lower than the population risk. After negative predictive testing her predicted risk decreased further. The biggest decrease was observed when a BRCA1 mutation was identified in the mother.

Figure 3. BOADICEA Breast Cancer Risk for Negative Testing by Family History.

The predicted risk of breast cancer for a 20 year old female in the UK, born in 1975 by her mother’s mutation status, for different family histories. The predicted risk is shown for four different family histories. The graphs on the right hand side correspond to the pedigrees on the left hand side. The figures show the predicted risks for a proband (shown with an arrow) in families without any mutation testing in the five genes i.e. this corresponds to the predicted risk on the basis of family history information alone (black curves). The rest of the curves correspond to the cases where the proband is assumed to be negative for the mutation identified in the family. To enable direct comparisons, the proband is assumed to be 20 years old in all examples.

Updates to the BOADICEA Web Application

We have now updated the BWA (http://ccge.medschl.cam.ac.uk/boadicea/) to accommodate these extensions to the BOADICEA model. The BWA enables users to either build a pedigree online, or to upload pedigrees. When users build an input pedigree online, the program now enables users to specify PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM genetic test results. Similarly, we have extended the BOADICEA import/export format (described in Appendix A of the BWA v4 user guide: https://pluto.srl.cam.ac.uk/bd4/v4/docs/BWA_v4_user_guide.pdf) so that users can include this information in their files.

DISCUSSION

Cost-effective sequencing technologies have brought multi-gene panel testing into mainstream clinical care6,13,35. Although several established breast cancer susceptibility genes are included in these panels, their clinical utility is limited by the lack of risk prediction models that consider the effects of mutations in these genes and other risk factors, in particular family history. Here, we present an extended BOADICEA model that incorporates the effects of rare protein truncating variants in PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM. This is the first breast cancer risk model to include the explicit effects of susceptibility genes other than BRCA1 and BRCA2, and it can be used to provide comprehensive risk counselling on the basis of family history and mutation screening in the five genes. The model can also be used to predict risks of developing breast cancer and the likelihood of carrying truncating mutations in any of the five genes.

The extended BOADICEA model is based on a number of assumptions. To ensure the model is computationally efficient we used a single “major” locus with six alleles representing the truncating variants in the five genes and a wild-type allele. In comparison with a model consisting of 5 separate loci each with 2 alleles, this should be a reasonable approximation as all the variants are rare. However, it is possible that the effects will be greater in families segregating more than one rare variant. It also represents a substantial reduction in the number of genotypes (36 V’s 1024), and hence in execution time; we measure execution time to be reduced by a factor of 21000. These simplifications will become more critical as the number of susceptibility genes included in the model increases. A previous study6 identified six other genes for which the association with breast cancer was well established (TP53, PTEN, STK11, CDH1, NF1 and NBN), and this list is likely to increase with time.

Without robust data on risks to carriers of 2 or more truncating variants (in different genes), we assumed that dual mutation carriers develop breast cancer according to incidences for the higher penetrance gene. Recent evidence suggests that gene-gene interaction between CHEK2, ATM, BRCA1 and BRCA2 may not be multiplicative (indeed a multiplicative model would be implausible for BRCA1 and BRCA2, since it would predict an extremely high risk at very young ages)18. This may reflect the biological relationships between the proteins encoded by the genes. The proteins encoded by all five genes play roles in DNA repair, and loss of function mutations in these genes are predicted to impair DNA repair. Our implementation would be consistent with a model where if the pathway is disrupted by one mutation, further disruption by a lower penetrance mutation would not increase risk.

Although there is strong evidence that mutations in PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM confer increased risk of breast cancer in females6, there are currently no precise risk estimates for the other cancers considered by BOADICEA (male breast, ovarian, pancreatic or prostate), or indeed other cancers. However, several studies have provided tentative evidence of associations20,31. Due to the lack of precise cancer risk estimates, we have assumed no association between truncating variants in PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM (i.e. RR=1). If there are true associations between the PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM truncating variants and other cancer risks, we expect that PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM mutation carrier probabilities may potentially be underestimated in families where other cancers occur. However, should accurate risk become available, they can easily be included in our implementation.

BOADICEA allows cancer tumour characteristics to be taken into account, as we have done previously for BRCA1 and BRCA22,11,36. The provision of subtype-specific risks can be useful for genetic counselling and may guide chemoprevention. However, data on the additional genes are currently sparse. In this model, we incorporated a higher probability of ER-positive tumours in CHEK2 1100delC carriers, relative to non-carriers32. Some studies have suggested differences in the tumour characteristics from PALB2 mutation carriers and non-carriers, but larger studies are required to establish such differences20,33.

We considered only the effects of truncating variants in PALB2, ATM and of the CHEK2 1100delC variant, for which robust breast cancer risk estimates are available. In doing this, we are making the usual simplification that all truncating variants in these genes confer similar risks. While there is no evidence to contradict this, it may change as further data accumulate. Also, there is evidence that missense variants in CHEK2 and ATM confer elevated breast cancer risks, but that the risks that they confer can differ from the risks associated with truncating variants. For example, the ATM c.7271T>G missense variant has been reported to confer a higher risk than truncating variants, but the confidence intervals associated with this estimate are currently wide37. It has been suggested that other rare, evolutionarily unlikely missense variants in ATM are also associated with increased breast cancer risks38. Future extensions of BOADICEA can accommodate such differences on the basis of more precise cancer risk estimates. In CHEK2, the missense variant Ile157Thr has been associated with a lower risk than the 1100delC variant39. This variant has been incorporated into a polygenic risk score on the basis of common genetic variants40 , which we expect to incorporate into BOADICEA in the future.. The model could also be applicable for other truncating variants in CHEK2 , under the assumption that they confer similar risks to the 1100delC variant. However, the available data are scarce and some modification of the mutation frequencies may be required.

Under the BOADICEA model, women testing negative for known familial mutations (true negatives) and who have family history are predicted to be at higher risk of breast cancer than the general population. The level of risk depends on both family history and the specific mutation identified. So far, epidemiological studies have reported estimates for “true negatives” only for families with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations41-46 but the estimated relative risks (compared to the population risks) vary widely. Moreover, all the reported estimates are associated with wide confidence intervals because the studies have been based on small sample sizes. The reported estimates are summarised in Table S3. To provide a direct comparison with the predicted risks by BOADICEA we have included the implied relative risks for the “true negative” women in Figure 3 relative to the population. These are all in line with the published estimates for true negatives. Therefore, the predictions by BOADICEA are consistent with published data. It is worth noting that if the true relative risks for the “true negatives” in families with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are in line with those predicted by BOADICEA, very large prospective studies of “true negatives” would be necessary to demonstrate significant associations.

The current model is a synthetic model, based on segregation analyses of families in the UK together with risk estimates derived from studies of European populations. We have previously implemented procedures for extrapolating the model to populations with different baseline incidence rates, on the assumption that the RRs conferred by the genetic variants in the model are independent of the population11. Thus, the model should be broadly applicable to developed populations of European ancestry, but its applicability to populations with lower incidence rates, and populations of non-European ancestry, has yet to be evaluated. The implementation also allows the allele frequencies to be adjusted. This may be particularly relevant for CHEK2; in European populations the founder 1100delC variant accounts for the majority of carriers of truncating variants, and its frequency varies across populations.

The extended BOADICEA model presented here has addressed a major gap in breast cancer risk prediction, by including the effects of truncating variants in PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM that are included in widely used commercial gene-panels. The model could be a valuable tool in the counselling process of women who have undergone gene-panel testing for providing consistent breast cancer risks and thus harmonizing the clinical management of at risk individuals. Future studies should aim to validate this model in large prospective cohorts with mutation screening information and to evaluate the impact of the risk predictions on decision making.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by Cancer Research UK Grants C12292/A11174 and C1287/A10118. ACA is a Cancer Research UK Senior Cancer Research Fellow. This work was supported by the Governement of Canada through Genome Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the Ministère de l'enseignement supérieur, de la recherche, de la science et de la technologie du Québec through Génome Québec.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no known conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast C Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet. 2001 Oct 27;358(9291):1389–1399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06524-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mavaddat N, Rebbeck TR, Lakhani SR, Easton DF, Antoniou AC. Incorporating tumour pathology information into breast cancer risk prediction algorithms. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(3):R28. doi: 10.1186/bcr2576. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoniou AC, Cunningham AP, Peto J, et al. The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancers: updates and extensions. Br J Cancer. 2008 Apr 22;98(8):1457–1466. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604305. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apostolou P, Fostira F. Hereditary breast cancer: the era of new susceptibility genes. BioMed research international. 2013;2013:747318. doi: 10.1155/2013/747318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson D, Easton D. The genetic epidemiology of breast cancer genes. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia. 2004 Jul;9(3):221–236. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMG.0000048770.90334.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Easton DF, Pharoah PD, Antoniou AC, et al. Gene-panel sequencing and the prediction of breast-cancer risk. N Engl J Med. 2015 Jun 4;372(23):2243–2257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1501341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michailidou K, Hall P, Gonzalez-Neira A, et al. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2013 Apr;45(4):353–361. 361e351–352. doi: 10.1038/ng.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michailidou K, Beesley J, Lindstrom S, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of more than 120,000 individuals identifies 15 new susceptibility loci for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2015 Apr;47(4):373–380. doi: 10.1038/ng.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parmigiani G, Berry D, Aguilar O. Determining carrier probabilities for breast cancer-susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(1):145–158. doi: 10.1086/301670. 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyrer J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J. A breast cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Statistics in medicine. 2004 Apr 15;23(7):1111–1130. doi: 10.1002/sim.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee AJ, Cunningham AP, Kuchenbaecker KB, et al. BOADICEA breast cancer risk prediction model: updates to cancer incidences, tumour pathology and web interface. British journal of cancer. 2014 Jan 21;110(2):535–545. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robson M. Multigene panel testing: planning the next generation of research studies in clinical cancer genetics. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Jul 1;32(19):1987–1989. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurian AW, Hare EE, Mills MA, et al. Clinical evaluation of a multiple-gene sequencing panel for hereditary cancer risk assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Jul 1;32(19):2001–2009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoniou AC, Pharoah PD, McMullan G, Day NE, Ponder BA, Easton D. Evidence for further breast cancer susceptibility genes in addition to BRCA1 and BRCA2 in a population-based study. Genet Epidemiol. 2001;21(1):1–18. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1014. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lange K, Weeks D, Boehnke M. Programs for Pedigree Analysis: MENDEL, FISHER, and dGENE. Genet Epidemiol. 1988;5(6):471–472. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370050611. 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lange K. Mathematical and statistical methods for genetic analysis. Springer; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tung N, Battelli C, Allen B, et al. Frequency of mutations in individuals with breast cancer referred for BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing using next-generation sequencing with a 25-gene panel. Cancer. 2015 Jan 1;121(1):25–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turnbull C, Seal S, Renwick A, et al. Gene-gene interactions in breast cancer susceptibility. Hum Mol Genet. 2012 Feb 15;21(4):958–962. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macinnis RJ, Antoniou AC, Eeles RA, et al. A risk prediction algorithm based on family history and common genetic variants: application to prostate cancer with potential clinical impact. Genet Epidemiol. 2011;35(6):549–556. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20605. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antoniou AC, Casadei S, Heikkinen T, et al. Breast-cancer risk in families with mutations in PALB2. N Engl J Med. 2014 Aug 7;371(6):497–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meijers-Heijboer H, van den Ouweland A, Klijn J, et al. Low-penetrance susceptibility to breast cancer due to CHEK2(*)1100delC in noncarriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Nat Genet. 2002 May;31(1):55–59. doi: 10.1038/ng879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Consortium CBCC-C CHEK2*1100delC and susceptibility to breast cancer: a collaborative analysis involving 10,860 breast cancer cases and 9,065 controls from 10 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Jun;74(6):1175–1182. doi: 10.1086/421251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fletcher O, Johnson N, Dos Santos Silva I, et al. Family history, genetic testing, and clinical risk prediction: pooled analysis of CHEK2 1100delC in 1,828 bilateral breast cancers and 7,030 controls. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009 Jan;18(1):230–234. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson N, Fletcher O, Naceur-Lombardelli C, dos Santos Silva I, Ashworth A, Peto J. Interaction between CHEK2*1100delC and other low-penetrance breast-cancer susceptibility genes: a familial study. Lancet. 2005 Oct 29 4;Nov 29 4;366(9496):1554–1557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67627-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renwick A, Thompson D, Seal S, et al. ATM mutations that cause ataxia-telangiectasia are breast cancer susceptibility alleles. Nat Genet. 2006 Aug;38(8):873–875. doi: 10.1038/ng1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southey MC, Teo ZL, Winship I. PALB2 and breast cancer: ready for clinical translation! The application of clinical genetics. 2013;6:43–52. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S34116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schutte M, Seal S, Barfoot R, et al. Variants in CHEK2 other than 1100delC do not make a major contribution to breast cancer susceptibility. Am J Hum Genet. 2003 Apr;72(4):1023–1028. doi: 10.1086/373965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Ellervik C, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. CHEK2*1100delC genotyping for clinical assessment of breast cancer risk: meta-analyses of 26,000 patient cases and 27,000 controls. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 1;26(4):542–548. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson D, Duedal S, Kirner J, et al. Cancer risks and mortality in heterozygous ATM mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 Jun 1;97(11):813–822. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji141. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cybulski C, Gorski B, Huzarski T, et al. CHEK2 is a multiorgan cancer susceptibility gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Dec;75(6):1131–1135. doi: 10.1086/426403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helgason H, Rafnar T, Olafsdottir HS, et al. Loss-of-function variants in ATM confer risk of gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2015 Jun 22; doi: 10.1038/ng.3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weischer M, Nordestgaard BG, Pharoah P, et al. CHEK2*1100delC heterozygosity in women with breast cancer associated with early death, breast cancer-specific death, and increased risk of a second breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Dec 10;30(35):4308–4316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.7336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cybulski C, Kluzniak W, Huzarski T, et al. Clinical outcomes in women with breast cancer and a PALB2 mutation: a prospective cohort analysis. The Lancet. 2015 Oncology;16(6):638–644. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Excellence NIfHaC Familial breast cancer: classification and care of people at risk of familial breast cancer and management of breast cancer and related risks in people with a family history of breast cancer (CG164) 2013 http://www.nice.org.uk/CG164. [PubMed]

- 35.Slade I, Riddell D, Turnbull C, Hanson H, Rahman N, programme MCG Development of cancer genetic services in the UK: A national consultation. Genome medicine. 2015;7(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0128-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischer C, Kuchenbacker K, Engel C, et al. Evaluating the performance of the breast cancer genetic risk models BOADICEA, IBIS, BRCAPRO and Claus for predicting BRCA1/2 mutation carrier probabilities: a study based on 7352 families from the German Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Consortium. J Med Genet. 2013;50(6):360–367. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101415. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldgar DE, Healey S, Dowty JG, et al. Rare variants in the ATM gene and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(4):R73. doi: 10.1186/bcr2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tavtigian SV, Oefner PJ, Babikyan D, et al. Rare, evolutionarily unlikely missense substitutions in ATM confer increased risk of breast cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2009 Oct;85(4):427–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kilpivaara O, Vahteristo P, Falck J, et al. CHEK2 variant I157T may be associated with increased breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2004 Sep 10;111(4):543–547. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mavaddat N, Pharoah PD, Michailidou K, et al. Prediction of breast cancer risk based on profiling with common genetic variants. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015 May;107(5) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Domchek SM, Gaudet MM, Stopfer JE, et al. Breast cancer risks in individuals testing negative for a known family mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2010 Jan;119(2):409–414. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0611-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith A, Moran A, Boyd MC, et al. Phenocopies in BRCA1 and BRCA2 families: evidence for modifier genes and implications for screening. J Med Genet. 2007 Jan;44(1):10–15. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.043091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowan E, Poll A, Narod SA. A prospective study of breast cancer risk in relatives of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Med Genet. 2007 Aug;44(8):e89. author reply e88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korde LA, Mueller CM, Loud JT, et al. No evidence of excess breast cancer risk among mutation-negative women from BRCA mutation-positive families. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2011 Jan;125(1):169–173. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0923-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurian AW, Gong GD, John EM, et al. Breast cancer risk for noncarriers of family-specific BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: findings from the Breast Cancer Family Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Dec 1;29(34):4505–4509. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harvey SL, Milne RL, McLachlan SA, et al. Prospective study of breast cancer risk for mutation negative women from BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation positive families. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2011 Dec;130(3):1057–1061. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1733-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.