Abstract

Background

Although an association between adolescent sleep and substance use is supported by the literature, few studies have characterized the longitudinal relationship between early adolescent sleep and subsequent substance use. The current study examined the prospective association between the duration and quality of sleep at age 11 and alcohol and cannabis use throughout adolescence.

Methods

The present study, drawn from a cohort of 310 boys taking part in a longitudinal study in Western Pennsylvania, includes 186 boys whose mothers completed the Child Sleep Questionnaire; sleep duration and quality at age 11 were calculated based on these reports. At ages 20 and 22, participants were interviewed regarding lifetime alcohol and cannabis use. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to determine the association between sleep and substance use.

Results

After accounting for race, socioeconomic status, neighborhood danger, active distraction, internalizing problems, and externalizing problems, both the duration and quality of sleep at age 11 were associated with multiple earlier substance use outcomes. Specifically, less sleep was associated with earlier use, intoxication, and repeated use of both alcohol and cannabis. Lower sleep quality was associated with earlier alcohol use, intoxication, and repeated use. Additionally, lower sleep quality was associated with earlier cannabis intoxication and repeated use, but not first use.

Conclusions

Both sleep duration and sleep quality in early adolescence may have implications for the development of alcohol and cannabis use throughout adolescence. Further studies to understand the mechanisms linking sleep and substance use are warranted.

Keywords: Alcohol, cannabis, sleep, adolescence

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite efforts to curb adolescent substance use, alcohol use remains high and cannabis use has been increasing (Johnston et al., 2014), suggesting work is needed to understand the risk factors underlying substance use during this unique developmental period. Many risk factors are well described, including internalizing and externalizing problems (Bongers et al., 2003), self-regulation (Wills et al., 1995), and reward regulation (Steinberg, 2007). Sleep, associated with all of these factors (Gregory and O’Connor, 2002; Hasler et al., 2012a; Killgore et al., 2006; Pesonen et al., 2010), changes dramatically in adolescence, with restriction, insomnia, and delayed timing being particularly prominent (Carskadon et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2006). Yet despite evidence linking multiple sleep constructs to adolescent substance use (Bootzin and Stevens, 2005; Hasler et al., 2012b; McKnight-Eily et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2015), adolescent sleep disturbance remains under-explored.

Sleep disturbance repeatedly has been linked to adolescent substance use. Cross-sectional studies associate sleep problems with alcohol use (Pieters et al., 2010). Sleep duration (McKnight-Eily et al., 2011), self-reported sleep problems (Johnson and Breslau, 2001), and insomnia symptoms (Roane and Taylor, 2008) all have been related to concurrent alcohol and cannabis use. Prospective evidence suggests that sleep disturbance precedes substance use. Parent reports of childhood “trouble sleeping” and “overtiredness” predicted boys’ alcohol and cannabis use between ages 12 and 14 (Wong et al., 2004), while adolescent self-endorsement of these behaviors predicted subsequent illicit drug use (Wong et al., 2010). Insomnia in 12 to 19 year-olds was associated with alcohol use one year later (Hasler et al., 2014). In the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, trouble falling asleep and decreased sleep duration were associated with subsequent illicit drug use (Wong et al., 2015). Finally, sleep duration predicted marijuana use two years later (Pasch et al., 2012). This evidence suggests that pediatric sleep is associated with alcohol and cannabis use, but long-term longitudinal studies of adolescent sleep and substance remain rare.

To lend further credence to sleep as a risk factor for adolescent substance use, additional evidence of a temporal relationship between the two is required. In the present project, we hypothesized longitudinal associations between difficulties in early adolescent sleep and substance use among urban, low-income boys. We expected shorter sleep duration and worse sleep quality at age 11 would be associated with earlier and greater alcohol and cannabis use throughout adolescence after accounting for potential third variables. We focused on early adolescent sleep because it captures a key point when puberty-related sleep changes first occur (Kim et al., 2002; Knutson, 2005; Laberge et al., 2001). Additionally, we thought it would be informative to assess sleep before age 14 because initiating substance use by this age increases one’s risk of developing a substance use disorder (DeWit et al., 2000; Hingson et al., 2006). By examining substance use from age 12 through 22, we hope to more precisely describe the relationship between adolescent sleep and subsequent substance use.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Participants

Data utilized came from the Pitt Mother & Child Project, a longitudinal study on vulnerability, resilience, and antisocial behavior in low-socioeconomic status (SES) boys (Shaw et al., 2003, 1999). Unadjusted analyses include 173 and 165 boys for alcohol and cannabis, respectively, drawn from the originally recruited sample of 310 boys and the subset of 186 who completed the sleep assessment (added partway through the age 11 assessment1). Of those 186, some were excluded from the respective analyses for missing data on alcohol (n=13) or cannabis (n=21). Adjusted analyses with all covariates include 145 and 140 boys for alcohol and cannabis, respectively. Other participants were excluded from adjusted analyses for missing data on neighborhood danger (n=1), internalizing/externalizing problem behavior (n=1), and active distraction (n=30). Mann-Whitney U tests show included and excluded participants had similar demographic characteristics at study onset.

2.2 Variables

2.2.1 Sleep Measures

When participants were 11, mothers completed the Child Sleep Questionnaire2 (CSQ), an adaptation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse et al., 1989). Sleep duration was calculated by subtracting night-time wakefulness (time to fall asleep, waking mid-sleep, and waking up early) from estimated time in bed. The scoring system for sleep quality, designed to closely mimic the PSQI, summed 7 variables on a 0–3 scale (continuous variables were recoded as Likert items) with higher numbers indicating worse sleep (Cronbach α=0.63). Variables included sleep duration, sleep latency, mid-sleep disturbance, late-sleep disturbance, maternal impression of sleep quality, day disturbance, and sleep efficiency.

2.2.2 Substance Use

At age 20, participants were interviewed using the Lifetime Drug and Alcohol Use History (Clark et al., 2001; Skinner and Sheu, 1982). Initial and later use of alcohol and cannabis was coded from this interview and again at age 22 to examine use since age 20. Of note, 22 individuals were interviewed only at age 22 due to availability; these participants provided information on their substance use similar to those interviewed at age 20. Variables included age of first use, intoxication, and repeated use, defined as the age when the participant used alcohol ten times or cannabis three times in a year.

2.2.3 Covariates

Minority status (coded dichotomously as White or non-White) was included because of sleep and substance use differences between Whites and Blacks (Chen and Jacobson, 2012; Chen et al., 2015). Family SES at age 11 was measured using the Hollingshead four-factor index score which accounts for parental marital status, education, occupation, and sex (Hollingshead, 1975).

Internalizing and externalizing problems were accounted for given their links to substance use (King et al., 2004; O’Neil et al., 2011). When participants were 11, mothers completed the Child Behavior Checklist, a well-established assessment of child behavior (Achenbach, 1991). The broad-band internalizing (Cronbach α=0.86) and externalizing (Cronbach α=0.92) problem scores were used as covariates.

Neighborhood danger was accounted for because of greater exposure to substances and traumatic events for youth in high-risk neighborhoods (Lowry et al., 1999; Zinzow et al., 2009). At age 11, mothers filled out the Me and My Neighborhood questionnaire which includes 18 Likert-scale items relating to neighborhood danger (e.g., “a friend was stabbed or shot”); higher summed scores indicate increased danger (α=0.88) (PMCP, 2001).

Emotion regulation was accounted for because of its association with substance use (Wills et al., 1995). At age 3.5, child behavior was coded from videotapes of a 3-minute cookie delay-of-gratification task, in which the child has nothing to do while mother fills out a questionnaire and holds onto a clear bag containing a preferred cookie (Marvin, 1977). The number of 10-second intervals spent in active distraction, directly inversely linked to later child problem behavior (Gilliom et al., 2002), was used as a covariate (mean=10.92, SD=5.14).

2.3 Data Analysis

Cox regression was used to model the association between sleep and substance use. The assumption of proportional hazards was tested using Schoenfeld residuals in R 3.2.3. These data do not violate the assumption of proportional hazards.

Hazard models were created using SPSS 23’s “Cox Regression” function with an α=0.05 (Table 1). Individuals were left-censored if they used the substance of interest before age 12 (n=10 for alcohol; n=4 for cannabis). Unadjusted analyses included the sleep variables as continuous variables. Adjusted analyses added all covariates. To facilitate interpretation, the reciprocal sleep duration hazard ratios were recorded.

Table 1.

Age 11 sleep duration and quality as predictors of alcohol and cannabis use in cox regression models

| Predictor

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Duration

|

Sleep Quality

|

|||

| Outcome | HR(95% CI) | p | HR(95% CI) | p |

| Unadjusted Analysis | ||||

| Alcohol | ||||

| First Use | 1.18 (1.04–1.34) | .01 | 1.05 (1.00–1.11) | .08 |

| Intoxication | 1.20 (1.04–1.38) | .01 | 1.06 (1.00–1.12) | .05 |

| Repeated Use | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) | .06 | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | .10 |

| Cannabis | ||||

| First Use | 1.24 (1.06–1.45) | .006 | 1.09 (1.02–1.16) | .007 |

| Intoxication | 1.24 (1.06–1.45) | .008 | 1.09 (1.02–1.15) | .01 |

| Repeated Use | 1.27 (1.08–1.49) | .004 | 1.09 (1.03–1.16) | .005 |

| Adjusted Analysis | ||||

| Alcohol | ||||

| First Use | 1.23 (1.04–1.45) | .01 | 1.09 (1.02–1.18) | .02 |

| Intoxication | 1.27 (1.06–1.52) | .01 | 1.10 (1.02–1.19) | .01 |

| Repeated Use | 1.28 (1.06–1.54) | .01 | 1.12 (1.03–121) | .005 |

| Cannabis | ||||

| First Use | 1.20 (1.01–1.41) | .04 | 1.08 (1.00–1.16) | .29 |

| Intoxication | 1.23 (1.04–1.46) | .02 | 1.10 (1.03–1.19) | .01 |

| Repeated Use | 1.29 (1.08–1.55) | .004 | 1.13 (1.05–1.22) | .001 |

Note. HR = Hazard Ration, CI = Confidence Interval. Adjusted analysis includes the following covariates in the model: race, socioeconomic status, neighborhood danger, externalizing problem behavior, internalizing problem behavior, and active distraction. Sleep duration HRs have been transformed by taking the reciprocal. HRs >1 indicate here that each 1 hour of less sleep duration was associated with x% earlier substance use.

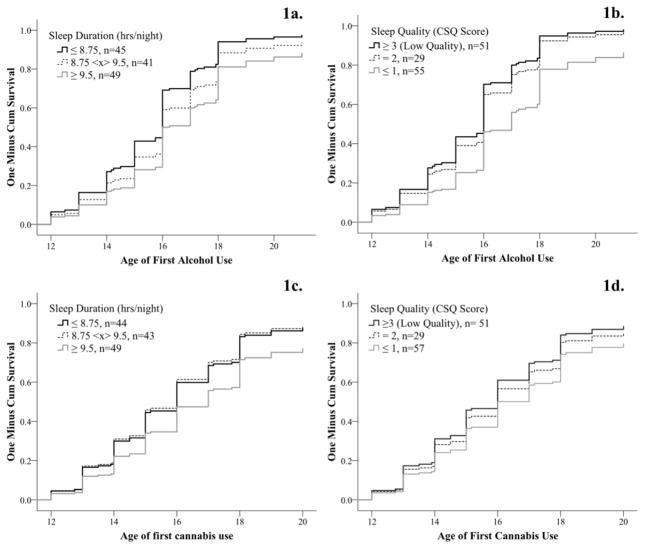

To graphically present results, participants were grouped based on duration (approximate tertiles) and quality (scores of 0–1 in the first group, scores of 2 in the second, and scores of 3+ the third) and one-minus-survival curves for first alcohol and cannabis use were created (Figures 1a–1d).

Figure 1.

For the sake of interpretation, groups were created for both duration and quality and used in regression with all covariates. Earlier alcohol use was noted in groups with lower sleep duration (1a) and worse sleep quality (1b). Likewise, earlier cannabis use was noted in groups with lower sleep duration (1c) and worse sleep quality (1d).

3. RESULTS

For the unadjusted alcohol analyses, less sleep duration was associated with earlier use and intoxication, but not repeated use. Sleep quality was not associated with any outcome. Adjusted analyses showed less sleep duration and lower quality were both associated with earlier alcohol use, intoxication, and repeated use. Greater active distraction was positively associated with earlier alcohol use (HR1.04, p=0.03) and repeated use (HR1.04, p=0.03) in the sleep duration analysis. Covariates were otherwise non-significant.

For the unadjusted cannabis analyses, less sleep duration and lower sleep quality were associated with earlier use, intoxication, and repeated use. Adjusted analyses showed shorter sleep duration was associated with all earlier outcomes. Lower sleep quality was associated with earlier cannabis intoxication and repeated use, but not first use. Higher externalizing problems were associated with earlier cannabis use (HR1.04, p=0.02) and intoxication (HR1.04, p=0.04) in the duration analyses and earlier cannabis use (HR1.04, p=0.046) in the quality analysis. Covariates were otherwise non-significant.

Of note, both quality and duration were non-significant when simultaneously used in regression for all analyses.

Illustrations of group-level hazard analyses (Figure 1a–1d) imply that less sleep duration and worse sleep quality were associated with earlier substance use.

4. DISCUSSION

These results suggest that shorter duration and lower quality of sleep are risk factors for alcohol and cannabis use even when accounting for important covariates. These sleep constructs may pre-dispose adolescents to substance use, a worrying finding considering early substance use is associated with a shortened time to dependence (Clark et al., 1998).

These findings are convergent with prospective studies of sleep’s predictive role in adolescent alcohol and cannabis use (Hasler et al., 2014; Pasch et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2004, 2009, 2015) and a recent CDC report where lower sleep duration was associated with high school students’ risky behavior (Wheaton, 2016). This study is unique in linking two sleep constructs in early adolescence to alcohol and cannabis initiation, intoxication, and repeated use. As there is a dearth of literature linking early adolescent sleep to subsequent substance use, this study provides initial evidence for sleep’s developmental role in substance use.

Sleep disturbance may be an important target of interventions to decrease substance use. For pediatricians, these results warrant the validation of sleep-related screening tools to help identify at-risk adolescents. While effective behavioral treatments for sleep disturbance are available (Mindell and Meltzer, 2008), the area remains under-explored; these results highlight the need to further develop treatment strategies. These results could also suggest policy-level means to decrease substance use, especially as delaying school start times has been shown to improve sleep duration (Owens et al., 2010).

The study includes notable limitations. Importantly, the CSQ’s internal consistency was low, and sleep quality and duration were moderately correlated. Additional research disentangling these constructs – perhaps using actigraphy and sleep diaries – would be informative. Participants resided in Pennsylvania where recreational cannabis use is illegal; thus, these results may not be generalizable to other locations. This sample consisted solely of low-income, urban boys, limiting generalizability to other boys and young women, especially given evidence that sleep does not predict girls’ alcohol and cannabis use (Wong et al., 2009). Although the present study controlled for multiple covariates, additional risk factors to substance use, including parental use, peer use, and access to substances, could not be included. Finally, much of our data is retrospective and subject to memory distortions.

While these results support sleep’s role in adolescent substance use, the extant literature indicates that future work should consider how physical and psychiatric illnesses relate to sleep and substance use. Prior longitudinal data links early childhood sleep problems to adolescent anxiety and depression (Gregory and O’Connor, 2002) and supports bidirectional associations between sleep problems and generalized anxiety disorder and depression in late childhood through adolescence (Shanahan et al., 2014). Less sleep during adolescence is linked to depressive symptoms, alcohol use (Pasch et al., 2010), and comorbid physical conditions (McKnight-Eily et al., 2011). Relatedly, active distraction and externalizing problems were associated with some substance use outcomes in the present study, suggesting future longitudinal studies should consider these variables as potential moderators between sleep and substance use.

In conclusion, these results indicate that sleep is an important risk factor for adolescent substance use. The dramatic normative changes in sleep and emerging substance use during adolescence indicate that this issue deserves strong attention. While more work is needed to understand the role of physical and mental illness, these findings suggest sleep may be a target to decrease substance use throughout adolescence.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Childhood sleep problems may be prospectively linked to adolescent substance use

Less sleep predicted earlier onset of alcohol and cannabis involvement

Worse sleep quality predicted earlier onset of alcohol and cannabis involvement

These associations generally held after accounting for various covariates

Childhood sleep is a promising target for reducing adolescent substance use risk

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This research was funded by several grants through the National Institutes of Health. The National Institutes of Health provided financial support for the project and the preparation of the manuscript but did not have a role in the design of the study, the analysis of the data, the writing of the manuscript, nor the decision to submit the present research.

The authors would like to thank the participants and their parents who participated in this study. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including MH050907 (Shaw), DA026222 (Forbes, Shaw), T32HL082610 (Buysse) and K01DA032557 (Hasler).

Footnotes

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Please see Supplementary Table 1 by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Contributors

The Pitt Mother and Child Project was originally conceived by Daniel Shaw. The present project was designed by Thomas Mike, Erika Forbes, and Brant Hasler. Data analysis was performed by Thomas Mike, Stephanie Sitnick, and Brant Hasler. The manuscript was prepared primarily by Thomas Mike and Brant Hasler with a number of edits from Daniel Shaw, Erika Forbes, and Stephanie Sitnick. All authors were in agreement with the final submitted manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:179–192. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootzin RR, Stevens SJ. Adolescents, substance abuse, and the treatment of insomnia and daytime sleepiness. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:629–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Jenni OG. Regulation of adolescent sleep: implications for behavior. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1021:276–291. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: gender and racial/ethnic differences. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang R, Zee P, Lutsey PL, Javaheri S, Alcantara C, Jackson CL, Williams MA, Redline S. Racial/ethnic differences in sleep disturbances: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Sleep. 2015;38:877–888. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Kirisci L, Tarter RE. Adolescent versus adult onset and the development of substance use disorders in males. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;49:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Pollock NK, Mezzich A, Cornelius J, Martin C. Diachronic substance use assessment and the emergence of substance use disorders. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2001;10:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:745–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS, Beck JE, Schonberg MA, Lukon JL. Anger regulation in disadvantaged preschool boys: strategies, antecedents, and the development of self-control. Dev Psychol. 2002;38:222. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, O’Connor TG. Sleep problems in childhood: a longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:964–971. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler BP, Dahl RE, Holm SM, Jakubcak JL, Ryan ND, Silk JS, Phillips ML, Forbes EE. Weekend-weekday advances in sleep timing are associated with altered reward-related brain function in healthy adolescents. Biol Psychol. 2012a;91:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler BP, Martin CS, Wood DS, Rosario B, Clark DB. A longitudinal study of insomnia and other sleep complaints in adolescents with and without alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:2225–2233. doi: 10.1111/acer.12474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler BP, Smith LJ, Cousins JC, Bootzin RR. Circadian rhythms, sleep, and substance abuse. Sleep Med Rev. 2012b;16:67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatrics Adolesc Med. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index Of Social Status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, Breslau N. Sleep problems and substance use in adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;64:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, Roth T, Schultz L, Breslau N. Epidemiology of DSM-IV insomnia in adolescence: lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and an emergent gender difference. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e247–256. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Use Of Alcohol, Cigarettes, And A Number Of Illicit Drugs Declines Among U.S. Teens. University of Michigan News Service; Ann Arbor, MI: 2014. p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WDS, Balkin TJ, Wesensten NJ. Impaired decision making following 49 h of sleep deprivation. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Dueker GL, Hasher L, Goldstein D. Children’s time of day preference: age, gender and ethnic differences. Pers Individ Diff. 2002;33:1083–1090. [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99:1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL. The association between pubertal status and sleep duration and quality among a nationally representative sample of U. S. Adolescents. Am J Hum Biol. 2005;17:418–424. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge L, Petit D, Simard C, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, Montplaisir J. Development of sleep patterns in early adolescence. J Sleep Res. 2001;10:59–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry R, Cohen LR, Modzeleski W, Kann L, Collins JL, Kolbe LJ. School violence, substance use, and availability of illegal drugs on school property among US high school students. J School Health. 1999;69:347–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1999.tb06427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin RS. Attachment Behavior. Springer; New York: 1977. An Ethological—Cognitive Model for the Attenuation of Mother—Child Attachment Behavior; pp. 25–60. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight-Eily LR, Eaton DK, Lowry R, Croft JB, Presley-Cantrell L, Perry GS. Relationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent students. Prev Med. 2011;53:271–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Meltzer LJ. Behavioural sleep disorders in children and adolescents. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:722–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil KA, Conner BT, Kendall PC. Internalizing disorders and substance use disorders in youth: comorbidity, risk, temporal order, and implications for intervention. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA, Belon K, Moss P. Impact of delaying school start time on adolescent sleep, mood, and behavior. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:608–614. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch KE, Laska MN, Lytle LA, Moe SG. Adolescent sleep, risk behaviors, and depressive symptoms: are they linked? Am J Health Behav. 2010;34:237–248. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.2.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch KE, Latimer LA, Cance JD, Moe SG, Lytle LA. Longitudinal bidirectional relationships between sleep and youth substance use. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41:1184–1196. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9784-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen AK, Räikkönen K, Paavonen EJ, Heinonen K, Komsi N, Lahti J, Kajantie E, Järvenpää AL, Strandberg T. Sleep duration and regularity are associated with behavioral problems in 8-year-old children. Int J Behav Med. 2010;17:298–305. doi: 10.1007/s12529-009-9065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters S, Van Der Vorst H, Burk WJ, Wiers RW, Engels RC. Puberty-dependent sleep regulation and alcohol use in early adolescents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1512–1518. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PMCP. Me and My Neighborhood. University of Pittsburgh; Unpublished results. [Google Scholar]

- Roane BM, Taylor DJ. Adolescent insomnia as a risk factor for early adult depression and substance abuse. Sleep. 2008;31:1351–1356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L, Copeland WE, Angold A, Bondy CL, Costello EJ. Sleep problems predict and are predicted by generalized anxiety/depression and oppositional defiant disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:550–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DS. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Dev Psychol. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Winslow EB, Flanagan C. A prospective study of the effects of marital status and family relations on young children’s adjustment among African American and European American families. Child Dev. 1999;70:742–755. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Sheu WJ. Reliability of alcohol use indices. The Lifetime Drinking History and the MAST. J Stud Alcohol. 1982;43:1157–1170. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence new perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton AG. Sleep Duration and Injury-Related Risk Behaviors Among High School Students—United States, 2007–2013. MMWR. 2016:65. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6513a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, DuHamel K, Vaccaro D. Activity and mood temperament as predictors of adolescent substance use: test of a self-regulation mediational model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;68:901–916. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Sleep problems in early childhood and early onset of alcohol and other drug use in adolescence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:578–587. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000121651.75952.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Nigg JT, Zucker RA. Childhood sleep problems, response inhibition, and alcohol and drug outcomes in adolescence and young adulthood. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1033–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Zucker RA. Childhood sleep problems, early onset of substance use and behavioral problems in adolescence. Sleep Med. 2009;10:787–796. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Robertson GC, Dyson RB. Prospective relationship between poor sleep and substance-related problems in a national sample of adolescents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:355–362. doi: 10.1111/acer.12618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Ruggiero KJ, Hanson RF, Smith DW, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Witnessed community and parental violence in relation to substance use and delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:525–533. doi: 10.1002/jts.20469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.