STRUCTURED ABSTRACT

Background

Recent data establishes a strong link between peer video ratings of surgical skill and clinical outcomes with laparoscopic gastric bypass. Whether skill for one bariatric procedure can predict outcomes for another, related procedure is unknown.

Methods

Twenty surgeons voluntarily submitted videos of a standard laparoscopic gastric bypass procedure, which was blindly rated by 10 or more peers using a modified version of the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS). Surgeons were divided into quartiles for skill in performing gastric bypass and their outcomes within 30 days after sleeve gastrectomy were compared. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was utilized to adjust for patient risk factors.

Results

Surgeons with skill ratings in the top (n=5), middle (n=10, middle two combined), and bottom (n=5) quartiles for laparoscopic gastric bypass had similar rates of surgical and medical complications following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (top 5.7%, middle 6.4%, bottom 5.5%, p=0.13). Furthermore, surgeon skill ratings did not correlate with rates of reoperation, readmission and emergency department visits. Top rated surgeons had significantly faster operating room times for sleeve gastrectomy (top 76 min, middle 90 min, bottom 88 min; p<0.001) and a higher annual volume of bariatric cases per year (top 240, middle 147, bottom 105; p=0.001).

Conclusions

Video ratings of surgical skill with laparoscopic gastric bypass do not predict outcomes with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Evaluation of surgical skill with one procedure may not apply to other related procedures and may require independent assessment of surgical technical proficiency.

Keywords: bariatric surgery, outcomes, surgical quality complications, surgical skill

INTRODUCTION

It is well established that surgical outcomes vary widely across hospitals and surgeons. Numerous studies over the past two decades have demonstrated a relationship between outcomes and certain proxies for surgeon proficiency, including high surgeon- and hospital-volume, as well as subspecialty fellowship training.7, 9, 14, 16, 18 Recently, evidence has emerged demonstrating that peer-ratings of surgical skill from operative videos are highly correlated with better outcomes for laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery.3 This body of work has generated significant enthusiasm for using videos to study and improve the intra-operative details of surgical care via coaching or other methods.4, 8, 12, 17

Given the growing interest for studying surgeon skill as a measure of quality, it is important to understand whether these ratings can be extrapolated beyond the measured operation to other procedures within that surgeon’s practice. On one hand, many laparoscopic skills such as exposure, dissection, and tissue handling are relevant to a wide variety of procedures. On the other hand, surgical procedures may have certain technical steps that require procedure-specific skills. Each operation may require skills that may not be immediately translatable to other procedures. For example, when performing laparoscopic gastric bypass, one would have to be adept at performing gastrointestinal anastomoses (involving advanced laparoscopic stapling and suturing), a skill set which may not be essential for another common bariatric procedure, such as laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

In this context, we sought to assess the extent to which surgical skill ratings with one laparoscopic procedure (gastric bypass) correlate with outcomes for another, bariatric procedure (sleeve gastrectomy) performed by the same surgeons. Using data from the Michigan Bariatric Surgical Collaborative (MBSC), we compared video peer-ratings of surgical skill using a modified Objective Structures Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) assessment of surgeons performing a laparoscopic gastric bypass with risk-adjusted outcomes for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy among the same cohort of surgeons.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

This study was conducted based on the analysis of data from the Michigan Bariatric Surgical Collaborative (MBSC). The MBSC is a payer-funded consortium of 40 hospitals and 75 surgeons that submit data on all patients undergoing primary and revisional bariatric surgery. Since 2006, data on over 54,000 patients have been obtained and include a wide range of variables including information on demographic variables, preoperative comorbidities, perioperative process of care, 30-day complication rates and weight loss outcomes. Data obtained on patient variables are collected by centrally trained abstractors based on standardized definitions and are audited annually by external reviewers from the coordinating center to ensure accuracy and completeness of data.

This study included data on patients who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy between August 2006 and March 2015 by 20 surgeons who participated in this study (n=7,663). The study cohort was compared to the remaining patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy in the MBSC (n=9,577) in order to assess for patient bias. We found that both groups were similar with respect to mean BMI, age and rate of male patients, 30-day complications, reoperations, readmissions and emergency room visits. (Appendix 1)

Appendix 1.

Comparison between patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in study cohort and the remaining MBSC.

| Variable | Paents from 20 surgeons with skill rangs (n = 7663) | Remaining paents in MBSC (n=9577) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mean | 95% LCL | 95% UCL | Mean | 95% LCL | 95% UCL | P value | |

| BMI | 48.33 | 48.14 | 48.53 | 47.99 | 47.81 | 48.16 | 0.01 |

| Age | 46.10 | 45.84 | 46.36 | 45.56 | 45.32 | 45.79 | 0.00 |

| % Male | 24.23 | 23.27 | 25.19 | 23.10 | 22.25 | 23.94 | 0.08 |

| % Surgical Complicaons | 3.39 | 2.99 | 3.80 | 3.20 | 2.84 | 3.55 | 0.47 |

| % Medical Complicaons | 1.00 | 0.78 | 1.23 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 0.67 |

| % Reoperaons | 1.07 | 0.84 | 1.30 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 1.16 | 0.48 |

| % Readmissions | 4.14 | 3.69 | 4.58 | 3.99 | 3.60 | 4.38 | 0.63 |

| % ED visit | 7.48 | 6.89 | 8.07 | 7.91 | 7.37 | 8.46 | 0.28 |

Participating Surgeons and Raters

The objective of this study was to assess the outcomes of surgeons performing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy based on their peer-reviewed skill ratings of laparoscopic gastric bypass. Details of the video submission and rater review process are described in our previous study by Birkmeyer et al.3 To summarize, 20 surgeons participated in the study and submitted videos of a standard laparoscopic gastric bypass, which was edited to consist of three key technical components of the operation: 1) creation of the gastric pouch, 2) the gastrojejunostomy and 3) the jejunojejunostomy. Videos were free of patient identifiers and were also edited to eliminate images that may reveal the identity of the patient (i.e. camera exchanges to clean the lens or to move from one port to another). Each video was rated by 10 or more peers who were blinded to the identity of the operating surgeon. Overall, 33 surgeons from 24 hospitals served as raters from July 2011 and June 2012. Surgeons rated each video using a modified version of the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) ], which has been validated previously.6, 11 The assessment tool includes an evaluation of a surgeon’s tissue handling, time and motion, instrument handling, flow of operation, tissue exposure and overall technical skill. Surgeons were rated using a 1-to-5 anchored Likert-type scale. A skill rating of 1 indicated the level of a general surgery chief resident; 3 that of an average bariatric surgeon; and 5 that of a “master” surgeon. There was no attempt to teach raters or provide rating norms. Since each video was rated by a different groups of raters, a z score was calculated and it was determined that no rater’s score was significantly different from the mean. A sensitivity analysis was also performed in the prior study, which involved rating a video of a second operation from each surgeon in the best and worst quartiles of skill. This demonstrated that the mean ratings for the first and second videos were highly correlated. Finally, 5 non-Michigan surgeons rated the gastric bypass videos of surgeons in the highest and lowest skill quartiles. Mean ratings from Michigan and non-Michigan surgeons were also highly correlated and there was no overlap among mean ratings of surgeons in the highest and lowest quartiles. 3

Outcomes

The primary goal of this study was to determine whether peer-ratings of surgical skill from a video of laparoscopic gastric bypass were associated with risk-adjusted outcomes for patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. To assess outcomes, we used the following adverse events assessed in the MBSC clinical registry: any postoperative complications, reoperation, readmission, and emergency department visits. Postoperative complications included surgical-site infection, abdominal abscess, leak, bowel obstruction, bleeding, pneumonia, respiratory failure, renal failure, venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest and death.

Statistical Analysis

Surgeons were categorized into three groups according to quartiles of skill ratings: the bottom group (first quartile), middle group (second and third quartiles), and top group (fourth quartile) using methods previously described in our prior study.3 We compared risk-adjusted rates of complications between the three groups of surgeon skill ratings. We performed risk-adjustment using a multivariate logistic regression model with clustering of patients treated by surgeons to estimate the expected number of complications for each group of surgeon skill ratings. Risk-adjusted complication rates were then calculated as the ratio of observed number to the expected number of complications (observed-to-expected ratio) for each group of surgeon skill rating multiplied by the overall crude rate of complications. This model is adjusted for all patient variables that are measured in the MBSC dataset including demographics, preoperative comorbidities, and mobility limitations. For other specific risk-adjusted rates of complications, reoperations, readmissions and emergency department visits, we used multivariable logistic regression with forward stepwise selection using P<0.05 as the inclusion criteria to select other covariates. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, inc) and STATA, version 12.0 (Statacorp).

RESULTS

Surgeons Skill Ratings

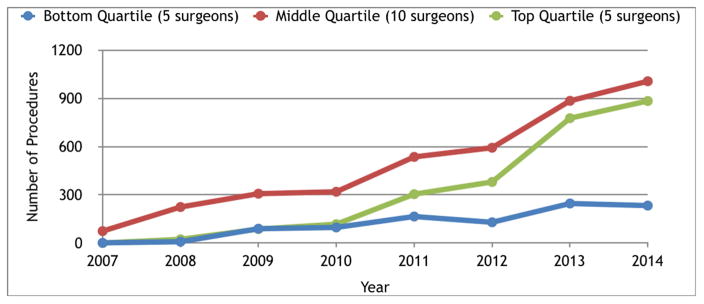

Summary ratings of surgical skill for gastric bypass varied substantially among surgeons in the study (range 2.9 – 4.4). (Table 1). Surgeons in the quartile with the highest skill rating also performed a significantly higher annual volume of bariatric procedures than those in the lowest quartile (240 vs 105 cases, p=0.01). The difference between the mean annual volume of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy was also higher (96 vs 33 cases) and trended towards statistical significance. Surgeons with higher skill ratings also had significantly faster mean operating times for both laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (76 min. vs. 88 min., p<0.001) and any bariatric procedure (84 min. vs. 113 min., p<0.001) when compared to the lowest skill quartile.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Surgeons, Patient Volume, and Surgery, According to peer rating of surgical skill

| Variable | Level of Surgical Skill | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Bottom | Middle | Top | ||

| Surgeons (N) | 5 | 10 | 5 | |

| Mean peer rating of technical skill* | ||||

| Gentleness | 3.3 | 3.9 | 4.4 | |

| Time and motion | 2.6 | 3.4 | 4.3 | |

| Instrument handling | 2.9 | 3.7 | 4.4 | |

| Flow of operation | 3.1 | 3.8 | 4.5 | |

| Tissue exposure | 3.0 | 3.9 | 4.4 | |

| Overall technical skill | 2.7 | 3.6 | 4.4 | |

| Summary rating | 2.9 | 3.7 | 4.4 | |

| Patients | ||||

| Undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy N(%) | 986 (23%) | 4045 (37%) | 2632 (27%) | |

| Undergoing any bariatric procedure | 4287 | 10814 | 9628 | |

| Mean annual procedure volume (N) | ||||

| Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 33 | 61 | 96 | 0.07 |

| Any bariatric procedure | 105 | 147 | 240 | 0.01 |

| Mean operating room times (min) | ||||

| Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 88 | 90 | 76 | <.001 |

| Any bariatric procedure | 113 | 107 | 84 | <.001 |

| Mean duration of bariatric surgery practice (yr) | 11 | 9 | 11 | 0.44 |

| Completion of fellowship in advanced laparoscopy of bariatric surgery (%) | 20 | 44 | 20 | 0.56 |

| Practicing at teaching hospital (%) | 60 | 70 | 40 | 0.63 |

Patient Characteristics

A total of 7,663 patients underwent sleeve gastrectomy by surgeons who participated in this study. Overall, the mean BMI was 48.3 kg/m2, mean age was 46.1 years and 24.2% of patients were male. There were small but statistically significant differences between certain patient demographics and comorbidities in each quartile, and these were fully accounted for in our risk-adjustment models. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, according to peer rating of surgical skill with laparoscopic gastric bypass.

| Patient Characteristic | Level of Surgical Skill | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Bottom | Middle | Top | ||

|

| ||||

| (5 surgeons, 986 patients) | (10 surgeons, 4045 patients) | (5 surgeons, 2632 patients) | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean age (yr) | 44.13 | 46.57 | 46.13 | <.001 |

| Male sex (%) | 23.12 | 25.27 | 23.06 | 0.08 |

| Private insurance (%) | 50.91 | 55.62 | 48.48 | <.001 |

| Clinical | ||||

| Mean body-mass index | 47.95 | 48.4 | 48.37 | 0.33 |

| Medical history (%) | ||||

| Musculoskeletal disorder | 72.41 | 64.75 | 78.31 | <.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 54.87 | 54.49 | 55.28 | 0.82 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 48.99 | 46.13 | 53.84 | <.001 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 46.35 | 40.74 | 48.14 | <.001 |

| Psychological conditions | 47.06 | 48.55 | 53.19 | <.001 |

| Sleep apnea | 49.49 | 43.91 | 48.02 | <.001 |

| Smoking | 34.18 | 41.84 | 41.32 | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 33.27 | 29.91 | 34.31 | <.001 |

| Cholelithiasis | 21.6 | 28.8 | 25.19 | <.001 |

| Lung disease | 26.37 | 21.88 | 28.88 | <.001 |

| Urinary incontinence | 21.1 | 14.17 | 17.02 | <.001 |

| Mobility problems | 3.35 | 5.22 | 4.48 | 0.04 |

| Liver disorder | 9.33 | 10.51 | 7.18 | <.001 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 3.45 | 4.25 | 3.91 | 0.48 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 3.35 | 2.47 | 2.7 | 0.31 |

Outcomes after Sleeve Gastrectomy

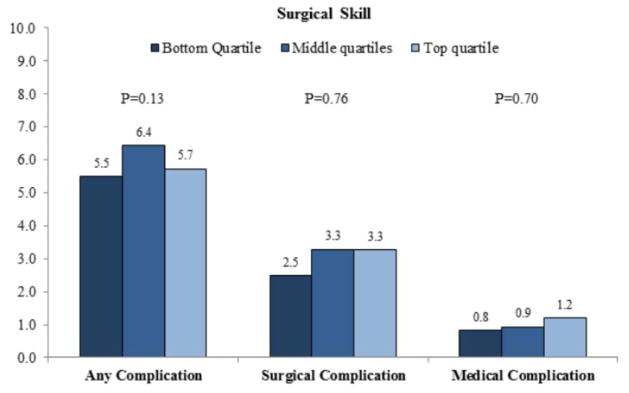

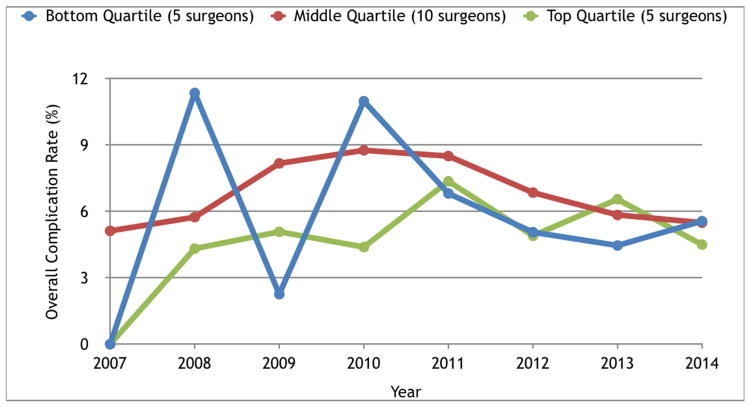

Risk-adjusted rates of complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for surgeons with different skill ratings are presented in Table 3. There were no significant differences in 30-day complications rates (surgical or medical) among patients in each quartile. (Figure 1) Surgeons with skill ratings in the top (n=5), middle (n=10, middle two combined), and bottom (n=5) quartiles for laparoscopic gastric bypass had similar overall complication rates following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (top 5.7%, middle 6.4%, bottom 5.5%, p=0.13). Mortality was low, with no deaths in the bottom quartile and 0.09% mortality rate in the top quartile (p=0.91). Likewise, the rate of leak or perforation among the three groups was low and not significantly different across groups (top rated surgeons, 0.85%, middle 0.39%, bottom 0.54%, p=0.85).

Table 3.

Risk-adjusted rates of complications with laparoscopic sleeve, according to peer rating of surgical skill with laparoscopic gastric bypass.

| Variable | Level of Surgical Skill | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Bottom | Middle percent | Top | ||

| Surgical complications | ||||

| Leak or perforation | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.85 |

| Obstruction | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.47 |

| Infection | 1.02 | 1.57 | 1.61 | 0.56 |

| Hemorrhage | 0.83 | 1.32 | 1.22 | 0.59 |

| Medical complications | ||||

| Venous thromboembolism | 0.09 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.68 |

| Cardiac complication | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.63 |

| Renal failure | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Pulmonary complication | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.73 | 0.36 |

| Death | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.91 |

Figure 1.

Risk-adjusted complication rates with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, according to quartile of surgical skill.

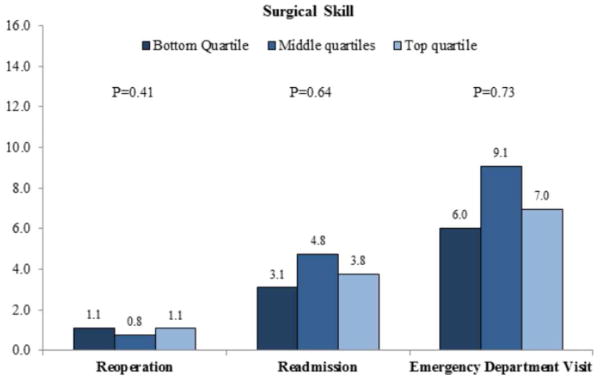

Similarly, there was no relationship found between surgeon skill ratings with gastric bypass and measures of resource utilization after sleeve gastrectomy (Figure 2). Rates of reoperation were low for surgeons of all skill levels and were the same for both the top and bottom quartiles (1.1%). Emergency department visit were also not significantly different across skill levels: top rated surgeons (7.0%), middle (9.1%) and bottom (6.0%) (p=0.73). The rates of hospital readmission were also not significantly different across skill levels: top rated surgeons (3.8%), middle (4.8%), and bottom (3.1%), p=0.64.

Figure 2.

Rates of reoperation, readmission and visits to the emergency department after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, according to quartile of surgical skill.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluates whether peer video ratings of surgical skill for one procedure are correlated with outcomes for another common bariatric operation performed by the same surgeons. We found no relationship between surgeon’s skill ratings for laparoscopic gastric bypass and risk-adjusted outcomes for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. This finding was consistent across several short-term outcomes including complications, reoperations, and readmissions. These findings suggest that peer ratings of surgical skill with one procedure may not translate to other related operations, even those in the same specialty performed by the same surgeons.

In a prior study, we evaluated the relationship between surgical skill and risk-adjusted outcomes for laparoscopic gastric bypass. Using surgeon videos from the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), we found a very strong step-wise relationship between ratings on the modified OSATS instrument and several important outcomes, including overall complications, serious complications, readmissions, and reoperations. 3 Although numerous studies evaluate the relationship between proxies of surgical skill, such as surgeon- and hospital- volume and fellowship training, data from this prior study was the first to link peer video ratings of surgeon skill to patient outcomes directly.

The present study builds on this work and establishes whether surgical skill ratings assessed with one operation are related to outcomes with other related procedures in that surgeon’s practice. Despite comparing two laparoscopic bariatric operations (ostensibly similar procedures) performed by the same surgeons, we found that skill ratings with laparoscopic gastric bypass were not correlated with short-term outcomes for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. This implies that peer ratings of surgical skill are procedure-specific and that programs aimed at assessing and improving surgeon skill for bariatric surgery, and perhaps other complex operations, will need separate evaluations for each type of procedure.

The lack of a relationship between skill with laparoscopic gastric bypass and outcomes with sleeve gastrectomy could be explained in multiple ways. The first explanation is that surgical skill is not generalizable from one operation to another. In other words, optimal outcomes for an operation may depend on procedure-specific skills. For example, optimal outcomes after laparoscopic gastric bypass may be dependent on the skills necessary to perform the gastrojejunostomy or jejuno-jejunostomy (i.e. a gastrointestinal anastomoses), whereas outcomes after sleeve gastrectomy may be dependent on safe and adequate mobilization of the stomach. Although both tasks require some level of skill, they are different types of skill sets (sewing vs. dissecting) that may not translate from one procedure to another.

A second alternative explanation is that surgical skill is not as important for outcomes after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as it is for laparoscopic gastric bypass. Since laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy does not require the surgeon to perform laparoscopic gastrointestinal anastomoses, it may be considered a technically simpler operation that may not be as dependent on advanced skills as with gastric bypass and thus errors may be less likely to manifest into a complication within 30 days of surgery. Instead, it is possible that surgical skill for sleeve gastrectomy has a greater affect on long-term outcomes, such as weight loss or development of reflux at one year. Which of these hypotheses explains our findings is not clear and deserves further study.

It is also worth noting that our evaluation of surgical proficiency in this study does not take into account variations in surgical technique. This is an important distinction to make, as operative technique and surgical skill are different constructs and can both impact the ultimate outcome of an operation.2 While technique involves the specific steps and sequence of events during a procedure (how an operation is done), skill is a measure of a surgeon’s ability to execute these steps (how well an operation is done). It is plausible that a surgeon may perform an inferior operation (from a technique perspective) and yet appear to be highly skilled during video evaluation. For instance, a surgeon performing a sleeve gastrectomy may handle tissue and divide the stomach in a skillful manner but may also fail to perform important steps of the operation (e.g., mobilize the fundus adequately or repair a hiatal hernia when present). Further study evaluating the interaction of surgical skill and technique are necessary to tease out the independent contribution of each.

There are several imitations to our study that should be considered. First, the participation of surgeons was voluntary and may have introduced a selection bias both at the patient and surgeon level. Despite this, patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy had similar demographics and mean perioperative outcomes when compared to the broader group of patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy in the MBSC. This also means that self-selected surgeons in this study were not over- or under-performing when compared to the remaining surgeons in the collaborative. With regard to rating of surgical videos, we did not measure the influence by other members of the surgical team such as assistants, residents, and other surgical staff associated with the procedure being reviewed. A surgeon’s skill may be limited or enhanced depending on their assistant’s skill.10 Nonetheless, the performance of the team was also not measured for our prior study on laparoscopic gastric bypass, which did show a positive association between surgeon skill and outcomes. Another limitation is that this study does not take into account a surgeon’s learning curve or the evolution of their technique. Previous studies demonstrate a substantial learning curve before mastering laparoscopic gastric bypass. 1, 5, 13 It is unclear whether the same learning curve exists for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Between 2006 and 2013 there was rapid rise in the number of sleeve gastrectomy procedures in the state of Michigan.15 During the time of this study, surgeons may have been at different points on their learning curve with regards to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. To account for the effect of year of surgery on complication rates, we controlled for year of surgery in our final risk-adjusted model. However, our data also demonstrates that surgeons with higher skill ratings for gastric bypass were performing a higher volume of bariatric cases overall and had faster mean operative times for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Although this may indicate that these surgeons had overcome their learning curve for sleeve gastrectomy, it appears as though it had no effect on complication rates.

This study has implications for efforts aimed at improving performance and quality with bariatric surgery. The most direct implications are for a recently initiated surgical coaching program in the MBSC. We are implementing a video-based coaching trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that will begin in October of 2015. This program was originally aimed at improving technical skill with laparoscopic gastric bypass. However, with the rapid rise in the use of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and the decline in the use of laparoscopic gastric bypass, we have amended our protocol to include coaching for both procedures. We conducted the present analysis to inform our selection of surgical coaches, which was intended to be based on video skill ratings. This study was critical for informing our coach selection process. Because skill with gastric bypass did not correlate with sleeve gastrectomy, we could not use our existing skill video ratings to select laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy coaches. We thereore selected our sleeve gastrectomy coaches based on their risk-adjusted outcomes with that procedure.

This study has broader implications for other efforts aimed at improving quality using surgical skill ratings. With the prevalent use of minimally invasive techniques that use video, there is significant potential for utilizing video-based skill ratings for assessing competency in surgery and also improving quality. The findings of our study suggest that a surgeon’s skill with one operation may not translate into other similar operations. Thus, skill assessments should focus on individual procedures given the variation in technique, necessary skill sets, learning curves and even instrumentation in some cases. Our study emphasizes the utility of video-based skill assessment for competency when new procedures or innovative devices are introduced into mainstream surgical practices. Instead of relying on day-long or weekend courses that fail to address differences in surgeons’ level of skill, experience or specific learning style, a video-based approach has the ability to identify unique learning gaps and thus offer a personalized approach to improving skill.

CONCLUSIONS

Video-based peer ratings of surgical skill with laparoscopic gastric bypass did not correlate with outcomes for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surgeons with higher skill ratings for gastric bypass had similar outcomes to surgeons with lower skill ratings when evaluating 30-day complication rates with sleeve gastrectomy. These findings suggest that video-based rating of skill with one operation does not predict outcomes of another similar operation. In order to evaluate the impact of surgical skill on outcomes, each procedure requires an independent evaluation of surgical technical proficiency.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by grants to Dr. Dimick from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (RO1 HS023597) as well as the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (RO1 DK101423). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Government.

Footnotes

No disclosures

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ballantyne GH, Ewing D, Capella RF, et al. The learning curve measured by operating times for laparoscopic and open gastric bypass: roles of surgeon’s experience, institutional experience, body mass index and fellowship training. Obes Surg. 2005;15:172–182. doi: 10.1381/0960892053268507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bann S, Khan MS, Datta VK, et al. Technical performance: relation between surgical dexterity and technical knowledge. World J Surg. 2004;28:142–6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7071-z. discussion 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O’Reilly A, et al. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1434–1442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1300625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonrath EM, Dedy NJ, Gordon LE, et al. Comprehensive Surgical Coaching Enhances Surgical Skill in the Operating Room: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2015;262:205–212. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Kadre L, Tinoco AC, Tinoco RC, et al. Overcoming the learning curve of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a 12-year experience. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faulkner H, Regehr G, Martin J, et al. Validation of an objective structured assessment of technical skill for surgical residents. Acad Med. 1996;71:1363–1365. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199612000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez R, Nelson LG, Murr MM. Does establishing a bariatric surgery fellowship training program influence operative outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:109–114. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0860-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenberg CC, Klingensmith ME. The Continuum of Coaching: Opportunities for Surgical Improvement at All Levels. Ann Surg. 2015;262:217–219. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jafari MD, Jafari F, Young MT, et al. Volume and outcome relationship in bariatric surgery in the laparoscopic era. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4539–4546. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krell RW, Birkmeyer NJ, Reames BN, et al. Effects of resident involvement on complication rates after laparoscopic gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin JA, Regehr G, Reznick R, et al. Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. Br J Surg. 1997;84:273–278. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1997.02502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min H, Morales DR, Orgill D, et al. Systematic review of coaching to enhance surgeons’ operative performance. Surgery. 2015;158:1168–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliak D, Ballantyne GH, Weber P, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: defining the learning curve. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:405–408. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8820-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliak D, Owens M, Schmidt HJ. Impact of fellowship training on the learning curve for laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2004;14:197–200. doi: 10.1381/096089204322857555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reames BN, Finks JF, Bacal D, et al. Changes in bariatric surgery procedure use in Michigan, 2006–2013. JAMA. 2014;312:959–961. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reames BN, Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, et al. Hospital volume and operative mortality in the modern era. Ann Surg. 2014;260:244–251. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh P, Aggarwal R, Tahir M, et al. A randomized controlled study to evaluate the role of video-based coaching in training laparoscopic skills. Ann Surg. 2015;261:862–869. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varban OA, Reames BN, Finks JF, et al. Hospital volume and outcomes for laparoscopic gastric bypass and adjustable gastric banding in the modern era. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]