Abstract

Despite recent advances in modern medicine, castration-resistant prostate cancer remains an incurable disease. Subpopulations of prostate cancer cells develop castration-resistance by obtaining the complete steroidogenic ability to synthesize androgens from cholesterol. Statin derivatives, such as simvastatin, inhibit cholesterol biosynthesis and may reduce prostate cancer incidence as well as progression to advanced, metastatic phenotype. In this study, we demonstrate novel simvastatin-related molecules SVA, AM1, and AM2 suppress the tumorigenicity of prostate cancer cell lines including androgen receptor-positive LNCaP C-81 and VCaP as well as androgen receptor-negative PC-3 and DU145. This is achieved through inhibition of cell proliferation, colony formation, and migration as well as induction of S-phase cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. While the compounds effectively block androgen receptor signaling, their mechanism of inhibition also includes suppression of the AKT pathway, in part, through disruption of the plasma membrane. SVA also possess an added effect on cell growth inhibition when combined with docetaxel. In summary, of the compounds studied, SVA is the most potent inhibitor of prostate cancer cell tumorigenicity, demonstrating its potential as a promising therapeutic agent for castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Keywords: AKT, Androgen Receptor, ErbB-2, Cholesterol, Simvastatin

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa)1 is the most frequently diagnosed tumor and second leading cause of cancer-related fatality among United States men [1]. The majority of prostate tumors are reliant on androgen signaling for their development and progression, thus ADT is an effective means of treatment and remains the current standard-of-care therapy for metastatic PCa [2,3]. However, most patients ultimately relapse: cancer cells are able to endure the androgen-depleted environment and develop CR tumors for which the median life-expectancy is less than 19 months. Despite advancements in post-ADT therapy, CR PCa remains an incurable disease maintaining an immediate need for advancement in treatment strategies [4,5].

Though CR tumors are no longer responsive to ADT, the majority continue to rely on AR signaling for growth and progression [3,6-8]. While the mechanism through which tumor cells acquire castration-resistance may vary, one mechanism is the development of intracrine regulation by activating the androgen biosynthesis pathway. [6,7,9,10]. For example, AR-positive LNCaP C-81 cells acquire the complete steroidogenic ability to synthesize androgens from cholesterol and obtain the CR phenotype [11]. This suggests inhibitors of steroid biosynthesis such as statins, which suppress cholesterol production via inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase, can be effective therapeutic agents for this population of tumors [12]. Supportively, ADT combined with simvastatin, a statin compound, reduces tumor growth and delays CR progression in murine models [13]. Moreover, epidemiological studies have reported a significant correlation between statin use and overall reduced risk of PCa diagnosis in addition to decreased development of aggressive, metastatic phenotype. [14]. Meta-analyses of observational studies have found ADT and/or radiotherapy combined with statin treatment resulted in a higher recurrence-free survival rate [15,16]. Together, these findings support the usage of statins to treat CR PCa patients. Importantly, FDA-approved cholesterol lowering drugs, such as simvastatin, possess well tolerated side-effect profiles [17]. This makes statins an ideal treatment option and suggests they can be combined with existing chemotherapeutic agents with minimal additional risk to the patient.

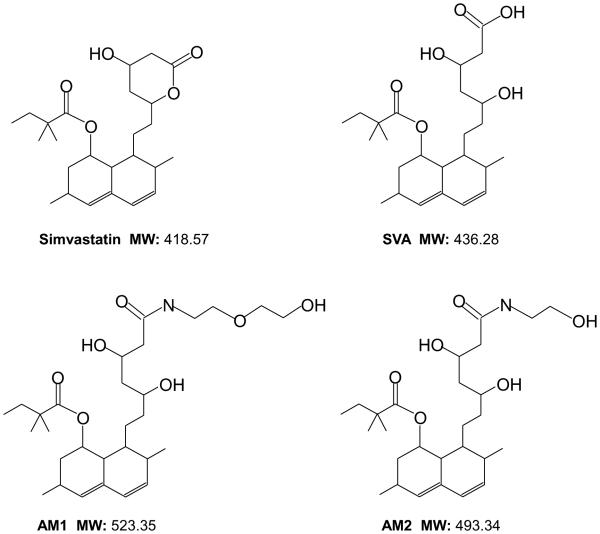

Currently, the mechanism of statin-mediated inhibition of PCa tumorigenicity remains poorly understood; further investigation using clinically-relevant cell line models is required. Moreover, PCa research on statins is frequently conducted using concentrations well-exceeding what is clinically relevant to achieve significant data, indicating a need for more potent statin derivatives [18]. In this study, we investigate the efficacy of novel statin derivatives SVA, AM1, and AM2 (Fig. 1) as therapeutic agents for CR PCa with the goal of producing a more potent compound to effectively treat CR PCa. SVA is a potent metabolite of simvastatin, while AM1 and AM2 are amide modified statin derivatives with lower HMG-CoA reductase inhibition [19]. In addition, we use LNCaP C-81 cells as our primary cell model because they are a useful representative of advanced CR PCa: they express functional AR as well as readily proliferate and secrete PSA under SR conditions which strongly correlates with clinical CR PCa phenotype [20-22]. Furthermore, C-81 cells exhibit intracrine growth regulation in which the cells possess the ability to synthesize androgens from cholesterol [11]. This acquired steroidogenic ability provides a mechanism of escape from ADT and development of castration-resistance. In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that the novel statin compound SVA is a potent inhibitor of CR PCa cells and investigate its mechanism of tumor suppression using clinically relevant cell line models.

Figure 1. Structures of statin derivatives.

Simvastatin, simvastatin hydroxyacid (SVA), 8-(3,5-dihydroxy-7-((2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethyl)amino)-7-oxoheptyl)-3,7-dimethyl-1,2,3,7,8,8a-hexahydronaphthalen-1-yl 2,2-dimethylbutanoate (AM1), and 8-(3,5-dihydroxy-7-((2-(2-hydroxy)ethyl)amino)-7-oxoheptyl)-3,7-dimethyl-1,2,3,7,8,8a-hexahydronaphthalen-1-yl 2,2-dimethylbutanoate (AM2).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

RPMI 1640 medium, Keratinocyte SFM medium, DMEM medium, 2’,7’ – dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA), gentamicin, and L-glutamine were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). FBS and charcoal-treated FBS were obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA). Molecular biology-grade agarose was procured from Fisher Biotech (Fair Lawn, NJ). Docetaxel was purchased from Aventis Pharmaceutical Products Inc. (Collegeville PA). Protein molecular weight standard markers, acrylamide, and Bradford protein assay kit were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Anti-AR (#C1411, 1:400), anti-cyclin B1 (#K1907, 1:1000), anti-BclXL (#F111, 1:1000), anti-Bax (#G241, 1:1000), anti-phospho-ErbB-2 (Y1221/2) (#B2212, 1:1000), anti-ErbB-2 (#E3110, 1:1000), anti-NFĸB (#H052, 1:500), anti-p38 (#H272, 1:1000), anti-p53 (#K2607, 1:1000), anti-PCNA (#6261, 1:1000), anti-PSA (#E1812, 1:2000), anti-Survivin (#C271, 1:2000), and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse (#C2011, 1:5000), anti-rabbit (#D2910, 1:5000), anti-goat (#J0608, 1:5000) IgG Abs were all obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-phospho-AKT (Ser473) (#GA160, 1:1000), anti-AKT (#C1411, 1:2000), anti-Caspase 3 (#9665S, 1:1000), anti-PARP (#9532S, 1:1000), anti-phospho-p38 (T180/Y182) (#9211S, 1:1000), and anti-Snail (#3895S, 1:1000) Abs were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-HO-1 (#Z04608d, 1:1000) Ab was obtained from ENZO Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). Anti-Nrf2 (ab62352, 1:1000) Ab was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Anti-β-actin (#99H4842, 1:10000) and anti-NOX5 (#3116867, 1:1000) Abs, atorvastatin, DHT, propidium iodide, and simvastatin were procured from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Statin derivative compounds [simvastatin hydroxyacid] (SVA), [8-(3,5-dihydroxy-7-((2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethyl)amino)-7-oxoheptyl)-3,7-dimethyl-1,2,3,7,8,8a-hexahydronaphthalen-1-yl 2,2-dimethylbutanoate] (AM1), and [8-(3,5-dihydroxy-7-((2-(2-hydroxy)ethyl)amino)-7-oxoheptyl)-3,7-dimethyl-1,2,3,7,8,8a-hexahydronaphthalen-1-yl 2,2-dimethylbutanoate] (AM2) were provided by Dr. Chen’s laboratory, and synthesized based on the structure of simvastatin. Their structures are shown in Figure 1, and chemical abbreviations are used throughout the text.

2.2 Cell Culture

Human prostate carcinoma cell lines LNCaP, VCaP, PC-3, and DU145 cells were originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). LNCaP C-81, PC-3, DU145, and immortalized benign prostate epithelial RWPE1cells were routinely maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin [23,24]. VCaP cells were maintained in DMEM medium containing 15% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, and 10 μg/ml ciprofloxacin [24,25]. As reported previously, we established AI LNCaP C-81 cells which obtain many biochemical properties of clinical CR PCa in addition to possessing the enzymatic capacity to synthesize androgens from cholesterol. These properties include the expression of functional AR as well as PSA secretion and rapid cell proliferation in androgen-depleted conditions [11,23-27]. RWPE1 cells were cultured in Keratinocyte-SFM supplemented with bovine pituitary extract (25 μg/ml) and recombinant epidermal growth factor (0.15 ng/ml) along with 50 μg/ml gentamicin. To mimic conditions of clinical ADT, cells were maintained in SR conditions, i.e., phenol red-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% charcoal/dextran-treated FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, and 1 nM DHT. Statin derivatives simvastatin, SVA, AM1, and AM2 were dissolved in DMSO at 20 mM stock concentrations, stored at -20°C, and diluted as needed for experimental conditions in the respective medium.

2.3 Trypan Blue Proliferation Assay and Determination of Cell Membrane Permeability

For cell proliferation experiments under regular conditions, cells were seeded in regular culture medium and allowed to attach for 3 days, then changed to fresh medium containing the respective statin compounds and cultured for an additional 3 days. To determine cell proliferation under SR conditions, all cells were seeded in regular conditions and allowed to attach for 3 days. Cells were then steroid-starved for 48 hours in SR medium, and changed to fresh SR medium containing the noted compound(s) and cultured for an additional 3 days. Control groups received solvent DMSO alone. Cells were harvested via trypsinization and live cell numbers were counted by Trypan Blue dye exclusion assay using a Cellometer Auto T4 Image-based cell counter (Nexcelom, MA, USA). To determine cell membrane integrity, cells were treated as described above and a ratio of blue-stained cells to total counted cells was determined.

2.4 Clonogenic and Soft Agar Colony Formation Assays

The clonogenic cell growth assay was conducted as described previously [23,28]. Briefly, LNCaP C-81 cells were plated on the plastic surface of 6-well plates under regular culture conditions at a density of 2,000 cells per well. Cells were incubated overnight, the unattached cells were removed and remaining cells were fed with fresh regular medium containing 20 μM statin-compounds. Cells were grown for 9 days with a change of fresh medium every 3 days. On the 10th day, the medium was removed and cells were washed with ice-cold HEPES-buffered saline, then attached cells were stained with a 0.2% crystal violet solution containing 50% methanol.

The effect of statin agents on anchorage-independent LNCaP C-81 colony growth was assessed by soft agar assay. Briefly, 5 × 104 cells were seeded into a 0.25% agarose top layer with a base layer containing 0.3% agarose in 35mm dishes. The day after seeding, cell clusters containing more than one cell were excluded from the study. Cells were then fed with 0.5 mL of fresh regular medium containing the respective statin-agent every 3 days for 6 weeks. The colonies were then stained with a 0.2% crystal violet solution containing 50% methanol and counted.

2.5 Transwell Migration Assay

To determine the effect of Statin derivatives on PCa cell mobility, LNCaP C-81 cell migration was assessed via Boyden chamber assay. Cells were plated at a density of 5 × 104 cells into the upper chamber of 24-well plate transwell inserts. Medium containing 20 μM statin-compounds or solvent alone for control was placed in both upper and lower chambers of the transwells. After 24 hour incubation, cells were stained with 0.2% crystal violet solution in 50% methanol and cells remaining in the upper chamber were removed via cotton swab. Cells which had migrated through to the lower chamber were counted at 40x magnification under a microscope.

2.6 Determination of Cellular Cholesterol Level

The level of cellular cholesterol was determined using the Abcam cholesterol assay kit [29]. Briefly, LNCaP C-81 cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were treated with medium containing 20 μM statin derivatives or solvent alone for 3 days. The medium was then removed and cells were fixed for 10 minutes, followed by 3x wash with cholesterol detection buffer for 5 minutes. In the absence of light, cells were then stained with Filipin III for 1 hour and washed 2x for 5 minutes. Staining was examined via a fluorescence microscope and the relative fluorescence was quantified using Ziess-provided imaging program Zen lite 2012.

2.7 Immunoblot Analysis

All cells were rinsed with ice-cold HEPES-buffered saline, pH 7.0, harvested via scraping, and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Total cellular lysates were prepared as previously described [30,31]. The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using a Bio-Rad Bradford protein-assay. For immunoblotting, an aliquot of total cell lysate was electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (7.5%-12%). After being transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with the corresponding primary Ab overnight at 4°C. Membranes were then rinsed and incubated with the appropriate secondary Ab for 60 minutes at room temperature. Proteins of interest were detected by an ECL reagent kit and β-actin was used as a loading control. The intensity of the protein bands were analyzed with ImageJ software [30].

2.8 ROS and Cell Cycle Determination by Flow Cytometry Analysis

To determine the compounds’ effects on cell cycle, flow cytometry analysis was conducted as previously described [31]. Briefly, LNCaP C-81 cells were seeded in T25 flasks at a density of 5 × 104 cells in regular medium for 3 days, changed to SR medium for 48 hours, and then fed with fresh SR medium containing 20 μM of the specified compound. Cells were harvested after 3 days of treatment, fixed with 70% ethanol, and stained using Telford Reagent at 4°C for 4 hours [32].

Changes in cellular ROS levels induced by statin-compounds in LNCaP C-81 cells were determined via DCF-DA dye analysis [33]. Cells were plated in triplicate at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well using 6-well plastic plates and grown under regular conditions for 3 days. Cells were then steroid starved for 48 hours in SR medium before being changed to fresh SR medium containing the noted treatment compound(s) and cultured for an additional 3 days. Control groups received solvent DMSO alone. Cells were harvested and incubated with medium containing 20 μM DCF-DA dye. Determination of cell cycle distribution and DCF-DA fluorescence was carried out using the Becton-Dickinson fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) at the UNMC Flow Cytometry Core Facility.

2.9 Statistical Analysis

Each set of experiments was conducted in duplicate or triplicate as specified in the figure legend, and experiments were repeated independently at least three times. The mean and standard error values of all results were calculated and two-tailed student-t tests were used to determine significance of results. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.01 Growth Suppressive Effects of Statin Derivatives on PCa Cells

Many reports analyzing the effect of statin agents on CR PCa cells have been carried out using AR-null PCa cells lines such as PC-3 or DU145 [34]. However, most clinical CR PCa retains AR signaling; therefore in this study we used the LNCaP C-81 cell line which possesses active AR and is a more clinically useful model for CR PCa. C-81 cells were initially treated with simvastatin (Fig. 2A) or atorvastatin (data not shown) at concentrations from 0-20 μM under regular culture conditions. After 3 days of treatment, cell growth suppression was determined by live-cell counting, and both compounds were found to have similar potency with an IC50 of 8.3 μM (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis showed a similar dosage-response of PCNA protein level, a cell proliferation marker (Fig. 2B). Inhibition of cell growth by simvastatin was observed at clinically achievable micromolar concentrations.

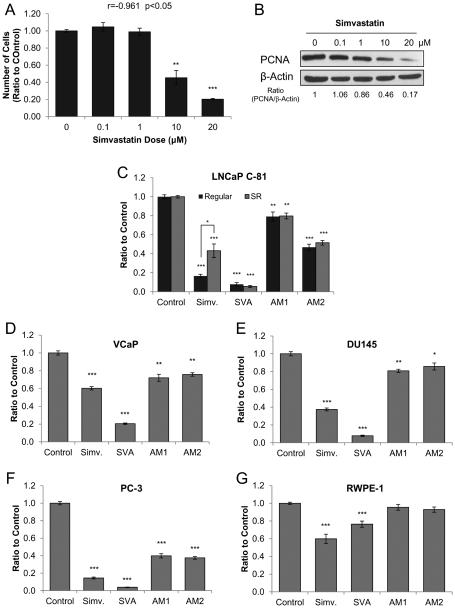

Figure 2. Effects of statin derivatives on PCa cell growth.

(A) Dosage effect of simvastatin on LNCaP C-81 cells. Cells were plated in six-well plates at 2 × 103 cells/cm2 in regular medium for attachment and grown for 72 hours. Cells were then fed with fresh medium containing 0-20 μM simvastatin with solvent alone for control and grown for an additional 72 hours. Cells were trypsinized and live cell numbers were counted by trypan blue staining. The correlative coefficient of dosage effect was r=0.906; p<0.05. The results presented are mean ± SE; n=2×2. *p<0.05.

(B) Cell lysates from (A) were collected for immunoblot analysis of PCNA. β-actin protein level was used as a loading control. Similar results were observed in two sets of independent experiments.

(C) Effects of statin derivatives on the growth of LNCaP C-81 cells. Under regular conditions, cells were plated in six-well plates at 3 × 103 cells/cm2 and maintained for 72 hours, then treated with fresh medium containing 20 μM statin-compounds for 72 hours. To mimic steroid-deprived (SR) conditions, cells were plated in six-well plates at 2 × 103 cells/cm2 and grown for 72 hours, steroid-starved for 48 hours, then fed with fresh SR medium with 1 nM DHT containing 20 μM statin-compounds and grown for 72 hours. Cells were trypsinized and live cell number was counted. Results presented are mean ± SE; n=3×3. *p<0.05; **p<0.001; ***p<0.0001.

Using the same protocol as described in (C), the effect of statin derivatives on PCa cell growth under SR conditions was determined for (D) VCaP - 1.5 × 104 cells/cm2, (E) PC-3 - 2 × 103 cells/cm2, and (F) DU145 - 2 × 103 cells/cm2, (G) RWPE-1 - 1 × 104 cells/cm2.Results presented are mean ± SE; n=3×3. *p<0.05; **p<0.001; ***p<0.0001.

In attempt to identify more potent statin derivatives, LNCaP C-81 cells were treated for three days in regular culture medium containing 20 μM of each compound: simvastatin, SVA, AM1, and AM2. Simvastatin and SVA inhibited C-81 cell growth by over 80%, while AM1 and AM2 suppressed growth by 20% and 50%, respectively (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, when C-81 cells were treated in SR medium to mimic ADT conditions, the potency of simvastatin decreased with 60% inhibition, while that of SVA, AM1, and AM2 remained unchanged (Fig. 2C). Thus, a concentration of 20 μM was found to be suitable for treatment under SR conditions used to conduct all further experiments.

The inhibitors were then tested on a panel of PCa cell lines under SR conditions including: VCaP, PC-3, and DU145 (Fig. 2D-F). SVA was the most effective, suppressing androgen-sensitive VCaP cell growth by 80%, followed by simvastatin at 40%, while AM1 and AM2 each had 20% growth inhibition (Fig. 2D) [25]. In DU145 and PC-3 cell lines, both of which are androgen-independent and lack AR expression, SVA was the most potent, followed by simvastatin, and AM1 and AM2 exhibited the least inhibitory effect on both cell lines (Fig. 2E-F). Then, to determine compound selectivity, the experiment was repeated using immortalized the benign prostate epithelial RWPE-1 cell line. All compounds were found to be less potent against RWPE-1 cells with SVA demonstrating the most selectivity (Fig. 2G). Together, the data demonstrates that SVA is the most potent and selective suppressor of both androgen-sensitive and androgen-independent cell growth under SR conditions.

3.02 Effects of Statin Derivatives on PCa Cell Tumorigenicity

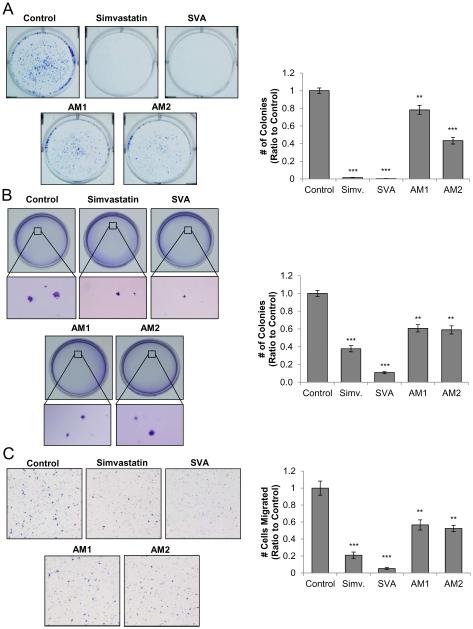

Using the LNCaP C-81 cell line as a model system, we investigated whether statin derivatives can suppress PCa tumorigenicity including cell colony formation and migration. In the clonogenic anchorage-dependent assay, LNCaP C-81 cells were treated with each compound at 20 μM for 10 days. As shown in Figure 3A, both simvastatin and SVA were potent inhibitors of colony growth on the plastic-ware surface with over 90% inhibition. Compounds AM1 and AM2 were less potent with about 20% and 55% inhibition, respectively. Colony formation in a 3-dimentional environment was evaluated using the soft agar anchorage-independent assay, in which LNCaP C-81 cells were cultured in an agarose matrix for six weeks. As seen in Figure 3B, SVA suppressed colony formation by 90%, while simvastatin reduced colony growth by 60%. AM1 and AM2 each reduced colony growth by 40%. The colony size was also decreased by SVA and simvastatin.

Figure 3. Effects of statin derivatives on CR PCa tumorigenicity.

(A) Clonogenic assay on plastic wares. LNCaP C-81 cells were plated in six-well plates at 2,000 cells/well. After 24 hours, attached cells were treated with respective compounds at 20 μM or solvent alone as control. Cells were fed on days 3, 6, and 9 with fresh culture media containing respective statin derivatives. On day 10, representative photos of colony plates were taken and the number of colonies counted. Results presented are mean ± SE; n=3×3. **p<0.005 ***p<0.0005.

(B) Anchorage-independent soft agar assay. LNCaP C-81 cells were plated at a density of 5 × 104 cells/35mm dish in 0.25% soft agarose with a base layer of 0.3% agarose. After 24 hours, cells in doublets or greater were marked and excluded from the study. Culture medium containing respective compounds at 20 μM or solvent alone was added every 72 hours, and after 6 weeks, colonies were stained and fixed. Representative images of colonies were taken and the number of colonies counted. Results presented are mean ± SE; n=3×3. **p<0.005 *** p<0.0001.

(C). Cell migration transwell assay. Cell migration was assessed via Boyden chamber assay. 6 × 104 C-81 cells were seeded in the transwell insert of 24-well plates. Medium containing 20 μM of respective compounds or solvent alone for control were placed in the lower chamber. After 24-hour incubation, the migrated cells were stained and those cells remaining in the upper chamber were removed via cotton swab and cells which had migrated through to the lower chamber were counted. Representative images are shown at 40x magnification. Results presented are mean ± SE; n=3×3. **p<0.005 ***p<0.0005.

The Boyden Chamber transwell migration assay was used to investigate the effect of these compounds on PCa cell migratory potential. SVA inhibited migration by over 90%, closely followed by simvastatin at 80%. AM1 and AM2 had similar effects with 40% and 45% inhibition, respectively (Fig. 3C). Collectively, compound SVA exhibited the most potent inhibitory activity on PCa cell tumorigenicity.

3.03 Suppression of Cholesterol Synthesis by Statin Derivatives

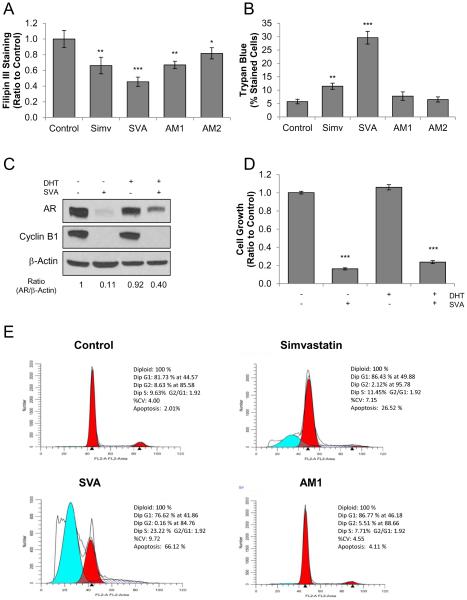

Clinically, statin derivatives, such as simvastatin, are primarily prescribed to reduce patients’ circulating cholesterol levels. To examine their ability to reduce cholesterol in PCa cells, statin compound-treated LNCaP C-81 cells were stained with Filipin III for cholesterol detection and the fluorescence was semi-quantified via confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 4A, while all compounds significantly reduced cellular cholesterol levels, SVA was the most effective with a 50% reduction of cholesterol level in treated cells. Unexpectedly, simvastatin and AM1 had a similar 35% reduction in cholesterol level, while AM2 was least effective with only 20% inhibition.

Figure 4. Mechanism of statin-derivative suppression of CR PCa tumorigenicity.

(A) Statin derivative’s inhibition of LNCaP C-81 cholesterol synthesis. Cells were plated in 96- well plates at 2 × 103 cells/cm per well in regular medium and allowed to attach over-night then fed with fresh medium containing 20 μM statin derivatives and grown for 72 hours. Cells were stained with Filipin III and examined via fluorescence microscopy. The results presented are mean ± SE; n=5×3. *p<0.05 **p<0.005 ***p<0.0005.

(B) Effects of statin derivatives on cell membrane integrity in LNCaP C-81 cells. Under regular conditions, cells were plated in six-well plates at 3 × 103 cells/cm2 and maintained for 72 hours, then steroid-starved for 48 hours. After, cells were fed with fresh SR medium with 1 nM DHT containing 20 μM statin derivatives and grown for 72 hours. Cells were trypsinized and strained with Trypan Blue dye and the ratio of blue to total cells counted was recorded. The results presented are mean ± SE; n=3×3. **p<0.005 ***p<0.0005.

(C) Effect of SVA on AR. LNCaP C-81 cells were treated with 20 μM SVA, 10 nM DHT, or both for 72 hours under SR conditions. Total cell lysate proteins were collected for immunoblot analysis of AR and Cyclin B1 protein levels. β-actin protein level was used as a loading control. Similar results were observed in two sets of independent experiments.

(D) LNCaP C-81 cells were treated with 20 μM SVA, 10 nM DHT, or both for 72 hours under SR conditions. Cells were trypsinized and live cell numbers were counted. The results presented are mean ± SE; n=3×3. ***p<0.0005.

(E) Histograms of cell cycle distributions of statin-treated LNCaP C-81 cells. Cells were plated in T25 flasks at 5 × 103 cells/cm2 in regular medium and maintained for 72 hours, then steroid- starved for 48 hours, followed by treatment with 20 μM of respective compounds in SR medium for 72 hours. Cells were harvested using trypsin, stained with propidium iodide, and cell-cycle was analyzed via flow cytometric analysis. One set of representative data is shown. Similar results were obtained from three sets of independent experiments.

3.04 Influence of Statin Derivatives on PCa Cell Membrane Integrity

Cholesterol is an integral component of cell membrane stability and fluidity and is highly enriched in lipid rafts which anchor many proteins vital to cell signaling. Therefore, decreased cholesterol levels are expected to destabilize the cell membrane and alter cell signaling. We determined the impact of these compounds on membrane integrity by Trypan Blue dye-exclusion assay. As shown in Figure 4B, SVA induced membrane damage in 30% of treated cells and simvastatin disrupted membranes in 12% of cells, while compounds AM1 and AM2 had no significant impact on membrane permeability. The data together indicates these compounds suppress tumor cells, in part, by reducing cholesterol levels (Fig. 4A) and disrupting cell membranes (Fig. 4B).

3.05 SVA Inhibition of Androgen Receptor

Due to the importance of AR function in CR PCa, the effect of SVA on AR was evaluated in LNCaP C-81 cells. Cells were grown in SR medium with or without 10 nM DHT, treated with SVA for 3 days, and whole cell lysates were analyzed via western blot. As shown in Figure 4C, under androgen-deprived conditions, SVA functioned as a potent suppressor of AR protein level. However, in the presence of 10 nM DHT, AR was partially protected from SVA blockage. SVA strongly reduced growth-regulator Cyclin B1 protein, independent of the presence of androgens [29]. In parallel, cell growth was greatly suppressed by SVA regardless of the presence of androgens and correlates with Cyclin B1 protein levels (Fig. 4D). Thus, SVA effectively inhibits Cyclin B1, a positive cell cycle regulator, and cell proliferation independent of androgen availability.

3.06 Effect of Statin Derivatives on PCa Cell Cycle

To further investigate the mechanism through which statin derivatives inhibit PCa cell tumorigenicity, we focused our efforts on comparing SVA and AM1 with simvastatin and performed cell cycle analysis on statin-treated LNCaP C-81 cells. Flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 4E) revealed the percentage of apoptotic cells rose sharply under SVA and simvastatin treatments to 66% and 27%, respectively, compared to that of only 2% of control and 4% of AM1-treated cells. In addition, SVA and simvastatin treatments greatly increased the percentage of cells in S phase accompanied with a decreased percentage of cells in G2 phase. Thus, SVA and simvastatin induce apoptosis as well as cell cycle arrest in S phase.

3.07 Effect of Statin Derivatives on Cell Signaling Under SR Conditions

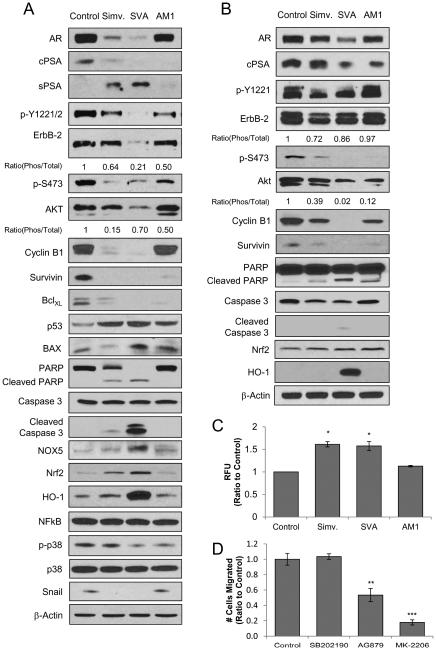

To investigate the mechanism through which the statin derivatives inhibit PCa tumorigenicity under SR conditions, we analyzed their effects on key signaling molecules known to contribute to PCa progression using LNCaP C-81 cells. AR is a major target of anti-PCa agents and remains a vital signaling pathway even in CR PCa cells [27,28]. While all compounds decreased AR protein in C-81 cells, SVA was the most potent followed by simvastatin, and AM1 had only marginal effect (Fig. 5A). This correlates with reduced cellular prostate-specific antigen (cPSA) with the exception of AM1 treatment. Interestingly, secreted prostate specific antigen (sPSA) protein level was increased by simvastatin and SVA. In addition, ErbB-2 is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase which regulates AKT and can be activated by androgen signaling in PCa through phosphorylation at Y1221/2 [20-22,30]. Upon treatment with statin derivatives, all agents reduced ErbB-2 Y1221/2 phosphorylation with SVA having the greatest effect. SVA also reduced the total ErbB-2 protein while other compounds had a limited impact (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, while all statin derivatives inhibited AKT phosphorylation at S473, SVA also effectively reduced total AKT protein levels.

Figure 5. Molecular profiling of LNCaP C-81 signaling upon statin-derivative treatment under SR conditions.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of statin-treated LNCaP C-81 cells. Cells were plated in T25 flasks at 5 × 103 cells/cm2 in regular medium, maintained for 72 hours, then steroid starved for 48 hours. Cells were treated with 20 μM of respective compounds and grown for an additional 72 hours under SR conditions. Cells were trypsinized and total cell lysate proteins were collected. Total cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylated ErbB-2, AKT, and p38 by site-specific phospho- Abs as well as total AR, cPSA, sPSA, ErbB-2, AKT, Cyclin B1, Survivin, BclXL, p53, BAX, PARP, Caspase 3, NOX5, Nrf2, HO-1, NFĸB, p38, and Snail protein levels. β-actin protein level was used as a loading control. Similar results were observed in three sets of independent experiments.

(B) Immunoblot analysis of statin-treated VCaP cells. Cells were plated in T75 flasks at 1.3 × 104 cells/cm2 in regular medium, maintained for 72 hours, then steroid starved for 48 hours. Cells were treated with 20 μM of respective compounds and grown for an additional 72 hours under SR conditions. Cells were trypsinized and total cell lysate proteins were collected. Total cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylated ErbB-2 and AKT by site-specific phospho-Abs as well as total AR, cPSA, ErbB-2, AKT, Cyclin B1, Survivin, PARP, Caspase 3, Nrf2 and HO-1 protein levels. β-actin protein level was used as a loading control. Similar results were observed in three sets of independent experiments.

(C) Analysis of ROS with DCF-DA dye in statin-treated LNCaP C-81 cells. Cells were plated in T25 flasks at 1 × 104 cells/cm2 and maintained for 72 hours, then steroid-starved for 48 hours, followed by treatment with 20 μM of respective compounds in fresh SR medium for 72 hours. Cells were then incubated with 20 μM DCF-DA for 30 minutes before being harvested and analyzed via flow cytometry. Results presented are mean ± SE; n=3. *p<0.05.

(D). Transwell assay with LNCaP C-81 cells treated with small-molecule inhibitors. Cell migration was assessed via Boyden chamber assay. 6 × 104 C-81 cells were seeded in the transwell insert of 24-well plates. Medium containing small-molecule inhibitors 10 μM SB202190 (p38), 1 μM AG879 (ErbB-2), or 10 μM MK2206 (AKT) was placed in the lower chamber. After 24-hour incubation, the migrated cells were fixed and stained. Cells remaining in the upper chamber were removed via cotton swab and cells which had migrated through to the lower chamber were counted. Results presented are mean ± SE; n=3×3. **p<0.005 ***p<0.0005.

Downstream targets of AKT include Survivin and p53, while both AKT and AR can regulate Cyclin B1 [33,35]. AKT upregulates Survivin, an anti-apoptotic protein, and upon treatment, all compounds greatly reduced Survivin protein levels (Fig. 5A). Cyclin B1, a cell growth regulator, was strongly inhibited by simvastatin and SVA, but not AM1. Furthermore, p53 is an inducer of apoptosis and is suppressed by AKT; p53 was elevated upon statin compound treatment and its downstream target BAX, another pro-apoptotic protein [36], was elevated only by SVA. Conversely, anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL protein levels were greatly reduced by all statin compounds (Fig. 5A). Elevated levels of cleaved PARP and Caspase 3 were also observed in treated cells with SVA having the greatest effect, providing further evidence of induced apoptosis. Together, upon statin compound treatment there is an overall trend of proliferative and anti-apoptotic protein inhibition, while pro-apoptotic proteins were induced.

We investigated whether oxidative stress is involved in statin-induced tumor suppression. Indeed, as shown in Figure 5A, NOX5 protein, which functions to generate superoxide at the cell membrane, was greatly increased by SVA treatment. Moreover, while no observable change was found in redox-sensitive NF-ĸB protein, ROS-response protein Nrf2 and its downstream target HO-1 were highly induced by SVA and to a lesser extent by simvastatin. This may indicate simvastatin and SVA promote oxidative stress resulting in activation of apoptotic pathways.

Statin derivatives also inhibit PCa cell migration (Fig. 3C). Since AKT is associated with motility, we analyzed the level of Snail protein, a downstream target of AKT, as well as activation of p38, both of which are associated with cell migration and stress-response [37,38]. Snail was suppressed by both simvastatin and SVA and correlated with inhibition of AKT activation. Phosphorylation and activation of p38 was inhibited by SVA and AM1, but not by simvastatin (Fig. 5A).

To further validate the compounds’ effect on PCa signaling, primary target molecules were also investigated using VCaP cells shown in Figure 5B. A similar trend in AR, cPSA, Cyclin B1, Survivin, PARP, Caspase 3, Nrf2, and HO-1 protein levels were observed compared to C-81 treated cells with SVA having the greatest suppressive effect. Interestingly, simvastatin had greater inhibitory effect on total and phosphorylated ErbB-2 than SVA. In addition, while SVA was again the most potent inhibitor of total and phosphorylated AKT, AM1 had a greater inhibitory effect than simvastatin. Overall, a similar trend in inhibition of key functional proteins was observed in both VCaP and LNCaP C-81 cell lines.

3.08 DCF-DA Dye Analysis of LNCaP C-81 Cells Treated with Statin Derivatives

Upon observing an increase of NOX5 protein level as well as ROS-response proteins Nrf2 and HO-1 in statin-treated LNCaP C-81 cells, we investigated the effect of these compounds on ROS generation. This was semi-quantified by DCF-DA dye and fluorescence was measured via flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 5C, both simvastatin and SVA significantly increased cellular levels of ROS, while AM1 had no significant effect. This data demonstrates simvastatin and SVA induce ROS generation, causing oxidative stress in PCa cells under SR conditions which can contribute to growth suppression and apoptosis.

3.09 LNCaP C-81 Migration in the Presence of Small Molecule Inhibitors

Statin compounds inhibit PCa cell migration (Fig. 3C) as well as AKT and p38 pathways (Fig. 5A) which are both associated with cell motility. To determine which of these signaling pathways regulate LNCaP C-81 cell migration, transwell assays were conducted with small molecule inhibitors of p38 (SB202190), AKT (MK-2206), and ErbB-2 (AG879) [39-41]. As shown in Figure 5D, inhibition of p38 had no impact on C-81 cell migration; inhibition of ErbB-2 reduced migration by 50%, and inhibition of AKT suppressed migration by over 80%. The results indicate statin compounds inhibit of PCa cell migration primarily through suppression of the ErbB-2/AKT signaling pathway.

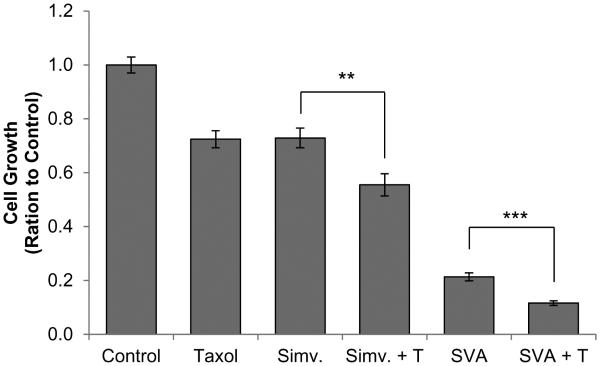

3.10 Growth Suppression via Combined Docetaxel and Statin-Derivative Treatment

Simvastatin has previously been reported to have an added inhibitory effect on PCa cell growth when combined with docetaxel treatment [42]. To determine the interaction between SVA and docetaxel, the compounds were used to treat C-81 cells under SR conditions independently and in combination, and cell growth was determined. Both simvastatin and SVA (5 μM each) were found to possess an added effect on cell growth suppression when combined with docetaxel (1 nM).

4. Discussion

CR PCa remains an incurable disease and an effective therapy is immediately needed. Recent in vitro and epidemiological studies revealed that inhibition of cholesterol synthesis by statin derivatives may be an effective treatment strategy for CR PCa [11-16,43]. In the present study utilizing clinically-relevant PCa cell line models, we show for the first time that novel statin derivatives are effective suppressors of CR PCa tumorigenicity through inhibition of both AR and AKT pathways as well as induction of apoptosis. These compounds have the potential to serve as effective therapeutic agents for CR PCa.

In addition to template-compound simvastatin, we investigated the ability of novel statin derivatives SVA, AM1, and AM2 to suppress CR PCa proliferation. We chose LNCaP C-81 cells as our primary experimental model due to their steroidogenic ability to synthesize androgens from cholesterol in addition to the possession of many biochemical properties common to clinical CR PCa [11,20-22]. While simvastatin is a less potent inhibitor of C-81 cell proliferation under SR conditions compared to regular steroid conditions, the potency of SVA, AM1, and AM2 remains unaltered. This may indicate steroid-deprivation reduces the cells’ ability to activate simvastatin, while SVA, AM1, and AM2 are in active states. Moreover, SVA is the most potent inhibitor of cell growth in all cell lines examined. Notably, the compounds are effective inhibitors of AR-negative DU145 and PC-3 cell growth, which indicates statin derivatives suppress cell proliferation through alternative mechanisms in addition to inhibition of AR signaling. The compounds were also found to have selective inhibition, with all compounds demonstrating reduced potency against benign epithelial RWPE-1 cells as shown in Figure 2G. Furthermore, these compounds suppress tumorigenicity including colony formation and migration. Among them, SVA exhibits the most potent suppression of PCa tumor phenotype followed by simvastatin, while AM1 and AM2 had the least effect.

We determined whether these compounds have an impact on AR signaling to test our hypothesis that depriving C-81 cells of cholesterol blocks their ability to synthesize androgen and thus inhibits AR pathways. Statin derivatives were found to reduce AR protein level correlating with a decrease in cellular PSA, despite an increase in secreted PSA. This rise in secreted PSA may be attributed to the loss of membrane stability, allowing PSA protein to leak out of the cell. Moreover, SVA is a potent inhibitor of AR in C-81 cells under SR conditions; however, in the presence of DHT, the impact on AR protein level is reduced (Fig. 4C). Unexpectedly, SVA suppression of cell proliferation is only marginally reduced in the presence of androgens, while its impact on AR protein level is greatly diminished (Figs. 2C, 4D). This data correlates with observed statin inhibition of AR-null PC-3 and DU145 proliferation (Figs. 2E-F) and thus supports the notion that cell growth is suppressed by other mechanisms in addition to AR signaling.

PCa cells possess enriched cholesterol and lipid raft concentrations in comparison to benign cells, and simvastatin has been reported to reduce both lipid raft and cell cholesterol levels in prostate cells [43,44]. The observations in those reports correlate with our data showing a reduction in cellular cholesterol and destabilization of C-81 cell membranes upon statin compound treatment (Fig. 4A, 4B). Additionally, the compounds’ selective growth inhibition may be attributed to the fact that PCa cells undergo rapid proliferation and more dynamic membrane activity compared to benign cells. Moreover, Adam et al. [45] demonstrated that a cholesterol-sensitive subgroup of AKT, which enhances tumor cell survival and metastatic ability, is enriched in PCa cells and is dependent upon lipid raft availability for activation via phosphorylation. In parallel, a correlation has been reported between decreased AKT activation and prevention of lipid raft formation as a result of simvastatin’s inhibition of cholesterol synthesis [44]. Indeed, our data clearly demonstrates AKT activation is inhibited by statin compounds (Fig. 5A, 5B) and correlates with loss of membrane integrity (Fig. 4B). Collectively, inhibition of AKT signaling is a major mechanism of statin-mediated suppression of PCa cell tumorigenicity.

Inhibition of AKT may be achieved via suppression of ErbB-2, a hyper-phosphorylated and activated transmembrane tyrosine kinase in CR PCa cells which can upregulate AKT by promoting activation via S473 phosphorylation [30, 32]. Emerging studies reveal, in addition to AR, AKT signaling is vital to the progression and development of CR PCa [46,47]. Our data shows statin derivatives inhibit AKT activation as well as reduces total AKT protein levels, correlating with ErbB-2 status and their effect on tumor phenotype (Fig 5A, 5B). We propose disruption of the cell membrane can reduce ErbB-2 stability resulting in prevention of AKT activation. Alternatively, we cannot rule-out the possibility that statin-agents directly interact with and inhibit ErbB-2 and/or AKT. These changes in signaling correlate with a large increase of apoptosis and induction of S-phase cell cycle arrest (Fig. 4E). Together, the data indicates statin compounds suppress cell survival signaling and induce cell death while SVA has the most potent effect.

Upon observing an elevation of pro-apoptotic proteins and a decrease in survival-associated proteins after statin treatment, we investigated the impact of statin compounds on cellular ROS production and induction of oxidative stress. In Figure 5C, a significant increase in cellular ROS is shown in cells treated with simvastatin and SVA. Superoxide generating protein, NOX5, was found to be increased upon treatment with statin derivatives, which may contribute to the elevated ROS level. However further investigation is required to determine the exact mechanism of its involvement [48]. We also observed a rise in ROS-response proteins Nrf2 and its downstream target HO-1 which induces antioxidant mechanisms within the cell (Fig. 5A, 5B) [49]. While the total protein levels of NFĸB, another ROS-sensitive protein, were not altered upon statin-compound treatment, changes in its subcellular localization may occur and requires further study. Collectively, our data shows statin derivatives induce cellular stress in part by increasing ROS which correlates with elevated apoptosis.

In addition to inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis, statin derivatives also reduce cell migratory ability (Fig. 3C). Western blot analysis (Fig. 5A) revealed the inhibition of a number of motility-related proteins. Moreover, AKT and its downstream target Snail both are strongly inhibited by simvastatin and SVA. While p38 is often associated with cell migration and has decreased activation under SVA and AM1 treatment (Fig. 5A), its inactivation by statins does not correlate with migratory activity (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, as shown in Figure 5D, p38 inhibition has no impact on C-81 motility. In comparison, ErbB-2 inhibition impedes migration by about 40% and AKT inhibition reduces migration by over 80%. The data together indicates statin derivatives reduce the PCa cell migratory ability and tumorigenicity, in part, through inhibition of the AKT pathway.

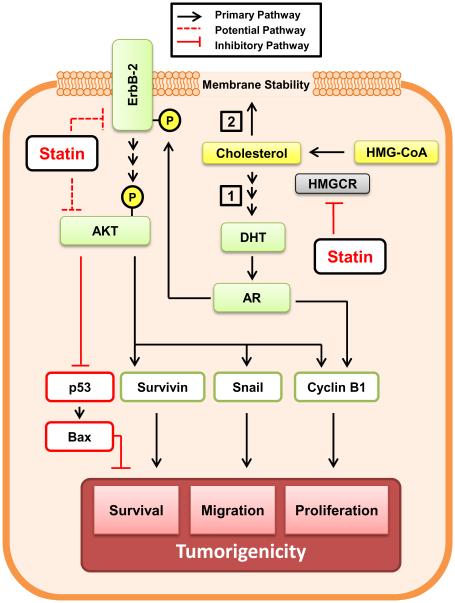

In summary, our study uses the clinically relevant LNCaP C-81 cell line model to demonstrate the novel compound SVA is a potent antagonist of CR PCa tumorigenicity and functions to suppress tumor phenotype through concurrent inhibition of AR and AKT pathways. As depicted in Figure 7, statin derivatives suppress tumor progression in two ways: first, these compounds inhibit androgen biosynthesis from cholesterol in CR PCa cells which obtain intracrine regulation [11]. In addition, the lack of cholesterol reduces the cell membrane’s integrity which is necessary for ErbB-2 and downstream AKT function. It is also possible the statins physically interact with and suppress AKT. While both AR and AKT signaling contribute to PCa cell tumor phenotype including proliferation and migration, our data indicates inhibition of the AKT pathway is the primary mechanism by which statin agents mediate tumor suppression. Importantly, aberrant AKT signaling is prevalent in a major subpopulation of advanced prostate tumors which endows statin derivatives with broad therapeutic potential. Moreover, statin derivatives are well-tolerated by patients and SVA was found to have an added effect when combined with docetaxel treatment (Fig. 6). This implies SVA can be used to supplement docetaxel, which possess more severe side effects, in order to improve patient quality of life. Future studies are required to elucidate the mechanism through which statin derivatives induce oxidative stress and arrest cell cycle in S phase. Further in vivo investigation of SVA will help determine its potential as a therapeutic agent.

Figure 7. Proposed inhibitory mechanism of statin-derivatives on CR PCa cell tumorigenicity.

We propose that statin derivatives suppress CR PCa tumorigenicity through two different mechanisms. (1) First, cholesterol is required for de novo androgen synthesis and subsequent intracrine activation of androgen receptor (AR) in CR PCa cells. Activated AR can induce ErbB-2 phosphorylation and activation as well as cell cycle progression in part via up- regulation of Cyclin B1. (2) In parallel, cholesterol is vital to the cell membrane’s integrity and formation of lipid rafts; their disruption destabilizes the cell membrane as well as ErbB-2 and AKT. Moreover, inhibition of AKT leads to induction of apoptosis through activation of pro- apoptotic p53 and BAX and suppression of pro-survival protein Survivin as well as Cyclin B1. Statin-induced AKT inhibition also leads to suppression of cell migration, in part mediated through Snail. Nevertheless, direct interaction between statin agents and ErbB-2 or AKT is possible. Thus through concurrent inhibition of both AR and AKT signaling pathways in addition to plasma membrane destabilization, statin derivatives induce apoptosis and suppress CR PCa tumorigenicity.

Figure 6. Combination treatment of LNCaP C-81 cells with statin-derivatives and docetaxel.

Under regular conditions cells were plated in six-well plates at 2 × 103 cells/cm2 and grown for 72 hours, then steroid-starved for 48 hours. Cells were then fed with fresh SR medium with 1 nM DHT containing 5 μM statin derivatives, 1 nM docetaxel, or both and grown for 72 hours. Solvent DMSO alone was used for control. Cells were trypsinized and live cell numbers were counted. The results presented are mean ± SE; n=2×3. **p<0.005 ***p<0.0005.

Highlights.

Novel simvastatin derivatives SVA, AM1, and AM2 suppress CR PCa cells.

Use of clinically-relevant CR PCa LNCaP C-81 cell line model.

SVA demonstrates superior potency and effectively inhibits a panel of CR PCa cells.

Statin derivatives exhibit concurrent inhibition of AR and AKT pathways.

SVA possesses an added effect when combined with docetaxel.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Victoria Smith and Ms. Samantha Wall of the University of Nebraska Medical Center Flow Cytometry Core facility for their assistance in acquiring flow cytometry data as well as Mrs. Fen-Fen Lin, Jordan Ingersoll, and Dr. Sakthival Muniyan for procurement of preliminary data. We thank Dr. Richard G. MacDonald for providing PARP and Caspase 3 antibodies. We also appreciate assistance from Kaohsiung Medical University Center for Resources and Research and Development. This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Health [CA88184], Department of Defense [PC121645 and PC141559], as well as the University of Nebraska Medical Center Bridge Fund and Graduate Studies Fellowship. Additional funding was provided by from following grants: MOST104-2113-M-037-003, KMU-TP104B04, and NSYSUKMU103-I008-1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- Ab

- antibody

- ADT

- androgen deprivation therapy

- AI

- androgen-independent

- AR

- androgen receptor

- AS

- androgen-sensitive

- CR PCa

- castration-resistant prostate cancer

- DHT

- 5α-dihydrotestosterone

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- ECL

- enhanced chemiluminescence

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- HMGCoA

- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A

- HO-1

- Hemeoxygenase-1

- PCa

- prostate cancer

- PSA

- prostate-specific antigen

- SR

- steroid-reduced

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saad F, Hotte SJ. Guidelines for the management of castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2010;4:380–384. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.10167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asmane I, Céraline J, Duclos B, Rob L, Litique V, Barthélémy P, et al. New strategies for medical management of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncology. 2011;80:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000323495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cookson MS, Roth BJ, Dahm P, Engstrom C, Freedland SJ, Hussain M, et al. Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: AUA Guideline. J. Urol. 2013;190:429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smalet O, Scher HI, Small EJ, Verbel DA, McMillan A, Regan K, et al. Nomogram for overall survival of patients with progressive metastatic prostate cancer after castration. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:3972–3982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Culig Z, Bartsch G. Androgen axis in prostate cancer. J. Cell Biochem. 2006;99:373–381. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohler JL, Gregory CW, Ford OH, III, Kim D, Weaver CM, Petrusz P, et al. The androgen axis in recurrent prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:440–448. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1146-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han G, Buchanan G, Ittmann M, Harris JM, Yu X, Demayo FJ, et al. Mutation of the androgen receptor causes oncogenic transformation of the prostate. Proc. Natl. AcadSci. USA. 2005;102:1151–1156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408925102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh P, Uzgare A, Litvinov I, Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT. Combinatorial androgen receptor targeted therapy for prostate cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2006;13:653–666. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Titus MA, Schell MJ, Lih FB, Tomer KB, Mohler JL. Testosterone and dihydrotestosterone tissue levels in recurrent prostate cancer. Hum. Cancer Biol. 2005;11:4653–4657. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillard PR, Lin MF, Khan SA. Androgen-independent prostate cancer cells acquire the complete steroidogenic potential of synthesizing testosterone from cholesterol. Mol. Cell Endocr. 2008;295:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan KK, Oza AM, Siu LL. The statins as anticancer agents. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;9:10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon JA, Midha A, Sxeitz A, Ghaffari M, Adomat HH, Guo Y, et al. Oral simvastatin administration delays castration-resistant progression and reduces intratumoral steroidogenesis of LNCaP prostate cancer xenografts. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016;19:21–27. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2015.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geybels MS, Wright JL, Holt SK, Kolb S, Feng Z, Stanford JL. Statin use in relation to prostate cancer and high-grade prostate cancer: results from the REDUCE study. Prostate. 2013;73:1214–1222. doi: 10.1002/pros.22671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bansal D, Undela K, D’Cruz A, Schifano F. Statin use and risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046691. doi: 10.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park HS, Schoenfeld JD, Mailhot RB, Shive M, Hartman RI, Ogembo R, et al. Statins and prostate cancer recurrence following radical prostectomy or radiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2013;24:1427–1434. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, Bhala N, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomized trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergman LB, Lindh JD, Bergman P. What is a relevant statin concentration in cell experiments claiming pleiotropic effects? Brit. J of Clin. Pharm. 2011;72:164–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03907.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh KC, Kao CL, Feng CW, Wen ZH, Chang HF, Chuang SC, et al. A novel anabolic agent: a simvastatin analogue without HMG-CoA reductase inhibitory activity. Org. Lett. 2014;16:4376–4379. doi: 10.1021/ol501486b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Igawa T, Lin FF, Lee MS, Karan D, Batra SK, Lin MF. Establishment and characterization of androgen-independent human prostate cancer LNCaP cell model. Prostate. 2002;50:222–235. doi: 10.1002/pros.10054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng TC, Lin MF. Tyrosine phosphorylation of c-ErbB-2 is regulated by the cellular form of prostatic acid phosphatase in human prostate cancer cells. J. of Biol. Chem. 1998;273:22096–22104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.22096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin MF, Lee MS, Zhou ZW, Andressen JC, Meng TC, Johanzzon SL, et al. Decreased expression of cellular prostatic acid phosphatase increases tumorigenicity of human prostate cancer cells. J. of Urol. 2001;166:1943–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korenchuck S, Lehr JE, Mclearn L, Lee YG, Whitney S, Vessella R, et al. VCaP, a cell-based model system of human prostate cancer. In Vivo. 2001;12:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tai S, Sun Y, Squires JM, Zhang H, Oh WK, Liand CZ, et al. PC3 is a cell line characteristic of prostatic small cell carcinoma. Prostate. 2011;71:1668–1679. doi: 10.1002/pros.21383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scaccianoce E, Festuccia D, Dondi D, Guerini V, Bologna M, Motta M, et al. Characterization of prostate cancer DU145 cells expressing the recombinant androgen receptor. Oncol. Res. 2003;14:101–112. doi: 10.3727/000000003108748658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tilley WD, Wilson CM, Marcelli M, McPaul MJ. Androgen receptor gene expression in human prostate carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1990;50:5382–5386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Debes JD, Tindall DJ. Mechanisms of androgen refractory prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:1488–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfe AR, Atkinson RL, Reddy JP, Debeb BG, Larson R, Li L, et al. High-density and very-low-density lipoprotein have opposing roles in regulating tumor-initiating cells and sensitivity to radiation in inflammatory breast cancer. Int. J. Rad. Oncol. Biol. Physics. 2015;91:1072–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chuang TD, Chen SJ, Lin FF, Veeramani S, Kumar S, Batra SK, et al. Human prostatic acid phosphatase, an authentic tyrosine phosphatase, dephorphorylates ErbB-2 and regulates prostate cancer cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:23598–23606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.098301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingersoll MA, Lyons AS, Muniyan A, D’Cunha N, Robinson T, Hoelting K, et al. Novel imidazopyridine derivatives possess anti-tumor effect on human castration-resistant prostate cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0131811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131811. doi: 10.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhodes N, Heerding DA, Duckett DR, Eberwein DJ, Knick VB, Langsing TJ, et al. Characterization of an Akt kinase inhibitor with potent pharmacodynamic and antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2366–2374. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allan LA, Clark PR. Phosphorylation of caspase-9 by CDK1/Cyclin B1 protects mitotic cells Against apoptosis. Molec. Cell. 2007;26:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoque A, Chen H, Xu XC. Statin induces apoptosis and cell growth arrest in prostate cancer cells. J. Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:88. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0531. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernandez JG, Rodriguez DA, Valenzuela M, Calderon C, Urzua U, Munroe D, et al. Survivin expression promotes VEGF-induced tumor angiogenesis via PI3K/AKT enhanced β-catenin/Tcf-Lef dependent transcription. Mol. Cancer. 2014;13:209. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-209. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-13-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oltvai ZN, Milliman L, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 1993;74:609–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90509-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith BN, Odero-Marah VA. The role of Snail in prostate cancer. Cell Adh. Migr. 2012;6:433–441. doi: 10.4161/cam.21687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jilg CA, Ketscher A, Metzger E, Hummel B, Willmann D, Russeler V, et al. PRK1/PKN1 controls migration and metastasis of androgen-independent prostate cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2014;5:12646–12664. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manthey DL, Wang SK, Kinney SD, Yao Z. SB202190, a selective inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, is a powerful regulator of LPS-induced mRNAs in monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1998;64:409–417. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dieter MZ, Freshwater SL, Solis WA, Nebert DW, Dalton TP. Trypostin AG879, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor: prevention of transcriptional activation of electrophile and the aromatic hydrocarbon response elements. Bioc. Pharm. 2001;61:215–225. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirai H, Sootome H, Nakatsuru Y, Miyama K, Taguchi S, Tsujioka K, et al. MK-2206, an allosteric Akt inhibitor, enhances anti-tumor efficacy by standard chemotherapeutic agents of molecular targeted drugs In vitro and In vivo. Mol. Cancer Therap. 2010 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1012. doi:10.1158/1535-7163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goc A, Kochuparambil ST, Al-Husein B, Al-Azayzih A, Mohammad S, Somanath PR. Simultaneous modulation of the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways by simvastatin in mediating prostate cancer cell apoptosis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:409. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-409. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-12-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li YC, Park MJ, Ye SK, Kim CW, Kim YN. Elevated levels of cholesterol-rich lipid rafts in cancer cells are correlated with apoptosis sensitivity induced by cholesterol-depleting agents. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;168:1107–1118. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee EJ, Yun UJ, Koo KH, Sung JY, Shim J, Ye SK, et al. Down-regulation of lipid raft-associated onco-proteins via cholesterol-dependent lipid raft internalization in docosahexaenoic acid-induced apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1841:190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adam RM, Mukhopadhyay NK, Kim J, Vizio DD, Cinar B, Boucher K, et al. Cholesterol sensitivity of endogenous and myristoylated Akt. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6238–4626. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toren P, Zoubeidi A. Targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway in prostate cancer: challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Oncol. 2014;45:1793–1801. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bitting RL, Armstrong AJ. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2013;20:83–99. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fulton DJR. Nox5 and the regulation of cellular function. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:2443–2452. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khandrika L, Kumar B, Koul S, Maroni P, Koul HK. Role of oxidative stress in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2009;282:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]