Abstract

Background

Objectives were to: (1) quantify practitioner variation in likelihood to recommend a crown; and (2) test whether certain dentist, practice, and clinical factors are significantly associated with this likelihood.

Methods

Dentists in the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network completed a questionnaire about indications for single-unit crowns. In four clinical scenarios, practitioners ranked their likelihood of recommending a single-unit crown. These responses were used to calculate a dentist-specific “Crown Factor” (CF; range 0–12). A higher score implies a higher likelihood to recommend a crown. Certain characteristics were tested for statistically significant associations with the CF.

Results

1,777 of 2,132 eligible dentists responded (83%). Practitioners were most likely to recommend crowns for teeth that were fractured, cracked, endodontically-treated, or had a broken restoration. Practitioners overwhelmingly recommended crowns for posterior teeth treated endodontically (94%). Practice owners, Southwest practitioners, and practitioners with a balanced work load were more likely to recommend crowns, as were practitioners who use optical scanners for digital impressions.

Conclusions

There is substantial variation in the likelihood of recommending a crown. While consensus exists in some areas (posterior endodontic treatment), variation dominates in others (size of an existing restoration). Recommendations varied by type of practice, network region, practice busyness, patient insurance status, and use of optical scanners.

Practical Implications

Recommendations for crowns may be influenced by factors unrelated to tooth and patient variables. A concern for tooth fracture -- whether from endodontic treatment, fractured teeth, or large restorations -- prompted many clinicians to recommend crowns.

Keywords: Dentistry, Prosthodontics, Crowns

INTRODUCTION

Dentists recommend single-unit crowns for many reasons. A tooth might have a large carious lesion, a fracture, or a large filling, putting the tooth at risk for further breakdown. A tooth might be a source of pain, suggesting a crack, or a tooth might have had endodontic treatment. These situations may prompt a dentist to recommend a crown in order to increase the tooth’s longevity and optimize the patient’s oral health.1

However, little scientific evidence exists to guide dentists when making certain treatment recommendations.2, 3 Most dentists would agree, for example, that a large restoration might be a reason to recommend a crown for a particular tooth. The question then becomes, “Exactly how ‘large’ does a restoration have to be in order to justify recommending a crown for the tooth?” Some dentists might repair a particular restoration, others may replace it, and still others may recommend placing an inlay or a single-unit crown. 4–6

When making treatment recommendations, practitioners must manage a complex mix of clinical, social, and diagnostic factors.7, 8 They base their recommendations on patient assessment, perceived risks and benefits, personal preference, treatment cost, and clinical experience.9 These complexities lead to variation in treatment recommendations between practitioners.10–13 Some treatment recommendations are not directly related to the clinical circumstance of the tooth. 14 For example, patients with a college education may be less likely to receive a recommendation for a crown.15, 16

In circumstances for which clinical scientific evidence is absent, clinicians may gain valuable insight by observing colleagues and knowing what techniques are reported by other dentists as effective. The results presented in this study detail clinicians’ treatment decisions for single-unit crowns and what factors lead to these recommendations. Additionally, we identify non-patient factors that may influence the decision to recommend a crown. The objectives for this study were to: (1) describe and quantify practitioner variation in likelihood to recommend a single-unit crown; and (2) test whether certain dentist, practice, and clinical factors are significantly associated with this likelihood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is based on a questionnaire completed by dentists in the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN; “network”). The network is a consortium of dental practices and dental organizations focused on improving the scientific basis for clinical decision-making.17 Detailed information about the network is available at its web site.18 The network’s applicable Institutional Review Boards approved the study; all participants provided informed consent after receiving a full explanation of the procedures.

Enrollment Questionnaire

As part of the enrollment process, practitioners completed an Enrollment Questionnaire that describes themselves, their practice(s), and their patient population. This questionnaire is publicly available at “http://www.nationaldentalpbrn.org/study-results.php” under the heading “Factors for Successful Crowns” and collects information about practitioner, practice and patient characteristics. Questionnaire items, which had documented test/re-test reliability, were taken from our previous work in a practice-based study of dental care.19, 20 The typical enrollee completes the questionnaire online, although a paper option is available.

Study Questionnaire Development

The questionnaire for this study was developed by a study group of the authors, dentists with clinical expertise, statisticians, and laboratory technicians. Its purpose was to measure current practices in fabricating crowns, and treatment recommendations for single-unit crowns. The survey was reviewed by IDEA Services (Instrument Design, Evaluation, and Analysis Services, Westat, Rockville, MD), a group with expertise in questionnaire development and implementation, as well as National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) program officers and practitioners with prosthodontic content expertise. After extensive internal review, IDEA Services pre-tested the questionnaire via cognitive interviewing by telephone with a regionally diverse group of eight practicing dentists. Cognitive interviewers probed the dentist’s comprehension of each question. The interviewers also asked practitioners to identify items of clinical interest that were not addressed in the survey. Results from the pretest prompted further modification of the questionnaire.

Dentists enrolled in the network were eligible for the study if they met all of these criteria: (1) completed an Enrollment Questionnaire; (2) were currently practicing and treating patients in the United States; (3) were in the network’s “limited” or “full” network participation category; and (4) reported on the Enrollment Questionnaire that they currently do at least some restorative dentistry in their practices. A total of 2,299 network clinicians met these criteria.

Pre-printed invitation letters were mailed (postal) to eligible practitioners, informing them that they would receive an email with a link to the electronic version of the questionnaire. At the time of the email, practitioners were given the option to request a paper version of the survey, as this has been shown to improve response rates.21 Practitioners were asked to complete the questionnaire within two weeks. A reminder letter was sent after the second and fourth weeks to those who had not completed the questionnaire. After six weeks, email and postal reminders were sent with a printed version of the questionnaire and practitioners were offered the option of completing the online or paper versions. After eight weeks, a final postal questionnaire attempt was made with a letter that also encouraged the dentist to complete the questionnaire online. Data collection was closed after 12 weeks from the original email invitation. Practitioners or their business entities were remunerated $75 for completing the questionnaire if desired. Data were collected from February 2015 to August 2015.

Questionnaire Content

The first question of the survey confirmed that the invited clinician did at least one crown in a typical month. The Questionnaire is publicly available (http://www.nationaldentalpbrn.org/study-results.php) under the heading “Factors for Successful Crowns”. Among other questions, practitioners were asked why they recommended crowns for patients. Dentists were asked, “Rank the top three MOST COMMON reasons you recommend a crown in your practice, with 1 being the most common and 3 being the least common,” and were given the following list: Active caries, Endodontic Therapy, Large Restoration, Broken Restoration, Esthetics, Change Vertical Dimension, RPD Abutment, and Other. The Other category received a large number of responses related to fractured teeth or cracked teeth; these were categorized subsequently during data analysis into an additional group labeled Fractured or Cracked Tooth.

Crown Factor

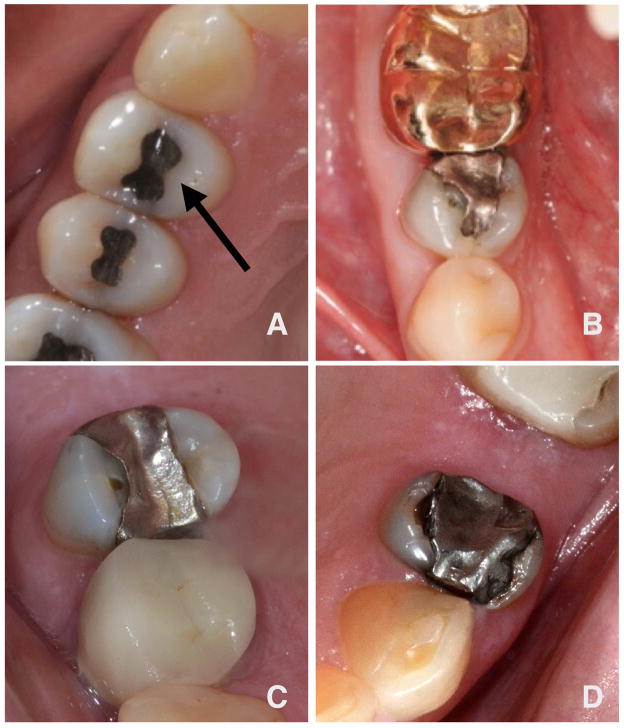

We had a particular interest in learning which restorations would indicate the need for a crown based primarily on the size and condition of the restoration and tooth. A series of four questions showed photographs of teeth with various restorations. Practitioners were asked if they would recommend a crown for each of the four teeth represented (shown in Fig. 1 from smallest to largest; in the questionnaire these were in a mixed order). Practitioners were given this clinical scenario to accompany the four figures: “Assume each patient is a 40 year-old female patient of yours who attends her annual recall visits on a dependable basis, has no relevant medical history, is at low risk for dental decay, has satisfactory occlusion with minimal wear, and is financially able to pay for a crown out-of-pocket.”

Fig. 1.

The four response options were “very likely to recommend a crown,” “likely to recommend a crown,” “not likely to recommend a crown,” and “definitely not recommend a crown.” These were assigned a value of 3, 2, 1 and 0, respectively. The answers to the four questions for each clinician were summed to create a “Crown Factor” (CF; range 0–12) for each dentist. Practitioners who did not answer any of the four questions were excluded from this part of the study.

Other responses on this questionnaire and from the network’s Enrollment Questionnaire were tested to determine whether they were significantly (p<0.05) associated with the Crown Factor. These were questions relating to practice type, years in practice, perceived practice busyness, and insurance coverage of patients.

Statistical Analyses

Power analysis was conducted based on an anticipated sample size of 1,500 completed questionnaires. This sample size would yield sufficient precision to estimate response percentages within ±2.53%, at the 95% confidence level. To document test/re-test reliability of the questionnaire items, 47 respondents completed the questionnaire twice online. For categorical responses, kappa and weighted kappa were used; for numeric items, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to determine test-retest reliability. Descriptive statistics are presented as counts and percentages for categorical variables, and as means and standard deviations for continuous measures. Potential predictors of crown factor were evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multiple regression analysis.

RESULTS

For this study, 2,299 dentists were selected to participate. Of these dentists, 101 were deemed ineligible before beginning the questionnaire (no longer in active practice; deceased; specialists who do not do single-unit permanent crowns). An additional 66 were deemed ineligible once completing at least part of the questionnaire (do not do at least one crown each month). This left a total of 2,132 eligible persons, of whom 1,777 responded, for a response rate of 83%. Among the 47 test/re-test participants, the mean (SD) time between test and re-test was 15.5 (3.0) days. For categorical variables, agreement between time 1 and time 2 showed a mean weighted kappa of 0.62 (IQR: 0.46, 0.79). Mean test-retest reliability for numeric variables was 0.75.

Dentist and practice characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority of respondents were male, and many had been in practice for over 20 years. Most of the respondents, 73%, were practice owners. Respondents were split fairly evenly across regions, and the majority work full time (86%). Only 3% of respondents were specialists, including 32 prosthodontists.

Table 1.

Characteristics of dentists participating in survey

| Characteristics | Number1 (n=1,777) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Dentist Characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1282 | 73 |

| Female | 483 | 27 |

|

| ||

| Years Since Dental School Graduation | ||

| <10 | 292 | 16 |

| 10–19 | 367 | 21 |

| 20–29 | 382 | 22 |

| 30+ | 733 | 41 |

|

| ||

| Type of Practice | ||

| Owner of Private Practice | 1295 | 73 |

| Associate in Private Practice | 207 | 12 |

| Health Partners2 | 44 | 3 |

| Permanente2 | 70 | 4 |

| Public Health, Community | 64 | 4 |

| Academic | 48 | 3 |

|

| ||

| Network Region3 | ||

| Western | 292 | 16 |

| Midwest | 180 | 10 |

| Southwest | 311 | 18 |

| South Central | 330 | 19 |

| South Atlantic | 327 | 18 |

| Northeast | 337 | 19 |

|

| ||

| Time Commitment | ||

| Full time | 1508 | 86 |

| Part time (<32 hrs) | 253 | 14 |

|

| ||

| Specialty Status | ||

| General Dentist | 1719 | 97 |

| Specialist | 56 | 3 |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 1451 | 82 |

| Black/African-American | 77 | 4 |

| Asian | 161 | 9 |

| Other | 70 | 4 |

|

| ||

| Patient Population Characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Private Insurance Status | ||

| <40% Private Insurance | 249 | 14 |

| 40–79% Private Insurance | 1017 | 58 |

| 80%+ Private Insurance | 476 | 27 |

|

| ||

| Patient Appointment Regularity | ||

| <50% of Patients Regularly Visit | 274 | 16 |

| 50–79% Regularly Visit | 1044 | 60 |

| 80%+ Regularly Visit | 428 | 25 |

Due to missing values, not all columns add to 100%.

Either HealthPartners Dental Group in greater Minneapolis, MN or Permanente Dental Associates in greater Portland, OR.

Reported on Enrollment Questionnaire as the state, subsequently categorized into one of the six regions of the network.

Dentists ranked the following crown indication factors the highest: Fractured or Cracked Tooth, Endodontic Therapy, and Broken Restorations. These were followed by Active Caries and Large Restoration. Responses are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Survey responses showing the leading reasons practitioners recommend crowns; how often practitioners recommend crowns for posterior teeth following endodontic therapy, and how often for anterior teeth

| Indications for Crowns: Responses (N=1,777) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Crown Indications | Mean Ranking1 (±SD) |

|

| |

| Fractured or Cracked Tooth | 1.8 (0.86) |

| Endodontic Therapy | 1.9 (0.79) |

| Broken Restoration | 1.9 (0.80) |

| Active Caries | 2.1 (0.84) |

| Large Restoration | 2.1 (0.79) |

| Change Vertical Dimension | 2.7 (0.53) |

| RPD Abutment | 2.7 (0.55) |

| Esthetics | 2.8 (0.52) |

|

| |

| Yes Response, Percent (n) | |

|

| |

| Posterior Endo | |

| Recommend Crown >75% | 94.1 (1671) |

| Recommend Crown 50–74% | 4.6 (82) |

| Recommend Crown 25–49% | 1.0 (18) |

| Recommend Crown <25% | 0.2 (4) |

|

| |

| Anterior Endo | |

| Recommend Crown >75% | 18.6 (331) |

| Recommend Crown 50–74% | 31.7 (562) |

| Recommend Crown 25–49% | 26.3 (466) |

| Recommend Crown <25% | 23.4 (416) |

When considering the ranking, a lower number indicates a condition which is more likely to prompt a recommendation for a crown. Range is 0–12.

As shown in Table 2, if a posterior tooth had been treated endodontically, practitioners were strongly in favor of recommending a crown, with 94% stating they would recommend a crown over 75% of the time. This percentage was lower when considering anterior teeth with endodontic treatment. The responses were evenly distributed, with about half of respondents recommending a crown over half the time.

Practitioners viewed photographs of posterior teeth with restorations (Fig. 1) and offered opinions of whether the tooth should receive a crown. These clinical photographs depicted teeth with a variety of restorations, from an occlusal alloy to a large MOD restoration. The responses to these questions from the survey are displayed in Table 3. In response to the occlusal alloy in Fig. 1A, 98% of respondents reported they would not likely or definitely not recommend a crown. The largest restoration, Fig. 1D, also produced a homogenous response, with 97% of practitioners reporting that they were very likely or likely to recommend a crown. The other restorations (Fig. 1B and 1C) produced more divergent responses.

Table 3.

Recommendations for crowns by practitioners responding to this survey. Photographs of posterior teeth with restorations are shown in Figure 1

| Recommendations for Crowns | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Figure 1A: Occlusal Restoration | Percent (n) |

|

| |

| Very likely to recommend a crown | 0.3 (6) |

| Likely to recommend a crown | 1.9 (33) |

| Not likely to recommend a crown | 32 (563) |

| Definitely not recommend a crown | 66 (1174) |

|

| |

| Figure 1B: DO Restoration | Percent (n) |

|

| |

| Very likely to recommend a crown | 12 (208) |

| Likely to recommend a crown | 36 (637) |

| Not likely to recommend a crown | 48 (843) |

| Definitely not recommend a crown | 5 (86) |

|

| |

| Figure 1C: MOD Restoration | Percent (n) |

|

| |

| Very likely to recommend a crown | 29 (513) |

| Likely to recommend a crown | 37 (657) |

| Not likely to recommend a crown | 30 (533) |

| Definitely not recommend a crown | 4 (73) |

|

| |

| Figure 1D: MOD with Fracture | Percent (n) |

|

| |

| Very likely to recommend a crown | 87 (1546) |

| Likely to recommend a crown | 10 (176) |

| Not likely to recommend a crown | 2 (41) |

| Definitely not recommend a crown | 1 (14) |

Among clinician and practice variables, neither clinician gender, race, specialty status, nor full-time commitment were significantly associated with the likelihood to recommend a crown based on the four restorations shown to practitioners in the questionnaire (Table 4). However, type of practice showed a significant association with CF, with practice owners and associates more likely than other groups to recommend a crown. Associates were more likely to recommend a crown than Permanente, Health Partners, or Academic clinicians. Practice Owners were more likely to recommend a crown than Academics or Health Partners clinicians. Public Health clinicians were more likely to recommend a crown than Academic and Health Partners clinicians. Permanente dentists were more likely to recommend a crown than Health Partners practitioners. Private insurance status was also significantly associated with the likelihood to recommend a crown. In practices where less than 40% of patients had private insurance, clinicians were significantly less likely to recommend a crown than practices that had 40–79% insurance coverage.

Table 4.

Dentist and practice factors associated with the likelihood of recommending a crown (Crown Factor)

| Characteristics | Number (n) | Crown Factor1 (SD) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1279 | 6.6 (1.8) | .36 |

| Female | 481 | 6.7 (1.8) | |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 1448 | 6.6 (1.9) | 0.41 |

| Black/African-American | 77 | 6.8 (1.7) | |

| Asian | 159 | 6.5 (1.7) | |

| Other | 70 | 6.9 (1.4) | |

|

| |||

| Type of Practice | |||

| Owner of Private Practice | 1291 | 6.8 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

| Associate in Private Practice | 207 | 6.9 (1.8) | |

| Health Partners | 43 | 5.0 (1.7) | |

| Permanente | 70 | 6.1 (1.5) | |

| Public Health, Community | 64 | 6.4 (1.7) | |

| Academic | 48 | 5.3 (1.7) | |

|

| |||

| Network Region | |||

| Western | 292 | 6.7 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

| Midwest | 179 | 6.3 (2.0) | |

| Southwest | 310 | 7.1 (1.8) | |

| South Central | 329 | 6.7 (1.9) | |

| South Atlantic | 326 | 6.7 (1.8) | |

| Northeast | 336 | 6.3 (1.8) | |

|

| |||

| Practice Busyness | |||

| Too busy | 101 | 6.1 (1.7) | 0.0002 |

| Burdened | 327 | 6.4 (1.9) | |

| Balanced | 908 | 6.8 (1.8) | |

| Not busy | 434 | 6.7 (1.9) | |

|

| |||

| Time ommitment | |||

| Full Time | 1504 | 6.7 (1.8) | 0.11 |

| Part Time (<32 hrs) | 252 | 6.5 (1.8) | |

|

| |||

| Private Insurance Status | |||

| <40% Private Insurance | 249 | 6.4 (2.0) | 0.02 |

| 40–79% Private Insurance | 1017 | 6.7 (1.8) | |

| 80%+ Private Insurance | 476 | 6.5 (1.8) | |

|

| |||

| Laboratory | |||

| Commercial | 1561 | 6.6 (1.8) | 0.0003 |

| In Office Traditional | 47 | 6.3 (1.9) | |

| In Office Milling | 163 | 7.2 (1.8) | |

|

| |||

| Optical Scanner Use | |||

| High: 75% or more | 146 | 7.2 (1.7) | 0.0006 |

| Less than 75% | 1626 | 6.6 (1.9) | |

Clinical photographs were used to calculate a “Crown Factor” (CF) number for practitioners responding to the survey. A higher number indicates a person is more likely to recommend a crown. Range is 0–12. The Crown Factor was associated with some clinician and practice variables. The CF value is listed ±Standard Deviation (SD).

Analysis of variance

Practitioners in the Midwest and Northeast were less likely to recommend crowns than practitioners from other parts of the country, while the highest crown factor was noted in the Southwest.

Perceived practice busyness was significantly associated with the likelihood to recommend a crown. Clinicians who reported a balanced practice load were more likely to recommend a crown than practitioners who were too busy to see all their patients or practitioners who felt burdened by their schedules. Practitioners who reported being not busy were more likely to recommend a crown than the ones who reported they were overly busy.

The use of optical scanners and in-office milling units was associated with a higher CF. Practitioners with an in-office milling unit were more likely to recommend a crown than either dentists using a commercial laboratory or an in-office laboratory. If clinicians use an optical scanner more than 75 percent of the time for crown impressions, they recommend a crown more often than people who use scanners less frequently or not at all (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

One clear area of consensus among dentists in this study is that crowns should be recommended when posterior teeth have had endodontic treatment. This recommendation is consistent with evidence from the literature. One study of over 1 million teeth showed a correlation between lack of coronal coverage in endodontically treated teeth and tooth fracture.22 Another study found the 5-year survival of endodontically treated molars without crowns was only 36 percent.23 An additional study found that molar survival without a crown is 50%, while survival increases to 98% with coronal coverage.24 A retrospective cohort analysis suggested that uncrowned endodontically treated teeth have a 6 times higher incidence of extraction than teeth with crowns; also, second molars were at higher risk than other teeth.25 The same benefit, however, is not always noted for anterior teeth in many of these studies.22–24, 26 Other factors influence tooth longevity for endodontically treated teeth, such as number of missing teeth and plaque control.27 In this sense, practitioners responding to this survey echo findings in the literature when making clinical decisions, as manifested by their frequently recommending crowns for posterior teeth treated endodontically, and sometimes recommending crowns for anterior teeth.

Broken cusps and fractured teeth were also reasons practitioners frequently cited to recommend crowns. The rate for coronal fractures is 89 per 1000 person years, with more fractures occurring in posterior teeth.28 Expressed another way, a dentist with 1000 patients in a practice might see 90 fractured teeth per year. One study found a lower estimate, at 20.5 per 1000 person years.29 The vast majority of these expose the dentin, and about half extend beyond the gingival crest of the dentinoenamel junction. Serious consequences (pulpal involvement or extraction) of these fractures range from 7–15 percent.30, 31 Fracture lines in the enamel of posterior teeth have also been recognized as a risk factor for tooth coronal fracture,3 where a tactilely detectable fracture line increased odds of fracture an astounding 75-fold. Given this evidence, and the incidence of reported tooth fractures, it seems reasonable that clinicians would recommend crowns when teeth are fractured or cracked.

Evidence in the literature supports crowning teeth with ‘large’ restorations to increase tooth longevity. One prospective cohort study examined over 40,000 patients for 3 months. In that time window, 238 fractures occurred. About 77 percent of the fractured teeth had restorations that involved 3 or more surfaces.29 Findings from other studies also suggest that larger restoration volume is associated with an increased fracture risk.1, 3, 11, 32, 33 Clinicians responding to this survey did list “Large Restoration” as a reason to recommend a crown, but not as highly as endodontic treatment or a cracked tooth. It should be noted that most clinicians will strongly consider patient preferences, expectations and other patient-centered factors when recommending crowns, in addition to the clinical findings. These types of patient factors were not explored in this survey. It is also fair to point out that crowns are generally profitable for a dental office, and finances may impact treatment recommendations. These issues were not directly addressed in the survey.

The response to the photographs of teeth with restorations proved interesting. There are limitations to this question, such as the fact that practitioners are looking at a two-dimensional photograph and therefore cannot examine the tooth clinically. Additionally, some practitioners might recommend an onlay or other restoration with cuspal coverage instead of a crown, and this was not provided as a response option. Nonetheless, the responses highlight the variability between practitioners when making treatment decisions. The MOD restoration in a premolar (Fig. 1C) produced the most divergent responses, with roughly one third of practitioners each responding very likely, likely, or not likely to recommend a crown. More agreement existed with the small occlusal restoration (Fig. 1A), where 98 percent of practitioners were either not likely or would definitely not recommend a crown. Conversely, when shown a large MOD amalgam and a fractured buccal cusp (Fig. 1D), 97 percent of practitioners endorsed “very likely” or “likely” to recommend a crown. It appears that more consensus exists regarding very large or small restorations, and great variation of treatment recommendations exists in the middle. Variables significantly associated with the likelihood to recommend a crown (CF) were Type of Practice, Network Region, Private Insurance Status, Practice Busyness, and Optical Scanner Use. To our knowledge, this is the first time that such associations have been reported. It is interesting to observe that factors unrelated to the tooth or patient may influence treatment recommendations. Practice owners and associates recommended crowns more than other clinicians. This could be due to financial incentives to provide crowns, or it could be that the solo practitioner believes that the crown has the highest rate of success, and wants to provide this treatment, regardless of cost to the patient. Practitioners in the Health Partners group had a low propensity to recommend crowns, which could reflect an emphasis on preventive dentistry pervasive in this group, or perhaps a lack of financial incentive for the clinician to provide a higher-cost treatment option. Additional variation may be due to different dentists having different opinions in any given clinical situation regarding the benefit of a crown. Private insurance status was significantly associated with the crown factor. This may reflect access to care issues or how patient preferences impact a practitioner recommendation. For example, if the clinician knows the patient has insurance coverage, he or she might recommend a crown more often.

It is unclear why the likelihood to recommend a crown varied by network region. This could be related to patient populations, or cultural differences, such as a belief in a “wait and see” attitude versus a “fix it before it breaks” attitude. Also, it should be recognized that practice type varies between regions, which might confound this variable. Practice Busyness was significantly associated with treatment recommendations. This factor has been shown to impact other aspects of clinical care, such as restoration longevity.34 Generally, the busier a clinician the less likely he/she is to recommend a crown. Presumably, this is because making a crown would take more time than other options, such as a direct restoration, and further burden the schedule.

As the use of digital imaging and milling becomes more prevalent, it was interesting to observe that frequent use of an optical scanner was associated with a higher propensity to recommend a crown. Similarly, in-office milling was associated with a significantly higher CF. Recognizing that many practitioners with an optical scanner will also utilize an in-office milling unit, the presence of this technology implies more recommendations for crowns. This could be due to the increased efficiency of providing this treatment (one appointment instead of two), higher patient demand for crowns, or these practitioners simply like doing crowns and are therefore more apt to have in-office milling and/or optical scanners.

This study does have certain limitations, and conclusions should take these into account. This study measured treatment recommendations using hypothetical clinical scenarios, which may differ from actual clinical treatment behavior. This study relied on questionnaire information rather than direct observation of procedures. Additionally, although the response rate was very good, it is possible that non-respondents would have reported different behavior. The questionnaire listed “broken restoration” as an indication for crowns, but did not provide “cracked tooth” as a specific response. The latter was a popular choice listed in the “other” category. It is possible that as an additional, specific category more clinicians would have selected this as a reason. The two-dimensional photographs used in the questionnaire could be interpreted in different ways, and this is a limitation of the study. Although network practitioners have much in common with dentists at large 35, 36 it may be that their crown procedures are not representative of a wider representation of dentists. Additionally, network members are not recruited randomly, so factors associated with network participation (e.g., an interest in clinical research) may make network dentists unrepresentative of dentists at large. While we cannot assert that network dentists are entirely representative, we can state that they have much in common with dentists at large, while also offering substantial diversity in these characteristics. This assertion is warranted because: 1) substantial percentages of network general dentists are represented in the various response categories of the characteristics in the Enrollment Questionnaire; 2) findings from several network studies document that network general dentists report patterns of diagnosis and treatment that are similar to patterns determined from non-network general dentists 37–39 and 3) the similarity of network dentists to non-network dentists using the best available national source, the 2010 ADA Survey of Dental Practice.40

In summary, it is clear that a complex interaction of factors can influence treatment recommendations. Dominant factors include items associated with tooth fracture, such as endodontic therapy, cracked or fractured teeth, and large restorations. Other factors are more subtle, and can be related to the clinician, such as where a practice is located, how busy it is, patient insurance status, or whether or not the practice utilizes in-office scanners. When making treatment decisions, clinicians should recognize that factors other than the patient or the tooth itself may influence their decisions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant U19-DE-22516. An Internet site devoted to details about the nation’s network is located at http://NationalDentalPBRN.org. We are very grateful to the network’s Regional Coordinators who followed-up with network practitioners to improve the response rate (Midwest Region: Tracy Shea, RDH, BSDH; Western Region: Stephanie Hodge, MA; Northeast Region: Christine O’Brien, RDH; South Atlantic Region: Hanna Knopf, BA, Deborah McEdward, RDH, BS, CCRP; South Central Region: Claudia Carcelén, MPH, Shermetria Massengale, MPH, CHES, Ellen Sowell, BA; Southwest Region: Stephanie Reyes, BA, Meredith Buchberg, MPH, Colleen Dolan, MPH). Opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as necessarily representing the views of the respective organizations or the National Institutes of Health. The informed consent of all human subjects who participated in this investigation was obtained after the nature of the procedures had been explained fully.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CF

crown factor

- PBRN

practice-based research network

- NIDCR

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

- RPD

removable partial denture

- SD

standard deviation

APPENDIX

[Note to reviewers: The purpose of this appendix is to make certain information directly accessible to the reviewers in a single document. This Appendix will not appear in the published version of the manuscript. The typical reader will have access to this Appendix via http://nationaldentalpbrn.org/study-results.php, “Factors for Successful Crowns” section.]

Table A1.

Regarding the various restorations shown in Fig 1, numbers (row percent1) of respondents by category and their likelihood to recommend a crown

| Characteristic | Very Likely to Recommend Crown | Likely to Recommend Crown | Not Likely to Recommend Crown | Definitely Not Recommend Crown | Total | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Figure 1A, an occlusal restoration | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 5 (0.4) | 24 (2) | 388 (30) | 865 (67) | 1282 | 0.23 |

| Female | 1 (0.2) | 9 (2) | 170 (35) | 302 (63) | 482 | |

| Total | 6 | 33 | 558 | 1167 | 1764 | |

|

| ||||||

| Years Since Dental School Graduation | 0.72 | |||||

| <10 | 1 (0.3) | 6 (2) | 91 (31) | 194 (66) | 292 | |

| 10–19 | 1 (0.3) | 9 (2) | 132 (36) | 225 (61) | 367 | |

| 20–29 | 2 (0.5) | 6 (2) | 120 (31) | 253 (66) | 381 | |

| 30+ | 2 (0.3) | 12 (2) | 220 (30) | 499 (68) | 733 | |

| Total | 6 | 33 | 563 | 1171 | 1773 | |

|

| ||||||

| Type of Practice | ||||||

| Owner of Private Practice | 5 (0.4) | 23 (2) | 433 (33) | 833 (64) | 1294 | 0.0009 |

| Associate in Priv. Practice | 0 | 6 (3) | 76 (37) | 125 (60) | 207 | |

| Health Partners2 | 0 | 0 | 6 (14) | 38 (86) | 44 | |

| Permanente2 | 0 | 0 | 17 (24) | 53 (76) | 70 | |

| Other Managed Care | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 | 9 (90) | 10 | |

| Public Health, Community | 0 | 2 (3) | 17 (27) | 45 (70) | 64 | |

| Federal Government | 0 | 0 | 5 (21) | 19 (79) | 24 | |

| Academic | 1 (2) | 0 | 4 (8) | 43 (90) | 48 | |

| Total | 6 | 32 | 558 | 1165 | 1761 | |

|

| ||||||

| Network Region3 | ||||||

| Western | 0 | 6 (2) | 90 (31) | 196 (67) | 292 | 0.04 |

| Midwest | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1) | 51 (28) | 126 (70) | 180 | |

| Southwest | 0 | 9 (3) | 120 (39) | 181 (58) | 310 | |

| South Central | 3 (2) | 6 (2) | 112 (34) | 209 (63) | 330 | |

| South Atlantic | 1 (0.3) | 7 (2) | 103 (32) | 216 (66) | 327 | |

| Northeast | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.9) | 87 (26) | 246 (73) | 337 | |

| Total | 6 | 33 | 563 | 1174 | 1776 | |

|

| ||||||

| Time Commitment | ||||||

| Full time | 4 (0.3) | 30 (2) | 484 (32) | 989 (66) | 1507 | 0.11 |

| Part time (<32 hrs) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 74 (29) | 176 (70) | 253 | |

| Total | 6 | 31 | 558 | 1165 | 1760 | |

|

| ||||||

| Specialty Status | ||||||

| General Dentist | 6 (0.3) | 32 (2) | 551 (32) | 1129 (66) | 1718 | 0.37 |

| Specialist | 0 | 1 (2) | 12 (21) | 43 (77) | 56 | |

| Total | 6 | 33 | 563 | 1172 | 1774 | |

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 6 (0.4) | 29 (2) | 461 (32) | 955 (66) | 1451 | 0.91 |

| Black/African-American | 0 | 1 (1) | 21 (27) | 55 (71) | 77 | |

| Asian | 0 | 3 (2) | 48 (30) | 109 (68) | 160 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 24 (34) | 46 (66) | 70 | |

| Total | 6 | 33 | 554 | 1165 | 1758 | |

|

| ||||||

| Figure 1B, a DO alloy | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 148 (12) | 463 (36) | 602 (47) | 67 (5) | 1280 | 0.51 |

| Female | 57 (12) | 168 (35) | 239 (50) | 18 (4) | 482 | |

| Total | 205 | 631 | 841 | 85 | 1762 | |

|

| ||||||

| Years Since Dental School Graduation | 0.20 | |||||

| <10 | 28 (10) | 101 (35) | 151 (52) | 11 (4) | 291 | |

| 10–19 | 39 (11) | 132 (36) | 185 (50) | 11 (3) | 367 | |

| 20–29 | 51 (13) | 129 (34) | 180 (47) | 22 (6) | 382 | |

| 30+ | 90 (12) | 275 (38) | 324 (44) | 42 (6) | 731 | |

| Total | 208 | 637 | 840 | 86 | 1771 | |

|

| ||||||

| Type of Practice | ||||||

| Owner of Private Practice | 167 (13) | 479 (37) | 592 (46) | 55 (4) | 1293 | <0.0001 |

| Associate in Priv. Practice | 30 (14) | 85 (41) | 85 (41) | 7 (3) | 207 | |

| Health Partners2 | 0 | 10 (23) | 27 (63) | 6 (14) | 43 | |

| Permanente2 | 1 (1) | 22 (31) | 43 (61) | 4 (6) | 70 | |

| Other Managed Care | 1 (10) | 2 (20) | 4 (40) | 3 (30) | 10 | |

| Public Health, Community | 4 (0.2) | 16 (1) | 40 (2) | 4 (0.2) | 64 | |

| Federal Government | 3 (12) | 8 (33) | 13 (54) | 0 | 24 | |

| Academic | 0 | 9 (19) | 32 (67) | 7 (16) | 48 | |

| Total | 206 | 631 | 836 | 86 | 1759 | |

|

| ||||||

| Network Region3 | ||||||

| Western | 37 (13) | 98 (34) | 145 (50) | 12 (4) | 292 | 0.0005 |

| Midwest | 16 (9) | 54 (30) | 96 (54) | 13 (7) | 179 | |

| Southwest | 51 (16) | 128 (41) | 124 (40) | 8 (3) | 311 | |

| South Central | 42 (13) | 127 (38) | 146 (42) | 15 (5) | 330 | |

| South Atlantic | 37 (11) | 125 (38) | 150 (46) | 14 (4) | 326 | |

| Northeast | 25 (7) | 105 (31) | 182 (54) | 24 (7) | 336 | |

| Total | 208 | 637 | 843 | 86 | 1774 | |

|

| ||||||

| Time Commitment | ||||||

| Full time | 177 (12) | 548 (36) | 709 (47) | 72 (5) | 1506 | 0.73 |

| Part time (<32 hrs) | 27 (11) | 85 (34) | 126 (50) | 14 (6) | 252 | |

| Total | 204 | 633 | 835 | 86 | 1758 | |

|

| ||||||

| Specialty Status | ||||||

| General Dentist | 205 (12) | 619 (36) | 810 (47) | 82 (5) | 1716 | 0.31 |

| Specialist | 3 (5) | 18 (32) | 31 (55) | 4 (7) | 56 | |

| Total | 208 | 637 | 841 | 86 | 1772 | |

|

| ||||||

| Race | 0.08 | |||||

| White | 176 (12) | 520 (36) | 678 (47) | 75 (5) | 1449 | |

| Black/African-American | 10 (13) | 32 (42) | 32 (42) | 3 (4) | 77 | |

| Asian | 16 (10) | 45 (28) | 92 (58) | 7 (4) | 160 | |

| Other | 6 (9) | 33 (47) | 31 (44) | 0 | 70 | |

| Total | 208 | 630 | 833 | 85 | 1756 | |

|

| ||||||

| Figure 1C, an MOD restoration | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 369 (29) | 457 (36) | 395 (31) | 60 (5) | 1281 | 0.06 |

| Female | 139 (29) | 196 (41) | 136 (28) | 12 (2) | 483 | |

| Total | 508 | 653 | 531 | 72 | 1764 | |

|

| ||||||

| Years Since Dental School Graduation | 0.001 | |||||

| <10 | 68 (23) | 120 (41) | 97 (33) | 7 (2) | 292 | |

| 10–19 | 114 (31) | 153 (42) | 93 (25) | 7 (2) | 367 | |

| 20–29 | 126 (33) | 132 (35) | 105 (27) | 19 (5) | 382 | |

| 30+ | 204 (28) | 252 (34) | 236 (32) | 40 (5) | 732 | |

| Total | 512 | 657 | 531 | 73 | 1773 | |

|

| ||||||

| Type of Practice | ||||||

| Owner of Private Practice | 408 (32) | 466 (36) | 366 (28) | 54 (4) | 1294 | <0.0001 |

| Associate in Priv. Practice | 60 (29) | 90 (43) | 53 (26) | 4 (2) | 207 | |

| Health Partners2 | 1 (2) | 15 (34) | 24 (55) | 4 (9) | 44 | |

| Permanente2 | 9 (13) | 36 (51) | 23 (33) | 2 (3) | 70 | |

| Other Managed Care | 1 (10) | 3 (30) | 5 (50) | 1 (10) | 10 | |

| Public Health, Community | 22 (34) | 18 (28) | 22 (34) | 2 (3) | 64 | |

| Federal Government | 1 (4) | 8 (33) | 14 (58) | 1 (4) | 24 | |

| Academic | 4 (8) | 17 (35) | 22 (46) | 5 (10) | 48 | |

| Total | 506 | 653 | 529 | 73 | 1761 | |

|

| ||||||

| Network Region3 | ||||||

| Western | 75 (26) | 126 (43) | 83 (28) | 8 (3) | 292 | 0.0008 |

| Midwest | 41 (23) | 61 (34) | 70 (39) | 8 (4) | 180 | |

| Southwest | 120 (39) | 105 (34) | 79 (25) | 7 (2) | 311 | |

| South Central | 104 (32) | 113 (34) | 96 (28) | 16 (5) | 329 | |

| South Atlantic | 92 (28) | 128 (39) | 93 (28) | 14 (4) | 327 | |

| Northeast | 81 (24) | 124 (37) | 112 (33) | 20 (6) | 337 | |

| Total | 513 | 657 | 533 | 73 | 1776 | |

|

| ||||||

| Time Commitment | ||||||

| Full time | 438 (29) | 562 (37) | 449 (30) | 58 (4) | 1507 | 0.39 |

| Part time (<32 hrs) | 68 (27) | 90 (36) | 80 (32) | 15 (6) | 253 | |

| Total | 506 | 652 | 529 | 73 | 1760 | |

|

| ||||||

| Specialty Status | ||||||

| General Dentist | 498 (29) | 642 (37) | 507 (30) | 71 (4) | 1718 | 0.17 |

| Specialist | 15 (27) | 15 (27) | 24 (43) | 56 (4) | 56 | |

| Total | 513 | 657 | 531 | 73 | 1774 | |

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 413 (28) | 528 (36) | 444 (31) | 65 (4) | 1450 | 0.12 |

| Black/African-American | 30 (39) | 23 (30) | 23 (30) | 1 (1) | 77 | |

| Asian | 45 (28) | 69 (43) | 40 (25) | 7 (4) | 161 | |

| Other | 21 (30) | 32 (46) | 17 (24) | 0 | 70 | |

| Total | 509 | 652 | 524 | 73 | 1758 | |

|

| ||||||

| Figure 1D, an MOD alloy with a broken cusp | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1129 (88) | 113 (9) | 28 (2) | 12 (1) | 1282 | 0.047 |

| Female | 406 (84) | 62 (13) | 13 (3) | 2 (0.4) | 483 | |

| Total | 1535 | 175 | 41 | 14 | 1765 | |

|

| ||||||

| Years Since Dental School Graduation | 0.20 | |||||

| <10 | 249 (85) | 36 (12) | 5 (2) | 2 (0.7) | 292 | |

| 10–19 | 320 (87) | 38 (10) | 7 (2) | 2 (0.6) | 367 | |

| 20–29 | 319 (84) | 45 (12) | 14 (4) | 4 (1) | 382 | |

| 30+ | 655 (90) | 57 (8) | 15 (2) | 6 (0.8) | 733 | |

| Total | 1543 | 176 | 41 | 14 | 1774 | |

|

| ||||||

| Type of Practice | ||||||

| Owner of Private Practice | 1144 (88) | 110 (8) | 30 (2) | 11 (0.9) | 1295 | <0.0001 |

| Associate in Priv. Practice | 182 (88) | 19 (9) | 5 (2) | 1 (0.4) | 207 | |

| Health Partners2 | 25 (57) | 15 (34) | 4 (9) | 0 | 44 | |

| Permanente2 | 61 (87) | 7 (10) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 70 | |

| Other Managed Care | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| Public Health, Community | 55 (86) | 8 (13) | 1 (2) | 0 | 64 | |

| Federal Government | 21 (88) | 3 (13) | 0 | 0 | 24 | |

| Academic | 37 (77) | 10 (21) | 0 | 1 (2) | 48 | |

| Total | 1532 | 175 | 41 | 14 | 1762 | |

|

| ||||||

| Network Region3 | ||||||

| Western | 260 (89) | 26 (9) | 5 (2) | 1 (0.3) | 292 | 0.25 |

| Midwest | 148 (82) | 25 (14) | 5 (3) | 2 (1) | 180 | |

| Southwest | 275 (88) | 26 (8) | 8 (3) | 2 (0.6) | 311 | |

| South Central | 283 (86) | 36 (11) | 9 (3) | 2 (0.6) | 330 | |

| South Atlantic | 297 (91) | 19 (6) | 8 (2) | 3 (0.9) | 327 | |

| Northeast | 283 (84) | 44 (13) | 6 (2) | 4 (1) | 337 | |

| Total | 1546 | 176 | 41 | 14 | 1777 | |

|

| ||||||

| Time Commitment | ||||||

| Full time | 1313 (87) | 147 (10) | 36 (2) | 12 (0.8) | 1508 | 0.84 |

| Part time (<32 hrs) | 217 (86) | 29 (11) | 5 (2) | 2 (0.8) | 253 | |

| Total | 1530 | 176 | 41 | 14 | 1761 | |

|

| ||||||

| Specialty Status | ||||||

| General Dentist | 1503 (87) | 166 (10) | 37 (2) | 13 (0.8) | 1719 | 0.02 |

| Specialist | 42 (75) | 9 (16) | 4 (7) | 1 (2) | 56 | |

| Total | 1545 | 175 | 41 | 14 | 1775 | |

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1264 (87) | 140 (10) | 36 (2) | 11 (0.7) | 1451 | 0.84 |

| Black/African-American | 67 (87) | 9 (12) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 77 | |

| Asian | 138 (86) | 18 (11) | 4 (2) | 1 (0.6) | 70 | |

| Other | 64 (91) | 4 (6) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 161 | |

| Total | 1533 | 171 | 41 | 14 | 1759 | |

Due to missing values, not all rows add to 100%, and not all totals sum to 1,777.

Either HealthPartners Dental Group in greater Minneapolis, MN or Permanente Dental Associates in greater Portland, OR.

Reported on Enrollment Questionnaire as the state, subsequently categorized into one of the six regions of the network.

Footnotes

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bader JD, Shugars DA. Summary review of the survival of single crowns. Gen Dent. 2009;57(1):74–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bader JD, Shugars DA, Roberson TM. Using crowns to prevent tooth fracture. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24(1):47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bader JD, Shugars DA, Martin JA. Risk indicators for posterior tooth fracture. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135(7):883–92. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez E, Martin J, Vildosola P, et al. Can repair increase the longevity of composite resins? Results of a 10-year clinical trial. J Dent. 2015;43(2):279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordan VV, Riley J, 3rd, Geraldeli S, et al. The decision to repair or replace a defective restoration is affected by who placed the original restoration: findings from the National Dental PBRN. J Dent. 2014;42(12):1528–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moncada G, Vildosola P, Fernandez E, et al. Longitudinal results of a 10-year clinical trial of repair of amalgam restorations. Oper Dent. 2015;40(1):34–43. doi: 10.2341/14-045-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gowda D, Lamster IB. The diagnostic process. Dent Clin North Am. 2011;55(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omar R, Akeel R. Prosthodontic decision-making: what unprompted information do dentists seek before prescribing treatment? J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(1):69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koka S, Eckert SE, Choi YG, Montori VM. Clinical decision-making practices among a subset of North American prosthodontists. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20(6):606–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bader JD, Shugars DA. Variation in dentists’ clinical decisions. J Public Health Dent. 1995;55(3):181–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1995.tb02364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolker JL, Damiano PC, Flach SD, et al. The cost-effectiveness of large amalgam and crown restorations over a 10-year period. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66(1):57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2006.tb02552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maryniuk GA, Schweitzer SO, Braun RJ. Replacement of amalgams with crowns: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1988;16(5):263–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1988.tb01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalsi JS, Hemmings K. The influence of patients’ decisions on treatment planning in restorative dentistry. Dent Update. 2013;40(9):698–700. 02–4, 07–8, 10. doi: 10.12968/denu.2013.40.9.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bader JD, Shugars DA. Descriptive models of restorative treatment decisions. J Public Health Dent. 1998;58(3):210–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1998.tb02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bader JD, Shugars DA. Understanding dentists’ restorative treatment decisions. J Public Health Dent. 1992;52(2):102–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1992.tb02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan DS, Spencer AJ. The role of dentist, practice and patient factors in the provision of dental services. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(3):181–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Korelitz JJ, et al. Purpose, structure, and function of the United States National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Dent. 2013;41(11):1051–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network tnsnAahno. [Accessed May 15 2015]; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert GH, Richman JS, Gordan VV, et al. Lessons learned during the conduct of clinical studies in the dental PBRN. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(4):453–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Study FDC Florida Dental Care Study. [Accessed July 1 2015]; “ http://nersp.nerdc.ufl.edu/~gilbert/”.

- 21.Funkhouser E, Fellows JL, Gordan VV, et al. Supplementing online surveys with a mailed option to reduce bias and improve response rate: the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Public Health Dent. 2014;74(4):276–82. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salehrabi R, Rotstein I. Endodontic treatment outcomes in a large patient population in the USA: an epidemiological study. J Endod. 2004;30(12):846–50. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000145031.04236.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagasiri R, Chitmongkolsuk S. Long-term survival of endodontically treated molars without crown coverage: a retrospective cohort study. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;93(2):164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorensen JA, Martinoff JT. Intracoronal reinforcement and coronal coverage: a study of endodontically treated teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;51(6):780–4. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(84)90376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aquilino SA, Caplan DJ. Relationship between crown placement and the survival of endodontically treated teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87(3):256–63. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2002.122014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodacre CJ, Spolnik KJ. The prosthodontic management of endodontically treated teeth: a literature review. Part I. Success and failure data, treatment concepts. J Prosthodont. 1994;3(4):243–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849x.1994.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caplan DJ, Weintraub JA. Factors related to loss of root canal filled teeth. J Public Health Dent. 1997;57(1):31–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1997.tb02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bader JD, Martin JA, Shugars DA. Incidence rates for complete cusp fracture. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29(5):346–53. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fennis WM, Kuijs RH, Kreulen CM, et al. A survey of cusp fractures in a population of general dental practices. Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15(6):559–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bader JD, Martin JA, Shugars DA. Preliminary estimates of the incidence and consequences of tooth fracture. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126(12):1650–4. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bader JD, Shugars DA, Sturdevant JR. Consequences of posterior cusp fracture. Gen Dent. 2004;52(2):128–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolker JL, Damiano PC, Armstrong SR, et al. Natural history of treatment outcomes for teeth with large amalgam and crown restorations. Oper Dent. 2004;29(6):614–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolker JL, Damiano PC, Jones MP, et al. The timing of subsequent treatment for teeth restored with large amalgams and crowns: factors related to the need for subsequent treatment. J Dent Res. 2004;83(11):854–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCracken MS, Gordan VV, Litaker MS, et al. A 24-month evaluation of amalgam and resin-based composite restorations: Findings from The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(6):583–93. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, et al. Practices participating in a dental PBRN have substantial and advantageous diversity even though as a group they have much in common with dentists at large. BMC Oral Health. 2009;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, et al. Dentists in practice-based research networks have much in common with dentists at large: evidence from the Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Gen Dent. 2009;57(3):270–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordan VV, Garvan CW, Heft MW, et al. Restorative treatment thresholds for interproximal primary caries based on radiographic images: findings from the Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Gen Dent. 2009;57(6):654–63. quiz 64–6, 595, 680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gordan VV, Garvan CW, Richman JS, et al. How dentists diagnose and treat defective restorations: evidence from the dental practice-based research network. Oper Dent. 2009;34(6):664–73. doi: 10.2341/08-131-C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norton WE, Funkhouser E, Makhija SK, et al. Concordance between clinical practice and published evidence: findings from The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(1):22–31. doi: 10.14219/jada.2013.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Dental Association Survey Center. The 2010 Survey of Dental Practice. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]