Abstract

The prospect of changing the plasticity of terminally differentiated cells toward pluripotency has completely altered the outlook of biomedical research. Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) provide a new source of therapeutic cells free from the ethical issues or immune barriers of human embryonic stem cells. iPSCs also confer considerable advantages over conventional methods of studying human diseases. Since its advent, iPSC technology has expanded, with 3 major applications: disease modeling; regenerative therapy; and drug discovery. Here we discuss, in a comprehensive manner, the recent advances in iPSC technology in relation to basic, clinical, and population health.

Keywords: drug discovery, human induced pluripotent stem cells, macromedicine, micromedicine, personalized medicine

Introduction

Since the initial discovery that bone marrow cells possess regenerative capacity through clonal expansion, which laid the foundation for the field (1), regenerative medicine has come a long way. As a type of stem cells, these bone marrow cells have the capacity for both self-renewal and differentiation into different cell types. Earlier attempts to understand the pluripotency of the inner cell mass focused on the developmental capacity of nuclei by cloning in frogs (2), cloning in adult mammalian cells (3), deriving mouse and human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (4,5), and generating ESC and somatic cell fusion (6). Similarly, MyoD, a mammalian transcription factor, was found capable of converting fibroblasts to myocytes, which led to the concept of master regulators, transcription factors that determine lineage specification (7). Using these paradigms, subsequently discovered stem cells were classified as either adult stem cells or ESCs on the basis of their origins and differentiation potentials. The unusual capacities of ESCs to proliferate without senescing (i.e., self-renewal) and to form all cell types of the embryo (i.e., pluripotency) made them unique and valuable resources for studying cell fate and tissue development. Initially, work on pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) was conducted using human ESCs (5); however, the requirement to destroy early-stage embryos in the process of ESC derivation made their use ethically controversial. In addition, practical considerations hindered their medical applications, as any cells or tissues generated from hESCs by definition would be allotransplants into the recipient patient, requiring possible life-long immunosuppression.

The discovery by Shinya Yamanaka et al. that a small set of reprogramming factors (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-myc; OSKM) can induce nuclear reprogramming of mouse (8) and adult human cells (9) to pluripotency became a landmark development in regenerative medicine. Termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), they promised a source of therapeutic cells free from the ethical issues or immune barriers of human ESCs, while retaining similar properties, such as self-renewal and pluripotency. Since that initial discovery, a number of advances have been introduced to enhance both the efficiency of iPSC production and the safety of the resultant lines. These improvements include the use of chemical agents to enhance efficiency (BIX-01294, valproic acid, RG108, AZA, dexamethasone, TSA, and A-83-01) (10,11), use of alternative cell sources for reprogramming (embryonic, fetal, and adult fibroblasts, neural stem cells, adipose stem cells, keratinocytes, and blood cells) (12–14), use of various factors that could replace the reprogramming factors (15,16), use of vectors that can be excised from the genome (17,18), use of “nonintegrating” vectors (19,20), supplementation of reprogramming factors with microribonucleic acids (miRNAs) (21), use of recombinant proteins/peptides to reprogram somatic cells (22,23), and, most recently, a purely chemical approach (24).

With the concerted efforts of the academic community, the last decade has seen a tremendous push toward the efficient generation of safer pluripotent stem cells, with the hope that one day iPSCs could be used for regenerative medicine in the clinic (25). Although halted temporarily, the clinical trial using iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelial (iPSC-RPE) cells for treatment of macular degeneration shows how far we have come in developing clinical-grade stem cells (26). In the short run, iPSC technology will likely offer more avenues to understand the pathophysiology of diseases and discover new therapeutic molecules. Specifically, for disease modeling, iPSCs can be generated from patients carrying certain genetic mutations and then differentiated into disease-relevant cell types, such as cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) (27–29). Similarly, iPSC-derived cells can then be subjected to high-throughput screens to discover new therapeutic small molecules or conduct drug toxicity assays. Lastly, iPSC technology may enable personalized therapies (i.e., cell or tissue replacement without the need for immunosuppression, and use of drugs tailored according to each patient's genes, environment, and lifestyle). This is precision medicine, an initiative with the intent to cure each patient by taking into account his or her unique genetic makeup (30). The goal is to understand the complex mechanism of diseases so that made-to-order treatment plans could be designed for each patient on the basis of their condition. In this review paper, we aim to highlight the promise of iPSCs for expanding basic science research and generating novel therapeutics for clinical and public health applications.

iPSC TECHNOLOGY: EMERGING CONCEPTS

The greatest hallmark of iPSC technology lies in its simplicity and reproducibility. Although the past decade has shown great improvement in making iPSCs safer and more efficacious, which is critical for pushing the technology towards clinical application, the mechanisms involved in efficient generation of iPSCs are just emerging. These evolving concepts raise important fundamental questions that will be discussed in the following sections.

How can a few transcription factors turn back the cellular clock?

Many studies have tried to address this question, but the general consensus is that the initial activity of the core pluripotency genes (OSKM) has a “snowball effect” that results in simultaneous activation of the entire endogenous network of pluripotency genes and inhibition of lineage-specific genes within the reprogrammed somatic cells. The initial phase of reprogramming is associated with cells undergoing metabolic changes, and genome-wide alterations in histone marks and methylation, followed by a late maturation phase that causes defined changes in nuclear structure, the cytoskeleton, and signaling pathways (31,32). Indeed, by looking closely at these mechanisms, researchers can now obtain nearly perfect iPSCs by clearing previous roadblocks to reprogramming (33).

Are these iPSCs the same as ESCs?

An important question that comes up repeatedly is whether iPSCs have the same genetic and epigenetic landscape as ESCs, and whether differentiated cells (e.g., cardiomyocytes [CMs]) from these 2 types of stem cells behave similarly. Despite several earlier studies suggesting differences in gene expression or deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) methylation between iPSCs and ESCs (34–36), the majority of iPSC and ESC clones are largely indistinguishable (37–39). More recent reports suggest that both cell types have identical molecular and functional characteristics, with variations in their genetic backgrounds (i.e., different donors for iPSCs and ESCs) accounting for most of their regulatory differences (40).

Could transdifferentiation be the next step?

Another emerging concept is the direct reprogramming of one somatic cell type to another desired cell type as an alternative approach to iPSCs. Termed transdifferentiation, this concept relies on the premise that we could achieve rapid reprogramming of a desired cell type by entirely avoiding the iPSC stage (41). Several groups have shown successful transdifferentiation of fibroblasts to various types of somatic cells, such as neurons (42), hepatocytes (43), CMs (44), and endothelial cells (45,46). However, a current major drawback to the use of direct reprogramming for clinical purposes is the tremendous difficulty of obtaining sufficient numbers of target cells that fully recapitulate the properties of the desired cells (47). In addition, transdifferentiation has thus far failed to generate a pure population of desired cells, making it difficult for them to be used for disease modeling and drug development (48). Similarly, in contrast to iPSCs, which once reprogrammed can be easily maintained and differentiated to a desired cell type, the transdifferentiation approach would require restarting the entire reprogramming process for each experiment.

APPLICATIONS OF iPSCs

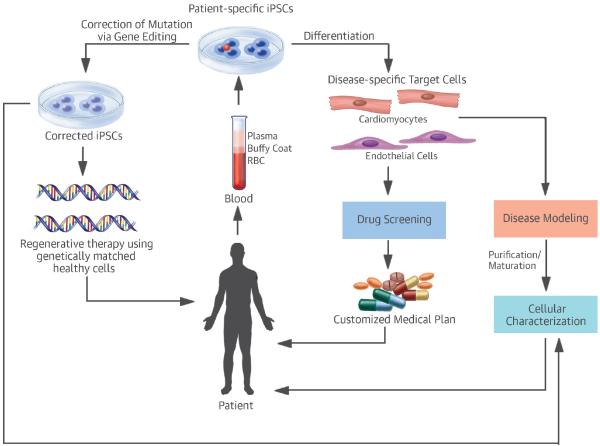

There are many human diseases that have limited treatment options, due to either lack of relevant tissue samples or lack of information regarding disease progression. Thus, researchers traditionally have relied on in vitro assays or animal models to understand disease progression and develop therapeutic interventions. These model systems use either small animals (e.g., rats and mice) or large animals (e.g., dogs, pigs, and nonhuman primates). These research designs are premised on the animal model's ability to mimic human subjects pathophysiologically and to eventually develop end-stage disease like that seen in humans. However, due to differences in cardiovascular anatomy and physiology (e.g., humans and rodents diverged ~75 million years ago), animal models often do not accurately reproduce human pathophysiology in meaningful ways. Because iPSCs can be derived from healthy and diseased patients, they can be a robust alternative to animals for modeling human diseases (Figure 1). Indeed, several models of iPSCs have been generated and explored for studying various human diseases, as outlined in the next section.

Figure 1. Potential Applications of Patient-Specific iPSCs.

Disease-specific target cells differentiated from patient-specific iPSCs have 3 major applications: disease modeling; regenerative therapies; and drug discovery/toxicity studies. iPSCs from patients with genetic mutations could be corrected via genome editing to yield healthy target cells for cell therapy. Both corrected and uncorrected target cells could be used for disease modeling or drug screening. iPSC = induced pluripotent stem cell; RBC = red blood cells.

Disease modeling

The inherent properties of iPSCs for self-renewal and differentiation into any cell type make them an ideal candidate for modeling human diseases. Because many of the genetic variants that distinguish affected patients from unaffected subjects are located in noncoding regions of the human genome with limited alignment to genomes of animals used as model systems, we run the risk that even after introducing the same human genetic variant in the animal model, we might fail to recapitulate the human disease phenotype (49). Thus, there is a compelling need to model human diseases using human samples. Since the groundbreaking creation of the first human iPSCs (9), many groups have applied this technology to model human diseases, with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and various congenital diseases among the first to be modeled using patient-specific iPSCs (12,50,51). Following these reports, many have attempted to study human diseases using iPSCs from patients suffering from neurodegenerative diseases (50,52), cardiovascular disorders (53–56), muscular dystrophies (57,58), and hematologic disorders (59,60), to name a few. Cardiovascular diseases that have been studied are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of Cardiac Diseases Modeled Using iPSCs.

| Category | Disease | Locus | Features | Gene Correction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Cardiac | CPVT | CASQ2 | - Arrhythmia and abnormal Ca2+ signaling | No | (147) |

| RYR2 | - Arrhythmia and abnormal Ca2+ signaling | No | (147) | ||

|

| |||||

| HCM | MYH7 | - Abnormal calcium handling, disorganized sarcomeres, and electrophysiological irregularities | No | (71) | |

|

| |||||

| DCM | LMNA | - Nuclear senescence and cellular apoptosis | No | (148) | |

| TNNT2 | - Altered regulation of Ca2+, decreased contractility, and abnormal distribution of sarcomeric α-actinin | No | (72,73) | ||

| TTNtv | - Sarcomere abnormalities, impaired contractility and response to stress | No | (74) | ||

| DES | - Abnormal desmin aggregations, aberrant calcium handling, and beating rate | No | (149) | ||

| PLN | - Abnormal calcium handling, electrical instabilities, and increased cardiac hypertrophy markers | Yes | (97) | ||

| MYBPC3 | - Contraction defects | No | (150) | ||

|

| |||||

| BTHS | TAZ | - Sarcomere assembly and myocardial contraction abnormalities | No | (98) | |

|

| |||||

| LQT1 | KCNQ1 | - Prolonged duration of AP, aberrant electrophysiological K+ current, and protective action of beta-blockade | No | (64) | |

|

| |||||

| LQT2 | KCNH2 | - Prolongation of the AP duration, reduction of the cardiac potassium current I (Kr), and arrhythmogenicity | Yes | (54,55,64) | |

|

| |||||

| LQT3 | SCN5A | - Prolonged AP duration and persistent Na+ current | No | (151) | |

|

| |||||

| LQT8 | CACNA1C | - Defects in Ca2+ signaling and arrhythmia | No | (66) | |

|

| |||||

| ARVD | PKP2 | - Exaggerated lipogenesis, desmosomal distortion | No | (69) | |

|

| |||||

| Pompe disease | GAA | - Glycogen accumulation and abnormal ultrastructure | Yes | (152) | |

|

| |||||

| FRDA | FXN | - Impaired iron homeostasis, mitochondrial damages and aberrant Ca2+ signaling | No | (153) | |

|

| |||||

| LEOPARD syndrome | PTPN11 | Abnormal cell size and sarcomeric organization | No | (51) | |

AP = action potential; ARVD = arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia; BTHS = Barth syndrome; CPVT = catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; FRDA = Friedreich ataxia; HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LQT = long QT syndrome;

Modeling a broken heart: use of iPSCs

Cardiomyopathy is a complex disease of the heart that has an etiology ranging from myocardial infarction, genetic mutations, endocrine disease, and drug toxicities. Historically, animal models have been used to understand the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases and discover new therapeutics. However, due to significant differences in cardiovascular genetics and physiology between humans and animals, there is a compelling need for more accurate models to understand cardiac diseases. The ability to differentiate iPSCs to disease-relevant derivatives, such as cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) (27,61), now offers a valuable opportunity to derive patient-specific cells for the purpose of cardiac disease modeling and drug discovery (28,62).

Human iPSC-CMs can serve as a disease model in a dish by retaining the genetic variance present in the patient and eventually exhibiting the phenotypic features of the disease in vitro. Indeed, several groups have used this iPSC-CM technology to model cardiac channelopathies, such as: long QT syndromes (53–55,63–65); Timothy syndrome (66); LEOPARD syndrome (51); catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) (67,68); arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD) (69,70); familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) (71); and familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) (72–74). In addition to understanding genetic cardiomyopathies, iPSC-CMs have also been used to model acquired or extrinsic cardiac diseases due to endocrine, metabolic, and neuromuscular dysfunction. For example, iPSC-CMs are being used in cell-based assays to model susceptibility to drug-induced cardiotoxicity (75,76), thereby allowing researchers to predict adverse drug responses more accurately in patients with different genetic backgrounds. Similarly, iPSC-CMs have been used to understand the disease progression of diabetic cardiomyopathy (77), viral myocarditis (78), cardiac hypertrophy (79), and genetic polymorphism-induced cardiac ischemia (80).

Disease modeling using iPSC-CMs has been feasible due to ever-improving differentiation protocols (27,29,81). Importantly, although the phenotypic characteristics of the iPSC-CMs are similar to those of primary human CMs with respect to their molecular, electrophysiological, mechanical, and metabolic properties, these functional characteristics also indicate that they resemble fetal, rather than adult CMs. Structurally, when compared to adult human CMs, these iPSC-CMs look much smaller in size and have less sarcomeric organization with decreased force generation (82–84). This could diminish their utility for modeling adult-related heart diseases. Table 2 summarizes the differences between immature and mature CMs.

Table 2.

Molecular, Electrophysiological, and Metabolic Profile of iPSC-CMs and Mature Cardiomyocytes

| Parameters | Immature CMs | Mature CMs | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Morphology | Shape | Round or polygonal | Rod and Elongated | (154) |

|

| ||||

| Size | 20–30 pF | 150 pF | (155) | |

|

| ||||

| Nuclei per cell | Mononucleated | ~25% multinucleated | (156) | |

|

| ||||

| Multicellular organization | Disorganized | Polarized | (155) | |

|

| ||||

| Sarcomere appearance | Disorganized | Organized | (155) | |

|

| ||||

| Sarcomere length | Shorter (~1.6 μm) | Longer (~2.2 μm) | (85) | |

|

| ||||

| Sarcomeric proteins | ||||

| - MHC | β >α | β >>α | (157) | |

| - Titin | N2BA | N2B | (158) | |

| - Troponin I | ssTnI | cTnI | (159) | |

|

| ||||

| Sarcomere units | ||||

| - Z-discs and I-bands | Formed | Formed | (155) | |

| - H-zones and A-bands | Formed (prolonged differentiation) | Formed | ||

| - M-bands and T-tubules | Absent | Present | (85) | |

|

| ||||

| Electrophysiology | Action potential properties | |||

| - Resting membrane potential | ~ −60mV | −90mV | (84) | |

| - Upstroke velocity | ~ 50 V/s | ~250 V/s | (137) | |

| - Amplitude | Small | Large | (155) | |

| - Spontaneous automaticity | Exhibited | Absent | (155) | |

| - Ion currents | ||||

| • Hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker (If) | Present | Absent | (137) | |

| • Sodium (INa) | Low | High | (160) | |

| • Inward rectifier potassium (IK1) | Low or absent | High | (137) | |

|

• Transient outward potassium current (Ito) | Inactivated | Activated | (161) |

| • ATP-sensitive K+ current (IK, ATP) | Not reported | Present | (162) | |

| • L- and T-type calcium (ICa,L and ICa,T), rapid and slow rectifier potassium currents (IKr and IKs), Na+−Ca+ exchange current (INCX) and acetylcholine-activated K+ (IK,ACh) | Similar to adult CMs | (84) | ||

|

| ||||

| Conduction Velocity | Propagation of signal | Slower (~0.1 m/s) | Faster (0.3–1.0 m/s) | (163) |

|

| ||||

| Gap junctions | Distribution | Circumferential | Polarized to intercalated disks | (164) |

|

| ||||

| Calcium handing | Ca2+ transient | Inefficient | Efficient | (165) |

|

| ||||

| Amplitudes of Ca2+ transient | Small and decrease with pacing | Increase with pacing | (166) | |

|

| ||||

| Excitation–Contraction coupling | Slow | Fast | (167) | |

|

| ||||

| Contractile force | ~nN range/cell | ~μN range/cell | (128) | |

|

| ||||

| Ca2+-handling proteins | ||||

| - CASQ2, RyR2, and PLN | Low or absent | Normal | (168) | |

|

| ||||

| Force-frequency relationship | Positive | Negative | (169) | |

|

| ||||

| Mitochondrial bioenergetics | Mitochondrial number | Low | High | (170) |

|

| ||||

| Mitochondrial volume | Low | High | (170) | |

|

| ||||

| Mitochondrial structure | Irregular distribution, perinuclear | Regular distribution, aligned | (171) | |

|

| ||||

| Mitochondrial proteins | ||||

| - DRP-1 and OPA1 | Low | High | (172) | |

|

| ||||

| Metabolic substrate | Glycolysis (glucose) | Oxidative (fatty acid) | (173) | |

|

| ||||

| Responses to β-adrenergic stimulation | Response | Lack of inotropic reaction | Inotropic reaction | (174) |

|

| ||||

| Cardiac alpha-adrenergic receptor ADRA1A | Absent | Present | (175) | |

ATP = adenosine triphosphate; CM = cardiomyocyte; MHC = major histocompatibility complex.

iPSC-CMs need to mature

In the developing heart, networks of diverse factors tightly regulate cardiomyocyte maturation, including mechanical, electrical, and biochemical signals. Although relatively simple expedients, such as keeping iPSC-CMs in culture for prolonged periods (85) or growing them on specific substrates (86), can enhance some aspects of their structure and functions, much research now focuses on uncovering factors and pathways that drive their maturation (87). Agents and cues that have been explored to induce maturation include microRNAs (88,89), chromatin and histone proteins (90), DNA methylation (91), metabolic energetics (92), and biochemical cues (93,94). By decoding these signaling pathways, substantial progress has been made in generating more mature iPSC-CMs. Additional future studies using high-throughput experiments would be necessary to unravel the complexity of full cardiac maturation. Unraveling these pathways could potentially allow us to mature iPSC-CMs in a dish, with closer resemblance to the adult human heart. However, it is unlikely that cells grown under in vitro conditions will fully resemble cells residing in intact living subjects, due to differences in environmental milieu, whether cardiac or noncardiac. Hence, expecting iPSC-CMs to be identical to mature primary human CMs may be unrealistic.

iPSCs and genome engineering: a perfect match

The emergence of genome editing tools, such as zinc finger nucleases (ZNFs), transcription activator–like effector nuclease (TALENs), and the clustered regularly-interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) (95), has further advanced the application of iPSC technology towards precision medicine. These genetic engineering techniques allow for deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) to be inserted, replaced, or removed from a genome using nucleases that create specific double-strand breaks at preferred locations. Endogenous cellular mechanisms then repair these breaks by homologous recombination (96). Using these tools, it is now possible to generate human cellular disease models in a precise and predictable manner. Indeed, genome editing has been used to introduce genetic alterations to create cardiac disease models or correct genetic mutations in iPSC-CMs to model cardiac diseases. Single genetic mutations responsible for cardiomyopathies, such as DCM, Barth syndrome (BTHS), long QT syndrome, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy have been corrected using these genome-editing tools (64,97–100), suggesting the feasibility of this approach for disease modeling. However, these engineered nucleases could introduce unintended genomic alterations; for example, in addition to cleaving the on-target site, they may have off-target effects. Similarly, other challenges, such as delivery methods and efficiency, still need to be sorted out (101). Taken together, this tag-team technology of patient-specific iPSCs and genome editing could lay the groundwork required to achieve the bold initiative of precision health (30).

Regenerative Medicine

The use of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), such as ESCs and iPSCs, for cell transplantation or organogenesis has captured the imagination of the lay public, but it remains a difficult task to achieve from a scientific standpoint. The limitation of organ transplantation, which is plagued by lack of organ availability and problems with immunorejection, has led researchers to find alternative approaches (9,15). Both ESCs and iPSCs could differentiate into any cell types in the body, and thus could potentially replace diseased or dysfunctional cells. Advances in culturing technology and differentiation protocols have produced much safer and clinically relevant cells with minimal tumorigenic risk (25). This enabled several groups to initiate clinical trials using pluripotent stem cells, with most targeting eye diseases (26). Of the 13 clinical trials being conducted, 9 are for ESC- or iPSC-RPE cells for macular degeneration, which causes the progressive deterioration of light-sensing photoreceptors in the eye (102). Earlier work had shown that iPSC- and ESC-RPE cells were safe and functional in preclinical models of macular degeneration (103,104). Similarly, iPSCs generated from patients suffering from retinitis pigmentosa (RP), a condition involving retinal degeneration, were able to differentiate to rod photoreceptor cells and have beneficial effects (105,106). Despite the excitement and momentum for the use of iPSC derivatives in clinical trial, a cautious approach is advisable, as one of the clinical trials focused on treating macular degeneration with iPSC-RPE cells was recently halted due to genetic mutations in the derived autologous cells. In addition, preclinical data using iPSCs have shown great promise for various other ailments, including hematopoietic disorders, spinal cord and musculoskeletal injury, and liver damage (107–110). As a comprehensive detailing of all these is beyond the scope of this review, we discuss only a few applications to cardiac diseases in the following sections.

Patching the broken heart

Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in humans. PSC-derived cardiac tissue may help restore diseased areas of the heart. Indeed, early work showed that PSC-CMs not only formed myocardial grafts, but also electrically coupled and partially remuscularized the infarcted areas, and improved myocardial performance in small animal models (111–114). Similarly, PSC-CMs have also shown promise in some preclinical large animal models (115). In a recent study, Chong et al. reported remuscularization of the infarcted region when human ESC-CMs were injected into nonhuman primate models of myocardial infarction (116). These grafts showed synchrony with the host myocardium, with regular calcium transients and electrical coupling after transplantation. However, ventricular arrhythmias were noted in these animals following transplantation, and the study failed to show an improvement in their cardiac function. Clearly, significant hurdles still need to be overcome to translate this preclinical report to a clinical trial. A much larger cohort of animals would be required to reach statistical power and allow more in-depth mechanical analyses of the engrafted heart, and the ventricular arrhythmias noted in these animals following transplantation need to be addressed before conducing human trials (117,118). To overcome the issues of poor engraftment and/or survival of transplanted cells, another study showed that a cytokine-loaded 3-dimensional (3D) fibrin patch with iPSC-derived cardiovascular cells (iPSC-CMs, iPSC-derived endothelial cells [iPSC-ECs], and iPSC-derived smooth muscle cells [iPSC-SMCs]) had a better chance of improving cardiac function in a pig model of myocardial infarction (115). One current clinical trial is actively recruiting patients to test the use of human ESC-derived cardiac progenitor cells in patients with heart failure (NCT02057900) (119). On the basis of their preclinical data showing a significant improvement in cardiac function due to paracrine effects of the transplanted cardiac progenitor cells (120), this ongoing clinical trial is using fibrin patches containing Isl-1+ SSEA-1+ cells. The trial's first clinical case report has found improvement in patient's functional outcomes and evidence of new-onset contractility of the transplanted area (121). However, the evaluation of efficacy remains speculative, as these ESC-fibrin patches were implanted at the time of a coronary artery bypass graft procedure. Accordingly, more patients need to be recruited and randomized trials need to be performed in the future.

Tissue engineering: to the rescue of cell therapy

It has become quite clear in the past few years that without optimal bioengineering tools, the use of PSC-CMs for regenerative medicine may be limited. This is evident, given that previous studies using PSC-CMs or progenitor cells have only seen moderate success due to the failure of cells either to survive transplantation or to fully engraft into the host myocardium, limiting possible gains in cardiac function (122). Similarly, misalignment of the engrafted cardiac cells with the host myocardium increases the risk of ventricular arrhythmias due to electrical heterogeneity (116,117,123). A patch-based approach for cardiac repair may be more advantageous than intramyocardial injections because the patch could simultaneously act as a substrate to strengthen the injured myocardium and prevent adverse remodeling, and also provide a template for cells to survive and even proliferate. With advances in tissue bioengineering, diverse biomaterials have been found with the potential to enhance cardiac cell therapy (124). These biomaterials (including collagen, fibrin, alginates, silk, decellularized heart matrix, and synthetic polymers) now allow researchers to deliver cells, retain them in situ, and use them to replace scar tissue with a large number of stem cell derivatives. In addition to being a vehicle for cell delivery, cardiac patches have been shown to stimulate endogenous paracrine factors that assist in cardiac repair (125,126).

Although there is much enthusiasm for the use of engineered heart tissue constructed from PSC-CMs for cardiac repair, there are some limitations that need to be addressed, including engineering tissues that are simultaneously large enough to provide benefits, but small enough to prevent death of the transplanted cells due to lack of oxygen and nutrients. Even transplanted engineered heart muscle constructs showed poor survivability due to lack of vascularization (127). Hence pre-vascularization of the in vitro heart tissue could potentially make these engineered patches more closely resemble the native human myocardium and allow survival of thicker tissues. Indeed, the addition of human endothelial cells (ECs) to ESC-CMs enhanced formation of vessel-like structures and CM proliferation in vitro (128). Similarly, the addition of a vascular patch comprised of human ESC-ECs and ESC-SMCs to a porcine model of myocardial infarction resulted in significant improvements in cardiac function (129). Taken together, the continuing progress made in tissue engineering to promote cell engraftment and survival following transplantation is expected to take us yet another step closer to the clinical use of PSC-CMs in regenerative medicine.

Drug Discovery and Toxicity Screening

In the past, immortalized cell lines or experimental animal models have been used to screen therapeutics for human diseases, with limited success due to differences from the actual human setting. For example, it has always been difficult to analyze and compare data between mice and humans for cardiac diseases, given the considerable variation in their heart rates (e.g., mice exhibit a higher heart rate of 500 to 600 beats/min, compared with human heart rates of 60 to 70 beats/min) and electrophysiological properties (e.g., mice have shorter action potentials compared with humans due to differences in cardiac ion channels) (130). Studies using patient's primary heart tissue are helpful, but are limited due to lack of donor availability, making in vitro modeling using this approach difficult, and thus hampering its use in the evaluation of drug efficacy and toxicity.

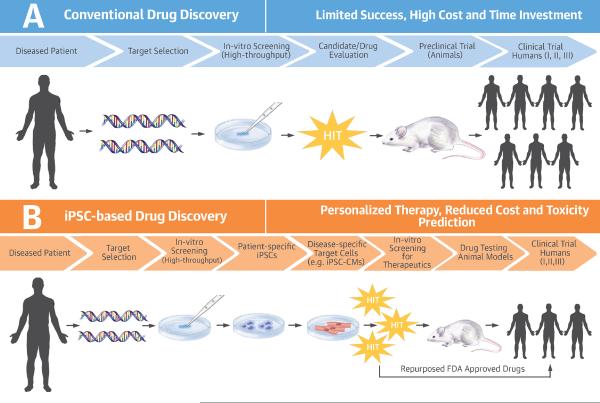

Conventional drug screening: a long, arduous road

There has been a long list of high-profile drugs that have been withdrawn from the market due to their off-target and on-target toxicity to the heart, including the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug rofecoxib (Vioxx; Merck & Co, Kenilworth, NJ, USA), gastrointestinal prokinetic drug cisapride (Propulsid; Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA), and broad-spectrum antibacterial drug grepafloxacin (Raxar; GSK, Brentford, UK), all of which were withdrawn due to clinical cardiac and/or arrhythmogenic toxicities (131). With the pharmaceutical industry investing ~$2 billion per new drug over a period of 10 to 15 years (132), this situation creates a tremendous burden on the healthcare system. The drug withdrawals are partly attributable to drug safety studies being evaluated in less than ideal nonhuman animal cells and models after years of laboratory and preclinical testing (Figure 2). The pharmaceutical industry typically conducts their cardiotoxicity studies of new drugs using in vitro cell lines, such as Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells overexpressing the IKr protein hERG (human Ether-à-go-go-Related Gene) (133,134). However, these in vitro cell lines do not replicate human CMs well, and the overexpression of a single cardiac ion channel in these cells does not recapitulate the complex channel biology in CMs. Due to these limitations, there is an inherent risk of cardiotoxic drugs slipping through initial screens, only to be subsequently withdrawn from the market after patients have suffered harm and large investments have been incurred or wasted. Moreover, the converse may also be true. It is possible that preclinical testing of certain drugs using in vitro cell lines may show toxicity, only for the same drug to be later shown to be safe and efficacious for human usage (e.g., verapamil) (75,131). This could lead to valuable drugs not being marketed or developed at all due to inaccurate forecasting of their likely toxic effects using conventional approaches.

Figure 2. Conventional Versus iPSC-based Drug Discovery.

The conventional drug discovery pathway is a very inefficient process with a high attrition rate. The majority of drug candidates never reach the market due to safety and efficacy issues. This is partly attributed to the lack of appropriate drug development models that could accurately predict drug efficacy, and partly due to dependence on animal models of disease that do not replicate human pathophysiology. By comparison, iPSC technology allows high-throughput screening of therapeutic molecules by providing disease-specific drug development models that are generated from the patients themselves. This makes iPSC technology a much better predictive tool, and allows well-informed decisions to be made earlier in the drug development process. FDA = Food and Drug Administration; iPSC = induced pluripotent stem cell; iPSC-CM = induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte.

With all these known roadblocks in conventional drug screening, there is a compelling need to use functional human CMs for drug screening. PSC-CMs have now been comprehensively characterized as a good model for cardiotoxicity studies. Using a standard protocol, electrophysiological responses of PSC-CMs to a selection of known drugs that affect the hERG channel have shown comparable data to conventional hERG using in vitro assays (135,136). These studies indicate that PSC-CMs could be adopted as a standard model for cardiotoxicity studies. Importantly for pharmaceutical companies, this model could be a suitable addition to their conventional drug screening methods.

iPSC-based drug screening: it's precise, it's personal

Every patient has a unique genetic background and reacts differently to medications. Despite presenting with similar symptoms, patients might have different underlying etiologies for the disease, but, conventionally, they will still receive the same medication on the basis of their symptoms. iPSC-based drug screening technology may allow evaluation of a personalized therapy for every patient, an approach known as precision medicine (30).

With the advent of iPSCs (9) and the improvements in differentiating iPSCs to functional CMs (27,29,81), it is now feasible to generate functional human CMs for drug screening, thereby avoiding the issues associated with earlier, less relevant screening systems, thus minimizing the time/cost for drug development. These ESC-CMs and iPSC-CMs have been thoroughly characterized to show similar electrophysiological, biochemical, and pharmacological functions certifying them as bona fide CMs (137). In addition, PSC-CMs could be cultured in a dish for extended periods of time (138), and large-scale production of PSC-CMs is feasible from healthy controls or patients suffering from various cardiac diseases (Table 1). This iPSC-based model could provide a valuable tool for the preclinical screening of candidates that have therapeutic value and for screening candidates that might have off-target cardiac toxicity in any individual genotype, taking us one step closer to the goal of bringing precision medicine to the clinic (Figure 2).

Although PSC-CMs provide an excellent platform for drug screening and toxicology studies (135), they currently have several limitations. For example, PSC-CMs are generally immature and resemble fetal CMs, both structurally and electrophysiologically (84,139). This cellular immaturity issue may seriously limit drug development using PSCs. To overcome this limitation, several approaches have been developed to mature PSC-CMs, including differentiating them on 3D patches, which could enhance the CMs' contractile apparatus (87,140). Others have tried to achieve maturity by overexpressing microRNAs (miR-1/miR-499, Let7) to improve metabolic energetics (88,92) or by subjecting the cells to electrical and mechanical stimulation (141). In addition, uniaxial stretching of engineered heart muscle made from PSC-CMs could enhance their viability and maturation, and has been used for drug screening (142). Despite their resemblance to fetal CMs and their label as “immature” CMs, these PSC-CMs have been successfully used to study drug efficacy and toxicity (75,76).

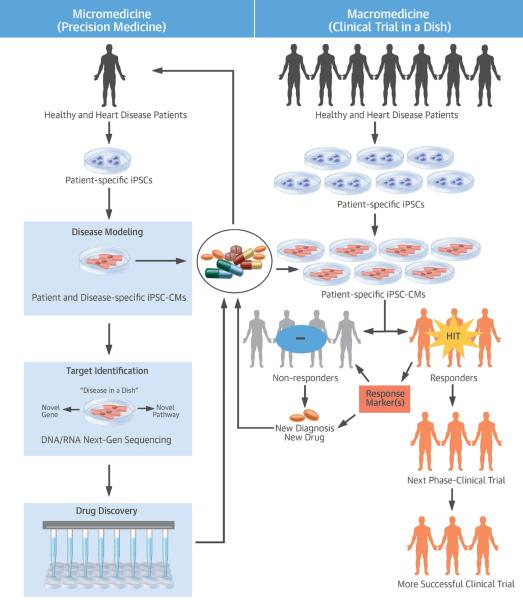

iPSC clinical trials: towards macromedicine

As described previously, iPSC technology has revolutionized the concept of precision medicine. Earlier, due to the lack of available human samples, drug toxicity screening was difficult and relied heavily on immortalized cell-based assay or in vivo animal models. However, advances in iPSC technology could provide a steady supply of functional cells for preclinical screening of drugs. Moreover, iPSCs provide a unique platform that enables researchers to model diseases on a patient-by-patient basis. This “micromedicine” approach makes it possible to understand disease progression at an individual patient level, and thus to screen for optimal pharmacological drugs individually. Beyond analyses performed for individual patients, high-throughput assays for drug toxicity using human iPSC-CMs (143) can also be conducted, supporting the role that iPSC technology can play in “macromedicine,” under which iPSC-based medicine could be applied to cohorts of patients (144). In these clinical trials, iPSCs generated from patients could be differentiated into functional cells and then used to analyze the efficacy of drugs (Central Illustration). On this basis, patients could be classified as drug responders or nonresponders, and only those patients responding to the specific drugs would be moved to the next phase of the clinical trial. Thus, iPSCs could provide valuable patient stratification on the basis of drug each patient's responsiveness in the clinical trials. Moreover, iPSCs could help us identify specific markers in the drug responders corresponding to important patient subpopulations, thereby boosting the success rate in clinical trials by pre-selecting patients who will benefit. Taken together, iPSC technology has the potential to significantly contribute to or even revolutionize macromedicine, for the first time allowing us to quickly and correctly identify a subset of patients with specific diseases responding the drugs under study. Similarly, depending on the effectiveness of the drug in clinical trials, we may also gain the ability to diagnose sporadic diseases among a subset of patients. Given that iPSC-based clinical trials are in their infancy, much work is still needed to rapidly and economically develop personalized iPSCs.

Precision Medicine: the right drug for the right patient at the right dose

The practice of medicine is undergoing a fundamental change. Rather than a generalized approach, the diagnostic and therapeutic strategies are now patient-oriented with focus on precision medicine (30). This involves integrating patient's “omics” information (e.g., genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic) with advances in medical technology to tailor therapeutic options for every individual patient. With the advent of iPSC technology, this endeavor of precision medicine is now feasible.

There is an overwhelming consensus that cardiology will lead the development of precision medicine, after decades of research have revealed many of the molecular pathways that cause cardiomyopathies. Moreover, the use of iPSC-derived cardiovascular cells have now enabled researchers to understand the underlying mechanisms of many cardiac diseases that were difficult to model due to lack of patient samples. This new understanding has started to influence diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for cardiac diseases by the use of drugs that target specific molecular drivers. For example, the phenotype of iPSC-CMs derived from patients with long QT syndrome were found to be affected by β-adrenergic receptor blockers (53). Similarly, a drug for malignant hyperthermia, dantrolene, was found to restore the abnormal Ca2+ sparks and arrhythmogenic phenotype of iPSC-CMs derived from CPVT patients (67). Such genotype-guided therapy is precise and, if applied on a large scale, can transform patient care.

To achieve a deeper understanding of complex genetic cardiomyopathies, many more cardiac genomes need to be analyzed. This will require advances in medical technology that can help us better understand heart disease and are capable of predicting an optimal treatment plan for each patient. With the availability of next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics, patient-specific iPSC-based pharmacogenomics can provide such valuable information. Patient's iPSC-CMs could help identify the genetic basis of the disease, followed by disease modeling, and finally, leading to the identification of pharmacogenetic biomarkers that can facilitate effective drug therapy. This information, once collected, can be matched with drug discovery screens to predict the most effective drug treatment (combination) for each person. In conclusion, patient-specific iPSC disease modeling and iPSC-based pharmacogenomics have the potential to identify patient-specific genetic loci that are responsible for disease, and help developing the optimal individualized therapeutics for each patient.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Since the initial basic discovery by Dr. Shinya Yamanaka that a set of 4 transcription factors could reprogram mouse and human somatic cells to pluripotency (8,9), the field of iPSCs, free from the ethical issues associated with ESCs, has successfully expanded to different avenues of regenerative medicine. To date, iPSCs have 3 major applications in disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine (145). Human iPSC-CMs have been used extensively to characterize and model human heart diseases (146). There have been more than 700 publications in the last few years expanding their use to additional human diseases (both monogenic and polygenic). These advances in cardiac disease modeling have been made possible due to tissue-specific differentiation protocols allowing researchers to derive healthy and disease-specific CMs (Table 1). In addition to disease modeling, several groups have tried to inject PSC-CMs into small and large animal models of myocardial infarction, with variable levels of success. Concerted efforts are now underway to further enhance the preclinical outcome of these PSC-CMs when transplanted into animal models of cardiac diseases. PSC-CMs also provide a unique platform to conduct drug-screening assays and to discover novel therapeutics. However, a major concern thus far is the immature status of the PSC-CMs. Various approaches, including cardiac tissue bioengineering have been utilized to mature these PSC-CMs. Finally, the availability of genetically affected human tissues is very limited. Genome-edited pluripotent stem cell lines have now made it possible to recapitulate the human disease in a dish using various gene-editing tools, such as endonucleases (ZFN or TALEN) or palindromic repeats (CRISPR). Libraries of disease-specific cells can now be generated by creating allele-specific patient iPSC lines to conduct drug testing and toxicity studies. In summary, iPSC technology is not only revolutionizing science, but will also fundamentally alter our health care system and the future of medicine by making it proactive, predictive, preventive, and personalized.

Central Illustration: iPSC Clinical Trial: From Micromedicine to Macromedicine.

iPSC technology has contributed to both micromedicine and macromedicine. This includes disease modeling and drug development on the basis of cellular and molecular analyses of individual patients to iPSC clinical trials for stratification on the basis of cellular and molecular analyses of a cohort of patients. Importantly, it could allow a more precise clinical trial by identifying a subset of patients with a specific disease who optimally respond to the drugs under investigation, thereby boosting success rates by pre-selecting these drug responders. DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid; iPSC = induced pluripotent stem cell; iPSC-CM = induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte; RNA = ribonucleic acid.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Joseph Gold, Jon Stacks, and Blake Wu for critical reading of the manuscript, and Amy Thomas for preparing the illustrations. Due to space constraints, the authors could not include all the relevant citations on the subject matter, for which they apologize.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 HL126527, NIH R01 HL123968, NIH R01 HL128170, and NIH R01 HL130020 to Dr. Wu; and American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (13SDG17340025), NIH-NHLBI PCBC Pilot grant (SR00003169/5U01HL099997), and a Stanford CVI Seed Grant to Dr. Sayed.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- CM

cardiomyocyte

- CRISPR

clustered regularly-interspaced short palindromic repeats

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- EC

endothelial cell

- ESC

embryonic stem cell

- iPSC

induced pluripotent stem cell

- iPSC-CM

induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte

- PSC

pluripotent stem cell

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Wu is co-founder of Stem Cell Theranostics and has received a research grant from Sanofi. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.Till JE, McCulloch EA. A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat Res. 1961;14:213–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurdon JB. The developmental capacity of nuclei taken from intestinal epithelium cells of feeding tadpoles. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1962;10:622–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilmut I, Schnieke AE, McWhir J, et al. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature. 1997;385:810–3. doi: 10.1038/385810a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–6. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–7. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tada M, Takahama Y, Abe K, et al. Nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells by in vitro hybridization with ES cells. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1553–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis RL, Weintraub H, Lassar AB. Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell. 1987;51:987–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006. 126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marson A, Foreman R, Chevalier B, et al. Wnt signaling promotes reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:132–5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huangfu D, Maehr R, Guo W, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells by defined factors is greatly improved by small-molecule compounds. Nat Biotech. 2008;26:795–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321:1218–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanna J, Markoulaki S, Schorderet P, et al. Direct reprogramming of terminally differentiated mature B lymphocytes to pluripotency. Cell. 2008;133:250–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun N, Panetta NJ, Gupta DM, et al. Feeder-free derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from adult human adipose stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15720–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908450106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Y, Yin X, Qin H, et al. Two supporting factors greatly improve the efficiency of human iPSC generation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:475–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woltjen K, Michael IP, Mohseni P, et al. piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:766–70. doi: 10.1038/nature07863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carey BW, Markoulaki S, Hanna J, et al. Reprogramming of murine and human somatic cells using a single polycistronic vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:157–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811426106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia F, Wilson KD, Sun N, et al. A nonviral minicircle vector for deriving human iPS cells. Nat Methods. 2010;7:197–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wernig M, Lengner CJ, Hanna J, et al. A drug-inducible transgenic system for direct reprogramming of multiple somatic cell types. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:916–24. doi: 10.1038/nbt1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:618–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou H, Wu S, Joo JY, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:381–4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J, Sayed N, Hunter A, et al. Activation of innate immunity is required for efficient nuclear reprogramming. Cell. 2012;151:547–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hou P, Li Y, Zhang X, et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science. 2013;341:651–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1239278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neofytou E, O'Brien CG, Couture LA, et al. Hurdles to clinical translation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2551–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI80575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimbrel EA, Lanza R. Current status of pluripotent stem cells: moving the first therapies to the clinic. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:681–92. doi: 10.1038/nrd4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burridge PW, Keller G, Gold JD, et al. Production of de novo cardiomyocytes: Human pluripotent stem cell differentiation and direct reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsa E, Burridge PW, Wu JC. Human stem cells for modeling heart disease and for drug discovery. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:239ps6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burridge PW, Matsa E, Shukla P, et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods. 2014;11:855–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:793–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polo JM, Anderssen E, Walsh RM, et al. A molecular roadmap of reprogramming somatic cells into iPS cells. Cell. 2012;151:1617–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buganim Y, Faddah DA, Cheng AW, et al. Single-cell expression analyses during cellular reprogramming reveal an early stochastic and a late hierarchic phase. Cell. 2012;150:1209–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rais Y, Zviran A, Geula S, et al. Deterministic direct reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Nature. 2013;502:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nature12587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chin MH, Mason MJ, Xie W, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells are distinguished by gene expression signatures. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:111–23. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh Z, Wilson KD, Wu Y, et al. Persistent donor cell gene expression among human induced pluripotent stem cells contributes to differences with human embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deng J, Shoemaker R, Xie B, et al. Targeted bisulfite sequencing reveals changes in DNA methylation associated with nuclear reprogramming. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:353–60. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bock C, Kiskinis E, Verstappen G, et al. Reference maps of human ES and iPS cell variation enable high-throughput characterization of pluripotent cell lines. Cell. 2011;144:439–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guenther MG, Frampton GM, Soldner F, et al. Chromatin structure and gene expression programs of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newman AM, Cooper JB. Lab-specific gene expression signatures in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:258–62. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi J, Lee S, Mallard W, et al. A comparison of genetically matched cell lines reveals the equivalence of human iPSCs and ESCs. Nat Biotech. 2015;33:1173–81. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sayed N, Wong WT, Cooke JP. Therapeutic transdifferentiation: can we generate cardiac tissue rather than scar after myocardial injury? Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2013;9:210–2. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-9-4-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, et al. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 2010;463:1035–41. doi: 10.1038/nature08797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang P, He Z, Ji S, et al. Induction of functional hepatocyte-like cells from mouse fibroblasts by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:386–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ieda M, Fu JD, Delgado-Olguin P, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Margariti A, Winkler B, Karamariti E, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into endothelial cells capable of angiogenesis and reendothelialization in tissue-engineered vessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13793–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205526109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sayed N, Wong WT, Ospino F, et al. Transdifferentiation of human fibroblasts to endothelial cells: role of innate immunity. Circulation. 2015;131:300–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen JX, Krane M, Deutsch MA, et al. Inefficient reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes using Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5. Circ Res. 2012;111:50–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.270264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ebert AD, Diecke S, Chen IY, et al. Reprogramming and transdifferentiation for cardiovascular development and regenerative medicine: where do we stand? EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:1090–103. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201504395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merkle Florian T, Eggan K. Modeling human disease with pluripotent stem cells: from genome association to function. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:656–68. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, et al. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:877–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carvajal-Vergara X, Sevilla A, D'Souza SL, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature. 2010;465:808–12. doi: 10.1038/nature09005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marchetto MCN, Winner B, Gage FH. Pluripotent stem cells in neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R71–6. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moretti A, Bellin M, Welling A, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1397–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I, et al. Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:225–9. doi: 10.1038/nature09747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matsa E, Rajamohan D, Dick E, et al. Drug evaluation in cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells carrying a long QT syndrome type 2 mutation. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:952–62. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Narsinh K, Narsinh KH, Wu JC. Derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells for cardiovascular disease modeling. Circ Res. 2011;108:1146–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.240374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Filareto A, Parker S, Darabi R, et al. An ex vivo gene therapy approach to treat muscular dystrophy using inducible pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1549. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin B, Li Y, Han L, et al. Modeling and study of the mechanism of dilated cardiomyopathy using induced pluripotent stem cells derived from individuals with duchenne muscular dystrophy. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8:457–66. doi: 10.1242/dmm.019505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raya Á , Rodríguez-Pizà I, Guenechea G, et al. Disease-corrected haematopoietic progenitors from fanconi anaemia induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;460:53–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Urbach A, Bar-Nur O, Daley GQ, et al. Differential modeling of fragile X syndrome by human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:407–11. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burridge PW, Holmström A, Wu JC. Chemically defined culture and cardiomyocyte differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2015;87:21.3.1–21.3.15. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg2103s87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mordwinkin NM, Lee AS, Wu JC. Patient-specific stem cells and cardiovascular drug discovery. JAMA. 2013;310:2039–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Egashira T, Yuasa S, Suzuki T, et al. Disease characterization using LQTS-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:419–29. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Y, Liang P, Lan F, et al. Genome editing of isogenic human induced pluripotent stem cells recapitulates long QT phenotype for drug testing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:451–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lahti AL, Kujala VJ, Chapman H, et al. Model for long QT syndrome type 2 using human iPS cells demonstrates arrhythmogenic characteristics in cell culture. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5:220–30. doi: 10.1242/dmm.008409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yazawa M, Hsueh B, Jia X, et al. Using induced pluripotent stem cells to investigate cardiac phenotypes in Timothy syndrome. Nature. 2011;471:230–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jung CB, Moretti A, Mederos y Schnitzler M, et al. Dantrolene rescues arrhythmogenic RYR2 defect in a patient-specific stem cell model of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:180–91. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Novak A, Barad L, Zeevi-Levin N, et al. Cardiomyocytes generated from CPVTD307H patients are arrhythmogenic in response to β-adrenergic stimulation. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:468–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim C, Wong J, Wen J, et al. Studying arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia with patient-specific iPSCs. Nature. 2013;494:105–10. doi: 10.1038/nature11799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Asimaki A, Kapoor S, Plovie E, et al. Identification of a new modulator of the intercalated disc in a zebrafish model of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:240ra74. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lan F, Lee AS, Liang P, et al. Abnormal calcium handling properties underlie familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:101–13. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun N, Yazawa M, Liu J, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:130ra47. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu H, Lee J, Vincent LG, et al. Epigenetic regulation of phosphodiesterases 2A and 3A underlies compromised β-adrenergic signaling in an iPSC model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hinson JT, Chopra A, Nafissi N, et al. Titin mutations in iPS cells define sarcomere insufficiency as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Science. 2015;349:982–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Navarrete EG, Liang P, Lan F, et al. Screening drug-induced arrhythmia using human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes and low-impedance microelectrode arrays. Circulation. 2013;128:S3–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liang P, Lan F, Lee AS, et al. Drug screening using a library of human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes reveals disease-specific patterns of cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2013;127:1677–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Drawnel FM, Boccardo S, Prummer M, et al. Disease modeling and phenotypic drug screening for diabetic cardiomyopathy using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep. 2014;9:810–21. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sharma A, Marceau C, Hamaguchi R, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes as an in vitro model for coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis and antiviral drug screening platform. Circ Res. 2014;115:556–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aggarwal P, Turner A, Matter A, et al. RNA expression profiling of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes in a cardiac hypertrophy model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ebert AD, Kodo K, Liang P, et al. Characterization of the molecular mechanisms underlying increased ischemic damage in the aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 genetic polymorphism using a human induced pluripotent stem cell model system. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:255ra130. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lian X, Zhang J, Azarin SM, et al. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:162–75. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang J, Wilson GF, Soerens AG, et al. Functional cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Res. 2009;104:e30–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang X, Pabon L, Murry CE. Engineering adolescence: Maturation of human pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2014;114:511–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Karakikes I, Ameen M, Termglinchan V, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: insights into molecular, cellular, and functional phenotypes. Circ Res. 2015;117:80–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lundy SD, Zhu WZ, Regnier M, et al. Structural and functional maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:1991–2002. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jacot JG, McCulloch AD, Omens JH. Substrate stiffness affects the functional maturation of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 2008;95:3479–87. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.124545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tzatzalos E, Abilez OJ, Shukla P, et al. Engineered heart tissues and induced pluripotent stem cells: macro- and microstructures for disease modeling, drug screening, and translational studies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;96:234–44. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fu JD, Rushing SN, Lieu DK, et al. Distinct roles of microRNA-1 and -499 in ventricular specification and functional maturation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wilson KD, Hu S, Venkatasubrahmanyam S, et al. Dynamic microRNA expression programs during cardiac differentiation of human embryonic stem cells: role for miR-499. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:426–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.934281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang CL, McKinsey TA, Chang S, et al. Class II histone deacetylases act as signal-responsive repressors of cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 2002;110:479–88. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00861-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gilsbach R, Preissl S, Grüning BA, et al. Dynamic DNA methylation orchestrates cardiomyocyte development, maturation and disease. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5288. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kuppusamy KT, Jones DC, Sperber H, et al. Let-7 family of microRNA is required for maturation and adult-like metabolism in stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E2785–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424042112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Földes G, Mioulane M, Wright JS, et al. Modulation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte growth: A testbed for studying human cardiac hypertrophy? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:367–76. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chattergoon NN, Giraud GD, Louey S, et al. Thyroid hormone drives fetal cardiomyocyte maturation. FASEB J. 2012;26:397–408. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-179895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim H, Kim JS. A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:321–34. doi: 10.1038/nrg3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Esvelt KM, Wang HH. Genome-scale engineering for systems and synthetic biology. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:641. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Karakikes I, Stillitano F, Nonnenmacher M, et al. Correction of human phospholamban R14del mutation associated with cardiomyopathy using targeted nucleases and combination therapy. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6955. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang G, McCain ML, Yang L, et al. Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of Barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart-on-chip technologies. Nat Med. 2014;20:616–23. doi: 10.1038/nm.3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bellin M, Casini S, Davis RP, et al. Isogenic human pluripotent stem cell pairs reveal the role of a KCNH2 mutation in long-QT syndrome. EMBO J. 2013;32:3161–75. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Long C, McAnally JR, Shelton JM, et al. Prevention of muscular dystrophy in mice by CRISPR/Cas9–mediated editing of germline DNA. Science. 2014;345:1184–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1254445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cox DBT, Platt RJ, Zhang F. Therapeutic genome editing: prospects and challenges. Nat Med. 2015;21:121–31. doi: 10.1038/nm.3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] National Library of Medicine; Bethesda, MD: [Accessed February 27, 2016]. 2000–2016. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lu B, Malcuit C, Wang S, et al. Long-term safety and function of RPE from human embryonic stem cells in preclinical models of macular degeneration. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2126–35. doi: 10.1002/stem.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kamao H, Mandai M, Okamoto S, et al. Characterization of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium cell sheets aiming for clinical application. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;2:205–18. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yoshida T, Ozawa Y, Suzuki K, et al. The use of induced pluripotent stem cells to reveal pathogenic gene mutations and explore treatments for retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Brain. 2014;7:45. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Li Y, Tsai YT, Hsu CW, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of human-induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS) grafts in a preclinical model of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Med. 2012;18:1312–9. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2012.00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu H, Kim Y, Sharkis S, et al. In vivo liver regeneration potential of human induced pluripotent stem cells from diverse origins. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:82ra39. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nori S, Okada Y, Yasuda A, et al. Grafted human-induced pluripotent stem-cell–derived neurospheres promote motor functional recovery after spinal cord injury in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16825–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108077108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tan Q, Lui PPY, Rui YF, et al. Comparison of potentials of stem cells isolated from tendon and bone marrow for musculoskeletal tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;18:840–51. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Suzuki N, Yamazaki S, Yamaguchi T, et al. Generation of engraftable hematopoietic stem cells from induced pluripotent stem cells by way of teratoma formation. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1424–31. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, et al. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015–24. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Caspi O, Huber I, Kehat I, et al. Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes improves myocardial performance in infarcted rat hearts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1884–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fernandes S, Naumova AV, Zhu WZ, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes engraft but do not alter cardiac remodeling after chronic infarction in rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:941–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shiba Y, Fernandes S, Zhu WZ, et al. Human ES-cell-derived cardiomyocytes electrically couple and suppress arrhythmias in injured hearts. Nature. 2012;489:322–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ye L, Chang YH, Xiong Q, et al. Cardiac repair in a porcine model of acute myocardial infarction with human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiovascular cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:750–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chong JJH, Yang X, Don CW, et al. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature. 2014;510:273–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Anderson ME, Goldhaber J, Houser SR, et al. Embryonic stem cell–derived cardiac myocytes are not ready for human trials. Circ Res. 2014;115:335–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.304616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Murry CE, Chong JJH, Laflamme MA. Letter by Murry et al regarding article, “Embryonic stem cell–derived cardiac myocytes are not ready for human trials”. Circ Res. 2014;115:e28–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.305042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris . ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] National Library of Medicine; Bethesda, MD: [Accessed February 27, 2016]. 2015. Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-derived Progenitors in Severe Heart Failure (ESCORT) Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02057900. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bellamy V, Vanneaux V, Bel A, et al. Long-term functional benefits of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac progenitors embedded into a fibrin scaffold. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34:1198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Menasché P, Vanneaux V, Hagège A, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac progenitors for severe heart failure treatment: first clinical case report. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2011–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wang X, Jameel MN, Li Q, et al. Stem cells for myocardial repair with use of a transarterial catheter. Circulation. 2009;120:S238–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.885236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Pijnappels DA, Schalij MJ, Atsma DE, et al. Cardiac anisotropy, regeneration, and rhythm. Circ Res. 2014;115:e6–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ye L, Zimmermann WH, Garry DJ, et al. Patching the heart: cardiac repair from within and outside. Circ Res. 2013;113:922–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Xiong Q, Ye L, Zhang P, et al. Bioenergetic and functional consequences of cellular therapy: activation of endogenous cardiovascular progenitor cells. Circ Res. 2012;111:455–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]