Abstract

Background

Spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) remains a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality amongst non-anomalous neonates in the United States. SPTB tends to recur at similar gestational ages. Intramuscular 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17OHP-C) reduces the risk of recurrent SPTB. Unfortunately, one-third of high-risk women will have a recurrent SPTB despite 17OHP-C therapy; the reasons for this variability in response are unknown.

Objective

We hypothesized that clinical factors among women treated with 17OHP-C who suffer recurrent SPTB at a similar gestational age differ from women who deliver later, that these associations could be used to generate a clinical scoring system to predict 17OHP-C response.

Study Design

Secondary analysis of a prospective, multi-center, randomized controlled trial enrolling women with ≥1 prior singleton SPTB <37 weeks gestation. Participants received daily omega-3 supplementation or placebo for recurrent PTB prevention; all were provided 17OHP-C. Women were classified as a 17OHP-C responder or non-responder by calculating the difference in delivery gestational age between the 17OHP-C treated pregnancy and her earliest prior SPTB. Responders were women with pregnancy extending ≥3 weeks later compared to the delivery gestational age of their earliest prior PTB; non-responders delivered earlier or within 3 weeks of the gestational age of their earliest prior PTB. A risk score for non-response to 17OHP-C was generated from regression models using clinical predictors, and was validated in an independent population. Data were analyzed with multivariable logistic regression.

Results

754 women met inclusion criteria; 159 (21%) were non-responders. Responders delivered later on average (37.7 +/− 2.5 weeks) than non-responders (31.5 +/− 5.3 weeks), p<0.001. Among responders, 27% had a recurrent SPTB (vs. 100% of non-responders). Demographic characteristics were similar between responders and non-responders. In a multivariable logistic regression model, independent risk factors for non-response to 17OHP-C were each additional week of gestation of the earliest prior PTB (OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.17–1.30, p<0.001), placental abruption or significant vaginal bleeding (OR 5.60, 95% CI 2.46–12.71, p<0.001), gonorrhea and/or chlamydia in the current pregnancy (OR 3.59, 95% CI 1.36–9.48, p=0.010), carriage of a male fetus (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.02–2.24, p=0.040), and a penultimate PTB (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.03–4.25, p=0.041). These clinical factors were used to generate a risk score for non-response to 17OHP-C as follows: Black +1, male fetus +1, penultimate PTB +2, gonorrhea/chlamydia +4, placental abruption +5, earliest prior PTB was 32–36 weeks +5. A total risk score >6 was 78% sensitive and 60% specific for predicting non-response to 17OHP-C (AUC=0.69). This scoring system was validated in an independent population of 287 women; in the validation set, a total risk score >6 performed similarly with a 65% sensitivity, 67% specificity and AUC of 0.66.

Conclusions

Several clinical characteristics define women at risk for recurrent PTB at a similar gestational age despite 17OHP-C therapy, and can be used to generate a clinical risk predictor score. These data should be refined and confirmed in other cohorts, and women at high risk for non-response should be targets for novel therapeutic intervention studies.

Keywords: progesterone supplementation, recurrent preterm birth, spontaneous preterm labor, risk prediction

Introduction

The proportion of babies born preterm in the United States remains unacceptably high at 11.4% (2013).1 The majority of preterm deliveries are spontaneous PTB (SPTB); this encompasses deliveries due to preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), cervical insufficiency, and idiopathic preterm labor.2 A history of a prior SPTB is the biggest risk factor for preterm birth; SPTB recurs in 35–50% of women, and tends to recur at similar gestational ages.3–5 The probability of SPTB also increases with the number of prior SPTB a woman has experienced, with the most recent birth being the most predictive.4,6

In 2003, Meis, et al. published results from a multicenter randomized controlled trial of intramuscular 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC), demonstrating that weekly intramuscular injections beginning at 16–20 weeks gestation reduces the risk of recurrent prematurity by approximately one-third.7 Unfortunately, prophylactic 17OHP-C is not effective for all women, as one-third of high-risk women will have a recurrent PTB despite appropriate prophylaxis with 17OHPC; the reasons for this variable responsiveness are unknown. Limited genetic studies have found associations between genetic variation in the progesterone receptor and nitric oxide genes and clinical response to 17OHP-C.8,9 Other studies have focused on clinical factors in attempts to define the population of women most likely to respond to treatment, finding that those with a family history of PTB and those who experienced bleeding or abruption in the current pregnancy were less likely to respond to 17-OHPC, and those who had a prior spontaneous PTB <34 weeks were more likely to deliver at term with 17-OHPC.10,11

We sought to compare demographic, historical, and antenatal factors between women who delivered at similar gestational age with 17OHP-C for recurrent spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) prevention versus those women who deliver later with 17OHP-C.

Materials and Methods

This is a secondary analysis of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of daily omega-3 supplementation versus placebo for recurrent preterm birth prevention conducted by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network.12 Briefly, women pregnant with a singleton, non-anomalous fetus who had a history of a prior documented singleton SPTB between 20 weeks 0 days gestation and 36 weeks 6 days gestation were recruited between 16 and 22 weeks gestation across thirteen clinical sites between January 2005 and October 2006. All participants received weekly 17OHP-C (beginning at randomization) as a part of the study, and were randomized to receive either a daily supplement of 1,200 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) and 800mg docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3), for a total of 2,000 mg of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (omega-3 group), divided into four capsules, or matching placebo capsules. The 17OHP-C injections were supplied by a company that manages investigational drugs (Eminent Services, Frederick, MD), and were continued until delivery or 36 weeks 6/7 days of gestation, whichever occurred first. Compliance with 17OHP-C injections was calculated as the number received divided by the expected number. Obstetric management was otherwise performed per each woman’s primary obstetric provider. The main study did not find any impact on the rate of PTB prior to 37, 35, or 32 weeks with omega-3 supplementation among women already receiving 17OHP-C.12 Comprehensive obstetric history, longitudinal antenatal data, and detailed delivery information were collected at the time the main study was conducted.

Participants in the original study had the option of providing a maternal peripheral blood DNA sample, for a planned analysis of the relationship between maternal genotype at the –308 position of the TNF-α gene, the –174 position of the IL-6 gene, and the +3954 position of the IL-1β gene and length of gestation and risk of extreme preterm delivery. The procedure for DNA extraction and sample genotyping was performed in accordance with standard methodology.13 The authors found that women homozygous for the minor allele (A) at the –308 position in the promoter region of the TNF-α gene had a significantly shorter length of gestation.13

This secondary analysis used a de-identified data set, and after review by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina, was considered exempt from IRB oversight.

For this analysis, we included all women who had a documented earliest gestational age of prior PTB and with gestational age outcome information available in the current pregnancy. Gestational age was determined by a combination of last menstrual period (if available) and ultrasound.14 We excluded women who received fewer than 50% of expected 17OHP-C injections, regardless of delivery gestational age.

We classified women as a 17OHP-C responder or non-responder by calculating the difference in the gestational age at delivery between the 17OHP-C treated pregnancy and her earliest SPTB, as we have previously described.8,10 To review, the difference between the earliest delivery gestational age and the delivery gestational age with 17OHP-C was calculated, and termed the ‘17OHP-C effect.’ Women with a 17OHP-C effect of ≥3 weeks (i.e., the individual’s pregnancy or pregnancies treated with 17OHP-C delivered at least 3 weeks later compared to the gestational age of the earliest PTB without 17OHP-C treatment) were considered 17OHP-C responders; this designation was made in part by using data originally published by Bloom, et al which showed that 70% of women with recurrent PTB will experience recurrence within 2 weeks of their initial PTB.15 Women with a negative overall 17OHP-C effect and those with an overall 17OHP-C effect of <3 weeks were classified as non-responders. Women with a 17OHP-C effect of <3 weeks but delivering at term (for example, if the earliest prior SPTB was at 35 weeks, and the patient delivered at 37 weeks during the 17OHP-C treated pregnancy) were considered ‘equivocal’ 17OHP-C responders and were excluded from analysis. A separate limited subgroup analysis examining the subset of non-responders who delivered significantly earlier (≤3 weeks earlier) during the 17OHP-C treated pregnancy was also performed (‘possible harm’) group.

Bivariate analyses were conducted to compare 17OHP-C responders to non-responders using t-test, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Genotype data were assessed using the additive model of inheritance (each copy of the minor allele was hypothesized to confer additional risk), and in the bivariate analysis, were analyzed separately by self- reported race/ethnicity group to reduce the chance of analytic error due to population stratification. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with non-response to 17OHP-C, using backwards variable selection, retaining all factors with p<0.20 in the final model.

Finally, a clinical prognostic score was developed. We used the final multivariable model as described in the methods above, and then retained only factors readily available during the antenatal period (e.g., we excluded genotype information and any data only available postnatally). A score was then derived for each prognostic variable using odds ratio estimates; each odds ratio coefficient was divided by the smallest odds ratio coefficient and rounded up to the nearest 0.5 to produce a weighted score. Each woman was then assigned a risk score using this calculation, and the value of this score in predicting non-response to 17P was then assessed. A statistical ‘cut-point’ was determined based on the risk score where the sensitivity and specificity were maximized, using the Liu method.16 The model was then validated using de-identified data from the randomized trial of 17OHP-C vs. placebo conducted by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network.7

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13.1 (College Station, TX). For modeling, fewer than 5% of data were missing, so missing data were imputed by replacing missing values with the median for continuous variables and with the most frequent category for categorical variables, which works as well as multiple imputation with this small proportion of missing data.17 A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

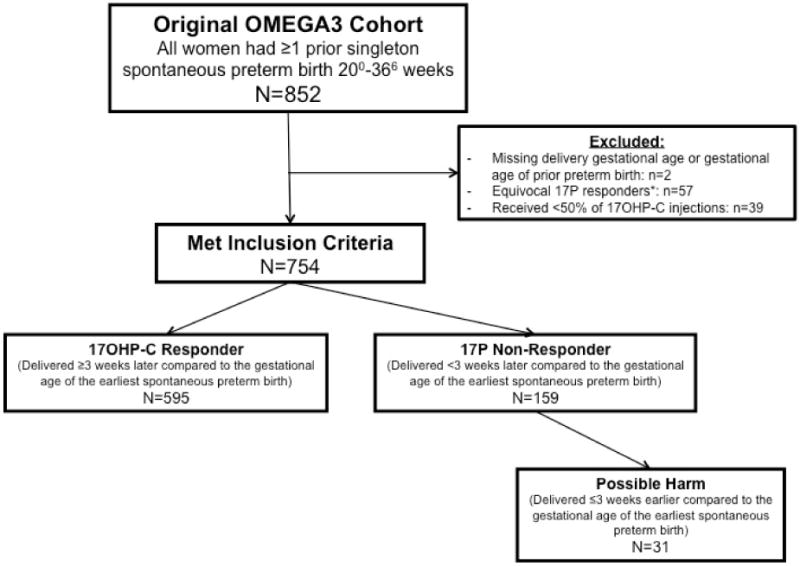

From the original cohort of 852 women enrolled in the omega-3 RCT, 754 met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of note, 57/852 (6.7%) women from the original cohort had a 17OHP-C effect <3 weeks yet delivered at term because their earliest prior PTB was more than 34 weeks gestation; these women were considered ‘equivocal’ responders and were excluded (Figure 1). Of the remaining women, 595/754 (78.9%) delivered at least 3 weeks later compared to the delivery gestational age of their previous earliest PTB and were considered 17OHP-C responders, and 159 (21.1%) had a 17OHP-C effect <3 and were considered non-responders. Of the 159 non-responders, 31 (19.4%) delivered ≥3 weeks earlier with 17OHP-C. On average, responders delivered later (37.7 +/− 2.5 weeks) than non-responders (31.5 +/− 5.3 weeks), p<0.001. Overall, 160/595 responders (26.9%) had a recurrent SPTB, but they were considered responders because they delivered ≥3 weeks later compared to their earliest SPTB.

Figure 1. Study enrollment.

*Equivocal 17P responders: Earliest prior preterm birth was 35–36 weeks, delivered during early term period (37–38 weeks), see text for details

Many demographic characteristics were similar between responders and non-responders, although non-responders were more likely to be White, and less likely to be of Hispanic ethnicity (Table 1). The gestational age of the earliest prior SPTB was later among non-responders (32.3 ± 4.1 vs. 29.1 ± 4,5, p<0.001), but both groups had a similar number of prior SPTB (1.4 ± 0.6 vs. 1.4 ± 0.7, p=0.597), similar chance of having had multiple SPTB (34.6% vs. 28.4%, p=0.129), and similar proportion had one or more previous term deliveries (28.9% vs. 35.3%, p=0.132). The majority of women had a penultimate pregnancy delivering preterm; this did not vary by responder status (92.3% vs. 87.8%, p=0.121, Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic factors and prior pregnancy history by 17OHP-C responder status.

| 17OHP - C non-responder (n=159) |

17OHP - C responder (n=595) |

P - value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Maternal age (mean, ± SD) | 27.1 ± 5.8 | 27.9 ± 5.5 | 0.121 |

|

| |||

| Maternal race, n (%) | 0.001 | ||

| Black | 53 (33.3) | 199 (33.5) | |

| White | 93 (58.5) | 278 (46.7) | |

| Other | 13 (8.2) | 118 (19.8) | |

|

| |||

| Maternal Hispanic ethnicity, n (%) | 11 (6.9) | 100 (16.8) | 0.002 |

|

| |||

| Gestational age of earliest prior spontaneous preterm birth (mean, ± SD) | 32.3 ± 4.1 | 29.1 ± 4.5 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Penultimate pregnancy delivered preterm, n(%) | 147 (92.5) | 525 (88.2) | 0.121 |

|

| |||

| Number of prior spontaneous preterm births (mean, ± SD) | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.597 |

|

| |||

| More than one prior spontaneous preterm birth, n (%) | 55 (34.6) | 169 (28.4) | 0.129 |

|

| |||

| One or more previous term birth(s), n(%) | 46 (28.9) | 210 (35.3) | 0.132 |

|

| |||

| Gestational age at randomization and initiation of 17OHP-C, weeks (mean, ± SD) | 19.5 ± 1.7 | 19.3 ± 1.7 | 0.198 |

|

| |||

| 17OHP-C injection compliance, median % (IQR) | 100 (92, 100) | 100 (93, 100) | 0.022 |

Abbreviations = 17OHP-C: 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate; IQR: interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles)

Several current pregnancy factors were also similar between 17OHP-C responders and non-responders. However, non-responders were more likely to experience clinically significant vaginal bleeding or be diagnosed with a placental abruption in the current gestation (11.3% vs. 3.2%, p<0.001), and were also more likely to be diagnosed with gonorrhea and/or chlamydia during pregnancy (6.9% vs. 2.2%, p=0.003, Table 2). As expected, due to the higher rate of PTB among non-responders, this group was also more likely to receive antenatal corticosteroids (27.0% vs. 28.5%, p=0.017), tocolysis (32.7% vs. 18.0%, p<0.001), and be admitted to the hospital for tocolysis or preterm labor symptoms (Table 2). Non-responders were also more likely to carry a male fetus (57.9% vs. 47.9%, p=0.026, Table 2).

Table 2.

Current pregnancy factors by 17OHP-C responder status.

| 17OHP - C non-responder (n=159) |

17OHP - C responder (n=595) |

P - value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index (kg/m2), mean +/− SD | 26.0 +/− 6.6 | 26.7 +/− 6.7 | 0.284 |

| Smoked during pregnancy, n (%) | 26 (16.4) | 94 (15.8) | 0.865 |

| One or more episode(s) of vaginal bleeding or diagnosis of clinical abruption, n (%) | 18 (11.3) | 19 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| Bacterial vaginosis, n(%) | 11 (23.4) | 43 (33.1) | 0.217 |

| Trichomonas during pregnancy, n(%) | 2 (4.3) | 14 (10.8) | 0.182 |

| Gonorrhea and/or chlamydia infection during pregnancy, n(%) | 11 (6.9) | 13 (2.2) | 0.003 |

| Short cervix <2.50cm*, n (%) | 4 (6.8) | 9 (3.0) | 0.243 |

| Cervical cerclage, n(%) | 4 (2.5) | 12 (2.0) | 0.698 |

| Randomized to receive omega3 capsules, n(%) | 81 (50.9) | 301 (50.6) | 0.937 |

| Received antenatal corticosteroids, n(%) | 43 (27.0) | 110 (18.5) | 0.017 |

| Received tocolysis, n(%) | 52 (32.7) | 107 (18.0) | <0.001 |

| Median number of hospital admissions for tocolysis (IQR) | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 0) | <0.001 |

| Male fetus | 92 (57.9) | 285 (47.9) | 0.026 |

among 355 women with at least one transvaginal cervical length assessment

Abbreviations = 17OHP-C: 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate; IQR: interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles)

Next, we evaluated the relationship between the three maternal genotypes and 17OHP-C response (Tables 3 and 4). For both Black women and White/Hispanic women, there was a trend towards a relationship between maternal IL-1β+3954 genotype and 17OHP-C response, but this did not reach statistical significance (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Genotype results for Black women, by 17OHP-C responders status.

| 17OHP-C Non-responders n=50 |

17OHP-C Responders n=198 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| IL-6-174*, n (%) | 0.115 | ||

| CC* | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| GC | 9 (18.0) | 44 (22.2) | |

| GG | 40 (80.0) | 154 (77.8) | |

|

| |||

| TNFα-308*, n (%) | 0.361 | ||

| AA* | 1 (2.0) | 4 (2.0) | |

| AG | 7 (14.0) | 46 (23.2) | |

| GG | 42 (84.0) | 148 (74.8) | |

|

| |||

| IL-1β+3954*, n (%) | 0.062 | ||

| TT* | 3 (6.0) | 3 (1.5) | |

| CT | 7 (14.0) | 49 (24.8) | |

| CC | 40 (80.0) | 146 (73.7) | |

homozygous minor allele

Genotype data available for 248/252 (98%) of Black women.

Abbreviations = 17OHP-C: 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate

Table 4.

Genotype results for White and Hispanic/non-Black women, by 17OHP-C responders status.

| 17OHP-C Non-responders n=103 |

17OHP-C Responders n=363 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| IL-6-174*, n (%) | 0.990 | ||

| CC* | 14 (13.6) | 48 (13.1) | |

| GC | 47 (46.6) | 169 (46.2) | |

| GG | 42 (40.8) | 149 (40.7) | |

|

| |||

| TNFα-308*, n (%) | 0.157 | ||

| AA* | 4 (3.9) | 4 (1.1) | |

| AG | 27 (26.2) | 95 (26.2) | |

| GG | 72 (69.9) | 264 (72.7) | |

|

| |||

| IL-1β+3954*, n (%) | 0.051 | ||

| TT* | 8 (7.8) | 16 (4.4) | |

| CT | 41 (39.8) | 112 (30.6) | |

| CC | 54 (52.4) | 238 (65.0) | |

homozygous minor allele

Genotype data available for 466/482 (97%) of White and Hispanic/non-Black women

Abbreviations = 17OHP-C: 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate

In regression models, each additional week of gestation of the earliest prior SPTB (OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.17–1.30, p<0.001), placental abruption or significant vaginal bleeding in the current pregnancy (OR 5.60, 95% CI 2.46–12.71, p<0.001), diagnosis with gonorrhea and/or chlamydia in the current pregnancy (OR 3.59, 95% CI 1.36–9.48, p=0.010), carriage of a male fetus (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.02–2.24, p=0.040), and a penultimate pregnancy delivering preterm (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.03–4.25, p=0.041) were associated with an increased likelihood of non-response to 17OHP-C (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression model. Shown are factors associated with non-response to 17OHP-C.

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age of earliest prior preterm birth (each additional week) | 1.23 | 1.17–1.30 | <0.001 |

| Placental abruption or significant vaginal bleeding in the current pregnancy | 5.60 | 2.46–12.71 | <0.001 |

| Gonorrhea and/or chlamydia in the current pregnancy | 3.59 | 1.36–9.48 | 0.010 |

| Male fetus | 1.51 | 1.02–2.24 | 0.040 |

| Penultimate pregnancy delivered preterm | 2.10 | 1.03–4.25 | 0.041 |

| Maternal Interleukin-1 beta genotype (per each copy of the minor allele) | 1.31 | 0.94–1.82 | 0.114 |

| Black race | 1.37 | 0.88–2.15 | 0.165 |

Additional factors considered in model included: randomization group, maternal tumor necrosis factor alpha genotype, maternal interleukin 6 genotype; these were removed from the final model due to p>0.20.

Abbreviations = 17OHP-C: 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate

Next, we developed a prognostic scoring system for non-response to 17-OHPC using the results from the logistic regression model (Table 5). To create the risk scoring model, the IL-1β genotype factor variable was removed from the model in Table 5 as this is infrequently available clinically. Furthermore, the gestational age at the earliest prior PTB was converted to a dichotomous variable using cut-point calculations; it was determined that risk was highest at or beyond 32 weeks gestation. The scoring system model performed moderately well overall with an AUC of 0.73 +/− 0.02. The final risk prediction model is shown in Table 6. Each individual was then assigned a risk score based on this scoring system. For example, a Black woman (+1) carrying a female fetus (+0), with no gonorrhea or chlamydia (+0), a current diagnosis of abruption (+5), whose last and only other baby was delivered preterm (+2) at 29 weeks (+0) would have a total risk score of 8. Scores ranged from 0 to 18 in this cohort, with a median score of 6 (IQR 3, 8). Each additional point was found to increase the odds of non-response to 17OHP-C by 37% (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.28–1.48, p<0.001). When a cut-off of >6 was used to classify women at high risk for non-response to 17OHP-C, the sensitivity of the risk score was 0.78 (95% CI 0.71–0.84) and the specificity 0.60 (95% CI 0.56–0.64), with an AUC of 0.69 (95% CI 0.65–0.73). The positive predictive value was 0.34 (95% CI 0.30–0.40), and the negative predictive value was 0.91 (95% CI 0.88–0.94). Results were similar if only women with a penultimate PTB were considered (results not shown).

Table 6.

Risk scoring system to assess likelihood of non-response to 17OHP-C.

| Base Score | 0 |

| Male fetus | +1 |

| Black race | +1 |

| Last pregnancy delivered preterm | +2 |

| Gonorrhea and/or chlamydia in the current pregnancy | +4 |

| Placental abruption or significant vaginal bleeding in the current pregnancy | +5 |

| Earliest prior preterm birth was 32 – 36 weeks gestation | +5 |

| SUM to get score | Possible range = 0 to 18 |

The scoring system was then validated using de-identified data from the Meis RCT of 17OHP-C vs. placebo. The Meis study enrolled 463 women; two-thirds (310) were randomized to receive 17OHP-C, of these, 4 were excluded due to a missing 17OHP-C effect, and 19 were excluded because they were classified as equivocal 17OHP-C responders. Among the remaining 287 women in the validation set, 63 (22.0%) were non-responders. In the validation set, scores ranged from 0 to 14, with a median score of 4 (IQR 3, 8). Each additional point was found to increase the odds of non-response to 17OHP-C by 32% (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.19–1.47, p<0.001). When a cut-off of >6 was used to classify women at high risk for non-response to 17OHP-C, the sensitivity of the risk score was 0.65 (95% CI 0.52–0.77) and the specificity 0.66 (95% CI 0.60–0.73), with an AUC of 0.66 (95% CI 0.59–0.72). The positive predictive value was 0.35 (95% CI 0.27–0.45), and the negative predictive value was 0.87 (95% CI 0.81–0.92).

Finally, we performed a limited subgroup analysis examining the 31 women in the main cohort who delivered significantly earlier (≥3 weeks) with 17OHP-C compared to the gestational age of their earliest prior PTB, a potential ‘harm’ group (Figure 1). These 31 women delivered at a mean 26.3 +/− 4.0 weeks gestation during the 17OHP-C treated pregnancy, compared to their previously earliest PTB, which occurred at a mean 32.4 +/− 3.7 weeks gestation. A significantly higher proportion of women in the potential harm group, 20/31 (64.5%) were Black, compared to 33/128 (25.8%) of other non-responders and 199/595 (33.5%) of responders, p<0.001. Compared to the other non-responders, women delivering significantly earlier were also more likely to be diagnosed with a short cervical length <2.50cm during pregnancy (3/14, 21.4% vs. 1/45, 2.2%, p=0.038), and had a trend towards even higher rates of placental abruption (19.4% vs. 9.4%, p=0.116). However, other characteristics were similar between women in the potential harm group compared to the other non-responders. Unfortunately, the small number of women in this subgroup precluded additional regression analyses.

Comment

We have identified several risk factors for non-response to 17OHP-C, including the gestational age of the previous earliest PTB, placental abruption in the current pregnancy, gonorrhea or chlamydia infection, and male fetus. Furthermore, Black race and maternal IL-1β+3954 genotype may also influence the likelihood of response to 17OHP-C. We have generated a preliminary risk scoring system for non-response to 17OHP-C using these findings. Unfortunately, response to 17OHP-C remains imperfect and further refinement is necessary before clinical application. These data add to a growing body of literature suggesting that women who experience a recurrent PTB or recurrent PTB at a similar gestational age while receiving 17OHP-C have distinctly different clinical and biologic characteristics than those who receive 17OHP-C and deliver at term.8,10,11,18

These results are consistent with and confirm our previous results from a separate cohort of women at high risk for recurrent SPTB.10 Our prior study included 155 women; 37 (24%) were classified as non-responders, which is similar to the 21% non-responder rate in the current study. In that study, we also identified the gestational age of the earliest previous spontaneous PTB, significant vaginal bleeding or abruption, first-degree family history of SPTB, and preterm birth of the penultimate pregnancy as risk factors for reduced response to 17OHP-C.10 We have confirmed these results in the current study. We were unable to evaluate family history in the current report, as this information was not collected as part of the original RCT. The current study includes a substantially larger number of subjects than our previous report and therefore allows for additional power to detect other risk factors associated with 17OHP-C response, including fetal sex, Black race, and maternal genital tract infection with gonorrhea or chlamydia. The risk scoring system presents a simplified summary of results of the logistic regression, in a manner that is easy to clinically interpret.

We found that women carrying male fetuses had an increased likelihood of non-response to 17OHP-C. This extends previous observations that male sex increases the risk of preterm birth and is associated with worse neonatal outcomes.19,20 Black race is an established risk factor for SPTB, and multiple studies have demonstrated that Black women have earlier PTB and are more likely to have recurrent PTB.21 Although a similar proportion of Black women were responders and non-responders in bivariate analysis, Black race remained in final regression models predicting non-response, and confers one point in the risk score. Furthermore, a large proportion of women (20/31, or 64.5%) in the potential harm group were of Black race. Although Black women are known to be at higher risk for recurrent PTB compared to white women, the finding of earlier PTB with 17OHP-C is novel. Caution should be advised when drawing conclusions based on these data, however, given the small number of women in this subgroup.

This study is not without limitations. As with any secondary analysis, we were limited by the data collected during the original study. Unfortunately, we do not have information regarding family history of PTB, nor do we have detailed information regarding prior pregnancy phenotype (e.g., history of preterm premature rupture of membranes, or history of cervical insufficiency). Due to small numbers and population stratification issues, we were unable to examine the relationship between genotype and response. We do not have information regarding 17P exposure in previous pregnancies, though this is likely negligible as 70% of this population had only one previous PTB and the current gestation was their first 17P eligible pregnancy, and many others included here would have had pregnancies prior to the publication of the Meis trial in June 2003. Likewise, the small numbers of potential harm subjects also prevented us from performing a regression analysis in this subset of women. Additionally, the risk factors identified in the logistic regression model are all known risk factors for SPTB; given the design of the parent study, we are unable to conclude causality between 17OHP-C treatment and outcome.

This study also has several strengths. This is a very high-risk cohort; all subjects had at least one prior documented SPTB and 90% had a penultimate PTB. In contrast to the majority of studies of 17OHP-C, the injections in both the main analysis and validation set were a proscribed part of the study protocol and compliance carefully documented. All data were prospectively collected and the study was conducted across the United States at tertiary care centers representative of maternal-fetal medicine and obstetric care received by women at high risk for PTB. Further, we were able to consider limited genetic data with clinical factors to determine likelihood of response to 17OHP-C. Our definition of 17OHP-C response is clinically relevant, because at periviable gestational ages, pregnancy prolongation of even 3 weeks increases the probability of neonatal survival from 7 to 77%.22,23

Although promising, additional refinement and further external validation is needed prior to clinical implementation of the risk-scoring model. With the addition of more patients and high-quality data, future studies should work to improve the AUC to better discriminate responders and non-responders. Although there are currently no alternate therapies to 17OHP-C (in the setting of a high or positive risk score for non-response), the negative predictive value was high for both the test and validation cohorts, and may provide reassurance to some women. This is an example of an easy to understand, simple clinical application of these data to real world patient care settings.

It should be emphasized that while these data are consistent with our previous findings10 and provide additional information and insight regarding the likelihood of response to 17OHP-C, they are insufficient to recommend changes in clinical practice. As described above, although the risk-scoring model may identify women at highest risk for non-response to 17OHP-C, there are currently no acceptable alternative or adjunct therapies. At this time, we continue to recommend, in accordance with current SMFM and ACOG guidelines, that all women with a history of a prior singleton SPTB prior to 37 weeks gestation are offered weekly 17OHP-C beginning at 16–20 weeks.24,25 Future studies should incorporate clinical and genetic factors such as those reported here to identify individuals who may be the best candidates for alternative or additional therapies for SPTB prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and George Washington University Biostatistical Coordinating Center staff for making this dataset available for analysis. The comments of this report represent the views of the authors and do not represent the views of the NICHD, the NICHD Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network, or the National Institutes of Health.

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study.

Funding: This study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development 5K23HD067224 (Dr. Manuck).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement: Dr. Sean Esplin serves on the scientific advisory board and holds stock in Sera Prognostics, a private company that was established to create a commercial test to predict preterm birth and other obstetric complications. Dr. Tracy Manuck is also on the scientific advisory board for Sera Prognostics. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Presentation: None.

Reprints will not be available.

References

- 1.Schoen CN, Tabbah S, Iams JD, Caughey AB, Berghella V. Why the United States preterm birth rate is declining. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson JJ, McWilliam OA, Newnham JP, Pennell CE. Preterm birth aetiology 2004–2008. Maternal factors associated with three phenotypes: spontaneous preterm labour, preterm pre-labour rupture of membranes and medically indicated preterm birth. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. 2012;25:642–7. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.597899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams MM, Elam-Evans LD, Wilson HG, Gilbertz DA. Rates of and factors associated with recurrence of preterm delivery. Jama. 2000;283:1591–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esplin MS, O’Brien E, Fraser A, et al. Estimating recurrence of spontaneous preterm delivery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;112:516–23. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318184181a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonsen SE, Lyon JL, Stanford JB, Porucznik CA, Esplin MS, Varner MW. Risk factors for recurrent preterm birth in multiparous Utah women: a historical cohort study. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2013;120:863–72. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManemy J, Cooke E, Amon E, Leet T. Recurrence risk for preterm delivery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;196:576 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.039. discussion e6–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manuck TA, Watkins WS, Moore B, et al. Pharmacogenomics of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for recurrent preterm birth prevention. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;210:321 e1–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manuck TA, Lai Y, Meis PJ, et al. Progesterone receptor polymorphisms and clinical response to 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;205:135 e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manuck TA, Esplin MS, Biggio J, et al. Predictors of response to 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:376 e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spong CY, Meis PJ, Thom EA, et al. Progesterone for prevention of recurrent preterm birth: impact of gestational age at previous delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1127–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harper M, Thom E, Klebanoff MA, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation to prevent recurrent preterm birth: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:234–42. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd60e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper M, Zheng SL, Thom E, et al. Cytokine gene polymorphisms and length of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:125–30. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318202b2ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dombrowski MP, Schatz M, Wise R, et al. Asthma during pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2004;103:5–12. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000103994.75162.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloom SL, Yost NP, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Recurrence of preterm birth in singleton and twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:379–85. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X. Classification accuracy and cut point selection. Stat Med. 2012;31:2676–86. doi: 10.1002/sim.4509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York: Spriinger-Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manuck TA, Major HD, Varner MW, Chettier R, Nelson L, Esplin MS. Progesterone receptor genotype, family history, and spontaneous preterm birth. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2010;115:765–70. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d53b83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glass HC, Costarino AT, Stayer SA, Brett CM, Cladis F, Davis PJ. Outcomes for extremely premature infants. Anesth Analg. 2015;120:1337–51. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manuck TA, Sheng X, Yoder BA, Varner MW. Correlation between initial neonatal and early childhood outcomes following preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:426 e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeFranco EA, Hall ES, Muglia LJ. Racial disparity in previable birth. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;214:394 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Trends in Care Practices, Morbidity, and Mortality of Extremely Preterm Neonates, 1993–2012. Jama. 2015;314:1039–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klebanoff MA. 17 Alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm prevention: issues in subgroup analysis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;214:306–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee waoVB. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:376–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics TACoO, Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no 130: prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:964–73. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]