Abstract

Background

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR, neutrophil count divided by lymphocyte count) is a marker of inflammation associated with poor cancer outcomes. The role of NLR in borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (BRPC) is unknown. We hypothesized that increased NLR in patients with BRPC following neoadjuvant therapy is inversely associated with survival.

Methods

Patients from our BRPC database were identified who completed neoadjuvant therapy and underwent resection. The NLR difference was calculated as the NLR after neoadjuvant therapy minus the NLR before neoadjuvant therapy. Patients were assigned to the increased NLR cohort if the difference was ≥2.5 units; all others were assigned to the stable NLR cohort. Statistical analyses were performed with t-test and regression.

Results

Of 62 patients identified, 43 patients were assigned to the stable NLR cohort and 19 patients to the increased NLR cohort. There were no differences in stage, age, or gender. The pre-neoadjuvant NLR was 3.1±2.4, whereas the post-neoadjuvant NLR was 4.4±3.5 (P=0.002). Overall survival was significantly worse in the increased NLR cohort compared with the stable NLR cohort (P=0.009) with a Cox hazard ratio (HR) of 2.9 (P=0.02). N0 disease conferred a survival advantage over N1 disease (Cox HR=0.3, P=0.01). On multivariate Cox hazard regression analysis, both increased NLR and N1 stage were associated with worse survival (P<0.01).

Conclusions

This is the first investigation demonstrating an independent, inverse association between survival and decreased NLR in patients with BRPC. These findings support exploring predictive inflammatory biomarkers, such as NLR, to investigate inflammation and improve outcomes.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, borderline resectable, multidisciplinary management, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio, inflammation

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains one of the deadliest malignances, with an increasing incidence worldwide over the past few decades.1 Surgical outcomes for PDAC remain dismal (5-year survival rate of 10%-30%) and have not improved in decades. Biomarkers to predict outcomes or agents that target processes that lead to PDAC aggressiveness is a high research priority.

Inflammation is a well-established hallmark of cancer.2 For example, numerous data have linked the development of inflammation with carcinogenesis.3,4 Furthermore, blocking inflammation with anti-inflammatory drugs improves outcomes in multiple types of cancers.5, 6 Likewise, low levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein are associated with increased survival in PDAC.7 However, there remains a gap regarding the precise role of inflammation in PDAC and how to accurately measure it in this patient population.

Multiple surrogate assays have been used to measure inflammation. For example, the serum neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has been utilized to measure inflammation since neutrophils release mediators of inflammation. NLR is calculated from the results of the standard laboratory complete blood cell count. The NLR is a marker for systemic inflammation and has been studied as a prognostic factor in numerous cancers.8–10 In general, an NLR value greater than 4 is associated with systemic inflammation.11 The ratio of normal to high NLR is about 2 in one meta-analysis investigating NLR in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients with an accepted NLR of 4 identifying systemic inflammation.12

Previous work has investigated systemic inflammation in resected and metastatic PDAC. In most instances, those studies demonstrated worse survival with increased levels of inflammation.13, 14 However, the subset of patients with PDAC who are classified as borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (BRPC) have not been reported. BRPC patients have PDAC with limited involvement of blood vessels and usually undergo neoadjuvant therapy before resection. Patients with BRPC undergo treatment with neoadjuvant therapy in a multimodality fashion in order to limit futile operations and minimize morbidity that is unlikely to benefit the patient.15 Although protocols vary, patients with BRPC receive systemic chemotherapy for 3 months, with some institutions utilizing radiotherapy thereafter.16, 17 No studies in the literature have investigated changes in NLR in patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy for BRPC.

We hypothesized that increased NLR in patients with BRPC following neoadjuvant therapy would be inversely associated with overall survival.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Eligible patients with BRPC (2006-2013) were identified from the Moffitt Cancer Center prospective health and research informatics data warehouse. Inclusion criteria included diagnosis of PDAC, staged as BRPC, completion of neoadjuvant therapy, and underwent curative resection. Our institutional protocol identified patients as borderline resectable based on the most recent NCCN guidelines at the time of diagnosis utilizing both CT scan and endoscopic ultrasound. Patients deemed medically unfit for surgery were excluded. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy usually consisted of gemcitabine, docetaxel, and capecitabine for 3 months, with neoadjuvant radiotherapy usually started 1 week after completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Radiation consisted of stereotactic body radiotherapy daily for 5 days or intensity-modulated radiotherapy 5 days per week for 6 weeks.

NLR

The NLR was calculated by dividing the absolute neutrophil count by the lymphocyte count as part of the complete blood cell count. The difference in NLR was calculated as the NLR after completion of neoadjuvant therapy minus the NLR before neoadjuvant therapy. The value closest to initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy was used for the pre-neoadjuvant NLR value while the NLR values closest to the completion of radiotherapy was used for the post-neoadjuvant value. Because the mean pre-neoadjuvant NLR was 3.1 with a standard deviation of 2.4, a clinically significant increase in NLR (increased NLR cohort) was defined as an increase of more than 2.4 units. Patients with differences less than or equal to 2.4 units (including negative differences) were classified as stable NLR.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was set to α = 0.05. Survival was investigated with the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. Comparisons between the NLR cohorts were made with the paired t-test or Wilcoxan rank sum test (for non-normal data). Survival hazards and binary outcomes were investigated with Cox proportional hazard regression and multivariate logistic regression, respectively.

Results

NLR values in patients with BRPC

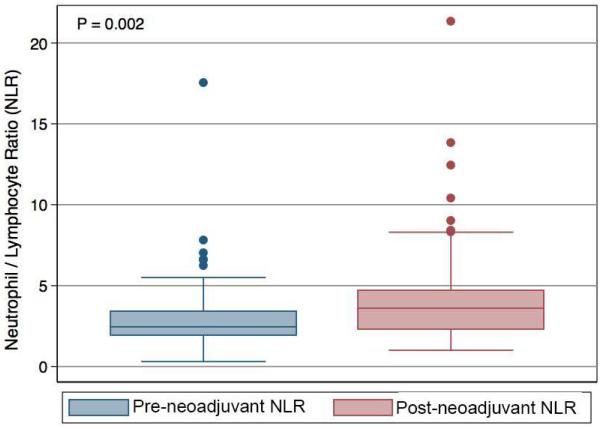

We identified 62 patients in our database who were eligible for our study: 42 patients were classified as borderline resectable based on venous involvement, and 20 patients were classified as borderline resectable based on arterial involvement. The mean age was 65.6 ± 9.0 years, 60% were male patients, and 97% of patients had R0 resections of their tumor. The mean pre-neoadjuvant NLR was 3.1 ± 2.4, and the mean post-neoadjuvant NLR was 4.4 ± 3.5 (P = 0.002) for the entire group (Figure 1). Of 62 patients, 19 patients were assigned to the increased NLR cohort and 43 patients were assigned to the stable NLR cohort. In the increased NLR cohort, the NLR results before and after neoadjuvant therapy were 3.2 ± 3.6 and 8.2 ± 4.9, respectively (Table I; P = 0.001). In the stable NLR group, the NLR results before and after neoadjuvant therapy were 3.0 ± 1.7 and 3.2 ±1.8, respectively (Table I; P = 0.14). There were no significant differences in gender, tumor location, tumor stage, performance status, or Ca19-9 levels (Table I) between the two groups. Patients in the increased NLR cohort were slightly younger, but this did not reach statistical significance (Table I). Finally, changes in Ca19-9 levels after neoadjuvant therapy compared to pre-neoadjuvant therapy were not significantly different between the NLR cohorts (P = 0.64).

Figure 1.

Box plot representing the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) before (A) and after (B) neoadjuvant therapy for resected patients (P = 0.002). Boxes represent the interquartile range, whereas the solid line in each box represents the median.

Table I.

Characteristics of resected patients in the increased NLR and stable NLR cohorts

| Characteristic | Increased NLR (n = 19) |

Stable NLR (n = 43) |

P

Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 62 ± 11 | 67 ± 8 | 0.0.099 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 12 (63%) | 25 (58%) | 0.71 |

| Pathologic stage, n (%) | |||

| T0 | 2 (11%) | 5 (11%) | 0.0.60 |

| T1-2 | 7 (37%) | 11 (26%) | |

| T3 | 10 (52%) | 27 (63%) | |

| T4 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| N0 | 13 (68%) | 28 (65%) | 0.80 |

| N1 | 6 (32%) | 15 (35%) | |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 18 (95%) | 34 (79%) | 0.13 |

| 1 | 1 (5%) | 9 (21%) | |

| Tumor location, n (%) | |||

| Head | 8 (42%) | 33 (77%) | 0.64 |

| Uncinate | 6 (32%) | 3 (7%) | |

| Neck | 3 (16%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Body/tail | 2 (10%) | 6 (14%) | |

| Pre-treatment CA 19-9 (mean ± SD, U/mL) |

2412 ± 4744 | 1193 ± 2189 | 0..75 |

| Type of neoadjuvant radiotherapy, n (%) |

|||

| SBRT | 11 (61%) | 35 (81%) | 0.1 |

| IMRT | 7(39%) | 8 (19%) | |

| Pre-neoadjuvant NLR (mean ± SD) | 3.2 ± 3.6 | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 0.20 |

| Post-neoadjuvant NLR (mean ± SD) |

8.2 ± 4.9 | 3.2 ± 1.8 | <0.0001 |

| Change in NLR (mean ± SD) | 6.0 ± 4.7 | 0.1 ± 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| R0 margins, n (%) | 19 (100%) | 41 (95%) | 1 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) |

8 (62%) | 19 (56%) | 0.73 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 9 (47%) | 31 (72%) | 0.06 |

IMRT, intensity-modulated radiotherapy; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; SBRT, stereotactic body radiotherapy

Increased NLR after neoadjuvant therapy is associated with poor prognosis in BRPC

Overall survival was significantly shorter in the increased NLR cohort compared with the stable NLR cohort (Figure 2; P = 0.009) with a Cox hazard ratio of 2.9 (P = 0.02). Pre-neoadjuvant NLR by itself was not associated with survival in patients with BRPC (P = 0.09). Likewise, post-neoadjuvant NLR was not associated with survival in patients with BRPC (P = 0.14). Increased NLR was associated with worse overall survival on univariate Cox hazard regression (P = 0.01).

Figure 2.

Resected patients with clinically significant rises in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (increased NLR) had shorter median overall survival (24 vs. 40 months) on Kaplan-Meier analysis (log-rank P = 0.009) compared with patients without rises in the NLR (stable NLR). The Cox proportional hazard ratio is 2.6 (P = 0.01).

Survival is associated with nodal stage but not tumor stage

Survival was not associated with AJCC tumor stage (Table II), but N0 disease was associated with improved survival compared with N1 disease (Cox hazard ratio = 0.3, P = 0.01). Variables with P < 0.2 on univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model (Table II). On multivariate Cox regression analysis, both increased NLR and N1 stage remained independent predictors of worse survival (multivariate P < 0.01 for both).

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate Cox hazard regression analysis for overall survival of resected patients

| Characteristic | Univariate Cox HR |

P

Value |

Multivariate Cox HR |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | 0.95 | ||

| Male gender | 1.7 | 0.21 | ||

| Pathologic stage | 1.2 | 0.38 | ||

| ECOG performance status | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.6 | 0.49 |

| Tumor location (compared with head tumor) |

0.45 | 0.48 | ||

| Pre-treatment CA 19-9 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Neoadjuvant SBRT | 0.6 | 0.24 | ||

| R0 margins | n/a | |||

| T stage | 1.2 | 0.37 | ||

| N stage | 3.2 | 0.01 | 3.2 | 0.01 |

| Postoperative complications | 1.2 | 0.67 | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.7 | 0.36 | ||

| Increased NLR | 2.8 | 0.01 | 3.0 | 0.01 |

Univariate variables with P < 0.2 were included in the multivariate model.

NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; SBRT, stereotactic body radiotherapy.

Patients in the stable NLR cohort without nodal disease (N0) after final resection had the longest overall survival, but N0 patients with increased NLR did as poorly as patients with N1 disease in the stable NLR cohort (Figure 3; P = 0.001). In addition, patients with increased NLR and N1 disease had the lowest overall median survival (P = 0.003). Finally, the variables NLR and nodal stage (N stage) remained independently associated with survival (Table II) and statistically independent (P > 0.8).

Figure 3.

Resected patients with rises in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (increased NLR) and no nodal disease (N0) have long-term survival as poor as those with nodal spread (N1 disease) when analyzed in the Kaplan-Meier method. Those patients with nodal disease (N1) and rises in the NLR (Increased NLR) had the lowest overall and median survival (log rank P = 0.001).

Discussion

Interestingly, we found that an increase in systemic inflammation as measured by NLR was associated with decreased survival. Neither NLR before neoadjuvant therapy nor NLR after neoadjuvant therapy was alone associated with survival. We speculated that the activation of an inflammatory milieu after treatment results in worse outcomes, and theorize that cancer cell death results in an immune response and subsequent inflammation. Changes in the NLR are a biomarker of this tumor biology, and this may worsen the other hallmarks of cancer.

Prolonged inflammation plays a critical role in the carcinogenesis of PDAC and prognosis of patients.18–21 Szkandera et al demonstrated that systemic inflammation, as measured by NLR, is a prognostic factor and is associated with worse overall survival in patients with metastatic PDAC.22 Importantly, our study is the first to demonstrate that inflammatory changes after neoadjuvant therapy is associated with survival. Likewise, this is the first analysis investigating systemic inflammation in patients with BRPC.

Inflammation has been demonstrated to be a marker for poor survival in many other cancers such as colorectal carcinoma and gastric cancer.12, 23, 24 However, no group has described changes in the NLR due to therapy in PDAC or any other gastrointestinal malignancies. Guthrie et al.25 demonstrated limited utility of NLR compared with other prognostic models in postoperative patients with colorectal cancer but did not investigate changes in NLR. In that series, it appears that the marker may have been utilized too late in treatment to provide meaningful information on survival. Similar to our work, Lorente et al.26 found that changes in NLR were associated with survival for patients with prostate cancer on second-line chemotherapy, but this analysis occurred late in the patients’ treatment course. Importantly, this is consistent with our results.

We investigated clinicopathologic differences between the 2 cohorts and found no significant differences except for post-neoadjuvant NLR changes (Table I). In BRPC, adjuvant therapy is not standardized. It is well known that many patients do not receive adjuvant chemotherapy due to poor recovery after pancreatic resection, especially pancreticoduodenectomy.27, 28 We found a small, non-significant increase in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy in the stable NLR cohort (Table I), and this was not associated with survival (Table II).

Interestingly, we did not identify an association between post-operative complications and overall survival (Table II). We believe that the resected BRPC group of patients is a highly selected group with a unique tumor biology, demonstrating high performance status and a favorable response to therapy. In a sense, we conjecture that the overall good performance status of this group of patients allows them to tolerate complications better than a typical patient with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Finally, patients too sick to undergo surgery were excluded from this study by the exclusion criteria and excluded from standard treatment by not starting neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

There are three significant limitations to this analysis. First, this is a retrospective review of a prospective database. Although we utilized a robust data warehouse associated with the electronic medical record, biases such as selection bias may exist. Second, the numbers of patients included were relatively low. Finally, there was variability in the time interval between neoadjuvant therapy and surgery. The NLR is very sensitive measure of systemic inflammation.

Conclusions

This is the first investigation demonstrating an independent, inverse association between survival and increased NLR after neoadjuvant therapy for patients with BRPC. Because NLR is a relatively straightforward determination obtained from routine blood tests, there are many opportunities for future research utilizing this as a robust predictive biomarker. In addition, a prospective trial modulating inflammation with anti-inflammatories (such as statins or NSAIDs) during neoadjuvant therapy may yield a useful and safe strategy to improve outcomes in patients with BRPC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rasa Hamilton and Kim Murphy for administrative support. This work has been supported in part by the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292). Parts of this work were presented at the 11th Annual Academic Surgical Congress in Jacksonville, FL, February 2-4, 2016

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cid-Arregui A, Juarez V. Perspectives in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9297–316. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i31.9297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao J, Hwang SH, Li H, Liu JY, Hammock BD, Yang GY. Inhibition of Chronic Pancreatitis and Murine Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia by a Dual Inhibitor of c-RAF and Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase in LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx-1-Cre Mice. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:27–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stark AP, Chang HH, Jung X, Moro A, Hertzer K, Xu M, et al. E-cadherin expression in obesity-associated, Kras-initiated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Surgery. 2015;158:1564–72. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lohinai Z, Dome P, Szilagyi Z, Ostoros G, Moldvay J, Hegedus B, et al. From bench to bedside: attempt to evaluate repositioning of drugs in the treatment of metastatic small cell lung cancer (SCLC) PloS One. 2016;11:e0144797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macfarlane TV, Murchie P, Watson MC. Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug prescriptions and survival after the diagnosis of head and neck and oesophageal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39:1015–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens L, Pathak S, Nunes QM, Pandanaboyana S, Macutkiewicz C, Smart N, et al. Prognostic significance of pre-operative C-reactive protein and the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in resectable pancreatic cancer: a systematic review. HPB. 2015;17:285–91. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geng Y, Qi Q, Sun M, Chen H, Wang P, Chen Z. Prognostic nutritional index predicts survival and correlates with systemic inflammatory response in advanced pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han S, Liu Y, Li Q, Li Z, Hou H, Wu A. Pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with neutrophil and T-cell infiltration and predicts clinical outcome in patients with glioblastoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:617. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1629-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang GM, Zhu Y, Gu WJ, Zhang HL, Shi GH, Ye DW. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts prognosis in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving targeted therapy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0894-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcea G, Ladwa N, Neal CP, Metcalfe MS, Dennison AR, Berry DP. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with reduced disease-free survival following curative resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2011;35:868–72. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-0984-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng H, Long F, Jaiswar M, Yang L, Wang C, Zhou Z. Prognostic role of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11026. doi: 10.1038/srep11026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mettu NB, Abbruzzese JL. Clinical Insights Into the Biology and Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:17–23. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmer R, Goumas FA, Waetzig GH, Rose-John S, Kalthoff H. Interleukin-6: a villain in the drama of pancreatic cancer development and progression. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2014;13:371–80. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(14)60259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glazer ES, Amini A, Jie T, Gruessner RW, Krouse RS, Ong ES. Recognition of complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer determines inpatient mortality. JOP. 2013;14:626–31. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mellon EA, Hoffe SE, Springett GM, Frakes JM, Strom TJ, Hodul PJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of induction chemotherapy and neoadjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy for borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:979–85. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1004367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel M, Hoffe S, Malafa M, Hodul P, Klapman J, Centeno B, et al. Neoadjuvant GTX chemotherapy and IMRT-based chemoradiation for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:155–61. doi: 10.1002/jso.21954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmad J, Grimes N, Farid S, Morris-Stiff G. Inflammatory response related scoring systems in assessing the prognosis of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2014;13:474–81. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(14)60284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruckert F, Brussig T, Kuhn M, Kersting S, Bunk A, Hunger M, et al. Malignancy in chronic pancreatitis: analysis of diagnostic procedures and proposal of a clinical algorithm. Pancreatology. 2013;13:243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobrila-Dintinjana R, Vanis N, Dintinjana M, Radic M. Etiology and oncogenesis of pancreatic carcinoma. Collegium Antropol. 2012;36:1063–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dite P, Hermanova M, Trna J, Novotny I, Ruzicka M, Liberda M, et al. The role of chronic inflammation: chronic pancreatitis as a risk factor of pancreatic cancer. Dig Dis. 2012;30:277–83. doi: 10.1159/000336991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szkandera J, Stotz M, Eisner F, Absenger G, Stojakovic T, Samonigg H, et al. External validation of the derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker on a large cohort of pancreatic cancer patients. PloS One. 2013;8:e78225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giakoustidis A, Neofytou K, Khan AZ, Mudan S. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts pattern of recurrence in patients undergoing liver resection for colorectal liver metastasis and thus the overall survival. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:445–50. doi: 10.1002/jso.23845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin H, Zhang G, Liu X, Liu X, Chen C, Yu H, et al. Blood neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival for stages III-IV gastric cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:112. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guthrie GJ, Roxburgh CS, Farhan-Alanie OM, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Comparison of the prognostic value of longitudinal measurements of systemic inflammation in patients undergoing curative resection of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:24–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorente D, Mateo J, Templeton AJ, Zafeiriou Z, Bianchini D, Ferraldeschi R, et al. Baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with survival and response to treatment with second-line chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer independent of baseline steroid use. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:750–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto T, Yagi S, Kinoshita H, Sakamoto Y, Okada K, Uryuhara K, et al. Long-term survival after resection of pancreatic cancer: a single-center retrospective analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:262–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu W, He J, Cameron JL, Makary M, Soares K, Ahuja N, et al. The impact of postoperative complications on the administration of adjuvant therapy following pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2873–81. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3722-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]