Abstract

Background

Herein we describe a small-diameter vascular graft constructed from rolled human amniotic membrane (hAM), with in vitro evaluation and subsequent in vivo assessment of its mechanical and initial biological viability in the early post-implantation period. This approach for graft construction allows for customization of graft dimensions, with wide-ranging potential clinical applicability as a non-autologous, allogeneic, cell-free graft material.

Methods and Results

Acellular hAM were rolled into layered conduits (3.2-mm diameter) that were bound with fibrin and lyophilized.

In vitro analysis

Constructs were seeded with human smooth muscle cells (SMC) and cultured under controlled arterial hemodynamic conditions. SMC were shown to adhere to, proliferate within, and remodel the scaffold over a four-week culture period. At the end of the culture period, there was histologic and biomechanical evidence of graft wall layer coalescence.

In vivo analysis

The acellular hAM conduits were surgically implanted as arterial interposition grafts into the carotid arteries of immunocompetent rabbits. Grafts demonstrated patency over four weeks (n=3) with no hyperacute rejection or thrombotic occlusion. Explants displayed histologic evidence of active cellular remodeling, with endogenous cell repopulation of the graft wall concurrent with degradation of initial graft material. Cells were shown to align circumferentially to resemble a vascular medial layer.

Conclusions

The vascular grafts were shown to provide a supportive scaffold allowing for cellular infiltration and remodeling by host cell populations in vivo. Using this approach, “off-the-shelf” vascular grafts can be created with specified diameters and wall thicknesses to satisfy specific anatomical requirements in diverse patient populations.

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of mortality worldwide, with arterial bypass grafting representing an important therapeutic intervention.1 While autologous arteries have the highest success rates as bypass grafts, inessential and non-diseased arteries are in short supply, such that the need for enduring vascular replacements remains an urgent clinical priority.2,3 Tissue-engineering by self-assembly (TESA) represents a strategy for vascular graft assembly that utilizes autologously-derived cells to secrete ECM sheets that can subsequently be rolled into vascular constructs.4 Motivated by the clinical successes of this approach in non-urgent procedures, herein we investigate a similar, yet expeditious, approach to develop a rolled vascular graft that could be available on an emergent basis for allogeneic use.5

Similar to the pioneering TESA cell-sheet technology described by Dr. L'Heureux et al., thin ECM sheets of human amniotic membrane (hAM) can be rolled around a supportive mandrel into multilayered wall conduits.4,6 Owing to its perinatal origin, the human amnion does not elicit an adverse immune response even in its native, cellular form, making it an ideal matrix for regenerative therapies.7,8,9 The hAM has the additional advantage of abundant availability, and has been clinically used in other applications with success for over a century.10-13 While a cell-mediated fusion of the layers has proven successful in preliminary studies, this study investigated the use of freeze-drying in conjunction with a fibrin sealant to bind adjacent layers.6,14 Without the need for pre-population with autologous cells, the conduits would be readily available, easily transportable, and storable extended time periods.

With a rolling approach, vascular graft dimensions can be prepared to custom specification. An acellular graft should be able to withstand surgical implantation, be tolerated by the host, and support host cell remodeling of the scaffold into vascular tissue. As such, our research question was three-fold: 1) can a vascular graft derived from decellularized human amnion mechanically endure initial surgical implantation into arterial systemic circulation, 2) will such a vascular graft survive into the early postoperative period without eliciting hyperacute rejection and/or thrombosis, and 3) will such a vascular construct demonstrate histologic evidence of early cellular remodeling reminiscent of native vascular architecture.

METHODS

Experimental Design

Human amniotic membranes were decellularized and rolled into tubular conduits for in vitro and in vivo investigation. For preliminary study of early graft remodeling in vitro, grafts were seeded with human smooth muscle cells and cultured for 28 days to assess the influence of pulsatile fluid forces on cell-mediated changes to scaffold biochemical and biomechanical composition. For the in vivo study, the hAM grafts were implanted in rabbit carotid arteries over a 4-week time period to assess initial host tolerance of the graft as well as early cellular remodeling. Study design and methods conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85-23). This study was performed after obtaining approval from the University of Florida's Animal Care Services (ACS) and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (#VA89, VA #0028).

Graft Preparation

Human amniotic membranes were separated from the chorion by blunt dissection and decellularized as previously described using sodium dodecyl sulfate and DNAse I.14,15 hAM ECM was cut into 60-mm × 60-mm sheets, rehydrated with 50 mg/mL fibrinogen and rolled around 3.2-mm outer diameter tubing. The resultant six-layered hAM scaffolds were then treated with thrombin to catalyze the formation of fibrin and freeze-dried. Samples were then washed in successive PBS rinses (5, 15, 40 min, 1 hour, 6 hours) prior to a final freeze-drying step. Samples were rehydrated sterile PBS 30 min prior to implantation.

In Vitro Studies

Cell Expansion and Culture

Primary human smooth muscle cells were explanted from umbilical arteries and cultured at subconfluent densities as previously described.14 Based on previous work that optimized cell seeding density (unpublished), the ablumenal surface of the graft was seeded at a density of 600 cells/mm2.14 Dynamic culture was performed in custom bioreactors connected within a dual circuit perfusion system. Two peristaltic pumps were used to independently control the lumenal and ablumenal flow circuits. Lumenal flow rate and pressure were ramped over the first ten days to reach a final maximum pressure of 120 mmHg and pulse rate of 1 Hz, while the ablumenal flow was maintained at 5 mL/min throughout the duration of the four week culture period.

Biochemical and Histological Analysis

Samples were digested using 125 μg/mL Papain (Spectrum, Gardena, CA) for 24 h at 60 °C. SMC proliferation was assessed, via quantification of total construct DNA, using the Quanti-iT PicoGreen DNA assay (Invitrogen, Oregon, USA). GAG content was assayed using dimethylmethylene blue (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis MO, USA).15,16,17 Acellular scaffolds were imaged under SEM as previously reported.14 Samples were embedded in Neg-50 media, frozen, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard protocols.

Biomechanical Analysis

Tensile properties were assessed using an Instron uniaxial testing rig (Model 5542 Norwood, MA with Version 2.14 software) as previously reported.14 Burst pressure was determined using a modified syringe pump to increase lumenal pressure within the 6-cm long scaffolds until failure. The distal end of each construct was sealed with a pressure transducer immediately downstream of the scaffold to determine the ultimate pressure at failure. Each test was digitally recorded to measure vessel distention at a given pressure using NIH ImageJ software.

In Vivo Studies

Graft Implantation

Acellular grafts were prepared from human amnion as described above to match the inner diameter and wall thickness of New Zealand White rabbit carotid arteries (approximately 3.2-mm and 300-μm, respectively). Scaffolds were implanted in the common carotid arteries of Male New Zealand White rabbits using an anastomotic cuff technique as previously described, with polyethylene cuffs (3.0–3.5 kg; n = 3).18 The four-week length of implantation was selected following preliminary evaluation of the extent of graft remodeling after one week of implantation (n=1).

All operations lasted approximately 15 minutes on average, used aseptic technique and were performed under an operating microscope. Prior to graft implantation, 1,000 units of IV heparin were administered. Anesthesia was initiated by 30.0-mg/kg IM ketamine hydrochloride and maintained by inhaled isoflurane (2.5–3.0%) through endotracheal intubation. Perfusion through the carotid arteries was recorded using an ultrasonic transducer (model T106, probe 2SB; Transonic Systems Inc, Ithaca, NY). Neurological assessment of each rabbit appraised potential cerebrovascular compromise. No post-surgical medical therapy was necessary.

Histological Analysis

Explanted tissue was fixed in 10% formalin, paraffin embedded and sectioned. Samples were stained with Masson's Trichrome using standard histological techniques. Mid-graft sections were used to evaluate the thickness of the wall. Wall thickness was measured using NIH ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean values +/− standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments (n=3) for biochemical assays and at least five independent experiments (n=5) for biomechanical tests. Statistical analysis was performed using a student t-test with significant differences corresponding to a P<0.05 (confidence level ≥95%).

RESULTS

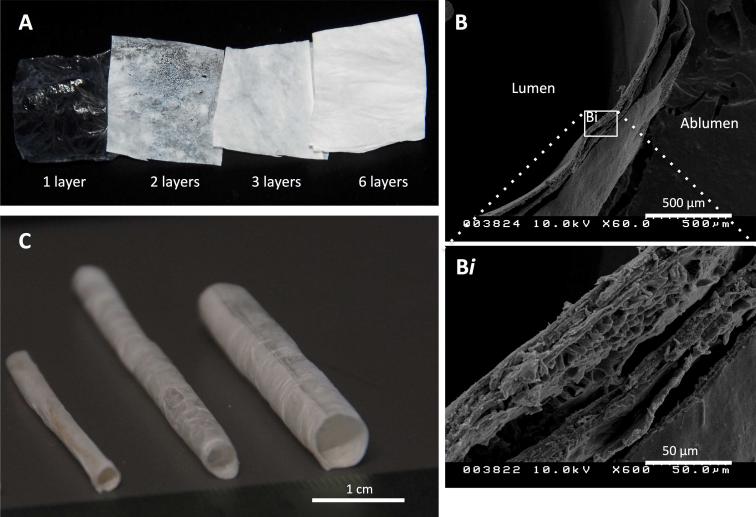

Figure 1A shows the change in gross appearance between a single dry ECM sheet and laminated sheets of increasing thicknesses. Initial durability testing verified acellular grafts withstood 24 hours of 1 Hz pulsatile perfusion culture at approximately 80 to 120 mmHg without delamination and had burst pressures of 1430 +/− 250 mmHg. Cross-sectional views of the rolled scaffolds under SEM display the smooth surface of the amniotic basement membrane that forms the ablumenal surface of the tubular scaffold (Figure 1B). Association of adjacent layers that form the six-layered wall can be observed at a higher magnification (Figure 1Bi). As an example of variation in rolled geometry, scaffolds with internal diameters (ID) of 3.2 mm, 4.2 mm and 6 mm are shown in Figure 1C. Figure 2A details the overall approach of graft preparation, with panel 2Aiv showing a scaffold in a bioreactor for in vitro analysis.

Figure 1. ECM scaffold characteristics.

Laminated amnion-derived ECM scaffolds allow tailored geometries for guided tissue regeneration. Flat sheets of lyophilized sheets of amnion with increasing number of layers are visualized by increasing opacity (A). SEM cross-section of a scaffold wall comprised of six lyophilized layers shows the degree of layer-to-layer interaction (B), better visualized with 10x magnification (Bi). Three tubular scaffolds of different geometries, from left to right, with internal diameters (ID) of 3.2 mm, 4.2 mm and 6 mm (C).

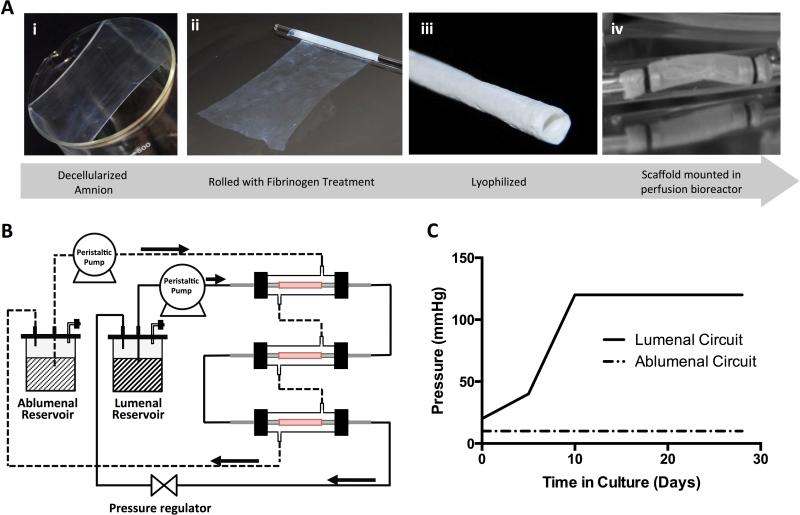

Figure 2. Graft preparation and in vitro conditioning.

Decellularized amniotic membranes (Ai) were freeze-dried, followed by rehydration with fibrinogen (Aii). Scaffolds were then rolled and thrombin was applied to catalyze the cross-linking. Lastly, the scaffolds were freeze-dried (Aiii). Scaffolds were mounted in bioreactors (Aiv) prior to seeding. Constructs mounted in bioreactors were connected in the dual-perfusion circuit as shown schematically (B). An incremental lumenal flow regime was applied to allow time for initial cellular adhesion to the scaffold surface. As the flow rate was increased, the check valve was used to regulate the pressure of the flow circuit such that a maximum lumenal pressure of 120 mmHg was obtained 10 days following cell seeding. The ablumenal flow was held constant at 5 mL/min throughout the study (C).

In Vitro Studies: Cell Repopulation and Early Graft Remodeling

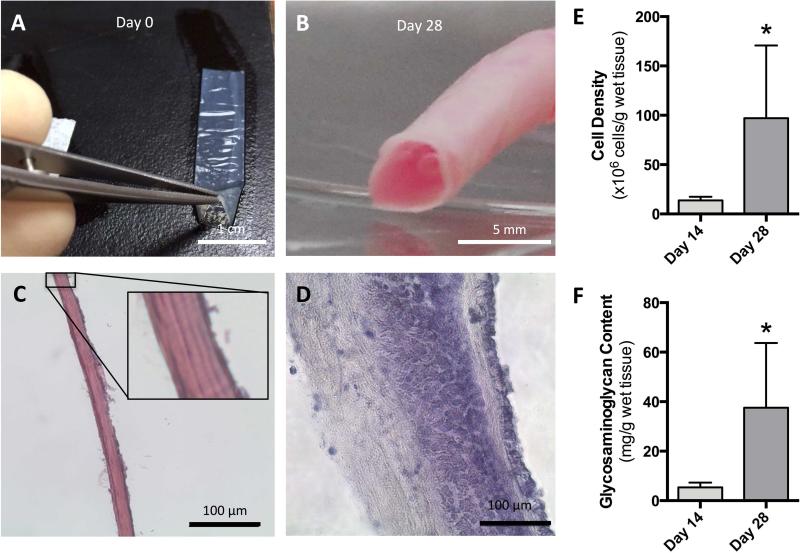

The schematic diagram of the dual-perfusion circuit is shown in Figure 2B. A downstream pressure regulator was used to maintain a maximum lumenal pressure of 120 mmHg from day 10, as shown in Figure 2C. Upon initial rehydration the translucent acellular tubular scaffolds collapse, (Figure 3A) however, after four weeks of dynamic culture the construct is visibly opaque and able to maintain a tubular conformation without additional mechanical support (Figure 3B). A histological assessment of the acellular scaffold (Figure 3C) and the dynamically stimulated construct (Figure 3D) shows that the initially laminated wall coalesced after 28 days in perfusion culture. Cell densities and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content each displayed statistically significant increases between days 14 and 28. Cell density increased seven-fold from 13.7 to 97 million cells per gram of the cultured construct and GAG content increased from 5.4 to 37.6 mg/g of wet tissue in the final two weeks of culture (Figures 3E and 3F, respectively).

Figure 3. In vitro morphological and biochemical evaluation.

Hydrated, acellular scaffolds were translucent in appearance and collapsed upon rehydration (A), but after four weeks in dynamic perfusion culture constructs were grossly opaque (B). Histological sections of the initial laminated acellular scaffold wall (C; with high powered view inset), was shown to coalesce following 28 days in perfusion culture (D; hematoxylin-eosin). A significant 7-fold increase in cell density (from 13.7 to 97 million cells per gram of wet tissue from the cultured graft) occurred between 14 and 28 days of culture (E). Similarly, glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content increased significantly from 5.4 to 37.6 mg/g of wet tissue between days 14 and 28 (F).

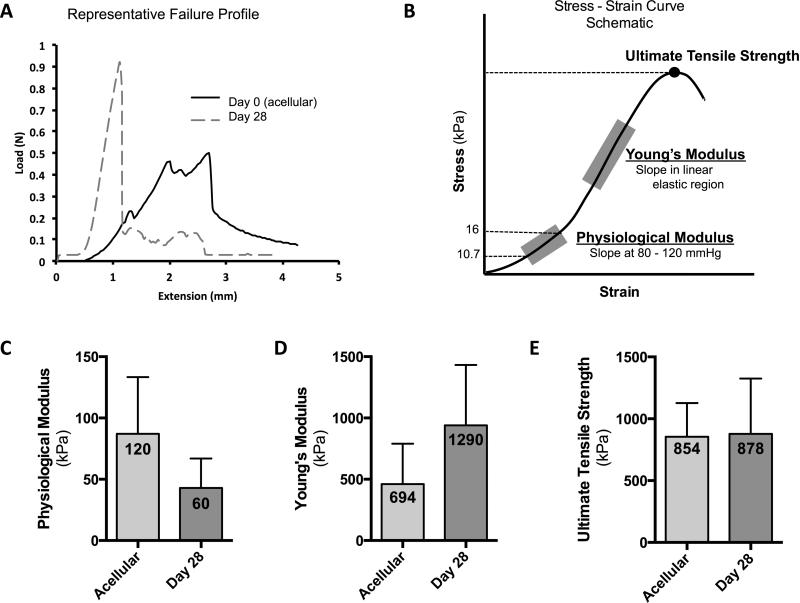

Remodeling of the constructs’ laminated walls over the 4-week perfusion culture period results in changes in the representative load-extension profile as compared to acellular grafts, Figure 4A. Constructs displayed increased modulus values (stiffer) with a single fracture point when tensioned to failure after four weeks of perfusion culture. Figure 4B is a schematic of a stress-strain curve to demonstrate the regions of the curve from which the mechanical properties were derived. After 28 days of perfusion culture, constructs maintained the initial scaffolds tensile properties with trends towards a decreasing physiological modulus (from 120±54.6 kPa to 60±26.0 kPa, Figure 4C) and an increasing Young's modulus (from 694±227 kPa to 1290±593 kPa, Figure 4D). No significant changes were noted in the scaffolds’ ultimate tensile strength from 854±272 kPa as an acellular scaffold to 878±447 kPa by the conclusion of the study at 28 days (Figure 4E).

Figure 4. Biomechanical properties of in vitro constructs.

Representative failure profile of graft ringlets tensioned until failure show typical failure profiles of acellular grafts displayed a lower failure point than constructs cultured for four weeks in pulsatile perfusion bioreactors. Constructs cultured for 28 days displayed a distinct failure point (A). Biomechanical parameters were calculated from the regions highlighted in a stress-strain curve schematic (B). Biomechanical analysis of grafts in vitro showing the physiological modulus (C), Young's modulus (D), and the ultimate tensile strength (E) of the acellular scaffolds (before culture) and after 28 days of biomimetic culture with SMC.

In Vivo Studies: Ultrasound and Histomorphic Evaluation

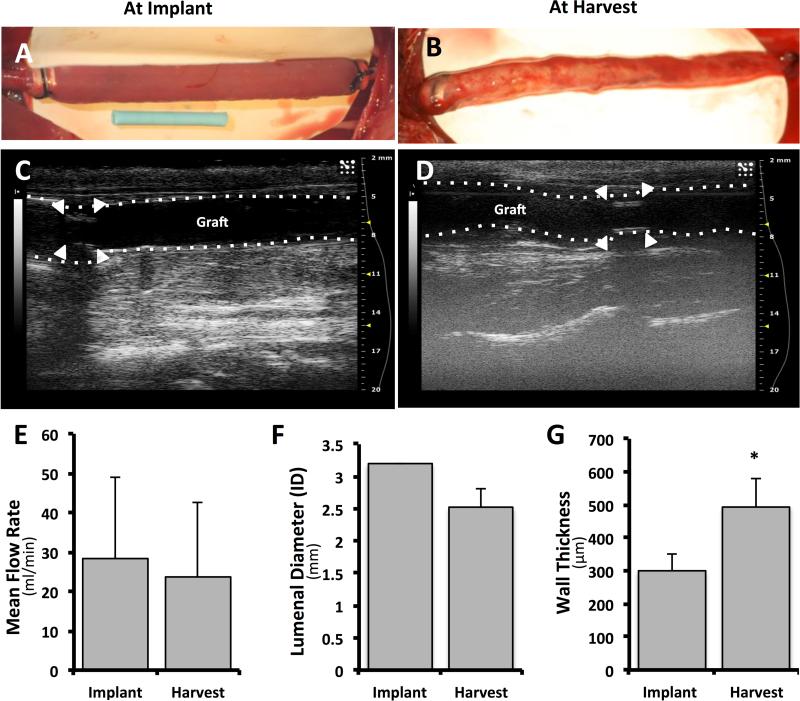

Acellular human-derived grafts were interposed into the carotid arteries of four New Zealand white rabbits.18 Grafts were described by the surgeons to have acceptable handling properties. Complete reperfusion was visualized grossly and confirmed by ultrasound, Figure 5A and 5C. No erratic behavior was observed in the neurological assessments and there was no statistically significant change in animal weight. No acute rejection occurred and no thrombotic response was detected by ultrasound. At day 28 explantation, one graft exhibited non-occluding thrombus formation at the distal anastomosis while the other two appeared grossly patent.

Figure 5. In vivo pilot study.

Human amnion-derived grafts were interposed in rabbit carotid arteries. Gross morphology: longitudinal view of a representative graft at implantation (A) and at harvest 28 days later (B). At explantation, grafts were surrounded by a loose thin cover of highly vascularized tissue. The blue tubing in B represents a 12.6 mm length. Analysis by Doppler ultrasound: representative longitudinal views of grafts at implantation and harvest (C and D, respectively) reveal the patency of the graft after 4 weeks. The white arrowheads indicate the location of the polyethylene cuffs. Mean flow rate at implantation (‘Implant’) and after 28 days (‘Harvest’) does not change significantly (E). The internal diameter (ID) of the lumen decreased, but not significantly (F) but the average wall thickness was significantly increased (G).

Gross appearance of the graft in the longitudinal view is also shown immediately prior to explant, Figure 5B. At explantation, grafts were enveloped by a thin, highly vascularized tissue, and displayed pulsation patterns synchronous with the adjacent native carotid artery. Doppler ultrasound at explant showed graft patency at four weeks (Figure 5D). No statistically significant changes were noted in average local blood flow rate through the graft over the course of the implantation (28±21 mL/min at implantation and 23±19 mL/min at four weeks; Figure 5E). The mean internal lumenal diameter decreased, without statistical significance, from 3.2 to 2.5 mm and the wall thickness of the graft at the midpoint increased significantly from approximately 300 to 500 μm (Figure 5, F and G respectively).

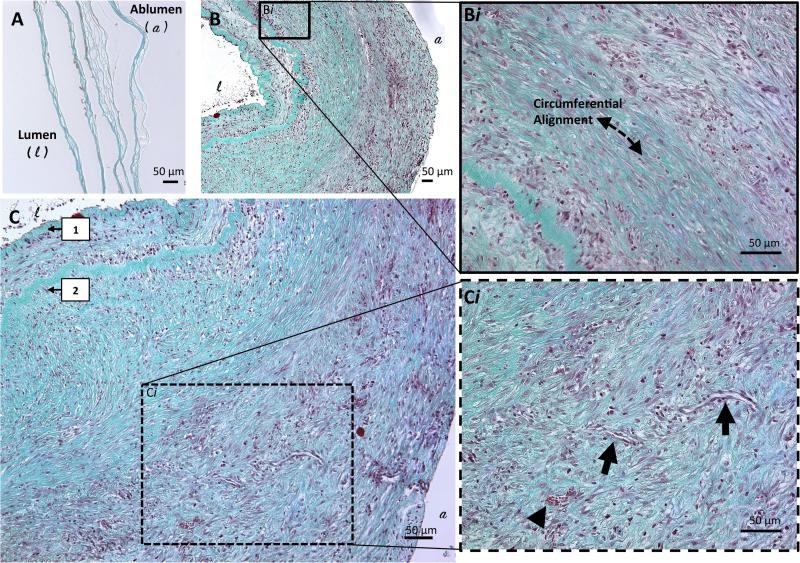

Significant graft remodeling was noted on histologic examination between one and four weeks post implantation (Figure 6A and B, respectively). This was evidenced by changes in observable mural cell density, connective tissue deposition, and overall increased consolidation of graft layers over time. The external (adventitial) layers of the construct were histologically notable for a homogenous pattern of organized connective tissue deposition, associated with an interspersed, uniform-appearing population of cells with mild to moderate density throughout the stroma. These cells and connective tissue pattern corresponded to construct layers demonstrating consolidation and coalescence. In contrast, the internal (lumenal) layers of the construct demonstrated a pattern of loose, disorganized connective tissue deposition associated with a high-density cell population. Cell distribution within the wall of the explant is easily visualized in Supplemental Figure 1A. Circumferentially aligned cellular populations, elongated in the direction of the dotted line in Figure 6Bi, appeared to morphologically approximate a vascular medial layer and displayed strong positive reactivity for α-actin (Supplemental Figure 1B). Figure 6C highlights the apparent remnants of the original six-layered hAM graft, reduced to only two discrete collagen-dense layers. Small capillaries were seen forming in the periphery of the vascular wall, as noted grossly in situ at the time of explant and on subsequent histological analysis (Figure 6Ci, arrows). Immunohistochemical study with CD31 demonstrated equivocal reactivity for endothelial elements along the construct lumen, but verified the establishment of peripheral microvasculature (Supplemental Figure 1B).

Figure 6. Histological evaluation of explanted grafts.

Histology of graft explants at one (A) and four weeks (B and C) stained with Masson's Trichrome. Cell population through the total thickness of the wall is seen in B, with circumferential alignment (as indicated by the dashed line in Bi) and newly deposited ECM demonstrating the extent of remodeling that occurs between weeks one and four. Progressive inward remodeling of the layered graft was seen and the remaining discernable layers of the original graft wall are indicated by the numbered arrows near the lumen (C). At higher power (Ci), the arrowhead highlights red blood cells and arrows point to longitudinal cross-sections through newly formed capillaries.

Inflammatory cell infiltrate was histologically identified. A patchy distribution of predominately mononuclear and plasmacytoid inflammatory cells were identified within the wall of the construct. Rather than a trans-mural distribution, the inflammatory cells were seen to preferentially infiltrate along the identifiable ECM layers near the lumen, as well as radially along the external adventitial-like zone. Isolated neutrophils and eosinophils were focal and rare.

DISCUSSION

The goal of these investigations was to conduct a preliminary feasibility assessment of utilizing a cell-less, human-derived scaffold in service of small-diameter vascular regeneration. This pilot study assessed, on both an in vitro and in vivo basis, three essential scaffold requirements for guided tissue regeneration: 1) maintenance of structural integrity, 2) lack of thrombosis or hyperacute rejection, and 3) promotion of cellular remodeling to suggest an attempt to approximate arterial vasculature.

The in vitro analyses focused primarily on the feasibility of cellular repopulation in a layered construct and the consequences of the repopulation on the grafts’ mechanical stability and biochemical changes under controlled conditions. Unlike the acellular scaffold that collapses post-rehydration without external physical support, cultured constructs displayed a qualitatively robust tubular conformation, with layers coalescing into a homogenous wall upon gross and histologic inspection. Statistically significant increases in GAG concentration and cell density suggest that the scaffold provides a hospitable environment for cellular integration and proliferation, potentially facilitating extensive ECM remodeling.

The coalescence of graft layers after four weeks in biomimetic culture correlated with increasing material stiffness and ultimate tensile strength. Biomechanical parameters were on the same order of magnitude as those described of healthy human coronary arteries, which served as the target vessel for graft replacement during in vitro investigation. Karimi et al. found that healthy human coronary arteries have elastic moduli of 1.55±0.26 MPa and ultimate tensile strengths of 1.44±0.87 MPa (as compared to the 1.29±0.59 MPa and 0.88±0.45 MPa, respectively, found in the present study).19 Physiological modulus of the cultured constructs, 0.06±0.03 MPa, was lower than that of published data for native human vessels, 1.48±0.24 MPa, and the acellular scaffolds, 0.120±0.0546 MPa, suggesting the construct is more compliant during early stages of remodeling when compared to the native vessel. This is consistent with increasing GAG concentration within the collagenous construct. However, vascular compliance is dynamic and known to be adaptive to the hemodynamic environment.20,21

The in vivo investigations served as a pilot proof-of principle for targeting specific anatomical locations, evaluating early scaffold remodeling, and testing dynamic fatigue.22 The acellular grafts endured the mechanical forces associated with surgical implantation and with the immediate exposure to the hemodynamic stress of systemic circulation. In this study, rabbits were immunocompetent and no post-surgical pharmacological treatment was administered. No hyperacute rejection of the biomaterial was noted clinically (as confirmed by the lack of vascular compromise on Doppler ultrasound following implantation), and all grafts remained patent over 28 days. No cerebrovascular compromise was noted. The histologic paucity of neutrophils and eosinophils suggests the absence of a nonspecific acute inflammatory response and allergic reaction, respectively. The absence of multinucleated foreign body giant cells formation was noted, suggesting the lack of a classic foreign-body response to the graft.

Histologic analysis showed organized remodeling of the hAM layers, with complete cellular integration of circumferentially-aligned, elongated, alpha-actin positive population of cells, interspersed amid newly-formed collagen. The pattern of connective tissue deposition from ablumen to lumen appears consistent with organized and still-active stromal remodeling, with appreciable capillary network formation in the graft periphery. It is interesting to note that the pattern of “early” connective tissue deposition near the lumen is associated with yet-discrete construct layers, suggesting a temporal heterogeneity to mural remodeling, with lumenal consolidation occurring as a late-stage event.

The described rolling methodology allows for a significant degree of patient-centered graft customization, effectively expanding the clinical applicability of this amnion-derived biomaterial. Fibrin adhesives can also be manufactured from a human origin, improving the feasibility of clinical translation.23,24 Diameter, length, wall thickness and shape can be easily adjusted to generate custom vascular grafts for routine or complex vascular reconstruction in a variety of anatomical sites and patient populations. This could include arteriovenous grafts to allow hemodialysis access for patients suffering from end stage renal disease, coronary artery bypass grafts to prevent or palliate ischemic heart disease, and personalized grafts for modified Fontan's procedures to treat complex congenital heart disease in pediatric populations.

Important areas for future work include detailed evaluation of graft functional remodeling capacity (e.g., via phenotypic assessment of both stromal and inflammatory cellular elements), as well as study of graft longevity in vivo. These preliminary investigations focused on early remodeling to characterize the initial thrombogenicity and cellular integration whereas longer in vivo analysis would be necessary to determine the resolution of these early remodeling events. Longer implantation times would additionally help to elucidate the biological significance of the trending increase in wall thickness, potentially differentiating between progressive graft stenosis versus transient phenomena of early remodeling.

CONCLUSIONS

This approach has multiple advantages: the material is derived from abundantly available human ECM and it can be readily prepared into an acellular graft of a wide range of geometries. With endogenous biological components, the ECM is readily degradable and, in theory, should allow for in situ growth. This growth potential makes the scaffold particularly appealing for use in various applications, from treatment of adult coronary artery disease to vascular reconstruction of complex congenital heart disease in pediatric patients. As a preliminary investigation, these works have demonstrated that grafts possess adequate mechanical integrity, postoperative immunologic tolerance lasting at least four weeks, and evidence of cellular remodeling approximating the native vascular architecture. Further investigation that details cellular behavior, inflammatory infiltration and graft longevity will aid in our understanding of in situ graft remodeling. As human tissue in a rabbit model, the human amnion-derived ECM scaffold showed signs of constructive remodeling and, with further investigation, holds promise as a platform for allogeneic vascular tissue reconstruction.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Relevance.

This preliminary study introduces the use of an allogeneic, cell-free, small-diameter vascular graft derived from the rolled human amniotic membrane. With this approach, graft diameter and wall thickness can be modulated to create conduits of specified dimensions. The ultimate goal is for the graft to integrate with native vasculature, allowing for subsequent growth potential. Future work is needed to evaluate long-term remodeling and viability; however, in vivo investigation provides evidence that the layered scaffold can both mechanically withstand the stress of surgical implantation into native vasculature, and subsequently support infiltration and early remodeling by host cell populations over four-weeks.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Angela Cuenca and Qiongyao Hu for their generous help and contributions to the animal study. We would like to thank Marda Jorgensen for lending her expertise in histology. Furthermore, we would like to acknowledge the Labor and Deliver Department at UF Health Shands hospital system (Gainesville, FL) for providing access to the placentas used in this study [University of Florida Institutional Review Board approval #64-2010]. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [R01-HL088207].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Murphy S, Xu J, Kochanek K. Deaths: Final Data for 2010. National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harskamp RE, Williams JB, Hill RC, de Winter RJ, Alexander JH, Lopes RD. Saphenous vein graft failure and clinical outcomes: toward a surrogate end point in patients following coronary artery bypass surgery? Am Heart J. 2013;165(5):639–643. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taggart DP. Current status of arterial grafts for coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;2(4):427–430. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.07.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.L'Heureux N, Paquet S, Labbe R, Germain L, Auger FA. A completely biological tissue-engineered human blood vessel. FASEB J. 1998;12(1):47–56. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wystrychowski W, McAllister TN, Zagalski K, Dusserre N, Cierpka L, L'Heureux N. First human use of an allogeneic tissue-engineered vascular graft for hemodialysis access. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(5):1353–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amensag S, McFetridge PS. Tuning scaffold mechanics by laminating native extracellular matrix membranes and effects on early cellular remodeling. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102(5):1325–1333. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adinolfi M, Akle CA, McColl I, Fensom AH, Tansley L, Connolly P, et al. Expression of HLA antigens, beta 2-microglobulin and enzymes by human amniotic epithelial cells. Nature. 1982;295(5847):325–327. doi: 10.1038/295325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akle CA, Adinolfi M, Welsh KI, Leibowitz S, McColl I. Immunogenicity of human amniotic epithelial cells after transplantation into volunteers. Lancet. 1981;2(8254):1003–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)91212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammer A, Hutter H, Blaschitz A, Mahnert W, Hartmann M, Uchanska-Ziegler B, et al. Amnion epithelial cells, in contrast to trophoblast cells, express all classical HLA class I molecules together with HLA-G. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1997;37(2):161–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen CL, Clare G, Stewart EA, Branch MJ, McIntosh OD, Dadhwal M, et al. Augmented Dried versus Cryopreserved Amniotic Membrane as an Ocular Surface Dressing. PLoS One. 2013;8(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkinson A, McIntosh RS, Tighe PJ, James DK, Dua HS. Amniotic membrane for ocular surface reconstruction: donor variations and the effect of handling on TGF-beta content. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(10):4316–4322. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walgenbach KJ, Bannasch H, Kalthoff S, Klinik R, Rubin JP. Randomized, Prospective Study of TissuGlu® Surgical Adhesive in the Management of Wound Drainage Following Abdominoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;36(3):491–496. doi: 10.1007/s00266-011-9844-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mamede AC, Carvalho MJ, Abrantes M, Laranjo M, Maia CJ, Botelho MF. Amniotic membrane: from structure and functions to clinical applications. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;349(2):447–458. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amensag S, McFetridge PS. Rolling the Human Amnion to Engineer Laminated Vascular Tissues. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2012;18(11):903–12. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilshaw SP, Kearney JN, Fisher J, Ingham E. Production of an acellular amniotic membrane matrix for use in tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(8):2117–2129. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoemann CD, Sun J, Chrzanowski V, Buschmann MD. A multivalent assay to detect glycosaminoglycan, protein, collagen, RNA, and DNA content in milligram samples of cartilage or hydrogel-based repair cartilage. Anal Biochem. 2002;300(1):1–10. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farndale RW, Buttle DJ, Barrett AJ. Improved quantitation and discrimination of sulphated glycosaminoglycans by use of dimethylmethylene blue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;883(2):173–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang Z, Wu L, Miller BL, Goldman DR, Fernandez CM, Abouhamze ZS, et al. A novel vein graft model: adaptation to differential flow environments. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286(1):H240–245. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00760.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karimi A, Navidbakhsh M, Shojaei A, Faghihi S. Measurement of the uniaxial mechanical properties of healthy and atherosclerotic human coronary arteries. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2013;33(5):2550–2554. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haga JH, Li YS, Chien S. Molecular basis of the effects of mechanical stretch on vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biomech. 2007;40(5):947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nerem RM. Role of mechanics in vascular tissue engineering. Biorheology. 2003;40(1-3):281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.L'Heureux N, Dusserre N, Marini A, Garrido S, de la Fuente L, McAllister T. Technology insight: the evolution of tissue-engineered vascular grafts--from research to clinical practice. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4(7):389–395. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dietrich M, Heselhaus J, Wozniak J, Weinandy S, Mela P, Tschoeke B, et al. Fibrin-based tissue engineering: comparison of different methods of autologous fibrinogen isolation. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2013;19(3):216–226. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2011.0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirouzian A, Ly H, Holz H, Sudesh RS, Chuck RS. Fibrin-glue assisted multilayered amniotic membrane transplantation in surgical management of pediatric corneal limbal dermoid: a novel approach. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249(2):261–265. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1499-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.