Abstract

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has long been used for patients with psoriasis. This study aimed to investigate TCM usage in patients with psoriasis. We analyzed a cohort of one million individuals representing the 23 million enrollees randomly selected from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan. We identified 28,510 patients newly diagnosed with psoriasis between 2000 and 2010. Among them, 20,084 (70.4%) patients were TCM users. Patients who were female, younger, white-collar workers and lived in urbanized area tended to be TCM users. The median interval between the initial diagnosis of psoriasis to the first TCM consultation was 12 months. More than half (N = 11,609; 57.8%) of the TCM users received only Chinese herbal medicine. Win-qing-yin and Bai-xian-pi were the most commonly prescribed Chinese herbal formula and single herb, respectively. The core prescription pattern comprised Mu-dan-pi, Wen-qing-yin, Zi-cao, Bai-xian-pi, and Di-fu-zi. Patients preferred TCM than Western medicine consultations when they had metabolic syndrome, hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, alopecia areata, Crohn's disease, cancer, depression, fatty liver, chronic airway obstruction, sleep disorder, and allergic rhinitis. In conclusion, TCM use is popular among patients with psoriasis in Taiwan. Future clinical trials to investigate its efficacy are warranted.

1. Introduction

Psoriasis is a common chronic immune-mediated inflammation disease. The prevalence rates of psoriasis ranged from 0.7% to 2.9% in Europe, 0.7 to 2.6% in the United States [1], and 0.235% in Taiwan [2]. The burden of psoriasis was estimated as $35.2 billion in 2013 in the United States [3], while the estimated annual total cost for psoriasis was $53.8 million in Taiwan [4]. The cost of long-term therapy and social economic burden of psoriasis have posed a significant impact on healthcare system.

Current treatment for psoriasis is not fully satisfactory. Several types of dermatological treatment are available, ranging from corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, and phototherapy for mild-moderate psoriasis to retinoids, methotrexate, cyclosporine, apremilast, and biologic immune modifying agents for severe psoriasis [5]. However, many patients are concerned about the side effects of these treatments. Skin atrophy may be induced by long-term use of topical corticosteroids [6]. Common adverse events of topical steroid and vitamin D agent may be partial local irritation and skin pain [7]. Apremilast may cause nausea, upper respiratory tract infection, and diarrhea [8]. Phototherapy may increase the risk of skin cancer [9]. Methotrexate was associated with the increased risk of liver injury [10]. Oral cyclosporin may have the risk of kidney toxicity [11]. A web-based survey study showed that patients with psoriasis were moderately satisfied with their treatment [12].

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which includes acupuncture and moxibustion, Chinese traumatology, and Chinese herbal medicine (CHM), has been integrated as an important part of healthcare in Taiwan. It has been commonly used for dermatitis [13], gastrointestinal disease [14], rheumatoid arthritis [15], diabetic mellitus [16, 17], gynecological disorder [18], and cancer [19, 20] patients. Previous studies showed that CHM plus acitrerin had add-on effect [21] and Chinese herbal bath combined with phototherapy was superior to phototherapy alone [22] for psoriasis. Topical application of Lindioil, extract of Qing-dai (Indigo Naturalis; Baphicacanthus cusia (Nees) Bremek, Polygonum tinctorium Aiton, Isatis indigotica Fortune ex Lindl.) in oil, was effective for treating nail psoriasis [23] and Chinese herbal ointment that contains Qing-dai was effective for plaque-type psoriasis [24].

In the United States, 2.0% of patients with psoriasis received complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapy [25]. Despite the growing interests in utilizing CAM, there remains a critical knowledge gap on the ethnopharmacological analysis of the TCM prescription patterns for psoriasis patients.

In Taiwan, the compulsory National Health Insurance (NHI) system was launched in 1995 and the NHI program started to reimburse TCM service in 1996. As of 2015, The NHI program covered 99.6% of Taiwanese population [26]. To investigate the prescription patterns of CHM for psoriasis patients, we took advantage of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which contains registration files and claims data for reimbursement. We analyzed a cohort of one million beneficiaries from the NHIRD from 2000 to 2010. This study is important to delineate the TCM utilization patterns among patients with psoriasis. It could be regarded as a consensus of TCM formulas/herbs for further pharmacological investigation or clinical trials.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Data Source

This study used datasets from the NHIRD (http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/) in Taiwan as our previous reports [14, 18]. The NHI program in Taiwan reimbursed TCM services (CHM, acupuncture/moxibustion, and Chinese traumatology therapy) provided by licensed TCM doctors. The NHI database consists of registration files and original claim data for reimbursement. The large-scale computerized data derived from the NHI program were maintained by the National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan, and provided to scientists in Taiwan for research purposes. All registration data in the NHIRD consist of demographic characteristics, diagnosis, clinical visits, hospitalization, procedures, prescriptions, and the medical costs for reimbursement [27]. The diagnostic codes were in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) formats.

2.2. Study Population and Variables

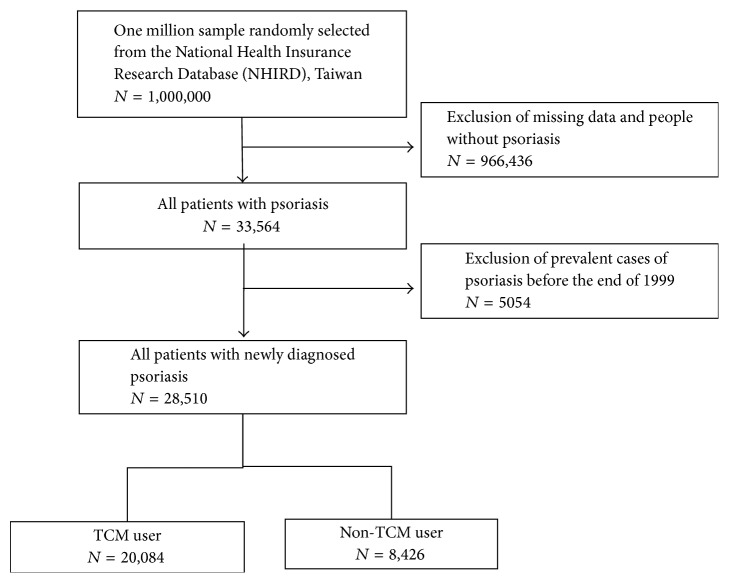

The flow chart of enrolling psoriasis patients was shown in Figure 1. A one million random sample from the NHIRD was selected for this study. All the patients (n = 28,510) with newly diagnosed psoriasis (ICD-9-CM code: 696) between January 2000 and December 2010 were included in this study and then followed up until the end of 2011. After a confirmed diagnosis with psoriasis, those consulted with TCM doctors were grouped as TCM users (n = 20,084) and the others as non-TCM users (n = 8426). We investigated the demographic characteristics of TCM users and non-TCM users, including sex, age, occupation, urbanization, and the time between being diagnosed of psoriasis and TCM treatment. We analyzed the incidence rate ratio of diseases between TCM and non-TCM users. We also analyzed ten most common herbal formulas and single herbs prescribed by TCM doctors for psoriasis patients. Herbal formulas were listed in pin-yin name and English name. Single herbs were listed in pin-yin name, Latin name, and botanical plant name. TCM indications of the Chinese herbal formulas and single herbs were based on TCM theory [28, 29]. Full botanical names comply with the International Plant Names List (IPNI; http://www.ipni.org/) and The Plant List (http://www.theplantlist.org/) [30].

Figure 1.

Flow recruitment chart of subjects from the one million random samples obtained from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) from 2000 to 2010 in Taiwan.

2.3. Core Patterns of Chinese Herbal Medicine

The core pattern of CHM used in treating psoriasis patients was identified with an open-sourced freeware NodeXL (http://nodexl.codeplex.com/), and all the selected two drugs combinations were applied in this network analysis. The line width, ranging from 1 to 5 in the network figure, was defined by counts of connections between a CHM and coprescribed CHM, and thicker widths of line connections indicated a significant prescription pattern [31]. The network analysis manifested the core pattern of the top 50 two-drug combinations in this survey.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

All of the information that could be used to identify individuals or care providers were deidentified and encrypted before release. It is not possible to identify any individuals or care providers at any level in this database. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital (CMUH104-REC2-115).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We used the SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), to analyze the datasets retrieved from the NHIRD. Descriptive statistics was applied to determine the demographic characteristics, treatment modalities, and the frequency of prescribed herbal formulas and single herbs. The diagnoses were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. To present the overall structure of the study groups, we showed the mean and standard deviation (SD) for age and number and percentage for sex and comorbidity. To assess the distribution difference between TCM and non-TCM users, the t-test was used for continuous variable (age) and chi-square test was used for category variables (sex, occupation, urbanization, and major disease categories/diagnosis). The crude and adjusted prevalence rate ratio (PRR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of those particular diseases for the TCM users compared with non-TCM users were estimated using Poisson regression models. A p value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

There were 28,510 patients who were newly diagnosed with psoriasis (Table 1). Among them, 20,084 (70.4%) patients ever used TCM outpatient services. The majority (54.9%) of the TCM users were female. The mean age of TCM users was younger than that of non-TCM users (30.0 versus 34.5 years old). The majority (59.2%) of the TCM users were white-collar workers. Most of the TCM users resided in urbanized areas. The average time between onset of psoriasis and the first visit to a TCM clinic was 12.0 months.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of TCM and non-TCM users among patients with psoriasis from 2000 to 2010 in Taiwan.

| Variable | Non-TCM users | TCM users | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Number of cases | 8426 | 29.6 | 20084 | 70.4 | |

| Sex† | <0.0001 | ||||

| Female | 3457 | 41.0 | 11035 | 54.9 | |

| Male | 4969 | 59.0 | 9049 | 45.1 | |

| Age†, y | <0.0001 | ||||

| <25 | 3560 | 42.3 | 9601 | 47.8 | |

| 25–35 | 1275 | 15.1 | 3681 | 18.3 | |

| 35–65 | 2451 | 29.1 | 5554 | 27.7 | |

| ≧65 | 1140 | 13.5 | 1248 | 6.2 | |

| Mean (SD)# | 34.5 (22.7) | 30.0 (18.7) | <0.0001 | ||

| Occupation† | <0.0001 | ||||

| White collar$ | 4716 | 56.0 | 11892 | 59.2 | |

| Blue collar※ | 2475 | 29.4 | 5805 | 28.9 | |

| Others‡ | 1235 | 14.7 | 2387 | 11.9 | |

| Urbanization† | 0.0090 | ||||

| 1 (highest) | 2487 | 29.5 | 5992 | 29.8 | |

| 2 | 2467 | 29.3 | 6007 | 29.9 | |

| 3 | 1514 | 18.0 | 3773 | 18.8 | |

| 4+ (lowest) | 1958 | 23.2 | 4312 | 21.5 | |

| Interval between the diagnosis of psoriasis and the first visit to a TCM clinic, months, median (IQR) | 12.0 (28.4) | ||||

†Chi-square test; #Student's t-test.

$White collar: civil services, institution workers, enterprise, business, and industrial administration personnel. ※Blue collar: farmers, fishermen, vendors, and industrial laborers. ‡Others: retired, unemployed and low-income populations.

Regarding the treatment modalities given to patients with psoriasis, 11,609 (57.8%) patients received only CHM, while 214 (1.1%) patients were treated by acupuncture or Chinese traumatology only and 8,261 (41.1%) patients received the combination of both treatments. More than half of the patients (n = 11,037; 55.0%) visited TCM clinics for more than 6 times per year (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of TCM clinic visits and treatment modalities among TCM users from 2000 to 2010 in Taiwan.

| Number of TCM visits | Only Chinese herbal medicine N = 11609 (57.8%) |

Only Acupuncture or traumatology N = 214 (1.1%) |

Combination of both treatments N = 8261 (41.1%) |

Total N = 20084 (100%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | 4753 (40.9) | 201 (93.9) | 924 (11.2) | 5878 (29.3) |

| 4–6 | 1903 (16.4) | 10 (4.7) | 1256 (15.2) | 3169 (15.7) |

| >6 | 4953 (42.7) | 3 (1.4) | 6081 (73.6) | 11037 (55.0) |

To investigate the prescription patterns of the Chinese herbal remedies, we conducted a comprehensive analysis and identified ten most commonly prescribed Chinese herbal formulas (Table 3) and single herbs (Table 4), respectively. The most frequently prescribed Chinese herbal formula was Win-qing-yin (Warm Clearing Beverage). Regarding the single herbs for the treatment of psoriasis, Bai-xian-pi (Cortex Dictamni; Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz.) was the most commonly prescribed single herb.

Table 3.

Ten most common herbal formulas prescribed for the treatment of patients with psoriasis from 2000 to 2010 in Taiwan.

| Herbal formula | Ingredients of herbal formula | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pin-yin name | English name | Pin-yin name (Chinese material medica name; botanical name) | Therapeutic actions and indications based on TCM theory | Number | Average daily dose (g) |

| Wen-qing-yin | Warm Clearing Beverage | Dang-gui (Radix Angelicae Sinensis; Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels), Chuan-xiong (Rhizoma Chuanxiong; Ligusticum chuanxiong S.H.Qiu, Y.Q.Zeng, K.Y.Pan, Y.C.Tang & J.M.Xu), Bai-shao-yao (Radix Paeoniae Alba; Paeonia lactiflora Pall.), Shou-di-huang (Radix Rehmanniae Preparate; Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC.), Huang-qin (Radix Scutellariae; Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi), Huang-bai (Cortex Phellodendri; Phellodendron amurense Rupr.), Zhi-zi (Fructus Gardeniae; Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis), Huang-lian (Rhizoma Coptidis; Coptis chinensis Franch.; Coptis deltoidea C.Y.Cheng & P.K.Hsiao; Coptis teeta Wall.) | Clear heat, transform dampness, and nourish the blood | 1450 | 33.5 |

|

| |||||

| Xiao-feng-san | Wind-Dispersing Powder | Jing-jie (Herba Schizonepetae; Schizonepeta tenuifolia (Benth.) Briq.), Fang-feng (Radix Saposhnikoviae; Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk.), Chan-tui (Periostracum Cicadae; Cryptotympana pustulata Fabricius), Ren-shen (Radix Ginseng; Panax ginseng C.A.Mey.), Gan-cao (Radix Glycyrrhizae; Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.; Glycyrrhiza inflata Batalin; Glycyrrhiza glabra L.), Chuan-xiong (Rhizoma Chuanxiong; Ligusticum chuanxiong S.H.Qiu, Y.Q.Zeng, K.Y.Pan, Y.C.Tang & J.M.Xu), Qiang-huo (Rhizoma et Radix Notopterygii; Notopterygium incisum K.C.Ting ex H.T.Chang), Jiang-can (Batryticatus Bombyx; Bombyx mori Linnaeus), Hou-po (Cortex Magnoliae Officinalis; Magnolia officinalis Rehder & E.H.Wilson; Magnolia officinalis var. biloba Rehder & E.H.Wilson), Huo-xiang (Herba Pogostemonis; Agastache rugosa (Fisch. & C.A.Mey.) Kuntze), Fu-ling (Poria; Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf), Chen-pi (Pericarpium Citri Reticulate; Citrus reticulata Blanco) | Course wind and discharge heat | 763 | 25.5 |

|

| |||||

| Long-dan-xie-gan-tang | Gentian Liver-Draining Decoction | Long-dan-cao (Radix Gentianae; Gentiana scabra Bunge; Gentiana triflora Pall.; Gentiana manshurica Kitag.), Zhi-zi (Fructus Gardeniae; Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis), Huang-qin (Radix Scutellariae; Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi), Chai-hu (Radix Bupleuri; Bupleurum chinense DC.), Sheng-di-huang (Radix Rehmanniae; Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC.), Ze-xie (Rhizoma Alismatis; Alisma plantago-aquatica L.), Dang-gui (Radix Angelicae Sinensis; Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels), Che-qian-zi (Semen Plantaginis; Plantago asiatica L.; Plantago depressa Willd.), Chuan-mu-tong (Caulis Clematidis Armandii; Clematis armandii Franch.), Gan-cao (Radix Glycyrrhizae; Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.; Glycyrrhiza inflata Batalin; Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) | Drain liver fire and clear damp heat | 517 | 9.99 |

|

| |||||

| Jia-wei-xiao-yao-san | Supplemented Free Wanderer Powder | Dang-gui (Radix Angelicae Sinensis; Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels), Fu-ling (Poria; Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf), Zhi-zi (Fructus Gardeniae; Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis), Bo-he (Herba Menthae; Mentha haplocalyx Briq.), Bai-shao-yao (Radix Paeoniae Alba; Paeonia lactiflora Pall.), Chai-hu (Radix Bupleuri; Bupleurum chinense DC.), Gan-cao (Radix Glycyrrhizae; Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.; Glycyrrhiza inflata Batalin; Glycyrrhiza glabra L.), Bai-zhu (Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae; Atractylis macrocephala (Koidz.) Hand.-Mazz.), Mu-dan-pi (Cortex Moutan; Paeonia suffruticosa Andrews), Wei-jiang (Rhizoma Praeparatum Zingiberis; Zingiber officinale Roscoe) | Rectify Qi and nourish blood | 461 | 20.0 |

|

| |||||

| Dang-gui-yin-zi | Chinese Angelica Drink | Dang-gui (Radix Angelicae Sinensis; Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels), Chuan-xiong (Rhizoma Chuanxiong; Ligusticum chuanxiong S.H.Qiu, Y.Q.Zeng, K.Y.Pan, Y.C.Tang & J.M.Xu), Bai-shao-yao (Radix Paeoniae Alba; Paeonia lactiflora Pall.), Sheng-di-huang (Radix Rehmanniae; Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC.), Bai-ji-li (Fructus Tribulus; Tribulus terrestris L.), Fang-feng (Radix Saposhnikoviae; Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk.), Jing-jie (Herba Schizonepetae; Schizonepeta tenuifolia (Benth.) Briq.), He-shou-wu (Radix Polygoni Multiflori; Polygonum multiflorum Thunb.), Huang-qi (Radix Astragali; Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge), Gan-cao (Radix Glycyrrhizae; Glycyrrhiza inflata Batalin; Glycyrrhiza glabra L.), Sheng-jiang (Rhizoma Zingiberis Recens; Zingiber officinale Roscoe) | Nourish the blood, moisten dryness, dispel wind, and relieve itching | 435 | 65.4 |

|

| |||||

| Xue-fu-zhu-yu-tang | House of Blood Stasis-Expelling Decoction | Dang-gui (Radix Angelicae Sinensis; Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels), Sheng-di-huang (Radix Rehmanniae; Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC.), Tao-ren (Semen Persicae; Prunus persica (L.) Batsch; Prunus davidiana (CarriŠre) Franch.), Hong-hua (Flos Carthami; Carthamus tinctorius L.), Zhi-ke (Fructus Aurantii; Citrus aurantium L.), Chi-shao-yao (Radix Rubra Paeoniae; Paeonia lactiflora Pall.), Chai-hu (Radix Bupleuri; Bupleurum chinense DC.), Gan-cao (Radix Glycyrrhizae; Glycyrrhiza inflata Batalin; Glycyrrhiza glabra L.), Jie-geng (Radix Platycodonis; Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC.), Chuan-xiong (Rhizoma Chuanxiong; Ligusticum chuanxiong S.H.Qiu, Y.Q.Zeng, K.Y.Pan, Y.C.Tang & J.M.Xu), Niu-xi (Radix Cyathulae; Achyranthes bidentata Blume; Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan) | Quicken the blood, transform stasis, move qi, and relieve pain | 430 | 2.97 |

|

| |||||

| Zhi-bai-di-huang-wan | Anemarrhena, Phellodendron, and Rehmannia Pill | Shou-di-huang (Radix Rehmanniae Praeparate; Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC.); Shan-zhu-yu (Fructus Corni; Cornus officinalis Siebold & Zucc.), Shan-yao (Rhizoma Dioscoreae; Dioscorea opposita Thunb.), Fu-ling (Poria; Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf), Mu-dan-pi (Cortex Moutan; Paeonia suffruticosa Andrews), Ze-xie (Rhizoma Alismatis; Alisma plantago-aquatica L.), Zhi-mu (Rhizoma Anemarrhenae; Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge), Huang-bai (Cortex Phellodendri; Phellodendron amurense Rupr.) | Enrich yin and downbear fire | 414 | 7.85 |

|

| |||||

| Huang-lian-jie-du-tang | Coptis Toxin-Resolving Decoction | Huang-qin (Radix Scutellariae; Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi), Huang-bai (Cortex Phellodendri; Phellodendron amurense Rupr.), Zhi-zi (Fructus Gardeniae; Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis), Huang-lian (Rhizoma Coptidis; Coptis chinensis Franch.; Coptis deltoidea C.Y.Cheng & P.K.Hsiao; Coptis teeta Wall.) | Drain fire and resolve toxin | 347 | 8.95 |

|

| |||||

| Xiang-sha-liu-jun-zi-tang | Costusroot and Amomum Six Gentlemen Decoction | Mu-xiang (Radix Aucklandiae; Aucklandia lappa DC.; Vladimiria souliei (Franch.) Ling), Sha-ren (Fructus Amomi; Amomum villosum Lour.; Amomum longiligulare T.L.Wu; Amomum xanthioides Wall. ex Baker), Chen-pi (Pericarpium Citri Reticulate; Citrus reticulata Blanco), Ban-xia (Rhizoma Pinelliae; Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino), Ren-shen (Radix Ginseng; Panax ginseng C.A.Mey.), Bai-zhu (Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae; Atractylis macrocephala (Koidz.) Hand.-Mazz.), Fu-ling (Poria; Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf), Gan-cao (Radix Glycyrrhizae; Glycyrrhiza inflata Batalin; Glycyrrhiza glabra L.), Sheng-jiang (Rhizoma Zingiberis Recens; Zingiber officinale Roscoe), Da-zao (Fructus Jujubae; Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) | Boost qi, fortify spleen, move qi, and reduce phlegm | 284 | 5.32 |

|

| |||||

| Jing-fang-bai-du-san | Schizonepeta and Saposhnikovia Toxin-Vanquishing Powder | Jing-jie (Herba Schizonepetae; Schizonepeta tenuifolia (Benth.) Briq.), Fang-feng (Radix Saposhnikoviae; Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk.), Chai-hu (Radix Bupleuri; Bupleurum chinense DC.), Fu-ling (Poria; Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf), Jie-geng (Radix Platycodonis; Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC.), Chuan-xiong (Rhizoma Chuanxiong; Ligusticum chuanxiong S.H.Qiu, Y.Q.Zeng, K.Y.Pan, Y.C.Tang & J.M.Xu), Du-huo (Radix Angelicae Pubescentis; Angelica pubescens Maxim.), Zhi-ke (Fructus Aurantii; Citrus aurantium L.), Gan-cao (Radix Glycyrrhizae; Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.; Glycyrrhiza inflata Batalin; Glycyrrhiza glabra L.), Sheng-jiang (Rhizoma Zingiberis Recens; Zingiber officinale Roscoe) | Promote sweating, resolve the exterior, disperse wind, and dispel dampness | 211 | 10.5 |

Table 4.

Top ten most common single herbs prescribed for the treatment of patients with psoriasis from 2000 to 2010 in Taiwan.

| Single herb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pin-yin name | Chinese materia medica name | Botanical name | Therapeutic actions and indications based on TCM theory | Number | Average daily dose (g) |

| Bai-xian-pi | Cortex Dictamni | Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz. | Clearing heat, drying dampness, dispelling wind, and resolving toxin | 783 | 1.52 |

| Mu-dan-pi | Cortex Moutan | Paeonia suffruticosa Andrews | Clearing heat, cooling the blood, quickening the blood, and dispersing stasis | 721 | 3.88 |

| Sheng-di-huang | Radix Rehmanniae | Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. | Clearing heat, cooling the blood, nourishing yin, and engendering liquid | 602 | 5.98 |

| Tu-fu-ling | Rhizoma Smilacis Glabrae | Smilax glabra Roxb. | Resolving toxin and drying dampness | 502 | 7.28 |

| Dan-shen | Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae | Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge | Clearing and quickening the blood and regulating menstruation | 479 | 1.30 |

| Zi-cao | Radix Lithospermi | Lithospermum erythrorhizon Siebold & Zucc.; Arnebia euchroma (Royle) I.M.Johnst.; Arnebia guttata Bunge | Clearing and quickening the blood, resolving toxin, and outthrusting papules | 469 | 1.38 |

| Di-fu-zi | Fructus Kochiae | Kochia scoparia (L.) Schrad. | Clearing heat, drying dampness, and relieving itching | 440 | 8.44 |

| Lian-qiao | Fructus Forsythiae | Forsythia suspensa (Thunb.) Vahl | Clearing heat, resolving toxin, coursing wind, and dispersing heat | 440 | 23.5 |

| Chi-shao-yao | Radix Rubra Paeoniae | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. | Clearing heat, cooling the blood, dispersing stasis, and relieving pain | 402 | 1.31 |

| Jin-yin-hua | Flos Lonicerae | Lonicera japonica Thunb. | Clearing heat, resolving toxin, coursing wind, and dispersing heat | 392 | 16.8 |

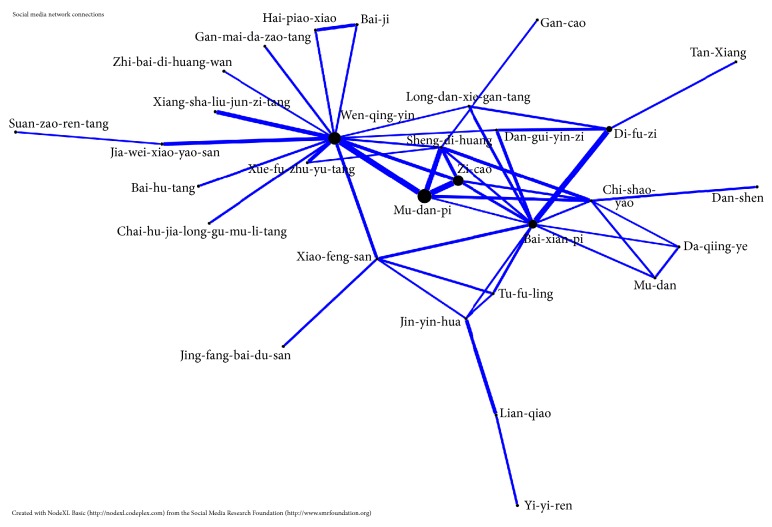

To further investigate the core prescription patterns, we conducted the network analysis. We found that Mu-dan-pi (Cortex Moutan; Paeonia suffruticosa Andrews), Win-qing-yin (Warm Clearing Beverage), Zi-cao (Radix Lithospermi; Lithospermum erythrorhizon Siebold & Zucc.; Arnebia euchroma (Royle) I.M.Johnst.; Arnebia guttata Bunge), Bai-xian-pi (Cortex Dictamni; Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz.), and Di-fu-zi (Fructus Kochiae; Kochia scoparia (L.) Schrad.) composed the core prescription patterns of CHM to treat psoriasis patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The top 50 combinations of herbal formulas and single herbs for psoriasis patients were analyzed through open-sourced freeware NodeXL. The core prescription pattern was Mu-dan-pi, Wen-qing-yin, Zi-cao, Bai-xian-pi, and Di-fu-zi.

Comparing the disease prevalence rate ratio of TCM and non-TCM group, we found that psoriasis patients with certain disease tended to consult TCM service more than Western medicine consultation (Table 5). Specifically, psoriasis patients preferred to visit TCM doctors when they had metabolic syndrome, hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, alopecia areata, Crohn's disease, cancer, depression, fatty liver, chronic airway obstruction, sleep disorder, and allergic rhinitis.

Table 5.

Prevalence rate ratio of diseases between non-TCM and TCM users.

| Non-TCM N = 8426 |

TCM N = 20084 |

Compared to non-TCM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Crude PRR | Adjusted PRR† | |

| Metabolic syndrome | ||||||

| Hypertension | 1817 | 21.6 | 3173 | 15.8 | 0.73 (0.70–0.77)∗∗∗ | 1.18 (1.11–1.26)∗∗∗ |

| Diabetes | 1000 | 11.9 | 1727 | 8.6 | 0.72 (0.69–0.76)∗∗∗ | 1.14 (1.05–1.24)∗∗ |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1221 | 14.5 | 2666 | 13.3 | 0.92 (0.87–0.96)∗∗∗ | 1.29 (1.20–1.39)∗∗∗ |

| Heart disease | 1379 | 16.4 | 2707 | 13.5 | 0.82 (0.78–0.86)∗∗∗ | 1.20 (1.11–1.28)∗∗∗ |

| Infections | ||||||

| Tuberculosis | 153 | 1.82 | 198 | 0.99 | 0.54 (0.51–0.58)∗∗∗ | 0.94 (0.74–1.19) |

| Hepatitis B | 376 | 4.46 | 1193 | 5.94 | 1.33 (1.25–1.42)∗∗∗ | 1.46 (1.29–1.65)∗∗∗ |

| Hepatitis C | 184 | 2.18 | 435 | 2.17 | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | 1.39 (1.16–1.68)∗∗∗ |

| Auto immune disorder | ||||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 15 | 0.18 | 48 | 0.24 | 1.34 (1.22–1.48)∗∗∗ | 1.93 (1.03–3.60)∗ |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 16 | 0.19 | 25 | 0.12 | 0.66 (0.60–0.71)∗∗∗ | 0.59 (0.29–1.17) |

| Vitiligo | 40 | 0.47 | 123 | 0.61 | 1.29 (1.18–1.41)∗∗∗ | 1.11 (0.77–1.62) |

| Pemphigoid | 16 | 0.19 | 16 | 0.08 | 0.42 (0.39–0.46)∗∗∗ | 0.86 (0.39–1.89) |

| Pemphigus | 15 | 0.18 | 14 | 0.07 | 0.39 (0.36–0.43)∗∗∗ | 0.58 (0.26–1.32) |

| Alopecia areata | 88 | 1.04 | 297 | 1.48 | 1.42 (1.31–1.54)∗∗∗ | 1.36 (1.06–1.75)∗ |

| Crohn's disease | 449 | 5.33 | 1610 | 8.02 | 1.50 (1.41–1.60)∗∗∗ | 1.32 (1.18–1.47)∗∗∗ |

| Cancer | 329 | 3.90 | 597 | 2.97 | 0.76 (0.71–0.81)∗∗∗ | 1.24 (1.07–1.44)∗∗ |

| Others | ||||||

| Depression | 379 | 4.50 | 1200 | 5.97 | 1.33 (1.24–1.42)∗∗∗ | 1.41 (1.25–1.60)∗∗∗ |

| Hyperthyroidism | 157 | 1.86 | 400 | 1.99 | 1.07 (0.99–1.15) | 0.99 (0.81–1.21) |

| Hypothyroidism | 49 | 0.58 | 153 | 0.76 | 1.31 (1.20–1.43)∗∗∗ | 1.20 (0.85–1.70) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 5 | 0.06 | 15 | 0.07 | 1.26 (1.14–1.39)∗∗∗ | 1.02 (0.35–2.99) |

| Fatty liver | 144 | 1.71 | 331 | 1.65 | 0.96 (0.90–1.04) | 1.30 (1.05–1.61)∗∗ |

| Chronic airways obstruction | 348 | 4.13 | 452 | 2.25 | 0.54 (0.51–0.58)∗∗∗ | 1.19 (1.02–1.39)∗ |

| Sleep disorder | 1046 | 12.4 | 4407 | 21.9 | 1.77 (1.68–1.86)∗∗∗ | 1.77 (1.65–1.90)∗∗∗ |

| Asthma | 1008 | 12.0 | 2303 | 11.5 | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1956 | 23.2 | 6687 | 33.3 | 1.43 (1.37–1.50)∗∗∗ | 1.26 (1.20–1.33)∗∗∗ |

PRR: prevalence rate ratio. †Model adjusted for age, sex, occupation, urbanization, and number of outpatient visits for traditional Chinese medicine. ∗ p ≤ 0.05; ∗∗ p ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗ p ≤ 0.001.

4. Discussion

This nationwide population-based study analyzed a cohort of one million beneficiaries from the NHIRD to investigate the TCM usage among patients with psoriasis. We found that approximately 70.4% of the patients with psoriasis visited TCM clinics. Psoriasis patients with female gender, a younger age, residency in urbanized area, and white collar had a tendency to consult TCM service. The most commonly adopted TCM treatment is CHM. We also identified the ten most common prescribed Chinese herbal formulas and single herbs for the treatment of psoriasis. Wen-qing-yin and Bai-xian-pi were the most commonly used TCM herbal formula and single herb, respectively. Overall, our study provided valuable information and added value to the existing knowledge regarding TCM treatment for patients with psoriasis.

In our study, women, compared with men, were more likely to use TCM. We found that the highest TCM utilization rate was young people. Several surveys also showed similar findings [14, 32]; women and younger people had a higher usage of TCM. There was also a tendency for TCM users to reside in higher urbanized area. This may be because highly urbanized areas have a high density of TCM doctors in Taiwan [32].

Patients with psoriasis utilized healthcare services significantly more often than those without psoriasis [33], and we found that half of patients with psoriasis used TCM. In this study, patients visited TCM services on an average of 12.0 months after initial diagnosis of psoriasis. Probably most patients usually used Western medicine as the first choice initially. If patients were unsatisfied with conventional therapy, recurrent symptoms, or high costs of biological agents, they might further seek adjunctive TCM consultation [34, 35].

In accordance with other studies in atopic dermatitis or urticaria [13, 36], CHM is the most common treatment approaches. We found that only very few patients received acupuncture therapy. Regarding the visiting frequency, a majority of the patients used TCM service for more than 6 times, which might be due to the confidence in symptoms relief or effectiveness perceived by users. However, for those who received both treatment modalities, they tended to use TCM services more frequently. It is possible that those patients who chose a combination of CHM and acupuncture or traumatology therapy had complicated situations that required more frequent treatment.

Psoriasis is not a disease merely affecting skin. We found that patients with psoriasis were associated with a high degree of incidence rate ratio for visiting TCM clinics when they suffered from various medical comorbidities. Previous investigations were consistent with our findings that psoriasis patients had a broad spectrum of disease category in their clinical visits [2, 37].

According to the theory of traditional medicine, psoriasis is further identified by different patterns, such as blood heat, heat toxin, damp heat, blood stasis, and blood dryness. Our network analysis in Figure 2 included the top 50 combinations of herbal formulas and herbs for psoriasis patients. According to the theory of TCM theory, this core pattern can clear heat, cool the blood, nourish the blood, dispel wind, and dry dampness.

Wen-qing-yin was the most frequently prescribed formula for psoriasis. It was originally documented in an ancient literature as “Wan Bing Hui Chun.” This formula is composed of Si-wu-tang (Four Agents Decoction) and Huang-lian-jie-du-tang (Coptis Toxin-Resolving Decoction). Together in this formula, they can clear heat, transform dampness, and nourish the blood based on the TCM theory. In a previous report, Wen-qing-yin could inhibit the induction phase of various kinds of delayed type hypersensitivity and local graft-versus-host reactions [38]. The second commonly prescribed herbal formula is Xiao-feng-san (Wind-Dispersing Powder). It has long been used to treat skin problems in clinical practice such as atopic dermatitis [13] or urticaria [36]. In a clinical trial conducted in our institution, Xiao-feng-san was found to improve refractory atopic dermatitis symptom and with no side effects [39]. In basic studies, Xiao-feng-san as an antiallergic drug was reported to inhibit IgE dependent histamine release from the cultured mast cells [40]. Xiao-feng-san might also correct the Th1/Th2 balance by preventing the increase in interleukin-4 mRNA expression and the decrease in interferon-gamma mRNA expression to inhibit dermatitis [41]. Long-dan-xie-gen-tang (Gentian Liver-Draining Decoction) is the third most common formula. In clinical practice, Long-dan-xie-gen-tang is commonly prescribed to subjects with chronic hepatitis [42], atopic dermatitis [13], and insomnia [43] in Taiwan. In TCM viewpoint, it can drain fire and clear damp heat. Besides the symptoms of skin, patients with psoriasis often suffered from sleep problems [2, 44]. Whether Long-dan-xie-gen-tang has direct effect on skin or indirect efficacy on comorbidity, such as insomnia, deserves further investigation.

Bai-xian-pi (Cortex Dictamni; Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz.) was the most commonly prescribed single herb. It can clear heat and dry dampness, dispel wind, and resolve toxin. Among the prescribed single herbs, seven of top ten single herbs belonged to the category of “clearing heat.” Tropical treatment of methanol extract of Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz. root bark on dermatitis mice could effectively inhibit skin thickness, hyperplasia, and edema [45]. The anti-inflammatory effects of Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz. may reduce the level of β-hexosaminidase and histamine release [46]. Mu-dan-pi (Cortex Moutan; Paeonia suffruticosa Andrews) was used to clear heat and cool the blood in TCM. Previous study found that the water extract of Moutan Cortex not only inhibited β-hexosaminidase and tumor necrosis factor-α release in IgE-mediated DNP-BSA-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells but also improved the compound 48/80-induced allergic reactions in a mouse model [47]. Zi-cao (Radix Lithospermi; Lithospermum erythrorhizon Siebold & Zucc.; Arnebia euchroma (Royle) I.M.Johnst.; Arnebia guttata Bunge) has been used to clear blood heat and has shown an anti-inflammatory effect in experimental studies [48]. Its ingredient, shikonin, was found to suppress IL-17 signaling in keratinocytes [49]. Di-fu-zi (Fructus Kochiae; Kochia scoparia (L.) Schrad.) has been used to clear heat and dry dampness. It was reported to ameliorate dermatitis via inhibition of the production of proinflammatory cytokines [50]. Sheng-di-huang (Radix Rehmanniae; Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC.) polysaccharides extract was found to increase skin glutathione, superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase activities and decrease skin malondialdehyde level in ultraviolet B ray treated mice, suggesting that it may be useful for skin diseases [51].

Taken together with the classification and principles of TCM formulas and single herbs, our findings corresponded with the viewpoint of TCM, which believes that the occurrence of psoriasis symptoms is related to the blood heat, blood stasis, and blood dryness. However, it has to be pointed out that future validation on their efficacy and safety is necessary.

The strength of this study at least included the following aspects: First, all residents of Taiwan can access the NHI system with low cost and convenience, and thus the accessibility of healthcare, either Western or Chinese medicine, is high. Second, all patients with psoriasis were included in this study and this nationwide population-based study comprehensively included all the prescriptions for psoriasis patients. These TCM formulas and single herbs may provide some thought in the exploration of better treatment options.

Some caveats in this study merit comments. First, this study did not include topical Chinese herbal ointments or herbal bath, which were not the forms of TCM reimbursed by the NHI program. The NHI program only covers TCM prescriptions manufactured by GMP-certified pharmaceutical companies in Taiwan. Future study to explore the topical herbal products is necessary. Second, the severity of psoriasis and efficacy of CHM were not available in this database. Judging from the fact that 70.4% of the patients with psoriasis used TCM service, it is necessary to conduct clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of these prescriptions.

5. Conclusion

This study is the first large-scale survey to analyze TCM utilization patterns among patients with psoriasis in Taiwan. Patients with psoriasis often sought help from TCM treatment. Wen-qing-yin was the most frequently prescribed Chinese herbal formula, while Bai-xian-pi was the most common single herb. Future clinical trials and pharmacological investigations could be developed based on the findings of this study.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by China Medical University under the Aim for Top University Plan of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan. This study was also supported in part by the Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (MOHW105-TDU-B-212-133019). This study was based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database, provided by the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, and managed by National Health Research Institutes.

Disclosure

The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, or National Health Research Institutes.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contributions

Shu-Wen Weng, Jaung-Geng Lin, and Hung-Rong Yen conceptualized the study. Yu-Chiao Wang performed the statistical analysis. Bor-Chyuan Chen, Chun-Kai Liu, Mao-Feng Sun, Jaung-Geng Lin, and Hung-Rong Yen contributed to the interpretation of TCM data. Bor-Chyuan Chen interpreted the pharmacological mechanisms. Ching-Mao Chang conducted the network analysis of the core prescription pattern. Shu-Wen Weng, Bor-Chyuan Chen, and Hung-Rong Yen drafted the manuscript. Jaung-Geng Lin and Hung-Rong Yen finalized the manuscript. Shu-Wen Weng and Bor-Chyuan Chen have equal contribution.

References

- 1.Parisi R., Symmons D. P., Griffiths C. E., Ashcroft D. M., Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) Project Team Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2013;133:377–385. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai T.-F., Wang T.-S., Hung S.-T., et al. Epidemiology and comorbidities of psoriasis patients in a national database in Taiwan. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2011;63(1):40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanderpuye-Orgle J., Zhao Y., Lu J., et al. Evaluating the economic burden of psoriasis in the United States. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2015;72(6):961.e5–967.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen K.-C., Hung S.-T., Yang C.-W. W., Tsai T.-F., Tang C.-H. The economic burden of psoriatic diseases in Taiwan. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2014;75(3):183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boehncke W.-H., Schön M. P. Psoriasis. The Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes L., Kaya G., Rollason V. Topical corticosteroid-induced skin atrophy: a comprehensive review. Drug Safety. 2015;38(5):493–509. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlager J. G., Rosumeck S., Werner R. N., et al. Topical treatments for scalp psoriasis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009687.pub2.CD009687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papp K., Cather J. C., Rosoph L., et al. Efficacy of apremilast in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2012;380(9843):738–746. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Archier E., Devaux S., Castela E., et al. Carcinogenic risks of Psoralen UV-A therapy and Narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2012;26(3):22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conway R., Low C., Coughlan R. J., O'Donnell M. J., Carey J. J. Risk of liver injury among methotrexate users: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2015;45(2):156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maza A., Montaudié H., Sbidian E., et al. Oral cyclosporin in psoriasis: a systematic review on treatment modalities, risk of kidney toxicity and evidence for use in non-plaque psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2011;25(supplement 2):19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.03992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Cranenburgh O. D., de Korte J., Sprangers M. A. G., de Rie M. A., Smets E. M. A. Satisfaction with treatment among patients with psoriasis: a web-based survey study. The British Journal of Dermatology. 2013;169(2):398–405. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin J.-F., Liu P.-H., Huang T.-P., et al. Characteristics and prescription patterns of traditional chinese medicine in atopic dermatitis patients: ten-year experiences at a medical center in taiwan. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2014;22(1):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang C.-Y., Lai W.-Y., Sun M.-F., et al. Prescription patterns of traditional Chinese medicine for peptic ulcer disease in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;176:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang M.-C., Pai F.-T., Lin C.-C., et al. Characteristics of traditional Chinese medicine use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;176:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee A. L., Chen B. C., Mou C. H., Sun M. F., Yen H. R. Association of traditional Chinese medicine therapy and the risk of vascular complications in patients with type II diabetes mellitus: a nationwide, retrospective, Taiwanese-registry, cohort study. Medicine. 2016;95(3) doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000002536.e2536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lien A. S.-Y., Jiang Y.-D., Mou C.-H., Sun M.-F., Gau B.-S., Yen H.-R. Integrative traditional Chinese medicine therapy reduces the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2016;191:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yen H.-R., Chen Y.-Y., Huang T.-P., et al. Prescription patterns of Chinese herbal products for patients with uterine fibroid in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;171:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleischer T., Chang T.-T., Chiang J.-H., Chang C.-M., Hsieh C.-Y., Yen H.-R. Adjunctive Chinese Herbal Medicine therapy improves survival of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Cancer Medicine. 2016;5(4):640–648. doi: 10.1002/cam4.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen H. R., Lai W. Y., Muo C. H., Sun M. F. Characteristics of traditional Chinese medicine use in pediatric cancer patients: a nationwide, retrospective, Taiwanese-registry, population-based study. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1534735416659357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang C. S., Yang L., Zhang A. L., et al. Is oral Chinese herbal medicine beneficial for psoriasis vulgaris? A meta-analysis of comparisons with acitretin. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2016;22(3):174–188. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu J. J., Zhang C. S., Zhang A. L., May B., Xue C. C., Lu C. Add-on effect of Chinese herbal medicine bath to phototherapy for psoriasis vulgaris: a systematic review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:14. doi: 10.1155/2013/673078.673078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin Y.-K., See L.-C., Huang Y.-H., et al. Efficacy and safety of Indigo naturalis extract in oil (Lindioil) in treating nail psoriasis: a randomized, observer-blind, vehicle-controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2014;21(7):1015–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan Y., Liu W., Andres P., et al. Exploratory clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of a topical traditional Chinese herbal medicine in psoriasis vulgaris. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015:6. doi: 10.1155/2015/719641.719641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landis E. T., Davis S. A., Feldman S. R., Taylor S. Complementary and alternative medicine use in dermatology in the United States. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2014;20(5):392–398. doi: 10.1089/acm.2013.0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.NHIA. National Health Insurance Annual Report 2015-2016. Taipei, Taiwan: National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang C. C., Lee Y. C., Lin C. C., et al. Characteristics of traditional chinese medicine usage in patients with stroke in taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2016;186:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bensky D., Clavey S., Stoger E. Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica. 3rd. Seattle, Wash, USA: Eastland Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheid V., Bensky D., Ellis A., Barolet R. Chinese Herbal Medicine: Formulas & Strategies. Eastland Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan K., Shaw D., Simmonds M. S. J., et al. Good practice in reviewing and publishing studies on herbal medicine, with special emphasis on traditional Chinese medicine and Chinese materia medica. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;140(3):469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang C. M., Chu H. T., Wei Y. H., et al. The core pattern analysis on Chinese herbal medicine for Sjogren's syndrome: a nationwide population-based study. Scientific Reports. 2015;5, article 9541 doi: 10.1038/srep09541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shih C.-C., Liao C.-C., Su Y.-C., Tsai C.-C., Lin J.-G. Gender differences in traditional chinese medicine use among adults in Taiwan. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032540.e32540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kao L.-T., Wang K.-H., Lin H.-C., Li H.-C., Yang S., Chung S.-D. Use of health care services by patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. The British Journal of Dermatology. 2015;172(5):1346–1352. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ben-Arye E., Ziv M., Frenkel M., Lavi I., Rosenman D. Complementary medicine and psoriasis: linking the patient's outlook with evidence-based medicine. Dermatology. 2003;207(3):302–307. doi: 10.1159/000073094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim G.-W., Park J.-M., Chin H.-W., et al. Comparative analysis of the use of complementary and alternative medicine by Korean patients with androgenetic alopecia, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2013;27(7):827–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chien P.-S., Tseng Y.-F., Hsu Y.-C., Lai Y.-K., Weng S.-F. Frequency and pattern of Chinese herbal medicine prescriptions for urticaria in Taiwan during 2009: analysis of the national health insurance database. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;13, article 209 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeung H., Takeshita J., Mehta N. N., et al. Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: a population-based study. JAMA Dermatology. 2013;149(10):1173–1179. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mori H., Fuchigami M., Inoue N., Nagai H., Koda A., Nishioka I. Principle of the bark of Phellodendron amurense to suppress the cellular immune response. Planta Medica. 1994;60(5):445–449. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng H.-M., Chiang L.-C., Jan Y.-M., Chen G.-W., Li T.-C. The efficacy and safety of a Chinese herbal product (Xiao-Feng-San) for the treatment of refractory atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2011;155(2):141–148. doi: 10.1159/000318861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shichijo K., Saito H. Effect of Chinese herbal medicines and disodium cromoglycate on IgE-dependent histamine release from mouse cultured mast cells. International Journal of Immunopharmacology. 1998;19(11-12):677–682. doi: 10.1016/s0192-0561(97)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao X. K., Fuseda K., Shibata T., Tanaka H., Inagaki N., Nagai H. Kampo medicines for mite antigen-induced allergic dermatitis in NC/Nga mice. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2005;2(2):191–199. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen F.-P., Kung Y.-Y., Chen Y.-C., et al. Frequency and pattern of Chinese herbal medicine prescriptions for chronic hepatitis in Taiwan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;117(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen F.-P., Jong M.-S., Chen Y.-C., et al. Prescriptions of Chinese herbal medicines for insomnia in Taiwan during 2002. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011:9. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep018.236341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta M. A., Simpson F. C., Gupta A. K. Psoriasis and sleep disorders: a systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2016;29:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim H., Kim M., Kim H., San Lee G., An W. G., Cho S. I. Anti-inflammatory activities of Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz., root bark on allergic contact dermatitis induced by dinitrofluorobenzene in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;149(2):471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han H.-Y., Ryu M. H., Lee G., et al. Effects of Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz., root bark on ICAM-1 expression and chemokine productions in vivo and vitro study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;159:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kee J.-Y., Inujima A., Andoh T., et al. Inhibitory effect of Moutan Cortex aqueous fraction on mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation. Journal of Natural Medicines. 2015;69(2):209–217. doi: 10.1007/s11418-014-0880-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang C. S., Yu J. J., Parker S., et al. Oral Chinese herbal medicine combined with pharmacotherapy for psoriasis vulgaris: a systematic review. International Journal of Dermatology. 2014;53(11):1305–1318. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu Y., Xu X., Gao X., Chen H., Geng L. Shikonin suppresses IL-17-induced VEGF expression via blockage of JAK2/STAT3 pathway. International Immunopharmacology. 2014;19(2):327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi Y. Y., Kim M. H., Lee J. Y., Hong J., Kim S.-H., Yang W. M. Topical application of Kochia scoparia inhibits the development of contact dermatitis in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;154(2):380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sui Z., Li L., Liu B., et al. Optimum conditions for Radix Rehmanniae polysaccharides by RSM and its antioxidant and immunity activity in UVB mice. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2013;92(1):283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]