Abstract

Background

Despite a lack of evidence showing improved clinical outcomes with robotic-assisted hysterectomy over other minimally-invasive routes for benign indications, this route has increased in popularity over the last decade.

Objective

Compare clinical outcomes and estimated cost of robotic-assisted versus other routes of minimally-invasive hysterectomy for benign indications.

Study Design

A statewide database was used to analyze utilization and outcomes of minimally-invasive hysterectomy performed for benign indications from January 1, 2013 – July 1, 2014. A one-to-one propensity score-match analysis was performed between women who had a hysterectomy with robotic assistance versus other minimally-invasive routes (laparoscopic and vaginal, with or without laparoscopy). Perioperative outcomes, intraoperative bowel and bladder injury, 30-day postoperative complications, readmissions, and reoperations were compared. Cost estimates of hysterectomy routes, surgical site infection, and postoperative blood transfusion were derived from published data.

Results

8,313 hysterectomy cases were identified: 4,527 performed using robotic-assistance and 3,786 performed using other minimally-invasive routes. 1,338 women from each group were successfully matched using propensity score-matching. Robotic-assisted hysterectomies had lower estimated blood loss (94.2 ±124.3 vs. 175.3 ±198.9 mL, p <.001), longer surgical time (2.3 ± 1.0 vs 2.0 ± 1.0 hours, p<.001), larger specimen weights (178.9 ± 186.3 vs 160.5 ± 190 g, p =.007) and shorter length of stay (14.1% (189) vs 21.9% (293) ≥ 2 days, p<.001). Overall, the rate of any postoperative complication was lower with the robotic-assisted route (3.5% (47) vs 5.6% (75), p=.01) and driven by lower rates of superficial SSI (0.07% (1) vs 0.7% (9), p =.01) and blood transfusion (0.8% (11) vs 1.9% (25), p=.02). Major postoperative complications, intraoperative bowel and bladder injury, readmissions, and reoperations were similar between groups. Using hospital cost estimates of hysterectomy routes and considering the incremental costs associated with surgical site infections and blood transfusions, non-robotic minimally-invasive routes had an average net savings of $3,269 per case, or 24% lower cost, compared to robotic-assisted hysterectomy ($10, 160 vs $13,429).

Conclusions

Robotic-assisted laparoscopy does not decrease major morbidity following hysterectomy for benign indications when compared to other minimally-invasive routes. While superficial surgical site infection and blood transfusion rates were statistically lower in the robotic-assisted group, in the absence of substantial reductions in clinically and financially burdensome complications, it will be challenging to find a scenario in which robotic-assisted hysterectomy is clinically superior and cost-effective.

Keywords: Complications, Cost, Hysterectomy, Minimally-invasive, Robotic

Condensation

For benign hysterectomy, the robotic-assisted route does not decrease major morbidity and is more expensive than other minimally-invasive routes.

Introduction

Over the last decade, the popularization of robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy has provided an alternative approach to performing minimally-invasive hysterectomy. While the decrease in abdominal hysterectomy rates seen over this same time period is indeed a positive trend,1,2 the superiority of the robotic-assisted route over other minimally-invasive surgical (MIS) routes for benign hysterectomy has yet to be proven.3–7 Although cited benefits of the robotic-assisted route over conventional laparoscopy include lower estimated blood loss and shorter length of stay, complication rates appear to be similar and costs significantly higher with robotic technology. 4,8–12 Vaginal hysterectomy remains the preferred route when possible and is recommended as such by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.13 However, few comparative studies of robotic hysterectomy actually include vaginal approaches. A retrospective study by Orady et al reported shorter operative time and greater blood loss with vaginal versus robotic hysterectomy.14 While major complication rates were comparable, this study was likely underpowered to detect some differences due to its small sample size.

Because complication rates following hysterectomy are relatively low, analyzing large clinical or administrative datasets is the only realistic way to evaluate differences in outcomes between MIS approaches. Therefore, using data from a statewide quality improvement collaborative, our aim was to compare perioperative outcomes and complications of hysterectomies performed for benign indications with robotic-assistance versus all other MIS routes, including conventional laparoscopy, vaginal, and laparoscopic-assisted vaginal routes. As a secondary aim, we sought to compare estimated costs of robotic-assisted laparoscopy to all other MIS routes using published cost data.

Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective study using data from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC), a Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network-funded database voluntarily populated by both academic and community hospitals throughout the state. Data are abstracted from charts by specially trained, dedicated nurse abstractors. Patient characteristics, intraoperative processes of care, and 30-day postoperative outcomes from hysterectomy cases at member hospitals are routinely collected. To reduce sampling error, a standardized data collection methodology is employed that uses only the first 25 cases of an 8-day cycle (alternating on different days of the week for each cycle). Routine validation of the data is maintained by scheduled site visits, conference calls, and internal audits.15 The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board granted “Not Regulated” status to this study (HUM00073978).

Hysterectomies available from the MSQC database and performed for benign indications using a minimally-invasive (MIS) route between January 1, 2013 and July 1, 2014 were analyzed as part of the study. Minimally-invasive hysterectomy cases were dichotomized into those performed using robotic-assisted laparoscopy and all others (vaginal, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal, and conventional laparoscopy). Bivariate analyses were used to compare the following clinical and demographic characteristics between robotic-assisted and other MIS routes: age (years), body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), race, smoker, hypertension, American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) Class,16 age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), prior pelvic surgery, insurance type, teaching hospital, and hospital bedsize. The CCI is a validated scoring system used to stratify patients based on specific comorbidities and age at admission for surgery.17 A higher CCI score indicates increased severity of condition and is correlated with increased ten-year mortality. Insurance type was categorized as follows: private, Medicare, Medicaid, both Medicare and Medicaid, uninsured, missing, and other. The “other” category included self-pay, government-sponsored plans excluding Medicare or Medicaid (ex: Veteran’s Affairs, TriCare), Worker’s Compensation, and auto insurance.

Propensity score-matching was performed in order to minimize selection bias and control for clinically relevant variables. Using the demographic, clinical, and hospital factors described above in a multivariable logistic regression model, a propensity score ranging from 0–1 was generated for each case. A one-to-one propensity score-match analysis using a caliper of 0.001 was performed between women who had a hysterectomy using robotic assistance versus other MIS routes. The matches between groups were assessed with a standardized difference score ≤ 0.1 for every covariate considered to indicate a good match.18 Perioperative variables including estimated blood loss (mL), surgical time (hours), specimen weight (grams), and length of stay (days), as well as surgical complications, were compared between the propensity score-matched cohorts. Intraoperative complications included those involving the bowel and bladder. Postoperative complications within 30 days of the hysterectomy included: superficial surgical site infection (SSI), deep/organ space SSI, deep venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction/stroke, pneumonia, sepsis, urinary tract infection, and blood transfusion. “Any complication” included occurrence of any of the previously listed intraoperative or postoperative complications. “Major postoperative complications” included the following: deep/organ space SSI, deep venous or pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction/stroke, pneumonia, sepsis, and death. “Any SSI” included both superficial and deep/organ space SSI. Hospital readmission and reoperation were also compared between the two groups. The paired t-test was used for continuous variables and Chi-Square for categorical variables.

For variables significant in pairwise comparisons between the robotic and other MIS groups, we subdivided the other MIS group into vaginal, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal, and laparoscopic routes. Overall comparisons with the robotic group were calculated and then pairwise comparisons between each specific route and the robotic group were performed. Overall p values for continuous variables were calculated using ANOVA. P values for continuous variables with robotic hysterectomies as referent surgical approach were calculated using Generalized Linear Models (GLM) with Dunnett-Hsu post-hoc p value adjustment for multiple pairwise comparisons. Significance was assessed for categorical variables using Chi-Square test or, in the case of small cell sizes, Fisher’s Exact Test. For categorical variables, multiple pairwise comparisons were initially calculated using Chi-Square tests or, in the case of small cell sizes, Fisher’s Exact test with a post-hoc Sidak p value adjustment.

Cost estimates were derived from published data on hospital costs by hysterectomy route, surgical site infection (SSI), and postoperative blood transfusion. The equation used to estimate cost differences between robotic-assisted and other MIS routes is presented in the Appendix. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (Copyright 2014, SAS Institute, Inc.).

Results

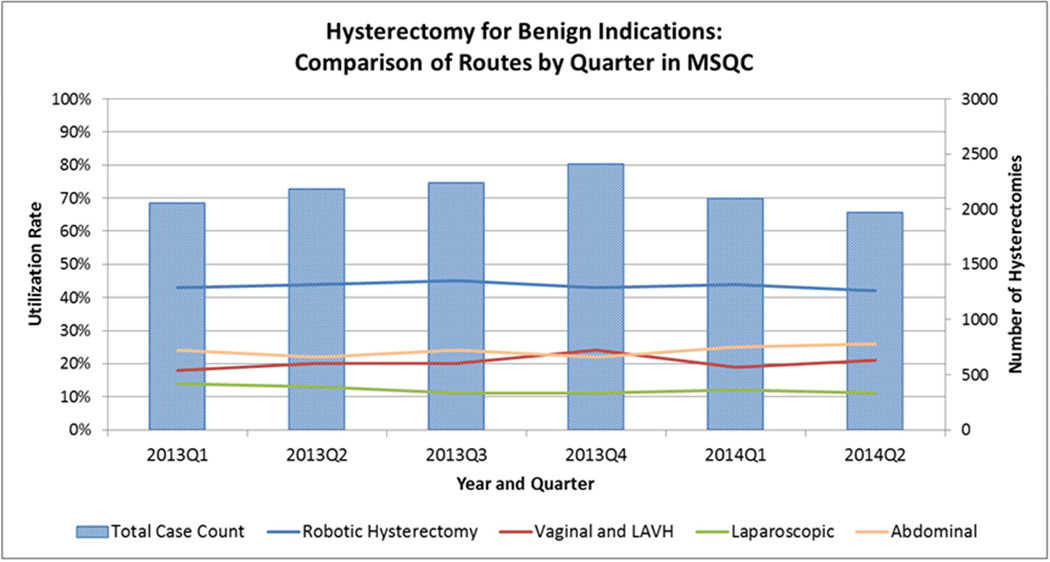

We identified 8,313 cases of benign hysterectomy during the study period: 4,527 performed using robotic assistance and 3,786 performed using other MIS routes. The proportion of hysterectomies performed by route ranged from 43–45% for robotic-assisted, 10–13% for laparoscopy, and 19–24% for vaginal, with or without laparoscopy (Figure 1). Prior to propensity score-matching, groups differed significantly by nearly all demographic, clinical, and hospital factors (Table 1). Compared to other MIS routes, women undergoing robotic-assisted hysterectomy were younger and more frequently non-white. They also had a higher mean BMI and more frequently reported smoking. Comorbidities including hypertension and ASA Class 3 were less frequent in women undergoing robotic-assisted hysterectomy, and these women also more frequently had a history of prior pelvic surgery. Furthermore, a greater proportion of women having robotic-assisted hysterectomy had private insurance and significantly fewer had Medicare, no insurance, or “other insurance.” Finally, hospital characteristics differed between groups. Compared to other MIS routes, a greater proportion of robotic-assisted hysterectomies were performed at teaching hospitals and at those with < 500 beds.

Figure 1.

Hysterectomy for Benign Indications: Comparison of Routes by Quarter in MSQC

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of women who underwent minimally-invasive hysterectomy for benign indications, comparing robotic-assisted versus other MIS routes

| Unadjusted |

Propensity Score-Matched |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Characteristic |

Robotic (n=4527) |

Other MIS Routes (n=3786) |

P Value |

Robotic (n=1338) |

Other MIS Routes (n=1338) |

P Value |

| Age (years) | 46.4 ±10.1 | 48.9 ±12.0 | <.001 | 46.7 ±9.7 | 46.5±10.0 | .52 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 30.9 ±7.9 | 29.6 ±7.0 | <.001 | 29.8 ±7.1 | 29.8 ±6.5 | .95 |

| Caucasian | 82.8 (3559/4296) |

85.0 (3039/3557) |

.01 | 83.5 (1117) | 83.5 (1117) | 1.00 |

| Smoker | 24.3 (1102) | 22.2 (840) | .02 | 23.8 (319) | 24.5 (328) | .68 |

| Hypertension | 25.5 (1156) | 28.2 (1066) | .01 | 25.3 (339) | 24.7 (330) | .69 |

| Arrhythmia | 2.0 (89) | 2.0 (77) | .83 | 1.9 (25) | 1.6 (22) | .66 |

| ASA Class 1 | 10.9 (493) | 11.2 (425) | .38 | 11.4 (152) | 11.3 (151) | .95 |

| ASA Class 2 | 72.3 (3272) | 69.3 (2625) | .01 | 71.7 (959) | 72.4 (969) | .67 |

| ASA Class 3 | 16.8 (762) | 19.4 (736) | .01 | 17.0 (227) | 16.3 (218) | .64 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index |

5.2±1.2 | 5.5±1.5 | <.001 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | .36 |

| Prior Pelvic Surgery | 61.1 (2765) | 58.7 (2223) | .03 | 61.4 (822) | 60.5 (809) | .61 |

| Insurance Type | ||||||

| Private | 75.9 (3438) | 69.3 (2624) | <.0001 | 75.4 (1009) | 76.6 (1025) | .47 |

| Medicare | 8.7 (395) | 12.8 (484) | <.0001 | 8.0 (107) | 8.1 (108) | .94 |

| Medicaid | 9.5 (431) | 8.7 (328) | .18 | 11.1 (149) | 10.2 (136) | .42 |

| Medicare & Medicaid | 1.7 (78) | 1.9 (71) | .60 | 2.3 (31) | 1.6 (22) | .22 |

| Other | 3.5 (160) | 6.1 (232) | <.0001 | 3.0 (40) | 3.1 (42) | .82 |

| Uninsured | 0.5 (24) | 1.2 (45) | .001 | 0.2 (2) | 0.3 (4) | .41 |

| Missing | 0.02 (1) | 0.05 (2) | .46 | 0 | 0.07 (1) | .32 |

| Teaching Hospital | 62.8 (2844) | 59.9 (2268) | .01 | 60.1 (811) | 60.0 (803) | .75 |

| Hospital Size ≥500 Beds | 14.9 (676) | 22.5 (850) | <.0001 | 13.5 (180) | 14.5 (194) | .44 |

Data presented as mean ± SD, % (n), or median (IQR). P values determined using Chi-square or paired t-test.

After performing propensity score-matching, 1,338 women from each group were successfully matched so that the previously mentioned differences noted using unadjusted comparisons were no longer present (Table 1). Table 2 shows the results of the comparisons between the propensity score-matched cohorts of women having robotic versus other MIS routes of hysterectomy regarding perioperative outcomes, complications, readmissions, and reoperations. Robotic-assisted hysterectomies had lower estimated blood loss (by an average of 81 mL), longer mean surgical time (by 18 minutes), and larger specimen weights (by 18 grams). A lower proportion of women undergoing robotic-assisted hysterectomy stayed two or more days in the hospital compared to those undergoing other MIS routes.

Table 2.

Perioperative outcomes and complications within 30 days of hysterectomy, comparing robotic-assisted versus other MIS routes

| Perioperative Outcome | Robotic ( n=1338) |

Other MIS Routes (n=1338) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Blood Loss, mL | 94.2 ±124.3 | 175.3 ±198.9 | <.001 |

| Surgical Time, hours | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | <.001 |

| Specimen Weight, grams | 178.9 ± 186.3 | 160.5 ± 190 | <.007 |

| Length of Stay ≥ 2 days | 14.1 (189) | 21.9 (293) | <.001 |

| Complications | |||

| Any Complication | 3.5 (47) | 5.6 (75) | .01 |

| Major Postoperative Complications | 1.4 (19) | 1.6 (22) | .64 |

| Postoperative Complications | |||

| Any Surgical Site Infection (SSI) | 0.8 (11) | 1.4 (18) | .19 |

| Superficial SSI | 0.07 (1) | 0.7 (9) | .01 |

| Deep/Organ Space SSI | 0.6 (8) | 0.8 (10) | .64 |

| Deep Venous Thromboembolism | 0.07 (1) | 0.07 (1) | 1.00 |

| Pulmonary Embolism | 0.07 (1) | 0.3 (4) | .18 |

| Myocardial Infarction/Stroke | 0 | 0 | -- |

| Pneumonia | 0.07 (1) | 0.07 (1) | 1.00 |

| Sepsis | 0.7 (9) | 0.8 (10) | .82 |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 1.4 (19) | 1.6 (21) | .75 |

| Blood Transfusion | 0.8 (11) | 1.9 (25) | .02 |

| Intraoperative Complications | |||

| Bowel | 0.6 (8) | 0.2 (2) | .06 |

| Bladder | 0.8 (10) | 0.8 (10) | 1.00 |

| Readmission | 3.0 (39/1293) | 2.9 (37/1292) | .81 |

| Reoperation | 2.0 (26/1290) | 2.2 (28/1291) | .79 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | -- |

Data presented as mean ± SD, % (n), or median (IQR). P values determined using Chi-square or paired t-test.

Overall, the rate of any complication was lower with robotic-assisted versus other MIS hysterectomy routes (3.5% vs 5.6%, p=.01). However, major postoperative complications and intraoperative bowel and bladder injury were no different between groups. Readmission and reoperation rates were also similar, and there were no deaths within 30 days of surgery in either group. The two complications that occurred less frequently in the robotic-assisted hysterectomy cohort included superficial SSI and blood transfusion. While superficial SSI was statistically lower in the robotic-assisted hysterectomy group, the prevalence was low and less than 1% in both groups. Postoperative blood transfusions occurred half as frequently following robotic-assisted hysterectomy; although again, prevalence was low and < 2% in the non-robotic group.

To determine whether a specific minimally-invasive route in the “other MIS” group was driving any of these differences, outcomes that were significant in Table 2 were compared between the robotic group and vaginal, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal, and laparoscopic hysterectomy routes (Table 3). Significance for the overall comparisons was unchanged with the exception of postoperative blood transfusion, which became non-significant. In pairwise comparisons, the blood transfusion rate remained significantly lower in the robotic group only in comparison to the laparoscopic route, but not compared to vaginal and laparoscopic-assisted vaginal routes. The laparoscopic group was also found to have significantly greater mean specimen weight. While the rate of superficial SSI remained significantly higher in the laparoscopic versus robotic group, similar rates of any complication were found. Differences in the occurrence of any complication and superficial SSI were also non-significant when comparing the vaginal versus robotic group. Vaginal hysterectomy remained the only route with significantly shorter operating time.

Table 3.

Comparison of perioperative outcomes and complications by specific MIS route

| Other MIS Routes |

Overall P Value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perioperative Outcome | Robotic ( n=1338) |

TVHa (n=361) |

LAVHb (n=438) |

Laparoscopic (n=539) |

|

| Estimated Blood Loss, mL | 94.2 ±124.3 | 157.2 ± 140.4 | 190.1 ±173.1 | 175.4 ± 245.7 | |

| P value vs Robotic | -- | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Surgical Time, hours | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | |

| P value vs Robotic | -- | <.001 | .17 | .16 | <.001 |

| Specimen Weight, grams | 178.9 ± 186.3 | 111 ± 74.4 | 147.2 ± 97.1 | 205.2 ± 274.5 | |

| P value vs Robotic | -- | <.001 | .01 | .02 | <.001 |

| Length of Stay ≥ 2 days | 14.1 (189) | 23.3 (84) | 14.8 (65) | 26.7 (144) | |

| P value vs Robotic | -- | <.001 | .98 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Complications | |||||

| Any Complication | 3.51 (47) | 5.54 (20) | 6.62 (29) | 4.82 (26) | .04 |

| P value vs Robotic | -- | .22 | .02 | .46 | |

| Superficial SSI | 0.07 (1) | 0 | 0.91 (4) | 0.93 (5) | .01 |

| P value vs Robotic | -- | 1.00 | .01 | .01 | |

| Blood Transfusion | 0.82 (11) | 1.66 (6) | 1.83 (8) | 2.04 (11) | .12 |

| P value vs Robotic | -- | .23 | .10 | .03 | |

Data presented as mean ± SD or % (n). Overall p values for continuous variables determined using ANOVA. Pairwise comparisons with robotic hysterectomy as the referent group calculated using Generalized Linear Models with Dunnett-Hsu post-hoc p value adjustment. Chi-Square or Fisher’s Exact tests used for categorical variables.

Total vaginal hysterectomy

Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy

Our cost estimate was based on data from several published studies. Dayartna et al performed an analysis of total hospital costs for minimally-invasive hysterectomy routes from 2007–2010 at a single academic institution and found robotic-assisted hysterectomy to be the most expensive route at $13,429, followed by conventional laparoscopy ($11,558), vaginal with laparoscopy ($10,069), and vaginal ($7,903).11 Purchase cost of the robot (approximately $2.5 million) was not included in this estimate.10 Mean weighted average cost of the non-robotic MIS hysterectomy routes was $10,084 per case. Roy et al performed an analysis on the prevalence and impact of SSI after hysterectomy and found that SSI doubles the cost of hysterectomy.19 Finally, Shander et al performed an analysis of the cost of blood transfusion in post-surgical patients that incorporated both direct and indirect costs and determined the mean per-red blood cell (RBC)-unit cost to be $761.20 Using these cost estimates and considering the incremental costs associated with SSI and blood transfusion complications (assuming transfusion of 2 units of RBCs), non-robotic MIS routes had an average net savings of $3,269 per case, or 24% lower cost, compared to robotic-assisted hysterectomy ($10,160 vs $13,429; see Appendix for equation). This calculation does not take into consideration purchase or maintenance cost of the robot.

Comment

In this propensity score-matched cohort of women who underwent minimally-invasive hysterectomy for benign indications, robotic-assisted hysterectomy was associated with similar major postoperative complications, intraoperative injuries, readmissions, and reoperations. Robotic-assisted hysterectomy was associated with significantly lower rates of superficial SSI and blood transfusion compared to all other MIS routes.

Results from this analysis support existing data that have consistently failed to provide evidence that widespread adoption of robotic-assisted hysterectomy for benign indications would significantly decrease major morbidity compared to other MIS approaches. Using a national database, a propensity match analysis by Wright et al found similar rates of intraoperative and postoperative complications in robotic-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy.5 Albright et al recently performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing the same groups and also found similar rates of mild, moderate, and severe complications.7 Although our analysis does show a statistically significant reduction in blood transfusion and superficial SSI rates with the robotic-assisted route compared to other MIS routes, these complications were rare and the difference may not be clinically significant. Furthermore, when a sub-analysis was performed between the specific MIS routes, increased rates of blood transfusion in the laparoscopic group appeared to be driving the overall difference compared to robotic hysterectomies. The laparoscopic group was also found to have significantly greater mean specimen weight, which may help explain the difference in blood transfusions.

Our study extends the existing literature in several ways. First, our study expands the comparison of robotic-assisted hysterectomy to all MIS routes, not just conventional laparoscopy. This is important because as demonstrated by the national trend, the increase in robotic-assisted hysterectomy is not only associated with decreased rates of abdominal hysterectomy, but also decreased utilization of other MIS routes.2,5 We believe that the inclusion of all alternative minimally-invasive methods to robotic laparoscopy is critical in this analysis, as some cases are more appropriate for a vaginal approach, with or without laparoscopy. Furthermore, vaginal hysterectomy is the preferred approach when possible, and should therefore not be excluded when comparing MIS routes.13 Second, prior studies have reported a relatively low rate of robotic-assisted hysterectomy with a significant increase in utilization of this route over the study period. These are periods of time when the operative outcomes are more likely to reflect a learning curve.21 In contrast, in the current study, the use of robotic-assisted laparoscopy was consistently several-fold higher than the national average over the study time period—a pattern of practice that should reduce the effect of the learning curve on surgical outcomes. The high utilization of robotic-assisted hysterectomy in our population may help explain the lower rate of blood transfusion not previously observed. However, this benefit should be interpreted in the context of increased costs associated with robotic-assisted hysterectomy.

While considering the incremental costs associated with SSI and blood transfusion complications, non-robotic MIS routes still had 24% lower cost compared to the robotic-assisted route. It is relevant to mention that we likely overestimated the cost of superficial SSI cases based on results from Roy et al that showed a two-fold increased cost for the occurrence of any SSI. The cost of antimicrobials would not likely double the hysterectomy cost; however, in the absence of more accurate published cost-estimates specific to superficial SSI, we decided to err on the side of overestimating versus underestimating cost. Our results regarding cost are consistent with published data showing significantly increased costs with robotic-assisted hysterectomy.4,8–12 As surgeons, we have an obligation to consider the cost-benefit ratio of our interventions and balance our goals of optimizing clinical outcomes and practicing good stewardship of our healthcare resources.

Limitations to our study include the retrospective design and potential for loss of follow-up if patients were seen for postoperative complications at non-MSQC member hospitals. We also could not accurately assess surgeon volume or experience, as the MSQC data collection methodology is based on a sampling of cases from participating hospitals. Finally, our cost estimates were based on published data and not specific to hysterectomies in the MSQC database. The estimates of cost by hysterectomy route came from a study done at a single academic institution, which may limit the generalizability of these results.

Strengths include a large database with validated data collection by specially trained, dedicated nurse data abstractors. Furthermore, the utilization of the robotic-assisted approach remained stable throughout the study period, which would limit the impact of the learning curve on our results.

In conclusion, robotic-assisted laparoscopy does not decrease major morbidity following hysterectomy for benign indications when compared to other MIS routes. In the absence of substantial reductions in clinically and financially burdensome complications, it will be challenging to find a scenario in which robotic-assisted hysterectomy is clinically superior and cost-effective.

Acknowledgments

Study conducted in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative is funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network.

Investigator support for C.W.S. was provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development WRHR Career Development Award # K12 HD065257. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix

Hospital cost of robotic hysterectomy = $13,42911

Weighted average hospital cost of non-robotic MIS hysterectomy route = $10, 084

-

Calculated as follows for the propensity matched cohort of 1,338 cases:

Mean cost of blood transfusion per unit = $76120

Cost of any SSI = 2 × cost of hysterectomy19

Cost of Other MIS Hysterectomy Routes Including Additional Blood Transfusion and Superficial SSI Cases

| Cost of robotic hysterectomies | 1,338 × $13,429 | = $17,968,002 | |

| Cost of other MIS hysterectomy routes |

1,338 × $10,084 | = $13,492,392 + | |

| Additional cases of superficial SSI |

8 × $10,084 | = $80,672 + | |

| Additional blood transfusions | 14 × $761/unit × 2 units | = $21,308 | |

| = $13,594,372 | |||

| Difference in cost between robotic hysterectomy and other MIS hysterectomy routes with increased complications observed in this analysis |

= $17,968,002 − $13,594,372 = $4,373,630 |

||

| Per case savings | =$4,373,630 ÷ 1,338 cases =$3,269 per case |

||

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wu JM, Wechter ME, Geller EJ, Nguyen TV, Visco AG. Hysterectomy rates in the United States, 2003. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1091–1095. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000285997.38553.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai VB, Xu X. An update on inpatient hysterectomy routes in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:742–743. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu H, Lawrie TA, Lu D, Song H, Wang L, Shi G. Robot-assisted surgery in gynaecology. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014;12:CD011422. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosero EB, Kho KA, Joshi GP, Giesecke M, Schaffer JI. Comparison of robotic and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:778–786. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a4ee4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright JD, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, et al. Robotically assisted vs laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with benign gynecologic disease. Jama. 2013;309:689–698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarlos D, Kots L, Stevanovic N, von Felten S, Schar G. Robotic compared with conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:604–611. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318265b61a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albright BB, Witte T, Tofte AN, et al. Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Hysterectomy for Benign Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright JD, Ananth CV, Tergas AI, et al. An economic analysis of robotically assisted hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1038–1048. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tandogdu Z, Vale L, Fraser C, Ramsay C. A Systematic Review of Economic Evaluations of the Use of Robotic Assisted Laparoscopy in Surgery Compared with Open or Laparoscopic Surgery. Applied health economics and health policy. 2015;13:457–467. doi: 10.1007/s40258-015-0185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbash GI, Glied SA. New technology and health care costs--the case of robot-assisted surgery. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:701–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dayaratna S, Goldberg J, Harrington C, Leiby BE, McNeil JM. Hospital costs of total vaginal hysterectomy compared with other minimally invasive hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:120, e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapper AM, Hannola M, Zeitlin R, Isojarvi J, Sintonen H, Ikonen TS. A systematic review and cost analysis of robot-assisted hysterectomy in malignant and benign conditions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;177:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 444: choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1156–1158. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c33c72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orady M, Hrynewych A, Nawfal AK, Wegienka G. Comparison of robotic-assisted hysterectomy to other minimally invasive approaches. JSLS : Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons /Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2012;16:542–548. doi: 10.4293/108680812X13462882736899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell DA, Jr, Kubus JJ, Henke PK, Hutton M, Englesbe MJ. The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative: a legacy of Shukri Khuri. Am J Surg. 2009;198:S49–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owens WD, Felts JA, Spitznagel EL., Jr ASA physical status classifications: a study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:239–243. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Austin PC. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate behavioral research. 2011;46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roy S, Patkar A, Daskiran M, Levine R, Hinoul P, Nigam S. Clinical and economic burden of surgical site infection in hysterectomy. Surgical infections. 2014;15:266–273. doi: 10.1089/sur.2012.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shander A, Hofmann A, Ozawa S, Theusinger OM, Gombotz H, Spahn DR. Activity-based costs of blood transfusions in surgical patients at four hospitals. Transfusion. 2010;50:753–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woelk JL, Casiano ER, Weaver AL, Gostout BS, Trabuco EC, Gebhart JB. The learning curve of robotic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:87–95. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31827a029e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]