Abstract

Recruitment for large cohort studies is typically challenging, particularly when the pool of potential participants is limited to the descendants of individuals enrolled in a larger, longitudinal “parent” study. The increasing complexity of family structures and dynamics can present challenges for recruitment in offspring. Few best practices exist to guide effective and efficient empirical approaches to participant recruitment. Social and behavioral theories can provide insight into social and cultural contexts influencing individual decision-making and facilitate the development strategies for effective diffusion and marketing of an offspring cohort study. The purpose of this study was to describe the theory-informed recruitment approaches employed by the Jackson Heart KIDS Pilot Study (JHKS), a prospective offspring feasibility study of 200 African American children and grandchildren of the Jackson Heart Study (JHS)—the largest prospective cohort study examining cardiovascular disease among African American adults. Participant recruitment in the JHKS was founded on concepts from three theoretical perspectives—the Diffusion of Innovation Theory, Strength of Weak Ties, and Marketing Theory. Tailored recruitment strategies grounded in participatory strategies allowed us to exceed enrollment goals for JHKS Pilot Study and develop a framework for a statewide study of African American adolescents.

Keywords: Recruitment, African Americans, Adolescents, Cohort studies, Diffusion of innovation, Population studies

Introduction

Several large cohort studies have expanded to pursue studies of the descendants of cohort participants. These offspring studies call attention to intergenerational dimensions associated with a number of social and health issues including aging [1], depression [2–4], violence [5], and cardiovascular disease [6, 7]. Prominent examples include the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS) [8], an offspring cohort study of the Nurses’ Health Study which examined how diet and exercise influences weight changes throughout a person's life, and the Framingham Heart Study that was expanded to include a young adult offspring study, and a third generation cohort to examine cardiovascular risk factors over the life course [9]. Offspring cohort studies are often used for intergenerational examinations of the transmission of behavioral, environmental, physiological, and genetic risk factors associated with chronic diseases.

Recruitment for large-scale cohort studies is typically challenging, particularly when the pool of potential participants is limited to the descendants of individuals enrolled in a larger “parent” study [10]. The increasing complexity of family structures and dynamics can present challenges for recruitment in offspring studies. These issues include the following: greater geographic mobility of family members, increased racial/ethnic diversity, new patterns of immigration and identity reformulation, and changing work and family roles [11]. Few best practices exist to guide effective and efficient empirical approaches to participant recruitment. Accepted recruitment approaches utilize social media platforms, appealing flyers and posters, recruitment videos, media appearances and announcements, and word-of-mouth. In general, these strategies tend to lack theoretical grounding and sufficient tailoring for targeted populations. Even when these efforts are organized into a pre-determined plan, they often lack deep-structure cultural elements considered necessary to enroll and retain racial/ethnic minority group members [12].

Social and behavioral theories can provide insight into social and cultural contexts influencing individual decision-making and facilitate the development strategies for effective diffusion and marketing of an offspring cohort study. The purpose of this study is to describe the theory-informed recruitment approaches employed by Jackson Heart KIDS Pilot Study (JHKS), a prospective offspring feasibility study of African American youth in Jackson, Mississippi. Participant recruitment in the JHKS was founded on concepts from three theoretical perspectives—the Diffusion of Innovation Theory, Strength of Weak Ties, and Marketing Theory. Recruitment for the parent cohort—The Jackson Heart Study—experienced significant challenges [13, 14] which underscored the notion that methods to engage racial/ethnic minority populations in research studies require carefully designed strategies [15]. A pilot study was undertaken to explore challenges associated with recruiting children and grandchildren of JHS participants, and ways to overcome them. This article describes the pilot study experience, highlighting the use of frameworks and theoretical perspectives from the fields of business, communication, and social science. The concepts and strategies described in this manuscript illustrate how theory-based recruitment strategies can improve study enrollment outcomes and lay the groundwork for recruitment in full-scale longitudinal cohort studies conducted in concert with community-based participatory principles.

Brief Overview of the Jackson Heart Study and the Jackson Heart KIDS Pilot Study

The Jackson Heart Study (JHS) is the largest prospective cohort study examining cardiovascular disease (CVD) among an exclusively African American adult population. This single-site, longitudinal, population-based cohort study was designed to prospectively investigate determinants of CVD among African Americans living in the tri-county area (Hinds, Madison, and Rankin counties) of the Jackson, MS Metropolitan Statistical Area. Baseline data collection occurred between September 2000 and March 2004, with two subsequent waves of data collection conducted between 2005–2010 and 2010–2015. Recruitment, sampling, and data collection methods have been described previously [16, 17]. The initial JHS recruitment protocol limited the age range from 35 to 84, but allowed relatives <35 years and >84 years to enroll in order to increase the sample power of the family component of the study [16]. The total cohort at baseline consisted of 5301 African American men and women between the ages of 21 and 94.

The Jackson Heart KIDS (JHKS) Pilot Study was a prospective feasibility study of the children and grandchildren of individuals participating in the JHS. It is one of the few prospective cohort studies linking data from African American children/adolescents with their parents/grandparents to examine sensitive developmental and transition periods for the development of risk factors for subsequent cardiovascular disease. This capability paves the way for analyzing the intertwined biological, behavioral, and social transmissions of risk across generations and to assess intergenerational exposure-disease associations [18].

The aims of the JHKS Pilot Study were to (1) consent, recruit, and enroll 200, 12–19-year-old offsprings (children and grandchildren) of participants in the JHS; (2) collect behavioral and psychosocial measures (dietary intake, physical activity, sleep, and stress), anthropometric measures (height, weight, and waist circumference), and biologic measures (fasting blood glucose and blood pressure) to estimate the prevalence of specific lifestyle factors which may influence the risk for cardiovascular disease in this cohort; and (3) use the resultant data from this pilot study to determine the feasibility of, and to estimate the sample size parameters required for an eventual prospective, longitudinal cohort study of African American youth. The primary outcome measure for the JHKS pilot study was participation in each aspect of the study protocol (e.g., overall participation, response rate to recruitment efforts, completion of psychosocial surveys, and biospecimen donation).

Theoretical Foundation: Diffusion of Innovations and Strength of Weak Ties

Theory has been a key component in science, providing the foundation for the conceptual framework motivating and guiding research studies. Social and behavioral theories have been used to stimulate hypothesis generation and perhaps result interpretation in intervention studies. But, no studies to our knowledge have explicitly use theory to guide participant recruitment strategies. A recent popular publication focusing on the social networks and the transmission of ideas [19] has highlighted two classical theoretical perspectives—Diffusion of Innovation Theory and The Strength of Weak Ties—that can inform and enhance participant recruitment. The Diffusion of Innovation Theory introduced by Rogers [20] is a model that explains the population-level uptake of “innovations”, a term that has been operationalized as an idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by individuals or groups. According to Rogers, diffusion is “the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over a period of time among members of a social system” [20]. Four main elements are seen as central to the diffusion of new ideas including (1) the innovation itself, (2) communication channels, (3) time, and (4) the social system. The innovation considers characteristics, which determine an innovations’ rate of adoption and why certain innovations spread more quickly than others. Effective communication using mass media and interpersonal channels is the second main element. Mass media is seen as more effective in creating knowledge about innovations and interpersonal channels are deemed more effective in forming and changing attitudes towards a new idea and ultimately, the adoption of new ideas based on the viewpoint of salient others. The time dimension is critical to diffusion in three main ways: (1) an innovation-decision process (knowledge formation to attitude development, and an ultimate decision to adopt or reject an idea or behavior); (2) the innovativeness of the potential end user of the new idea; and (3) the rate of adoption, or speed at which an innovation is adopted by a population. The fourth and final element that characterizes the diffusion of new ideas is the social system. Social systems can be formal or informal groups within which an innovation diffuses; typically through group leadership and/or through change agents.

The Strength of Weak Ties introduced by Granovetter [21], is a theoretical extension of Rogers’ framework and identifies interpersonal ties as the channels through which information is transmitted in a social network. Information-carrying connections can be diverse, and Granovetter classified them as strong, absent, or weak [21]. Diffusion is stunted when there are no ties between individuals, and is limited among groups with strong ties. Individuals embedded in networks with strong ties tend to have access to the same information, diminishing the likelihood that this knowledge is discussed within or transmitted to outside groups. It has been suggested that weak ties are responsible for the majority of information transmission because acquaintances often operate in different social networks, thereby facilitating the spread of information among multiple groups of people [21].

The social networks of many African Americans can be profoundly affected by residential segregation as this form of social isolation limits access to social resources including health information [22, 23]. Minimal research has examined the degree to which weak ties exist in African American communities or have implications for study recruitment; however, social network characteristics can be a factor contributing to low study participation among underrepresented groups. Study participation therefore can be viewed as an “innovation” that can spread throughout African American and other underserved communities. These basic tenets of Rogers [20] and Granovetter [21] served as the foundation upon which our recruitment strategies rested.

Target Population and Initial Recruitment Strategy

The JHKS was an offspring study targeting 12–19-year-old children and grandchildren of individuals enrolled in the JHS. Exclusion criteria included medical conditions and medications affecting growth; conditions limiting participation in the assessments (e.g., two or more grades behind in school for reading and writing), and the inability or failure to provide informed consent. All offspring meeting these criteria were eligible to participate, including multiple children from the same family.

The bulk of the study population was expected to be younger than 18 years of age; therefore, recruitment involved contact with parents and grandparents. The sampling frame of parents/grandparents was determined by responses to a question on the JHS personal data—socioeconomic status data form completed during the third wave of data collection. JHS members were asked to identify the number of individuals living with them (or had lived with them in the past year) under the age of 18. Those having at least one person under 18 years of age living with them comprised the pool from which 600 JHS cohort members were randomly selected to receive a letter from JHS and JHKS principal investigators soliciting participation. Recruitment letters provided information about JHKS with a brief eligibility survey to confirm the ages of their children, parental informed consent, and child assent forms. A self-addressed stamped envelope was provided to encourage JHS participants to return the signed completed forms. The brief eligibility questionnaire was designed to (1) collect basic demographic information, (2) assess medical condition and current medications, and (3) report adolescent grade retention in school (two or more grades). Once the eligibility questionnaire, consent, and assent forms were received and evaluated, the potential participant was entered into a database for a baseline telephone interview and scheduled for a clinic visit.

Signs and flyers promoting the JHKS were also placed in the JHS clinic, and staff members were encouraged to share information about the offspring study with JHS participants completing their third wave of data collection. It was expected that these standard recruitment strategies would be effective given the established networks within the parent study; however, our initial efforts produced a small yield. Part of the poor response could be attributed to the fact that the third wave of data collection for the JHS was concluding while the JHKS was starting the recruitment phase, or related to fatigue in a community where research participation is not traditionally embraced. These circumstances prompted us to consider alternate enrollment strategies. It was determined that participant-engaged approaches were needed to meet enrollment goals and we revised recruitment strategies with guidance from contemporary ideas in the business literature.

Theoretical Infusion and Revised Recruitment Strategies

Our revised recruitment strategy also drew from a recent extension of the Diffusion of Innovation and Strength of Weak ideas. Gladwell [19] argues that the spread of information is dependent on the presence of individuals with contacts spanning multiple networks (connectors), communication skills conducive to sharing information via “word of mouth” (mavens), and enigmatic and magnetic personalities that influence others (salesmen) [19]. Consistent with these principles, we hired staff members who were well-known and/or were from respected families in the Jackson community and throughout the state of Mississippi to be the recruitment specialists for the JHKS. An ideal recruitment specialist ideally embodies all of the characteristics of connectors, mavens, and salesmen as exemplified by a myriad of networks in a variety of different social and professional arenas, membership in several community-based organizations, connections with community members, university presidents, and policy makers, eagerness to share information with others, charismatic personality, and ability to positively influence others. These characteristics and skill sets were critical for the successful implementation of the revised recruitment plan.

Our revised recruitment plan was also informed by features of business management such as “marketing”, “sales”, and “ongoing client management” [24]. Table 1 outlines the business-based model undergirded by marketing theory principles upon which we based our modified recruitment strategies. The revised framework includes four domains: (1) building brand values, (2) product and market planning, (3) participant and community engagement, and (4) maintaining engagement; each domain includes three components [24, 25]. These 12 elements are hypothesized to be interdependent; if one aspect is weak, then the entire framework is weak.

Table 1.

Translation of business model components for recruitment

| Component | Description of business model components | Application in the JHS KIDS Study |

|---|---|---|

| 1a. Developing brand values | “Brand values” define what a “brand” “is” and what “it is not” | The “brand” needs to communicate the purpose and importance of the study |

| 1b. Gaining legitimacy and prestige | Research studies, particularly non-intervention trials need to be deemed credible by the community and led by investigators seen as trustworthy | Investigators need to demonstrate professionalism throughout the entire trial process; interaction with funding agencies and respectful relationships with universities, community, and participants |

| 1c. Signaling worthiness | Need to demonstrate to potential participants the value of study engagement relative to the cost of time | Utilize multiple venues to demonstrate the importance of the research questions driving the study and how the findings can have implications for individuals, families, and/or communities |

| 2a. Providing simple complete processes | Learning about research studies, engagement in participant screening, and participating in a study requires energy and time in addition to existing responsibilities and commitments, particularly when engaging with families | Research studies are protocol driven and consent forms often include technical procedures and language that are often foreign to participants. It is essential to train staff, identify roles and responsibilities, and utilize efficient recruitment processes |

| 2b. Devising strategies for overcoming resistance | The length of questionnaires and invasive study measures can create concern for potential participants | Identify which measures may cause concern for participants and develop modifications to data collection procedures that may assuage any apprehensions |

| 2c. Adopting an explicit marketing plan | Critically important to develop formal plans to market the study inclusive of talking points specifically tailored to intended target population and relevant stakeholders | Consistent with the principles of “The Tipping Point”, important to identify mavens, connectors, and salesmen to engage them in the recruitment process and/or serving on a community advisory board |

| 3a. Engaging active sponsors, champions, and change agents | Successful recruitment of participants to a research study requires numerous champions and sponsors who endorse the study and create an environment | Informing salient community-based organizations and disease-specific networks about research studies is an effective way of engaging the entire community and in creating study champions |

| 3b. Delivering a multi-audience, multi-level message | Recruitment messages need to be delivered through various channels of communication and to various audiences | Tailoring recruitment messages and communicating in the language of multiple audiences (e.g., participants, family members, children, etc.) |

| 3c. Achieving buy-in (in public) | Achieving community endorsement for research studies is necessary for social support to participate and continued engaged throughout the trial | From the participant perspective, participation in a research study can be viewed as behavior change. Therefore community support of research studies can help create an encouraging environment necessary for study engagement |

| 4a. Ensuring positive “moments of truth” | Institutions and the research studies they sponsor are often judged by how they manage day-to-day interactions, communications, and challenging issues with community stakeholders | Imperative to develop modalities for communication, dissemination of information, and mechanisms to address questions and/or complaints when recruiting participants. Handle complaints/concerns efficiently and respectfully |

| 4b. Providing frequent positive reinforcement | Retention begins at recruitment; providing positive reinforcement for participants is essential | Demonstration of the benefits of study participation to potential participants the value of their involvement is imperative |

| 4c. Facilitating incorporation into routines | Participants actively work on behalf of the study to ensure success. | Participants are ambassadors for the study, and actively engages in participant recruitment. |

Building Brand Values

A nine-member community advisory board (CAB) was comprised of retired teachers, clergy, pediatrician, a member of the JHS, high school students, and a practicing attorney was established. This group was charged with providing assistance to the study investigators regarding community navigation, “building brand values,” and study recognition throughout the greater Jackson area. They provided critical feedback in the development and placement of the JHKS logo in community settings. The logo design was intended to convey the subject matter of the study, the intergenerational focus, and the name of the study placed at the perimeter of the artwork.

Building credibility and becoming an integral part of the Jackson community was of paramount importance to the JHKS investigative team. As a consequence, opportunities to serve families in the greater Jackson area were mechanisms to provide value to the community and potential participants. Using anecdotal information and support from the CAB, an interactive family-based health fair was developed called “Family-a-Fair.” This event was held during the summer months and permitted over 400 parents and children to engage in educational and interactive health-promotion activities in a family-oriented environment.

The “Family-a-Fair” included vendor-based health fair with screenings and informational materials, family services, healthy cooking demonstrations with area chefs, reading games, movie showings, physical activities (e.g., Zumba, line dancing, field-day activities), and separate physical activity demonstrations by senior citizens and children. Door prizes and drawings were held, as well as book give-a-ways. The events were held in collaboration with community health centers, allied health schools, public libraries, social service organizations, and local and state policymakers. Information about the JHKS study was offered, and study staff members were available to answer any questions. Over 50 interested families provided their contact information for subsequent follow-up from the recruitment staff.

Product and Market Planning

Consistent with the revised recruitment approach based on the business model (Fig. 1), we worked with the CAB to develop an explicit marketing plan to enhance awareness of the JHKS within the JHS Cohort and throughout the general community. In an effort to accomplish these goals, the CAB decided that each board member should discuss the JHKS with at least ten individuals in the Jackson community using collaboratively developed talking points. Board members shared their experiences in making community contacts during regularly scheduled meetings.

Fig. 1.

JHKS business model adopted from Francis et al. [24]

Another method to reach potential participants was to publicize the JHKS through two annual community events established within the JHS: the “Celebration of Life” and a “Birthday Celebration” held for study participants. The former event was designed as a community participatory event for JHS cohort members to celebrate the lives and legacies of African American families, and to highlight the importance of the JHS and the latter is an annual event to celebrate the anniversary of the JHS [26]. Presentations about the JHKS were delivered by the JHS principal investigator at both of these events. These presentations were well received and fueled a longstanding interest in an offspring study (Personal communication, PI JHS, December 2013).

Participant and Community Engagement

Community engagement and support for research studies has been shown to be an essential element for successful participant recruitment, engagement, and ultimately retention [15]. As a consequence, care was taken to broadly inform schools and community-based organizations (e.g., libraries, boys and girls clubs, after-school programs, etc.) who work with children about the JHKS. Creating community awareness, interest, and support for research participation is greatly enhanced when multiple stakeholders feel included and involved.

Prior studies with participants from at least two generations have suggested that multi-audience and multi-level messages were required to recruit participants into research studies; messages that engage both parents/grandparents and children [27–29]. Parents and/or grandparents who were participants in the JHS and 12–19-year-old offspring of cohort members were the main target audiences of JHKS recruitment messages. Study aspects of most importance to this group included the importance of the topic of the study, time commitment required, investigators involved, benefits of participating, dissemination of individual findings, and location of the study were important to parents and grandparents. Conversely, adolescents were interested in the incentives provided, study measures, and parental approval of the study. Recruitment materials provided to both parents and adolescents were designed to convey information regarding each of these issues in a pithy, easy-to-understand, and eye-catching manner.

Maintaining Engagement

Studies have shown that successful retention begins at recruitment with competent study staff who can encourage, engage, and motivate participants [30]. Therefore, the provision of comprehensive training for study staff, inclusive of mechanisms for handling participant complaints or issues encountered during study participation is essential. It is also important that staff training engenders loyalty, dependability, and trust-worthiness because individuals who recruit and collect data are critical elements of a strong study infrastructure. In an effort to accomplish this goal, we conducted extensive training for the recruitment and data collection of the JHKS staff. The project coordinator, an experienced interventionist and exercise scientist with a master's degree, conducted a 16-h, 2-day training. Training elements included, recruitment, elevator pitches to explain the study to potential participants, survey and anthropometric data collection. Two experienced nurses with strong ties to the JHS conducted training on the collection of blood pressure using automated blood pressure devices. Before entering the field, study staff members were certified in recruitment and data collection based on a brief written examination and demonstrated competency in collecting the anthropometric and blood pressure measures.

Recruitment Outcomes and Observations

Our goal for the JHKS Pilot Study was to recruit 200 children and/or grandchildren of JHS cohort members. Table 2 reports demographic characteristics for the 212 adolescent participants ranging in age from 12 to 19 years of age, with a mean age of 15.2 years; 49 % were males. The gender parity among adolescent participants was thought to be a function, in part, of families bringing in multiple children as 149 separate families were represented in the sample (106 parent/child families and 43 grandparent/grandchild families). We met our recruitment goal and had a waiting list of families interested in participating in the study at the end of the enrollment period. Recruitment took place over a total of 6 months, as participant enrollment was interrupted due to operational changes in the parent study. We were unable to calculate participant yield vs those who were contacted because of the minimal response to the original recruitment letters and the nature of the revised recruitment approaches did not permit an assessment of participant reach.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| Index parent/grandparent characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Parents [% (n)] | 72 % (110) |

| Grandparents [% (n)] | 28 % (43) |

| Sex | |

| Female [% (n)] | 88 % (134) |

| Male [% (n)] | 12 % (19) |

| Adolescents characteristics | |

| Age (years) [mean (sd)] | 15.2 (2.2) |

| Sex | |

| Females [% (n)] | 51 % (107) |

| Male [% (n)] | 49 % (105) |

Note: Some parents/grandparents can be linked to multiple adolescents in the study

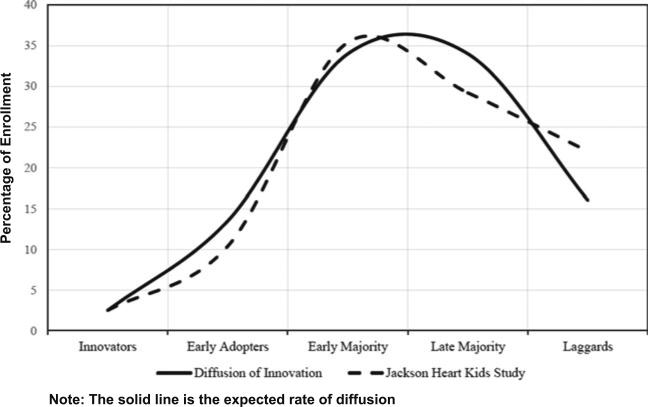

Exceeding our recruitment goals was notable, especially given the challenges associated with the conclusion of wave 3 in the JHS. Interestingly, the enrollment pattern in the JHKS Pilot Study was strikingly similar to the adoption pattern presented in the Diffusion of Innovation Theory. Rogers [20] suggests that the adoption of an idea or a behavior like research study enrollment among an underrepresented group gains momentum and diffuses through a population or system over time. The pattern of behavior uptake introduced by Rogers resembles a bell curve and depicts five classifications associated with diffusion. The categories associated with the uptake of new ideas or behaviors are innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards (Table 3).

Table 3.

Consumer types based on Rogers theory of the Diffusion of Innovation

| Consumer type | Description |

|---|---|

| Innovators | Adventurous and interested in new ideas; require minimal persuasion to try new products or consider new ideas |

| Early adopters | Opinion leaders who enjoy change opportunities; freely share experiences and views about new ventures and products with others |

| Early majority | Adopt new ideas before the average person; typically require evidence about effectiveness or benefit of the innovation prior to adoption |

| Late majority | Skeptical of change; adopt innovations after widespread acceptance and uptake by the majority population |

| Laggards | Traditionalists; very conservative |

Source: [20]

Figure 2 illustrates the relative congruency between the uptake of recruitment efforts in the JHKS Pilot Study compared to the standard diffusion adoption curve introduced by Rogers [20]. Individuals who responded quickly to our initial recruitment mailing and enrolled in the study within 2 weeks were considered “innovators.” Early innovators readily responded to the recruitment specialist and required minimal additional information about the trial to make a decision to participate. Those classified as “early majority’ and “late majority” responded to our outreach efforts with the “Family-a-Fair” events and other marketing efforts. Additional information about the benefits of the study, raffles, and alerts regarding the end of the recruitment period were needed to appeal to the last group of study enrollees.

Fig. 2.

JHKS enrollment and diffusion of innovation curve

Discussion

Participant recruitment for research studies can be difficult. The challenges associated with recruitment can be compounded when attempting to engage members of vulnerable populations who have been disproportionately underrepresented in research studies. This situation can not only exacerbate health disparities but also creates a participation disparity in research and clinical trials [31]. The JHS is a unique study in which the entire cohort is comprised of African American adults who reside in the general metropolitan area of Jackson, Mississippi.

The JHS has been highly regarded for its potential to provide insight into the early onset and accelerated progression of cardiovascular diseases. The JHS was not originally designed to include a child and adolescent offspring cohort, and the concept for, and implementation of the JHKS study was initiated near the conclusion of the active data collection phase. It was necessary to develop innovative strategies to identify and contact families with age-eligible children, create and communicate a brand for the study, and successfully recruit 12–19-year-old children and grandchildren of JHS members into the study. Our revised recruitment strategy was grounded in the cornerstones of social network analysis (i. e., Diffusion of Innovation and Strength of Weak Ties) and contemporary marketing ideas from the business literature applied to clinical trials. Once implemented, these modifications led to a robust response from the JHS participants that allowed us to exceed enrollment goals for the JHKS Pilot Study and develop a framework for a statewide study of African American adolescents.

The experiences associated with the recruitment phase of the JHKS Pilot Study provide some insights worth noting. Research study participation is a human behavior that is influenced by a number of social and environmental factors. Social and behavioral theories can be valuable tools because they help investigators have a greater understanding of the targeted population, thereby allowing them to anticipate barriers to recruitment and to leverage factors encouraging study participation. Social networks have been critical for the survival of African American and other vulnerable communities in the USA [32–34] and continue to be vehicles through which our target population receives and evaluates information. The integration of classic and contemporary social network theories was fruitful for our recruiting efforts, as we were able to establish trust within the JHS cohort and reach eligible families with adolescents between 12 and 19 years of age.

Social and behavioral theories can enhance enrollment among groups underrepresented in research studies; however, the effectiveness of theory-informed recruitment rests upon community engagement practices. The relationship between an academic institution and vulnerable communities is often strained because of legacies of discrimination [35] or dubious scientific practices [36, 37]. It is important for study investigators and staff members to significantly and sincerely invest in the communities targeted for recruitment. These efforts increase the likelihood that positive information is disseminated through social networks, thereby allowing them to meet recruitment goals in a timely manner. A theoretically and culturally grounded approach has the potential to reduce implicit biases and to have an even greater impact on traditionally disenfranchised minority groups such as African Americans.

This study highlights the importance of social and behavior theory for research recruitment. Additional studies are needed to expand the evidence base for the development of culturally appropriate and respectful recruitment strategies targeting underserved and underrepresented groups for research participation. Results from our study lay the foundation for the inclusion of social and behavior theories as components that can bolster the effectiveness of recruitment strategies targeting populations considered hard to reach.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health (Prime Award Number 1 CPIMP091054-04) to University of Mississippi Medical Center's Institute for Improvement of Minority Health and Health Disparities in the Delta Region and career development awards from NHLBI to Jackson State University (1 K01 HL88735-05—Bruce). The authors thank Ms. Lovie Robinson, Dr. Gerrie Cannon Smith, Dr. London Thompson, Ms. Ashley Wicks, Rev. Thaddeus Williams, and Mr. Willie Wright for their support of this study.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest Dr. Beech, Dr. Bruce, Mrs. Crump, and Ms. Hamilton have no financial relationships with the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health (Prime Award Number 1 CPIMP091054–04) or the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1 K01 HL88735–05) and declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

References

- 1.Lowenstein A, Katz R, Biggs S. Rethinking theoretical and methodological issues in intergenerational family relations research. Ageing and Society. 2011;31(7):1077–83. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opoliner A, Carwile JL, Blacker D, Fitzmaurice GM, Austin SB. Early and late menarche and risk of depressive symptoms in young adulthood. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(6):511–8. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0435-6. doi:10.1007/s00737-014-0435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Wypij D, Lightdale JR, Austin SB. Sexual orientation and functional pain in U.S. young adults: the mediating role of childhood abuse. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054702. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts AL, Rosario M, Slopen N, Calzo JP, Austin SB. Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization, and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: an 11-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(2):143–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.006. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jun HJ, Corliss HL, Boynton-Jarrett R, Spiegelman D, Austin SB, Wright RJ. Growing up in a domestic violence environment: relationship with developmental trajectories of body mass index during adolescence into young adulthood. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(7):629–35. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.110932. doi:10.1136/jech.2010.110932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das RR, Seshadri S, Beiser AS, Kelly-Hayes M, Au R, Himali JJ, et al. Prevalence and correlates of silent cerebral infarcts in the Framingham offspring study. Stroke. 2008;39(11):2929–35. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.516575. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.516575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankel DS, Meigs JB, Massaro JM, Wilson PW, O'Donnell CJ, D'Agostino RB, et al. Von Willebrand factor, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham off-spring study. Circulation. 2008;118(24):2533–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.792986. doi:10.1161/ CIRCULATIONAHA.108.792986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomeo CA, Field AE, Berkey CS, Colditz GA, Frazier AL. Weight concerns, weight control behaviors, and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 1999;104(4 Pt 1):918–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.4.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahmood SS, Levy D, Vasan RS, Wang TJ. The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):999–1008. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61752-3. doi:10. 1016/S0140-6736(13)61752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Splansky GL, Corey D, Yang Q, Atwood LD, Cupples LA, Benjamin EJ, et al. The third generation cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart Study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(11):1328–35. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm021. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonucci TC, Jackson JS, Biggs S. Intergenerational relations: theory, research, and policy. Journal of Social Relations. 2007;63(4):679–93. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuqua SR, Wyatt SB, Andrew ME, Sarpong DF, Henderson FR, Cunningham MF, et al. Recruiting African-American research participation in the Jackson Heart Study: methods, response rates, and sample description. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4 Suppl 6):S6-18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wyatt SB, Diekelmann N, Henderson F, Andrew ME, Billingsley G, Felder SH, et al. A community-driven model of research participation: the Jackson Heart Study Participant Recruitment and Retention Study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(4):438–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor HA., Jr The Jackson Heart Study: an overview. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4 Suppl 6):S6-1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor HA, Jr, Wilson JG, Jones DW, Sarpong DF, Srinivasan A, Garrison RJ, et al. Toward resolution of cardiovascular health disparities in African Americans: design and methods of the Jackson Heart Study. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4 Suppl 6):S6-4–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):285–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gladwell M. The tipping point: how little things can make a big difference. Little, Brown and Company; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. The Free Press; New York: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granovetter M. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;78:1360–80. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berkman L, Clark C. Neighborhoods and networks: the construction of safe places and bridges. In: Kawachi I, Berkman L, editors. Neighborhoods and health. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. pp. 288–302. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson WJ. When work disappears: the world of the urban poor. Vintage Books; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis D, Roberts I, Elbourne DR, Shakur H, Knight RC, Garcia J, et al. Marketing and clinical trials: a case study. Trials. 2007;8:37. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-37. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-8-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald AM, Treweek S, Shakur H, Free C, Knight R, Speed C, et al. Using a business model approach and marketing techniques for recruitment to clinical trials. Trials. 2011;12:74. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-74. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-12-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson Heart Study . JHS heartbeat. Jackson Heart Study; Jackson, MS: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berry DC, Neal M, Hall EG, McMurray RG, Schwartz TA, Skelly AH, et al. Recruitment and retention strategies for a community-based weight management study for multi-ethnic elementary school children and their parents. Public Health Nurs. 2013;30(1):80–6. doi: 10.1111/phn.12003. doi:10.1111/phn.12003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berry DC, Schwartz TA, McMurray RG, Skelly AH, Neal M, Hall EG, et al. The family partners for health study: a cluster randomized controlled trial for child and parent weight management. Nutr Diabetes. 2014;4:e101. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2013.42. doi:10.1038/nutd.2013.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui Z, Seburg EM, Sherwood NE, Faith MS, Ward DS. Recruitment and retention in obesity prevention and treatment trials targeting minority or low-income children: a review of the clinical trials registration database. Trials. 2015;16:564. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1089-z. doi:10.1186/s13063-015-1089-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penckofer S, Byrn M, Mumby P, Ferrans CE. Improving subject recruitment, retention, and participation in research through Peplau's theory of interpersonal relations. Nurs Sci Q. 2011;24(2):146–51. doi: 10.1177/0894318411399454. doi:10.1177/0894318411399454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beech BM, Goodman M. Race and research: perspectives on minority participation in health studies. American Public Health Association; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dittmer J. Blacks in the new world. University of Illinois Press; Champaign, IL: 1995. Local people: the stuggle for civil rights in Mississippi. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dittmer J. The good doctors: The medical committee for human rights and struggle social justice in health care. Bloombury Press; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McAdam D. Freedom summer. Oxford University Press; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Board of Health Sciences Policy. Institute of Medicine . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. National Academies Press; Washington, D. C.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones JH. Bad blood: the Tuskegee syphilis experiment: a tragedy of race and medicine. Free Press; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Washington HA. Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on black Americans from colonial times to the present New York: doubleday. 2007 [Google Scholar]